Assur: The History and Legacy of the Ancient Assyrian Empire’s Capital City

By Charles River Editors

American soldiers patrolling around Aššur’s ruins

About Charles River Editors

Charles River Editors is a boutique digital publishing company, specializing in bringing history back to life with educational and engaging books on a wide range of topics. Keep up to date with our new and free offerings with this 5 second sign up on our weekly mailing list, and visit Our Kindle Author Page to see other recently published Kindle titles.

We make these books for you and always want to know our readers’ opinions, so we encourage you to leave reviews and look forward to publishing new and exciting titles each week.

Introduction

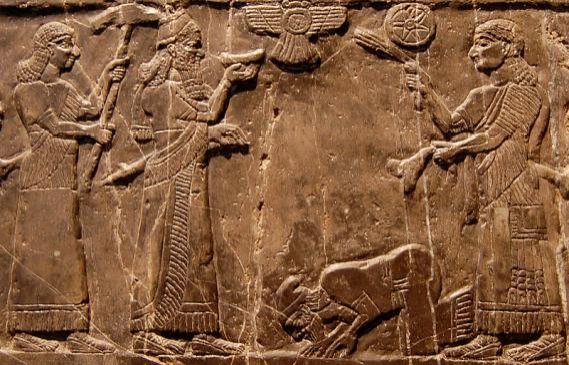

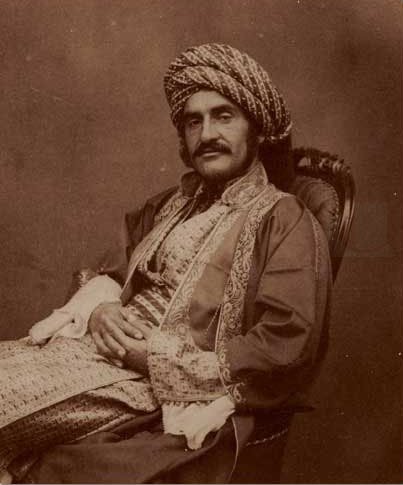

A relief depicting Ashurnasipal with official

Aššur

“All who hear the news of your destruction clap their hands for joy. Did no one escape your endless cruelty?” - Nahum 3:19

In northern Iraq, on the banks of the Tigris River, lie the ruins of the ancient city of Aššur. This was the first capital and the most important religious center of the Assyrian Empire. Underneath the cover of sand and soil are almost six meters of dense stratigraphic layers that reveal the passage of millennia. Known today as Qal’at Sherqat, and also as Kilah Shregat, the city dates back to the 3rd millennium BCE. In that time period, the Assyrian army became the largest yet seen, and their warriors were both the greatest and cruelest in the land. They conquered an empire from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea; they despoiled the great city of Babylon, and they enslaved the tribes of Israel. Even the pharaoh of Egypt paid them tribute. No army had ever carried war so far.

Indeed, Aššur was the heart of one of antiquity’s most infamous war machines. When scholars study the history of the ancient Near East, several wars that had extremely brutal consequences (at least by modern standards) often stand out. Forced removal of entire populations, sieges that decimated entire cities, and wanton destruction of property were all tactics used by the various peoples of the ancient Near East against each other, but the Assyrians were the first people to make war a science. When the Assyrians are mentioned, images of war and brutality are among the first that come to mind, despite the fact that their culture prospered for nearly 2,000 years.

Like a number of ancient individuals and empires in that region, the negative perception of ancient Assyrian culture was passed down through Biblical accounts, and regardless of the accuracy of the Bible’s depiction of certain events, the Assyrians clearly played the role of adversary for the Israelites. Indeed, Assyria (Biblical Shinar) and the Assyrian people played an important role in many books of the Old Testament and are first mentioned in the book of Genesis: “And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel and Erech, and Akkad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar. Out of that land went forth Ashur and built Nineveh and the city Rehoboth and Kallah.” (Gen. 10:10-11).

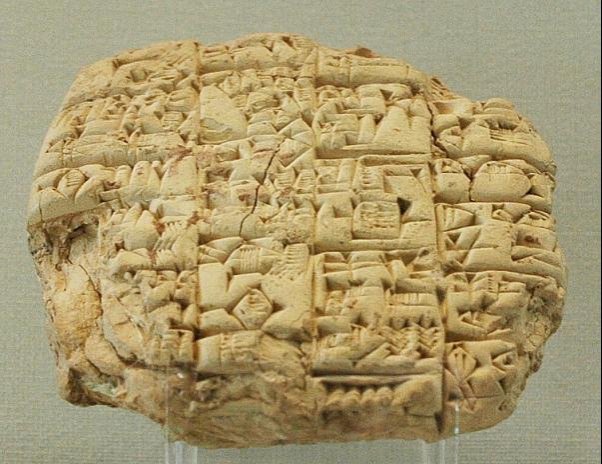

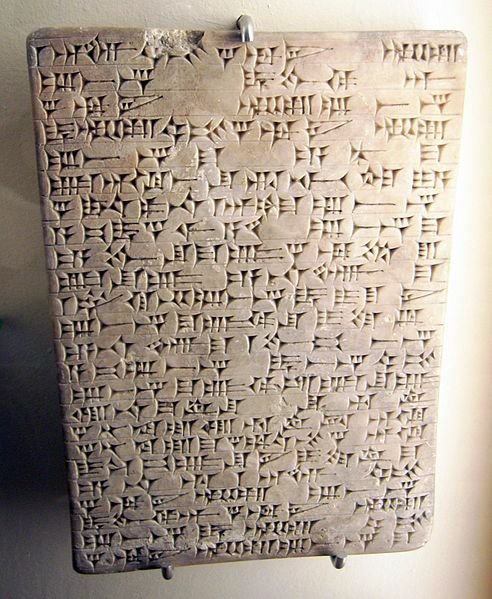

Although the Biblical accounts of the Assyrians are among the most interesting and are often corroborated with other historical sources, the Assyrians were much more than just the enemies of the Israelites and brutal thugs. A historical survey of ancient Assyrian culture reveals that although they were the supreme warriors of their time, they were also excellent merchants, diplomats, and highly literate people who recorded their history and religious rituals and ideology in great detail. The Assyrians, like their other neighbors in Mesopotamia, were literate and developed their own dialect of the Akkadian language that they used to write tens of thousands of documents in the cuneiform script (Kuhrt 2010, 1:84). Furthermore, the Assyrians prospered for so long that their culture is often broken down by historians into the “Old”, “Middle”, and “Neo” Assyrian periods, even though the Assyrians themselves viewed their history as a long succession of rulers from an archaic period until the collapse of the neo-Assyrian Empire in the 7th century BCE. In fact, the current divisions have been made by modern scholars based on linguistic changes, not on political dynasties (van de Mieroop 2007, 179).

Although war played such a central role in Assyrian society, they were also active and prosperous traders, and trade was an essential part of Aššur’s growth from its earliest stages. Strangely, even during military campaigns, merchants from the city engaged in commercial interactions with the “enemy,” for example with the Aramaeans during the campaigns of Adad Nirari II. As opposed to other cities in Mesopotamia, Aššur’s location meant that it was especially subjected to the influences of its many neighbors in southern Mesopotamia; Anatolia, Syria, the Zagros Mountains, and even from the barbarian tribes north of the Caucasus Mountains. Their presence can be seen today in the architecture and artifacts of the ruined city.

Aššur: The History and Legacy of the Ancient Assyrian Empire’s Capital City looks at how the Assyrian city was built, its importance, and its collapse. Along with pictures depicting important people, places, and events, you will learn about Aššur like never before.

Assur: The History and Legacy of the Ancient Assyrian Empire’s Capital City

Sumerian and Akkadian Origins of Aššur

The Pantheon of Northern Mesopotamia

The Decline and Rediscovery of Aššur

Free Books by Charles River Editors

Discounted Books by Charles River Editors

Geography

The name Assyria is actually a modern derivation of the name of the ancient city of Aššur (Ashur in English), which is where Assyrian culture began (Kuhrt 2010, 1:82). The ancient city of Ashur was located approximately 100 kilometers (62 miles) south of modern Mosul, located along the banks of the Tigris River in what is today the state of Iraq (Kuhrt 2010, 1:81). As such, Ashur was part of greater Mesopotamia and the Fertile Crescent region, which allowed the city to grow in terms of both culture and population. Assyria was provided with plenty of water from the Tigris River, and it was also on the fringes of the rainfall zone, which meant that it was not totally dependent on irrigation (Kuhrt 2010, 1:81).

Location allowed the population of Assyria to grow, but its culture flourished due to its proximity to southern Mesopotamia, particularly cities such as Babylon, Ur, and Larsa. The Assyrians encountered and adopted concepts already in use by their neighbors, including writing, which spurred the Assyrians’ advancement and has since made it much easier for people to study them.

Joey Hewitt’s map of Mesopotamia during the 2nd millennium BCE

A letter sent circa 2400 BCE by the high-priest Lu’enna to the king of Lagash informing him of his son's death in combat.

The Assyrians’ development of writing allows current historians to read about the empire’s affairs, but it also allowed the Assyrians themselves the ability to document their own history. The Assyrians’ idea of history was essentially the same as that of their Babylonian neighbors to the south and involved ideas such as destiny that were manifested in the past and projected forward into the future (Speiser 1983, 38-39). As such, the Assyrians’ view of history was fundamentally different than the modern view. Modern notions of history are largely derived from the ancient Greeks, who believed that history should be written as a narrative and serve to teach those who read it. Modern views of history are largely divorced from ideas such as divine intervention, but to the Assyrians, it was the divine that made history, and as a result, they believed mortal failures were the result of not following divine law. In other words, history to the Assyrians was a theocratic history (Speiser 1983, 55-56).

