This statue of Brigid with the children is located on the grounds of St. Brigid's Church in Suncroft Village, just a few miles away from Kildaretown. Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Guerra-Walker.

One February 1, several years before I wrote this, I hosted a small gathering of friends in my tiny living room to celebrate Brigid's holiday: Imbolc. The memory of that cold night, my guests cramped up in a tight circle, is now a signpost in my crazy journey that says, “Here's where things took a serious turn.” Unbeknownst to me, this impromptu collection of curious friends would blossom into the community I would lead and learn from for years afterward. The ritual itself wasn't even the most memorable part of the evening. A close friend who attended that night's rite found out earlier in the day that she was pregnant. She also volunteered to divine the future for us, traditional for an Imbolc rite, and went into a deep trance. After shouting at me, “Where is my book???? Where is my book???,” she then cried out, “Your Seer fights me . . . I shall leave her two!” When my friend came out of trance, she remembered nothing else aside from the number two. When we told her what she had said while in trance, she admitted that Brigid's presence had been overwhelming and she tried to push her away. An image of Brigid came up before her, waving two fingers and flashing a wicked smile. A couple of months later, she learned she was indeed carrying “two.” Although my friend has dark hair and eyes, her red-haired and green-eyed twin girls were born later that year.

Imbolc, Brigid's holiday, is indeed a time of magick and synchronicity. Although the days technically grow longer after the Winter Solstice, it isn't until early February (or August, if you are in the Southern Hemisphere) that this change is noticeable. In the ancient Celtic world, the lengthening of days meant far more than warmer days and later sunsets. It was a sign that the most dangerous point of the year had passed. Winter was a time of illness, hunger, and death. Although the ground was cold and often the snow still present, the first stirrings of spring arrived with Imbolc, and with them, the promise of health, food, and life restored again.

Celtic holidays marked the turns in the agricultural cycle. Druids, as the keepers of time, were the curators and preservationists of these traditions and rites. The great fire rites at these holidays stood as the main points in the circle of the year. The following descriptions illustrate practices in Celtic Ireland, but different versions of these rites were found all over Celtic Europe. Bealtaine, in early May, was the beginning of summer. Cattle were driven to pasture and rites of fertility took place. It was the optimal time for would-be mothers to conceive. Lughnasadh, at the beginning of August, focused on the harvest Goddess Tailtu's sacrifice of clearing the forest for the corn and crops to grow. A series of games akin to the Greek Olympic games was held in honor of Tailtu and the first collection of harvest produce. Samhain, in early November, marked the end of the harvest season. All field goods had to be collected before the frosts would set in. It was the last point of bountiful fresh food for the year and also a time of death. Cattle not fit to last the winter were slaughtered for food and to preserve resources for healthier livestock. Imbolc was celebrated roughly around dates now called January 31 through February 1, as Celtic holidays were celebrated from sundown to sundown. Imbolc was marked by the time when the cows and sheep would begin lactating again, the first signs that winter was on its way out of the land. The milk products would have been some of the first items of fresh food the people would have had since early November. Women who conceived at Bealtaine delivered their babies around this time. The world was coming back to life. Through the lens of the harvest, Samhain was an end. Imbolc was a beginning.

Early February may seem like a very early spring to much of the Northern Hemisphere, particularly in northwestern Europe. Yet roughly 7,000 years ago, the climate of the Celtic region was much more akin to the contemporary Mediterranean region. February 1 was likely a much warmer time, one suitable for crop planting. If this is the case, the significance of the Imbolc holiday may be as old as the Boreal Period, which took place 7000–5000 B.C.E.

In the United States, February 2 is Groundhog Day, marking the return of the furry little animal from its underground bunker, which is one of North America's first signs that the winter is going to end. In Europe, the earliest signs of spring included the snakes arising from the ground (in areas other than Ireland where snakes have never inhabited), or animals coming out of hibernation. For the Celts, the most important sign of Imbolc was the lactation of the cattle and sheep. The word “Imbolc” derives directly from Imbolg or Oimelc, words meaning “of milk” or “in the belly.” Celtic economy was heavily based on farming, and dairy products were a main food staple. The role of ewes and cattle production was so important to the functionality of the community that the entire agricultural system and important aspects of the religion centered on their ability to produce. The change in the Earth Mother, while she could be brutal during the tenuous parts of the harvest and dangerously unforgiving in the winter, was most welcome in her springtime form. Brigid the Exalted, who was given Imbolc as her Patron holiday, indicates that this may have been the most important point in the Celtic year and certainly the most beloved.

When the land darkens at Samhain, when the veils between this world and the Spirit are at their very thinnest, the Cailleach, the Old Hag of Winter who destroys all and brings darkness to the land, kidnaps Brigid from her place at the great Harvest Fires and whisks her across the chilling landscape. She stows Bright Brigid away in her Hag's fortress of Ben Nevis. There she remains, a prisoner of winter until Imbolc eve. At this time, Brigid's brother Oenghus, the God of Eternal Youth, will ride from the Otherworld on a white horse to rescue her each Imbolc eve. On her release, the icy Hag chases the pair across the landscape, raising great storms to thwart their escape. Brigid pushes back against the old Hag with her fiery arrows of the sun, and turns the Cailleach back to stone. The light returns, the cows give milk, and the new babies cry. Spring once again returns to the land, and so it continues each Imbolc from now until the end of time.

