Two Major Challenges to the A Priori

This chapter speaks to two crucial ways in which developments in twentieth-century philosophy of language have altered the terrain, when it comes to a priority and the interrelations between metaphysics, semantics, and epistemology. We might think of these as the legacies of Quine and of Kripke, respectively—at the risk of doing a disservice to many of the others (cf. notes 1, 7) who did original and seminal work on these issues. They are the challenge of revisability and the externalist challenge, and they play a monumental role in my development of my preferred variant of the constitutive a priori.

The challenges are introduced and elaborated in §§5.1 and 5.3; and the work of absorbing the shock to the traditional world-order which they pose is begun in §§5.2 and 5.4, respectively, and further developed throughout the rest of Parts III and IV.

§5.1: Quine and the challenge of revisability

A longstanding, central plank of Quine’s naturalistic campaign against immunity to counterexample is the idea that all human claims to knowledge are revisable.1 Quine (1951: §6) is the classic statement of this viewpoint—containing such bold claims as ‘no statement is immune to revision,’ and that even revising the laws of logic would be ‘[no different] in principle [from] the shift whereby Kepler superseded Ptolemy, or Einstein Newton, or Darwin Aristotle’.

Looking back over the course of history, the claim that all beliefs are revisable looks to be fairly well supported. There is a large body of literature on the notion of a scientific revolution, and on the impacts of this concept within our pertinent fields of epistemology and semantics.2 For some examples, that space is Euclidean, that whales are fish, that there can be no such thing as a sub-atomic particle (since ‘smallest, indivisible’ was originally part of the meaning of ‘atom’), etc., were all once considered to be justified a priori (and analytically true), but are no longer so-classified; and it is hard to see how to conclusively rule out such a change in status of our beliefs. The question is what this challenge of revisability entails, for the core ancient notions of metaphysical, semantic, and epistemic immunity to counterexample.

For starters, I will briefly characterize three general lines of response to this challenge of revisability, which I will call ‘skepticism,’ ‘absolutism,’ and ‘revisionism.’ Modal skeptics follow Quine (1951) in holding that the challenge of revisability shows that analyticity, first and foremost, as well as necessity and a priority in its wake, is outmoded and untenable. The web of belief is seamless (to borrow Quine’s metaphor); all beliefs are subject to refutation and replacement. (Cf. Devitt [2011] for an illustrative recent statement of modal skepticism.) As we will see, the skeptic’s biggest problem is the original adequacy objection to radical empiricism—that is, the brute datum (of seeming immunity to counterexample) will not go away. (We are not about to be black-swanned by pentagonal squares, or by ever-childless grandmothers. It is a main aim of the work which follows to dig into the difference between atoms and whales, on the one hand, and squares and grandmothers on the other. About what, then, are we potentially black-swannable? Cf. especially §§5.4, 6.2, and 6.5.)

Modal absolutists dig in their heels and insist that immunity to recalcitrant experience is a central core component of an adequate epistemology; so to hold that (say) a priority is revisable is to change the subject. Frege (1884: 3) gives colorful expression to the absolutists’ creed: ‘An a priori error is thus as complete a nonsense as, say, a blue concept.’ Modal absolutism is a central plank in the traditional canon—for example, the view that knowledge of necessary truths can only be justified a priori, which is explicitly endorsed by Kant (1781: [B15]) among many others, depends upon this presumption that there is some supernatural potency about the a priori. However, absolutists must claim that these putative revisability-cases are actually cases in which one just mistakenly thought that one’s belief (e.g., about Euclidean geometry, atoms, or whales) was justified a priori. Among the problems with this option is that these notions (of a priority, analyticity, etc.) become only reliably useful for infallible agents, because agents like us could never conclusively establish the claim that something is justified a priori or analytically true. Thus, the absolutists’ notions of a priority and analyticity would be ill-suited to much work in epistemology or semantics. In any case, most contemporary theorists seem to be wary of modal absolutism—for example, it is explicitly considered and rejected by BonJour (1998: Ch. 4), Field (2000), Peacocke & Boghossian (2000), Railton (2000), and Casullo (2003: Ch. 2). In short, even if the challenge of revisability does not suffice to support modal skepticism, it does amount to a rather strong case against modal absolutism. (Cf. the discussions of fallibilism and the defeasibility requirement, with respect to a priority, in §§4.1–2.)

Modal revisionists side with Pap (1946), Carnap (1950) and others against both the skeptics and the absolutists, in retaining immunity to counterexample but admitting that it is in some sense framework-relative. According to both Coffa (1991: Ch.10) and Friedman (2000: 370), the first clear articulation of revisionism occurs in Reichenbach (1920). Reichenbach alleges that Kant uses ‘a priori’ in two distinct senses—on the one hand, to mean necessary and eternal, and on the other hand, to mean constitutive of the concept of the object of knowledge—and goes on to argue that a moral of the theory of relativity is that the former be dropped while the latter retained. Revisionism seeks to define a principled middle ground between absolutism and skepticism about a priori justification, based on this notion of the constitutive but non-absolute a priori. The revisionists’ response to the challenge of revisability (for the core case of epistemic impunity) is to retain the concept of a priority, in many central senses of the term, while explicitly rejecting certain other of its traditional associations (such as necessity or infallibility). In addition to Carnap’s (1950) linguistic frameworks, this tack on the a priori is also widely associated with Wittgenstein (1921, 1953, 1969). Much interesting and challenging recent work on the a priori consists of variations on this revisionist theme—cf., for example, Friedman (2000, 2011), Railton (2000, 2003), Stump (2003, 2015).3

One important point to register at this stage is that my orientation on these issues is decidedly revisionist. The constitutive a priori view developed here is explicitly fashioned as a development within that tradition. Another is that, given the crucial differences between metaphysical necessity, analytic truth, and a priori knowledge, we should be open to the possibility that the appropriate responses to the challenge of revisability are relevantly different, among these three cases. This is one of many (connected) respects in which a gulf opens up between metaphysical modality on the one hand, and semantic and epistemic cases on the other. In particular, a sophisticated grasp of the ways in which analytic truth and a priori knowledge should be understood as revisable will be crucial, when it comes to refining our understanding of such notions. In contrast, metaphysical necessity is coldly indifferent to the challenge of revisability. (This particular motif has come up in both Parts I and II, and will be further developed as our story proceeds.)

