CHAPTER 4Conditions

It would be unusual to find either decolonization or feminization described as conditions for anarchy even though these demands are now frequently heard: a condition seems too rigid, threatening to fix relationships in ways that most anarchists would consider un-anarchist. However, the term can be used more loosely: lots of anarchists have set certain minimal tests for their own interactions. Manifestos and safer spaces policies are examples of the sorts of conditions anarchists propose. And some anarchists have devised complex regulatory rules for proposed alternatives.

In this chapter I explore anarchist constitutions, showing how anarchists who sorted themselves into individualist and communist camps envisaged the functioning of anarchist societies. This leads us to a consideration of anarchist utopias as well as of anarchist conceptions of democracy.

Anarchist constitutions

In 1909 Max Nettlau, often considered the first great historian of anarchism, discovered an article written in 1860 by the botanist and economist P. E. de Puydt entitled ‘Panarchie’. It described the convention that everybody submit to one form of government as fundamentally illiberal. By ‘government’, de Puydt did not mean the parties or factions that competed for control of institutional power but the foundational principles of governance. Whether government was ‘constituted upon a majority decision or otherwise’, he believed that existing restrictions on choice were prescriptive. Short of emigrating, dissenters had no means of expressing their dissatisfaction with the systems of government preferred by the majority. But the majority, too, were denied real choice once a social order had been established, though they might consent (tacitly or explicitly) on the basis of the advantages they derived from it.

De Puydt, Nettlau explained, had been a free-market liberal, a supporter of laissez-faire economics, and he had attempted to extend the same principles of liberty he saw in the market to the political realm. The freedom de Puydt wanted was ‘the freedom to be free or not free, according to one’s choice’. His proposal was ‘panarchist’. He wanted to give each person the right to ‘select the political society in which they want to live’.

How would panarchy work? The de-territorialization of government was the central principle. Government, or social organization (the term Nettlau preferred), would be based on subscription not prescription. The model was the ‘civil registry office’:

In each municipality a new office would be opened for the Political Membership of individuals with governments. The adults would let themselves be entered, according to their discretion, in the lists of the monarchy, or the republic, etc.

From then on they remain untouched by the governmental systems of others. Each system organizes itself, has its own representatives, laws, judges, taxes, regardless of whether there are two or ten such organizations next to each other.

For the differences that might arise between these organizations, arbitration courts will suffice, as between befriended peoples.1

Surprisingly, de Puydt was willing to include anarchy in his choice-set. In fact, he was as critical of Proudhon’s federalist proposals as he was of the various statist options proffered by republicans, liberals and monarchists. From his perspective, anarchists crossed a pluralist panarchist line when they recommended a limited set of political models. For him, anarchy was an option as restricted as monarchy or republicanism. In contrast to anarchists, panarchists offered a full range of governance models, marketing them to meet the claimed demands of political consumers.

From an anarchist perspective, de Puydt mistakenly conflated government with state. He either misunderstood or wrongly rejected the anarchist idea that there was a fundamental difference between statism and anarchy. De Puydt placed anarchy and statist forms of government on a single spectrum whereas anarchist taxonomies of government – monarchist, republican, liberal – assumed this basic division. Admittedly, this also meant that anarchists were offered fewer choices than de Puydt proposed. They were clearly unable to sanction forms of governance that facilitated and legitimized uneven distributions of power, exploitation and domination. Yet beyond this basic point there was no agreed view about the constitution of anarchy. Anarchists disagreed about the sort of power that should be constrained and how best to institutionalize those constraints to safeguard anarchist principles.

Some anarchists argued that it was impossible to devise a constitutional framework for anarchy. Émile Armand, a free-love, antimilitarist propagandist, was one. Describing life as an experiment, he argued that anarchists should seek to live it ‘constantly … outside of the “law” or “morality” or “customs”’. Life as experiment ‘cuts programs to shreds, tramples over properties, smashes the windows, descends from the ivory tower. Vagabond, it deserts the city of the Acknowledged Fact, leaving through the gate of Final judgment, seeking adventure in the countryside, open to the unexpected.’2 The only rule this seemed to allow was the end of all rules. In fact, Armand’s politics was more complicated: he combined his exhilarating notion of experiment with a conception of self-organization and he expected that experimenters would spontaneously arrange their collective affairs:

The individualist knows that relations and agreements among men will be arrived at voluntarily; understandings and contracts will be for a specified purpose and time, and not obligatory; they will always be subject to termination; there will not be a clause or an article of an agreement or contract that will not be weighted and discussed before being agreed to; a unilateral contract, obliging someone to fill an engagement he has not personally and knowingly accepted, will be impossible. The individualist knows that no economic, political or religious majority – no social group whatever – will be able to compel a minority, or one single man, to conform against his will to its decisions or decrees.3

Armand’s response speaks to a deep and long-held anti-constitutional bias in anarchist thinking. Yet his rejection of the plans that other anarchists formulated was based on a refusal to recognize the constitutional status of the rules he hardwired into experimenters’ brains. Although anarchists have been largely reluctant to use the language of constitutionalism to explore their proposals, those less squeamish about rule-making have argued that greater specification of anarchist social relations, perhaps even extending beyond men, is both necessary and desirable.

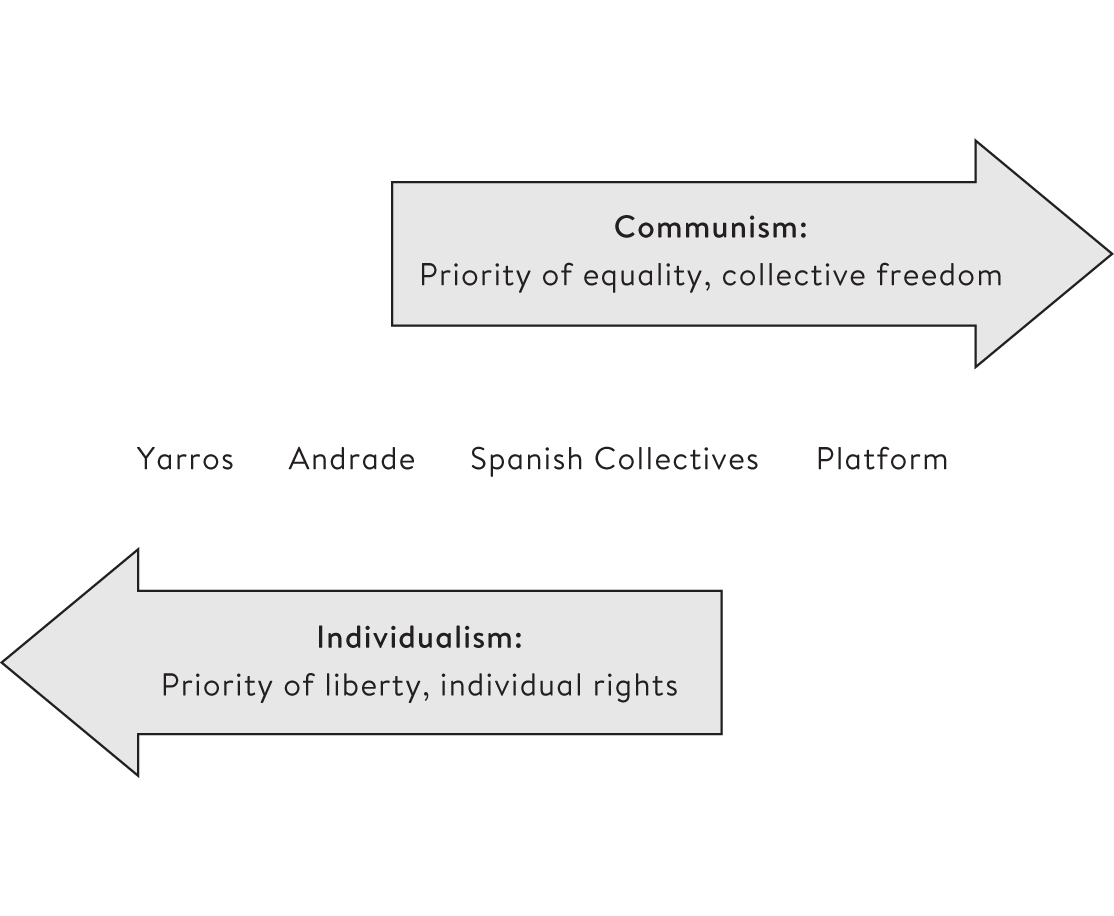

In the face of the question ‘Which forms of social organization are best suited to realize anarchist principles?’ anarchists developed two broad constitutional models. As we will see, the constitutions such as those designed by David Andrade and Victor Yarros were individualist while those coming from Platformists and Spanish anarchists were communist.