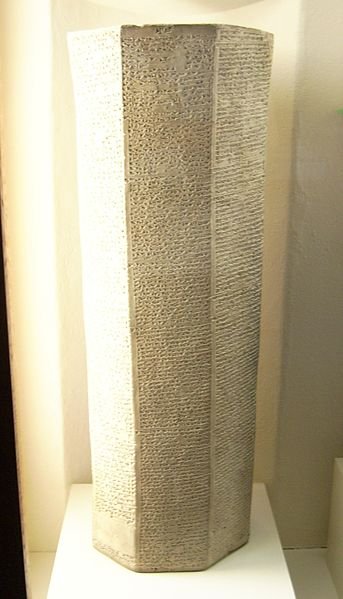

Despite Assyrian historiography’s long and apparently unchanging background from early Mesopotamian origins, the Middle Assyrian period witnessed a major change in Assyrian historiography. During the reign of Tiglath-pileser I (ca. 1114-1076), the Assyrians began to write royal annals which consisted of chronologically detailed accounts of military expeditions and royal hunts (van de Mieroop 2007, 180). The manner and context in which these annals were first composed is unknown, but it is possible these reports were initially meant to be letters from the kings to their gods (Speiser 1983, 66). The annals were incredibly specific in regards to geographic locales and ethnic groups affected by military campaigns, and they also graphically depicted the brutal nature of Assyrian warfare.

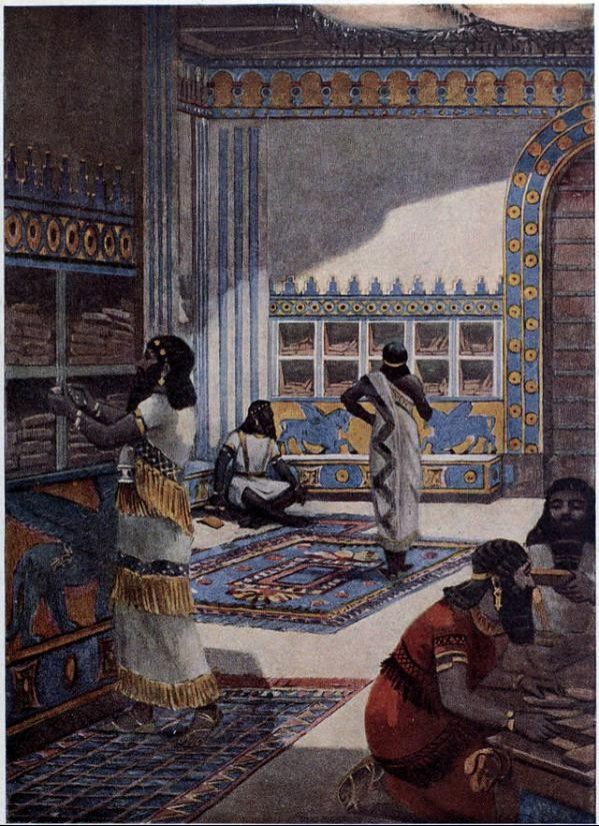

The location where many of these annals were located and subsequently discovered was in the library of king Ashurbanipal (668-631 BC). Over 5,000 cuneiform documents, which detailed affairs of the state and historical annals, were recovered from the ruins of Ashurbanipal’s library (van de Mieroop 2007, 261). The discovery proved yet again that the Assyrians, far from simply being bloodthirsty warriors, placed a premium on literature and history.

An illustration depicting the library of Ashurbanipal

The Assyrian historical annals may have been the most interesting and entertaining form of Assyrian documents, but the royal king-lists have helped modern scholars accurately recreate Assyrian chronology. The Assyrians, like the Babylonians to the south and the Egyptians to the west, kept records of all their kings in what are known today as king-lists. King-lists could be as simple as an ordered listing of all kings, or they could include such things as length of reign and other important facts. At this point, three Assyrian king-lists are known to exist: one list ends in 935 BC, while the other two end in 745 and 722 BC (Pritchard 1992, 564).

The depiction of a high priest on the left and a king on the right

As for the Assyrian capital, the climate and landscape were of key importance for Aššur’s foundation and growth. The site was located approximately 180 miles north of Iraq’s current capital, Baghdad, in the northern part of ancient Mesopotamia. Approximately 5,000 years ago urbanization started in the land meso- (“between”) the Tigris and Euphrates potamos (“rivers”). Northern Mesopotamia was unlike the South or the Indus Valley, with their regular flooding and easy irrigation. A lot of slave labor was needed to make the fast-flowing Tigris useful for irrigation, but the well-watered and fertile highland region of Assyria generally had a better climate and better access to resources than that of Babylonia and the south.[1]

The rivers were difficult to navigate, and their flooding was unpredictable in timing and force. This meant that the region of what would become Assyria was prone to rapidly switching between devastating floods and horrible drought – a seemingly random cycle that tended to be attributed to the capriciousness of the gods.

That said, Aššur was well-situated in the rain belt of what would become northern Iraq, an area with extremely hot and dry summers and cold winters. The kingdom was made prosperous by this strategic location overlooking the river route that connected northern and southern Mesopotamia, and the land routes connected to Anatolia and the Eastern Mediterranean.

The city itself was located on the right bank of the Tigris River, midway between the Greater and the Lesser Zab. 60 miles to the north, beyond the Greater Zab, was the location of the great contemporary city of Nineveh. The settlement of Aššur developed upon a rocky plateau in the Jebel Hamrin mountain range that rose high above and overlooked the west bank of the Tigris River. It was a location that provided the city with an excellent view of the surrounding landscape, while the steep slopes of the hill to the north and east provided natural defenses.[2] Although the city of Aššur itself was well-defended, the wider Assyrian heartland was poorly protected, and the fertile flood plains of the Tigris River Valley provided a tempting target for successive powers over the millennia.

From the end of the 3rd millennium BCE, the climate generally worsened in the region, which might indicate why the semi-nomadic peoples of northern Mesopotamia chose to settle at Aššur. In the vacuum left behind by the collapse of the Third Dynasty of Ur Empire, a great number of semi-nomadic Amorite groups moved into the region.[3]

Early Mesopotamian cities such as Aššur engaged in a form of proto-socialism, where farmers contributed their crops to public storehouses under the organizing influence of a central bureaucratic organization. From these storehouses, laborers would be paid uniform wages in grain.[4]

One of the most enduring legacies of ancient Mesopotamia was the conflict between country and city – in which texts such as the Epic of Gilgamesh frequently portray settlements as being the victors, resulting in what is known as city-states.[5] The city-state period in Mesopotamia was shaken in about 2,000 BCE – likely due to drought and a shift in the course of the rivers – and the environmentally weakened cities became increasingly threatened by pastoral nomads that then came from the east.[6]

Sumerian and Akkadian Origins of Aššur

What was to later become the great Assyrian empire arose in approximately 3100 BCE from humble origins as a small city-state centered on Aššur, from which they drew their name, contemporary to the Jemdet Nasr (3100 – 2900 BCE) and Early Dynastic (3000 – 2300 BCE) periods of southern Mesopotamia.[7] The kingdom of Sargon of Akkad (ca. 2334 – 2279 BCE) was located very close to Aššur, which was conquered and became an important Akkadian center of governance under the Akkadians. One of the earliest rulers of the city to be identified from the period of Akkadian rule was Ititi, who was described as an “overseer” – perhaps of the deity Ashur.[8] The same document that identifies him mentions the site of Gasur, also known as Nuzi (modern Yorgan Tepe) – an important settlement southeast of Aššur established during a time in which the Akkadians were increasingly focused on expanding their territory into northern Mesopotamia.[9] Even though Sargon the Great was the conqueror, the Assyrians eventually came to define the people of Akkad as being Assyrian and vice versa, and in many ways, Sargon was considered as the first Assyrian king.[10]

Sargon’s empire fell to insurrection and invasion by the hoards of the Guti, a nomadic people based in the Zagros Mountains. After the fall of the Akkadian Empire in the 22nd century BCE, Mesopotamia entered a period of chaos and decline which was eventually brought to an end by King Ur Nammu of the Third Dynasty of Ur (approximately 2112 to 2004 BCE). During this time Aššur was a vassal city-state of Ur, a massive city located in southern Mesopotamia close to the Persian Gulf. For a period of approximately 100 years there was peace and prosperity in the land; farms prospered, and the temples and houses of Aššur were rebuilt, and new ones erected.[11] During the reign of the renowned Third Dynasty of Ur king, Amar Sin (1981–1973 BCE), Aššur was governed by an individual named Zariqun, who suppressed a rebellion that had sprouted there.[12]

While people are familiar with Assyria and the Assyrians, the city’s name itself is interesting and a point of scholarly debate because it is also the name of the primary Assyrian god. It is probable that in archaic times, the locals attributed divine attributes to a rocky outcrop named Ashur, above the Tigris River, which is where the city then got its name (Snell 2011, 49).