Now to tie absolutism, skepticism, and revisionism to Plato’s problem (i.e., that human experience is finite and limited, and yet we seem to attain some knowledge which is universal and general). Absolutism strikes me as singing loudly and proudly on the decks of the sinking Titanic, on this front. (I admire their audacity, but cannot square with their commitments.) Its current unpopularity is well-deserved. Skepticism, on the other hand, throws out the baby with the bathwater. Sure, things are difficult, when it comes to hard principled work on immunity to counterexample; but there is still the noble goal of an adequate epistemology, and the brute data, to be accommodated. Wouldn’t it be nice if there were a viable tertium quid, between absolutism and skepticism, on the challenge of revisability? Is there a better alternative in the face of Plato’s problem, than the absolutists’ mere declaration of victory, and the skeptics’ concession of defeat?

The aim of the rest of the book is to build exactly that, out of the ingredients cultivated in Parts I and II.

[§]

I am inclined to concede to the skeptics that the challenge of revisability shows up the untenability of modal absolutism. However, the move from here to a naturalism or skepticism pays an important price, and a price which need not be paid at that. For even if the challenge of reviseability amounts to a considerable case again absolutism, it does not amount to nearly as strong a case in favor of skepticism. What is this high price, exactly, then, and how would a non-absolutist go about not paying it?

The high price is, essentially, the ancient adequacy objection to empiricism, or all of the considerable reasons to posit a priority in the first place. The intuitive, principled difference between ‘all swans are black’ and ‘all squares are four-sided’ must be foregone. In other words, the price is precisely the notion of immunity to counterexample.

At a bit more length, modal skeptics must forgo belief in a privileged, constitutive connection between understanding and justification. To illustrate, compare the following pair (which we contrasted back in §4.1):

[1] Squares have four sides.

[2] Neptune has four moons.

For both cases, grasp of the meanings of the constituent bits affords an understanding of what would have to be the case for the sentence to express a truth. However, for the case of [1], grasp of the meanings also and thereby justifies the belief that what it expresses is true. Not so for [2], in which case understanding it does not come remotely close to providing justification for believing that what it expresses is true. Even though I know exactly what [2] means, I have no idea as to whether or not it is true; whereas it is far from clear that a correlative claim could coherently be made about [1]. Hence, [1] is a candidate example of this privileged connection between understandingand justification: To understand [1] is thereby to be justified in believing it to be true.

This connection between understanding and justification is quite central to philosophy, both historically and conceptually—and especially to those orientations which take an understanding-based approach to a priority. Indeed, on some conceptions of the discipline, it is the very essence of philosophy as distinct from other theoretical enterprises; and so, for example, Anselm’s ontological argument, Descartes’ cogito, and Kant’s synthetic a priori are all instances of, or variants on, this general strategy of yielding justification from understanding. (However, the [UJ] connection is perhaps most strongly evident in the case of logical truths. This will be extensively discussed below §6.2.) Hence this price that the skeptic pays is quite high, with repercussions rippling from this corner of epistemology right through to conceptions of the methodology and subject matter of the discipline itself, as a whole.

Apart from this ‘threat of drastic shock’ sort of consideration about rejecting [UJ] connections, what are some positive reasons for keeping it around? What can it buy us?

A lot: these [UJ] connections lie at the heart of any understanding-based approach to a priority (of which the constitutive a priori orientation is an exemplary instance). They are the basis of the link between analyticity and a priority—given that understanding can (in some cases, the boundaries of which are to be limned below) suffice for justification, the resulting set of analytic truths are justified a priori. If there are [UJ] connections, then analyticity can ground (at least some cases of) a priori justification. I’ll call this [UJ] principle 1:

UJP1 will be extensively developed throughout Part III, and will play a role in the maps of the terrain detailed in Part IV. Before that, though, much work needs to be done in terms of showing how the [UJ] connections are to survive the challenges of revisability and externalism.

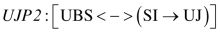

Wherever the relation between semantic intuition and rational intuition has popped up, these [UJ] connections are what we are stalking. These are the cases in which semantic intuition can give all that was wanted, in terms of epistemic justification, from rational intuition. These are the cases in which semantic immunity to counterexample suffices for epistemic immunity to counterexample. So, this is the realm of the un-black-swannable, whose precise contours it is a primary aim of Parts III–IV to chart. The realm of the un-black-swannable is the range of cases in which semantic intuition can underwrite the [UJ] connections, and hence [UJ] principle 2:

So, arguably, nothing less than a non-obscure but adequate epistemology—between absolutism and skepticism—is at stake here.

[§]

The basis of the challenge of revisability, then, is that U (i.e., understanding) seems to be too variable, across times and places, to cement any such firm J (justificatory) foundation. Understanding seems to be relative to various contingent factors. Precisely how the challenge of revisability is to be absorbed, on my orientation, is developed first in the next section, and then charted in the next two chapters. This kind of relativity (i.e., in deep tension with absolutism but a far cry from skepticism) became clearly evident by mid-twentieth century; the varieties of revisionism have blossomed since.

To sum up: Given that modal absolutism is off the table, and that modal skepticism is unwarranted and inadequate, revisionism is a worthwhile research project, and the constitutive a priori is a promising variety of revisionism. The [UJ] connections are worth keeping around for a host of reasons, including especially their promise to ground a non-obscure but adequate stance regarding Plato’s problem.

§5.2: frameworks and the constitutive a priori

The challenge of revisability is that as we humans are fallible and limited, all claims to knowledge seem to be subject to revision over time. Absolutists dismiss the challenge by insisting that such modal notions as analytic truth and a priori knowledge are essentially unrevisable. Skeptics, in contrast, hold that the challenge of revisability shows up as mythical these historically significant ideas of immunity to counterexample. We are now engaged in the task of developing a revisionist response to the challenge of revisability. In particular, this present section will continue the development of my favored response to this challenge, which was described in a preliminary way above in §5.1, and will be developed more extensively below—cf. especially throughout chapter 6.

The core revisionists’ idea is Kantian in spirit, though it self-consciously departs from some elements of Kant’s view. Revisionists seek to define a principled middle ground between absolutism and skepticism, based on this notion of the constitutive but non-absolute a priori. Hence, the revisionists’ response to the challenge of revisability (for the core case of epistemic modality) is to retain the concept of a priority, in many core senses of the term, while explicitly rejecting certain other of its traditional associations (such as necessity or infallibility). There is no entailment from ‘constitutive a priori’ to eternally or necessarily true, though (as we will see) there do remain some clear senses of immunity to counterexample—once the challenge of revisability is properly digested.

