The Scots did not think Samuel Johnson was so cute when he defined oats in his dictionary as “a grain which in England is generally given to horses but in Scotland supports the people.” A snide remark Johnson may have intended, but he was actually paying the Scots a high compliment. They had not only discovered a food very high in nutrition and very low in cost of production, but one that grew well in their climate. The first commandment of the wise garden farmer is to learn how to make good food out of what grows well in one’s own climate.

Of all the cereal grains, oats ranks highest in protein and runs neck and neck with wheat as the all-around most nutritive cereal grain. And as everyone knows now, oats are considered to be particularly helpful in lowering cholesterol. The 1950 USDA handbook on grains rates oats at 14.5 percent protein, while whole wheat runs second with 13.4 percent. These figures are somewhat outdated now, especially in regard to oats. The average of 287 varieties selected from the World Oat Collection recently averaged 17 percent in protein content. More significantly, new varieties are constantly raising the protein ante to as high as 22 percent on a dry basis. That could make oats almost competitive with soybeans in terms of protein (soybeans contain about 35 percent protein but yield less per acre than oats).

Most plant scientists express belief in a bright future for oats as human food. Part of their reasoning is based on the character as well as the quality of oat protein. It has a bland taste, is soluble under acidic conditions, is stable in emulsions with water and fat, and holds moisture, thus making it an ideal protein to supplement other foods. At the USDA laboratory in Peoria, Illinois, researchers are using oat protein to make nutritious refreshment beverages, meat extenders, and high-protein baked goods.

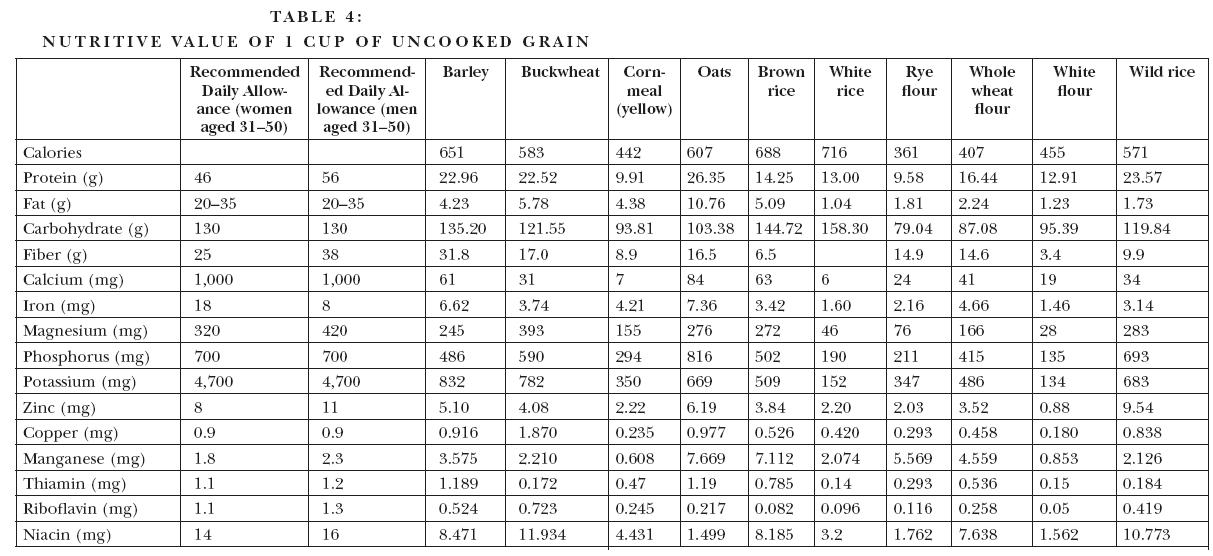

Oats also outscore other cereal grains in thiamine, calcium, iron, and some say, phosphorus, though the USDA tables from 1950 in table 4 give whole wheat a slight edge in that department. Whatever, the table makes a good comparison chart of the benefits of all grains.