—INSPIRED BY TRADITIONAL TALE

Like the Grecian myth of Persephone and Hades, the space between Samhain and Imbolc is Brigid's own journey into the Shadow world. The earth is quiet, cold, and resting. This myth, in various forms, may be thousands of years old. Brig as “The Lady of Springtime,” is the spirit of the early spring whose rule alternates with that of a wintertime Goddess. Cailleach may simply mean “old woman” as in Old Woman of Winter, the way other vernacular refers to the cold months as “Old Man Winter.” Depending on the location, the Cailleach was associated with natural wisdom, perhaps the storytelling by the fires, harvesting, and preservation, but also wild and wicked storms that would ravage the land every year.

Other myths talk of Brigid as both herself and the Cailleach, having two faces—one being young and comely, the other old and haggard. At Imbolc, the Cailleach, transforms into Brigid by drinking from a sacred spring before dawn:

On the eve of Imbolc, the icy Winter Hag, the Cailleach, travels to the forest of a mystical island, where within lies the Well of Eternal Youth. At dawn's first light, the frigid Goddess drinks the water that bubbles in a crevice of a rock, and is transformed into Brigid, the Goddess of Spring and life who strikes a white wand upon the earth to make it green again.

—TRADITIONAL TALE

Still other myths describe Brigid as dipping a white wand or breathing life into the mouth of winter, waking the sleeping earth, and bringing tears to Winter's eyes (a symbol of the thaw), and ushering along the sounds of spring. The white wand may be a stick of birch, or it could be a symbol of the blinding late winter sun. Some stories say that cold trembles for its safety on Imbolc and flees for its life on St. Patrick's Day in mid-March, as spring firmly takes hold:

Bride put her finger in the river

on the Feast Day of Bride,

and away went the hatching mother of the cold.

And she bathed her palms in the river

on the Feast Day of Patrick,

and away went to the conception of the mother of cold.

—ALEXANDER CARMICHAEL

Like the forge's fire or the energy welling up from the Bard's song, Brigid the Spring Goddess breathes life back into the cold, sleeping land. Like the Forge, the Wells, or the Bard's abilities, Imbolc reflected magick. It marked the tide of easier, gentler days to come when planting was possible and food was plentiful. True to her nature as Fiery Arrow, the sun that seems to abandon the world for a time gently returns to stir the sleeping and warm the frozen ground. Streams and wells will soon begin to trickle, their healing powers abundant once again.

Brigid has also been described in relation to the different cycles as the Earth Mother. At Bealtaine, she is a young woman on the threshold of marriage with the elements. At Lughnasadh, she produces the harvest. Come Samhain, she assumes the form of the Winter Hag, but at Imbolc she is the infant Goddess born again. Be it title, name, or season, Brigid is most powerful at the start of spring. In another version of the Threshold Rites, a sheaf of wheat from the Samhain harvest was placed outside doors of homes on the eve of January 31. Some believed that the Goddess was present in the sheaf in her winter Cailleach form. Upon Imbolc, the sheaf becomes the infant Goddess Brigid once again, marking the fragile beginnings of the new agricultural cycle. When sowing time comes again, the grain from the final sheaf was then mixed with the new seed, to nurture the earth again, encouraging the next harvest, and ensuring a cycle of life and rebirth.

She who put beam in moon and sun,

She who put food in earth and herd,

She who put fish in stream and sea,

Hasten the butter up to me.

Pray Brigid, see my children yonder,

Waiting for buttered buns,

White and yellow.

—TRADITIONAL IRISH PRAYER FOR IMBOLC

In the Threshold Rites, the old harvest was dismembered to become the new harvest, the protector, and the domestic helper. Other rites called Brídeog included the human-shaped fixture of rushes, sometimes dressed as a young girl. The Brídeog was carried from house to house by a procession to bless the entire community and collect money for charity or the local church. These were Catholic rites conducted in honor of St. Brigid, but the connection to the Harvest Goddess and the Earth Goddess born again is unmistakable.

In a pantheon of so many harsh characters, it's curious to come across one who is as gentle as Brigid, at least in the light that Imbolc paints her. At Imbolc, Brigid is the calming voice that says, “It's okay to come out, now!” Just as her power infused previously raw ore into invaluable tools, so does her return at Imbolc transform a barren world into one fruitful and bountiful. She is the Smith on the land, heating the cold soil to life again. She is the Bard that entices the birds to song and the Well that brings health and renewal to the people. The ancient Celts knew the Earth Mother could be wicked and cruel. Perhaps they saw Imbolc as a time when she could also be kind.

Brigid's aunt, Fainche, had very long been barren and came to Brigid for a miracle. Brigid fasted three days in the church at Kildare and an angel came and said to her: “O Holy Brigid, bless thy aunt's womb and she will bring forth a distinguished son.” Brigid ran to her aunt and prayed vigilantly over her womb, until Fainche felt the miracle stir within her. Fainche had a son that year, Colmán, and went on to have a further three: Conall, Eogan, and Cairpre.