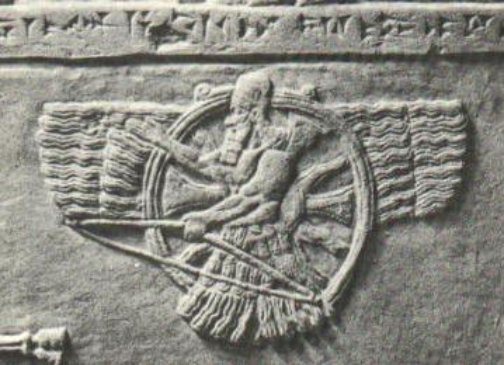

A Neo-Assyrian depiction of the god Aššur

Whether the god or the city actually came first may never be known for sure, but the city developed into a substantial state around the year 2000 BCE (Kuhrt 2010, 1:88). From their city, the Assyrians were able to develop far-flung and sophisticated trade networks in the late 3rd and early 2nd millennia BCE that would help establish it as a major urban center in the ancient Near East. A number of documents, written in Akkadian cuneiform, were excavated in Anatolia (modern Turkey) and have provided modern scholars with enough information to actually understand and recreate the trade routes and systems used by the Assyrians. For example, the documents show that Assyrian merchants developed trading towns in Anatolia where goods from Mesopotamia and Iran were traded for goods in Anatolia. There were two types of Assyrian trading towns: the karum, which meant quay or harbor in Akkadian, was the primary trading center of a city, while the wabartum was a smaller trading center that functioned in a subordinate manner to the nearest karum (Kuhrt 2010, 1:92).

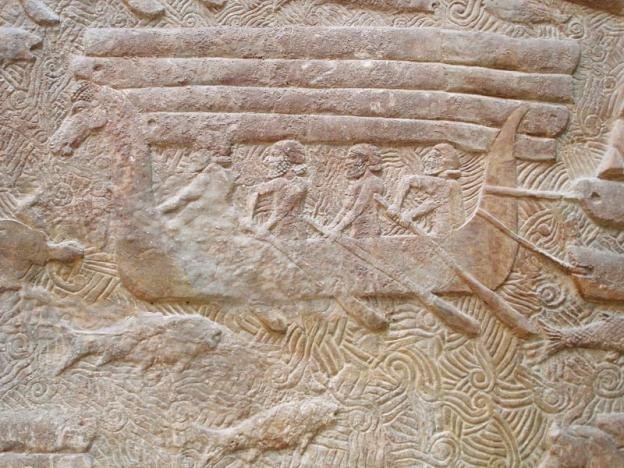

A relief depicting the transportation of cedar from Lebanon

Naturally, the city of Ashur acted as the central point in the trade routes. Tin from Iran and finished textiles from Babylon and southern Mesopotamia traveled through the city to the karum city of Kanesh in Anatolia (van de Mieroop 2007, 95). This journey from Ashur to Kanesh lasted about 50 days and was impossible during winter as the passages through the Taurus Mountains were blocked due to ice and snow (van de Mieroop 2007, 96). The Assyrian merchants carried the tin and textiles on donkeys that they all traded (including the donkeys) when they arrived in Anatolia for silver or gold that they then brought back to Ashur (Kuhrt 2010, 1:94).

One of the most interesting aspects of the Assyrian trade network was that it was carried out largely by private entrepreneurs. The Assyrian king was not directly involved (van de Mieroop 2007, 97), and it’s unclear why the Assyrian king did not take a more dominant role in the merchant activities of his people during the Old Assyrian period. Scholars have theorized that Assyrian kings might not have wanted to upset a system that worked, or that the kings were not yet powerful enough to influence such intricate networks.

The Pantheon of Northern Mesopotamia

Archaeologists at Aššur have discovered temples, documentary sources full of myths, and bas-reliefs showing rituals, providing a tentative understanding of the cosmological perspectives and religious rituals of the people in the city. The Assyrians spread their worldview like propaganda, through the use of monumental architecture, public festivals, and inscriptions describing the power of their king – all of which were designed to inspire awe in the empire’s subjects.[13]

Two of the most important deities in the northern-Mesopotamian pantheon from at least the time of the Sumerians were Enki and Enlil, the gods of creation and law. Enki was the lord of earth and waters, and was responsible for the creation of humankind. Humans were created out of clay and mud so that they could serve the gods as their slaves, but the gods also gave humans the ability to grow strong and wise. Enlil was the lord of air and the rules of reality, and was considered the ruler of the gods.

According to the Epic of Gilgamesh, both were important for life on Earth to exist, but they were portrayed as being constantly at odds with one another, and for this reason they are said to have represented the notorious duality of chaos/freedom and order/control. Eventually, the gods grew so tired of humanity’s rebellious nature that they created a flood with the intention of destroying the human race entirely. Enki warned a chosen few about the flood, and instructed them to build an ark that kept them, various seeds, and many animals from being obliterated.[14] Enki then pleaded with the gods to spare the humans, but it was too late; the floods raged on, and even though humanity seemed to be dead, Enki continued to stress to the other deities the importance of saving the humans. Many of the gods came around to his arguments and realized their mistake, so they were delighted when Enki revealed that he had saved some of the Earth’s lifeforms. The tales of Enki and Enlil have a strong connection with all Abrahamic religions, being linked to Yahweh and the Garden of Eden.[15]

An ancient depiction of Enki

Much of what the Assyrians and Neo-Assyrians did was in the name of Ashur, the great patron saint of Aššur, whose divine regent was the king.[16] As regent of the gods on earth, the king of Assyria was divinely sanctioned to wage war.[17] Ashur brought prosperity to the Assyrians as long as conquests continued – if their conquests ever stopped, then the world would end – and for this reason later Assyrian kings would engage in annual military campaigns against their neighbors. In the seventh century CE the Neo-Assyrian king, Esarhaddon, wrote: “Ashur, father of the gods, empowered me to depopulate and repopulate, to make broad the boundary of the land of Assyria.”[18]

Many other deities were worshiped in Aššur before and during the Assyrian period. The Assyrian manifestation of Ishtar was called Ishtar Ashuritu, worshiped there from at least the Early Dynastic period.[19] As the goddess of battles, Ishtar was particularly revered by the warlike Assyrians. Sacrifices and prayers were sent to her before their campaigns; one such example expressed: “Oh though, heroine among the gods, like a bundle rip him open in the midst of battle; raise up against him a tempest, an evil wind!”[20] Cuneiform inscriptions at the cult center of Kar Tukulti-Ninurta indicate that Nusku, the deity of light, was worshipped there daily by the king during the Middle Assyrian period.[21] Others included Ninurta, the warlike god of nature; Shamash was the sun god, and supreme judge; the moon god Sin; and Adad, god of the storms.[22] One of the latest deities to be worshipped at Aššur was Nabu. Their temple was constructed in the late seventh century BCE.[23]

Marie-Lan Nguyen’s picture of an ancient depiction of Ishtar

The Early City

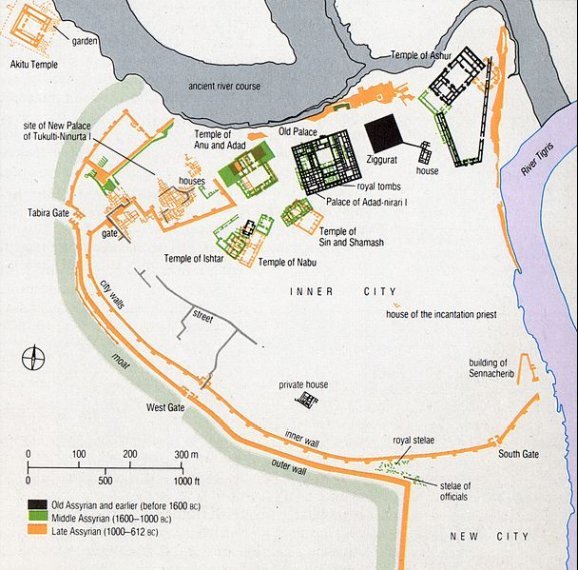

A layout of the site and its expansion

The earliest layout of the city, dating from the Sumerian and Akkadian periods, remains shrouded in mystery. Some have identified the site as Abarsal, a city described in early documentary accounts of trade between northern Syria and the upper Tigris, though in all likelihood this is wrong. Instead, it’s more likely the city was named through its association with Ashur from as early as the 3rd millennium BCE.[24] The earliest archaeological traces from Aššur that have been accurately dated are from 2500 BCE, with documentary sources from as early as approximately 2300 BCE.[25]

The city covered an area of approximately 70 hectares; an area that was peopled by kings, nobles, merchants, craftsmen, artists, scholars, farmers, and slaves. It can be divided into two broad areas. To the north is the Old City, libbi ali ("city center"), the largest part of the city and that which contained the most important structures. The New City, alu eshu, was constructed during the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE.[26] Access to the Old City was from the west, during the later periods of occupation via a series of heavily fortified gates.

The ancient Temple of Ashur was one of the earliest and most important structures in the city, built sometime between 2900 and 2600 BCE. It was located at the highest point of the rock upon which Aššur was situated. Known also as Esharra, or the “Temple of the Universe,” this complex was dedicated to Ashur, the patron deity of the settlement, whose stature in Assyrian society grew as the city flourished.[27] Some fine artifacts dating from the earliest periods of occupation have been discovered here, including a small stone vase decorated in high relief designs. The Temple of Ashur was modified and added to under the reigns of successive Assyrian kings.