If you keep horses, sheep, or rabbits, it will pay you to grow oats. Even a small patch in the garden will save money on your rabbit-feed bill. You don’t even have to thresh the grain out, just feed it, stalks and all, to these animals or other kinds of livestock. Recent experiments by Ohio State in the southern part of the state indicate that oats, sown in late summer, can provide high-quality winter grazing for cattle and sheep.

Oats are good livestock feed when ground or rolled and mixed with ground corn. That’s the standard dairy-cow ration on most U.S. farms. Whole oats are excellent food for poultry, too; the hulls help prevent cannibalism. Chickens will eat more oats if they are rolled and mixed with milled corn and wheat. Given a choice between wheat and oats in their whole-grain scratch feed, they will invariably eat up all the wheat first. The oat hull that covers the groat so tightly on each grain may be good for them, but I suspect—as in the case with humans—the taste is not.

Oats make fairly good hay as well, though it takes a little longer to dry after mowing. Cut them when the grain is in the early milk stage, just beginning to fill out and the plant is almost entirely green yet. Yields of 8 tons per acre are possible or 600 pounds of plant protein per acre—not as good as alfalfa hay, but remember that you have to wait a whole year to harvest alfalfa after you plant it. You wait only two months for hay from a planting of oats. Be aware also that oat straw traditionally has been fed to cattle, especially oat straw stored in a stack. Such straw often still has a streak of green in the stalk, and hungry cows will eat it readily, especially when they are being fed a lot (too much) of corn.

Types and Varieties of Oats

Common white oats, Avena sativa, are by far the most widely grown species. They are planted in spring for midsummer harvest. Red oats, Avena byzantina, are the southern and south-central type, sown in the fall where winters are mild, for harvest the following summer. Hull-less or naked oats, A. nuda, are a rarely grown third type. In addition, there are the kinds of oats that young men sow before settling down to responsible adulthood. It’s a matter of opinion whether these oats are good or bad for society.

The distinction between white and red oats is often hazy except for the difference in planting time. White oats are more yellow than white, and red oats are often grayish in color. Many of the common white-oat varieties have red-oat parentage somewhere in their background. Clinton, one of the more successful white-oat varieties over the years, is actually a cross between white and red. ‘Cherokee’ and ‘Andrew’ are red varieties marketed as white, and ‘Missouri O-205’ and ‘Kanota’ are quite similar varieties marketed as red. The obvious deduction the reader should make is that variety in oats (and maybe most grains) is not that important, at least for the garden farmer.

Sources: For nutritional content, USDA Nutrient Data Laboratory online database at www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/. For recommended daily allowances, National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board, “Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs): Recommended Intakes for Individuals, Vitamins” at www.iom.edu/Object.File/Master/21/372/0.pdf, “Dietary Reference Intakes: Macronutrients” at www.iom.edu/Object.File/Master/7/300/Webtablemacro.pdf, “Dietary Reference Intakes : Electrolytes and Water” at www. iom.edu/Object.File/Master/20/004/0.pdf, and “Dietary Reference Intakes: Elements”” at www.iom.edu/Object.File/Master/7/294/0.pdf.

Many varieties of both white and red oats are available, but it’s not necessary for you to know them by name. That’s true of all cereal grains. The life of any one variety is apt to be quite short, limited to the five to ten years it takes for a disease pathogen to adjust to that variety’s inbred resistance. That’s why plant breeders have to develop new varieties with new resistances to disease constantly, and why I am loath to name names. Some have better milling quality, as millers would say, but I don’t think that is important for small-grain raisers. I’ve read that Quaker Oats goes right to the marketplace for its supply, selecting high-quality grain of whatever variety.

Oats respond to ample rains more than other cereal crops to make a good yield. They like fertile soil too (what doesn’t?) but will perform satisfactorily without high additions of fertilizer. In fact, you can easily get too much nitrogen in the ground for oats, especially in a garden situation where you’ve made the soil very rich. If a previous oat crop possessed a dark green color and much of it fell over on the ground before harvest, I wouldn’t add any fertilizer. Even on a commercial basis, if oats seldom lodge and maintain a healthy green color, add no more than 30 pounds of nitrogen and 10 pounds of phosphorus and potassium per acre. If oats are short and light green in color, ripening to a flat tan rather than a solid yellow, the soil needs about 60 pounds of nitrogen, 15 pounds of phosphorus, and 20 to 30 pounds of potassium. So sayeth the experts.

