4 Building a Better Lobster Trap

The lobsters catch themselves, for they cling to the netting on which the bait is placed of their own accord, and thus are drawn up. They sell them for two cents apiece. Man needs to know but little more than a lobster in order to catch them in his traps.

Henry David Thoreau, 18651

John Whittaker’s lobsterboat Whistler smells of fishy labour, but it is not rank unless a bait barrel is left open, attracting both flies and gulls. Whistler is 13 metres (42 feet) long and has the classic lines of a New England lobsterboat: a high, proud bow to cut through the seas, a covered house forward, then a rail that smooths aft into a low, wide stern that adds stability and is easier for working the traps. The boat is fitted with radar to find the way in the fog and with a modest array of electronics to help find his gear. Whittaker can steer from inside or from the open area beside the port rail, from where he hauls the traps. He brings these pots to the surface by hooking a buoy with a gaff, leading the attached line through a pulley on a davit, and then inboard around a spinning hydraulic drum. Banging hundreds of pots each day against the port side of the hull has rendered it scratched and scarred, like the skin of an old warrior seal.

Securing a lobster, like catching a mouse, is a simple matter in concept but not always so in practice. Historically, people throughout the world waded into shallow waters for lobsters, hitching them with gaffs, poles and spears. They tangled lobsters in nets, nabbed them with snares or free-dived and snatched the lobsters out of their dens.2 All sorts of commercial and recreational fishermen searching for clawed, spiny and slipper lobsters – from Norway to Namibia, from Belize to Bangladesh – have tried at its plainest to attract these crustaceans, pull them undamaged to the surface and then have a method to bring the lobsters ashore and preserved for the consumer’s kitchen. In recent times, almost wherever you are, catching a lobster is rife with complications and intricacies. As a commercial or even a recreational endeavour it usually requires a significant financial investment, an understanding of government regulations and an enormous and varied store of knowledge, experience and good fortune.

Even in the same general location fishermen often employ a few different strategies to catch a lobster. Around the coasts of Ireland and England, for example, fishermen have been catching clawed and spiny lobsters by traps, diving, and thin-meshed nets. In the waters of Hawaii Euell Gibbons described his experience as a commercial and recreational catcher of spiny lobster. He caught these animals with traps, with nets at times 1,000 feet long, and even with a fishing pole with a three-pronged hook and a piece of bait. Gibbons wrote:

All these ways of catching Spiny Lobsters are fun, but the way to wring the maximum amount of sport from this creature is to dive down to the bottom and catch it with nothing but your hands . . . Wear a pair of heavy gloves . . . You may carry a spear, but use it only on those that are in holes too deep for you to reach them. When you get a Spiny Lobster in your hands, hold on for dear life. It will flap that strong tail mightily, and set up a terrible commotion, and the first time this happens most neophyte divers panic and let go. It is all bluff, and you can soon have your Spiny Lobster safely into a bag if you just hold on.3

With the popularization of scuba diving, beginning in the 1950s, people began collecting underwater animals more easily and in deeper waters, rendering lobsters, as Gibbons put it, ‘at your mercy’. Diving for lobsters has since been regulated on several coasts. In southern California, for example, a diving recreational fisherman is restricted to a certain number of legal-sized lobsters per day, scuba gear isn’t allowed in all areas, and a person may only dive during a specified season and only with hands – no spears or other tools. The Kuna Indians of Panama’s San Blas region have outlawed scuba diving for the commercial catch of their spiny lobsters (Panulirus sp.), allowing only free-diving with masks, flippers and snares from canoes during daylight hours.4 The regulations for the Galápagos Islands aren’t quite as strict, as they allow diving for spiny and slipper lobsters (Panulirus penicillatus and P. gracilis, Scyllarides astori) from a small boat, usually at night, with the aid of hoses pumped with compressed air, a ‘hookah’ system.5 In Australia and Papua New Guinea lobstermen use a similar hookah method in the Torres Strait; they also free-dive for their Ornate spiny lobster (P ornatus), as do men in Thailand and the Philippines.6

A wooden tool for catching crustaceans, carved by the Yahgan peoples of Tierra del Fuego. |

If you don’t want to get wet, a popular early lobstering device used into the nineteenth century in Britain and consequently in North America was the hoop net: a netted pouch woven onto a cylindrical wood or metal ring, often made from a barrel hoop, with bait suspended over the top. The hoop net required tending from a rowing boat, and a fisherman had to pull up the line at the right time, before the lobsters crawled elsewhere.7 Recreational fishermen still occasionally use hoop nets today, often from a kayak.