To the west of the Temple of Ashur was the Ziggurat. This was a monumental temple built out of adobe bricks, which reached a height of 30 meters.[28] This structure was initially dedicated to Enlil, and then later to Ashur. The priests of these temples would have had much power, being able to communicate directly with the gods. In the temple at the top of the pyramid, kings and high priests made offerings and prayed for a good harvest. Any individual that was able to lead rituals to placate the impulsive gods were highly valued, and for this reason later Assyrian kings would begin to portray themselves as priestly figures.[29] It is also believed that ziggurats such as this could have been used as places of shelter when the River Tigris flooded. In the Old Testament, it is written that people and their livestock fled from the floodwaters into just such a building.[30]

The Temple of Ishtar was located at the center of the city. Its origins lie sometime between 2500 to 2334 BCE. This structure was built, demolished, and rebuilt many times over the millennia. Eight layers of temple foundations were recorded by archaeologists in the early 20th century, each being excavated, documented, and photographed or drawn before being destroyed to uncover the parts below. The earliest five layers were labeled the “archaic” temples, as no inscriptions were found that could reveal the names of the kings that ordered these structures to be built. These “archaic” levels date from between the Early Dynastic period to the Middle Assyrian period.[31]

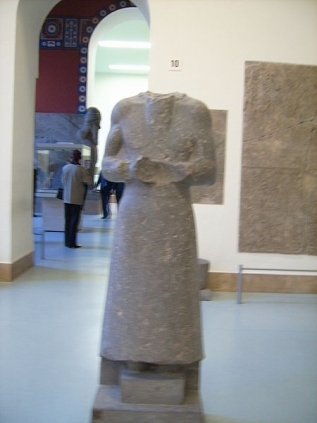

Sumerian and Akkadian styles of art and architecture from southern Mesopotamia are seen throughout the city. The Akkadian heartland was in southern Mesopotamia, but their dominance in the city is indicated by the presence of monumental royal statues discovered in the Ishtar Temple. One particularly well-preserved statue, made of diorite and dating from the late 3rd or early 2nd millennium BCE, shares the dorm and decorative style of works commonly found in southern Mesopotamia and Elam.

Marcus Cyron’s picture of a statue found at the site

Einsamer Schütze’s picture of a statue found at the site

The complex was approximately 120 square meters large. Access was from the west via a small foreroom, which led into a long corridor that opened into the main central courtyard. East of this was the so-called “Cult Room,” a long rectangular space with clay benches on three of the walls.[32] To the north was a room that served as a cellar, with a squat podium at one end. A great number of interesting artifacts have been recovered here, including offering stands, clay fragments of altars, and stands which may have been used to burn incense or place offerings, which together indicate the ceremonial function of this complex.[33] Ceramic vessels decorated with high-relief human figures and animals – likely lions and bulls – and carved stone figurines were also discovered there and dated to the Sumerian period of occupation.[34]

The most interesting finds from the Ishtar Temple were the house-shaped altars dating from the same time. These were in the form of a two-story building, the front faces covered in windows.[35] Impressions of contemporary cylinder seals show how these would have been used, with offerings and incense burners placed on top.

The buildings of Aššur remained in continuous use for extended periods of time and thus went through normal phases of disrepair and erosion in the harsh north-Mesopotamian climate. Therefore, they frequently required restoration and reconstruction; tasks that were undertaken under the orders of the reigning kings, who would record their prestigious acts (and those of their forebears) in order to portray their power and prestige. For example, many of the foundation documents left behind by Adad-nirari I are careful to pay homage to the public structures built and maintained by his predecessors before detailing the importance and extent of his own contribution.[36]

The Old Assyrian Period

After a century the Third Dynasty of Ur was shattered by the invasion of the nomadic Amorites, also known as the Semites. This initiated a period of turbulence, as several city-states vied for supremacy across the region. In the wake of the collapse of the Third Dynasty of Ur, Aššur managed to establish its independence. The early centuries of the 2nd millennium are known as the Old Assyrian period, a time in which the earliest documented kings of Assyria ruled.

One of the earliest and most important rulers named in the Assyrian king list – a genealogy composed of information from a number of documentary sources – was Shamshi-Adad I (approximately 1815 – 1782 BCE). The Assyrians recognized Shamshi-Adad as their first king, but interestingly, they also recognized his Babylonian origin: “Shamshi-Adad, the son of Ilu-kabkabi, went away to Babylonia in the time of Naram-Sin; in the eponymy of Ibni-Adad, Shamshi-Adad came back from Babylonia; he seized Ekallate; he stayed in Ekallate for three years; in the eponymy of Atamar-Ishtar, Shamshi-Adad came up from Ekallate and removed Erishu, son of Naram-Sin, from the throne.” (Pritchard 1992, 564).

Inscriptions from the reign of Shamshi-Adad demonstrate that although he was not from Ashur, he gave praise to the god Ashur and beautified the city. One inscription reads, “Shamshi-Adad, king of the universe, builder of the temple of Assur; who devotes his energies to the land between the Tigris and Euphrates. At the command of Assur who loves him, he whose (name) Anu and Enlil had named for great (deeds), above the kings who had gone before, the temple of Enlil, which Erishum, son of Ilu-shuma, had built, and whose structure had fallen to ruins: the temple of Enlil, my lord, a magnificent shrine, a spacious abode, the dwelling of Enlil, my lord, which had been planned according to the plan of wise architects, in my city Assur I roofed (that) temple with [cedars]; in the doors I placed door-leaves of cedar, covered with silver and gold. The walls of (that) temple, (laid) upon silver, gold, lapis lazuli, (and) sandu-stone, - (with) cedar-oil, choice oil, honey, and butter I sprinkled the mud-walls.” (Luckenbill 1989, 1:16). This passage also demonstrates another precedent that Shamshi-Adad would set for later Assyrian kings: the use of the epithet “ruler of the universe.”

Shamshi-Adad I was forced to defend the Assyrian frontiers from its neighbors to both the north and south. During this incessant conflict, the Assyrians developed armies of battle-hardened warriors.[37] With these soldiers, the city-state solidified into a stable and powerful organization, unlike the fragile and frequently overthrown settlements that existed elsewhere in Mesopotamia. In many ways, it was the military ethos forged during this time and preserved over centuries that made the Assyrians different. [38]They were fierce hunters, being attributed as having been responsible for the extinction of the Mesopotamian lion.[39] One later Assyrian king was said to have been responsible for killing 340 lions, 120 elephants, and countless other beasts.[40] However, it is important to note that the Old and succeeding Middle Assyrian armies were only peasant armies; there was no such thing as a professional standing army in the world at this time.[41] These warriors were forced to return to their homes each year to fulfill their agricultural commitments during the winter months, which limited the extent that the Assyrian kings could engage in military campaigns – a problem that would carry on long into the Neo-Assyrian Empire as well.[42]

With this military power, a territorial state began to take form, with Aššur as the central place of governance. The Assyrian city-state was similar to their predecessors but differed in a number of important ways. Early proto-socialism was replaced by an early form of private enterprise, by which people could produce or acquire as many resources as they liked as long as they paid a tax to the central government. Taxation became incredibly important in the creation of a stable social order, as vassal states would send tribute to the Assyrian king. In doing so, they created one of the earliest examples of the important and durable forms of political organization in world history: the empire. The characteristic elements of “empires” were not invented by the Persians or Romans but had been developed and refined long before these great powers by the Assyrians. They demonstrated a desire for a unified world, an economy based on taxes and tithes from vassal states that were indirectly ruled, which also entailed allowing local customs and systems of rule to continue as long as the Assyrian dominance was acknowledged.[43] The problem with such empires is that they were diverse and multiethnic, which has historically made them difficult to unify, let alone maintain, over long periods of time.

Around the time of the rise of the Assyrian Empire, the responsibility of the well-being and social order of the city-state’s population shifted from goods to people, as great palaces for royal elites emerged in cities across the region. These kings, most of whom were successful military leaders or rich landowners, took on a quasi-religious role, portraying themselves as regents or deputies representing the wishes of the gods.[44] They recorded their role in society through public inscriptions in the cuneiform script, which became adopted to record a wide range of quotidian transactions. Socially-stratified class distinctions emerged between the royalty, priests, and commoners – and written languages played an important role in widening the gap between these classes.

Marcus Cyron’s pictures of tablets found at the site

Aššur served as the political, religious, and cultural heart of the Old Assyrian Empire. Most of the structures erected during the Sumerian and Akkadian periods continued to be used, and many new building complexes were constructed. The rulers of the Old Assyrian Empire did not reside exclusively within Aššur; for example, Shamshi-Adad I had a palace in Shubat Enlil (“the Home of Enlil,” also known as Shechna). Despite its distance from Aššur, he involved himself in building projects in the city and even embarked on military campaigns to the Levant in order to acquire timber for the restoration of the Temple of Ashur.[45]

A relief depicting the transportation of cedar from Lebanon

The most notable addition to the city during this time was the Old Palace, a 10,500 square meter complex located adjacent to the Ziggurat.[46] This was the primary residence of the Assyrian royalty and served as the focal point of administration and trade in the city. 24 Assyrian kings of the Old, Middle, and Neo-Assyrian periods contributed to its development by restoring, enlarging, and rebuilding its parts during their reigns. Its origins lie in the Old Assyrian period, and it was finally abandoned in the wake of the destruction of the city by the Medes in 614 BCE.[47]

Little is known of the original ground plan, the construction of which is generally attributed to King Shamshi-Adad I. In fact, the only real evidence we have of its existence, archaeological or documentary, is a reference to its destruction by Puzur Sin (a vice-regent in the city between 1639 and 1628 BCE). “On the command of the god Ashur, my lord, I destroyed the buildings he worked on, the city wall, and the palace of Shamshi-Adad.”[48] More information is known about the Middle Assyrian period of the building’s layout and uses, though one could infer a similar ground plan having existed at an earlier phase. It was composed of a central courtyard which gave way to four palatial wings to the northeast, southwest, and east. The main entrance to the palace was from its northwestern wing. The throne room, called the bit labuni, was situated within the southwestern wing, and the ekal kakki (“Palace of Weapons”) was located in an annex affixed to the northwestern wing. The palace was furnished with wall slabs carved with bas-reliefs, and sculptures made of basalt and limestone.[49]

