THE DECISION

By around 1530 hours, it was obvious to Napoleon that the Prussians were appearing off to his right and that, despite increasingly urgent summonses, which never got though, Grouchy was nowhere to be seen. For the ordinary soldier who might have peered through the smoke over his right shoulder, Prussian black was not easy to distinguish from French blue at a range of almost two miles, and any who had the temerity to ask were told that the troops in the far distance were those of Grouchy, come to reinforce. As Reille’s infantry was still wholly occupied by Hougoumont farm and that of d’Erlon was still recovering from its repulse by Picton’s division and the British heavy cavalry – a recovery that they managed remarkably quickly, despite the casualties incurred – the only French infantry so far uncommitted were those of Lobau’s VI Corps, stationed on either side of the Brussels road south of La Belle Alliance, and the Imperial Guard, further back still. Unwilling to deploy the Guard until absolutely necessary, Napoleon ordered ‘Mr Sheep’, as Lobau was unofficially known,* to deal with the Prussian approach.

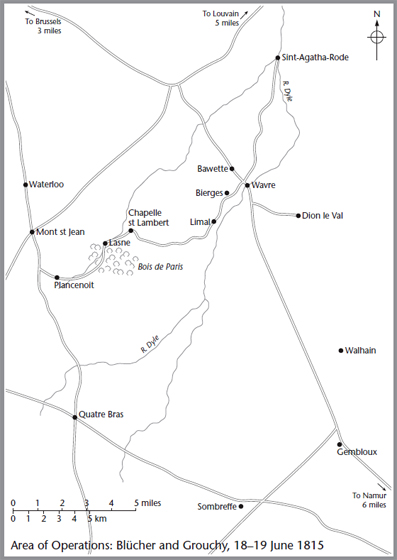

One of the kinder plays on Lobau’s name was made by Napoleon, who on one occasion remarked, ‘Mon mouton est un lion.’ In this campaign, however, Lobau was anything but lion-like. He had been slow and cautious during the advance to the River Sambre on 15 June and now, instead of advancing into the Bois de Paris, where so far there was only Prussian cavalry and vanguard infantry with a thin skirmish line, he deployed his two infantry divisions, Simmer’s 19th and Jeanin’s 20th, in a static blocking position between the village of Plancenoit and the edge of the Bois. Had Lobau been a little more adventurous, he would have used his two cavalry divisions, those of Domon and Subervie, to sweep the late Colonel von Schwerin’s hussars and uhlans out of the way (Lobau had over 3,000 men against 1,200) and drive into the Bois, where he could have caught Bülow on the line of march and pushed him back, perhaps as far as the valley of the River Lasne, a tributary of the Dyle. In any event, he might have bought valuable time, but as it was his deployment did nothing to prevent the Prussian build-up in and in front of the Bois de Paris.

Elsewhere on the battlefield, skirmishing between Saxe-Weimar’s troops in and around Papelotte farm and Durutte’s division on the Allied right flank continued. Durutte had been virtually unscathed during the repulse of d’Erlon’s corps, but Saxe-Weimar conducted a skilful defence, abandoning outlying farms and hamlets when there was no point in hanging on to them, but preserving his position in Papelotte itself, supported by the two brigades of Allied cavalry to his rear. At Hougoumont the battle went on, with Allied reinforcements moving down from the crest when required and back up again when not, while attacks by elements of d’Erlon’s corps against La Haie Sainte were almost continuous, so far without success.

It was around mid-afternoon that Napoleon is said to have felt ill and went to recover in the farm of Rosomme, just behind his tactical observation post and where the Victor Hugo memorial is now. Clearly, it would not have done for the troops to see the emperor in a state of discomfort, although there is some doubt about what was so wrong that he had to go and lie down. True, he was short of sleep and had covered many miles of rough roads in badly sprung vehicles or in the saddle, and as he knew full well that this was his last chance to recover his former eminence, the mental stress would have been considerable. Still, he was only forty-six, the same age as the Duke of Wellington, and while he had not taken the same care of his body as his adversary had, he should nevertheless have been able to withstand the strain. One authority, after an exhaustive examination of post-mortem reports, has suggested that Napoleon suffered from gonorrhoea and syphilis, and symptoms of the latter include lightning pains and temporary loss of balance. One account says that Napoleon slipped on the muddy ground and had to be helped up, but a momentary loss of balance could have happened to anyone, regardless of his state of health. Whatever the cause of Napoleon’s temporary incapacity, it left Marshal Ney, nominal commander of the left wing of the army at Waterloo, without the supervision of his emperor, which would lead to yet another misreading of the situation, with serious consequences.

It is perhaps apposite at this point of the battle to compare the command styles of the two main protagonists. Wellington is constantly moving about the battlefield, personally checking that his orders are being carried out, seeing and being seen by his subordinate commanders and, perhaps even more important, by the non-British elements of his troops. He is alert, aware of what is happening in every corner of the field, full of energy in directing the defence: completely on top of his task and seen to be so. Napoleon, on the other hand, seems content to let the battle run its course without intervention from him. He makes little effort to find out what is happening, those orders that he does issue are unclear, and except when he goes to the rear to rest, he remains at his command post, unable to influence the course of the day by his presence. Whether his lethargy was physical, mental or a combination of both, he is an old man, overweight, unfit and seemingly unable to muster that tactical acumen that won him a score of battles and conquered the whole of Europe. The old magic that inspired thousands of men to march willingly to their deaths for him has somehow gone.

As it was, although d’Erlon’s attack had been repelled, it had not been without cost to the Allies, and, although their artillery had been far less effective than the French had hoped, it too had caused casualties. Although the infantry on the reverse slope of the ridge occupied by Wellington were out of his view, Ney could see horse-drawn vehicles on the ridge itself and the tops of regimental colours moving away, and, excitable fellow that he was, he assumed that this was the Allies retreating. In fact, what he was observing were wheeled ambulances taking wounded back to the main field hospital, ammunition carts going back to be replenished, and columns of prisoners and colours going to the rear.

