THE BATTLE FOR EUROPE

By midnight on 17/18 June, the Prussian army had reunited in and around Wavre. It had lost around 30,000 men in the fighting before Ligny, at Ligny itself and in desertions after the battle. Ziethen’s I Corps had been the worst mauled and Pirch’s II Corps had also taken considerable casualties. Thielemann’s III Corps was already engaged as the rearguard, so Bülow’s IV Corps, uninvolved in the battle at Ligny and thus up to strength and with all its equipment, was the obvious corps to lead the move towards Waterloo. Gneisenau, Blücher’s chief of staff, issued orders during the night instructing Bülow to leave at first light and head for Chapelle Saint-Lambert, seven miles from Wavre. He would be supported and preceded by Colonel von Schwerin’s 1st Cavalry Brigade (like all Prussian brigades, actually the size of anyone else’s division). Once there, he was to deploy into battle formation and could either deploy on Wellington’s left flank, or attack the French right, depending upon the situation when he got there. Next to go would be Pirch’s II Corps and finally Ziethen, leaving Thielemann to ensure that there was no interference from Grouchy.

On the face of it, Bülow – despite the fact that his starting point was three miles south-east of Wavre and so he was further away from Waterloo than the other Prussian troops – should have been able to reach Chapelle Saint-Lambert in five hours, but there were all sorts of problems in his way. First, he had to get across the River Dyle, and there was only one narrow bridge. Second, he had to wind his way through Wavre, which his lead troops eventually reached at around 0700 hours and where there was traffic gridlock with ammunition wagons, ambulances, ration carts and all the other wheeled impedimenta of an army clogging up the narrow roads. It got worse, for a fire broke out in the town – whether it was caused by an ammunition wagon exploding or by Prussian cooking fires getting out of control is unknown – making progress even slower than it already was. Once out of Wavre, the country was hilly, crossed only by farm tracks and with numerous ravines and stream valleys to cross. Although the rain had stopped, the ground was boggy and slippery, making it very difficult for the horses to pull the guns uphill and impossible for them to hold them on the way down. The horses had to be unhitched and the guns attached to tow ropes and lowered downhill by soldiers. Eventually, the heaviest guns, a battery of twelve-pounders, were abandoned. All this took time, and as the only maps the Prussians had were very rough sketches produced in haste by the British Royal Engineers, navigation too was a problem. It was 1000 hours before Bülow’s last formation, Major General von Ryssel’s division-sized 14th Infantry Brigade, could leave Dion-le-Mont, and then he had to drop off two battalions of infantry and a regiment of hussars from Schwerin’s brigade to hold off Exelmans’ cavalry, which was now biting at his heels, until he got across the Dyle.

Schwerin’s cavalry reached Chapelle Saint-Lambert and then pushed on through Lasne and into the Bois de Paris, from where the corps could either go north-west to join Wellington, whose left flank was about one-and-a-half miles away, or strike the French right, at about the same distance. It was here at about 1430 hours that the Prussians suffered their first casualty of the Battle of Waterloo when Colonel von Schwerin, up with his leading squadron of cavalry, skirmished with some scouting French cavalry and was killed by a shot from a horse artillery gun. Then, from around 1530 hours onwards, the units of Bülow’s corps began to arrive in the Bois de Paris, while the leading elements of Pirch’s corps headed towards the Anglo-Dutch left flank.

Earlier at Le Caillou, over breakfast, Napoleon had discussed the forthcoming battle with his staff and senior commanders. His original intention had been to start operations at first light, but during the night this had been put back several times, eventually to 0900 hours, and even this start time was about to be postponed. Many accounts say this was because Major General Ruty, commanding the army’s artillery, supported by Drouot, the commander of the Imperial Guard and another gunner, protested that the ground was too wet to allow deployment of the guns and that, even if they could by much effort and sweat of man and horse be deployed, the round shot would bury itself in the soft ground at the first strike, instead of skipping along the surface and taking out file after file of enemy soldiers. This is most unlikely. Napoleon, himself a gunner, did not need anyone else to tell him the effect of wet ground on artillery. The real reason was surely that his army was not ready, and in some cases not even present by 0900 hours, and he could not begin the battle until it was. The French battalions were still struggling up the only road, and, although it was no longer raining, the going was still very heavy and on arrival men needed to dry their weapons and equipment and snatch a hurried meal.

As it was, at around 1100 hours Napoleon issued his final battle orders, which were to the effect that, after an initial softening up by the artillery of the Grand Battery, d’Erlon’s infantry would attack the Allied left centre, followed by Lobau’s corps and the Imperial Guard, which would punch a hole through Wellington’s line, knock this Anglo-Dutch rabble out of the way and march on to Brussels. The attack was to begin on a signal given by Marshal Soult, the chief of staff, and d’Erlon’s attack was to be preceded by a diversionary attack on Hougoumont. This latter was a perfectly sound plan: if Wellington’s right were threatened, the duke would have to reinforce it, and he could only do that, so the Napoleonic logic went, by moving troops from his centre, thus weakening it for d’Erlon’s attack. But warnings by Soult, Ney, Reille and others who had fought Wellington in the Peninsula that it was unwise to attack British troops in a defensive position head-on were swept aside – they had all been beaten by Wellington and so were afraid of him, whereas Wellington was a bad general and the English were bad troops. The whole affair, claimed the emperor, would be no more difficult than eating one’s breakfast.