Such low amounts of fertilizer can be supplied organically at reasonable cost even on large fields. Legumes will fix that much nitrogen in the soil naturally. So a green-manure crop with some animal manure added, along with 2 tons of rock phosphate applied per acre every three years and about 2 tons of lime every five to ten years, should result in yields of 60 to 70 bushels per acre and more on good ground.

Fertilizer balance is the key. After applications of either organic fertilizer or inorganic chemicals, soil tests may show a field contains 150 pounds of available nitrogen, but only 30 pounds of potassium. That could spell trouble for a cereal crop like oats. It would grow big and heavy and fall over so flat on its strawy back that it can’t be picked up even by the most sophisticated combine header. If you have 150 pounds of nitrogen available, you ought to have at least 60 pounds of potassium available to give the stalks enough strength to match the heavy growth the nitrogen will cause. The garden farmer should think the other way. If you have 30 pounds of potassium, 60 pounds of nitrogen is enough. After all, you are not trying to pay your way to Bermuda on your oat profits.

Insects and Diseases

Oats have fewer enemies than corn or wheat: no Hessian fly, no chinch bug. Sometimes greenbugs, a type of aphid, will attack oats, but in many years a small wasplike insect, Adbidius testaceipes, keeps them in check.

Of the diseases that attack oats, crown rust is probably the most important, especially in southern and central areas. There’s no cure, just preventive maintenance. Use resistant varieties and cut out any buckthorn bushes near fields or gardens. The disease uses buckthorn as a host plant during part of its life cycle. That’s what the books say anyway. But at least one kind of buckthorn, ‘Cascara’, is renowned in folk medicine as an effective laxative. Perhaps the backyard oats grower with chronic constipation might decide to risk it.

Septoria leaf blight is another fungal disease that recurs in cereal crops, including oats. Again, crop rotation and resistant varieties are your best defense.

Quality is as important in grains as it is in fruits and vegetables. The grower must strive to keep them clean of insects, mold, and any other foreign matter. But just as important, grains in commerce must meet certain weight standards to qualify as good, better, or best, and this is especially true of oats. A bushel of oats is supposed to weigh around 38 pounds, but only plump, healthy, well-grown oats will actually weigh that much. Test weights of 36 and 37 pounds per bushel are considered very good, but when test weight falls below 30 pounds, you are handling many shriveled grains that contain little food value and low germination potential. Weight of a grain can also tell you something about its moisture content. The drier the grain, the more it will weigh in any given volume, everything else being equal. That may surprise you, but the moisture that swells the grains so that fewer of them fit into a bushel weighs less than the grains themselves. Removing the moisture allows more grains per bushel.

Oats Culture

Whether you plant in fall or spring, raising oats proceeds in similar fashion. Since my experience has been only with spring oats, I’ll describe that process. Southern growers can adjust what I say to their own fall-planting conditions, or proceed in a manner similar to what I described for planting wheat in the fall. For spring oats, the earlier you can plant the better. I have planted oats in Minnesota when there were still snowdrifts melting in the woods. Oats like cool weather and can get along just as well with cloudy weather as with constant sun. That’s why they are adapted so well to a place like Scotland. In the North and East in the United States, oats are a good crop to grow wherever potatoes grow well. The two seem to like a similar environment.

“Farmers,” says an old adage, “mud in the oats and dust in the wheat” to get good crops of both, referring to spring oats and fall wheat. The saying is more accurately a description of what usually happens rather than good advice. When you plant oats in the spring, you are usually battling wet weather, and when you plant wheat in the fall, you are contending with dry weather, whether you like it or not. Be that as it may, whenever the soil dries enough in spring to be workable, plant your oats. The longer you wait, the poorer your subsequent crop is likely to be.