A British battalion had two colours:* the king’s colour, which was the union flag with a crown and the regimental number in the middle, surrounded by the ‘union wreath’, a wreath of shamrocks, roses and thistles; and the regimental colour, which consisted of the regimental facing colour (blue, buff, green, black, white, grey or yellow) with the union flag in the top left-hand corner. Each colour was six feet square and made of heavy, double-sided silk and was carried on a pole ten feet long. Originally intended as a rallying point in battle, as the years went by, the colours acquired a mystical significance, representing the spirit of the regiment, and were even consecrated before presentation to the battalion. It was regarded as a frightful disgrace to have one’s colours captured,† and in this case commanding officers, sensing that things were going to hot up, had very sensibly told their colour parties to get out of the danger area.‡

Having convinced himself that the Allied right was retiring, Ney sent an ADC to the nearest cavalry brigade, that of Brigadier General Pierre Joseph Farine du Creux, who was forty-five, had enlisted as a volunteer in 1791 and had been elected lieutenant three years later. Coming to a halt in front of Farine, the ADC shouted that Marshal Ney wished him to advance his two regiments of cuirassiers and seize the plateau – that is, the ridge on the Allied right. Farine was reluctant – he had fought the British in Spain and been captured and sent to England as a prisoner of war, from where he had escaped back to France – but faced with orders coming from a marshal of France, he began to move his squadrons forward. Farine’s divisional commander, Major General Jacques Antoine Adrien Delort, who was forty-three and whose military career had begun when he enlisted as a national guardsman in 1789, saw what was happening, spurred his horse forward and told Farine to stand still. To protests from Ney’s ADC, Delort pointed out that Farine took orders only from his divisional commander – him – and that he took orders only from his corps commander, the 39-year-old Major General Édouard Jean-Baptiste Milhaud. A hard-bitten cynic, Milhaud was not one to blindly obey the orders of Ney, even if he was a marshal, particularly when those orders were delivered second-hand and to one of his subordinates rather than through him.

Ney himself, increasingly agitated at the lack of action despite his orders transmitted through an ADC, now appeared and ordered Milhaud to take the whole corps, not just Farine’s brigade, and capture the ridge from which the English were retiring. Milhaud demurred: attacking British troops head-on when they were on a position of their choosing and making use of a reverse slope was unwise; time and again in the Peninsula such an approach had failed, and it could well fail here. Ney, despite his own experiences in Spain, would have none of it, and Milhaud, finally and reluctantly, accepted that he had no alternative but to do as he was told.* The two divisions of IV Reserve Cavalry Corps began to move forward down the hill to form up in the valley. The corps consisted of four regiments of cuirassiers, three with four squadrons and one of three, a total of around 3,000 horsemen, allowing for the casualties incurred by Watier’s division in supporting d’Erlon’s attack. Behind Milhaud’s regiments was the light cavalry division of the Imperial Guard, commanded by Major General Lefebvre-Desnouettes, late resident of Cheltenham and breaker of parole. Unable to resist the opportunity to take part, Lefebvre, without orders, followed with his division of the Chasseurs à Cheval and the ‘Red Lancers’,† each of five squadrons, or around 2,500 officers and men altogether.

The valley where the cavalry would form up prior to advancing and through which the attack would take place was the gap between Hougoumont farm and La Haie Sainte, a distance of 900 yards. Although both those locations were under attack and would continue to be so, allowing for leaving a musket shot’s distance from each, the cavalry had a frontage of around 700 yards available to them, although this would widen out once past those two farms. This would give a frontage of just over 100 yards for each of the seven regiments. A horseman needs an absolute minimum of a yard of space, and, although squadron sizes varied from sixty-five men in the 6th Cuirassiers to 230 in the Chasseurs à Cheval of the Imperial Guard, the frontage would only allow regiments to form up in double column of squadrons, each squadron in two ranks. A typical regiment such as the 1st Cuirassiers would have its first and second squadrons abreast, in two ranks, in the first line, and its third and fourth squadrons, also abreast and in two ranks, in the second line. The regiment’s frontage would be 120 yards. The Chasseurs à Cheval, by contrast, drawn up in the same formation but with its fifth squadron forming a third line, would cover 230 yards. The point is that there was not very much room to get 5,500 men lined up to deliver what Ney hoped would be the blow to win the battle. Indeed, some French sources claim that the men were packed so tightly together that, when they moved off, some horses and men were lifted into the air by the press of those on either side – ridiculous, of course, but it makes the point.

To a young Allied soldier looking at the flower of the French cavalry forming their regiments and squadrons in the valley 400 yards below him, the sight would have been both magnificent and terrifying. The polished, albeit by now mud-spattered, cuirasses and helmets flashing in the sun, the lance points glistening, the guidons and pennants fluttering in the slight breeze, the gorgeously caparisoned officers in front lining up their men – all gave the impression of an unstoppable juggernaut that only had to charge up the hill to put all in its path to flight. Only a few Allied soldiers could see all this, however: skirmishers of the infantry light companies, those defenders of Hougoumont and La Haie Sainte who were not otherwise engaged, and the gunners on the ridge. To the gunners, it must have seemed that all their Christmases and birthdays had come at once, for, although the French Grand Battery bombarded the Allied gun line over the heads of the cavalrymen, it took a very accurate (and lucky) shot to do any damage to the Allied guns at a range of nearly a mile, whereas these latter were firing at a distance of only 400 yards or so. Wellington had always considered his right flank to be the one most at risk and had concentrated his artillery there. There were eleven British and German batteries on the right flank, and with one battery covering La Haie Sainte, there were ten batteries, or sixty six-pounder and nine-pounder guns and howitzers, to take on the cavalry. And take them on they did.

Once the French cavalry regiments were lined up in their regimental columns, Marshal Ney took post in the front centre and the order was given to draw swords. Thousands of blades glinted in the sun and the whole mass moved forward. Tactical advice for a ‘normal’ cavalry charge dictated that the men should walk their horses for the first quarter-mile, trot for the second, canter for the third and gallop for the last quarter-mile. There is, however, rarely any such thing as a ‘normal’ situation in battle, and this one was far from normal: the heavy going (and the bottom of the valley was little better than a bog) and the still untrampled rye restricted the horses to little more than a walk, escalating into a slow trot as they moved up the slope. A horse trots at about eight miles per hour on level ground but in these conditions would hardly manage six, so would take two minutes to reach the crest, giving the Allied artillery time to get off three or four rounds per gun. At that range round shot would plough through the column, taking out as many as four troopers before hitting the ground and sinking in the mud; canister would do even more damage, as would common shell and shrapnel. Even allowing for the degradation caused by firing downhill, the artillery would have caused considerable damage to the French cavalry well before they reached the crest. Once the cavalry reached within carbine shot of the guns, the gunners withdrew, leaving their guns where they were and retiring to the protection of the infantry behind them, as usual taking a gun wheel with them.*