One particularly interesting feature discovered by archaeologists close to the later Sin and Shamash Temple (discussed further below) was a burial dating from the Old Assyrian period. This has been interpreted as being the grave of a wealthy merchant that lived in the city. Little remains of the skeleton and the grave itself is unremarkable, being nothing more than a simple rectangular hole cut into the earth.[50] The significance of this burial instead lies in the huge amounts and quality of the grave goods buried alongside the individual, including a variety of ceramic objects, copper lance points, vessels, and daggers, and gold jewelry such as diadems, beaded necklaces, earrings and foot rings. Other jewelry was made of silver, lapis lazuli, agate, and other semiprecious stones. This veritable hoard of treasures also contained an ostrich egg and small figurines of gazelles that are believed to have been used during burial rites.[51] Beyond the immediate associations of this wealth with the individual buried in the same context, this hoard indicates the role of Aššur in wider networks of contact and trade throughout the region. The inventory of objects contains materials that are not native to northern Mesopotamia, which indicates that mercantile links were being made between Aššur and southern Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Afghanistan during this period or even earlier – the objects may have already been quite old before being placed within the grave.[52]

After the death of Shamshi-Adad I, he was succeeded by his son, Ishme Dagan I (1782 – 1742 BCE), but under his rule, the Old Assyrian Empire fell into decay, with Aššur existing as just one of many city-states that were vying for power in the area. A veritable “dark age” followed between approximately 1700 and 1365 BCE, during which time Aššur became dominated by Babylon.[53] Shamshi-Adad I was a contemporary of King Hammurabi, one of the most famous of the ancient Mesopotamian monarchs. Hammurabi ruled the relatively new kingdom of Babylon from 1792 to 1750 BCE and captured Aššur in approximately 1759 BCE. One of his most influential legacies was the law code that he enforced throughout his territories, which established everything from the wages of ox drivers to the punishment of taking an eye being to have one’s own eye taken – a principle that was later repeated in the Law of Moses.[54] Through the law codes, Hammurabi tried to portray himself in two roles: a shepherd that brings peace, and a benevolent father, and such an image became shared by the Assyrian leaders.[55]

The Middle Assyrian Period

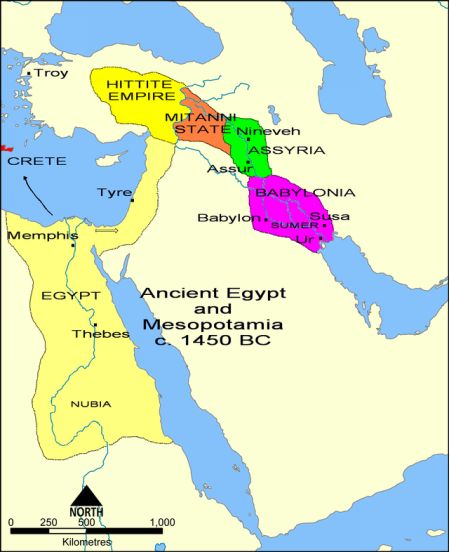

A map of the different empires in the region during the 15th century BCE

In the 15th century BCE, tribes of the Indo-European Mitanni came to the land, led by their king, Shaushtatar. The Mitanni captured Aššur from the Babylonians and turned the city into a vassal of their large empire.[56] However, the Mitanni state eventually became weakened and collapsed after the invasions of the Hittites from Anatolia in the 1300s BCE, enabling the Assyrians to throw off their yoke and become independent again.

The overthrow of the Mitanni kings by Eriba Adad I (1382 – 1356 BCE) and his son Ashur-Uballit I (1363 – 1328 BCE), marked the next phase in the history of Aššur: the Middle Assyrian Empire. Ashur-Uballit I established a dynasty of priest-kings that ruled over the city-state for the next four centuries.[57]

Spurred by their successes against the Hittites in the north, the Assyrians embarked on a series of military campaigns that expanded their empire across an area stretching from Carchemish on the Euphrates to Hanigalbat and Babylonia, to the Balikh and Habur river valleys.[58] Babylon itself was conquered by King Tukulti Ninurta I (1243 – 1207 BCE), at which point the Assyrian ruler began to identify himself as “King of the Universe.”[59]

Despite the environmental problems and threats caused their migration into northern Syria, under the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I the empire swelled once again. In a prayer, he praised Ashur as follows: “Ashur and the great gods who have enlarged my kingdom, who have given me strength and power as my portion, commanded me to extend the territory of their country, putting into my hand their powerful weapons, the cyclone of battle. I have subjugated lands and mountains, cities and their rulers, enemies of Ashur, and conquered their territories.”[60] The Assyrians experienced a Golden Age under the rule of the successors of Tukulti Ninurta I; there was no other power in the region that could rival them, other than the growth of the Aramaeans.

Tukulti-Ninurta constructed a cult center and his palace in Kar Tukulti-Ninurta, located a short distance northeast from Aššur, in which he was eventually assassinated by his son.[61] Considered as an extension to Aššur by present-day scholars, this site contains some of the best-preserved examples of Assyrian wall paintings that were discovered as fragments by archaeologists in the 1910s, but which have since been extensively studied and reconstructed.[62] The general form of these paintings was of a monochrome red background and long black stripes along the base, above which various images were painted: geometric motifs, naturalistic patterns, stylized sacred trees, animals, and figures.[63] The paintings from the south side of the palace differed, in that they had polychromatic backgrounds and images painted in exquisite detail. Scholars have analyzed the pigments used at Kar Tukulti-Ninurta, many of which were likely required to have been imported, which contributes to the general picture of Aššur’s role as a key node of trade and interaction in wider Eurasia.[64]

The Middle Assyrian king, Adad-nirari I (1305 – 1274 BCE), was evidently one of the most tireless and active builders in the history of Assyria. He oversaw the restoration of the Ishtar Temple, the rebuilding of the Temple of Ashur, the reconstruction of the Old Palace, the erection of city walls and gates, and the modification of the Ziggurat of Ashur.[65] Thanks to the numerous foundation documents that he left behind – no fewer than 58 stone slabs, 12 clay tablets, and 170 inscribed bricks – more is known about his life and construction projects than of any preceding ruler. It was during this time that temples devoted to numerous other deities were constructed in the city. A temple complex devoted to both Sin, god of the moon, and Shamash, god of the sun, was established in the northern part of the city, though little remains of this structure in the present day.[66] A second double temple was constructed during the 2nd millennium, this one being dedicated to the deities Anu, king of the gods and the sky, and Adad, god of the storms. This complex featured two tower-like ziggurats flanking a central courtyard.[67]

The Ishtar Temple was used as a place of burial during the Middle Assyrian period. A very well-preserved tomb was discovered in 1908 by German archaeologists at the southwestern corner of the temple complex, and was found to have been sealed and untouched since the time of its original use.[68] At the end of the year, the tomb was opened. What they experienced was akin to what Howard Carter found when he opened Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1923; the contents of the vaulted brick chamber were undisturbed, the skeletal remains intact, and no immediate evidence of a curse. Known today as Tomb 45, this tomb has served as an excellent time capsule from a particular point in time (the terminus ante quem being when the chamber was sealed sometime during the 14th century BCE),

The presence of multiple bodies – most of them female – indicates that it was used over a great length of time before this point. It contained a collection of clay tablets – the complete library of a man named Babu-aha-iddina.[69] Archaeological evidence suggests that the tomb would have been located beneath a house, perhaps the home of Babu-aha-iddina and his family who were likely the figures interred there.[70] Buried alongside the figures was a large inventory of grave goods: alabaster jars, ivory combs, lapis lazuli cylinder seals, rings, pendants, and necklaces made of gold and semi-precious stones, and a large quantity of ceramic vessels.[71]

One exceptional object found in this tomb was an inscribed cylindrical pyxis (a vessel with a lid that swiveled horizontally) made of elephant tusk.[72] The container was exquisitely decorated with naturalistic motifs and animals. Both the form and material indicate that connections existed between Aššur and the Levant and Egypt during this period, yet unlike the violent and chaotic scenes of nature used in these regions, the decorative scheme of the vessel from Aššur is distinctly peaceful and harmonious.[73] Also found in the tomb was a similarly decorated inscribed ivory comb. Together, these form the earliest examples of a fully developed Assyrian artistic style from the 14th century.[74] This was a time of intensive trade and communication between Assyria and its neighbors known as the "Amarna period," when fashions and artistic styles were changing across the region.[75]

Archaeologists have discovered more than 140 monumental stone stelae in various sizes in the New City, located to the south of the libbi ali. These were dedicated to the Assyrian royalty and city officials.[76] It is believed that these were originally located within or close to the Temple of Ashur, but were moved to this location during the Middle Assyrian period. They have served as a vital source of information regarding the city’s chronology and the genealogy of the Assyrian rulers.

As a result of the assassination of Tukulti Ninurta I, his successors faced frequent dissent and conflict over the legitimacy of their power, and the empire even devolved into civil war at times. Babylonia rose in rebellion, and the empire faced a number of conflicts in their northern and western territories, and also to the south against the Elamites in 1160 BCE.[77] Alongside these political events, there was a general social decline evident in the material record, with few new documents, works of art and architecture, and evidence of famine and crop failures in the Assyrian heartland.[78]

The late second millennium BC was a period of unrest in the Near East, especially as the Bronze Age was swept away and replaced by the Iron Age. The transition to the Iron Age proved to be especially violent, and it brought about the end of the Great Powers Club. A mysterious coalition of warrior tribes known collectively as the Sea Peoples ravaged the coastal kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean, and they destroyed the kingdoms of Ugarit and Hatti and nearly destroyed Egypt as well (Sandars 1987, 105-155).