If you have gardened a long time, you have noticed, I’m sure, that almost every year there is a short period of dry weather in early spring when the ground does dry out enough to till. The temptation, which most of us give in to, is to plant some early vegetables. About half the time this planting amounts to very little because the ground is still too cold for good germination, and more cold weather is going to come anyway. So instead of planting vegetables at that time, plant a patch of oats and you’ll be ahead on both counts.

The ground you intend to plant oats on will probably have been plowed or disked or rotary-tilled the preceding fall. Fall-worked ground dries out faster in the spring than spring-plowed, so you can get on it earlier. The finer the seedbed the better, but for oats you can be a little less finicky and get away with it. Invariably you are going to get more rain shortly, which will ensure that the soil settles over and around the oat grains well enough for good germination.

In the garden, you can do it all with a rotary tiller. Work the ground up, but not too finely, broadcast the seed by hand, scattering it as evenly as you can over the plot, then run over it lightly again with your tiller. This light second tillage covers the seeds adequately—at least partially. You don’t have to cover every single grain. With good moisture, the grains on top sometimes sprout faster than the ones covered.

On a larger plot or field that has been disked and harrowed, plant either by broadcasting or with a drill, as described in chapter 3. The seeding rate for oats is 2½ bushels per acre. The drill puts the grain in the ground and covers it automatically. Set the drill to plant the seed not more than 2 inches deep, and 1 inch is better in early spring. If you broadcast the seed, cover it by going over the ground very lightly with a disk or a harrow, or better yet, a cultipacker. You will get some seed planted deeper than 2 inches, and some barely covered at all, but don’t worry. Enough will germinate normally. Broadcasting won’t make as good a stand as drilling. That’s why most broadcasters will plant at a 3-bushel-per-acre rate, a little higher than the norm.

Weeds will be a problem in larger oats fields unless you follow a good year-round, year-in-and-year-out program of weed prevention. Once the oats are planted, you can’t get into them to cultivate, though on a small patch you can walk through and hoe out some weeds. If you are not farming organically, you can spray with a broad-leaved herbicide, which if used correctly won’t harm grasses like oats. According to science, oats produces its own natural herbicide, but I have my doubts as to its effectiveness, because I have seen some mighty weedy oat fields.

Or you can plant, in the garden, in rows wide enough apart to get the cultivator through. In this case some weeds will grow in the row, but you can take out enough of them to keep the oats growing fine. If the field was weedy last year, you can be sure your oats will be weedy too. The weeds won’t necessarily “take the crop” and might not even hurt your yield much, but they make harvesting more difficult and increase the problem of getting weed seed and weed chaff out of the grain.

You can harvest your oats as grain, as hay, or even as silage. For harvesting with a grain combine, wait until the crop is dead ripe. Or cut it, rake it as you would hay, and allow it to ripen in the windrow. The windrows are harvested with a special pickup attachment on the combine. In the more northerly states, this latter method is still used because farmers believe the grain ripens too slowly and unevenly in the uncut stalk. By cutting and windrowing, they can often get the grain harvested with less risk, since, if left standing to ripen, the grain may be knocked flat on the ground by a hard storm. (Of course, if it rains too long on the windrowed oats, part of the crop can be lost too. Farming is always a gamble.)

I know a farmer who used to cut and bale his oats as he did hay, and then feed it by the bale to his animals. His livestock ate the oats and some of the straw. The rest of the straw became bedding. Since oats was the only small grain he grew, this practice saved him from buying a combine.

You can cut the oats when the grain is just beginning to harden, and the stalks have still a little green in them. Tie the stalks into bundles, as described with wheat in chapter 3, and place the bundles into shocks, where the oats can finish ripening and drying somewhat protected from rain. Then rank the bundles in a barn or even outside like a double stack of wood with the butts of the bundles to the outside and the heads inside to protect them from rain. Feed the oats by the bundle as needed.