The Allied infantry had ample warning of what was to come: although the men and the junior officers could not see over the crest, the senior, mounted, officers could and the battalions were ordered to form square, a process that from column took about a minute. In a ten-company battalion a square was actually an oblong, with men packed shoulder to shoulder in four ranks. The long sides of the oblong each had six half-companies, while the short sides each had two companies. The light company which would be out in front in the skirmish line – and horribly vulnerable to cavalry – was the last company to come in when the battalion formed square and was the outer two ranks for one of the short sides. Whether a short or a long side faced the cavalry threat depended on the ground, the position of other battalions, and the formation that the battalion was in prior to the order ‘Prepare to receive cavalry’. At Waterloo some battalions presented a short side to the French cavalry, others a long side. In a battalion that was up to strength, the short sides would be twenty-seven yards in length (two feet per man) and the long sides eighty yards. The front rank knelt, with muskets at an angle of forty-five degrees, the butts on the ground and bayonets fixed. This front rank did not normally fire, except in dire emergency; rather, their task was to present an impenetrable hedge of bayonets. The firing was done by the second and third ranks, with the fourth filling gaps in the other three caused by men killed or wounded. The short sides would fire by rank, meaning a pause of fifteen seconds between each volley, or by file, while the longer sides would fire by half-companies with an interval of ten seconds. In the centre of the square would be the commanding officer, the adjutant, the sergeant major, the colour party if not already despatched rearwards, the drummers, gunners from the nearest gun, and a few spare men as stretcher-bearers to pull the wounded or the dead into the centre and out of the way. Company officers and NCOs were behind their companies, company commanders remaining mounted so that they could see over the heads of their men in front.

The skill required of the company officers and NCOs commanding half-companies was in knowing when to give the order to open fire. Firing at too great a distance was ineffective, whereas waiting for the cavalry to get too close meant that a dead or dying horse might crash into the square, creating a gap through which other cavalrymen could enter. If that happened, as it did on one occasion in 1812 to a French square at Garcia Hernandez in Spain, then the square was doomed. Experienced officers and sergeants – and most of the British officers and sergeants were experienced – would give the order to fire when the cavalry were thirty yards away, and men were told to fire low so as to hit the larger target of the horse rather than the smaller one of the rider.

By the time the cavalry breasted the hill, the gunners had retreated to the squares and the skirmishers had rejoined their battalions. As the French rode through the Allied gun line, they were faced with twenty-seven battalion squares to the west of the Brussels road, and the 1/27th just to the east of the crossroads but also in square. The squares were laid out like pieces on a draughts board, in a chequered fashion, so that the soldiers could fire without hitting their neighbours. The French, still only at a trot, came on, and at a distance of thirty yards the faces of the squares began to belch flame and smoke. At that range the carnage among the horses was considerable. Down they went, dead, dying or badly wounded, creating an obstacle to be negotiated by those behind. No horse will charge at something that it cannot jump over,* and, however the riders may have dug in their spurs, the horses would not approach the line of bayonets. Instead, they swerved off left and right, with their impotent riders able to do little but ride round and round the squares waving their swords. Even the lancers could achieve little, and while the riders in some cavalry squadrons, their horses refusing to go forward, discharged their carbines at the infantry, this did little damage, as apart from the inherent inaccuracy of the short-barrelled smooth-bore carbine, firing from a moving horse was very much a hit-and-miss business – mainly miss. Horses wounded but not brought down were quite likely either to dump their rider or to whip round and try to get back whence they came, causing confusion and adding to the difficulties of movement for the remainder. The heavy ground did at least prevent the horses from bolting – galloping off out of control. The types of bit in use in 1815 with their very long curbs would stop a charging elephant, although if fitted today – along with the razor-sharp spurs then in common use – they would spark instant prosecution by the RSPCA.*

The private soldier standing or kneeling in square would have seen little after the first volley was fired. After that he could only listen to the commands of his officer or sergeant as he reloaded his musket and waited for the command to fire into the smoke. Packed shoulder to shoulder and unable to move except to handle his weapon, he would have to urinate and defecate where he stood. The inside of a square was not a pleasant place to be: the horrific noise of screaming horses, the firing of one’s own and one’s comrades’ weapons, the rotten-egg smell of discharged gunpowder, the moans of the wounded dragged into the centre of the square, the bellowing of the sergeants – all just had to be endured. Many of the British soldiers had done it all before, and for those who had not there were plenty of old campaigners to reassure them that as long as they stood, as long as they followed the drill movements that had been hammered into them in training, as long as they fired low, then nothing could harm them. The desperate thirst brought on by the saltpetre content of the bitten cartridge, the bruised and painful shoulder caused by the mule-like kick of the musket, the skinned knuckles caused by ramming down if bayonets were still fixed: all could be ignored and overcome as long as the mechanical movements of loading, firing and reloading were followed. For soldiers in some of the foreign contingents who had never experienced the excitement and the terror of standing still with huge horses coming at them, the temptation to break and run must have been almost overwhelming, and it says much for the faith that their officers had in Wellington that the men kept to their duties and did not quit the field.

All nations’ tactical manuals recognized that steady infantry in square were completely impervious to the actions of cavalry. The way for cavalry to deal with infantry was to charge at them to force them to form square, and then to peel off, allowing the horse artillery that should be following close up to tear great holes in the square – holes that could then be exploited by the infantry that should also be following close up. What Ney should have done, therefore, was to ensure that the cavalry divisional commanders had their attached batteries of horse artillery close behind them and to send infantry behind the artillery. Artillery did go forward with the cavalry, but the operation was mishandled: in some cases a division’s own battery had been taken away to form part of the Grand Battery, and so that division had either to take a battery not known to its officers or to go without. In any event, instead of the cavalry peeling off once the first assault had obviously failed, and thus allowing the artillery a clear field of fire, they continued to ride round and between the squares, preventing their own artillery that did get to the ridge from being able to fire. On the rare occasions when the French horse artillery did get a chance to open fire, they did do considerable damage. One of the 1st Foot Guards squares had a gap torn in its side, and had the commanding officer not reacted swiftly by pushing rear-rank men into it, the hovering lancers, waiting for just such an opportunity, would have been in.36