In the early Norwegian lobster fishery men used tongs that measured about 3.5 metres (12 feet) long, which they wielded over the side of a boat in the same way oyster tongs were once used. Some Norwegian lobstermen used lobster tongs into the nineteenth century but the Dutch, encouraging them to catch lobster more efficiently and not damage the animals with the tongs’ tines, introduced as early as 1717 a basket-style trap to the Norwegian coast. The Dutch seem to have adapted the idea from their eel trap.8 It remains difficult to say, however, which culture first invented the transportable trap intended primarily for lobsters–one that allows a fisherman to leave it and return some hours or days later to retrieve his or her loot. This type of trap enables a lobsterman to fish deeper waters and set more pots.

Traps remain the most common lobstering tool around the world. Numerous types, assembled in a variety of shapes and sizes, have been used and deployed in all oceans, for dozens of species of lobster. Fishermen along the coasts of Japan, India, South Africa, Hawaii and the Canary Islands all use different styles of lobster traps, yet all the pots serve in roughly the same way. British fisherman-author Alan Spence, writing about the different traps around Britain such as the ‘inkwell’ design of the English Channel versus the French ‘barrel-style’, explained: ‘Each community likes to think that their design is superior to all others in catching and holding qualities.’9 Some variations are better suited to local conditions and supplies, while others are simply regional, traditional constructions, no more effective than any other. Fishermen first built their traps with materials such as wood, bamboo, willow, wicker, leather and natural fibre netting, but now most are made with at least some metal or plastic. Nearly all types of traps have a funnelled entrance, which serves as a type of one-way valve, designed so lobsters cannot climb back out after they’ve been enticed inside by some sort of bait.

A lobsterman flings an inkwell-style lobster trap over the rail, just off the coast of Inishmore, one of the Aran islands off the Atlantic coast of Ireland. |

John Whittaker’s lobster pots, like those throughout New England and Canada, are built of vinyl-coated wire, are rectangular and are larger than most dormitory refrigerators. Even before anything is caught inside or growing on the frame, Whittaker’s traps are back-breakers, each weighing 29–32 kg (65–70 lb). In part this is because every pot is fixed with several bricks or a slab of cement so it will sink quickly, land correctly and stay put against powerful currents, even when dropped as far as 107 metres (350 feet) below the surface.10 Each trap has a door at the top to allow access for hanging bait and removing, ‘picking’, the lobsters, and two compartments. One, called ‘the kitchen’, has two netted funnel heads for the lobsters to enter as they hunt for the bait hung in the middle of the trap. After snacking in the kitchen, the lobster then crawls through an internal funnel that is presumably easier to navigate than the ones it used to enter, but this funnel leads into a second compartment, ‘the parlour’, in which the lobster cannot seem to go anywhere.

From an environmentalist perspective lobster traps are much better for ocean ecosystems than trawl, trammel or tangle nets. Pots have minimal by-catch and they do much less damage to the sea bottom since they remain relatively stationary. Wooden traps – still used in many parts of the world – cost more these days to make and maintain and are subject to rot and marine fouling. This degradability is a positive feature if you’re a lobster. If a fisherman loses a trap on the bottom, perhaps due to a storm or the cutting of the buoy line by a propeller, a wooden pot will eventually break up. Plastic or metal gear, on the other hand, takes longer to decompose and can continue catching lobsters for years, known as ‘ghost fishing’. Lobsters can survive quite a while in a trap. They can eat plankton or dine on other captured creatures – a crab, a fish, an eel, another lobster – or find sustenance from the thick fouling community that often forms on the pot itself. Depending on the coast and the nature of the bottom, traps regularly arrive on the boat’s rail with little jungles of algae, barnacles, mussels, sponges, sea squirts, skeleton shrimp, crabs and sea stars. And even if a lobster starves to death in the pot, it might serve as bait for other animals – so this ghost trap business can be an unseen cyclical problem.

A wooden trap on the ocean bottom, illustrating W. H. Bishop’s The Lobster at Home in Maine Waters (1881).

To avoid ghost traps, laws in several lobster fisheries require a removable ‘escape vent’ fixed with biodegradable metal clips. If the pot is lost on the ocean bottom, this vent will eventually break off and the lobsters can climb out. Some regulations require that the vent has a plastic opening of a specified width, allowing smaller lobsters that are not close to legal size to swim free.