Individualist constitutional experiments

AN ANARCHIST PLAN OF CAMPAIGN

David Andrade was a prominent member of the Melbourne Anarchist Club active from the 1880s. He learnt about Bakunin’s and Proudhon’s ideas reading Benjamin Tucker’s paper Liberty and Moses Harman’s paper Lucifer the Lightbearer. These were among the most celebrated individualist-anarchist papers in America; Lucifer’s profile was raised after the censorious Comstock Laws were used to prosecute Harman for daring to discuss marital sex and rape within marriage. Andrade shared Tucker’s view on law and government, though his view on capital and profit was less relaxed. Like Tucker, he described himself as an individualist and socialist. For Andrade, individualist anarchism was not at odds with socialism. It was just a non-communist version of it.4

In 1888 Andrade published his constitution: An Anarchist Plan of Campaign.5 It was designed to foster the spread of anarchist social principles in Australia and beyond by appealing to the workers of the world. His idea was that workers would establish co-operatives to purchase goods in bulk and run anarchist economies selling to the public within the capitalist state system. Co-operatives would generate their own capital, purchase their own land, set up their own factories and stores and construct their own living spaces. The expansion of the movement over time would depend both on the economic success of the ventures and the robustness of their political arrangements.

Andrade’s chief concern was to secure economic equality or, as he put it in his dedication, to ‘better our sad condition’ by pointing to ‘a method of escape from … intolerable slavery’. Insofar as the constitution was designed to curtail power, Andrade most wanted to curb the power to accumulate individual profit through the exploitation of labour: ‘Profit-making is the first form of exploitation that the labourer must understand.’ This constitution, then, was an agreement between workers to organize themselves as equal co-operators. Yet it also had a positive, empowering aspect. The Plan would ensure that ‘laborers are no longer expropriated slaves, competing on a capitalistic labor market for employment; but free men, possessing their own property and capital, and employing themselves.’

With thirteen articles, Andrade’s model constitution was short and simple. There was no preamble and no grandiose sentiments. The wording was similarly plain and clear. The egalitarian norms of the constitution were embedded in institutional provisions and regulatory rules. It was also meant to deal with two problems which Andrade anticipated. One was the necessity of complying with ‘statute law’ and being ‘amenable to, and tied down by the regulations and restrictions of, the very laws and legal institutions which we are striving to abolish’. The other was to protect the co-operative from ‘intriguing schemers’ and internal collapse.

Andrade proposed a number of measures to guard against this possibility. The constitution guaranteed all members access to collectively owned property ‘free of all change, no rent being demanded of its use’. Each member would be an equal shareholder in the co-operative, insofar as the law allowed, and would be ‘equally remunerated, on a time basis, for any services performed’. Labour notes would be issued to run the economy independently of the state and guard against individual capital accumulation. The commitment to equality was also written into the constitution: ‘To guard against any possible violation of this principle, it should be a fixed understanding, introduced into the constitution of the cooperation at its inception’ that the constitution was ‘only alterable by the unanimous consent of the members’. Profiteers who entered the co-operative in order to exploit it would have to secure the support of all members to change the rules of co-operation. The Plan gave members the right to withdraw from the co-operative at any time but otherwise obliged them to adhere to its terms. Anyone who violated the agreement could be expelled without the possibility of readmission by majority vote.

Most of the rules Andrade proposed were written into the Plan. His general view that ‘[f]ree men require no rulers’ meant that non-constitutional rules could be kept to a minimum: individuals could determine for themselves how they wanted to live within the framework of the co-operative. At the same time, it was important to introduce rules to regulate the institutions the co-operatives would have to run. Andrade imagined the establishment of a Mutual Bank which would free the co-operative from reliance on ‘privileged bankers’ and support loans for expansion, particularly house-building. He also recommended that the co-operative produce its own ‘journal and general literature’ to ‘educate the public concerning the principles and methods adopted’ by the co-operative and counteract the lies likely to be spread in the capitalist press. The smooth management of these institutions would require other sets of rules. Co-operation required co-ordination and administration. The Plan included rules about the appointment of managers and the conduct of business meetings. In addition, Andrade empowered managers to introduce by-laws to oversee the day-to-day running of the co-operative (time-keeping, accountancy and distribution of goods produced by the members through warehouses), as long as these did not contravene the constitution.

Andrade’s hope was that the economic independence achieved by co-operation would foster a spirit of political independence. For example, the constitution guaranteed that there was to be ‘no recognized inequality or other distinction, on account of sex’. Andrade added that the habit of co-operation would breed new norms, enriching and improving the quality of interpersonal relations. Thus the constitutional Plan of Campaign would prompt a cultural change. Having become ‘the equal of man’ woman’s ‘wretched dependence upon him will have vanished, and she will be sovereign over her own body, her own mind, and her own passions, instead of being the property of a husband and subject to all the right or wrongs he may inflict upon her’. Once released from ‘matrimonial bondage’ women would become happier and healthier, breeding happier, healthier children, too. ‘The nation will become healthier, happier, and freer; and the miserable, puny, vicious, licentious generation of the present will make way for a higher and nobler humanity than the world has yet seen’. For good measure, Andrade argued that crime would become a thing of the past as the realm of freedom expanded. The ‘toiling millions who … have groaned in misery under the yoke of law, authority, plunder, and crime, will feel a new life within them as they step out into the full light of liberty’. Clearly, Andrade was an optimist, yet his hopes were not limitless: the criminality that co-operation eradicated was only the idlers’ advantage of reaping a reward from others’ toil. And the anarchist freedom he described was grounded in the respect for anarchist rules and the sanctity of the constitution.

CONSTITUTION OF THE BOSTON ANARCHISTS’ CLUB

Victor Yarros unusually began his chequered political career as a communist before embracing individualism under the influence of Benjamin Tucker. Born in Kiev in 1865, he arrived in America in the 1880s already a seasoned activist. He became a leading contributor to Tucker’s Liberty and ended life as a social democrat, convinced that the state had an important role to play in bringing about equality.6 Nonetheless, in 1887, six years after Tucker started Liberty, Yarros delivered an address at the first meeting of the Boston Anarchists’ Club. This was later published as Anarchism: Its Aims and Methods. It included a formal constitution which was adopted by the Club.

The ‘abolition of all government imposed upon man by man’ was the central theme of Yarros’s extended preamble and the major substantive principle of what followed. Subscribing to Proudhon’s view that ‘liberty is the mother, not the daughter of order’ he proclaimed government ‘is the father of all social evil’. Quoting copiously from the first issue of Liberty, he argued that the anarchists’ ‘chief battle’ was with the state ‘that debases man’, that ‘prostitutes woman … corrupts children … trammels love … stifles thought … monopolizes land … limits credit … restricts exchange’ and ‘gives idle capital the power of increase and allows it, through interest, rent, and profits, to rob industrious labour of its products’. The abolition of government was also enshrined in the second article of the constitution. Indeed for Yarros, it was ‘the definition of the term An-archy’; it was the ‘central affirmation underlying our philosophy and system of thought’. Casting about for a positive term to describe it, Yarros chose ‘Individual Sovereignty, or Egoism’. In contemporary language it was libertarian anti-capitalist.7