The artillery of the Grand Battery, positioned in front of Quiot’s and Donzelot’s divisions, consisted of the Imperial Guard’s artillery reserve of eighteen twelve-pounders, d’Erlon’s six twelve-pounders, the forty six-pounders from the cavalry divisions, and the divisional artillery of Quiot and Donzelot, another twelve six-pounders. There is some debate about exactly how these guns were drawn up. To be effective as a battery, the guns needed to be reasonably close together, but they could not be positioned wheel to wheel or there would be no room for the infantry and cavalry to move through them. Assuming twelve feet wheel to wheel between guns, eighty guns would take up a frontage of 475 yards, so it is possible that the guns were positioned in two ranks in which the rear gun line was made up of the twelve-pounders placed along the track that ran along the French front (and eventually to Papelotte farm), with the lighter six-pounders further down the hill in front. Overhead fire was not normally practised (although the British had used it at the siege of San Sebastián in Spain), but this may have been the only way to make the battery manageable without restricting the movement of the infantry and cavalry. In whatever formation the battery was deployed, however, the number of men, horses (480 just to pull the guns, never mind officers’ chargers, horses to pull wagons, farriers’ forges and the like), limbers and wagons of extra ammunition would have caused an enormous problem in traffic control, and it seems likely that the limbers and the horses were positioned behind d’Erlon’s infantry on the reverse slope.

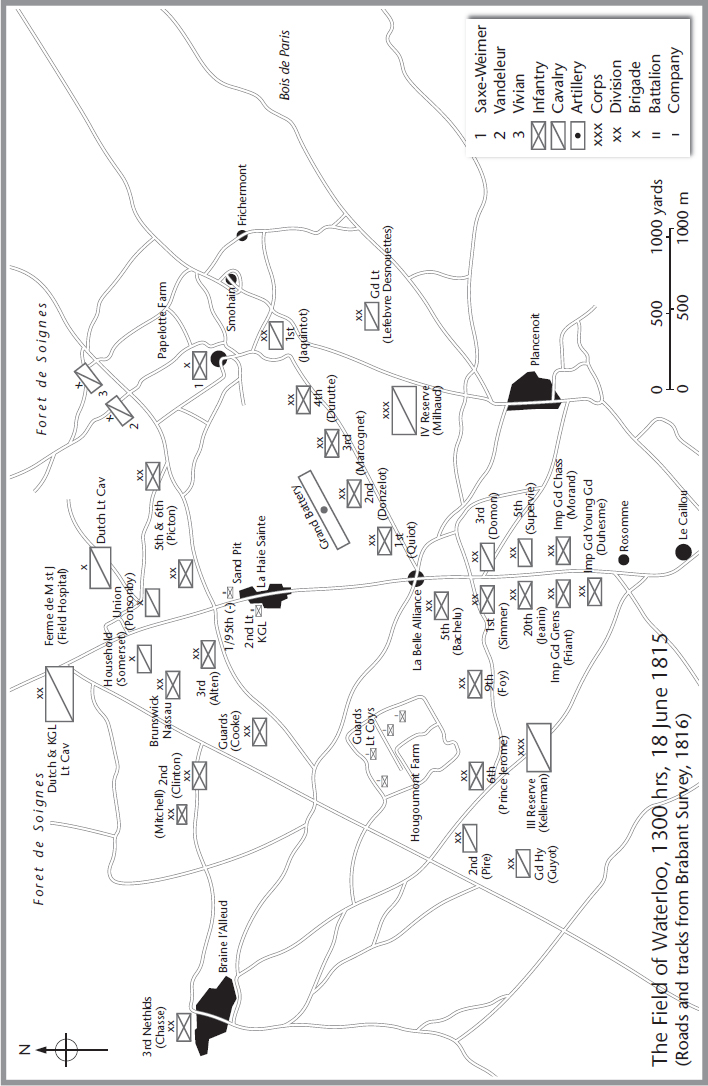

Contemporary accounts of Waterloo give widely differing times for the start of the action. Partly this is because many participants would have known only what was happening on their immediate front – and there was much unharvested maize and rye to restrict vision until it was eventually trampled down – and also because watches were expensive and only officers had them, and then only those who could afford such a luxury. There were, of course, no BBC pips to set the watch by and owners checked with the sun – it was 1200 hours when the sun was at its highest, although views on when the sun was actually highest in the sky could vary by two hours or more either way. Strangely, perhaps, there seems to have been no attempt to synchronize watches, as would be done today. We do know that Napoleon’s final battle orders were timed by Soult at 1100 hours. Given that it would take around two hours for them to be promulgated to all units and for any final dispositions to be sorted out, and that Napoleon then inspected his army drawn up on the forward slope, it would seem very unlikely that anything happened much before 1300 hours and it was probably later – although there was some scrapping between Durutte’s skirmishers and those of Saxe-Weimar on the French extreme right, almost certainly much earlier than that.

When the emperor had taken up his position of observation on the high ground just south-east of the Belle Alliance estaminet, the French artillery began its preliminary bombardment. As Wellington’s infantry was on the reverse slope, there was little for the gunners to aim at, but they did not need a specific target: as long as their shot and shell landed just over the Anglo-Dutch ridge, they were bound to hit something. On the Allied left, a frontage of 1,800 yards, stood six brigades totalling just over 14,000 men. Allowing for officers and supernumeraries, that gives around eight men per yard of front, which means that battalions of infantry would almost certainly be deployed in close column of companies. A British battalion so formed would have nine companies of eighty men each in line of two ranks, the companies positioned behind each other with thirty yards between them. The tenth company, the light company, would, initially at least, have been forward of the ridge in skirmish order. Dutch-Belgian battalions had a different establishment to that of the British, but the principle was the same. The point is that there were a great many people spread out to a considerable depth behind the ridge: very roughly, there was an area 1,800 yards long by 270 yards deep that was occupied by men, and, although all were ordered to lie down, it would have been difficult for the French artillery not to do some damage as long as its shots hit somewhere in that rectangle. The mathematics for the Allied right flank with its six brigades shows six men per yard of front, so the occupied rectangle was shallower, but there was still a very large area for the French gunners to drop their shots into.