You won’t find this manner of harvesting, storing, and feeding oats advised anywhere else that I know of anymore. It’s a method out of the past, which fortunately fits the homesteader of the future. I was pleased to learn that as late as 1963 (and without doubt still true somewhere) USDA officials observed small homestead plots of oats being harvested in the central states with grain cradles and (more often) with old-fashioned binders, the oats then fed by the bundle unthreshed to livestock. I’m not surprised, but I am glad I can now point to experience other than my own to substantiate what I know is a very economical and practical way to feed grain to animals. Not only do the animals “thresh” the grain as they eat it, but they clean up most of the straw too. Any old-timer will tell you that cows and horses like oat straw. They will sometimes eat it for roughage as well as they eat hay. It isn’t as good for them as hay, we say, but who’s to argue with a cow? At least they consume more total roughage that way, which is all to the good.

Mice will get into oats stored with the grain still in the straw. That’s why you should feed these oats out through the winter as quickly as possible. Cats in the barn are a big help.

Oats for the Table

The oats you want for your own use you can thresh and winnow in the same way you would thresh wheat by hand. Thirteen-and-a-half bushels of good oats makes a barrel (180 pounds) of rolled oats, so you would hardly want more than a couple of bushels’ worth, assuming you are using other grains too. If you are harvesting your oats with a combine, or more likely are having it harvested by a farmer who has a combine, you can, of course, just take the grain from the combine bin and winnow it cleaner if necessary.

Oats are more difficult to prepare for human food than wheat. The tight hull around the oat groat needs to be removed. There are grain elevators and mills that dehull oats, but finding them means doing research. Doing research gives me a chance to rant again about the problems of hunting for hard-to-find farming tools and services. Most readers already know what I am going to say. But let us entertain this scenario: you have been gardening for a long time and now realize that there is no good reason why you aren’t growing grains as well as fruits and vegetables. You read what I am writing, but you have no other contact within farming circles, so you write to me for information or go on the Internet. That’s okay, but what you really need to do is to get into the farming loop in your own local area. Everybody’s talking about buying local food these days, and one of the best results of that effort is that it will force the urbanite interested in good food to get to know local farmers. I live in northern Ohio, and I am ill-suited to give you specific advice if you write to me from California. Get to know the farmers in your area. Go to farm-supply stores and ask around. Attend or join the small farm organizations in your area. Read magazines published specifically for small-scale farmers and garden farmers, such as Farming Magazine: People, Land, and Community or Small Farmer’s Journal.

Just as an example, when I was frantically searching for information about hulling oats, an invitation came in the mail from the Northern Plains Sustainable Agriculture Society to a symposium and farm tour in North Dakota. Meaning no slur whatsoever, I am just not used to thinking of the Dakotas as being on the cutting (or hulling, in this case) edge of organic grain production. How wrong I was. The brochure contained a veritable gold mine of sources for organic grains and services. One of quite a few ads was for “Domestic Hulling.” The email address given was buckwheat@ iw.net, so I presume the reference was mainly for buckwheat hulling. But anyone who knows about hulling buckwheat surely knows about hulling oats. Another ad was from Organic Grain and Milling (www.ceresorganic.com) in St. Paul, Minnesota. These milling businesses serve mainly commercial growers, but nevertheless I bet that anyone who belongs to the Northern Plains Sustainable Agriculture Society knows where you can get oats hulled in their region.

The Internet bristles with requests for information on where small, kitchen-sized hullers can be obtained, which means that interest is high. I’m sure that when entrepreneurs realize this, they will rise to the occasion. One place online to check out is the Plant Sciences Department at the University of California, Davis. There are folks working there who are interested in making small threshers and hullers for a home or kitchen situation. By the time you read this, they may be able to guide you to fruitful sources.

Having said all this, if you want to go it alone, here are some hints on how to get that oat hull off yourself. Commercial processors have found that heating the grain for one-and-a-half hours at a temperature of 180°F makes the hulls brittle and easier to remove. The heating also dries the grain down to around 8 percent moisture from storage moisture of about 12 percent, which helps maintain quality during storage. You can certainly do small batches by roasting your own oats in your oven.