Though wire traps stack more easily, last longer and are cheaper to make and repair, their use, first developed for the offshore lobster fishery, has not come without a certain reluctance. Like most new fishing technologies, especially sonar and the hydraulic trap hauler, the wire pot is one more convenience that encourages more people to go out and lobster. Vivian Volovar, author of her own children’s book, Lobster Lady (2007), has been fishing for bugs almost as long as Whittaker. Volovar said:

Most of these fishermen, they can’t fish now without all the electronics, they can’t tell what the wind’s doing or what’s going on . . . They got all the brand new wire gear because they got something else supporting them . . . Can you knit funnels? No. If they couldn’t buy everything they had, they couldn’t fish. They don’t know how to build pots or do any of this stuff. They got into the business because they had a lot of money behind them. And a good credit card.11

The majority of lobstermen fish in fairly shallow water and close to the coast, but a few lobster fisheries seek the animals in deeper seas. The North American offshore lobster fishery peaked in the 1970s, but a small number of boats still lobster hundreds of miles from land. They fish more traps on a string and use larger boats that require more industrial gear. One offshore lob-sterboat in 2008, for example, fished over 240 km (150 miles) off the coast of New Jersey in approximately 150 metres (500 feet) of water. The crew hauled strings of 50 pots, each weighing some 45 kg (100 lb). They were out for a week at a time.12 Large fishing vessels engaged in the spiny lobster fishery (Palinurus gilchristi) off South Africa can carry some 2,000 plastic traps aboard and set strings of 100–200 pots on one string, sinking them as deep as 200 metres (650 feet). A few of these vessels have the technology to freeze the tails immediately on board.13

The faster and bigger boats, the improved navigation systems, the wire traps, the synthetic ropes, the powered pot-haulers – it all just means that lobstermen can fish more gear, more often, in deeper water and in most weathers. More lobsters are being caught globally and there are more traps on the bottom trying to capture those that are left. Several lobster fisheries have experienced booms and busts, as seen in Brazil (Panulirus argus and P. laevicauda) and India (e.g. Thenus orientalis), which both saw prolific years in the second half of the twentieth century, fluctuations and then a steady decline, from which the stocks remain tenuous.14 On many coasts, such as in the Galápagos, when spiny lobster populations were overfished, men went after the less profitable slipper lobsters.15 Fishing practices have had an effect. Throughout Europe and the Mediterranean, for example, the use of thin-meshed nets beginning in the 1960s put a huge strain on the spiny lobster populations.16

Scottish fisherman’s gauge to determine the legal size of a lobster that may be brought to shore. Lobster was measured from the beak, or rostrum, to the end of the tail. Engraved on the other side is ‘IV. Lobster Act 1877’.

Government managers have used a variety of tools to regulate regional lobster industries. It can be slightly easier than other fisheries since crustaceans are less mobile but, at the same time, the variety and length of highly transient larval stages make predicting stock sizes a challenge. There is never enough ecological information to make confident management decisions, especially with lesser known spiny and slipper species.

Several lobster fisheries limit the number of commercial or recreational traps per person, and some have limited the number of people that can be involved at all. A few countries have lobstering seasons, such as Spain, Greece, Australia and Canada. One management strategy, recently put in place by Brazil in an effort to keep track of its fleet of 800 or so lobsterboats, requires that every vessel be equipped with a satellite monitoring system.17 A strategy enforced in most spiny fisheries, as in Western Australia, is a scientifically determined annual quota that the collective fishermen in a given area may not exceed. This total allowable catch can keep prices in check while maintaining stocks.

One of the most common management tools used in nearly all lobster fisheries is the mandate to refrain from harvesting female lobsters with eggs visible under the abdomen, known as ‘eggers’ or ‘berried’, or even to gather ‘brood-stock’ female lobsters that have been recently identified with eggs. To identify the latter, fishermen and managers in some countries cut a ‘v-notch’ in the tail-fin before they return an egger into the water so as to notify the next lobstermen. A v-notch can last for a couple of moults after a female has laid her eggs. Regulations in nearly all lobster fisheries declare a minimum size bug that can be brought ashore, usually measured by the length of the carapace. Managers sometimes set a maximum size as well to protect the most prolific breeders (while also helping the live-market dealers who have difficulty selling larger individuals to restaurants). Given these restrictions, most trap lobstermen spend the majority of their time throwing back lobsters, usually hoping for just a few keepers per pot.