—TRADITIONAL TALE

Early spring is not always kind. The rain, sleet, and mud are the byproducts of transformation into spring. But Imbolc and its rites are a reminder that gentler days are just around the corner. Likewise, motherhood may be sometimes imagined as a peaceful existence. The image of a quiet mother rocking a sleeping baby is the ideal and certainly a piece of the picture, but the whole embodiment is wrought with work, fragmented sleep, and worry for the children. The process of the early days of spring, like birth, is tumultuous. Fluctuating weather patterns, thaws that bring floods, and storms brought by the mix of warming air on a cold world are a normal part of the Imbolc process. Still, this period of the year was optimal for the Celtic birthrate. Pregnancies begun at Bealtaine allowed for the mothers to work through the pivotal harvest season. They would experience the least mobile part of their pregnancy during the darkest months of the year, when there was less work to be done and the community could collectively focus on rest. Birthing in early February, in time with the return of the dairy products, would mean well-nourished mothers and babies could thrive better in the warmer months, cared for by communities with access to the most plentiful food sources.

Fertility Goddesses were most often honored at springtime shrines, the mysteries of birth combined with the abundant earth vital to life. Later, when the shrines supported the Roman Gods, nursing mothers wore amulets of the Goddess Sulis, who was frequently interchanged with Brigantia, to encourage lactation. Perhaps because of the springtime connection, and because of the earth once again producing, Brigid became synonymous with motherhood—both in having her own children with Bres and becoming the midwife, literally ushering new life into the world.

Brigid's father, Dubthach, the Chieftain of Leinster, drove his chariot along the road with his bondmaid, Broicsech, who would one day become the mother of Brigid. They passed and stopped inside the house of the Druid Mathghean who, during their visit, prophesied that the bondmaid would give birth to a child of great renown. In hearing this story, Dubhthach's wife became enraged with jealousy and sold the bondmaid to a Bard who in turn then sold her to a Druid of Tirconnell. By this time, Broicsech was heavily pregnant with Brigid. This Druid gave a great feast to which he invited the King of Conaill whose wife was also expecting a child. The Druid foretold that the child would be born at sunrise the next day, and neither within the house nor without and would be greater than any other child in Ireland.

That night the Queen gave birth, but her child was dead. At sunrise the bondmaid, Broicsech, bore a child while standing with one foot inside the house and the other outside of it. Broicsech's child was then brought into the presence of the Queen's child who, miraculously, was restored to life. This Druid travelled with Broicsech and her baby into Connacht when, in a dream, he saw “Three clerics in shining garments,” who poured oil on the girl's head and thus completed the order of baptism in the usual manner, calling the child Brigid.

—TRADITIONAL TALE

This Christian myth of St. Brigid summons Brigid's roots as a springtime Goddess. Even the King and Queen, the sovereign beings of the land, were not immune to the tides of death. Their child, symbolizing the new harvest, is without life until the presence of the infant Brigid, the fledgling Spring Goddess, breathes life anew. Brigid's mother, straddling the doorway as she gives birth, is a reminder of Brigid's place in both the spring world of the living, and the winter realm of the dead. In the final part of this myth, three clerics, similar to the wise men visiting the infant Jesus, reveal Brigid's level of importance to Celtic faith, even in the transfer to Christianity. Like Jesus, whose presence in the Christian faith restores the world, Brigid is renowned and prophesied light and life to the world, but through her embodiment of the awakened earth.

While her Celtic Goddess myths reveal her as a mother herself of three sons, St. Brigid was most often a midwife or a foster mother to Jesus. This may be in line with some Christian theologies that put sanctity on the idea of a Virgin, which would be rendered impossible for Brigid had she been a mother herself, as only the Virgin Mary could give birth without having had intercourse. The midwife secured Brigid's legacy as a fertility being. In addition, she was also considered the midwife to the Christ child's birth and, in some stories, even his foster mother. In the myths from this region, the role of the foster mother was on par with (and in some cases surpassed) the birth-mother role in importance. The idea of the Irish St. Brigid being a midwife in a story based in the Middle East may seem rather absurd, but this was a way in which the exalted Goddess would carve her way in the new religion as Christianity settled in, taking no less than the most important place next to the most important character in the new religion.

Brigid was a daughter of poor parents. She worked as a serving maid at a tiny inn at the tiny town of Bethlehem. It was a torrid time—a great drought had struck the land. The master of the inn went away with his cart to get water from a far distance, entrusting Brigid to watch the inn. He left her a serving of water and portion of bread to tide her over until his return. Because of its scarcity, the master ordered Brigid to share no food or drink to anyone and to not extend shelter until he returned with provisions.

Not long after the master left, two strangers came to the door and asked for a place to stay for the night. They were hungry and weary and in desperate need of water. The woman was heavily pregnant and while Brigid could not risk giving them shelter, gave them her bread and water. The couple ate at her doorway, thanked her kindly, and went along their way.

