At Whitsuntide in May 1839, the mill workers of Manchester enjoyed a rare holiday from the toil and noise of the factories, savouring the fresh air while walking in the countryside. Afterwards, the Bartons invited their friends the Wilsons back to their home for tea. The two families wended their way through the maze of narrow streets into the London Road slum district and crowded into the Bartons’ little house in a back courtyard. As John Barton stoked the fire, the light revealed a room furnished with a dresser, a cupboard displaying their few bits of china, and a deal table and chairs. Blue-and-white check curtains at the windows and a couple of straggling geranium plants on the windowsill added a cheerful touch, as did the green japanned tea tray propped up on the table next to a crimson tea caddy. A brightly coloured piece of oil cloth covered the floor between the coal hole and the fireplace.

George and Jane Wilson sat in the chairs on either side of the fire, distracting their young twins with bread and milk. They politely pretended not to notice the clinking of small change as Mrs Barton gave her daughter Mary some money and instructed her to run to the shop round the corner to fetch five eggs, some Cumberland ham, a pennyworth of milk and a fresh loaf of bread. Her father John added that she should stop at the Grapes public house for ‘six-pennyworth of rum to warm the tea’.1 On her way to the shop, Mary was instructed to call on Alice, George Wilson’s sister, who lived in a cellar round the corner, and invite her to come and join them. But she was not to forget to tell her to bring her own teacup, as the family only had five. By the time Alice had hobbled to the Bartons’ home, Mary had returned with her purchases and was busy frying the ham and eggs while her mother presided over the making of tea at the table. The two families ate in silence, for the poor believed in savouring their food rather than engaging in distracting chit-chat.2

The Bartons and the Wilsons were the invention of Elizabeth Gaskell, who begins her novel Mary Barton, published in 1848, with these scenes. Gaskell wrote the book in an attempt to elicit middle-class sympathy for the plight of the working classes. She introduces us to the characters at a prosperous moment, but the rest of the novel is set during the trade depression of the early 1840s, when the northern mill workers were reduced to hunger and want. In the early nineteenth century, Britain’s industrial towns tripled in size within a few decades, swelling into cities as hundreds of thousands migrated from the countryside in search of work.3 While some, like the Harding and Pinfold families (whom we met in Chapter Twelve), exchanged their damp, run-down cottages for colonial cabins, the majority moved into the urban slums. Here the air reeked of coal smoke, and the houses, thrown up by unscrupulous speculative builders, were crowded together around inner courts where wet washing flapped damply above pools of filthy water contaminated with undrained sewage.4 Nevertheless, the new arrivals hoped to improve their lives, for while a rural labourer might scrape along on a weekly wage of as little as 8s., a skilled storeman in Manchester could earn as much as £2 17s. and his family could eat meat and potatoes every day.5

Although urban wages were potentially higher, industrial workers led insecure lives. As the philanthropist Florence Bell observed, even the thriftiest working man with a decent job walked along the ‘margin of disaster’ at all times.6 The slightest sickness or disability, a downturn in work or some other ill fortune could plunge a relatively prosperous family into immediate poverty. And as nineteenth-century industry lurched through a series of depressions, tens of thousands of workers were intermittently thrown out of their jobs.7 The 1840s recession described in Mary Barton was one of the worst. More than half the workers were laid off in mill towns across northern England, and the unemployed were reduced to penury.8 Elizabeth Gaskell visited the families of the poor during that time and was haunted by the words of a man who grasped her arm tightly and asked, ‘Ay ma’am, but have ye ever seen a child clemmed [starved] to death?’9 Middle-class critics condemned the workers as improvident for failing to accumulate savings that could tide them over these difficult periods. But even the best industrial wages were never sufficient to allow workers to do more than live from hand to mouth: ‘consum[ing] today what they earned yesterday’.10 Charles Dickens condemned the manufacturers, who treated their workers like objects rather than people, ‘to be worked so much, and paid so much, and there ended; something to be infallibly settled by laws of supply and demand’.11