After a lobsterman has learned the local regulations, he or she needs at least some understanding of economics. Lobster is a luxury commodity. The price a lobsterman gets for a catch is often out of his or her control and not even necessarily based on the health of the local population. Within the basic tenets of supply and demand a lobsterman is dependent on the consumer’s willingness to go out for a fancy meal – and lobster markets and products are expanding to literally all corners of the earth.

Because of the price fetched for a single animal and its coastal habitat, lobstering is one of the few commercial fisheries remaining that can be viable for one or two people. John Whit-taker, for example, is a single owner-operator. This makes him vulnerable to the cost of fuel and the price the draggers set for catching the majority of his bait. These bait-catching men, in turn, are also dependent on fuel costs, as well as immensely strict limitations for conservation purposes. Once Whittaker has caught the lobsters, he sells to a wholesaler, a fish market or directly to a restaurant. He does not have access to winter storage facilities, known as lobster pounds, to keep the animals alive to wait for better prices, as they do on a large industrial scale in Canada. Whittaker also has no local cooperative that he might join, which can help cut costs and negotiate collectively, a technique employed by fishermen in other parts of the US and Mexico. Meanwhile, to make matters still more competitive for Whittaker, the supermarket just a few miles from his dock offers frozen spiny lobster tails from Nicaragua and South Africa. Across the aisle gurgle live clawed lobsters in a tank with claw bands that say ‘Canada Wild’.

Beyond fishing technology, government regulations and the fluctuations of global trade, the lobsterman is also subject to small and large-scale environmental factors beyond his or her control. In Whittaker’s Long Island Sound the health and productivity of the lobster population has diminished due to several factors: large-scale die-offs to the west, an oil spill to the east, various types of industrial and coastal pollution, rising water temperature and a significant intraspecies shell disease. Somehow he has held on to his business, largely due to his experience, skill and hard work. Yet on the morning of 11 June 2010 he picked up his local newspaper before going aboard Whistler and read this headline: ‘Regulators weigh five-year lobstering ban in southern New England’.18

Several of the global commercial lobster stocks, like all the world’s fisheries, are in some level of decline. Diseases, viruses, overfishing, human pollution and climate change all threaten once vibrant lobster stocks in every ocean. A few lobster species are especially threatened regionally, such as the spiny lobster off the coast of South Africa and Namibia (Jasus lalandii), the spiny lobster off Taiwan (Panulirus japonicus) and the European lobster off the coast of Turkey.19 As of now, however, no commercial lobster species is on the endangered species list, although, in truth, it is difficult for invertebrates to get that sort of status. In 2009 a group of international experts met in Taiwan to determine if any lobsters deserved to be listed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s ‘Red List Index’. British zoologist Nadia Dewhurst wrote:

Preliminary results from the workshop indicate that a low proportion of the world’s lobster species [they count about 250] are threatened with extinction. However, over 40% of species have been preliminarily placed in the Data Deficient category, of which 80% are known from the Indo-Pacific region particularly around Japan, Taiwan, China, the Philippines, and Indonesia . . . The results do however highlight that lobster fisheries are in fact some of the best managed fisheries: all of the major commercial species . . . were assessed as Least Concern.20

The group pointed out that many lobster species have wide geographical ranges, which has helped their status, regardless of regional depletions. They felt that ‘poor fisheries management’ has led to their concern for the health of populations such as the Caribbean spiny lobster, the Juan Fernández spiny lobster, and the St Paul spiny lobster (Jasus paulensis).21

Meanwhile, a surprising and inexplicable success story has emerged with the American lobster in the Gulf of Maine, just a few hundred miles to the east of Whittaker’s Long Island Sound. These lobstermen are catching the same species but doing immensely better. Homarus americanus remains the lobster of highest international value and tonnage caught. Fishermen haul out of the sea tens of thousands of tonnes more of these bugs each year than those of any other lobster fishery on earth, employing some 40,000 commercial lobstermen and thousands more in shoreside industries.22 In 2004 The Lobster Institute estimated the economic impact of this fishery to be from US$2.4 to 4 billion.23 This craggy stretch of coastline, with its endless coves and islands, extends from about the Isle of Shoals eastward and northward, up around Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. On a much larger scale than anywhere else in the world the communities around the Gulf of Maine are dependent economically and even culturally on the harvest of lobster. Thankfully for them, despite highly intense fishing effort over the last half-century, this lobster population has remained seemingly vigorous. Many believe that it is one of the few healthy wild fisheries–of any marine species–left on our planet.