The French cavalry who did manage to pass between the squares without injury were counter-attacked by the Allied cavalry in rear. The remnants of the Household and Union heavy cavalry brigades – along with the British and KGL light cavalry of Generals Grant, Dornberg and Arenschildt, as well as that of de Collaert’s Dutch-Belgians – seemed to have learned the lesson of pursuing too far: instead, they made short, controlled charges to stop the now disordered attackers advancing any further. Only one of the Allied cavalry regiments failed to do its duty, and that was the Duke of Cumberland’s Hussars, an essentially amateur regiment of wealthy Hanoverian gentlemen who provided their own horses and equipment. Ordered forward to take on French cavalry by Dornberg, they would not budge, broke and began to filter to the rear. Despite appeals from both Dornberg and Arenschildt, the Cumberlands’ commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Georg von Hake, refused to rally his men, who made off as fast as their expensive mounts would carry them in the direction of Brussels, where they spread a certain amount of alarm and despondency by assuring all who would listen that the battle was lost. Hake was later removed from command and brought before a court martial in Hanover, which ordered him to be reduced to the ranks and cashiered, while his second-in-command, Major Mellzing, was severely reprimanded for failing to prevent the defection of the regiment.

As for Ney, not only did the marshal fail to coordinate the movement of the cavalry and artillery, but he also failed to support them with any infantry. Most seriously of all, at no stage did the French cavalry attempt to spike the Allied guns. A spike was essentially a six-inch nail that was driven into the touch-hole of a gun, rendering it useless. If a spike was well hammered home, it could not be removed in the field and the gun had to be taken back to workshops to have the metal around the touch-hole drilled out and a cone of metal with a new touch-hole inserted from inside the barrel. Cavalrymen usually carried spikes and mallets for this very purpose, but either the French had not issued them or in the heat of the action their cavalry neglected to use them. Either way, the failure to spike the guns when there was ample opportunity to do so exposed the cavalry to even more death and destruction, for each time the regiments pulled back to re-form and charge again, the Allied gunners ran out and gave them one or two more rounds. How many times the French cavalrymen pulled back and came on again is disputed, but what is not is that each time they retired, the Grand Battery was able to reopen its bombardment of the Allied gun line. And yet despite the ever more frantic urgings of their officers – who all Allied accounts say were extraordinarily brave – to urge them on, Milhaud and Lefebvre’s men could make no headway, and Ney, reinforcing failure, next added Kellermann’s III Reserve Cavalry Corps to the mix. Another eight regiments of heavy cavalry – two of dragoons, four of cuirassiers and two of carabiniers (cavalry men who carried a rather better carbine than the rest of the cavalry), about 3,500 men in all – plunged down the hill into the valley and up the slope towards the ridge. Kellermann, sensibly, had told the commander of the carabiniers to stay back near Hougoumont as a reserve, but Ney would have none of it and so the carabiniers too joined the rush. The marshal had already had several horses killed under him and was rapidly running through his stable of chargers; he was also dashing about excitedly and ignoring the chain of command by barking orders directly to regimental and even squadron commanders. It was no way to direct a battle.

Around 9,000 men in total were now committed to no avail – virtually all of the French cavalry, save the heavy cavalry of the Imperial Guard, two divisions with Lobau over at the Bois de Paris and Piré’s division of two regiments of lancers and two of chasseurs à cheval attached to Reille’s corps, which hovered on Wellington’s extreme right flank but took no part in this action. While there were significant Allied casualties, mainly from the French horse artillery, not a single square broke. When some battalions had taken so many casualties that they could not sustain a square of their own, they amalgamated with another battalion to form a square with it, while in contrast the 52nd Light Infantry formed two squares. Napoleon, returning from Rosomme, was aghast: how could cavalry be sent against infantry without supporting infantry of its own? By the time some infantry had been found to send forward, it was too late. The French cavalry, that magnificent instrument, was broken, and the trampled ground in front of and around the infantry squares was littered with dead and dying horses, with dead and dismounted cavalrymen, the latter being rounded up and sent to the rear as prisoners.

By now it was around five o’clock in the afternoon, and over in the Bois de Paris Bülow had two brigades (effectively divisions) present, those of 53-year-old Major General Michael Heinrich von Losthin and 43-year-old Colonel Johann August Friedrich Hiller von Gartringen. Each brigade had nine battalions of infantry, an attached cavalry squadron and a field artillery battery. Also present were the two regiments of the late Colonel Schwerin’s cavalry. Still to come were two brigades of infantry, two cavalry brigades and the artillery reserve. Bülow had originally intended to wait for the rest of his corps to arrive before moving against the French, but seeing the mass cavalry charges through his telescope and realizing the precarious situation that Wellington was in – and despite the carnage handed out to the French cavalry, Wellington’s situation was, if not perilous, then at least dangerous, with more and more of his reserves being moved forward – he decided to move with what he had got. Two battalions were sent off to link up with Saxe-Weimar and reinforce his position around Papelotte, while the remainder, preceded by a cavalry screen, moved out of the woods and started to advance on the village of Plancenoit, whose church spire could be seen and was an obvious point of reference.

Plancenoit, behind the French right flank, was one of those villages built for defence during the wars of religion, with stout, thick-walled buildings clustered around the church. Napoleon, ever the optimist, had not ordered it to be prepared for defence, but it would nevertheless be a veritable fortress and a tough nut to crack if properly manned. Bülow’s leading brigade soon brushed Lobau’s men away from their forward position, so Mr Sheep, perfectly sensibly, pulled back, anchoring his right flank in Plancenoit and taking up a position to cover Napoleon’s right. The slogging battle for Plancenoit was about to begin. Also at about this time, the leading elements of Ziethen’s corps began to appear on Wellington’s extreme left flank. At first there was some confusion, with Prussian black mistaken for French blue, but Major General Muffling had been sent over by Wellington to coordinate the Prussian arrival and a serious friendly fire incident – or what the modern army calls a ‘blue on blue’ – was averted.* From Napoleon’s perspective, the arrival of the Prussians in force was serious, but not yet a deciding factor. There was still time to beat the English before the Prussian intervention swung the balance, and soon it looked as if that might indeed happen.