Brigid was saddened at the couple's condition—particularly for the young woman in her time of need, and regretted she could not give them shelter from the heat or any more water or food than what she gave them. Out of concern for the couple, she ran out into the late afternoon sun and pursued them for hours, until it was very dark. Just then, she saw a golden light shining from a stable door. She ran to the stable and saw the woman, who was the Virgin Mother, about to give birth. Brigid aided the woman, delivering the child who was Jesus the Christ, the son of God who had come to Earth, and the couple was Joseph and Mary. Brigid put three drops of water from a nearby spring of pure water on the baby's forehead in the name of God. The world rejoiced and it is because of this that Brigid is known as the Aid-Woman of Mary or Foster Mother of Christ. Still others call her the Godmother of the Son of God and yet others call her the Godmother of Jesus Christ of the Bindings and Blessings. Christ himself is known as the Foster Son of Bride, the Foster Son of the Bride of the Blessings, and sometimes even the Little Fosterling of Brigid.

—TRADITIONAL TALE

Few saints would be able to get away with being credited for delivering or even rearing the Christ child as the Foster-Mother title would suggest. More remarkable still is that the baby Jesus could possibly be titled the “Little Fosterling of Brigid,” which insinuates a greater power credited to Brigid than even the Son of God, himself. There may be a cultural history component to this telling. As the midwife ushers the new babies into the world, Brigid the midwife ushered the new religion into the land.

Reflection: Change is necessary. All things must grow and adapt or else perish. This is how our vulnerable species survived over hundreds of thousands of years. Likewise, we as individuals must adapt to cultural shifts and changes in our own lives or face death within ourselves. When changes are imminent and uncomfortable, like the discomfort in the early time of spring, how can we adapt ourselves so that we too can grow? If Brigid can adapt from the Earth Goddess in her indigenous religion to the Exalted Foster Mother of the Great God of the New Religion, what roles can we carve for ourselves when great and unavoidable changes take place around us?

Brigid's aid was summoned by laboring mothers when their delivery time was near. In areas of Scotland, Brigid was petitioned as the Woman on her Knees, or “It was Bride fair who went on her knee,” describing the midwife's position when assisting at a birth. In the Scottish Highlands and Hebrides, it was once traditional for women to give birth while kneeling on one knee. At the same time, the midwife or a midwife's assistant would stand on the doorstep with her hands on the door jambs and softly speak the following:

Bride! Bride! Come in,

Thy welcome is truly made,

Give thou relief to the woman,

And give the conception to the Trinity . . .

The mother might appeal directly to Brigid, herself:

There came to me assistance,

Mary fair and Bride;

As Anna bore Mary,

Mary bore Christ,

Without flaw in him,

Aid thou me in mine unbearing,

Aid me, O Bride!

As Christ conceived of Mary

Full perfect on every hand,

Assist thou me, foster mother

The conception to bring from the bone;

And as thou did'st aid the Virgin of joy,

Without gold, without corn, without kine,

Aid thou me, great is my sickness,

Aid me, O Bride!

Logically, the doorway of the home makes sense for a birthing mother. The position of being on the knee allows for gravity to bring the child into the proper birthing position, and the doorway could be used as support to keep the mother upright. Perhaps for this reason, the threshold of the home was a sacred place. Symbolically, it represented the sometimes perilous threshold between death and birth. Imbolc Brigid not only brought the light back to the world at the springtime, she brought in human life into the world often at this same time of year, ushering women and children through the potential dangers of the threshold of birth.

While researching this book, I came across enough Imbolc traditions to fill a tome. In the early twentieth century, the Irish Folklore Commission issued a questionnaire about the various rites called The Feast of St. Brigid in an attempt to record the traditions. The results filled nearly 2,500 pages of manuscript, marking Brigid as a saint whose range, number of customs, and stories numbered greater than nearly any other saint. These few paragraphs are merely a scratch on the tip of that Brigid iceberg. But if one could find a single word to encapsulate these practices, it would be “Welcome,” Imbolc welcomes Brigid and, through her, welcomes light, spring, and life.

Like a female Santa Claus, Brigid was believed to visit all the houses on Imbolc eve. When it was time to turn in for the night, the hearth ashes would be spread delicately and smoothly over the coals. The ashes were meant to be Brigid's bed, hopefully comfortable enough to suit her liking and earn her blessing when she would come through to lie down to bed for the night. If the ash carried imprints the next morning, Brigid had blessed the house. If the ashes had been found undisturbed, then Brigid had skipped the house and misfortune may be present. A sacrifice, such as the chicken blood at the crossroads, might have been necessary to re-earn her favor.

Another Brigid Imbolc rite involved a silk ribbon or a cord. On Imbolc eve, such a piece would be measured and placed outside, either on the threshold or windowsill. Come the next morning, the piece would be measured again. If it were deemed longer in the morning than the night before, luck would come about over the course of the following year. If it had seemed to shrink, misfortune was evident. The idea was that Brigid had blessed the ribbons when she passed, causing them to lengthen. As in the ashes, if the cord did not grow or had seemed to shrink, Brigid was displeased. Blessed cords or ribbons were ever after preserved as healing amulets, particularly as headache remedies.