Like Andrade, Yarros listed thirteen articles. With the exception of the second, all referred to the internal organization of the Club and the conduct of its business meetings. Any signatory to the constitution could become a member. All members had equal voting rights. There was no membership fee; members made monthly contributions to the Club’s expenses as ‘circumstances will allow’. Members elected a Chair at each monthly meeting by majority vote. The only ‘regular official’ was the Secretary-Treasurer. This was also an elected position which could be held for as long as a year. The Chair had significant powers. Article V gave the Chair power to ‘preside … at all meetings of the Club, public or private’ that may be held between regular monthly meetings. Article IX specified that the ‘conduct of each meeting shall be vested solely in the chairman, and from his decisions there shall be no appeal’. Sensitive to potential abuse, Yarros ensured that there were checks on these powers. Ten members of the Club could request the Secretary-Treasurer to call special business meetings and article X provided that the Chair could be removed by a 75 per cent majority vote. Yarros also limited the powers of the Secretary-Treasurer, but the checks here were weaker: not only were the ‘duties … incumbent upon such an official’ left unspecified, but the membership could remove and replace the incumbent only on condition that ‘each member of the Club has been notified by the Secretary-Treasurer that such a proposition is to come before the meeting’. Members could leave the Club at any time but had to resign formally by notifying the Secretary-Treasurer in writing. All decisions on ordinary business, as well as the removal of the Secretary-Treasurer, were made by simple majority vote. Dissenters had the right to have their views recorded on request. Exceptionally, changes to the constitution had to be agreed unanimously. Proposals for constitutional change could only be debated at regular business meetings and although they could be tabled at special meetings, Club members had to be notified by the Secretary-Treasurer in writing prior to any vote. No amendment could be ‘offered twice within a period of three months’.8

Yarros included two extensive notes to explain the powers of the Chair and the use of majority voting. While he argued that the difference between the anarchist and government principle was ‘too plain and striking not to be perceived and admitted’, their inclusion indicated that he recognized the possibility of there being some confusion between the anti-government position he outlined in the preamble and the constitutional provisions he made.

The difficulty was resolved by recourse to Yarros’s conception of voluntaryism. Here he looked to another prominent individualist, the abolitionist Stephen Pearl Andrews, who had used the example of the parlour to model the best kind of social interaction. In the beautiful laissez-faire parlour the ‘[i]ndividuality of each is fully admitted. Intercourse is … perfectly free. Conversation is continuous, brilliant, and varied. Groups are formed according to attraction … continually broken up, and re-formed through the operation of the same subtle and all-pervading influence’. It was a place of liberty and equality. Any ‘laws of etiquette … are mere suggestions of principles admitted into and judged of’ by each person. Andrews contrasted this to the ‘legislated gathering’. Here, the time each had to speak was ‘fixed by law’. The positions of the participants were ‘precisely regulated’. And their topics of conversation ‘and the tone of voice and accompanying gestures carefully defined’.9 The legislated parlour was intolerable slavery.

Yarros applied Andrews’s analogy to the relationship of anarchy to the state. The state was a special kind of legislated organization, a ‘war-institution’ that was built on aggression and a class institution that produced inequalities by granting privileges and creating distinctions. Government ‘set men against men and classes against classes by their favouritism … and special opportunities’. Once established, it used force to compel obedience to these arrangements. But anarchists refused to consent to the government’s abuses.

Like de Puydt’s panarchists, Yarros argued that anarchists had no intention of forcing governmentalists to relinquish their preferred order in favour of anarchy. But in contrast to the panarchists, he characterized government as monopoly and argued that the state was crushing alternative forms of governance. Since the state was tyranny, he also argued that anarchists had the right to use any means necessary to resist it. While he believed that propaganda by the word was more effective than impulsive revolutionary action, he also held that in war all was fair. Indeed, in a nod to John Most, one of the most celebrated communist advocates of propagandistic action, he urged anarchists to gen up on the science of revolutionary warfare to ensure their own security.

Yarros was unimpressed with the argument that majority rule was the same as government by consent. Democracy might be the ‘least objectionable form of rule’, but he refused to accept that individual consent could ever legitimately be set aside on the basis of a majority decision. If A and B had no ‘rightful authority’ over C when acting separately and independently, how was it possible that C’s preferences could be overridden when they acted conjointly? Either A, B and C had ‘natural rights to life and liberty’, or they did not.10

Two important points emerged from Yarros’s discussion. First, the anarchy of the parlour was not an unregulated order but one that promoted ‘another kind of regulation’. Second, the rules that anarchists adopted to self-regulate their societies were entirely voluntary. Admitting that government was vastly more complicated and considerably larger than a parlour, Yarros contended that ‘the question of the scope and proportions of government power is a subordinate and purely practical question’. The difference between government and anarchy was one of principle: only the latter ensured that ‘members have the right to withdraw at any time’ and that ‘no limit be put beforehand to the limit of its operations’. Members can ‘increase and diminish its functions at will, and experience may safely be relied upon for demonstrating just what the amount of benefit there is to be derived from associative effort’.11

Having once decided to combine voluntarily, Yarros argued, anarchists were free to adopt majority decision-making to conduct their business. He included the provision in the constitution for reasons of efficiency. Nobody could possibly ‘confound this with the system of majority rule obtaining under democratic forms of government’, for there was nothing voluntary about the submission that government decisions involved. Similarly, if anarchists decided to invest one or some of their number with greater decision-making powers than the rest, this was because they reserved the right to ‘choose any mode of practical organization’ to carry out their wishes. They could abandon or modify these working arrangements at any time. Thus the Chair of the Club did not function as an authority, even though it was possible for the Chair to exercise discretion in ‘extraordinary cases’. Members could not be coerced to accept the Chair’s rulings for an anarchist principle was that the Chair followed the members’ instructions.

Like Andrade, Yarros expected that anarchist orders would be more stable and peaceful than government, simply because anarchists would be free to conduct their business without coercion. His aim was to carve out anarchist spaces for anarchists and his constitution was intended as a model for others to adopt. Like Andrade, he believed that the success of anarchy depended on building relationships between small, resilient clubs and societies. Yet unlike Andrade, Yarros did not anticipate the extension of the model to the workers of the world, even though this was conceivable. Indeed, his elitism helped explain his confidence in his constitutional scheme. As he put it, he was not interested in rescuing ‘half-starved’ ‘blind slaves’ who worshipped the ‘power which grinds them to powder’ and stood ready ‘to defend it with their last drop of blood’.12 The anarchist constitution protected the rights and liberties of the enlightened and intelligent few, able to resolve their differences over a glass of wine. Everyone else was free to put up with the evils of the legislated order.

Communist constitutions

THE ORGANIZATION OF THE PLATFORM

Following the Bolshevik defeat of the anarchist campaign in the Ukraine, the insurgent leader Nestor Makhno and some of his group went into exile in Paris. They set up a paper, Dyelo Truda, and in 1926 published the Draft Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists. This stirred a lot of controversy in the anarchist-communist movement and some leading organizationalists, including Malatesta, were quite critical of it. Its leading idea was that anarchism lacked a ‘homogeneous program’ and a ‘general tactical and political line’.13 For the Dyelo Truda group, this lack helped explain the success of Bolshevism and the marginalization of anarchism in Russia, in both urban and rural areas. But critics found the proposed remedy too strict and protested that it imposed a party line. The Platformists – the name that Maknno’s supporters now took – responded that anarchists would never be able to disseminate their message to the oppressed for as long as their ideas remained unclear and undefined.

The Platform was anarchist but called itself libertarian communist. The change in language reflected its founders’ desire to distance themselves equally from the Bolsheviks, who also called themselves communist, and individualist anarchism. Platformists embraced the ‘principle of individuality in anarchism’ but rejected the individualists’ distortion of this principle to mean egoism, which showed a ‘cavalier attitude, negligence and utter absence of all accountability’.14 Libertarian communists by contrast held that ‘social enslavement and exploitation of the toiling masses form the basis upon which society stands’. They saw violent social revolution as the ‘only route to the transformation of capitalist society’. And they recognized that ‘free individuality’ develops ‘in harmony’ with ‘social solidarity’. The egalitarianism of the libertarian communist model rested on the equal moral worth and rights of each individual. The realization of this right demanded the abolition of exploitation and this was to be achieved through socialization of property and the means of production and the ‘construction of economic agencies on the basis of equality and self-governance of the laboring classes’.15 The Platform was formally committed to the communist principle of distribution according to need and distinguished itself from authoritarian communism by also specifying a commitment to workers’ ‘liberty and independence’. This was an ‘underlying principle’ of the ‘new society’.16

To overcome the authoritarianism of the state a federal system was proposed. That involved the establishment of special, dedicated libertarian communist organizations and the organization of free workers’ and peasants’ co-operatives. The former had an educative function, disseminating libertarian communist ideas. The latter were the foundational units of libertarian communist organization. They would be organized locally, uniting from the bottom up, to construct larger units:

There will be no bosses, neither entrepreneur, proprietor nor proprietor state (as one finds today in the Bolsheviks’ State). In the new production, organizing roles will devolve upon specially created administrative agencies, purpose-built by the laboring masses: workers’ soviets, factory committees or workers’ administrations of firms and factories. These agencies, liaising with one another at the level of the township, district and then nation, will make up the township, district and thereafter overall federal institutions for the management of production.17

Federalism was defined as the ‘free agreement of individuals and organizations upon collective endeavour geared towards a common objective’. It was coupled with ideological and tactical unity and so required self-discipline and the acknowledgement of individuals’ rights and duties. The ‘right to independence, to freedom of opinion, initiative and individual liberty’ was part of it. The other part was the acceptance of ‘specific organizational duties’, the insistence that ‘these be rigorously performed, and that decisions jointly made be put into effect’. This provision was in line with the commitment to collective responsibility or, as Platform put it, the idea that ‘operating off one’s own bat should be decisively condemned and rejected in the ranks of the anarchist movement’.18

The proposals outlined in the Platform assumed that libertarian communists would be organizing in preparation for a revolutionary war or during one. The formation of military units was therefore integral to the Platform. These were to be run on a voluntary basis, but according to strict rules: no conscription, free ‘revolutionary self-discipline’ and political control by the workers’ and peasants’ organizations.19 Expecting to operate in war conditions, the Platform contained all sort of plans to cover contingencies: production failures and shortages resulting from economic dislocation. Perhaps recognizing the tension between the commitment to communism and the principle of liberty, it also took a cautious approach to the collectivization of land. This policy was not to be pursued as systematically as the collectivization of industry. Should land workers who were used to working the land ‘self-reliantly’ object to communist principles, it was better to run a mixed economy rather than impose communism, even if this meant allowing some private cultivation while collectivization spread. There was a degree of vagueness, too, in the administrative proposals the Platform made and about the role of the Executive Committee of the Anarchist General Union, and indeed, how this Union was to function. The authors openly admitted these gaps. For them, the Platform was only a beginning, a groundwork for general organization. It was up to the General Union of Anarchists to ‘expand upon and explore it so as to turn it into a definite program for the whole anarchist movement’.20 It was an ambitious plan and typically anarchist in the way it embraced its own fallibility.

COLLECTIVES IN TERUEL IN THE SPANISH REVOLUTION

In 1936, when General Franco launched his military coup against the Spanish Republican government, anarchists across the country rose in revolution, taking control of significant areas of the territory within the Republican zone. In Aragon, in the north-east of Spain, about three-quarters of the land mass were collectivized. It is estimated that in February 1937, just over six months into the revolution, there were 275 collectives with around 80,000 members. Three months later 175 more were added to this total, together with another 100,000 members. The process of collectivization, often spontaneous and sometimes driven by anarchist militias, can be understood as a constitutional one. The collectives represented ‘an attempt to create a model, an example for the future of what, once the war was won, a new libertarian society would be like’. They were designed to abolish ‘the exploitation of man by man’. Moreover, a federal structure linking ‘each village at the district and regional level’ was introduced. First producing for themselves, the collectives channelled surpluses to the Council of Aragon to ‘sell or exchange it with other regions or abroad’.21

Collectivization varied from place to place. Naturally, there were disagreements about putting it into practice. A scene in Ken Loach’s film Land and Freedom depicts land workers discussing how property should be collectivized and disagreeing about the rewards that should go to individual cultivators. Rather than illustrating anarchist ‘chaos’, it showed how the commitment to ‘anarchy without adjectives’, the idea promoted by Tárrida del Mármol the engineer and survivor of the Monjuich tortures, was supposed to operate on the ground and be promoted.

In Mas de las Matas, a commune in Teruel, the process was reasonably smooth: a specially formed committee proposed the collectivization of the existing small and medium-sized holdings. Smallholders and artisans handed over their land, tools, livestock and wheat to the collective. Labour groups were then organized and assigned to one of the twenty-odd new land sectors and assorted workshops. The principles of the collective were egalitarian. Money was abolished and the communist principle of distribution according to need was adopted for all collectively produced goods. In the absence of money a rationing system was used for distribution.

There was no formal plan. Assemblies, which included women, were held to discuss special matters, but the fundamental point for the collective’s success was the commitment to reconstitute social relations through collectivization. Not everybody subscribed to the new egalitarianism, so in order to ease the tensions that collectivization caused, concessions were made. Small portions of irrigated land were set aside for each collectivist to grow crops for personal use and each was allowed to keep chickens and rabbits. Agreeing these rules, the collective sought to institutionalize new social norms. Taverns were closed (though wine was included in the ration). Gambling was banned. Resources were found to send a villager to Barcelona to undergo a medical treatment that he otherwise would never have afforded. A threshing machine was procured from the surplus the collective produced. Schools were re-opened, staffed by students and stocked with ‘rationalist’ teaching materials from Barcelona. New schools opened to provide education to those formerly excluded from education.

The canton of Alcorisa, about fifteen kilometres to the north-east of Mas de las Matas, was also collectivized. It was a relatively wealthy canton of nineteen villages with a population of 4,000. After driving out the Francoist rebels and Civil Guard, a hastily constituted Defence Committee, made up of republicans and anarchists, decided to take control of production and prohibit private commerce. In parallel, locally syndicated agricultural workers set about organizing a new system of production, as in Mas de las Matas, assigning teams to work twenty-three sections of collectivized land. Machinery was redistributed and land surveys were completed. Unlike Mas de las Matas, Alcorisa was ‘definitively constituted’.22 Two lawyers were instrumental in drawing up the terms of the agreement. Its main articles related to property in goods, usufruct, membership, withdrawal and administration.

Property and assets owned by families and individuals, the Municipal Council and the agricultural syndicate were placed in common ownership, to be held on the basis of use. All members of the syndicate were automatically considered members of the collective. New members were admitted by decision of a General Assembly. This was the main decision-making body of the collective and its role, along with the rights and duties of the collectivists, was also specified in the constitution. Withdrawal from the collective was possible, but the collective then reserved the right not to return goods and property, in order to guard against speculation. A five-member commission was set up to take charge of the administration. One served as secretary and the others had briefs to manage food supplies, agriculture, labour and public education.

The collective subscribed to libertarian socialist values. The abandonment of legal marriage was one indicator. In addition the General Assembly adopted the communist principle of distribution according to need. Vouchers were issued by the Defence Committee and these could be exchanged for goods in the local food stores. Services were free of charge. Money was abolished and Alcorisa introduced a point system instead of providing a standard ration, as was done in Mas de las Matas. This meant that individuals and families could choose what they wanted from the available stocks. The collective ran a cinema from a converted church and transformed a convent into a school. It had four grocers and four butchers, a textile co-operative, a haberdashery and tailor’s shop, various hairdressers and barbers, a joinery and smithy. It set up a salt factory, ran a hotel and stud farm and managed a herd of cows. According to Gaston Leval, the administration ‘was responsible for providing accommodation and furniture for all new domestic set-ups’. Everything else ‘was distributed in specially organized shops where the purchases of each family would be entered in a general register with a view to attempting a detailed study of the trends in consumption’.23 Had the collective been operating without the constraints of war, it may well have organized the envisaged statistical committee to ‘scientifically balance production and consumption’ and manage local provision of goods to meet needs, as James Guillaume’s 1876 Ideas on Social Organization had proposed.24 Instead a ‘system of compensatory mutual aid’25 was used for exchange in the canton and a barter system was set up to organize exchanges with neighbouring regions. This extended across Aragon and to towns and villages in Levante, Catalonia and Castile.

What really separates individualists from communists? There are perhaps two nagging problems that each identifies in the constitutions of the other. Individualists worry that anarchist-communism seems to demand that individuals curtail their rights to satisfy the communists’ moral commitment to common ownership. But individualists consider it is both reasonable and possible to estimate what each person contributes separately to collective well-being and that justice demands that each is rewarded for their time or labour. That makes it hard for individualists to imagine how communism could be implemented without coercion.