Like the rural labourers in the late eighteenth century, the industrial poor were reduced to eating shop-bought bread, sugar and tea. Those who could not afford to light a fire for the twenty minutes or more it took to boil potatoes had to eat a slice of wheat bread smeared with treacle. In Sheffield, where coal was relatively expensive, there were twice as many bakers as in Leeds, where coal was cheaper.12 The poorer the family, the more they spent on bread. Bread absorbed more than 30 per cent of the wages of a Manchester mechanic’s assistant, while the better-off storeman spent less than 20 per cent of his weekly wage on bread.13

The more bread the industrial workers ate, the more sweetened tea they drank. Friedrich Engels, who had turned his back on the ‘port wine and champagne’ lifestyle of his own mill-owning class in order to explore Manchester’s slums, noted that tea was ‘quite indispensable’ to the poor and was forgone only when the ‘bitterest poverty reigns’.14 This was not, as judgemental commentators claimed, because tea satisfied a debauched working-class craving for nervous stimulation, but because, as one more empathetic physician understood, it had a ‘reviving influence when the body was fatigued’.15 This was no wonder considering the amount of sugar a working-class cup of tea contained. A family of iron workers whose diet was investigated by Florence Bell dissolved 4 lb of sugar – enough to fill ten teacups – in their weekly ½ lb of tea.16 Dr Edward Smith, investigating the diets of mill workers caught up in the ‘cotton famine’ of 1861, found that even when they cut back on the amount of foodstuffs they bought, including bread, the amount of sugar they purchased remained the same. The only difference was that rather than buying it in the form of lumps to put in their tea, they purchased it as treacle to spread on their bread. This made economic sense, as a pennyworth of treacle will have given them around four times more energy than a pennyworth of margarine.17 Cotton workers in the 1860s ate as much as double the amount of sugar as other workers: sugar really did fuel the Industrial Revolution.18