La Haie Sainte had been under almost continual attack all day. Time and time again the French had come forward, and time and time again they had been beaten off by the riflemen of the 2nd Light Battalion of the KGL. During the night of 17/18 June Baring’s men had done their best to put the farm into a state of defence, but their efforts had been hampered by the withdrawal of their pioneers to work on Hougoumont farm. Nevertheless, they had managed to loophole the walls and build a roadblock on the Brussels road. What they had not managed to do was compensate for the missing gate leading into the farmyard on the west side. Whether this had always been missing or whether it had been used for firewood by the soldiers during the night is not known, but it was a weakness of the defence and would remain so.

From the French position, the La Haie Sainte complex consisted of an orchard thirty yards across and forty deep running along the road, then a barn and a wall, then the farmyard, then the house, and finally a garden to the rear. Baring’s initial deployment was to put three companies in the orchard, two in the buildings and one in the rear garden as a reserve. During the initial French assault by Charlet’s brigade of d’Erlon’s corps, the defenders of the orchard were driven back into the farmyard, and in subsequent attacks the French infantry concentrated on trying to force their way through the gateless entrance on the west side. This was defended fiercely, to such an extent that the bodies of seventeen dead Frenchmen were piled up as a barricade across the gateway. Baring’s men were taking heavy casualties, however, mostly outside the farm in the orchard or by the west gate, and on two occasions reinforcements were sent down to him, once of a KGL light company and once of a detachment of Nassau infantry. On occasions the French got so close that they attempted to wrest the rifles from soldiers firing from loopholes. At one point the thatched roof of the barn was set alight, whether deliberately by the French or by the burning wads of the battalion’s rifles we do not know, and the cooking pots carried by the Nassau soldiers were pressed into service to carry water from the pond in the yard to douse the flames.

In the constant fighting for La Haie Sainte, Baring’s men were beginning to run out of ammunition, despite beginning the day with sixty rounds a man. An officer was sent up to the crossroads to ask that more should be sent down, but none came. As the afternoon wore on, increasingly frantic messages were sent, but to no avail: no ammunition appeared. Finally, when Baring’s men were down to three or four rounds a man, a messenger was again sent back up to the ridge to say that without an instant resupply of ammunition he would not be able to withstand another attack. Ammunition still did not come, but French infantry supported by cavalry did. Despite desperate work with the bayonet, once the French got onto the roof of the barn and forced their way into the courtyard via the palisade of their own dead countrymen, the Germans were forced to withdraw into the farmhouse itself, after which that bloodiest sort of warfare – close and in built-up areas – was soon over. French infantry cleared the house room by room and gave no quarter – and to be fair to them, when the enemy is but a bayonet’s length away, it is too late to surrender. The survivors of the garrison could do no more than try to extricate themselves by the back door and retreat to the relative safety of the ridge.

It was while this final, hopeless defence of La Haie Sainte was in progress that a further disaster befell the infantry. Seeing that the farmhouse was about to fall, Colonel Christian Ompteda, commanding the 2nd KGL Brigade (Baring’s parent formation), stationed to the immediate west of the crossroads, was ordered to counter-attack. There is some doubt about who ordered the counterattack – some say it was the Prince of Orange himself – but in any event Ompteda personally led the 5th Line Battalion, recruited from the Lüneberg area, down the slope towards La Haie. With the large number of French cuirassiers milling about, the sensible formation for this move would have been to do it in square. Advancing in square was not easy but it could be done, albeit not as swiftly as moving in column or in line, but Ompteda deployed the battalion into line. Again, it has been suggested that Ompteda was ordered to advance in line by the Prince of Orange, thus repeating his error of Quatre Bras two days before, or that the order was given by his divisional commander, Lieutenant General Sir Charles (Karl) Alten, who assuredly should have known better. The result was entirely predictable and the end was swift. Ompteda was killed, his battalion routed and La Haie Sainte abandoned. Of the total of around 500 men who had defended the farmhouse – Baring’s own battalion plus the reinforcements sent to him – only forty or fifty men were still there at the last, unwounded and capable of carrying on.37

There have been a number of explanations offered for the failure to resupply Baring with ammunition – and if he had been resupplied, he could almost certainly have held on – ranging from administrative incompetence on the part of his battalion rear echelon and quartermaster or by his parent brigade, to a report of an ammunition wagon of the KGL overturning on its way up to the battlefield. Of course, rifle ammunition was in much shorter supply than that for the larger-calibre musket, with which the majority of the troops were armed, but the 1/95th Rifles, who were also armed with the Baker rifle, were less than a hundred yards away on the other side of the road and had no problems with ammunition. It does seem extraordinary that the KGL could not obtain ammunition from them – perhaps Baring’s emissaries came up against a quartermaster who refused to issue anything to anybody not of his own regiment, whatever the situation. Such military jobsworths were and are few, but they did and do exist.

It was during this last attempt to hold La Haie Sainte that rockets were used for the first and only time in the campaign. Earlier in the year there were several rocket batteries in the British contingent, but Wellington had ordered that those batteries were to hand in their rockets and draw guns instead. Wellington had seen rockets in the Peninsula and, although by no means a technophobe, he was not impressed: they were too inaccurate, had a nasty habit of circling round and coming whizzing back at their firers and, in the duke’s opinion, did little but frighten the horses. Only Captain Edward Charles Whinyates, a 33-year-old commander of a horse artillery battery, managed to retain a rocket section, as well as five six-pounders. When Wellington heard that Whinyates had kept his rockets and that it would break his heart to abandon them, the commander of the forces is said to have replied, ‘Damn his heart, tell him to draw guns.’ It took a brave man to disobey a Wellingtonian order, but at the height of the struggle for La Haie Sainte Whinyates and his men came forward to the crossroads on foot, laid their rockets on and through the roadblock on the Brussels road, lit the blue touch-paper and retired. The rockets had no effect on the outcome, but their firing would have given great pleasure to Whinyates and his rocketeers. His disobedience was not held against him and he was later knighted and eventually became a full general.

With the constant attacks on La Haie Sainte and the increasing effectiveness of the French artillery as the ground dried out, Allied casualties were mounting. In the main field hospital, in the farm of Mont-Saint-Jean, the piles of amputated arms and legs were growing as the queues of wounded waited for attention. The standards of military medicine had improved hugely since 1793, when medical officers were required to purchase their commissions and pay for their own instruments. Then no formal qualifications were required and surgeons learned on the job, usually by killing most of their patients. Properly qualified medical men had no interest in joining the army when they could earn far more in civilian private practice. It was the Duke of York, as commander-in-chief, who insisted that matters must be improved. Henceforth, medical officers would be commissioned free of purchase, their equipment would be provided, and they would be required to have graduated from a recognized medical school (in the event, mostly from Edinburgh).