On the other hand, communists reject the elitism of individualists like Yarros and question the basis of the rights individualists rely on to protect equality. They dispute Yarros’s claim that the abolition of the state provided the solution to ‘the labor problem’ or that the legal guarantee of ‘rent, interest, and profits’ was its cause. While communists accept that the state and capital were co-constituted, they did not share the individualists’ view that respect for equal rights would keep differentials in check. They also feared that individualism bred acquisitive cultures. The communist view was that Yarros’s ‘state of freedom’ had a limited shelf life for as long as labour continued to ‘command a price’.26 The most advantaged would eventually attempt to resurrect a state to enforce their rights and guarantee their property. There was another objection, too. Communists questioned the individualists’ assumption that the abandonment of the constitutional guarantee of private property would result in the collapse of capitalism. They thought that individualists tied the persistence of economic slavery too narrowly to the state and this badly underestimated the monopolizing tendencies of capitalism and the power of financial systems. Tucker eventually admitted the miscalculation and Yarros’s turn from individualism to social democracy was another kind of acknowledgement of the problem.

Individualists and communists shared some common ground, but their shared principles – mutual aid, co-operation, freedom and equality – took on different meanings and the nuances were reflected in the constitutions they devised. While it may be hard to imagine Yarros ever having a long conversation with the Platform, it is possible to place Andrade close to the Spanish collectives because of the primacy he gave to equality and the collectivists’ flexibility on issues of individual rights.

The principles distinguishing anarchist-individualist and anarchist-communist constitutions and their degree of overlap

Arguments between anarchist individualists and communists have been complicated by the historical development of anti-statism and egoism in twentieth-century political thought. For many anarchist communists, anarchist individualism, egoism in particular, provides a ground for anti-statist capitalism or anarcho-capitalism. The archetypal individualist is Fernando Pessoa’s anarchist banker: a man who gives up collective struggle for fear of creating new tyranny and chooses instead to amass vast wealth in order to free himself from enslavement to social fictions like the common good or justice.27 Linked to authoritarian forms of free-market liberalism, anarchist individualism thus becomes anti-socialist. Yet the central point is that there is a significant difference between anarchism, whether individualist or communist, and the liberal and republican alternatives. The sociologist Franz Oppenheimer explained the liberal position. Oppenheimer accepted the anarchist analysis of the state as a colonizing force. The ‘villain in the process of history is the Class-State’, he argued. Yet as a ‘real liberal’, he argued that anarchists were wrong to think that it was possible to ‘dispense with a public order which commands the means necessary to maintain the common interest against opposition dangerous to the commonwealth’. Oppenheimer continued: ‘No great society can exist without a body which renders final decisions on debatable issues and has the means, in case of emergency, to enforce the decisions. No society can exist without the power of punishment of the judge, nor without the right to expropriate property even against the wish of the proprietor, if the public interest urgently demands it.’28 Individualists and communists vehemently disagreed. Anarchist constitutions had no such final point of authority as liberals like Oppenheimer believed.

Utopias

There is a strong utopian current in anarchist political thought. Yet many anarchists are wary of the label. As critics of liberal and republican constitutions and opponents of historical materialism, many anarchists have felt impelled to imagine anarchies, but a highly divisive, bad-tempered nineteenth-century debate between anarchists and Marxist social democrats has led many anarchists to associate utopia with blueprints and vain hopes: social conformism, inflexible systems, perfectibility and certainty on the one hand, but escapism and whimsy on the other. Even though it was anarchists like Engländer who condemned the abstract utopias associated with the French Revolution, ‘utopianism’ was the charge that their socialist opponents laid at their door. To a degree, the charge stuck. Today many anarchists defend anarchy as a good idea because it is not a utopia. The anonymous statement Anarchy Against Utopia! is an example:

Anarchy doesn’t have any platform or vision for society. There is no ideal to strive for; no image of what is perfect. As anarchists, we recognize nothing is perfect, not even nature. And it is the imperfections that we embrace, because it is the opposite of striving for an external ideal. Imperfection means diversity and beauty. We realize that whatever type of life we lead, we will not be perfect; and that no matter what type of community we make, it will not be perfect. Whether in a perfect or imperfect society, problems will arise – both large and small. In a perfect society, these problems are all addressed with the same ideal; however, in an imperfect society they can be dealt with as they really are: each problem is different, needing a different solution.29

Anarchists who endorse utopianism typically do so as ‘anti-utopian utopians’, that is as critics of utopian blueprints. This was the argument Marie-Louise Berneri put when she distinguished authoritarian from anarchist utopias. A member of the inter-war London Freedom group and a leading anti-fascist, she argued that anarchists were ‘not concerned with the dead structure of the organization of society, but with the ideals on which a better society can be built’.30 While the reference to ‘dead structure’ describes one anarchist concern, Berneri’s distinction seems too stark. Colin Ward’s later discussion of utopias is more sensitive to the diversity of the utopias anarchists have produced. The straightforward question that utopias pose is ‘How could we or should we live?’31

Responses to this question can take almost any form. A few anarchists have played with the idea of good place/no place central to the literary genre. Louisa Bevington’s Common-sense Country, published in 1896, is a poetic, gently satirical and romantic depiction of a communist utopia that deploys anarchist common sense to deride the incoherence of the existing world order. In ‘Common-sense country’, there is no property market, just housing. People enjoy their daily activities, goods are distributed fairly and everybody lives well:

You never came to a place in any Common-sense city where … you could see … a lot of grain or fish being destroyed on the lunatic excuse that it could not be sold for more than it cost, while … men and women (with their children) [were] hungry, worried, and constantly at their wits’ end, only because they could not buy back the comestibles they had ploughed, reaped, milled, fished, and otherwise laboured to bring within human reach.

Common-sense country is a secular and anti-disciplinary, non-punitive society. It has no churches or temples and no prisons. ‘[T]he sky was holy enough to “sit under”, and even to sing spiritual songs under.’ Life moves at a leisurely pace because time is not money. Schools have been abandoned so that education can flourish. Children’s ‘little, honest, ignorant, simple questions received honest, accurate, and simple answers, in language which they could understand.’ They ‘never needed to unlearn afterwards’. Money has been abolished, too. And this means that there are no kings, police, armies or arsenals, ‘no poorhouses: no brothels, no divorce courts, no nunneries, no confessionals: no “rings”, no strikes, no infernal machines, no gallows’. Nor is anyone in a position to lord it over ‘two, or five, or ten cities, or markets, or communities’. It is a place of honesty and authenticity. ‘[E]ven newspapers expressed real opinions, and conveyed real information.’ And it is libertarian: ‘Every shade of individuality was respected and made welcome, variety being suggestive as well as interesting. No one wheedled, no one canted, no one flattered, or equivocated, or slandered; because none of these were necessary expedients.’ This was indeed a lovely place. Bevington concluded her narrative: ‘There was Peace in Common-sense Country, and Goodwill among men; and Happiness and Fullness of Life had become the Natural Order of the day.’32

One of the best-known anarchist visual images, Paul Signac’s In the Time of Harmony: The Golden Age is not in the Past, it is in the Future, plays with similar ideas. Completed in 1894–5, when anarchist violence reached a peak in Paris and Signac left the capital for the South, the painting uses the Mediterranean landscape to depict ‘anarchist ideals of social harmony, ample leisure and natural beauty’.33 The reference to the Golden Age is an allusion to Eden, but the images are recognizably modern.

These perfected images would doubtless have irritated Yarros, who had no time for ‘utopias, sentimental effusions, and fanciful ideals’.34 Yet it is difficult to paint them either as anarchist ready-mades or what philosopher Martin Buber referred to as a ‘wish-picture’, an expression of unconscious desire, ‘a dream, a reverie’ or ‘seizure’ that ‘overpowers the defenceless soul’.35 Nor were they merely political-programmes-dressed-as-art. Admittedly, Bevington set out many of the principles that underpinned life in Common-sense Country in her 1895 Anarchist Manifesto.36 Following Thomas More, whose sixteenth-century masterpiece Utopia gave rise to the genre, Bevington’s Common-sense Country imagines a not-impossible future.37 Yet unlike More with Utopia, she writes from the position of the no-place that reality obstructs, exemplifying Buber’s conception of utopia as ‘the truth of to-morrow’.38 Her story expresses her personal investment in anarchist goals and it is melancholy and morally charged. Common-sense Country and In the Time of Harmony creatively capture an idea of a better life that millions of people have associated with anarchy. For Bevington and other anarchist utopians, breathing life into anarchist principles is a way of showing that the not-impossible is just that.