One beautiful story I read involved an old woman who lived in a remote area of Ireland in the nineteenth century. She owned a shawl that she had treated as a Brigid ribbon for fourteen years. She claimed that any time she requested something of the shawl, it was granted by the grace of St. Brigid. One such story was about a time her cow struggled in labor. The calf wouldn't come. It took several men to hold the cow down to assist, yet the calf would not budge. After hours of watching the cow labor, fearful for the life of the calf and its mother, the woman fetched her shawl and shook it over the cow. She then went onto her knees and prayed fiercely to Brigid. Ten minutes later, she claimed, the calf finally came through. Both mother and calf were fine. The woman later shook her shawl over a childless woman who desperately wanted a family, and soon after the woman had a child.

In some areas of Ireland, a little wooden branch was burned in a domestic fire on Imbolc eve. When the fire was quenched, a soot cross was marked with it on the arms of family members. This may have similar resonance to the burning sacrifices of millennia prior, but its later meanings were certainly connected to life and growth. Fires at Imbolc had significant associations with fertility as well. Ashes from local fires were strewn upon the fields. This act was vital in enhancing fertility of crops, in both a ritualistic and practical context. The intent was Brigid's blessing, which might have manifested through the ash enriching the soil. Likewise, fertility of livestock would have been of dire importance. Imbolc was also a time in which cows, sheep, or other livestock were blessed in protective rites. The Brigid who served as the first abbess of Kildare, formerly a Chief Druidess, was probably involved in ceremonies to invoke Divine help in the blessings of crops, animals, and certainly human mothers as well.

Brigid walked along the road one day and heard a low, suffering moan from a hut. She followed the sound and entered. There she found a dying tribal chieftain, still devoted to the Gods of Old. Brigid told him of her conversion to the new faith of Christianity and wished to share the powers of her new God with the dying man who otherwise was quite alone in his last moments. The dying man would not listen and insisted she seek a Druid to come to his aid. Brigid knew there were no Druids left within a two-day ride. The ailing chieftain would die without a word spoken in honor of his spirit, no rites performed in honor of his death. She sat with the man in silence for many hours, dabbing his brow, holding his hand, trying to offer some comfort. The chieftain began to despair. Would there be no one to speak to the Gods of the Sun and the Water or the Spirits of the hills to notify them of his passing? Would he walk the earth for all time as a wailing, confused ghost? As the sun set and the chieftain's breathing thickened and weakened, Brigid ran across the dusky hillside and desperately pulled up rushes, weaving them into a hasty cross. She hurried back to the hut, showing the cross to the chieftain, and described the sacrifice her new God Christ had made and the eternal life He offered after death. In his last waning moments, the old chieftain recognized the Gods of the Sun in the sun-shaped rush cross, felt the soothing River Goddess in the description of Christ's healing. He knew the sacrificed Christ was the same as the slain Corn Gods of all the Harvest Rites he had ever known. Through Brigid's Christian rite, his soul would know peace and eternal reunion with all those who had gone before him. He allowed her to pray to her God for his soul, and sing a sweet hymn. He clutched the reed cross until life left his body, and when the time came for his burial it remained pinched between his fingers.

—INSPIRED BY TRADITIONAL TALE

I did expand upon this common myth of St. Brigid and the construction of the St. Brigid's cross. Like many Christian stories, it involved a last-minute conversion of a dying person after simply laying their eyes upon the symbol of Christ. Even as a Christian child, I had a hard time wrapping my mind around these stories—how could a simple shape with barely an explanation cause such great change in a person's heart? Now, as a Neo-Pagan, I appreciate the story of St. Brigid and the Pagan Chieftain as a reminder that we can change the world with only what we have at our fingertips. In telling it for this book, I sat deeper with what might have been going on during the time of the chieftain's passing, why he might have been open to accepting the new faith at the last moments, and what he could have seen in the cross that gave him so much comfort. I also sat with Brigid's compassion and her relentless resolve to be there for the man in his last moments alive.

Reflection: Look all around you. What could you use, within your grasp, that could change the world? For me, it's my computer to write these words. It is also my phone to call someone and let them know they are loved. It is my window, which I can wave through to passersby on the street. What is available to you, right now, that you could use to change the world?

The St. Brigid's cross is a prevalent image in contemporary Celtic Christianity and evermore a fixture in the Neo-Pagan revival. It is traditionally made from rushes, although it is quite easy to find representations in other forms. I wear a pewter cross and our home has a brass cross in the entryway. Traditionally, the rush crosses were picked—not cut—on Imbolc eve. In some areas, the person gathered the material for the crosses in secret. Sometimes, rushes were collected by a group of people, the gatherers praying quietly to themselves without speaking to one another until they reached home. Rushes might be kept from Palm Sunday (taking place the Sunday before Easter) and woven into crosses at Imbolc of the following year. Sometimes, the maker might insert grains of corn between the rushes.

The cross's shape is believed to be a derivative of sun symbolism, its very nature hinting at Pagan roots. The four equal points are slightly off center, which gives the eye the illusion that the cross could turn of its own volition, and speaks to the turn of the seasons and sun's cycles. The cross has also myths and rites of healing attached to it. It was believed to promote fertility of humans, animals, and crops as well as protect the home and its inhabitants from illness, hunger, and fire. They were often nailed to the beams inside the home or over the doorway entrance to the house. As the potato crop became the centerpiece of Irish agriculture, the cross was sometimes fixed to the roof beams with a wooden peg on which a potato was impaled, encouraging a rich harvest. A cross might be placed onto a basket of potatoes and taken to the fields at planting time to include Brigid's blessings on the crop. Frequently, the previous year's crosses were burned at Imbolc and their ashes were buried or scattered over the land. This is believed to be a direct link to rites of burning at Lughnasadh, where a portion of the harvest was re-dedicated to the Gods. In more recent years, the cross has been called simply “lucky” by many.