Since they were located further inland from the Mediterranean coast, the Assyrians did not suffer as much from the Sea Peoples attacks, but the empire was not totally immune to the general situation either. A group of Semitic speaking people, known as the Arameans, began to attack and ravage numerous Mesopotamian cities around this same time (Haywood 2005, 41). The Aramean raids became the primary focus of Tiglath-pileser’s reign, a fact mentioned in the historical annals: “With the help of Assur, my lord, I led forth my chariots and warriors and went into the desert. Into the midst of the Ahlami, Arameans, enemies of Assur, my lord, I marched. The country from Suhi to the city of Carchemish, in the land of Hatti, I raided in one day. I slew their troops; their spoil, their goods and their possessions in countless numbers I carried away. The rest of their forces, which had fled from before the terrible weapons of Assur, my lord, and had crossed over the Euphrates – in pursuit of them I crossed the Euphrates in vessels made of skins. Six of their cities, which lay at the foot of the mountain of Beshri, I captured, I burned with fire, I laid (them) waste, I destroyed (them). Their spoil, their goods and their possessions I carried away to my city Assur.” (Luckenbill 1989, 1:83). However, despite Tiglath-pileser’s best efforts, the Aramean hordes eventually reduced the Assyrian Empire to its original heartland around Ashur by 1050 BCE (van de Mieroop 2007, 182).

The Arameans and the general collapse of the period may have reduced the land the Assyrians held, but Robert Drews has argued that their use of infantry helped them survive the collapse, whereas others, such as the Hittites, did not (Drews 1993, 140). The Historians' History of the World described Assyrian infantry: "The spear of the Assyrian footman was short, scarcely exceeding the height of a man; that of the horseman appears to have been considerably longer… The shaft was probably of some strong wood, and did not consist of a reed, like that of the modern Arab lance."

An illustration depicting an Assyrian soldier

It will probably never be definitively determined how and why the Assyrians survived the collapse of the Bronze Age, but Drew’s argument brings to light an important aspect of Assyrian culture that would define them in their golden age: their military prowess.

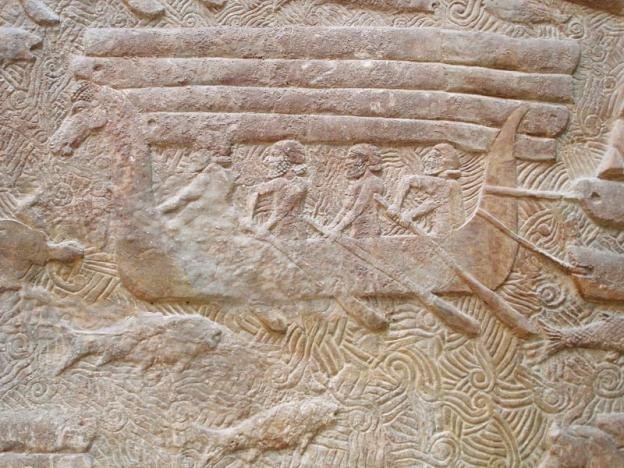

8th century depiction of an Assyrian warship

The Neo-Assyrian Period

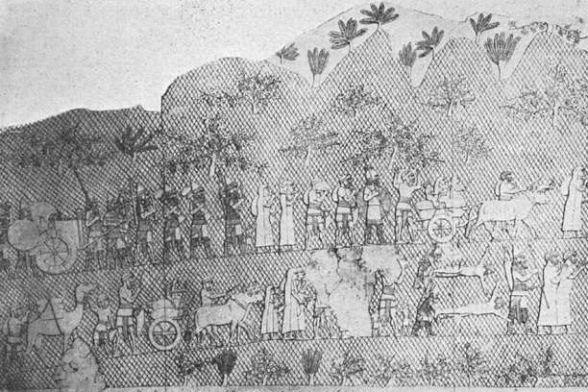

A relief depicting Assyrian archers and a siege weapon attacking a fortified enemy

The rich and fertile plains of northern Iraq, so inviting to be tilled, also beckoned to be plundered. A typical Assyrian needed in one hand his plowshare, and in the other a sword. By 1000 BCE Assyria – long a vassal to the Aramaeans and various other city states – had tired of foreign oppression. From approximately 900 BCE, Aššur regained its prominence as a political, religious, and cultural center with the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

The Chaldeans were a particularly strong influence by the 920s BCE, arriving at the same time as the Aramaeans after the “Late Bronze Age Collapse.” The Chaldeans initially occupied Babylonia and the marshlands southern Mesopotamia, close to the Persian Gulf, but from this area expanded northwards into northern Iraq.[79] By this time, the early Neo-Assyrian King Ashur Dan II had been engaging in annual campaigns against the tribes of Nairi around Lake Van, Cimmerians, Scythians, Aramaeans and Neo-Hittites to the north, northeast, and northwest – all in honor of Ashur.[80]

In 912 BCE, Ashur Dan II died, and his son, Adad Nirari II, came to power the following year after a brief civil war. Until his reign ended in 891 BCE, Adad Nirari II went to war every year – indeed, there is no record indicating that he did not go to war at any point. In 910 BCE he campaigned against the Aramaeans, winning a decisive battle at the junction of the Khabur and Euphrates.[81] This marked the first time since the Middle Assyrian era in which Assyria actively expanded their territory (the campaigns Ashur Dan II had engaged in sought to defeat foes, not gain new land).

Between 907 and 902 BCE, Adad Nirari II campaigned deep into the Aramaean heartland, eventually conquering the Sukhu Aramaeans, who henceforth paid tribute to Aššur, and later Babylon.[82] Beginning around 911 BCE the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew from its homeland around Aššur to include the whole of Mesopotamia, the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, and by 680 BCE even Egypt.[83]

Such expansion was thanks to the most brutal, terrifying, and efficient army that the world had ever seen. Assyria began to enlarge its borders, but with each change of seasons the empire withered. When autumn came, the soldiers returned to their fields. It was during these times that rebellions started, and the empire would shrink once again.[84] In 746 BCE there was a great revolt in Calah, located in between Nineveh and Aššur, which had been the capital of the Assyrian Empire since the reign of Ashurnasirpal II in 879 BCE.

Moreover, a plague was ravaging the Assyrian homeland during this time, and during the revolt, Ashur Nirari V died without an heir – the last of an extremely long lasting Neo-Assyrian dynasty, the Agaside, which began with King Bel Bami in 1700 BCE.[85] The governor of Calah, Pulu, managed to win the civil war and defeat the rebels and then, claiming to be the son of Adad Nirari III (a pedigree that most scholars believe was false), he took power of Assyria and assumed the name of Tiglath Pileser III.[86] His campaigns between 745 and 740 BCE and reforms transformed the empire completely, bringing back many old policies: deportations frequently occurred of up to 200,000 people to Assyria’s contested borders; eunuchs were installed as governors to prevent rival dynasties; vassal states were turned into provinces ruled by Assyrians; and the power of the semi-independent Assyrian nobility was restrained with a dual-position based administration.[87]

Tiglath-Pileser III vowed to make Assyria forever strong with its first standing army. Encouraged by the prospects of a career at arms thousands of young men enlisted. He created all of the institutions these soldiers would need, and left behind extensive documentary evidence of what this entailed, which provide a unique perspective into the Neo-Assyrian military structure.

Tiglath Pileser III had introduced for the first time a standing army that never demobilized during the winter, allowing the range of his campaigns to increase substantially. His campaigns across Babylonia, the kingdoms of the Zagros Mountains to the east, and Syria to the west were particularly bloody and successful, resulting in an empire whose borders stretched to a greater extent than had ever existed. His army was a meritocracy; generals weren’t chosen based on their family connections but based on their skill at military command.[88] Hundreds of thousands of people were deported from their homelands by the Neo-Assyrian conquerors, separating them from their histories and their families. In a similar fashion, skilled workers were sent across the empire to where they were most needed. Iron and bronze were the backbone of the Assyrian army.[89] Each soldier was issued a conical iron helmet, a sturdy breastplate of interlocking strips of bronze, and strong leather boots. The tallest men served as spear-carriers, wielding an iron-tipped lance, but were also armed with a dagger for close-quarters combat.[90] Some soldiers became archers, and some carried no weapons at all – their role was to protect other warriors, giving cover to the archers with shields four feet high that were made of leather and faced with beaten bronze or plated with wickerwork.[91]

Well-equipped as these foot soldiers were, the Assyrians sought even greater advantages against their foes. Horses were acquired for their chariots, and iron for their weapons. So important were they that the Assyrians avoided shooting horses during battle.[92] Timber was required for boats and siege engines. To get these commodities, the Assyrians campaigned farther and farther afield and brought the spoils of victory back to their homeland.

Of course, living off of the land meant that the great Assyrian armies were limited in how far they could travel. It was for this reason that the king set up huge granaries throughout the empire, ensuring that his troops could campaign up to 300 miles from a base of supplies.[93]

Like the Egyptians, the Assyrians had improved upon the clumsy four-wheeled chariots of Babylonia. Amassing their two-wheeled chariots like shock troops, they could break through an enemy’s line and shower them with arrows and spears. These were followed by another innovative class of soldier: the mounted archers. These consisted of two men riding two horses; one steering the animals and holding a shield, while the other used his bow.[94] Whoever fled was run down, and whoever remained was slaughtered.