The line between a plan and a utopia is hard to draw, but a comment in the Platform hints at the relationship: ‘Anarchism is not some beautiful dream, nor some abstract notion of philosophy: it is a social movement of the toiling masses.’39 There is a practical element in anarchist utopianism as well as a visionary aspect. This was also Martin Buber’s view. In ‘utopian socialism’ he detected ‘an organically constructive and organically purposive or planning element which aims at a re-structuring of society’. In his view, the indicative marker of utopian socialism was that the restructuring would not ‘come to fruition in an indefinite future after the “withering away” of the proletarian dictatorship, but beginning here and now in the given conditions of the present’.40

Enduring utopia

One version of the anarchist utopia is designed to endure. This type is usually projected onto the future and has a strong organizational element. The aim is to imagine viable anarchies that empower individuals while avoiding the ‘dead structures’ Marie-Louise Berneri warned against. As a result, anarchists have tended to be critical if friendly towards Robert Owen, Charles Fourier and Saint-Simon, labelled ‘utopians’ by Marx and Engels. Kropotkin, for example, championed Fourier’s approach to organizing. Shaking a box of stones and letting them organize themselves seemed like a good principle to Kropotkin. Yet he was distinctly unenthusiastic about the regimented communities that Fourier proposed. He thought Fourier’s ‘phalanstery’ (the communal unit of association) was an artificial grouping of representative personality types rather than an organic community. Moreover, Kropotkin thought that Fourier wanted to regulate the activities of its inhabitants too closely.41

It is unusual in anarchist politics to have a comprehensive double-faceted model such as Kropotkin’s. He focused on two issues: first, the need to ensure that struggle resulted in flexible, self-organizing and self-sustaining systems; second, that anti-capitalists had the capacity to conduct protracted revolutionary campaigns against the bourgeoisie. On both counts decentralization and integration were essential.

In Fields, Factories and Workshops Kropotkin outlined his macro-economic plan. It called for the decentralization of production, the abandonment of the division between mental and manual labour, and the amalgamation of agriculture and industry on a regional level. Socialism depended not only on abolishing capitalist production for profit but also on abandoning trade based on the fiction of the free market and the principle of division and exchange.

Kropotkin’s foil here was Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. He argued that it had proposed the disaggregation of production tasks and minute specialization in order to improve efficiency, increase surpluses and boost investment. Kropotkin believed that this model dehumanized workers locally for the sake of a global common good that was ultimately unsustainable. It appeared to Kropotkin that Smith had no sense that labour could and should be fulfilling, even therapeutic. Efficiency trumped all. Implemented in each locality, specialization would condemn workers to a lifetime of mindless, repetitive tasks. Applied internationally, it would encourage clientelism: the supposition that industrialization created a permanent territorial division would transform non-industrialized regions into service economies for ‘advanced’ European states. Efficiency also meant the spread of monocultures and the intensive exploitation of natural resources. The obvious contradiction was that the export of industrial kit by the ‘workshops of the world’ in the medium- to long-term militated against specialization. The spread of industrialization was not only inefficient but unstable. It would inevitably bring sharper rivalry and competition for markets.

In The Conquest of Bread, Kropotkin concentrated on questions of micro-economic change and revolutionary resilience. He called for communes – towns and cities – to prepare to meet the demands of anarchist struggle. The premise of his argument was that supply lines could be secured only by expropriation: the abolition of private property, production for profit and the wages system. In the medium and long term, anarchist communism required the restructuring of production to meet needs. In the immediate short term, it demanded the introduction of systems of distribution based on free exchange. All goods and services – housing, clothing and food – would need to be distributed on the basis of need. With the example of the Paris Commune still fresh in his mind, Kropotkin argued that Parisian workers could withstand a year or two of siege imposed by the ‘supporters of middle-class rule’ if they learned how to draw on their own resources, co-operate and reorganize ‘economic life in the workshops, the dockyards [and] the factories’.42 Witnessing the complete meltdown of the Russian economy after 1917, he realized that this had been far too optimistic. Yet he remained convinced that the prospects for anarchy depended on the ability of local communities to meet their own needs. In 1942 George Woodcock, Kropotkin’s biographer, reiterated the case: ‘if adequate food can be produced only after the economic and social revolution, it is equally certain that a revolution cannot be maintained … A country in revolt, even more a country at war, must provide against a blockade of the most ruthless kind. Revolution without bread is doomed.’43

Kropotkin’s plans were an anarchist response to liberal and conservative forms of internationalism that prevailed at the turn of the twentieth century. The most bullish of these called for the internationalization of markets through the extension of free trade and the corporate globalization of the economy. Liberals saw these moves as guarantees of perpetual peace. The American journalist Harold Bolce, for example, advocated the ‘financial and commercial amalgamation of the nations’, praising the ‘magnates denounced as international pirates’ for giving ‘stability to a world divided by political anarchy’. Where nation states urged ‘races to conflict’, corporations called for ‘combination’. The promise of liberal market internationalism was ‘world-unity greater even than the sovereignty of nations’.44

For Kropotkin, Bolce’s arguments were flimsy. He pointed out that states and corporations worked hand-in-hand and their buccaneering collaboration was the primary cause of inter-state rivalry, instability and war. As an internationalist, he understood anarchy as an outlook and a process, just as Bolce did. But his aim was to push economic forces towards decolonization and to construct non-dominating transnational global communities. Fields, Factories and Workshops opened with an exposé of the colonizing logic of international trade and division:

‘Why shall we grow corn, rear oxen and sheep, and cultivate orchards, go through the painful work of the labourer and the farmer, and anxiously watch the sky in fear of a bad crop, when we can get, with much less pain, mountains of corn from India, America, Hungary, or Russia, meat from New Zealand, vegetables from the Azores, apples from Canada, grapes from Malaga, and so on?’ exclaim the West Europeans. ‘Already now,’ they say, ‘our food consists, even in modest households, of produce gathered from all over the globe. Our cloth is made out of fibres grown and wool sheared in all parts of the world. The prairies of America and Australia; the mountains and steppes of Asia; the frozen wildernesses of the Arctic regions; the deserts of Africa and the depths of the oceans; the tropics and the lands of the midnight sun are our tributaries. All races of men contribute their share in supplying us with our staple food and luxuries, with plain clothing and fancy dress, while we are sending them in exchange the produce of our higher intelligence, our technical knowledge, our powerful industrial and commercial organising capacities! Is it not a grand sight, this busy and intricate exchange of produce all over the earth?’45

For Kropotkin, this exploitative exchange, rooted in domination, could never be altered by the globalization of the international capitalist market, or any rebalancing of corporate over state control. By contrast, anarchist internationalism would mean that regions and nations (understood in the ‘geographical sense’ rather than the geopolitical) would exchange only ‘what really must be exchanged’. The restriction would reduce the volume of trade while ‘immensely’ increasing ‘the exchange of novelties, produce of local or national art, new discoveries and inventions, knowledge and ideas’.46 The emergence of global scientific knowledge or Erdkunde from local practice and experience or Heimatkunde would enable peoples in each region to determine how they wanted to live, applying insights gained from non-dominating exchanges to reduce the burdens of labour. Like many nineteenth-century socialists, Kropotkin expected the working day to be slashed by the intelligent use of technology. But he also thought that the mode of production would change. Anarchy would reinvigorate the petty trades – artisan crafts – because this kind of work was more rewarding than factory labour. The expansion of market gardening was one of his particular hobbyhorses; greenhouse technologies would enable year-round production and extend growing seasons in harsher climates. The use of wind and solar power would facilitate the creation of industrial villages. Kropotkin did not promise universal happiness, which, he said, was well beyond the scope of anarchy. Anarchist internationalism was a more modest rational plan, just and sustainable. It encouraged peoples to work co-operatively with ‘their own hands and intelligence’ and with the ‘aid of the machinery already invented and to be invented’ to ‘create all imaginable riches’. Its ethic was do not ‘take … bread from the mouths of others’.47

Kropotkin’s utopia is controversial among some post-left and postanarchists, both because it assumes that technologies can be detached from the conditions of their production, and because it seems teleological. Kropotkin not only outlined a programme for change, but also appeared to suggest that his integrated economy was already progressing. The future, he argued, is ‘already possible, already realisable’ for ‘the present’ was ‘already condemned and about to disappear’.48 Even if he left room for the exercise of will, Kropotkin seemed to indicate that history was on the anarchists’ side.