As it happened, the achievements of the artillery bombardment seem to have been mixed. Some battalions suffered considerably, whereas others seem to have escaped unscathed. According to a soldier of the 71st Foot, in Adam’s brigade behind the Guards and across the Nivelles road, the bombardment went on for an hour and a half and cost the battalion sixty men.32 Lieutenant John Kincaid, adjutant of the 95th Rifles, himself behind the ridge near the crossroads, with three of his companies forward in the sand quarry, says that a cannon-ball ‘from lord knows where for it was not fired at us’ took the head off his right-hand man, but does not mention the bombardment further.33 Many contemporary accounts do not mention it at all. The bombardment appears, however, to have gone on for about half an hour – although to those under it, like that soldier of the 71st, it would obviously have seemed much longer – and overall does not seem to have had much effect. This is perhaps surprising, given the extensive target area, but may have been due to the decline in the standards of French artillery. Charles de Gaulle, in an historical résumé of the French army, pointed out that many guns had been left behind in Russia, and others had been lost in the battles of 1813 and 1814.34 Furthermore, by 1815 the armaments industry was poorly paid and inefficient, leading to substandard workmanship. Other contributory factors would have included the use of unseasoned wood in the manufacture of trails and gun carriages and the difficulty of getting enough skilled gunners and suitable horses, particularly for the twelve-pounders. As well as the decline in capability and equipment, the Allied troops’ positions on the reverse slopes, the height of the crops, at least before they were trampled down, and the dense clouds of smoke that would have hung about on that windless day would have made it difficult for the battery commanders to correct their aim based on fall of shot – which they could not see. Many of the rounds expended must therefore have fallen on the forward slope or, as an officer in Picton’s division remarked, have gone over the heads of the troops, who, apart from the mounted officers, were lying down.

With the artillery bombardment underway, the diversionary attack on Hougoumont farm could now begin, while d’Erlon’s infantry readied themselves for an attack on the Allied left centre once Wellington had weakened it by a transfer of troops to the right flank. The diversion was entrusted to the extreme left-hand French division, that of Prince Jérôme, who despatched Brigadier General Pierre-François Bauduin’s 1st Brigade of seven battalions of light infantry, who were to advance due north through the wood and attack the orchard and garden wall and the south gate. Aged forty-seven at Waterloo, Bauduin had joined the revolutionary army as a lieutenant in 1792 and was promoted to major and given command of a battalion on the field of the Battle of Marengo in 1800, where he was wounded. After two years in ships under Admiral Villeneuve, he returned to the land service before the Battle of Trafalgar, became a colonel in 1809, served in the Russian campaign and was promoted to brigadier general in 1813, before taking part in the battles in northern Europe in 1813 and 1814. Decorated by Louis XVIII, he nevertheless returned to his old allegiance on Napoleon’s return from Elba.

Four thousand men, led by Bauduin, tramped down the slope and into the woods. They had little trouble in chasing out the Lüneberg and Nassauer skirmishers, who were there more as an early-warning trip wire than as a serious defence line. Twenty yards from the south gate of Hougoumont farm, the trees abruptly ended in flat open ground. This was a killing ground for the guardsmen and the Germans in the farm and the orchard – at that range even the notoriously inaccurate smooth-bore musket could not miss, and from every window and every loophole in the walls and roof, and from the firing platform behind the orchard wall, there came a hail of fire. Behind every firer were two or three men loading muskets and passing them forward, and the first rush of French soldiers from the tree line got nowhere, the dead and the wounded littering the open ground between the farm and the trees. Very soon a dense cloud of black smoke obscured both objective and target, but all the defenders had to do was to fire into the smoke and they were almost bound to hit someone. Not only was there an unceasing rattle of musketry for the French to cope with, but also Major Robert Bull’s Royal Horse Artillery battery of six howitzers on the ridge was dropping its shells in the woods: to run forward meant death by musket ball, to retreat risked death by shell. Showing great courage but perhaps little intelligence, the French kept coming on and kept running into a storm of lead from the defenders. A few lucky men who managed to get as far as the wall were bayoneted trying to climb over it, and when Bauduin himself was killed, the attack petered out. A painting in a Waterloo museum shows the gallant general emerging from the wood line, mounted on his horse and his sword drawn. While we do not know for certain, it is very unlikely that Bauduin would have ridden through the wood, and far more likely that he would have come through on foot, with his horse led by an orderly somewhere behind him. Withal, the result was the same, and to this day there is a plaque on the orchard wall commemorating the first general to die at Waterloo.

The first brigade having failed, Prince Jérôme now launched his second brigade, another six battalions of 3,500 men under Brigadier General Jean-Louis Soye, who, scooping up the survivors of Bauduin’s brigade on the way, showed a little more finesse this time by going west, outflanking the farm and assaulting the northern gate, which was open. Leaving the gate open was not as daft as it sounds, as the avenue to the farm’s main entrance – which this was – constituted the route by which resupplies of ammunition could be delivered and the wounded removed. There was, apparently, a wagon driver – he may have been named Brewer or Brewster,* and he may have been a soldier of the Royal Wagon Train (the ‘Newgate Blues’†) or a civilian under contract to the commissariat – who most courageously drove a wagon up and down from the crest to the farm, in through the northern gate; here he would hurl casks of musket ammunition out of his wagon, take on board wounded, and gallop, or more probably fast-trot, back up the hill.