For a revisionist, a priority (as well as, relatedly, analyticity) must be understood as relative, in a certain sense—for example, to a linguistic framework for Carnap (1937, 1950), to a language game or world picture for Wittgenstein (1953, 1969), to a theoretical framework in Friedman’s (1992, 2000, 2011) distinctively Kantian take on this same core idea. (I will stick with Carnap’s familiar vocabulary and use the term ‘frameworks.’ My usage is general, such that distinct language games, pictures, theories, etc., constitute different frameworks.) However, this relativity stops well short of modal skepticism (i.e., dismissing the very idea of immunity to counterexample as folly). Such special modal notions as a priority must be understood not as marking off some queer kinds of objects of knowledge, but rather as indicating a special status attached to certain beliefs. To call something a priori is, in part, to say something about the role which it plays in the relevant framework.

Many traditional approaches to a priority regard a priori knowledge as essentially involving a special sort of content (i.e., self-evident grasp of bulletproof superfacts, which glow with luminous certainty). However, proponents of the contingent a priori take a priority to be also essentially a matter of status, not just of content. A priority must be understood not as marking off some special kinds of objects of knowledge, but rather as indicating a special role, function, or status attached to certain tenets. To call something a priori is to say something about the role which it plays in the relevant framework. The a posteriori beliefs are those that the agent treats as being subject to the tribunal of experience; the a priori beliefs are subject to a higher court.

Consider, for example, an agent who sincerely avows the universal generalization that every event has a cause. (This is roughly based on an example discussed by Railton [2000: 178].) Further questions might arise as to the precise content and status of this belief—for example, is this a regulative rule for the agent, the so-called ‘principle of sufficient reason’ (i.e., any conceivable event must have a sufficient cause), or is it rather an inductive generalization (i.e., as far as I know, every event observed to date by any credible observer has had a sufficient cause)? One way to tell is to present the agent with a putative counterexample; say, an alleged uncaused event in the quantum void. To the extent that the agent responds with categorical denial—presuming that there has to be a sufficient cause there, whether or not anyone has yet detected it—that indicates that this particular belief is an a priori regulative rule. If, in contrast, the agent is willing to defer to scientific experts on the matter, and to withdraw or qualify the original universal generalization, then that shows that it was all along an a posteriori inductive generalization. Thus, ‘a priori’ does not simply apply to the content of a belief, but, rather, also has essentially to do with its status, or its place in the relevant, operative framework.

To cite a couple of examples from Carnap (1950), that there are numbers is a constitutive a priori principle of the framework of elementary arithmetic, and that there are ordinary physical objects is a constitutive a priori principle of the framework of folk physics. Considered internally, from within the frameworks, such principles have the status of immunity to counterexample—they are treated as simply not being subject to empirical disconfirmation. They are rather constituent elements of the rules of the game, without which various pertinent sorts of questions could not be asked, or conjectures could not be tested.4 Carnap proceeds from this point to dismiss many traditional philosophical questions—for example, ‘Yes, but do numbers, or physical objects, really exist mind-independently?’—as mistaken pseudo-questions, conflations of the crucial distinction between internal questions (within the framework) and external questions (about the framework). However, while modal revisionism is essentially allied with this Carnapian (neo-Kantian) notion of the framework-relative constitutive a priori, it need not take on any such positivistic meta-philosophical theses.

And note well the clear sense of revisability here. Framework-relative a priority does not involve Platonic, supernatural grasp of luminously certain, eternal superfacts. The frameworks of mathematics and of folk physics do evolve over time, with the attendant corollary that which principles get treated as having this status of immunity to counterexample—as conditions for the possibility of asking clear questions and posing testable hypothesis—also change over time. For example, it was once justified a priori that negative numbers have no square root (for empirical investigation was not required for, or even relevant to, establishing that the product of no number times itself could be a negative number). However, our current framework now includes as an axiom that the imaginary number i is the square root of −1. And note (cf. note 4) that the introduction of i is not smoothly analogous to the discovery of another previously unknown moon orbiting Neptune. It rather constituted a change in the rules of the game.

Further illustrations of the modal revisionists’ notion of a constitutive a priori, as well as arguments in favor of the indispensability of the notion in accounting for scientific progress (contra a prevalent brand of holistic, Quinean, anti-a priori naturalism) are assembled by Pap (1946, 1958), Friedman (1992, 2000, 2001) and Stump (2003, 2011, 2015), among others.5 Pap’s (1946) driving idea is that every scientific theory is built on fundamental principles which must be treated as unassailable for the purposes of framing hypotheses, but nonetheless which principles are treated as having such a status (can, should, and do) change over time. Friedman (2000) develops some specific examples along this vein in considerable detail. For example, in the case of Newton’s scientific advances, certain principles underlying the calculus have to be treated as a priori in order to even formulate, let alone test, Newton’s laws of motion; and, in turn, Newton’s theory of gravitation could not even be intelligibly formulated without taking the laws of motion as a priori, as not subject to empirical disconfirmation. Friedman (2000: 377) describes the epistemological upshot of such episodes in the history of scientific progress thus:

What characterizes the distinguished elements of our theories is … their special constitutive function: the function of making the precise mathematical formulation and empirical application of the theories in question first possible.

This is the heart of the notion of a priority, for a modal revisionist. Beliefs that have the status of a priority are those which play a certain kind of structuring, regulative role in the framework. They are those that are treated by the relevant agent (or community) as being immune to empirical counterexample.

This move from taking a priority to subcategorize the alleged special kind of content of certain special propositions to taking it to be, at least in part, a question of status, function, or role within a framework, is one core pillar shared by all constitutive a priori views. Another is the notion that something must be treated as having this special status in order to get any intelligible inquiry up and running. In order to clearly pose precise, intelligible questions—to isolate variables for testing—some things need to be treated as immune to empirical counterexample. (Examples will be developed below, especially at §§6.1–3, to illustrate some of these generalities.) Such things are thereby constitutive of the framework of inquiry. Frameworks can and do change over time; and there are mundane cases in which multiple distinct frameworks are brought to bear on a particular problem. Nonetheless, in any specific case, there have to be some things with this status of immunity to counterexample to constitute a framework which can then be applied in inquiry.

So, whereas the absolutist treats a priori knowledge as essentially involving a special sort of content (i.e., self-evident grasp of superfacts, which glow with luminous certainty), for the revisionist a priority is also a matter of status, not just of content. A priori knowledge is revisable, on this orientation; though to make such a revision is a much more drastic matter than revising beliefs that lack this status. To revise the a priori is to change the framework (or language game, theory, etc.).

The exact nature of this constitutive a priori varies among the varieties of revisionism—for the Wittgensteinians, the crucial distinction is that between rules and propositions (i.e., between the rules of the game and the moves which may be made according to those rules); for the Carnapians, the key distinction is between the pragmatic and conventional criteria which define a framework and the things which then become sayable or decidable within that framework; etc. (Much more on this in §6.1.) And note well that this is not merely a bifurcated, twofold distinction. Frameworks are often re-evaluated, revised and updated, in more or less drastic ways; we often encounter complex situations to which multiple distinct frameworks may be simultaneously applicable, and the relations between these distinct frameworks can be multi-faceted and dynamic. Conceptual evolution can only be framed as a neat narrative in hindsight.