Most battle wounds were caused by bullets, blast or edged weapons. The ball from a smooth-bore musket, being of relatively low velocity, was unlikely to kill unless it hit a vital organ. Medical officers were skilled in probing for the ball and extracting it; the trick was to remove the detritus that the ball drove into the wound – bits of jacket and shirt and general muck. If this was not removed, then the wound would turn gangrenous, leading to amputation if in a limb, and death if in the trunk. It was for this reason that one sees so many letters home from officers asking that white linen shirts should be sent to them: a clean shirt put on before a battle reduced the risk of infection. The survival rate of officers wounded was better than that of Other Ranks, not because they received priority – casualties were treated in strict order of arrival at the hospital, regardless of rank – but simply because the private soldier was issued with two shirts: one he had sold for drink and the other had not been washed for a very long time, hence there was a far higher risk of infection.

Medical men of the time were largely ignorant about sepsis, but they did know about shock, where the blood pressure drops swiftly, leading to vital organs ceasing to function, so if amputation was required, it had to be done swiftly. Surgeons were supposed to be able to amputate a leg in under a minute – some claimed they could do it in twenty seconds. The wounded man would be held down by sturdy surgeon’s assistants, given a slug of rum in lieu of anaesthetic and a stirrup leather to bite on. The flesh would be cut through by a tool shaped like a small sickle, the bone sawn through, the arteries sewn up, a flap of skin sewn over the stump and the whole cauterized by tar. The amazing thing is that in around 60 per cent of amputations of legs at the thigh patients survived, and for amputations below the thigh the survival rate was 75 per cent.38

Some medical procedures were primitive, though, and had no scientific basis whatsoever. During the advance by d’Erlon’s corps, Lieutenant George Simmons of the 95th Rifles was in the skirmish line and turned to give an order to his men when he was hit in the back by a French musket ball. It broke two of his ribs, went through his liver and lodged in his lower breast. Unconscious, he lay there until the French infantry had retreated, when his sergeant found him, got him on a loose horse and took him to Mont-Saint-Jean hospital. There Assistant Surgeon James Robson cut under his right breast and removed the ball. He then took a quart of blood from his arm. The next day Simmons was bled again, and again daily, until by 3 July, long after the battle, he was vomiting and in great pain with a swelling where the surgeon’s knife had cut. The swelling was lanced, more bleeding carried out and leeches (he says twenty-five) applied to his sides. Extraordinarily, after several weeks of this barbarous treatment, Simmons recovered and was able to return to duty, although ever afterwards he had to wear stays, and he died in 1858 aged seventy-two.39

Now, around 1830 hours, came the crisis of the battle. More and more of Wellington’s reserves had been called forward to plug the gap in the centre, and Marshal Ney had ordered artillery forward to La Haie Sainte and sent an ADC back up the hill to Napoleon asking for the immediate despatch of infantry: here was the chance to burst through the Anglo-Dutch centre, roll up the line, and win the battle before the Prussians could interfere. But Napoleon had more pressing problems to attend to, for the Prussians were posing a far greater threat than anything Wellington might do. Bülow had been ordered to attack the village of Plancenoit, partly to draw Napoleon’s troops away from Wellington and partly to procure a jumping-off area for an attack on the French right rear. He deployed Hiller’s brigade of nine battalions to the left (south) of the road leading from the Bois de Paris to Plancenoit, and Losthin’s brigade – now of seven battalions, two having been sent off to reinforce Saxe-Weimar at Papelotte – to the north, on the right of the road. Each brigade was preceded by its own integral cavalry squadron and had its divisional artillery battery of six six-pounders and two howitzers close up. The River Lasne, to the south of the village, ran through a deep ravine, so a head-on attack was the only option. At about 500 yards from Plancenoit, both divisional artillery batteries moved forward, unlimbered and began a bombardment of the village, which lasted around ten minutes. Then six of Hiller’s battalions, in battalion columns, attacked the village, while Losthin watched his fellow general’s right flank and engaged Lobau’s second brigade, which was astride the road facing east.

Although the village of Plancenoit had not been prepared for defence, it was immensely strong, and the high walls of the cemetery around the church gave the French excellent cover and the Prussian infantry a severe obstacle to get over. French artillery was in the village and opened up with canister, and the fighting in the cellars and the rooms of the stone cottages was bloody and brutal, with bayonet and musket butt more effective than powder and shot at close quarters. Eventually, after thirty or forty minutes’ fighting the Prussians of Hiller’s brigade forced their way into Plancenoit and Lobau’s surviving defenders withdrew, with his other brigade withdrawing to avoid exposing their right flank. Prussian round shot that had gone over Plancenoit bounced behind the French centre, on the Brussels road along which the Imperial Guard were waiting, as yet unblooded in this battle, and the realization that the next Prussian move would be to attack the French rear made it imperative to retake Plancenoit. Major General Philibert Duhesme was ordered to take his Young Guard Division, of eight battalions of elite light infantry, to restore the situation. Duhesme, despite his recall from Spain in disgrace, was remembered more for his capture of Barcelona by a ruse.* He fought in the 1814 battles in northern Europe and became inspector general of infantry during the brief Bourbon restoration, before joining Napoleon once again and being given command of the Young Guard.

The Guard, with the remnants of Lobau’s division, attacked Plancenoit from the west, and again fighting around the church was particularly severe, with Duhesme being wounded in the head (he died in Genappe a few days later). At last the Guard managed to push the Prussians out of the village, only for them to reorganize and come on again. Plancenoit could not be lost – it was critical to the French ability to remain on the Belle Alliance ridge – so the emperor sent another two battalions, from the Old Guard this time, to reinforce. The first battalion of the 1st Chasseurs à Pied and the first battalion of the Grenadiers à Pied swung off the Brussels road and along to Plancenoit. For the moment, the French could hold.