Fighting on the west side of the farm was severe, with the remnants of Bauduin’s 1st Légère (light infantry) trying to get to the open gate. The regimental commander, Colonel Amédée Louis Despans-Cubières, who had assumed command of the brigade when Bauduin was killed, was well to the fore, still on his horse and slashing at the red-coated guardsmen with his sabre. Cubières, at twenty-nine one of the younger regimental commanders, was an aristocrat who survived the Revolution (his father was a marquis and had been imprisoned for a time). He enlisted as a private in 1802, was commissioned in 1804, and made rapid progress upwards, helped by having three horses killed under him in Russia, after which he went from captain to colonel in one year, 1813. Eventually he slashed at one man too many, the sergeant major of the 2/3rd Guards, Ralph Fraser, a native of Glasgow who had enlisted in 1799. Fraser unhorsed Cubières, seized his horse and dragged it into the farmyard. Cubières, who went on to become a major general under the July monarchy and died in 1853, always claimed that Fraser had spared his life out of human decency. The truth almost certainly is that bagging a good French horse was of far more interest to Fraser than killing its rider.

On this occasion, some of Soye’s men did manage to get into the yard of the farm through the open gate. Their leader was a second lieutenant of pioneers whose name is given as Legros, although whether this really was his name or a nickname (by all accounts he was a giant of a man) we do not know. He is also referred to as L’Enfonçeur, ‘the enforcer’, which undoubtedly is a nickname and he was armed with a pioneer’s axe. Storming into the yard swinging his axe and followed by French infantry, he might have made a difference had he been able to keep the gate open long enough for enough men to tip the balance to enter, but the situation was saved by Captain Macdonnell, who spotted the danger and with two other officers and a handful of NCOs forced the gate closed. Now it was a bar-room brawl, with fists, musket butts, bayonets and belts, until all the forty or so Frenchmen who had penetrated the courtyard were dead or dying. Only one survived: a drummer boy whom the guardsmen thought too young to kill and who spent the rest of the day sitting in a corner weeping – not because of the blood and mayhem all around him, but because a guardsman had put his boot through his drum.

Instead of being the diversion that it was supposed to be, the attack on Hougoumont now became an end in itself that sucked in more and more French troops to no avail. Occasionally a particularly vigorous assault might get some men into the orchard, whereupon one or two companies from the garrison’s parent battalions on the ridge would be sent down to chase them out and restore the situation; if the French ever did look likely to take the whole complex, then troops from the nearest brigades were sent down and recalled when the danger had passed. At one stage the farm was set on fire, a dangerous situation for the defenders and one that prompted Wellington to send a message to Macdonnell. Written in pencil on donkey skin,* it said:

I see that the fire has communicated from the Hay Stack to the roof of the Chateau. You must however keep your Men in those parts to which the fire does not reach. Take care that no Men are lost by the falling in of the Roof or floors. After they will have fallen in occupy the Ruined walls inside of the Garden; particularly if it should be possible for the enemy to fire though the Timbers in the Inside of the house.†

Legible, perfectly punctuated even down to the use of the semicolon, and, apart from the proliferation of capital letters, grammatically accurate, the memo shows Wellington’s extraordinary ability to remain calm and focused when all around him was noise and confusion.

Most sources suppose that the fire was started by a French shell, although it is perhaps more likely that it was caused by one of Major Bull’s shells dropping short or simply by burning musket wads falling on the straw or hay that littered any farmyard. There was a haystack opposite the south gate and the fire seems to have started there and then spread into the outbuildings and the château. It was particularly unfortunate for some of the wounded, who had been put in the chapel to await casualty evacuation, when the straw on which they were lying caught fire, burning some of them to death. As it also burned the legs of the life-size wooden crucifix on the wall of the chapel,* it was obviously a serious conflagration, but was eventually brought under control.

The battle for Hougoumont went on all day, eventually drawing in Reille’s other two divisions, those of Major Generals Bachelu and Foy, and all to no avail, for the French never did capture the farm. Wellington said later that Hougoumont was the key to the Battle of Waterloo, but even if the French had captured it, that alone would not have allowed them to roll up Wellington’s right flank, for they would have been overlooked by the infantry and artillery on the ridge. Any attempt by the French to exploit the capture of Hougoumont by extending to their left would have run up against the troops in Braine-l’Alleud and Hill’s corps to the west and beyond. Perhaps what Wellington meant was that Hougoumont occupied one third of Napoleon’s infantry all day, infantry that might otherwise have been available to punch through the Anglo-Dutch centre later in the battle. What is extraordinary is the continuation of the battle for Hougoumont when it was obvious that Wellington was not going to – and did not need to – reinforce it by weakening his centre. Once that became apparent, Napoleon should have called off the attack on the farm, leaving perhaps a couple of battalions to occupy the garrison and prevent the farm being used as a jumping-off point for an attack on the French left. That Wellington had no intention of launching any such attacks was, of course, not known to the French.

The answer to why the French persisted at Hougoumont lies in a failure by Soult and his subordinate staff officers to get a grip of the battle and to know what was happening. From Napoleon’s observation post and tactical headquarters above and behind the Belle Alliance estaminet, it was almost certainly not possible to see Hougoumont,* but a proper system of command, control and communication should have kept the emperor informed of what was happening there. Such a system did not exist, or where it did exist did not function properly, and Reille, instead of querying the need to send more and more troops against an objective that was so well defended, just went on and on fighting a pointless battle. On a tactical level, it is hard to understand why on the initial assault by Bauduin’s brigade from the south a single cannon was not brought through the woods and used to blow in the gate. Even where the trees were too close together to permit the passage of a gun, pioneers could have cleared a route, and one or two round shot fired from the edge of the tree line at a range of twenty yards would have blown the wooden gate to matchwood; a few more could have demolished the orchard wall. Perhaps Bauduin thought that the capture of the farm would be a simple matter and did not want to wait for a gun.