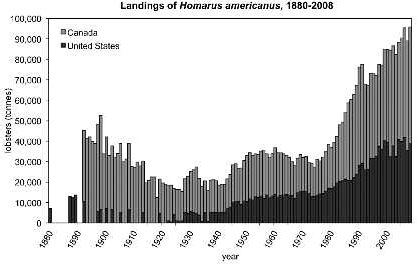

Landings of Homarus americanus in tonnes, 1880–2008. Several data points are missing for the US before 1950, and US landings before then include only those from the major lobster fisheries states, from Connecticut to Maine.

So why has this Homarus americanus fishery in the Gulf of Maine and the Canadian Maritimes fared so well? As with all fisheries questions, the answer is complicated and requires a look backward.

Commercial lobster fishing along these coasts actually did not get going until the mid-nineteenth century, primarily because of the challenges of shipping live product. Early settlers perceived abundant lobsters more as a local food source, as livestock feed, crop fertilizer or bait. During the eighteenth century, when the rebellious colonists were calling the red-coated British soldiers ‘lobsters’ and their ships ‘lobster boxes’, the fishermen in the regions of Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New York delivered live bugs in well boats to the urban centres of New York City and Boston. When these men could not meet the public demand, often because of overfishing, they sailed farther east, into the cold, productive, unspoiled waters of Maine. Here they set their traps, beginning around the 1820s.24 Just like the Norwegians toward the Dutch, the fishermen in Maine soon realized they could do the lobstering themselves, so they restricted this fishing to Mainers and began sailing their own vessels to deliver their bugs to the cities.

When canning technology, first invented and perfected in France and Scotland, arrived to the region in the 1840s, the game changed completely. Here was a shipment and preservation solution, able to expand both market and demand. Historians Martin and Lipfert point out: ‘It is a measure of Homarus americanus’s reputation among gourmets that it was one of the first items canned commercially in the United States.’25 The Lobster Rush was on.

Canning overtook the live market and dozens of canneries sprouted up along the coast. By 1880 there were 23 active canneries in the state of Maine, the majority built exclusively for lobster.26 Steamships carried about half of the canned Maine lobster and nearly all of the Canadian meat back to Europe, whose own lobster fisheries were much smaller due to oceanographic limitations and the fatigue of centuries of human impact.27

The Canadians were a bit slower to capitalize on the international value of lobster, but the fishery moved inevitably eastward. The lobster stocks around their coastline, according to a major government report, ‘need only be restricted by the demand, for the supply is almost unlimited’.28 In 1881 an English visitor named John Rowan observed with amazement that ‘lobster spearing’ was a sport in Halifax and that little boys collected hundreds with hooks and sticks off the shore. Rowan described farmers in New Brunswick fertilizing acres of potato fields with lobsters gathered from the beach after a gale. He wrote: ‘To give some idea of the little value put upon lobsters by the country people, I may mention that on some parts of the coast they boil them for their pigs, but are ashamed to be seen eating lobsters themselves. Lobster shells about a house are looked upon as signs of poverty and degradation.’29 There are accounts that fishermen bound for groundfish off the Grand Banks loaded their hold with lobsters to chop into pieces and stick on their hooks.30 Rowan anticipated that the Canadian lobster would be a high value export: ‘Is it unreasonable to expect that sooner or later some ingenious persons will turn these Nova Scotian lobsters into British gold?’31

‘Boiling-room’ in a lobster cannery, illustrating W. H. Bishop’s 1881 The Lobster at Home in Maine Waters. |

The lobster canning industry spread further into Atlantic Canada. According to Farley Mowat, in 1873 there was one factory all the way north in Newfoundland. Just fifteen years later 26 small canneries were boiling along, contracting over 1,000 fishermen and filling some 3 million 1 lb (450 g) cans of picked meat.32 Canneries used only the claws and tails, tossing or composting the remains. In 1881 W. H. Bishop observed at a cannery: ‘The scarlet hue is seen in all quarters–on the steaming stretcher, in the great heaps on the tables, in scattered individuals on the floor, in a large pile of shells and refuse seen through the open door, and in an ox-cart-load of the same refuse, farther off, which is being taken away for use as a fertilizer.’33

The Lobster Rush around the Gulfs of Maine and St Lawrence reached its peak in the late nineteenth century. Canadians averaged over 41 million kg (90 million lb) of lobster landed annually in the late 1890s, a harvest bonanza that they would not achieve again for nearly a century.34 As more men had been entering the business full-time, lobstering required more traps and more effort to gather continually smaller and smaller lobsters to fill the tins.