It is a main order of business in chapter 6 to mine and sort these kinds of complexities. (See also §5.4 for discussion of some crucially different kinds of framework.) Across the diverse spectrum of distinct kinds of framework—from agriculture to cosmology, from meta-ethics to mathematics—the particular balance between internal and external questions may well vary widely, as may the sorts of considerations which matter when it comes to engaging with both sorts of questions.

Note also that, even despite this stress on status as opposed to just content, obviously not all contents are equally suited to such a status. For example, in §6.2 I will argue that &-elimination is much better suited for a priority than the law of excluded middle; and examples of contents mistakenly treated by others as being immune to counterexample are not hard to find (e.g., ‘White males are intellectually superior,’ ‘Bad things happen in threes,’ ‘All that happens is for the best, because it is God’s will’). The evaluation of frameworks as more or less reasonable, based on differences among the contents which are taken to be a priori, has clear appeal both within and beyond its promise to help make sense of the notion of scientific, political, and philosophical progress.

In any case, getting back to [UJ] connections, the core idea here is that a priority (which includes our focal notion of logical truth as a distinctive sub-case) should be understood not as marking off some queer kinds of objects of knowledge, but rather as indicating a special status attached to certain basic tenets. To call something a priori is to make a claim about the kind of basic, structuring, regulative role which it plays in the relevant framework. So note that this kind of revisionism in general is allied with an understanding-based, as opposed to an acquaintance-based, approach to a priority.

This notion of a framework, and its relevance to the challenge of revisability, among many other things, will be further elaborated below. My constitutive a priori variant of modal revisionism holds that there is immunity to counterexample but it is framework-relative. I will continue to build the case that that is the best way forward from this challenge, all things considered, for grounding a non-obscure but adequate answer to Plato’s problem.

§5.3: Kripke and the externalist challenge

We begin our engagement with the externalist challenge with a quick trip back to some basic notions from Part I (especially §2.3), to set things up. For the externalist challenge affects precisely the relations between meaning and extension; which thus problematizes considerably the notions of semantic and epistemic immunity to counterexample, and their relations to metaphysical necessity. When it comes to the core [UJ] connections and principles, at the heart of any understanding-based approach to a priority: this potential blockage between meaning and extension threatens to undermine whether U (understanding) can supply anything remotely like J (justification); and so thereby whether semantic intuition can be relied on for anything substantive in epistemology.

Hence, in addition to the challenge of revisability, and dovetailing with it in many respects, the externalist challenge too threatens to undermine the core [UJ] connections. In general, Part III is all about saving [UJ]—and so what semantic intuition and understanding-based accounts of a priority can do for Plato’s problem—from the two-pronged assault which I am associating with Quine and Kripke.

I will use the term ‘traditional internalism’ to designate a certain conception of the relation between meaning and extension, which went virtually unchallenged until well into the twentieth century. Canonical sources which state clear allegiance to this orthodoxy include Plato (1928b: 324A–343A) and Locke (1690: Bk 3, I–III). These presumptions are guiding principles in seminal work in the philosophy of language by Mill (1843), Frege (1892), and Russell (1918), and are explicitly defended as recently as Strawson (1959) and Searle (1969).

Details differ, but the general internalist picture is this: every term is semantically associated with a meaning which specifies the conditions for membership in the term’s extension. Competence with a term is a matter of associating it with the appropriate meaning, which is made manifest by the agent’s ability to distinguish the extension from the anti-extension (in normal contexts). On the traditional view, the criteria for the correct application of a term are introspectively available to competent agents.6 These criteria for correct application, and hence the content of the propositions expressed by their utterances, are completely transparent to individual agents—there is nothing hidden from view, no reason why we would have to invoke something external to an agent in order to individuate the contents expressed or entertained. Individual agents who are semantically competent are autonomous as to the conditions that determine the extensions of their terms.

Wittgenstein (1953) is one influential critic of this traditional internalism. He points out that while most of us are rather good at distinguishing the extension from the anti-extension of the term ‘game,’ for example, we are rather horrible at articulating any meaning that specifies what all and only games have in common. Wittgenstein is also thoroughly critical of the presumption of first-person authority about meaning, insisting rather that the criteria for the correct application of terms crucially depends on the practices of a community. Strawson (1959) and Searle (1969) both attempt to accommodate some of Wittgenstein’s insights, within general internalist confines.

Another forceful challenge to the traditional orthodoxy comes in the 1970s (though it was certainly influenced by Wittgenstein, among others).7 Consider, for example, an agent who associates with the name ‘Columbus’ the inaccurate meaning ‘the first European to sail to North America,’ or who associates with the name ‘Einstein’ the vague meaning ‘a famous physicist.’ First, Kripke points out that these sorts of cases are fairly common, much more representative than the small handful of tendentious examples discussed within the traditional orthodox literature (e.g., ‘Bismarck’ means ‘the first Chancellor of the German empire’). Second, Kripke motivates the claim that such speakers nonetheless count as competent with these terms—they are able to participate in the interchange of information about Columbus and Einstein—despite not having any introspective grasp of the conditions for the term’s correct application. (The agent knows nothing to distinguish Einstein from Heisenberg or Feynman, and the condition associated with ‘Columbus’ probably picks out some ninth-century Viking.) Third, Kripke argues that this shows that whatever it is that determines the extension of a use of a term, it must be distinct from the often vague and shoddy information that constitutes the meaning which the speaker associates with it. In general, meaning (i.e., the information which the speaker associates with a term) need not determine extension. The conditions for the correct application of a term need not be accessible to competent speakers.

‘Externalism’ is an apt label for this line of thought in that the upshot seems to be that (at least in some cases) something external to the agent must be invoked in order to determine the extension of the terms they entertain and express. In addition to proper names, the externalist challenge also forcefully applies to natural kind terms. Competence with such terms does not depend on a grasp of the precise criteria for their correct application—even if I couldn’t tell whether some non-typical specimen is or is not a tiger, still I count as competent with the term ‘tiger.’ Prevalent candidates for semantically relevant external factors include: (i) the causal-historical chain of transmission of the expression tokened, (ii) facts about the actual nature of the ambient environment which may be inaccessible to ordinary speakers (e.g., differences between gold versus iron pyrites, H2O versus XYZ), and (iii) the states and doings of certain specific sub-sets of the linguistic community in which the speaker is immersed (such as Putnam’s [1975] ‘experts,’ or Evans’ [1982] ‘producers’).