The distinction between probability and possibility drawn by sociologist Deric Shannon offers a different interpretation. Probability speaks to existing configurations of power and possibility is about resistance to them. ‘It seems much more probable’, he argues, ‘that capitalists will either bring us to ruin through some nuclear disaster or through environmental devastation, than that humanity will wage a successful war on capitalism’s institutions of profit-making-at-all-costs and end the separation of humanity into competing nations based on glorified lines drawn on a map.’ Yet it is still possible to find ‘plenty of reasons to support anticapitalist efforts and engage in those efforts ourselves’.49 By insisting that economic trends were as supportive of anarchist internationalism as of its regressive forms, Kropotkin invited his audience to weigh one utopia against the other and consider which was really the most enduring.

Transitory utopias

The world has changed dramatically since Kropotkin’s time. As the political philosopher Takis Fotopoulos notes, the ‘present internationalization is qualitatively different from the earlier internationalization’. The latter had been based ‘on nation-states rather than on transnational corporations’. Commodity and financial markets are now much larger and play a ‘crucial role in determining the “agent” of internationalization’ and the ‘degree of the state’s economic sovereignty’.50 Similarly, while Kropotkin was in the forefront of early twentieth-century debates about climate change and its associated migratory pressures, looming ecological collapse was not at the top of his agenda, as it is today for many anarchists. It is not surprising, then, that most influential modern anarchist utopias differ to Kropotkin’s, especially when it comes to ecology and technology, and that some are imagined as fleeting possibilities rather than enduring alternatives.

Published in 1983, Hans Widmer’s anti-capitalist utopia, bolo’bolo, is an example. The framing and language seem designed to highlight the fantastical, otherworldly quality of the utopia he imagines. Writing under the pseudonym P.M., Widmer opens the work with a critique of civilization. This is presented as a story and it plots the shift from nomadic ways of living during the Old Stone Age 50,000 years ago, to horticulture, animal-farming, land protection, settlement and ritual. Hierarchy and domination and the regulation of work followed. Heightened by industrialization, the repressive tendencies of civilization centre on the expanding ‘Work-Machine’ and ‘War-Machine’. These have wrought planetary destruction: ‘jungles, woods, lakes, seas’ are ‘torn to shreds’; ‘our playmates’, non-human animals, have been endangered or ‘exterminated’ and the air has been polluted by ‘smog, acid rain [and] industrial waste’. The machines have emptied the ‘pantries’ of their ‘fossil fuels, coal, metals’ and prepared for ‘complete self-destruction’ through nuclear holocaust. The inability of the Work-and-War Machine (also called the Planetary Work-Machine) to provide for the earth’s human populations has made some people so ‘nervous and irritable’ that they are ready for the ‘worst kind of nationalist, racial or religious wars’. War appears a ‘welcome deliverance from fear, boredom, oppression and drudgery’.51

The Machine is ‘planned and regulated’ by corporations and international trade and finance. There are no central organs of power. Instead, the Machine exploits the tensions between workers and capital, public and private provision, sexes and genders in order to ‘expand its control and refine its instruments’. Workers employed as ‘cops, soldiers, bureaucrats’ run the ‘truly oppressive organs of the Machine’. Mostly white, male technical-intellectual workers, concentrated in the US, Europe and Japan, are placed at the apex of the Machine. Industrial workers, both male and female, who predominate in eastern Europe and Taiwan, are parked in the middle. Fluctuant workers, those without regular employment or income, composed mainly of women and non-whites living in African, Asian and South American shanty towns, are slumped at its foot. The Machine also runs international chain gangs. ‘Turkey produces workers for Germany, Pakistan for Kuwait, Ghana for Nigeria, Morocco for France, Mexico for the US’. Division and specialization mean that each cog daily serves as its own slave-master:

You spend your time to produce some part, which is used by somebody else you don’t know to assemble some device that is in turn bought by somebody else you don’t know for goals also unknown to you. The circuit of these scraps of life is regulated according to the working time that has been invested in its raw materials, its production, and in you. The means of measurement is money. Those who produce and exchange have no control over their common product, and so it can happen that rebellious workers are shot with the exact guns they have helped to produce. Every piece of merchandise is a weapon against us, every supermarket an arsenal, every factory a battleground. This is the mechanism of the Work-Machine: split society into isolated individuals, blackmail them separately with wages or violence, use their working time according to its plans.52

Resistance is possible and within limits allowed, but it is futile. Oppositional forces are either neutralized through recuperation or repression. ‘The Machine is perfectly equipped against political kamikazes, as the fate of the Red Army Faction, the Red Brigades, the Monteneros and others shows. It can coexist with armed resistance, even transform that energy into a motor for its own perfection.’53

Utopian planning might seem an obvious route out of this wretchedness, but Widmer disagrees. Instead he seeks to learn from the past. Utopia is the last resort of the miserable, destined to replicate the conditions of their own misery. Remembering how the industrial horrors of the nineteenth century spurred on utopian hopes for the future but only extended enslavement, he warns: ‘Even the working-class organizations became convinced that industrialization would lay the basis of a society of more freedom, more free time, more pleasures. Utopians, socialists and communists believed in industry.’54 Widmer concludes that the limits of utopia are inescapable because our alternatives are constrained by our reality. ‘Dreams, ideal visions, utopias, yearnings, alternatives’ are ‘just new illusions’. If we rely on these, we will only be seduced ‘into participating in a scheme for “progress”’. History teaches that any projected futures we dream up will be ‘the primary thought of the Machine’.55

The answer is to create a second reality. This reframes Colin Ward’s question by asking ‘How would I really like to live?’ in an entirely subjective way. We should think about the immediate future, not some prospective alternative and it is not a question about reality but about understanding individual desires, regardless of their practicality.

bolo’bolo is the second reality. It works globally and locally through subversion (rather than attack) plus construction: a strategy Widmer calls substruction. Its success depends on the development of ‘dysco knots’ through three forms of direct action: ‘dysinformation’, ‘dysproduction’ and ‘dysruption’. These take shape outside workplaces in spaces that the Machine does not completely regulate and through encounters between people who are otherwise divided. They ‘attempt the organization of mutual help, of moneyless exchange, of services, of concrete cultural functions in neighborhoods’ and ‘become anticipations of bolos’.56 These expand into macro-level ‘trico-knots’, bringing geographically dislocated neighbourhoods into direct relation with each other. Trico-knots have a moneyless exchange function, first for ‘necessary goods’ like ‘medicine, records, spices, clothes, equipment’, but also for cultural enrichment. For example, those involving predominantly Technical and Fluctuant workers ‘will give a lot of material goods (as they have plenty), but they’ll get much more in cultural and spiritual “goods” in return; they’ll learn a lot about life-styles in traditional settings, about the natural environment, about mythologies, other forms of human relations.’57

The ‘bolo’ is the principal social unit emerging from all this activity. The bolo expands to create a ‘patchwork of microsystems’ (‘bolo’bolo’), each with 300–500 ‘ibus’, imperfect beings tortured by the reality of the Machine. The bolo is an ecological survival strategy underpinned by an agreement or ‘sila’ for ‘living, producing, dying’. It guarantees survival, conviviality and hospitality to each ibu by abandoning money as the medium for social interaction and it uses ‘asa’pili’, an artificial language, to facilitate universal communications without domination.

The sila guarantees each ibu with ‘taku’. Widmer contends that individuals have a need for private property and the taku satisfies this. It is a 250 litre volume storage container for personal items, ‘unimpeachable, holy, taboo, sacrosanct, private, exclusive, personal’. The sila also provides ‘yalu’ (a daily ration of 2,000 calories-worth of local food), ‘gano’ (a minimum of one day’s housing in any bolo) and ‘bete’ (medical care). To facilitate movement, each bolo must provide hospitality for up to fifty visitors, each ibu being a potential guest. The adoption of ‘fasi’, or borderlessness, means that ibus are free to come and go as they please and cannot be expelled. Ibu also have ‘nugo’ – a suicide pill for use anytime and a right to demand aid to dispatch themselves.

Sila includes ‘nami’, the right of ibus ‘to choose, practice and propagandize for its own way of life, clothing style, language, sexual preferences, religion, philosophy, ideology, opinions, etc., wherever it wants and as it likes’. In turn, nami is realized through the diversity of the ‘nima’ or the ‘territorial, architectural, organizational, cultural and other forms or values’ of the bolos.