It is worth emphasizing here, however, that this nineteenth-century depletion of American lobster stocks, as had occurred earlier in northern Europe with Homarus gammarus, seems to be a result of intense effort and lack of regulation, not advanced technology. The regular use of the internal combustion engine and even the motorized trap hauler was still decades away.

A pile of lobsters at the Lewis cannery, Isle au Haut, c. 1870. |

Meanwhile concern for the lobster population consistently grew louder during the Lobster Rush, as voiced in two major, separate reports by the Canadians and the Americans in 1873 and 1887.35 As European countries had done, American states and the Canadians began to pass a series of conservation laws, but they were not easily regulated or nearly effective enough. In 1905 naturalist Alfred Goldsborough Mayer admonished: ‘Unless wise laws are soon enforced for their protection the ruthless persecution to which the lobsters have been subjected will practically exterminate them, in so far as commerce is concerned.’36 More humorously and perhaps indicative of public concern, Holman F. Day published a poem in 1900 titled ‘Good-by Lobster’, which ends with this verse:

I see, and sigh in seeing, in some distant, future age

Your varnished shell reposing under glass upon a stage,

The while some pundit lectures on the curios of the past,

And dainty ladies shudder as they gaze on you aghast.

And all the folks that listen will wonder vaguely at

The fact that once lived heathen who could eat a Thing like that.

Ah, that’s the fate you’re facing – but laments are all in vain

– Tell the dodo that you saw us when you lived down here in Maine.37

In 1915 our lobster expert Francis Herrick stood before the committee on fisheries in the Maine state legislature. He sounded the alarm of still worse times to come and argued for a maximum size limit to protect large females and all the eggs they produce. Herrick declared: ‘The conservation of the lobster fishery is a purely economic problem, and if we strive to solve it upon the grounds of political bias or personal gain, we shall assuredly fail.’38

At least in terms of recorded landings, lobster populations in North America stabilized as regulations were added and enforced, but did not approach the tonnage of the nineteenth century. It was not until the 1940s that lobster landings increased significantly again, then absolutely exploded in the late 1980s. No one knows the exact cause for this unprecedented rise, seen in no other lobster fishery – or barely any fishery – but theories abound. Anne Hayden and Philip Conkling, frequent writers on the marine policy of the area, wrote: ‘There’s a saying in the region: ask two lobstermen why there are so many lobsters in [Penobscot Bay], and you get three different answers.’39 The same could be said for biologists. And policy makers.

Hayden co-authors a column for National Fisherman and has been involved in local fisheries issues for over twenty years. She told me: ‘I’ve been accused of being obsessed with lobsters. But mostly by my family who are sick of hearing about them – though not sick of eating them for dinner.’40 Hayden explains that landings do not always indicate the health of a population, but there are a variety of theories beyond an increase of effort as to why the lobster catches have skyrocketed in the Gulf of Maine. Predation by groundfish, such as cod and haddock, decreased due to overfishing of those species. In some areas a vigorous urchin fishery, fuelled by Japanese demand, cleared the sea floor of these herbivores, allowing an increased growth of coastal seaweeds, which gave more safe habitat for moulting lobsters. Subtle changes in water temperature and currents might have favoured reproduction. There may be an ‘aquaculture effect’, in which there are simply so many lobster traps in the water that the lobsters are actually being raised and fed until they get to legal size. In addition the coast of Maine and the Maritimes, in contrast to that of Long Island Sound and parts of Europe, has been less developed by industry and residential construction. Their waters are cleaner. Yet none of these arguments alone can explain it all. Hayden says that even the biological premise for shaping policy – the most basic logic that the more eggs there are in the water, the more lobsters there will be – doesn’t receive much credence any more.41