Although the attack on Hougoumont had not caused Wellington to weaken his centre, the attack by French infantry on the Anglo-Dutch centre and left was to happen anyway. It began about half an hour or an hour after the beginning of the initial assault on Hougoumont and was entrusted to d’Erlon’s I Corps, supported on the left by the heavy cavalry of Brigadier General Dubois’ brigade of cuirassiers from the 13th Cavalry Division and on the right by Major General Jacquinot’s light cavalry. The objectives were the capture of La Haie Sainte and the smashing of Wellington’s left. The artillery of the Grand Battery would cover the advance by bombarding the ridge.

Sometime at around 1400 hours the French guns increased to rapid fire, shooting as fast as the gunners could load, fire, drag the guns back into position, sponge out, load and fire again. It was at this point that Grouchy’s men, still making a relatively stately progress towards Wavre and the Prussians, or where they thought the Prussians were, heard the increased tempo of the artillery fire, and once again there were doubts about what they should do. According to Captain Charles François, with Gérard’s corps, Grouchy’s infantry left Gembloux at about 1000 hours on the morning of 18 June and reached Walhain, five miles north, at 1300 hours, when they heard the increased cannonade from the direction of Mont-Saint-Jean on their left.* François, who was at the head of the column with the lead battalion of the 30th Line, says that Grouchy called a halt and seemed anxious, not knowing whether to cross the River Dyle or to march to the sound of the guns to support the emperor. According to François, Grouchy called a council of war (and as orderly officer of the day to Major General Pécheux, commanding the 12th Division of Gérard’s IV Corps, François would have been present) at which commanders were asked to consider the options of marching immediately to Mont-Saint-Jean to reinforce the emperor, or attacking Wavre. Gérard and II Cavalry Corps’ commander Exelmans were all for joining Napoleon at best speed, while Vandamme of III Corps thought that they should follow Napoleon’s orders to attack the Prussians. The various messages telling Grouchy to move over to Mont-Saint-Jean had not, of course, got through, thanks to faulty staff work and the sending of despatches by only one galloper. François describes Grouchy as saying that, while he agreed that the emperor was now engaged fully with the English (as the French always refer to the Anglo-Dutch army), were he to move to join Napoleon and Blücher then attacked him in flank, his army would be destroyed. The decision was to continue towards Wavre.35

On the field of Waterloo, d’Erlon’s infantry readied themselves for the advance on Wellington’s line. First they had to move through the gun line, which they did by battalions, moving in file led by their commanding officers. Given that no one could see very much through the banks of smoke and the various bits and pieces of artillery equipment to be negotiated, this would have taken some time. Once the troops were level with them, the guns stopped firing while the battalions, brigades and divisions sorted themselves out into their formations for the advance. Divisions were to attack in echelon from the left – that is, there would be a series of blows as successive divisions hit the Allied line one after another, beginning with Quiot’s 1st Infantry Division. As the troops on the left had farther to go than those on the right, Quiot’s men would be hitting the Allied line as the extreme right-hand French division, Durutte’s 4th, was leaving its start line. Divisions moved in column of divisions – that is, each battalion in line of three ranks, battalions behind each other with an interval of five yards between them. A company from each battalion was deployed forward as voltigeurs (skirmishers). An observer of a division of four regiments totalling eight battalions, each of 400 men (the light company being detached), would see a cloud of around 1,600 voltigeurs preceding a rectangle of men, 130 yards wide and 75 yards deep, containing around 3,000 soldiers and four eagles.* As maintaining this formation was critical for control, the advance could not be swift, probably no more than 50 yards a minute on rough ground.

Once the divisions were through the gun line and in their columns, they could start to move down the slope, drummer boys beating time and officers on horseback. When they were clear of the guns, the artillery could open up again, firing over the heads of the infantry. As with the initial bombardment, the effect was scrappy, and, although there undoubtedly were casualties to the Allied infantry lying down on the reverse slope, they were not significant. There is considerable disagreement among historians about the precise position of Bijlandt’s brigade at this point, the third brigade along from the crossroads included in Picton’s division. It is alleged that this brigade, unlike any of the others, was positioned on the forward slope and thus suffered heavily, before eventually running away. This is variously explained, ranging from Wellington having forgotten them to his deliberately placing them on the forward slope to draw the enemy’s fire, with all sorts of unlikely theories in between. This is, of course, nonsense: Wellington had an incredible eye for detail and would never have overlooked a whole brigade, far less deliberately exposed them to fire. The more prosaic truth is that, while they may have been on the forward slope early in the morning, bringing in their piquets and sentries, they would have been moved back, if not by Wellington, then by their divisional commander Perponcher or by the Dutch chief of staff Constant Rebecque. It is inconceivable that they could still have been forward when d’Erlon’s infantry began their advance, and reports that say otherwise are surely products of the tricks that memory can play later when the brain attempts to make some sense out of a whole series of confusing and traumatic events.

While Wellington’s infantry were lying down on the reverse slope out of sight of d’Erlon’s men and the gunners of the Grand Battery, the skirmishers and the Allied artillery were not. The technology to allow indirect fire – that is, firing at targets that the gunners could not see – did not exist, and would not for nearly a century, so the horse and foot artillery batteries were positioned on or just forward of the crest line. This did mean that they were vulnerable to French artillery fire, but it also allowed them to open up on d’Erlon’s approaching infantry. The best opportunity to do this came as the French battalions threaded their way through their own gun line and formed up in front of it, and lasted until the divisional columns had moved sufficiently down the slope to allow the Grand Battery to begin firing over their heads. The Allied guns, nine- and six-pounders, were firing at extreme range, and in the soft ground round shot hitting a divisional column would probably only kill two or three men. Shells fired from howitzers would be more effective, as would shrapnel, provided the fuse was cut correctly, but like the guns they were at their extreme range of 900 yards. Of course, once the French guns could recommence firing, the Allied artillery again became vulnerable. But as ever the soft ground meant that a round shot would actually have to score a direct hit to be effective, and the French guns too were at maximum range and would remain so, whereas the advancing French infantry were marching into the ideal beaten zone of the Allied artillery. From 400 yards or so, the Allied guns could switch to firing canister, a devastating weapon against close-packed infantry, and all guns and howitzers could continue firing until the French closed to within musket range (100 or 150 yards); then the crews would abandon their positions and scuttle off behind the infantry, usually taking a wheel with them to prevent the enemy taking the gun away.