The king rode at the front of his army, among his cavalry and chariots, followed by his infantry. Behind them, all snaked a long supply train, where craftsmen made weapons and armor as they rode. At the festival of the New Year, the king inspected his army, to ensure that it was always ready to fight.[95] Fed, clothed, and armed at his expense, the Assyrian warriors became the most professional army that the world had ever seen. At the outset, the Assyrians enjoyed an advantage possessed by few enemies: mobility. They would travel along good roads, maintained by the shovels of prisoners of war. On flat land, they could advance 20 miles each day.[96] By surmounting natural obstacles, especially rivers, the Assyrians reached new heights of ingenuity. Their chariots and siege engines were carried in large boats, with their horses swimming behind, while the troops traveled on inflated animal skins.[97]

Back in Aššur, the alu eshu (New City) expanded greatly to the south during the Neo-Assyrian period. Many substantially sized buildings were constructed there, including stables and arsenals for the Neo-Assyrian standing army and storehouses for their trading caravans and tax income. A large new structure surrounded by an expansive garden was built outside of the city walls by King Sennacherib. This was the Akitu Temple, where the annual New Year’s Festival was celebrated. The doors of the temple were allegedly decorated with battle scenes of the defeat of Qingu, the Babylonian god that was slain by Marduk.[98] Sennacherib also constructed a New Year’s Festival House and Processional Avenue on the relatively flat plain to the northwest of the city. A temple to the divine couple, Nabu, god of wisdom and son of Ashur, and his consort Tashmetum, “the lady who listens,” was constructed in the eighth century at the site of the Ishtar Temple.[99] The Neo-Assyrian kings actively restored the main sanctuaries and structures of the city, though in the 680s Sennacherib modified some of the religious sites, such as the Temple of Ashur, to accord with his reinterpretations of state theology.

Towards the end of the 2nd millennium BCE, the residential and administrative functions of the Old Palace appear to have transferred to the so-called New Palace, located in the western part of the libbi ali. This started under the reign of Tukulti Ninurta I, but was completed by Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883 – 859 BCE), the grandson of Adad Nirari II and one of the greatest kings of Neo-Assyria. Ashurnasirpal II reused building materials and decorative sculptures from the Old Palace to construct this new structure, which resulted in less than one-quarter of the Old Palace structure surviving into the Neo-Assyrian period.[100] The New Palace was decorated with carved wall slabs and lamassu bull statues - images of kingship and royal strength that were popular in the Babylonian cities.

Under the rule of Shalmaneser III (858 – 824 BCE), the libbi ali was enclosed by a massive double wall, complete with a deep moat. Access to and from the city center was controlled through three gates: the South gate, West gate, and Tabira gate. Most of the materials that he used to construct these fortifications came from the pre-existing Old- and Middle-Assyrian buildings, especially the ruinous Old Palace.[101]

While Northern Mesopotamia was fertile; it lacked almost all other important resources. Metal for tools, stone for sculpture, wood for construction and burning, all had to be traded for from neighboring lands, and indeed, long-distance trade from Aššur appears to have started during the Third Dynasty of Ur period. Merchants from the city established permanent mercantile colonies in Anatolia, known as karums, where they were involved in the east-west trade of textiles, tin, and silver. The best-preserved of these was at Karum Kanesh (Kültepe).[102] Although the Zagros mountain range separated Aššur from the lands farther east, these mighty mountains did not act as absolute boundaries, rather zones of integration and fragmentation.[103] Trading caravans embarked from Aššur across the mountains to destinations as far as Afghanistan, the Arabian Peninsula, and even the Indus River Valley.

The Assyrians sought a number of important commodities from these lands, foremost of which were iron, stone, wood, precious metals and semi-precious stones. An inscription dating from the 20th century BCE discovered at the Temple of Ishtar identifies the city as being involved in the trade of copper between northern and southern Mesopotamia, and even further afield to the region of present-day Oman. Elephants existed in Mesopotamia until approximately the 8th century BCE, though ivory was also imported from North Africa and the Indus River Valley.[104] In return, the Assyrian merchants brought much wealth, most of it plundered from their military campaigns or crafted in the workshops of Aššur and Nineveh.

One of the most important exports from Aššur would have been glass products, faience, and glazes of various types and colors. The region has a long history of glass production dating from at least the Sumerian-Akkadian period.[105] The city was ideally situated to make use of the abundant supply of silica, sodium oxide, and lime available in the landscape.[106] A vast inventory of glass beakers, urns, flasks, lidded jars, and mosaic tiles has been recovered from the tombs and burials of Aššur, most of them clearly displaying the tool marks left behind by the hands of Assyrian craftsmen thousands of years ago.[107]

The strategic location of the city meant that the Assyrian rulers could monitor the traffic and trade that moved along the Tigris River Valley. By the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE, grave goods recovered from burial tombs at the Old Palace site indicate the complexity and scale of the trading network Aššur was part of. By the 14th century BCE, the connections forged by this trade had resulted in a remarkable fusion of cultures in the city, with artistic and architectural elements from Egypt, Anatolia, Southern Mesopotamia, Syria, and the northern Mediterranean all found in the city.

The Neo-Assyrians have a deserved reputation for being the brutal bullies of ancient Mesopotamia, and their wrath was fully on display under the rule of one of Assyria’s most important leaders during the period: Sargon II (721-705 BCE), who restructured the Assyrian state internally, conducted military campaigns almost every year, and incorporated the conquered territories into provinces (van de Mieroop 2007, 248). In fact, one of the most notable changes he made to the Assyrian system was to increase the number of provinces from 12 to 25, which decreased the power of the provincial governors (van de Mieroop 2007, 248).

A relief depicting Sargon II meeting with a foreign dignitary

One of the most important provinces within the Assyrian Empire was Samaria. Also known as Israel, Samaria repeatedly rebelled against their Assyrian overlords, but in 722, the Assyrians overran Samaria once and for all, killing countless numbers and sending most of the rest of its inhabitants into forced exile. The events of Samaria’s fall were chronicled in the Assyrian annals from the reign of Sargon II and the Old Testament, and although the two sources present the event from different perspectives, they corroborate each other for the most part and together present a reliable account of the situation. The Assyrian record reads, “I besieged and conquered Samaria (Sa-me-ri-na), led away as booty 27,290 inhabitants of it. I formed from among them a contingent of 50 chariots and made remaining (inhabitants) assume their (social) positions. I installed over them an officer of mine and imposed upon them the tribute of the former king. Hanno, king of Gaza and also Sib’e, the turtan of Egypt (Mu-ṣu-ri), set out from Rapihu against me to deliver a decisive battle. I defeated them; Sib’e ran away, afraid when he (only) heard the noise of my (approaching) army, and has not been seen again. Hanno, I captured personally. I received tribute from Pir’u of Musuru, from Samsi, queen of Arabia (and) It’amar the Sabaen, gold in dust-form, horses (and) camels.” (Oppenheim 1992, 284-5).

The Assyrian account reveals that others in the region, namely the Egyptians, were involved on Israel’s side to a certain extent, but it is uncertain how many troops were sent with Sib’e because this account cannot be corroborated by any Egyptian source. Perhaps the most striking piece of information is that nearly 30,000 Israelites were removed from the region; the forced removal of rebellious populations by the Assyrians was a brutal but effective tactic that they commonly used.

The Biblical account of the fall of Samaria is quite similar to the Assyrian, but with a few minor differences. The account states, “And it came to pass in the fourth year of king Hezekiah, which was the seventh year of Hoshea a son of Elah king of Israel, that Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria and besieged it. And at the end of three years they took it; even in the sixth year of Hezekiah, that is the ninth year of Hoshea king of Israel, Samaria was taken. And the king of Assyria did carry away Israel unto Assyria and put them in Halah and in Habor by the river of Gozan, and in the city of the Medes.” (2 Kings 18:9-11).

This relief depicts the king of Israel, Jehu, bowing before the Assyrian king, Shalmaneser III, during the 9th century.

This relief depicts a forced removal of Judeans during the 8th century

The Assyrian siege and destruction of Samaria seemed to set into motion a chain of events of similarly brutal sieges that the Assyrian war machine meted out to rebellious provinces and any others who stood in its way in the late 8th and early 7th centuries BCE. A few years after he destroyed Israel, Sargon II turned his attention to one of Samaria’s neighbors, the coastal city of Ashdod. According to the annals from the Assyrian city of Khorsabad, Iamani, the king of Ashdod, decided to abandon his subordinate status to Assyria in favor of Egypt, which was ruled by the Nubians at the time. The text states, “Iamani from Ashdod, afraid of my armed force (lit.: weapons), left his wife and children and fled to the frontier of M[usru] which belongs to Meluhha (i.e. Ethiopia) and hid (lit.: stayed) there like a thief. I installed an officer of mine as governor over his entire large country and its prosperous inhabitants, (thus) aggrandizing (again) the territory belonging to Ashur, the king of the gods. The terror (-inspiring) glamour of Ashur, my lord, overpowered (however) the king of Meluhha and he threw him (i.e. Iamani) in fetters on hands and feet, and sent him to me, to Assyria. I conquered and sacked the towns Shinuhtu (and) Samaria, and all Israel (lit: ‘Omri-Land’ Bit Ḫu-um-ri-ia). I caught, like a fish, the Greek (Ionians) who live (on islands) amidst the Western Sea.” (Luckenbill, 1989, 40-41).

At first, this text appears somewhat confusing, but a closer examination reveals not only the Assyrians’ military might but also the complex geopolitical situation in the Near East at the time. Iamani fled to Egypt (Musru), which was in fact ruled by Shabaqa (716-702 BC) and the Nubian Twenty Fifth Dynasty (Meluhha), where he was then turned back over to the Assyrians. It appears that the Nubians under Shabaqa were “in no mood to incur the wrath of the Assyrian king” (Spalinger 1973, 97).