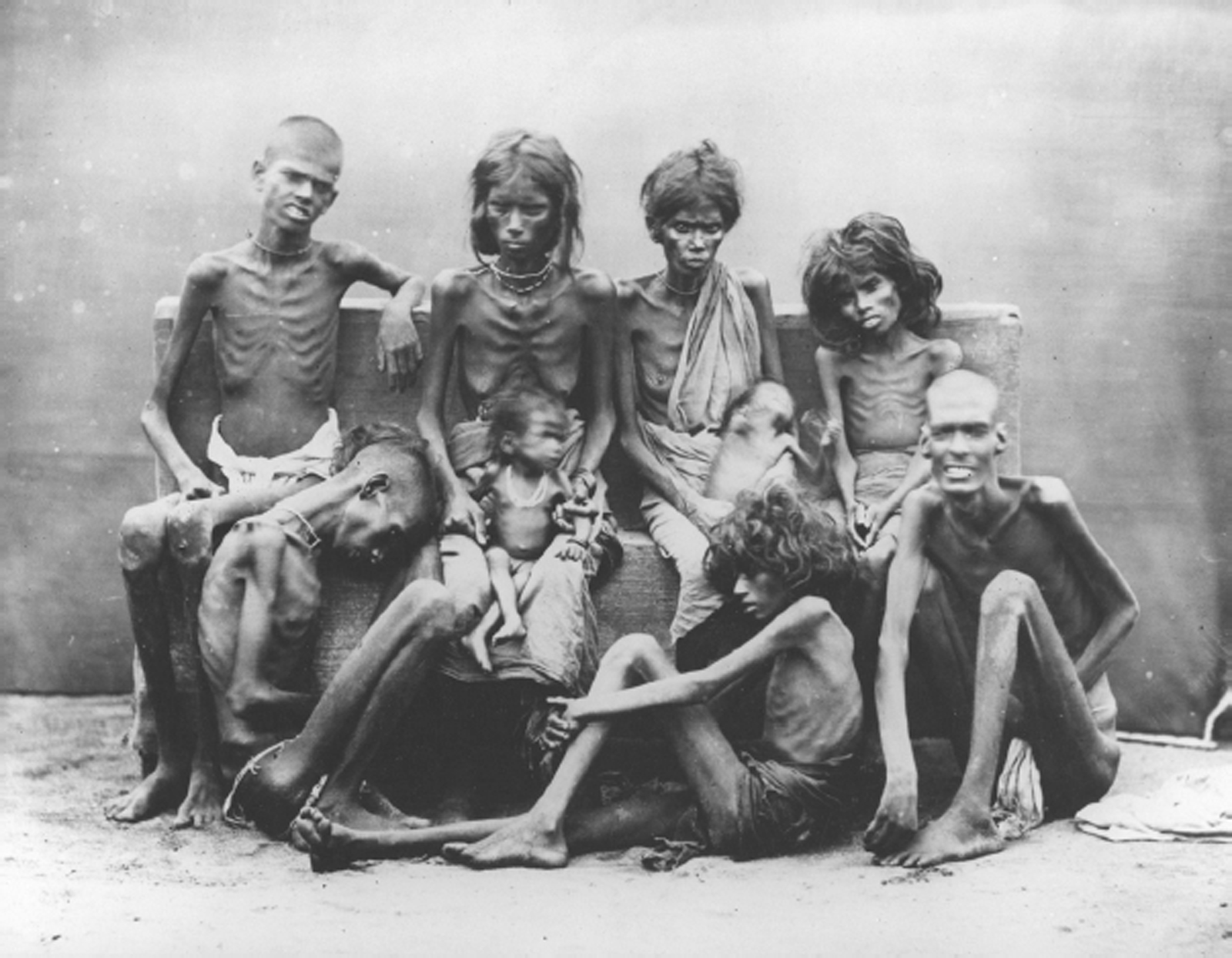

Children brought up on this impoverished diet were malnourished, and in the insanitary conditions of the industrial conurbations they fell victim to pneumonia and tuberculosis, diarrhoea and rheumatic fever. Those that survived childhood were severely stunted, as their bodies had diverted what nutrients could be gleaned from their food into recovery rather than growth.19 Working-class adolescent boys from the industrial cities were on average a staggering 10 inches shorter than those from privileged backgrounds.20 The grinding poverty and squalor reduced life expectancy in Manchester to just 26, a full 10 years less than the national average.21 Elizabeth Gaskell was at her best in her novel when she allowed John Barton to express the injustice of the system: ‘If I am out of work for weeks in the bad times, and winter comes, with black frost, and keen east wind … does the rich man share his plenty with me, as he ought to do, if his religion wasn’t a humbug? … don’t think to come over me with th’ old tale, that the rich know nothing of the trials of the poor; I say, if they don’t know, they ought to know. We’re their slaves as long as we can work; we pile up their fortunes with the sweat of our brows.’22 It was clear that something needed to be done about the plight of the workers. Dissatisfaction was fuelling demands for political change. In her novel, Gaskell has John Barton travel to London with the Chartists, who in 1842 handed in a petition of 3.5 million signatures to Parliament calling for manhood suffrage. Friedrich Engels was convinced that if the middle classes continued to ignore the poverty and distress of the workers, they would surely rise up in revolution as they had done in France in 1789.23

The Anti-Corn Law League argued that the solution would be to repeal the Corn Laws. These had been introduced in 1815 and were designed to favour British farmers by effectively preventing imports of cheaper Russian and American wheat from entering the British market.24 The founders of the League, Richard Cobden and John Bright, insisted that if cheap wheat imports were allowed, this would force down British wheat prices and consequently bring down the price of bread, freeing the working man from the tyranny of hunger. Many industrialists supported the League for the cynical reason that if the price of bread were to fall, it would allow them to keep wages low. Of course, the aristocracy, who derived their income from the land, were opposed, as decreasing wheat prices were likely to push down farm rents. However, although the aristocracy dominated Sir Robert Peel’s Tory government, the prime minister himself was in favour of opening up the British domestic market to free trade. Apart from anything else, it was difficult for the government to justify effectively barring cheap American grain imports when due to the failure of the potato crop in Ireland, the Irish were ‘reduced to the last extremity for want of food’.25 Peel was convinced that imports of cheap ‘Indian cornmeal’ (maize) from America would minimise the need for expensive relief efforts.26 By a series of complicated political manoeuvres, he managed to defeat the two thirds of his own party members who opposed him.27 In 1846, the Corn Laws were repealed and the British wheat market was opened up to foreign competition.