[§]

I will use the term ‘the externalist gap’ [EG] to denote this phenomenon wherein meaning (i.e., the conditions which competent speakers associate with a term) seems to be distinct from what determines the term’s extension. To say that there is an [EG], for a particular use of a particular expression, is to say (in Kripke’s [1972] terms) that separate answers seem appropriate for what ‘gives the meaning’ versus what ‘fixes the reference.’ Alternatively, we could define the [EG] using Putnam’s (1975: 225) “two [traditionally] unchallenged assumptions”: (i) knowing the meaning of an expression is a matter of being in a certain intrinsic state, and (ii) the meaning of an expression determines its extension. The core of the externalist challenge to traditional internalism is the notion that, in general, nothing can do both jobs (i) and (ii).

Traditional internalism holds that one univocal ‘meaning’ (in a fairly clear sense of that notoriously ambiguous term) is both that the grasp of which constitutes competence, and that which determines extension. (For example, the meaning of ‘triangle’ is something like ‘three-sided closed plane figure’; a grasp of that constitutes competence with the term, and anything that satisfies that counts as a triangle.) The externalist challenge to traditional internalism, then, has it that, in general, no one thing can play both of these roles. For any particular semantic property S: if S is intrinsic to individual speakers, then S does not in general determine reference; and if S determines reference, then S is not in general intrinsic to individual speakers. Putnam (1975: 249–50) puts this point by exploring the ways in which ’the traditional problem of meaning splits into two problems’—that is, ‘determination of extension’ versus ‘describing individual competence’. A more Kripkean (1972) spin would be to criticize Fregeans for using the term ‘sense’ in two distinct senses, and to then develop the distinction between ‘giving the meaning’ and ‘fixing the reference’.

Herein also lies the reference fixer—as distinct from both meaning and extension—discussed above at §§2.3 and 3.2. In cases in which there is an [EG] (i.e., the meaning is distinct from the criteria for membership in the extension) there arise questions as to the nature and workings of the reference fixer. This is a significant aspect of the externalist challenge, and it problematizes precisely the putative transparent relation between meaning and extension—and hence between the U (i.e., what constitutes understanding) and the J (i.e., whether it can amount to justification).

[§]

I will not go further into the exact substance of the externalist challenge to traditional internalism, but rather will take it as commonly known and relatively uncontentious. Along with most, I hold that Donnellan (1970), Kripke (1972), Putnam (1975), Burge (1979), and others have developed a very strong case for an [EG], at least in some cases. (Further, I will take Putnam [1975] on the distinction between (i) and (ii), discussed above, and Kripke [1972] on ‘giving the meaning’ versus ‘fixing the reference,’ to be completely interchangeable ways of articulating this [EG].)

One significant way to divide up varieties of semantic externalism, then, concerns the range of cases which are amenable to this [EG]. To illustrate, a view toward the moderate end of the spectrum of options holds that there is only an [EG] in cases of deferential uses of proper names and natural kind terms (e.g., ‘Feynman is a physicist,’ ‘Molybdenum is a metal,’ said by speakers who would explicitly disavow any ability to distinguish their referents from other physicists or other metals). In contrast, a view toward the opposite extreme holds that the [EG] is applicable to all thought and talk—even to ordinary, competent speakers’ everyday usage of the simplest possible terms (e.g., ‘and,’ ‘hunter,’ ‘bachelor,’ ‘triangle’). In general, there are considerable reasons to be given in favor of both of these extremes, and there are also grounds for lots of principled intermediate views.

I will distinguish three different theses about the range of the [EG]—which I will call the Pragmatic, Semantic, and Metasemantic theses. The Pragmatic thesis takes the [EG] to be a property of certain limited type of linguistic usage; the Semantic thesis takes the [EG] to be a property of certain limited type of linguistic expression; and the Metasemantic thesis takes the [EG] to be a general discovery about the nature of language. By §6.5, I will have assembled the ingredients for an argument for the Pragmatic thesis, and, relatedly, in favor of a relatively moderate semantic externalism. One main aim of chapter 6 is to explain that moderate externalism is how an understanding-based, constitutive a priori approach best absorbs the externalist challenge.

So, to sum up: there is a very strong case for an [EG], at least in some cases, and it is certain to have considerable impact on our maps of the terrain at which epistemology overlaps with semantics and metaphysics. But the proper upshot of this externalist challenge is still somewhat up in the air. Some of the hard work to be done in order to sort this out includes: (a) getting a firm grip on the extent of the externalist challenge—that is, how far beyond the cases of proper names and natural kind terms do these arguments apply?; and (b) getting a better handle on the mechanisms that externalists hold to play a role in determining reference—and in particular on the notion of deference, which plays a critical role in virtually any post-Wittgensteinian theory of reference. Both of these matters are engaged in the considerable depth in chapter 6.

[§]

When it comes to the externalist challenge to traditional conceptions about meaning and extension, so-called ‘incomplete mastery’ cases are centrally at issue—that is, speakers of whom there is considerable reason to count as competent with an expression, but who nonetheless are not able to articulate effective criteria for its correct application, which distinguish the extension from its complement. If incomplete mastery does not entail semantic incompetence, then the ability to fix the reference is not criterial for grasping the meaning. The Wittgensteinian line of thought that some or most of our concepts are not constituted by necessary or sufficient criteria poses one line of challenge to traditional internalism here. But the externalist challenge, while perhaps properly seen as a further step in this same direction, is a more categorical jolt. Regardless of what one thinks about exactly how to characterize some or most of our concepts, externalists argue that what matters for competence and what determines the reference are generally distinct sorts of question, the answers to which involve rather different sorts of considerations.

When it comes to natural kind terms, for which the case for a division of linguistic labor is especially strong, the intuition that incomplete mastery is compatible with competence is fairly robust. We are content to count Kripke as competent with ‘tiger’ even though he might not be able to say of some non-typical specimen whether or not it ought to be classified as among the tigers, and to count Putnam as competent with ‘gold’ even though he is potentially subject to dupe by clever counterfeit. Fair enough, so far. Of course, Putnam (1975: 233) himself points out that ‘some words do not exhibit any division of linguistic labour: “chair,” for example’. (As we will see in §6.5 below, there are passages in Kripke [1972, 1979] which suggest that his externalism is much more moderate than radical.8) Even the move to Putnam’s (1975) ‘beech’/‘elm’ case might be argued to be a difference of kind and not degree—perhaps our community demands more to count as competent with these terms, than merely that they name ‘some kind of tree’.