The St. Brigid's cross was often used to bless the Imbolc meal. Sometimes (as in the Threshold Rite in Chapter 6) the cross served as a placemat for the food. Crosses then took their places over doorways, mantles, or were nailed to the crossbeams of the house or stable to ensure a year of health and plentiful food.

St. Brigid save us from all fever, famine, and fire . . .

—AN IMBOLC PRAYER

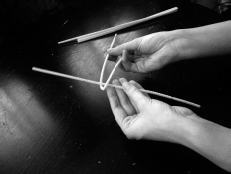

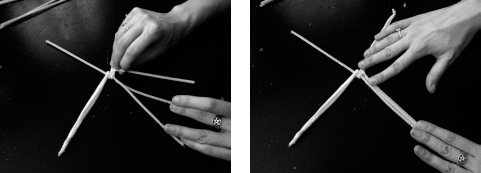

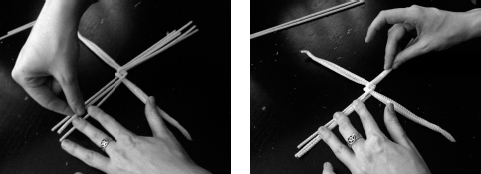

To make your own St. Brigid's cross, you can gather rushes, but wheat stalks, grass, or other reeds will be suitable too. If you are using dry or brittle pieces, you may need to soak them in water to soften them. They can also be made from pipe cleaners or wires, which I have used below:

A traditional blessing from some parts of Ireland when hanging a St. Brigid's cross says, “May the blessing of God and the Trinity be on this cross, and on the home where it hangs and on everyone who looks at it.”

A Neo-Pagan version for Brigid may be said, “May Brigid bless and keep this home. May the blessings ever grow. May all who cross my threshold know always the promise of spring. Blessed be this cross, Brigid! Blessed be my home!”

Divination was a favored pastime of Imbolc, possibly because the days were primarily spent around the fire keeping warm, passing time while the tides of Imbolc did their work on the land and the planting could truly begin. If you have a fireplace, replicating the hearth and ashes working could tell of the tides to come throughout the year. Smooth the ashes over the coals and check them in the morning. Do the ashes look like there might have been feet stepping on them? If so, Brigid has blessed you! If you do not have a fireplace, you can do what I do and leave a blanket and pillow by the radiator. Take a peek at the blanket the next morning and if it's been disturbed by something other than a pet; maybe it was Brigid who came by! If your ashes or blanket were not disturbed, it might be a telling of a tougher year to come. Make notes over the years of what you see and the events that followed.

As in the rites of old, leaving a Brigid ribbon out on Imbolc can still be an act of divination or a charm for healing. The piece can be actual ribbon or a strip of cloth, a sash, cord, or even a shawl as the lady in the story used. For best results, the piece should be long enough to wrap around the average person's head three times and tie into a knot. My coven cuts pieces of green, gold, or red cloth. On Imbolc eve, we light candles to Brigid and wave the cloth pieces over the flame nine times. I don't know if waving over the flames is part of the original rites, but it certainly sets the tone nicely in contemporary ones. Leave the cloth out by your window or, if you're able, on your front doorstep. Be sure to set out a nice cup of tea and a treat for Brigid as she passes by on Imbolc night. Measure the cloth before setting it and measure it again in the morning to see if it lengthened or decreased. A cloth that has seemingly lengthened indicates good luck to come. In this case, keep your Brigid ribbon for healing work. If you think your cloth has decreased in length, it may be time for meditation or reflection to be aware of any potential nasty luck ahead.

Traditionally, the ribbon is rubbed or drawn around the patient's afflicted area three times. Brigid's ribbons are best known for their effects on headaches, but also for toothaches, earaches, and sore throats. Members of my coven swear by them for alleviating anxiety or menstrual pain. When applying the ribbon, say the following invocation:

In the name of the Poet, the Smith, and the Healer,

Brigid make you whole again.

Knot the ribbon around the painful area. For best results, use the same ribbon each Imbolc, which will increase its potency.

(A similar version of this spell can be found in Chapter 10, for decision making.)

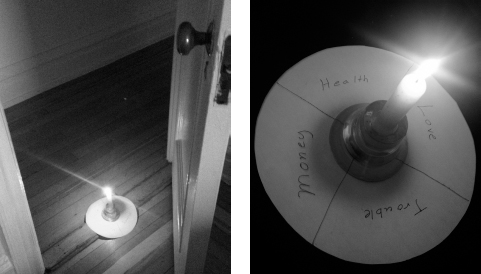

Take a paper plate and write or draw images of the following things:

Money

Love

Trouble

If there are other things you hope to come to you in the next year, you may add those as well. You will want to give each item an equal section on the plate.