Given that it would have taken the leading French division twenty minutes to get from the start line in front of the Grand Battery to within musket range of Wellington’s men, it might be wondered that, with the round shot, shell, shrapnel and canister aimed at them, they ever got there at all. But there were not, in fact, very many guns and howitzers on the Allied left – one British and two Hanoverian batteries of five guns and a howitzer each, and two Dutch-Belgian batteries of four guns each – and despite the target-rich environment presented to them, twenty-three guns and three howitzers were just not enough to stop, or even significantly slow down, the 18,000 or so approaching infantrymen. It was, though, not only the artillery that the French had to withstand as they tramped down into the valley and then began to move up the slope towards the Allies, but also the three companies of the 95th Rifles in and around the sand pit on the other side of the road from La Haie Sainte, and the King’s German Legion men in La Haie itself. Both these units, armed with Baker rifles, were able to snipe at the French long before the latter got within range to fire back. From the time the French reached the bottom of the valley onwards, the riflemen would have been picking off officers, porte-aigles (eagle-bearers), porte-fanions (flag-bearers) and drummers. But despite their sterling work, the mass of men came on, seemingly unstoppable, Marshal Ney and General d’Erlon on horseback in front of Marcognet’s 3rd Division. Once the French were within musket range, the 95th evacuated the sand pit and scurried back to the ridge – their job was to harry and snipe, not to exchange volleys at short range. The skirmish line of the light companies of the infantry battalions were able to cause some damage before they too retired, forming up as the rear company of their battalion in column, preparatory to becoming the left-hand company when in line. Most of the skirmishers’ musketry was directed against the French skirmish line, which also retired as their main body approached the crest.

The leading French division, that of Quiot, now split. The left-hand brigade of four battalions commanded by Colonel Claude Charlet moved to attack La Haie Sainte, supported by Dubois’ cuirassiers, while the second brigade, another four battalions under the command of Brigadier General Charles-François Bourgeois, carried on towards the ridge line. Aware of the risk to La Haie, Wellington sent a battalion from Major General Kilmannsegge’s 1st Hanoverian Brigade to reinforce the garrison, but it was scattered by the French cuirassiers and now the French infantry were through the orchard on the south side of the farm buildings and milling around the walls. The men of Bourgeois’ brigade and those of Donzelot’s division, behind and to the right of Bourgeois, could see the hedge in front of them but not much else, and Bourgeois and his men actually got to the hedge and began to force a way through it. So far, despite casualties during the advance, the advantage seemed to be with the French.

And then the balance began to shift. Lieutenant General Picton was ordering his men to stand up and move forward, and the forward battalions of the brigades of Kempt – next to the crossroads – and Pack came from column into a two-deep line, each covering a frontage of around 400 yards. In between was Bijlandt’s brigade, covering perhaps 200 yards. It was Donzelot’s leading battalion who hit the hedge, crossed it and advanced on the Dutch-Belgians, who fired one or possibly two volleys and then, with the exception of a Dutch battalion that stood its ground, began to fall back, despite the urgings of most of their officers. To be fair, they had been heavily pounded at Quatre Bras, many were recent veterans of the French army, many were raw recruits, and as for the rest, their hearts just weren’t in it. That said, their withdrawal of labour did create a dangerous gap in the Allied line, which Donzelot was only prevented from capitalizing on by the British battalions to left and right of the gap, the 1/28th and 3/1st Foot, beginning to fire what Wellington called ‘clockwork volleys’ of coordinated musketry. This stopped Donzelot for a time, while further to the west Bourgeois had halted his brigade to change formation from column into line. He was thus caught in midmanoeuvre by the 32nd and the 79th, whose volleys at a range of fifty yards could hardly miss. It was probably about this time that Picton’s premonition was fulfilled. Mounted on his hairy-heeled cob, wearing a stovepipe hat and armed with an umbrella, he was cheering on his men when he was hit in the head by a musket ball and fell to the ground dead. His body was carried to the rear.* Meanwhile, with the action on the Allied centre left now in full swing, the infantry on the right centre, realizing the threat from Dubois’ 700 cuirassiers, moved into square.

The fighting around La Haie Sainte was fierce. Baring’s men, assisted by the 95th Rifles, had built a road block across the Brussels road and had loopholed the roof and the walls, but while the cuirassiers were in the area, sending infantry reinforcements down was not a sensible option. Nevertheless, the French advance had been stopped and thrown into some confusion: now it was time for them to be thrown back. Major General Lord Edward Somerset, commanding the Household Brigade stationed behind the infantry to the west of the Brussels road, had posted one subaltern from each of his four regiments on the crest, to keep him informed of what was going on. Somerset, born in 1776, the fourth surviving son of the fifth duke of Beaufort, had become a cornet in 1793 aged seventeen and progressed rapidly through the ranks, becoming a lieutenant colonel in 1800 at the earliest possible time after the regulation seven years’ service. He served in the Peninsula, being present at all the major battles from Talavera in 1809 to the end of the war at Toulouse in 1814 as a lieutenant colonel, a colonel and, from 1813, a major general commanding a cavalry brigade. An experienced and highly competent officer, for most of the morning Somerset had his men dismounted with girths slackened, but now, knowing what was happening on the other side of the ridge, he had the 1,200 men of his brigade mounted and formed in two lines ready to go.