Meanwhile, Marshal Grouchy was fighting his battle at Wavre, eight miles away. There the French were still trying unsuccessfully to storm the bridge into the town. In the greater scheme of things, they were achieving absolutely nothing – Thielemann’s Prussians had only to keep Grouchy occupied and prevent him moving off to join Napoleon, which most of his senior commanders wanted to do (or so they said, in the blaming and counter-blaming that followed the campaign). There was now not the slightest possibility that Grouchy could affect the outcome of the battle in any way.

But now, at La Belle Alliance, came Ney’s urgent, hysterical demand for infantry to exploit the capture of La Haie Sainte. ‘Infantry, where am I to get it? Does he expect me to make it?’ was, supposedly, Napoleon’s reply to the wretched ADC bringing the message. And in truth the emperor had very little infantry left. Reille’s corps was still battering ineffectually at the walls of Hougoumont farm, d’Erlon’s men had captured La Haie Sainte, while his right wing was engaging Saxe-Weimar and the increasing numbers of Ziethen’s Prussians. Lobau’s corps, the Young Guard and two battalions of the Old Guard were tied up in the struggle for Plancenoit, and all that was left were twelve battalions of the Old and ‘Middle’ Guard, between 5,000 and 6,000 men altogether. That, though, was what the Guard was for – to pluck victory from the jaws of defeat; and with them Napoleon might – just might – be able to finally turn the tide of battle, if he could only beat Wellington before the Prussians enveloped his rear. It was the last throw, a desperate gamble, but it was all that was left, the last chance for a Bonapartist Europe.

One of these battalions was still at Le Caillou, the overnight billet, and two were left at La Belle Alliance as a rearguard. The remaining nine battalions formed on the French ridge and began to move down the slope in two columns, led by Napoleon in person.* The firing from off to the right, from the direction of Papelotte and Plancenoit, was announced to the men as heralding the arrival of Grouchy, and there can be little doubt that the sight of the emperor in person, at the head of his Guard, lifted French spirits – just one more push, and victory would be theirs. The Guard reached the valley, and at a cottage, which is still there, argument broke out between the emperor and his staff. Napoleon, who had little regard for his own life (or for anyone else’s), seems to have genuinely intended to lead this last attack in person, an attack that would save France, but he was persuaded that he was France and that, if he died, the imperial ideal would die with him. He handed over to Marshal Ney.

One of the great mysteries surrounding this final assault by the Guard is why they did not attack straight up at the crossroads, at the centre of the Allied line. That was Wellington’s weakest point (although Ziethen’s arrival on the left flank did allow some Allied troops to be moved across to fill in the gaps) and it was on the shortest route from La Haie Sainte, now in French hands. As it was, the Guard moved diagonally across the valley to their left and up the slope, emerging on the crest in front of the British Guards Division and Halkett’s Hanoverian Brigade. It may be that the roadblock had not been demolished and the columns were attempting to bypass it and went too far off course; it may be that sniping from the 95th Rifles forced them to edge over to their left; or it may be that Ney thought the afternoon-long cavalry attacks and the fighting at Hougoumont had seriously weakened that part of the Anglo-Dutch front. But in any event it was the wrong decision – if decision it was.*

Despite the failure of the French army to make any great impression on the Anglo-Dutch so far, the guardsmen tramping up the slope would have been confident that once again they would triumph and secure victory for their emperor. They had waited well behind the French front line until called for, and had thus been sheltered from the effects of the battle so far. Impressive in their greatcoats and bearskin caps (although without their full dress tunics and plumes, which were rolled up inside their packs to be worn for the victory parade in Brussels), muskets at the shoulder and with their band playing behind them, they would have seen little, for, although the rye grass and the maize had been trampled down by the mass cavalry attacks, only the muzzles of the Allied artillery were visible – and even those were masked by the gouts of yet more black smoke that belched forth as round shot and then canister tore great holes in the French columns, before the gunners abandoned their pieces and retired to the rear. But the Guard could withstand punishment and still they came on, until as the columns breasted the ridge, they were greeted by a scene of utter devastation: dead horses, dying horses, wounded cavalrymen, ploughed-up ground and all the detritus of the afternoon’s fighting, and beyond that, the lines of red-coated British and Hanoverian infantrymen climbing to their feet.

Wellington, with that extraordinary knack of his of always (or nearly always) being present at the critical juncture, had been sitting on his charger behind the Guards Division, whose soldiers had been lying down. ‘Now, Maitland, now’s your chance,’ said the duke, and Maitland’s two battalions, followed by Byng’s two, began to fire volleys at a range of no more than fifty yards and probably less. Although British military legend has it that the Imperial Guard were seen off by the British Guards alone (with a little help from the 52nd Light Infantry), there was much more to it than that. The right-hand French column at least managed to penetrate some way over the ridge, for von Kruse’s three-battalion Nassau brigade, mainly of soldiers without experience but led by officers with plenty, also found themselves firing defensive volleys, while the 33rd Foot of Major General Sir Colin Halkett’s brigade recovered whatever reputation they may have lost at Quatre Bras.

By now Adam’s brigade, initially in reserve, had been moved forward to the right of the British Guards. Of three battalions and two companies of the 3rd Battalion 95th Rifles, it contained what was probably numerically the strongest battalion in Wellington’s army, the 1st 52nd Light Infantry, commanded by Colonel Sir John Colborne.* While the purchase system generally worked well and, by 1815, British brigade and divisional commanders were competent and experienced men, it did not work well for Colborne, at least not initially. Colborne’s father, a Hampshire landowner, had lost most of his money speculating on the stock exchange, and while there was enough left to get John, a younger son, through Winchester, there was none to purchase him a commission. Fortunately the Earl of Warwick was a friend of the family and secured the sixteen-year-old John a free commission as an ensign in 1794. Almost immediately on active service, he obtained promotion to lieutenant as a result of battle casualties and a captaincy in 1800 aged twenty-two, both without purchase. He had to wait eight years before promotion to major without purchase as military secretary to Sir John Moore. He accompanied Moore to Spain, served in the retreat to Corunna and was again promoted, to lieutenant colonel free of purchase, in accordance with Moore’s deathbed recommendations. He served with considerable distinction in the Peninsula and, although only a lieutenant colonel, successfully commanded a brigade on several occasions. At the end of hostilities in 1814, he was promoted to colonel and knighted in January 1815. It was Colborne’s misfortune that from lieutenant colonel upwards promotion was by seniority, and not enough generals were being killed (although not for want of their trying) for the available vacancies to reach as far down as Colborne. Had he been able to purchase, he could well have been a lieutenant colonel early enough to have been a general by 1810 or 1811, as some officers of his age were. Colborne would unquestionably have been an excellent general, in command of a brigade or a division, but as it was he did not become a major general until 1825, although he did become a field marshal and a peer eventually.