Things get shakier still with, say, Salmon’s (1989) claim that competence with the terms ‘catsup’ and ‘ketchup’ is compatible with believing that they name distinct condiments. (That is, exactly akin to a Hesperus/Phosphorus case, one could be competent with both ‘ketchup’ and ‘catsup’ while thinking that they name distinct condiments.) Really? REALLY? Competence? I take it that the obvious traditional internalist response—that is, to the contrary, such an agent ipso facto falls short of competence with at least one of these terms—clearly has considerable purchase in this case. It takes some audacity to try to twin-earth up an [EG] for ‘triangle’ (or ‘grandmother,’ ‘fortnight,’ or ‘and,’ to name a few).9

§§6.3–5 will consider these matters closely. For now it suffices to underline that incomplete mastery cases encapsulate what is at issue here, when it comes to differences between internalists and externalists. And so, again, when it comes to the question of the range of the [EG], is the moral that there exist certain distinctive, limited sort of cases in which competence is compatible with incomplete mastery? (In Fregean terms first broached in note 15 of chapter 1, does sense not always determine reference, or rather generally never determine reference?) Or that competence is, quite generally, compatible with incomplete mastery, for any linguistic expression?

A related bone of contention between internalists and externalists concerns the transparency of meaning, or whether typical speakers individually have introspective access to the criteria for the correct application of the expressions with which they are competent. The transparency of meaning was an axiomatic presumption for traditional internalists—one gets a strong whiff of an axiomatic commitment to transparency in reading, say, Russell (1918) or Frege (1892a). (Transparency requires no defense by argument; it is analytically entailed by what ‘meaning’ means! Further, it is crucially presupposed in, for example, the characteristic distinctive inferences which Frege and Russell draw from the informativeness of statements of the form ‘a=b’—in Frege’s case, to a difference in sense between ‘a’ and ‘b’; in Russell’s case, to the conclusion that at least one of ‘a’ and ‘b’ is a description in disguise.) Indeed, it is only once something like Kripke’s (1972) distinction between ‘giving the meaning’ and ‘fixing the reference’ is drawn that failures of transparency for competent speakers become a clearly intelligible possibility. However, most contemporary philosophers take the seminal externalist arguments to have established counterexamples to transparency. (Most but not all—even in the wake of the seminal externalist arguments, we still get Dummett’s [1978: 131] flat assertion that ‘transparency’ is ‘an undeniable feature of linguistic meaning’—the preservation of which intuition is one of the driving motivators for two-dimensional approaches to semantics [cf. Chalmers {2006}].)

Transparency is of course just a metaphor, but an apt one. Given that the meaning fixes the reference, then there is in principle nothing hidden from the view of competent speakers: the light of the individual competent speaker’s mind illumines the boundaries and contours of the extension. The criteria for the correct application of a term are introspectively available to competent agents, who are thus autonomous as to the conditions that determine the reference of their terms, according to this aspect of traditional internalism. One last corollary question, then, probing further into differences between the Pragmatic, Semantic, and Metasemantic theses about the [EG]: Have the seminal externalist arguments shown that the meanings of certain distinctive kinds of expression are not transparent? Or that linguistic meaning, in general, is not transparent?10

[§]

Hence, this externalist challenge is deeply relevant to several core questions about immunity to counterexample, and about the nexus at which the philosophy of language overlaps with metaphysics and epistemology. It also ties in with the challenge of revisability in complex and interesting ways, further complicating the framework-relativity of the U (understanding) aspect of the core [UJ] links and principles. (Quine and Kripke in superposition!) The challenge of revisability strongly suggests that U is historical, perspectival, fleeting, and the externalist challenge threatens to have identified a blockage between U and J.

Revisability first: is anything really immune to counterexample? Here we will have to distinguish between the cases of metaphysical, semantic, and epistemic impunity. Working through this challenge will prompt refinement to their interrelations, to the relation of each to semantic intuition, and ultimately to Plato’s problem.

As for externalism, this prompts much refinement to our understanding of the notions of meaning, extension, reference determiner. It also limits the metaphysical conclusions which could be supported by anything having solely to do with reflection on meaning, content. (Does, or can, grasp of meaning bring anything in its train that is of epistemic or metaphysical import?) This is particularly true of questions which pertain to analyticity and a priority—for those notions are, to a large extent, precisely about transparent access to a certain sort of truth or knowledge. The externalist challenge (to the connections between meanings and extensions) threatens to undermine that access. Immunity to what, and if so how?

The two challenges dovetail in that the gulf between analyticity and a priority on the one hand, and necessity on the other side which is required to answer revisability—which has been a recurring motif since the latter pages of chapter 1—is also a moral of the externalist challenge. Like revisability, externalism also affects discourse about mind matters and language matters of metaphysics differently than it affects discourse involving categories which humans construct rather than discover. We will now dive headlong into this chasm.

§5.4: no statement is true but reality makes it so

Framework-relative modal revisionism will be my answer to the challenge of revisability, as developed on an understanding-based constitutive a priori orientation. What, similarly, answers the externalist challenge? One crucial part of the answer concerns principled differences between different kinds of frameworks, and the different mechanics appropriate across this divide, when it comes to relations between meanings and extensions.

We saw in §4.3 that Quine’s flat-footed insistence that ‘No statement is true but reality makes it so’ has played a role in shaping various pictures of modal space. This present section continues the work started there, in terms of honing and refining what that crude dictum might mean, and what consequences it should have. Perhaps the most important present point is that if this tenet is to be upheld, then it is crucial to distinguish between certain different kinds, or aspects, of reality. This is an important step in a satisfactory, refined response to the externalist challenge. Generally, this present section is going to unpack some material that chapter 6 is going to then spread out and develop.

A key point is that Quine’s dictum is going to apply rather variously, across different kinds of frameworks. Consider for example the different ways in which ‘No statement is true but reality makes it so’ apply to, or impose constraints on, ‘Aluminum is a metal’ versus ‘Widows are formerly married women whose spouse has died.’ Only the former targets and makes a judgment about mind-independent reality; the latter does something more like categorize something which is presupposed rather than judged upon. Non-empirical access to the ‘facts’ or ‘reality’ at stake here are really quite drastically different matters (i.e., access to the categories themselves versus access to what is intended to be categorized). So, given the huge differences between the kinds of concept that ‘aluminum’ and ‘widow’ are, questions about a priority and the externalist challenge are going to apply rather diversely to them. (Compare the different senses of ‘factual’ discerned in §4.3.)

Conventionalism (i.e., roughly, human convention is the source of what otherwise might seem to be metaphysical necessity) may not be an adequate approach to all immunity to counterexample, but it still might be the right thing to say about some of it. Human cognitive activity is partly constitutive of reality when it comes to some of our thought and talk. And this will be crucial when it comes to not only the externalist challenge, but also Plato’s problem, and staking out the un-black-swannable turf. (The deep and crucial [EG]—and, relatedly, the varietals of immunity to counterexample—is going to apply rather diversely across this divide among distinct sorts of framework.)