On the other side of the road, Major General Sir William Ponsonby could see what was happening to his front and he too ordered his men to tighten girths and surcingles and to mount up. Ponsonby, who was forty-three at Waterloo, had had a more chequered career than his fellow heavy cavalry brigade commander. He was commissioned as an ensign in 1793 and had moved through three different infantry regiments as a lieutenant and captain, followed by a stint as a major in the Irish Fencibles, before transferring to the cavalry as a lieutenant colonel in 1800. He too served in the Peninsula, where he had initially commanded his regiment in Le Marchant’s heavy cavalry brigade, before taking over the brigade after Le Marchant’s death at the Battle of Salamanca in 1812 and, as a major general from 1813, commanding it until the end of the war.

There is dispute over who ordered the British heavy cavalry to charge. Lord Uxbridge insisted it was done entirely on his initiative, without any prompting from Wellington. Although Wellington had given Uxbridge overall command of the cavalry, the duke did not by nature delegate, and it seems unlikely that such a critical decision was left to others. Who gave the order is immaterial: the point is that the two heavy cavalry brigades were ordered to charge to take advantage of the – probably temporary – disorganized state of the French infantry.

To the west the Household Brigade moved through the gaps in the infantry squares, negotiated the sunken road around the crossroads, and charged the French cuirassiers. ‘Charge’ is hardly the most apt word as it was delivered at a trot, the ground being heavy and the distance short, but the brigade’s 1,200 men hit the French’s 700, and after a short scrap in which the British advantage of the high ground was countered by the protection of the French cuirasses (British heavy cavalry did not wear armour) and which involved much clanging of sword against sword and sword against armour, numbers told and the French were seen off.* Without cavalry support, the infantry of Charlet’s brigade around La Haie were desperately exposed and Somerset’s men swept through them, scattering them and cutting down those who could not find cover or run fast enough. They then swung left across the road and into the flanks of Bourgeois’ brigade. To the east of the Brussels road, the British infantry closed up to allow the Union Brigade to pass through and force the hedge, and with the brigade commander in the lead, they too hit the French of Donzelot’s division, which was already in some confusion caused by the infantry volleys.

With no time to form square to receive cavalry and under fire from the British infantry to their front, d’Erlon’s attack dissolved into a desperate attempt by scattered individuals to avoid the slashing heavy straight swords of the cavalry who now had their blood up. The best protection for a soldier who could not evade a cavalryman coming at him was to lie down – a trooper armed with a sword could not reach a man lying on the ground and would go off in search of an easier target.* It took a brave and confident soldier to take that course, however, and most simply ran. Against a pursuing cavalryman the running soldier was reasonably well protected. His shako protected his head, the thick high collar of his tunic his neck, his epaulettes his shoulders and his haversack his back,† so the experienced cavalryman did not waste time and effort in slashing at the fleeing infantryman from behind, rather he overtook him and backhanded his sword, hitting the unprotected face and splitting the man’s head.

Once the British heavy cavalry were into the French infantry, the carnage was considerable: their heavy sword was not particularly well balanced, but it was long – and heavy – and it created fearful wounds. There was no question of the French infantry standing, and as individuals or as small groups in companies and half-companies they fled back whence they came. Had the cavalry now rallied and held hard, they would have rendered a significant service. While not all of d’Erlon’s men had been scattered – Durutte’s division had only just left their start line and were untouched, and much of Marcognet’s division were able to withdraw in good order – they had nevertheless received a bloody nose; La Haie had been saved and the Allied centre left flank was intact. Unfortunately, the British cavalry rather tended to be a ‘fire and forget’ weapon, delivering a magnificent charge and then disappearing over the horizon in search of loot or glory or both and not returning until the battle was over. On this occasion, despite the efforts of the two brigade commanders to curb their enthusiasm, and the trumpeters blowing the recall over and over again, most took absolutely no notice and pursued the French infantry down the hill, and when they had overtaken them, they spotted the French Grand Battery and decided to charge that too. One soldier reported afterwards that he was passed by an officer with sword in the air shouting, ‘On to Paris!’ In the Union Brigade, the Royal North British Dragoons, or Scots Greys,* who were ordered to form the second line, refused to be left out of the fun and moved up to be level with the leading squadrons, capturing the eagle of the 45th Line of Marcognet’s division. Most did in fact reach the gun line and were having a jolly time whacking the gunners when the inevitable reprisal struck. Napoleon saw what was happening and ordered a counter-attack by two regiments of lancers and one of hussars from Jacquinot’s light cavalry, on the French extreme right flank, and four regiments of cuirassiers from Milhaud’s reserve cavalry corps, stationed behind the French centre right.

The French had first come across the lance when experiencing it in the hands of Polish and Russian soldiers, and while there were Polish lancers in the French army (chiefly in the Imperial Guard), most lancer regiments were now composed of Frenchmen, albeit dressed in the Polish manner. The lance was nine feet long with a steel spike and a wooden shaft, and as it could only be effective in a charge when held by men in the front rank, only about one third of soldiers in lancer regiments actually had a lance, the others having carbines and light cavalry sabres. Although the sight of a line of galloping lancers, lances couched and levelled and pennants fluttering in the wind, would indeed have been terrifying to the inexperienced, they were not as fearsome as they looked. If a defending cavalryman could evade the first thrust and get inside the point, then all the lancer had to parry the other’s sabre was the unwieldy wooden shaft; and while a lancer could of course reach an infantryman lying on the ground, he had to come to a halt or at least a walk before spearing him, as to do so at the canter or gallop would propel the lancer off his horse. Similarly, if a lancer did manage to skewer an opposing horseman, it required considerable skill to extract the lance and remain mounted.