One older method of removing the hulls after roasting is to grind them lightly between two carborundum or emery-stone disks moving in opposite directions. The disks have to be set very precisely, so that the space between them is just small enough for the stones to tear and scrape loose the hulls of the oats without pulverizing the groats.

In commerce, centrifugal, impact-type hullers use a high-speed rotor to throw the oats against a rubber liner hard enough to knock the hull loose and blow it away. Another way is to pass the oats through extremely sharp, whirling steel blades. The hulls are then winnowed from the groats.

The groats are steamed and passed through steel rollers for flaking and dried for old-fashioned oatmeal. Nowadays, when no one has time to enjoy a leisurely breakfast, we have oat flakes that will cook in three minutes or less, so that we have time to get to the office early and brag for three minutes about how we got to work before anyone else. To cut the time of cooking oats, the processors “steel-cut” the oat groats. All that means is that the oats are partially ground. Each groat is cut approximately into three parts.

Your blender will cut up the groats to any size you want, but it cuts up the hulls too. All that fiber may be healthful, but not tasteful. You can run the blender briefly and sift out or winnow out some of the hulls to get something approximating good oat flour.

You can set the “concaves,” as farmers call them, close enough to the whirling threshing cylinder on a grain combine so that the grains are not only knocked out of the stalks, but the groats out of the hulls. If roasted oats were run back through a combine adjusted that way, I believe dehulling would be nearly complete, but I’ve never tried such a trick. A more practical method would be to run the roasted grain through any kitchen mill and winnow or sift out the loosened hulls.

Fortunately, there is another way out of the dilemma. Earlier I mentioned a rarely grown oats, Avens nuda, or naked oats. This species does not have the tight hull around the groat. Although it is available from many northern farm-seed companies, it has not become mainstream because it doesn’t yield as highly as other oats and because birds love it. Both of these disadvantages make naked oats a good possibility for small-scale growers not looking for top yields and with small enough patches to protect them from the birds. After first promising my wife that I would not stare lasciviously at the crop when it matured, I grew naked oats many years ago. I planted about two acres with visions of money dancing in my head. I had an old Allis-Chalmers All-Crop grain combine then, and I intended to plant the seed I got on maybe ten acres and sell that crop for seed to homesteaders and garden farmers, whom I was convinced would want to grow their own oats someday. The birds swarmed in when the groats were in the milky stage and ate most of it.

But I should not have been so discouraged. Oats should yield an average 60 bushels to the acre—sometimes the yield is 100 bushels per acre. So, on a garden farm, one-twelfth of an acre should easily mean 5 bushels of oat groats. That will be enough for quite a few breakfasts. One-twelfth of an acre would take a plot of ground about 60 by 60 feet, which would not be too difficult to protect with bird netting during the grain’s milky stage.

A couple of other interesting tidbits about oats may be of interest to you. A common practice among strawberry growers used to be to grow oats in the strawberry patch for mulch. Instead of having to buy straw and transport it to the garden, gardeners broadcast-sowed the oats over the entire strawberry patch in the early fall or late summer. The grain would grow tall but would not have enough time to produce seed before frost killed it. Dead, the oat plants fell over and maintained a protective mulch over the berry plants.

On a more modern note, the University of Minnesota several years ago was experimenting with new ways to grow edible mushrooms. They reported that the mushrooms grew quite well in a “soil” composed almost entirely of oat grains.

Oat hulls, as a by-product of the oatmeal industry, are used to produce furfural, an important industrial solvent. Also, oat hulls have been used to polish the pistons of upscale cars like the RollsRoyce. That’s a nice detail you can use to impress your friends as you feed them a homemade oat cake.

Oat Recipes

¾ cup peanut butter

½ cup honey

1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

¾ cup nonfat dry milk

1 cup oatmeal

¼ cup toasted sesame seeds*

2 tablespoons boiling water Chopped nuts or toasted sesame seeds for coating balls

• Preheat oven to 200°F.