Set a red or yellow candle in the middle of the plate, and place the plate on a flameproof setting in a doorway. As the candle burns down, take note of where the wax spills. Lots of wax in that area indicates what you will have abundance of in the next year, for better or worse. Lack of wax indicates just that. Take a picture or save the plate and, at the following Imbolc, make note of how much came to manifest and how.

As part of your Imbolc rite, you may want to include some sort of ritual cleansing—on yourself, your home, or both. This period of the year has traditionally involved some sort of cleaning, be it the fields for planting or a postpartum blessing on a new mother. The idea of spring cleaning may have its roots in Imbolc practices or others of a similar kind from different regions. Clearing and cleansing practices restored health and hygiene of the land, body, and home, but also symbolically restored a boundary between the forces of good and evil. The following rites are suggested for either one person or a group at Imbolc. Naturally, due to the actions involved in the second ritual, it is better recommended for a group but either can—and should—be augmented, enhanced, or changed to suit the needs of the practitioner(s).

Bowl of cleansing water (see Chapter 3 for suggested concoctions)

Three white candles

One yellow candle (do not use dripless candles)

A small food offering—preferably something sweet such as a cupcake or a cookie

Before beginning your Imbolc rite, reflect on recent events in your life: blessings, lessons, growth, and more. Create a space of comfort—perhaps with a cozy comforter and a cup of tea. (As always, if you live in an environment where there is little or no privacy or quiet, don't be afraid to make use of your bathroom as sacred space.) Focus on challenges that have come up in the space between Samhain and Imbolc, particularly any challenges you'd like to leave behind. Focus on what things you really wish to see come into your home, health, work, or self. Try, as best as you are able, to envision when throughout the months between the present Imbolc and the following Samhain that these things could happen (e.g., increased money after tax time, a new exercise routine when the weather warms, travel during the summer, a return to school in the fall).

Set your space for ritual with the four candles in holders, unlit, in a circle with the bowl of cleansing water in the middle. If you are in a region where snow is present, consider adding a lump of clean snow to your water just before beginning the rite. When the challenges and desired blessings are firmly in your mind, light the three white candles and let them burn for a while, but do not light the yellow one yet. Draw into your mind the vision of the Cailleach, the Winter Hag. Call upon her aloud or in your head:

Queen of Ice, Queen of Stone,

Hear me from your Frozen Throne,

Be here, be here, be here now!

As you chant or meditate on the words, envision her hair of snow, her skin of stone, and her eyes of ice, or however she appears to you. When you can see the image of the Winter Hag as firmly in your mind as you are able, cease the chant and begin to recount the challenges you've faced over the last few months either in your head or aloud. Next, tell her why you no longer want these things to hold you back. Then, listen. Listen to the words of the Winter Hag. Why were you faced with such challenges? Does she know? What words does she have for you?

When you are ready be released from these things, begin to chant or meditate the following:

Brigid has come! Brigid is welcome!

Brigid has come! Brigid is welcome!

Continue to chant until you can see or feel Brigid and her hair of sunbeams and long green cloak replace the space of the Winter Hag. Light the yellow candle. Declare aloud or in your head what you want to be free from, such as, “I release myself from stagnation in my career!” “I release the anger and pain at my ex!” “I release impatience with my children!” Allow the dripping wax of the yellow candle to extinguish the flame of the white candles.

Sit with the burning yellow candle for a time, fixating on the image of Brigid in your mind. Tell her, aloud or in your head, what you wish to see blossom in your life over the spring, summer, and autumn. Then, as you did with the Cailleach, listen to any words that may come from Brigid, herself.

Finally, wash your face, the top of your head, and neck with the cleansing water. If you wear jewelry daily, wash that as well. If there are specific possessions that remind you of your troubles or troubling time, immerse them in water (if they are things that can be immersed—stones such as opal or selenite cannot be submerged) or simply flick some of the water over them if total submersion would damage them. Consider then changing your clothes as a symbol of putting on a new face, even if they are not new clothes. If you are able, burn the candle in a safe place in the center of your home—where you can see it, of course! No flames should be left unattended! The rite has concluded. Leave the sweet treat for the night on the windowsill. The sweet on the windowsill is a very old Imbolc tradition, one in which a sheaf of hay was also left for Brigid's cow, as Brigid was believed to travel the countryside with a bovine companion. Traditionally, it was expected that the poor or hungry would take the food during the night, keeping with the spirit of Brigid's aiding the poor. If this aspect speaks to you, consider taking an extra step in leaving the food where you do believe a hungry person will find it or simply drop off a food donation at a local pantry or soup kitchen.

Use the remaining water as a floor wash or sprinkle in the corners of your home to cleanse and renew your home.

After your rite, pamper yourself and relax for a bit. You'll want to be restored to meet all of the changes you wish to manifest!

Imbolc rites have involved community efforts for centuries. While some rites, such as the parading of the Brídeog, involved the entire community, many of the rites were private and focused on the family. In using this format, the following ritual can be performed with a group—be it a working magickal or spiritual group, friends, family, or a combination. Very young children might not fully understand the significance of the ritual, but could certainly be a part of it and enjoy the family time.

Cleansing water (purified or boiled water with a pinch of salt).

One large candle and a collection of tea light candles—one for each person in the group.