Conservation and enforcement measures put in place seem to have helped, but state officials and the Coast Guard are unable to patrol every harbour and cannot, for example, make sure every fisherman isn’t picking the meat from ‘shorts’ or scrubbing the eggs off legal-sized females. What seems to be different in Maine, for example, in comparison to the lobster industry in Long Island Sound or that of Brazil, has been voiced by anthropologist and economist Jim Acheson, who writes that regulations have not only been accepted and formed by local lobstermen, they are enforced by them. This lobster fishery has climbed out of a get-all-the-bugs-before-the-other-guy-does mentality, a ‘tragedy of the commons’ scenario. Those that do not observe the local rules are punished by their peers. It works, but it can get violent at times. In the summer of 2009 lobster-men sunk three of their competitors’ boats at the dock in Owl’s Head Harbor. Out on remote Matinicus Island, one lobsterman shot another in the neck, in part over territory. The man lived. Months later the lobsterman with the gun was acquitted with a self-defence plea.

Meanwhile, as the landings of Homarus americanus have steadily increased, scientists and environmentalists have consistently predicted a devastating crash. In 1973 Luis Marden in National Geographic worried that ‘this delectable gift from the sea is in danger of disappearing, not from the bed of the ocean, perhaps, but quite possibly from our tables’.42 Steven Murawski, a biologist at the National Marine Fisheries Service, said in 1988 that ‘there’s no way in God’s green earth that these catches could be sustainable’.43 The Monterey Bay Aquarium’s ‘Seafood Watch’ guide, one created specifically for the North-east of the United States, does not even list American lobsters as one of their ‘best choices’ in 2010, recommending instead spiny lobsters flown in from Florida or California. They list Homarus americanus only as a ‘good alternative’.44 Ironically, they use an illustration of the American lobster on the cover of this guide. (One concern of theirs is the threat of lobster gear to severely endangered whales.)

Working in a lobster cannery in New Brunswick, Canada, 1959. Women have been a large part of the workforce in lobster canneries since the 19th century. |

If anything there are actually too many lobsters in the waters of Maine and the Maritimes, at least in terms of the market. Canadians have invested a great deal in developing the ability to process lobsters: frozen tails and a whole range of products. These Canadian companies buy up the lobster caught by Canadian and American fishermen when they can’t sell it in their local markets, then the companies store it in sprawling facilities. The Canadian companies sell their processed lobster all year round to the US, Europe and Asia. They supply casinos, cruise ships and seafood chain restaurants such as Red Lobster. They have even found a pharmaceutical and biomedical demand for the vast numbers of previously discarded shells, which includes use in wound-care products and surgical drapes.

A young man holding a large Caribbean spiny lobster off Mona Island, Puerto Rico, 1997. |

Canadian fishermen consistently catch millions more bugs than US lobstermen. The ‘Maine’ lobsters shipped around the world are often from Canadian fishermen, and when you order lobster tails, lobster linguini or lobster sushi at a restaurant, whether in London, Moscow, Chicago or Tokyo, you might very well be getting spiny or slipper lobster meat – which, to most palates, is by no means inferior – though to others, notably Alexandre Dumas in 1870, ‘the spiny lobster is not so finely flavoured and not so highly prized’.45

Just as sailing vessels once opened up markets for Norwegian lobstermen and canning once opened up markets for trap fishermen in Nova Scotia, freezing technology and air shipping has probably done more to affect world lobster populations and lobster fisheries than any advancement in fishing gear or strategy of management. The ability to freeze and ship to match international demand expanded trade for fishermen in areas rich in spiny lobsters, such as Western Australia and Brazil, allowing them to compete with clawed lobster fishermen. High prices from tourists and the opportunity to sell to lucrative foreign markets encouraged small artisan spiny and slipper lobster fishermen in remote areas in the Caribbean and across the southern hemisphere to fish once pristine coastlines all too thoroughly. Some of these newer fisheries are in it for the long haul, however, hoping not to replicate historical boom and bust patterns. The spiny fishery off New Zealand (mostly Jasus edwardsii), for example, has a progressive individual transferable quota system that seems to be working well in terms of both stocks and fishermen’s profit.

To illustrate the global nature of the lobster as a luxury international commodity, I can tell you that I recently went to Pike’s Place Market in Seattle on a Sunday morning in February. Displayed in ice in front of the men throwing salmon were four gigantic spiny lobster tails. ‘We get them from all over’, the fishmonger said. ‘These? Just came in this morning. From the Dominican Republic. We make a killing before Valentine’s Day. All the guys want to impress their dates. “Lobster”, they say. “Get me some lobster!”’46