• In a medium-sized bowl, combine peanut butter, honey, and vanilla extract; blend thoroughly.

• Mix nonfat dry milk and oatmeal together. Gradually add to the peanut butter-honey mixture, blending thoroughly, using your hands if necessary to mix as the dough begins to stiffen. Blend in the toasted sesame seeds.

• Add 2 tablespoons boiling water to mixture, blending well.

• Shape into 1-inch balls. Roll in finely chopped nuts or toasted sesame seeds. For variety, roll half the mixture in chopped nuts and the other half in toasted sesame seeds.

Yield: approximately 3 dozen balls

1 cup oat flour (oatmeal may be ground in electric blender)

¾ cup soy flour

¼ cup sesame seeds

¾ teaspoon salt

¼ cup oil

½ cup water

• Preheat oven to 350°F.

• Stir together flours, seeds, and salt. Add oil and blend well.

Add water and mix to pie-dough consistency.

• Roll dough on greased baking sheet, to  -inch thickness.

-inch thickness.

Cut into squares or triangles and bake in oven until the crackers are crisp and golden brown, about 15 minutes.

Yield: 3 to 4 dozen crackers

3 cups oatmeal

1½ cups coconut, unsweetened

½ cup wheat germ (or soy grits, if preferred)

1 cup sunflower seeds

¼ cup sesame seeds

½ cup honey

¼ cup oil

½ cup cold water

1 cup slivered, blanched almonds

½ cup raisins (optional)

• Preheat oven to 250°F.

• In a large mixing bowl, combine oatmeal, coconut, wheat germ or soy grits, sunflower seeds, and sesame seeds. Toss ingredients together thoroughly.

• Combine honey and oil. Add to dry ingredients, stirring until well mixed. Add the cold water, a little at a time, mixing until crumbly.

• Pour mixture into a large, heavy, shallow baking pan that has been lightly brushed with oil. Spread mixture evenly to edges of pan.

• Place pan on middle rack of the oven and bake for 2 hours, stirring every 15 minutes. Add 1 cup slivered almonds and continue to bake for ½ hour longer, or until mixture is thoroughly dry and light brown in color. Cereal should feel crisp to the touch.

• Turn oven off and allow cereal to cool in oven. If raisins are to be added to cereal, do so at this point.

• Remove cereal from oven, cool and put in a lightly covered container. Store in a cool, dry place.

• Serve plain or with fresh fruit.

Yield: 5 to 6 cups

Traditional Irish Oatmeal Bread

8 teaspoons dry yeast

1 cup lukewarm water

1 tablespoon honey

¼ cup nonfat dry milk

1 cup water

½ cup oil

1½ teaspoons salt

4 tablespoons honey

2 eggs, well beaten

2 cups oatmeal

6½ cups whole wheat flour

1 cup currants

1 egg, slightly beaten

½ teaspoon water

• Dissolve yeast in 1 cup lukewarm water. Add 1 tablespoon honey.

• Combine nonfat dry milk and 1 cup water with wire whisk, and heat almost to scalding point. Add oil, salt, and honey.

Cool to lukewarm.

• In a large mixing bowl, combine milk mixture, 2 wellbeaten eggs, and yeast mixture. Mix in oatmeal and 6 cups of the whole wheat flour, 3 cups at a time, reserving ½ cup for the second kneading.

• Knead until smooth and elastic, for 5 minutes.

• Put into an oiled bowl. Cover with damp cloth and let rise in a warm place until double in bulk, approximately 1½ hours.

• Stir dough down and knead with remaining ½ cup whole wheat flour, gradually working in currants. Shape into three round loaves. Brush the top of loaves with beaten egg to which ½ teaspoon water has been added. Put loaves on oiled cookie sheets to rise.

• Let rise 1 hour in a draft-free spot. Meanwhile preheat oven to 375°F.

• Bake in oven for 25 minutes until golden brown. Remove from pan and cool before slicing.

Yield: 3 round loaves

* Toast sesame seeds in oven for about 20 minutes or until lightly browned.