As any type of nima can appear, it is also possible that brutal, patriarchal, repressive, dull, fanatical terror cliques could establish themselves in certain bolos. There are no humanist, liberal or democratic laws or rules about the content of nimas and there is no State to enforce them. Nobody can prevent a bolo from committing mass suicide, dying of drug experiments, driving itself into madness or being unhappy under a violent regime. bolos with a bandit-nima could terrorize whole regions or continents, as the Huns or Vikings did. Freedom and adventure, generalized terrorism, the law of the club, raids, tribal wars, vendettas, plundering – everything goes.58

Widmer contends that bandit-nima are unlikely: the possibility is explained as part of the hangover of the Machine. ‘Alco-bolo’, ‘Indio-bolo’, ‘Krishna-bolo’, ‘Sado-bolo’, ‘Soho-bolo’ are among the nima he imagines taking shape. He labels nima ‘pluralistic totalitarianism’ but they give bolo’bolo a panarchistic flavour. In practice, of course, nami depends on the nima of the bolos. Because no bolo and no ibu is like any other compromises have to be made. ‘Every ibu has its own conviction and vision of life as it should be, but certain nimas can only be realized if like-minded ibus can be found.’59

There are a number of other limits on sila. ‘Munu’, honour or reputation, ensures compliance with the hospitality rule, but there is an exception here, too. Where guests constitute more than 10 per cent of the bolo, the bolo can refuse sila. In addition, the freedom of ‘yaka’, a carefully regulated code allowing ibu to challenge other ibu or groups of ibus to duels, suggests that all the terms of sila are limited. Widmer argues that the survival of bolo’bolo depends principally on a critical mass of ibus deciding to take part. If too many decide not to, then money economies are likely to return. There are no other serious social threats because the personal contacts fostered by bolo’bolo. Once money is abandoned, the Machine’s unnatural enforcement agencies ‘police, justice, prisons, psychiatric hospitals’ also ‘collapse or malfunction’. Widmer comments that nobody remains to ‘catch the “thief”’ and ‘everybody who doesn’t steal is a fool’.60 At the same time, he also observes that bolo’bolo encourages self-policing and the adherence to local moral norms.

Bolos take root in existing spaces – towns, across rural settlements – and across geographical areas – groups of islands, for example. They can also emerge from fluid interactions of seafaring or other nomadic folk. Forming a ‘patchwork of micro-systems’ collections of ten to twenty bolos can combine to form larger co-ordinating bodies at local, sub-regional and autonomous regional levels. These larger units, ‘tega’, ‘vudo’ and ‘sumi’, are organized by a set of formal rules to ensure accountability to the bolos. For example, tega take responsibility for infrastructural projects and run ‘dala’ or decision-making assemblies composed delegates from the bolos and external observers or ‘dudis’ from other tega.

Self-sufficiency in basic foods underwrites the self-determination and self-governance of the bolos. Each bolo practises a general culture of ‘kodu’, or agricultural production. The priority attached to kodu, as a means of establishing the ibus’ relationship with nature, tends towards the integration of urban and rural areas, the depopulation of larger cities and the repopulation of villages. Bi- or multilateral agreements facilitate the procurement of foodstuffs that bolos either cannot produce or prefer not to. Kodu depends on ibu commitment, approximately 10 per cent of each ibu’s time. This may be experienced psychologically as work or pleasure, depending on the proclivities of individual ibu. The potential burdens kodu entails are offset by ‘sibi’, the production of non-foodstuffs, which is typically an expressive, creative, pleasurable activity. Gift-giving and carefully controlled markets are used for exchange, enabling ibus to satisfy their need for personal property.

Bolos benefit from integrated energy systems and ecological waste recycling. In cold zones, Widmer estimates that bolos achieve between 50–80 per cent energy independence. Water consumption is reduced by changes in industrial production and the shift from the ‘disciplinary functions of washing’ that white-collar work and suburban living foster. Other gains are made as a result of the changes in knowledge production. The disappearance of ‘centralized, high-energy, high-tech systems’ makes ‘centralized, bureaucratic, formal science’ redundant but it does not result in the end of science. There is ‘no danger of a new “dark age”’. The time that ibus have at their disposal means that ‘the scientific, magical, practical and playful transmission of capabilities will expand considerably’. Everyone will be a professor. ‘There will be more possibilities for information and research; science will be in the reach of everyone, and the traditional analytical methods will be possible, among others, without having the privileged status that they have today. The ibus will carefully avoid dependency upon specialists, and will use processes they master themselves.’61

Much of the detail of bolo’bolo resonates with Kropotkin’s utopianism. The fundamental difference is that Widmer builds instability into his projections. bolo’bolo ultimately fails and domination returns. The problem stems from a mutation in the cultures of non-domination that bolo’bolo fosters. After 358 years an epidemic (‘the whites’) spreads, overwhelming the other bolos. A period of contemplation and chaos lasting just over 400 years ensues until ‘Tawhuac puts another floppy disc into the drive.’62

How is bolo’bolo a transitory utopia? In many ways it looks as enduring as Kropotkin’s revolutionary commune model. Unlike Kropotkin, Widmer does not include a lot of statistics to support the feasibility of the project but the utopia is described in extraordinary detail. Widmer also includes a provisional schedule: bolo’bolo is projected to come into being within three to five years. The substraction starts in 1983. The first planetary convention, ‘asa’dala’ meets in 1987. bolo’bolo begins in 1988.

In part, the difference is stylistic. bolo’bolo is written as fantasy. Fields, Factories and Workshops is social science. A second difference is the relationship of the utopia to the practice. Hakim Bey calls bolo’bolo a permanent autonomous zone (PAZ), that is, a temporary autonomous zone (TAZ) that has succeeded in ‘putting down roots’. More than a thought-experiment but less than a plan, bolo’bolo is an insurgency that exists in time and space while avoiding all ‘permanent solutions’.63 It is about liberation for a while, not revolution and restructuring for good. Kropotkin’s utopia was for keeps, in the sense that the practice of communism was intended to support a system of self-regulation that would prevent the return of capitalism and the state.

Bey prefers the transitoriness of bolo’bolo. It conforms to Stephen Pearl Andrews’s idea of the unlegislated dinner party that also inspired Yarros and it imagines spaces that exist within the legislated parlour.64 Bey uses two examples to illustrate where the line between enduring and transitory utopias should be drawn. On the one hand, he finds features of TAZ in the 1919 Munich Soviet. Here, the expectation of its crushing (which right-wing paramilitaries soon made certain) encapsulated the aims of the rising more exactly than the revolutionaries’ professed aim, which was to achieve lasting change. On the other hand, Bey contends that Makhno’s revolution was ‘meant to have duration’. It did not last a long time, but it was ‘organized’ for this purpose.65 No features of TAZ were present here. The intentionality Bey describes points to a third difference, namely about the quality of space that enduring and transitory utopias are designed to create. In his history of German-American anarchism, the historian Tom Goyens comments that anarchists ‘did not simply occupy space; they consciously produced it by appropriating places for themselves and inscribing them with meaning that reflected their ideology and identity’.66 The anarchists who created these spaces in a plethora of bars and clubs typically looked outwards. Their visions were unrestrained. bolo’bolo describes the possibility of survival for everyone but it is constructed as an inward reflection on the control that the Planetary Work-Machine exercises on spaces of liberation.

Democracy

Anarchists have often been ambivalent about democracy. Their doubts arise from the power inequalities that democracy regulates. Even in genuinely liberal regimes, where democracy is defended both as a value and a process, many anarchists argue that it serves essentially repressive ends. This is Yarros’s argument and it is also presented in the Makhnovist Platform. A section titled the ‘Negation of Democracy’ distinguishes the liberal principles which democrats promote from the reality of democracy’s institutional operation. Democracy lauds ‘freedom of speech, of the press, of association, as well as equality before the law’ but it ‘leaves the principle of capitalist private property untouched’. It thereby ‘leaves the bourgeoisie its entitlement to hold within its hands the entire economy of the country, all of the press, education, science and art’. Democracy ‘is merely one of the facets of bourgeois dictatorship, concealed behind the camouflage of notional political freedoms and democratic assurances’.67