This divide is most directly and explicitly about how to absorb the externalist challenge, though the ways in which it is also pertinent to the challenge of revisability will also be charted. Since this fissure affects the notion of a framework, in fairly deep and far-reaching ways, and frameworks in turn are tied integrally to our responses to both of these challenges, many such considerations apply to both phenomena together.

Recall too the point made in §1.4 above, that one fairly canonical way to divide off the moderate rationalists from the moderate empiricists (who can look rather similar, as both camps agree that there is a priori justification but reject acquaintance-based accounts) concerns whether it is possible to attain a priori knowledge ‘of the world.’ Thus, empiricists would typically toe the Humean line that a priori knowledge is limited in scope to our own ideas or concepts, while the rationalists would espouse a more ambitious and bold conception of the range of a priority. This fissure will be further developed, from this present section and on through what follows. The question of the ampliative potential of semantic intuition will be crucial in general, in developing my constitutive a priori account, and decisive in particular, when it comes to whether that account should be seen as a variety of rationalism or of empiricism.

[§]

To begin, let us distinguish between social-conventional reality and mind- and language-independent reality. (Cf. Cassam [2000] for discussion; he acknowledges Locke and Kant as guiding influences.) Cassam’s (2000: 59) examples of social-conventional phenomena include that January has 31 days, and that suicide is the taking of one’s life. We enjoy a sort of privileged access to social-conventional phenomena, precisely because what grounds these categories, and holds them in place, is our thought and talk. There is no mystery as to how statements about all Januarys having 31 days, or all suicides being the taking of one’s own life, could be knowable a priori because we intentional agents are ourselves co-constructors of the data. There need be nothing remotely supernatural about it. (This might seem to run into tension with the widespread externalist tenet that meanings and concepts are fundamentally the property of a community, not an individual, but stay tuned for the discussion [in §§6.3–5] of transparency, deference, and the limits of semantic externalism.)

In contrast, natural kind terms are the paradigm case of expressions which concern mind- and language-independent phenomena. To use a term as a natural kind term involves a deferential, Lockean, ‘I know not what’ intention. That is, on most typical uses, terms like ‘tiger’ and ‘water’ are used to refer to some mind- and language-independent kind of thing or stuff, the precise criteria of identity for which is typically unbeknownst to speakers who nonetheless count as competent with the term.11 In this case, a priori knowledge would be a different matter entirely. If a speaker’s intention in uttering ‘tiger’ or ‘water’ is this natural kind, deferential, whatever-it-is-exactly-that-constitutes-the-real-essence-of-this, then the speaker does not have the same kind of transparent access to the content expressed by their statements, as they do in the case of social-conventional kinds. So, provided that the term in question is used as a natural kind term, then Kripke’s (1972) essence-identifying, a posteriori necessities can occur (e.g., ‘Gold is the element with atomic number 79’).12

So, when it comes to our thought and talk about natural reality, we can discover surprising necessities, as we learn about essences and laws of nature. Some frameworks do target objective external phenomena, as opposed to conventional categories. A priori knowledge here is a different beast. This is discoverer’s knowledge, as distinct from maker’s knowledge. Such discoveries (about gold, heat, water, and so on) are certainly not a priori or analytic at first, though they can get sedimented into the conceptual fabric of a framework over time. After a vague threshold has been decisively passed, it may become knowable a priori that whales are mammals, or that water is H2O.

In contrast, when it comes to our thought and talk about social or conventional reality, here we have a priori access to the data, which is hardly mysterious or supernatural. Certain of our beliefs about all Januarys, suicides, grandmothers, widows, or bachelors are immune to counterexample, and our justification in such cases has nothing to do with empirical evidence. (Many would want to call such cases non-factual—though, again, compare the discussion of some importantly different senses of the vague term ‘factual’ in §4.3.)

Note that I am not suggesting or insisting that natural reality and social reality are two discrete exclusive monoliths. Some issues surely might fall into both or neither; and non-trivially distinct sub-varieties may be distinguished, within each. (For example, lots of research in psychology might be seen as focused on shades of grey between these extremes.) Just rather that, since there is more than one relevantly different sense of ‘reality,’ when it comes to the relations between our thought and talk and its truth-conditions, this ‘no statement is true but reality makes it so’ slogan needs to be handled with caution.

[§]

There are distinct sorts of frameworks, from chemistry to interior decorating, from politics to logic.13 Social-conventional frameworks do not have an external objective mind-independent target. The relevant categories are constituted by our thought and talk. But natural frameworks are another matter, attempting to target mind- and language-independent desiderata. In the case of natural frameworks, in general, the [EG] between meaning and extension is open, with all that entails. The meaning which any individual or community semantically associates with ‘aluminum’ or ‘water’ may not suffice to determine any specific extension, but it is a different matter entirely to press that kind of case for ‘grandmother’ or ‘fortnight.’

Compare the sense in which the slogan ‘no statement is true but reality makes it so’ applies to each of the following, to get a sense of the fair degree of diversity:

1. Aluminum is a metal.

2. Cats are animals.

3. Pencils are artifacts.

4. Widows are formerly married women whose spouse has died.

5. A fortnight is a period of 14 days.

Here we see a more or less gradual transition from ‘targeting and making a judgement about’ cases, toward ‘categorizing something which is presupposed’ sort of cases. Quine’s dictum might apply to all five, to be sure, though it surely seems to do so in quite different ways to [1] and to [5].

We might also compare the above along a dimension explored by Burge (1979)—that is, openness to correction. (This will be deeply relevant to discussions about the limits of externalism to come in chapter 6.) If scientific consensus were to come to hold that [1] is false, that would be a surprise; but surely we would all fall in line, without much in the way of a shock to the rest of our world-views. (I mean, what do I know, really, about the nature of aluminum or the precise criteria for being classified as a metal?) [4] or [5] simply could not turn out to be false, as I currently use the relevant terms—though such words and concepts are prone to evolve over time. As for something like this:

6. If P and Q, then P.

In this case I have no grasp whatever on the kind of conceptual revolution it would take for me to reject this belief. Hence, these three are ranked in increasing order of resistance to correction. [1] is high on the deferential index but low on transparency; and the moves to [4] and then [6] are moves toward less deference and more transparency.