Colborne saw what was happening to his left front, and on his own initiative swung his battalion around ninety degrees, put them into line and ordered volley-fire into the flank of the left-hand Imperial Guard column. This was not without risk: the 52nd’s right flank was exposed; there was French cavalry milling about Hougoumont that might charge it; and the French Guard did momentarily halt and reply with at least one volley, which killed Ensign Nettles, who was carrying the king’s colour, thought lost until it was found under his body after the battle. In the regiment’s account, published in 1860 and whose editor had interviewed the 85-year-old Colborne (then Lord Seaton), it is claimed that the 52nd drove the Imperial Guard back as far as the Brussels high road, where the French ran ‘like a mob in Hyde Park’, and then formed into column and advanced southwards along the road, passing the French Grand Battery and halting in face of the French rearguard drawn up at La Belle Alliance. It was some time later that other ‘red regiments’ came up to support the 52nd.40

There are, of course, lies, damned lies and regimental histories. The accounts by those who were there (not only that of the commanding officer) are not deliberate untruths but what participants thought had happened, and in the gathering dusk and the clouds of smoke they no doubt did think that it was the 52nd that won the Battle of Waterloo. Any account of a battle can only be a balance of probabilities, but with the Imperial Guard under fire from artillery as it came up the slope, then finding itself under close-range fire from four battalions of British Guards, two battalions of Adam’s brigade and three of Nassauers, and then coming under fire from the flank as well, it is hardly surprising that it broke. The watchers at La Belle Alliance, peering anxiously at their last possible chance of salvaging something as Plancenoit behind them once more fell to Bülow’s Prussians, with those of Pirch pressing on in support, could see little. But then guardsmen began to emerge from the smoke stumbling back down the hill – individuals at first and then little groups, and then whole companies. ‘La Garde recule!’ was the cry. The immortals, the elite of the elite, the crème de la crème of the French army, were beaten, something that no French soldier on that field had seen before. The French army was brittle and now it broke, amazingly quickly. The Guard was scattered, the units that they had been told were Grouchy’s were firing on them: treason was the cry, followed by ‘Sauve qui peut!’ At La Belle Alliance what was left of the Imperial Guard formed three squares, with two guns and a handful of cavalry in support, to allow the emperor to get away – back to Rosomme on his horse, and then transferring to a coach in which he hastened for Paris.

On the ridge of Mont-Saint-Jean the Duke of Wellington raised his hat and ordered a general advance. The great battle was over.

* His name was Georges Mouton but he was officially known by his ennobled title, Comte de Lobau, which he had acquired after performing well in the 1809 campaign against the Austrians (Lobau is an island in the River Danube).

* The Guards had colonel’s, lieutenant colonel’s and major’s colours as well as company colours, while rifle regiments (the 95th and the 60th) had no colours at all.

† Until very recently the only British regiment still on the army order of battle to have its colours exhibited as captured trophies of war was the Royal Scots, whose fourth battalion lost theirs at the Battle of Bergen op Zoom in 1814. They can now be seen in the museum of Les Invalides in Paris. The Royal Scots have since been subsumed into the Royal Regiment of Scotland.

‡ Colours were last carried into battle in 1881, during the first Boer War, and are now only carried on ceremonial occasions. They are still highly regarded, however, are still consecrated, and are saluted by all ranks. They are now only 3 feet 6 inches by 3 feet in size and carried on a pole that is 8 feet 7 inches in length, which makes them a lot easier to carry. On a battalion giving a general or royal salute, the regimental colour is lowered, but the king’s or queen’s colour is lowered only to the reigning monarch, his or her consort, and the heir to the throne.

* The suggestion that Napoleon was not present on the field is reinforced by Milhaud’s acceptance of Ney’s orders without appealing to the emperor.

† Whose No 1 Squadron was entirely Polish and wore blue, but it is such inconsistencies that delight the observer of la vie militaire.

* Except for the men of Mercer’s troop, who took cover under their guns. Mercer thought that the nearest infantry square, that of Brunswick, was unsteady and might panic if they saw the gunners running towards them. Despite the continual passage of French cavalry, his men remained unscathed, emerging to service the guns when an opportunity arose.

* Readers who hunt (most, I fondly hope) will know that it is pointless to gallop at a hedge that the horse decides he cannot jump. The rider may well clear the obstacle, but without his horse.

* For the benefit of readers who are not British, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals is an organization that does a great deal of good work to ensure that animals are treated properly; it also has a tendency to spend large amounts of its supporters’ money engaging in class warfare against packs of foxhounds.

* Until the First World War British maps always showed the position of friendly troops in red (British soldiers had worn red coats for much of their history) and enemy troops in blue (the enemy had usually been the French). French maps, with the same logic, used the reverse system – enemy in red, friendly in blue. When the First World War broke out, it was obvious that for the two now allied armies to retain their existing map-marking conventions could be confusing (to put it mildly), and so the British changed to the French system. Hence ‘blue on blue’ means friendly forces firing on each other.

* He had persuaded the Spanish governor to permit the entry of a column of French sick and wounded. Once within the fortifications the sick and wounded leapt from their stretchers, produced concealed muskets and overpowered the garrison.

* There is considerable disagreement among historians (French, British and German) about exactly how many and which battalions of the Guard were involved in this final effort, and what formation they were in. What follows seems to this author to be most likely, but he would not regard it as a resigning issue if he was wrong.

* Some years ago this author carried out an experiment on the field of Waterloo using a platoon of his own soldiers, there taking part in an exercise with the French army. The Gurkhas were formed into a column (albeit one much smaller than the French) and briefed to advance on the Allied centre keeping to the left (west) of the Brussels road. They were then told to tie their camouflage face veils over their eyes, thus restricting their vision and so replicating the clouds of black smoke hanging over the battlefield on 18 June 1815. The order to advance at a steady pace was given, and the men emerged very much as the real Guard had done, for if an aiming point to head for cannot be seen, the shape of the ground pushes walkers over to the west.

* It had not been involved at Quatre Bras and mustered around 1,000 all ranks.