The triumph of the doctrine of free trade created the conditions for the emergence of a new imperial food regime. Until now, the colonies had supplied the mother country with useful raw materials and tropical agricultural goods such as sugar that could not be cultivated in Britain’s temperate climate. But those European migrants who had chosen colonial farms over urban slums had extended Britain’s agricultural estate into parts of the world suited to the cultivation of temperate crops. On these distant fields it was possible to grow more than enough to provide Britain’s ever-increasing workforce with enough cheap food to distract them from all thought of revolution. In effect, Britain had exported not just its farming population but almost its entire agricultural sector to the United States and the new settler colonies. From the mid nineteenth century, the country looked to its trading empire to supply it with staple foodstuffs.

During the parliamentary debate on the repeal of the Corn Laws, the Tory landed interest warned that the foundations of British democracy would be undermined if British farmers lost their protection from foreign competition. And immediately after the repeal there was a flurry of panic among small farmers. A disproportionately large number of those emigrating to the United States in 1850 were tenants from counties such as Surrey and Lancashire where it was a struggle to grow wheat on undercapitalised farms with heavy clay soils. Rather than lose their livelihoods to the Americans, with their limitless access to ‘untaxed and fertile soil’, they went to join them.28

America’s family farms may have been anachronistic in their idealisation of the sturdy yeoman farmer, but they were progressive in their farming technique. The pioneers who ventured onto the prairies of northern Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa and eastern Minnesota used mechanical reapers, which substantially increased the amount a farmer working on his own could harvest.29 When, in the 1870s, they moved onto the great plains of Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas, they added the wire binder to their battery of machines, which doubled their productivity.30 But the mechanical innovation that assured American wheat’s competitiveness was the invention in 1848 of the steam-powered grain elevator. Elevators transformed wheat from a product that individual farmers transported in sacks, and that took days to load and unload on the backs of stevedores, into a quality-controlled bulk commodity. By means of a series of mechanised buckets, grain was scooped out of boats on the Illinois and Michigan canals and taken up to the top of the elevator to be weighed and graded. Using the force of gravity, the wheat was then channelled into appropriate storage bins from where it could be poured down a chute into a rail car or ship’s hold. In 1857, when all twelve of Chicago’s elevators were in operation, they could process half a million bushels of grain in ten hours at the cost of only half a cent a bushel.31 Low freight charges on the sailing ships that transported the wheat across the Atlantic meant that it cost less to ship grain from New York to Liverpool than it did to transport Irish wheat on the canals to Dublin and from there across the Irish Sea.32

From the mid 1860s, at times more than half the American wheat arriving in Britain was grown not in the Midwest but in California. The fact that wheat from the arid Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys could be transported in sailing ships 14,000 nautical miles down the west coast of South America, around Cape Horn and across the Atlantic and still compete with wheat grown in East Anglia was a triumph of organisation and efficiency.33 Using the most up-to-date farming methods, Californian farms produced far more wheat than the population of San Francisco and the gold-mining towns dotted around the state could possibly eat. When they went in search of a market, the Californians discovered that British and Irish millers were prepared to pay top prices for their hard, dry, unusually white wheat. But transporting it to the eastern seaboard on the new transcontinental rail lines was too expensive, and steam ships were out of the question, as the cost of the coal necessary to fuel the long and arduous route round Cape Horn was prohibitive.34 Isaac Friedlander, a German-Jewish immigrant who had moved to California from South Carolina during the 1849 gold rush, found the solution. He used the newly established transatlantic and transcontinental telegraph systems to co-ordinate the arrival of a flotilla of clipper ships in San Francisco harbour just as the wheat harvest was flooding onto the market. Clippers had been invented for the China trade in the 1840s after the East India Company had lost its monopoly. Narrow and yacht-like, they were designed to race cargoes of the new season’s tea back to Britain, where the first ships to arrive were able to capitalise on the highest prices. As the California wheat trade flourished, New England shipbuilders responded by producing bigger, stronger ships, thus reducing the four-to-five-month journey between San Francisco and Liverpool to 100 days.35

In 1882, when the Pacific wheat trade peaked, 550 ships sailed under the Golden Gate on their way to Liverpool, where Californian wheat dominated the market. On the Liverpool exchange, wheat was sold by the cental (100 lb) rather than the more usual bushel, as the Californian wheat was shipped in 100 lb sacks. Meanwhile, the trade meant that Britain dominated the American state. The clipper ships were almost all British-owned, and insured by British brokers; two of San Francisco’s leading banks were British; and it was British capital that funded the building of railways in the late 1860s that linked the wheat-growing valleys to the port. For the decades during which wheat was California’s leading export crop, the state was effectively a British colony.36