A bowl of earth or a decent-sized stone, perhaps one that needs a hefty fist or two hands to carry, but it doesn't need to be larger than that. This shouldn't be a gemstone or something decorative. It should come from a natural setting, such as a forest or field, or even a park.

A green or yellow cloth or shawl.

Cakes, cheese, or a potluck meal to share. Again, dairy products are most sacred to Brigid, but no matter the case, you'll want to be mindful of dietary restrictions and have appropriate options for your guests if they cannot consume dairy.

Set three stations on separate tables or in separate areas—one for the water, one for the candle, one for the stone. If need be, all three stations can be set atop a long table. If possible, the stations should be set with items reminiscent of Brigid or springtime. Take liberties and be creative with how this is displayed.

One person should be selected to act as Brigid who will take the green or yellow cloth/shawl, and hide either outside or in the next room. This person can be of any gender. Some traditions had a young woman play this role; others had a man playing the role of “bringing Brigid” to the room. Choose the person you feel best embodies the energy of Brigid, regardless of their gender, and let them choose whether to “be” her or to “bring” her. When the Brigid player is ready, they will knock three times on the door or entryway to the room.

Group: Who knocks there?

Player: It is I who touched the river and chased away the cold!

Group: Who is it who chased away the cold?

Player: It is I who chased the Winter Hag away!

Group: Who is it that chased the Winter Hag away?

Player: It is I who came with the wand, who breathed the breath back to the land! It is I! It is Brigid! It is I! It is Brigid!

One Member of the Group: Go on your knees, open your eyes, and let Brigid in!

Remainder of the Group (some may choose to kneel): She is welcome! She is welcome!

The Player enters the room or house with the shawl or cloth on their head or in their arms and the group exclaims: It is Life! It is Health!

All hug, kiss, and welcome Brigid.

The Player walks to each station. At the stone, they tap it and say, Winter Hag be gone and stay gone! You who have turned the land to ice, now you turn to stone! Spring has come throughout the land!

Group: Spring has come throughout the land!

Player walks to water: Water, you who have once been ice, now you thaw and warm again. Spring has come throughout the land!

Group: Spring has come throughout the land!

Player walks to candle: Child of the sun, perpetual flame! Come back to earth! It's spring again!

Group: Spring has come throughout the land!

The following should either be read by the person embodying Brigid, or it can be split into sections and read by members of the group. (The poem for this rite was written by Nanci Moy.)

Cailleach

Winter Crone

Shakes out her downy comforter

Snow covers the land in sleepy silence

Cailleach wanders

Tap taps her silvery rod

Crystalline webs stretch across streams

Stilling ripples, frosting breath

Cailleach nears the sacred Well

Sighing, sips deeply

Healing waters wash away the years

Brigid flames forth

Maiden melts Crone

Brigid

Bright One

Spreads her mantle wide

Sees peeking snowdrops ’neath suckling lambs

Brigid strides forward

Blesses brats girdles crosses dolls

Drip drip the icicles on trees

Into pools lakes streams rivers

Brigid sings with the lark

Ripples with the waters

Inspires all with crafty wisdom

Blesses hearth

Heart of home

Brigid is Come!

Brigid is Welcome!

Group members, individually, visit each station. At the Stone, they bid farewell to winter—to troubles or challenges of the previous season, or give thanksgiving for boons or blessings. At the Water station, they cleanse themselves—either washing faces or hands or flicking water around themselves as a way of cleansing the spiritual body that surrounds their physical one. At the Fire station, they place their hands around the flame as a way of allowing the sun's rays to nurture their new spring self.

While this is happening, chant or song is helpful to encourage the spirit of new spring. The albums A Dream Whose Time Is Coming produced by the Assembly of the Sacred Wheel, Chants: Ritual Music from Reclaiming and Friends by Serpentine Music Productions, or La Lugh: Brighid's Kiss by Gerry O'Connor and Eithne Ni Ullachaine have lovely selections to use for this portion of the rite. Websites can be found in the bibliography.

After each person has visited each station, it is time for food, divination if possible, or sharing of stories, experiences, or reflections. A small portion of the food should be set aside in honor of Brigid. The water can be sent home with guests in bottles so that all can use it in renewing their homes.

I receive a lot of requests for baby blessings. They are sweet and fun. If you would like to perform a Brigid-inspired blessing for a baby, the following may prove helpful. My experience has taught me that short and simple but heartfelt rituals for children are the way to go.

Set the space with a candle, a small bowl of water, and a small bowl of soil. Parents and other guests, if attending, should chant Brid is Come! Brid is Welcome! several times to set the space.

Anoint the baby's forehead with drops of water on your fingertips, making a thrice-circular motion. Say the following: May Brigid grant you Health.

Wave the candle three times before the baby and say: May Brigid bring you passion.

Taking a wet finger, dip into the soil and leave a tiny mark of earth on the baby's forehead. Say: May Brigid bring you the strength of the earth, and may you always have a solid path to walk on.

Parents and any other guests attending may wish to impart their blessings on the baby at this point.

Conclude the rite by saying: May Brigid bring you all these things and more, enough to fill the sea. May Brigid bless each step you take from the day you first begin to stand. Blessed be, Brigid! Blessed be Brigid upon you!