Although the rebellious Iamani’s sojourn in Egypt was short lived and Sargon II never turned his fury towards the Nile Valley, subsequent kings in both Assyria and Egypt set the stage for a conflict that devastated Egypt and left her temporarily under Assyrian rule. Spalinger contends that the Assyrians never intended to invade Egypt, but due to the Nubian dynasty’s meddling in Assyria’s affairs in the Levant, they were eventually compelled to act (Spalinger 1974b, 325). The first major conflict between Egypt and Assyria took place in the Levant near the city of Eltekeh in 702/701 BC. The Egyptians were led by the Nubian crown prince Taharqa (690-664 BC) – although the king during the battle was Shebitqu (702-690 BC) – and were allied with the kingdom of Judah against the Assyrian king Sennacherib (704-681 BC). 2 Kings 19:9 and Isaiah 37:1 both mention that “Tirhakah king of Ethiopia” led a force to help support the Judah king, Hezekiah, against the Assyrian siege, while an Egyptian source eludes to the crown prince’s journey to the Levant. It states, “He (Taharqa) came Upstream to Thebes, in the midst of fine youths, his majesty, king Shebitqu, justified, went after them to Nubia, he was with him. He loved him more than all his brothers. He passed by the home of Amen Gempaaten and he worshiped before the door of the temple with the army of his majesty, sailing north together with him.” (Macadam 1949, 1:14-21). Crown prince Taharqa then joined Hezekiah and his army against the Assyrians.

The confusion in the Biblical accounts concerning the correct name of the Egyptian-Nubian king can be ascribed to the fact that “the existing narrations were drawn up at a date after 690 B.C., when it was one of the current facts of life that Taharqa was king of Egypt and Nubia” (Kitchen 2003, 159-60).

The Assyrian historical annals give a more detailed account of the battle and its aftermath: “The officials, nobles and people of Ekron, who had thrown Padî, their king, bound by (treaty to) Assyria, into fetters of iron and had given him over to Hezekiah, the Jew (Iaudai), – he kept him in confinement like an enemy, – they (lit., their heart) became afraid and called upon the Egyptian kings, the bowmen, chariots and horses of the king of Meluhha (Ethiopia), a countless host, and these came to their aid. In the neighborhood of the city of Altakû (Eltekeh), their ranks being drawn up before me, they offered battle. (Trusting) in the aid of Assur, my lord, I fought with them and brought about their defeat. The Egyptian charioteers and princes, together with the charioteers of the Ethiopian king, my hands took alive in the midst of the battle. . . I besieged Eltekeh (and) Timnah, conquered (them) and carried their spoils away. I assaulted Ekron and killed the officials and patricians who had committed the crime and hung their bodies on poles around the city . . . As to Hezekiah, the Jew, he did not submit to my yoke, I laid siege to 46 of his strong cities, walled forts and to the countless small villages in their vicinity . . . I drove out (of them) 200,150 people . . . Himself I made a prisoner in Jerusalem, his royal residence, like a bird in a cage.” (Oppenheim 1992, 287-88)

Hezekiah and Judah made a disastrous miscalculation when they decided to rebel against Assyria, but the Egyptian-Nubians made an even more fatal mistake because their interference in Assyrian affairs would eventually lead to the collapse of their dynasty. While Sennacherib’s war against the Egyptians was the first of its kind, it was short-lived, and he never attempted an actual invasion of Egypt. However, Sennacherib’s successor, Esarhaddon (680-669 BC), took the next logical step and attempted two invasions of Egypt. Esarhaddon’s attack in 674 BC was unsuccessful, but he was finally able to conquer Egyptian territory on the edge of the eastern Delta in 671 BCE (Kuhrt 2010, 2:634). Esarhaddon first made a “show of strength at the border of Egypt” by conquering Phoenicia and the Levant before setting his sights on Egypt (Spalinger 1974a, 298).

Assyria’s successful invasion of Egypt was commemorated on an alabaster tablet from Ashur that reads, “I cut down with the sword and conquered . . . I caught like a fish (and) cut off his head. I trod up [on Arzâ at] the ‘Brook of Eg[ypt].’ I put Asuhili, its king, in fetters and took [him to Assyria]. I conquered the town of Bazu in a district which is far away. Upon Qanaia, king of Tilmun. I imposed tribute due to me as (his) lord. I conquered the country of Shupria in its full extent and slew with (my own) weapon Ik(!)Teshup, its king who did not listen to my personal orders. I conquered Tyre which is (an island) amidst the sea. I took away all the towns and the possessions of Ba’lu its king, who had put his trust on Tirhakah (Tarqû), king of Nubia (Kûsu). I conquered Egypt (Musur), Paturi[si] and Nubia. Its king, Tirhakah, I wounded five times with arrowshots and ruled over his entire country; I car[ried much booty away]. All the kings from (the islands) amidst the sea – from the country Iadanna (Cyprus), as far as Tarsisi, bowed to my feet and I received heavy tribute (from them).” (Pritchard 1992, 290). The details in this particular inscription are historically important because they not only place Taharqa, the ruling Egyptian king, at the scene of the battle but also claim that he was wounded.

Another Assyrian text, known as the Senjiril stela, offers even more interesting details about the battle: “I led siege to Memphis, his royal residence, and conquered it in half a day by means of mines, breaches, and assault ladders; I destroyed (it), tore down (its walls) and burnt it down. His ‘queen,’ the women of his palace, Ushanahuru, his ‘heir apparent,’ his other children, his possessions, horses, large and small cattle beyond counting, I carried away as booty to Assyria. All Ethiopians I deported from Egypt – leaving not even one to do homage (to me). Everywhere in Egypt, I appointed new (local) kings, governors, officers (saknu), harbor overseers, officials and administrative personnel. I installed regular sacrificial dues for Ashur and the (other) great gods, my lords, for all times. I imposed upon them tribute due to me (as their) overlord, (to be paid) annually without ceasing.” (Luckenbill 1989, 273-4).

A picture of Assarhaddon’s victory stele

In approximately 700 BCE, King Sennacherib transformed Nineveh into the Assyrian capital. Although Aššur did not lose its religious and commercial importance, from this point on the empire was no longer administered from the city. Instead, from his throne in Nineveh, the king knew where the peace was maintained, and where it was broken. Messengers relayed signals from fire towers or wrote dispatches on clay tablets.

In September of 655 BCE, Sennacherib’s army set off to the Kingdom of Elam on the Persian Gulf. The Elamites marched to meet them, but they were cut down by the chariots and horsemen of the Assyrians. In their hour of victory, Sennacherib recorded the following inscription: “I cut off their precious lives [as one cuts] a string. Like the many waters of a storm, I made [the contents of] their gullets and entrails run down upon the wide earth. My prancing steeds, harnessed for my riding, plunged into the streams of their blood as [into] a river... With the bodies of their warriors I filled the plain, like grass.”[108] The inscription continued in even more frightening detail, revealing the brutality and cruelty that the Assyrians were capable of. Among the victims was the Elamite king, Teumman, who was beheaded when his chariot turned over as he attempted to flee. The trophy was brought to the Assyrian king, who “slashed it, spat on it, and had it hung as a gruesome trophy on a tree for all to see even while he and the queen enjoyed a banquet.”[109] When the Assyrian king returned to Nineveh, his triumphs were immortalized in room after room of his massive palace – the shocking scenes on clear display to visiting ambassadors from distant realms.

Assyria’s policy towards Israel, the Levant, and Egypt can be viewed from the perspective of a stronger, more militaristic people who used their might to overpower their weaker foreign neighbors, but its policy towards Babylon was a little more complicated. In the periods when Assyria was strong and Babylon was weak, primarily in the Neo-Assyrian period, the Assyrians were often reluctant to take over the city and surrounding region outright, perhaps because Babylon directly influenced culture and was the older of the two (van de Mieroop 2007, 252). By 722 BCE, Assyria governed Babylon directly (Kuhrt 2010, 2:497), but during the rule of the six major Neo-Assyrian kings, approximately 20 transitions of power took place in Babylon (van de Mieroop 2007, 252).

Sennacherib found Babylon particularly troublesome because he was opposed there by a coalition of Chaldeans, Arameans, native Babylonians, and Elamites in 691 BCE (van de Mieroop 2007, 255). A 15 year siege ensued, which ended in the Assyrian destruction of Babylon. The Assyrian annals read, “At the beginning of my kingship, I brought about the overthrow of Merodach-baladan, king of Babylonia, together with the armies of Elam, in the plain of Kish. In the midst of that battle he forsook his camp, made his escape alone, fled to Guzummanu, went into the swamps and marshes, and (thus) saved his life. The chariots, wagons, horses, mules, asses, camels and (Bactrian) camels which he had forsaken at the onset of battle, my hands seized. Into his palace in Babylon I entered joyfully and I opened his treasure-house; -- gold, silver, vessels of gold and silver, precious stones of all kinds, good and property, an enormous (heavy) treasure, his wife, his hare, his courtiers and attendants, all of his artisans, as many as there were, his palace servants, I brought out, I counted as spoil, I seized.” (Luckenbill 1989, 2:133-34).

Sennacherib’s destruction of Babylon did not permanently destroy the great city – in fact, the Babylonians would later play a role in the destruction of the Assyrian Empire – but it did serve to pacify the city for some time. Esarhaddon generally followed the same policy towards Babylon as his predecessors when he gave his son, Shamash-shuma-ukin, the kingship of Babylon. However, Shamash-shuma-ukin rebelled against his younger brother Ashurbanipal, who was the king of Assyria in 652 (van de Mieroop 2007, 255). Ashurbanipal had to campaign for several years in order to pacify Babylon once more, which drained the royal coffers and was ultimately part of the Assyrians’ own demise (van de Mieroop 2007, 255).

The Decline and Rediscovery of Aššur

The Neo-Assyrians were the unquestioned masters of the region for a considerable period of time, begging the question of how they suffered a permanent decline. First, they overreached by expanding their empire beyond the existing network of roads, making administration impossible.[110] More importantly, with their entire worldview based on the idea that there was a constant threat of apocalypse if their armies ever lost a battle, the loss of a single battle had cataclysmic repercussions. That eventually happened; in 612 BCE, the city of Nineveh was conquered by Assyria’s united enemies and the Neo-Assyrian Empire came to its end.[111] The great city of Aššur was also sacked, and a society over a thousand years old collapsed, with its empire totally vanishing.