Lancers were trained to couch the lance under the arm but in practice the best way to use it was to hold it by the point of balance and allow the momentum to do the damage, the rider then twisting his body and head round while extracting the lance. Failure to ‘follow the point’ meant that the butt of the lance would hit the lancer on the back of the head, putting him on the deck.* Against an infantryman standing up, the lancer had a longer reach than the musket and bayonet but, as when cavalry were attacked by lancers, if the infantryman could evade the first thrust, he could bayonet the lancer or his horse. Against fleeing cavalry on less fit horses, however, the lance was deadly, and in this case the lancers were able to come up behind the British on their already exhausted horses and poke their lance points into their opponents’ backs.

Attacked by 2,500 fresh French horsemen, the British cavalry, disorganized and with horses blown, had no alternative but to try to return to their own lines as fast as they could. Unfortunately, that was not very fast. In their flight back whence they had come, one brigade commander, Ponsonby, was killed; the other, Somerset, escaped unscathed, but his brigade major, Smith, was killed, as were three of the seven commanding officers of regiments, while two others were wounded. Had Ponsonby been mounted on his main charger, he might well have survived, but precisely at the wrong moment its groom had taken it for a walk and Ponsonby had to charge on the inferior hack that he had been riding during the morning. Coming back up the hill in the mud, he had no chance against a lancer. Altogether, only about half the men of the two brigades returned with their horses and capable of duty. The others were taken prisoner, wounded, dead or without their horses, and there is nothing more useless than a heavy cavalryman without his horse, or a heavy cavalry horse without its rider.

It was while all this was happening that Grouchy launched his attack at Wavre. Vandamme hurled the infantry of his III Corps at the bridges defended by Thielemann’s Prussians, but this was a totally pointless operation, which contributed not a jot to Napoleon’s strategic situation, for it had no effect whatsoever on the activities of the three Prussian corps on their way to Waterloo. Captain François says the attack on Wavre began at about three o’clock, and it was at around this time that, despite the problems of moving large number of troops across difficult country, the advance guard of Prussian infantry and cavalry was in the Bois de Paris and throwing out a skirmish line to ensure that they were not interfered with by the French cavalry on the emperor’s right wing. But those cavalrymen were far too interested in what was going on to their front to notice what was happening in the woods, and it was probably the sight of Prussian troops on the heights of Chapelle Saint-Lambert, about four miles away to the north-east, that alerted Napoleon to the imminent arrival of the Prussians. From the emperor’s point of view this was serious, but not critical – he could still defeat the English and their lackeys long before the Prussians could possibly intervene.

* The 3rd Foot Guards thought it was a Private Joseph Brewer and later allowed him to transfer to their regiment, but sources are vague.

† They were not highly thought of, somewhat unfairly, and by Waterloo had scarlet tunics rather than blue.

* Commanders and their ADCs carried prepared strips on which messages could be written and then rubbed out by the recipient so that a reply could be written.

† One of the very few messages that survive, this one is in the British Museum.

* The crucifix was stolen, probably to order, in 2011. There are some very sick people about.

* An intersection diagram on a modern map shows that, if contours remained unchanged and trees were removed, it would be just possible, but on the day it would have been unlikely, even without the clouds of black smoke.

* It was probably nearer 1400 hours, but, as explained, timings in contemporary accounts vary widely.

* Some regiments had three battalions, occasionally four, and battalion strengths varied, but the principle is the same, with only the senior battalion of the regiment, the 1st, having the eagle.

* Some accounts claim that the bearers were two Highland grenadiers of the Black Watch, the 42nd, who stole the general’s gold-rimmed spectacles. This has to be a disgraceful calumny on a fine regiment, for the 42nd were in Pack’s brigade, a good 500 yards away, and if any Highlanders did steal the spectacles, they could only have been from the 79th, the Cameron Highlanders, who were in Kempt’s brigade and only a few yards from where Picton fell.

* The Household Cavalry were equipped with armour shortly after Waterloo, along with a helmet copied from the French. It is that uniform that is worn by the Household Cavalry on ceremonial occasions today.

* This statement has been disputed: one otherwise thoroughly reliable historian has said that, as a sword is the same length as a polo mallet, with which it is possible to hit a ball running along the ground, then stabbing a prone man would be no problem. It would appear that the writer has never ridden a horse, handled a sword or played polo. From personal experiment, using dummies, this author has found that it is possible to reach a man lying down with one’s sword if one is fit and supple, but not when the horse is carrying all the impedimenta issued to the cavalryman. Strapped to various parts of the saddle, among other bits and pieces, were piquet ropes and pegs, a spare set of horseshoes, a hay net (full, if possible), rations for the soldier and the horse, the soldier’s haversack with his personal kit, and the issue carbine in its leather bucket plus ammunition for it. All of this restricted the rider’s movement considerably, and leaning over and stretching down far enough to stab a prone opponent would not have been possible.

† Today we would drop our large packs before attacking; then to do so meant that they would be stolen – if not by the enemy, then by your own, albeit from a different regiment. The soldier carried all he had with him as the only sure way of retaining his meagre possessions.

* So called because they rode grey horses, and continued to do so. In the First World War their horses were dyed brown or black with vegetable dye to make them less conspicuous. In 1815 camouflage was not a consideration. The well-known painting Scotland Forever by Lady Butler (née Thompson) was done in 1886 when her husband commanded at Aldershot. A trench was dug for her to sit in with her easel while a regiment of cavalry galloped past her. A wonderful painting, certainly, but it is a lot more glorious-looking than the real thing.

* As this author discovered the first time he tried tent-pegging.