There is much more on this point, and its consequences, throughout chapter 6. We will come back to this issue and consider its connection to the Metasemantic, Semantic, and Pragmatic theses about the [EG]. The main present point is to introduce a discussion of the different ways in which Quine’s dictum applies here, across a variety of cases. The externalist challenge should be understood to apply differently to different aspects of the lexicon. There are relevant divisions which must be respected between kinds of terms, when it comes to incorporating the effects of the challenge of revisability, in addition the externalist challenge.

[§]

OK, fine, no statement is true but reality makes it so; but distinguishing these crucially different senses of ‘reality’ is essential. Both categories of natural and social reality will admit of interestingly different sub-varieties. Rather than heading down that path right now, though, the pressing ongoing task of Part III is to apply this distinction to the question of the proper morals of the challenges of externalism and revisability, for our ongoing inquiry. Indeed, when it comes to both of these challenges, different morals and refinements are going to be appropriate, across this natural/social reality divide.

This distinction between natural and social reality, in conjunction with the work in §5.2 on frameworks and the constitutive a priori, highlights precisely how and why semantic and epistemic immunity to counterexample survive the challenge of revisability. It is the ever-re-evaluated frameworks that we co-construct, and to which we have non-mysterious, non-empirical access. Constitutive a priori knowledge and analytic truth involving the fabric of such frameworks seems to be both unproblematic and significant. Here, semantic intuition penetrates the veil (and U can reach J), whereas, in the case of natural reality, semantic intuition is subject to potential [EG] blockage (between U and J). We try to fashion our frameworks to track or reflect the nature of things as best we can, and while in retrospect we can see clear progress over time, at any point we cannot be conclusively certain that we have got things right, etc.; in contrast, social reality and our frameworks co-constitute each other. Hence, constitutive a priori knowledge and analytic truth involving social reality seems to be eminently attainable.

Most generally, then, the main aim of Part III is to show how an understanding-based, constitutive a priori orientation is well-equipped to absorb the challenges of revisability and externalism, and to afford an adequate, non-obscure answer to Plato’s problem. The more specific business of this chapter has been to lay out those challenges, and to begin to develop, first, the modal revisionist response to the former and, second, the moderate externalist response to the latter. The [UJ] connections form the spine of this orientation, and the [UJ] principles capture their fundamental relevance to Plato’s problem.

NOTES

1. In addition to Quine, other leading figures in work pertaining to the challenge of revisability include Mates (1950), White (1950), and Goodman (1952). A more general epistemic fallibilism of course long predates this period, dating back to ancient skepticism. More proximate influences for this above work can be found in Pierce and Dewey.

2. Kuhn (1964) is a classic early discussion; Friedman (2001) and Stump (2015) are more recent treatments which are more explicitly along the rails of a constitutive a priori orientation.

3. Cf. p.iv of the Preface for an overview of constitutive a priori views; and §6.1 for an in-depth look at three instances. Field (2000, 2005) provides an example of modal revisionism which is not a constitutive a priori view (at least not explicitly, though it is consistent with one, as we will discuss in §6.3).

4. The influence here of Wittenstein (1921) is palpable. Consider 5.473 ‘In a certain sense, we cannot make mistakes in logic,’ 5.4731: ‘What makes logic a priori is the impossibility of illogical thought’. Certain axioms are conditions for the possibility of intelligible discourse; to change them is to change the framework of discourse itself. (Alternatively, compare what it would be like to give up on the following two beliefs—‘Neptune has four moons’ versus ‘Squares have four sides’. The former would be easy and relatively inconsequential, but the latter would involve a change of framework. The meaning of ‘Neptune’ would preserve unscathed, but not so for ‘square’!)

5. Even Maddy (2000: 109–10) throws in a couple of nice anti-Quinean, pro-revisionist cases, despite her self-styling as a Quinean naturalist. More on this in §6.3.

6. This has to be qualified in order to apply to Strawson (1959), and to any other traditional view which attempts to accommodate reference-borrowing (i.e., in which a speaker intends to exploit what others know instead of presuming an autonomous connection to the referent). However, Strawson still belongs within the traditional camp, since on his view reference-borrowing just passes the buck to some other agent. That is, Strawson’s view is that the traditional constraints need not apply to every single utterance; whereas (as we will see) Kripke’s view is that the traditional constraints are deeply misguided. (Cf. Kripke [1972: 90–92] for discussion of Strawson’s view, and Kripke [1986] for related discussion.)

7. Kripke (1972) is the most thorough and influential source here. Other important contributions include Donnellan (1970), Putnam (1975), Burge (1979), and Kaplan (1989). For recent overviews of semantic externalism, cf. Gertler (2012), Kallestrup (2012).

8. I am tempted to say this of Burge too, based on his criticisms of certain kinds of move which (as we will see below) are key to the Metasemantic thesis—cf. e.g., (2007: especially pp. 157, 160–61). However, Burge is primarily concerned with the mental, not the linguistic. So while lots of Burge (1979, 1986, 2007) obviously has deep relevance to some of these issues—to cite just one other example, Burge’s (1979) work on the significance of how the agent would respond to correction is crucial for my case in favor of the Pragmatic thesis—still I am reluctant to try to tie his anti-individualism about psychological content to any particular position on the spectrum which I draw herein, pertaining to the range of the [EG].

9. Philosophers are of course not known for their lack of audacity—cf. Williamson (2006, 2008—especially 2008: 95–96) for an attempt in the case of ‘and’, and Boghossin (2011), Sullivan (2015b), for responses. This issue is discussed in depth in §6.2.

10. The [EG] and the reference determiner are interdefinable—there is an [EG] iff there is need to posit a reference determiner, as distinct from both meaning and extension. So, both may be seen as labels for what is involved when transparency fails. (That the reference determiner is distinct from the meaning is that Frege’s [1892a] telescope is occluded, perhaps better characterized as a kaleidoscope rather than a telescope. What we have transparent access to may not limn or shadow anything beyond the bounds of our concepts.)

11. There are of course lots of non-typical uses of these terms (as of any other). Consider, for example, Chomsky’s (1993, among other places) pessimism about the externalist tenet that H2O is the essence of water, on the grounds that what counts as water in lots of places is a lot less purely H2O than Sprite or tea is. Such uses of ‘water’ are not uses as deferential, essence-targeting natural kind terms, but rather uses as practical kind terms (i.e., ‘whatever it is that flows out of this tap’). Cf. below §6.4, especially note 18.

12. See Sullivan (2003b, 2012) for discussion of the notion of deference at work here. It will also be further developed below, especially in §6.4.

13. There are parallels between this fissure between natural versus conventional frameworks and the ever-present realism versus constructivism debates. Realism is to natural reality what constructivism is to conventional reality. Realists are at their most realist when it comes to unspoiled, pre-categorized nature; whereas constructivists take the cognitive activity of categorization to co-construct and constitute reality.