The San Francisco–Liverpool wheat run was, however, the last hurrah of the sailing ships. In 1863, the compound engine, developed in the textile mills, was applied to marine steam engines. This was quickly followed by the invention of triple and quadruple expansion engines. Within the decade, marine-engine fuel consumption was halved.37 Steamships could now make much longer sea journeys, and larger steamships created economies of scale that caused freight prices to plummet throughout the last quarter of the century. In 1902, the freight rate for a quarter of wheat from New York to Liverpool was a mere 11½d, down from 5s. 2d in 1872.38 It was the drop in freight prices that brought about the collapse of British wheat farming. By embarking on a concerted campaign of drainage, manuring and investment in machinery, British farmers had managed to maintain a respectable share of the market: in 1870, they still supplied half the wheat in a loaf.39 But as freight prices dropped and American exports increased from 5 million hectolitres of wheat in the 1840s to 100 million hectolitres in the 1870s, British wheat farming went into steep decline.40

The landed interest had been correct when they argued that the repeal of the Corn Laws would adversely affect them. Once the fall in transport costs allowed foodstuffs to flow into Britain from around the world, the landlords’ rental incomes fell dramatically.41 In 1897, Herbrand, the 11th Duke of Bedford, published A Great Agricultural Estate, a polemic in which he alleged that the repeal of the Corn Laws had brought about the ruin of the landed aristocracy. He detailed how his estates of Thorney and Woburn were now running at a deficit due to falls in rents between 45 and 22 per cent. As George Russell, a radical Liberal and distant relative of the Duke of Bedford, pointed out, the aristocrat failed to mention that his estate in the West Country was financially buoyant and his urban landholding between the Strand and Euston Road brought in a substantial rental income. Indeed, when Bedford wrote his tale of landed woe, he was a very wealthy man, with an annual income of £319,369.42 While aristocrats did begin to sell their estates, it would take more than a decline in land value to undermine the patrician elite. The shrewd among them diversified their portfolios and invested in urban land, American railways, government bonds, mortgage companies and breweries, joining the gentlemanly capitalists of the City.43

By the 1880s, there was growing disenchantment on both sides with the mutual dependence of the British and American wheat markets.44 The Americans sought to escape Liverpool’s dominance by opening up new markets, while the British, having favoured dependence on America over Russia, now preferred the idea of relying on the Empire. In the 1880s and 1890s, measures were taken to stimulate wheat exports from India, Australia, Canada and Argentina. British investment in schemes to construct railways in these countries was frequently promoted on the grounds that this would allow them to replace the United States as Britain’s wheat supplier.45 In the 1880s, an enthusiastic group of private investors even suggested introducing into India an American-style wheat grading system, and grain elevators along the railways, in order to facilitate the export of wheat from the colony.46

When India became a Crown colony in 1858, internal commerce was facilitated by the unification of most of the subcontinent under one administration, using a single currency. Farmers were able to move their surplus rice and wheat crops to market more easily as bullock carts began replacing pack animals, roads were metalled and steamboats were introduced on the Ganges. Between 1850 and 1870, the British built an extensive rail network linking the twenty major cities. All this inexorably drew the Indian peasant into the market.47 There was a scramble to bring agriculturally marginal land into production, and farmers were encouraged to replace hardy subsistence crops such as millet with wheat.48 By the 1870s, district officers noted that the peasantry had given up storing surplus foodstuffs and instead sold their entire harvest. But this left them vulnerable at times of food scarcity and dependent on charity or government relief in the event of famine.49 And with the regular failure of the south-west monsoon, famines were a frequent occurrence.

As many as 16 million Indians died in famines between 1875 and 1914.50 The colonial government did very little to alleviate the misery, insisting that this was nature’s way of keeping a check on the burgeoning Indian population.51 But famines were not a natural consequence of poor harvests. They were the result of the unchecked functioning of the free market, which allowed merchants to continue to sell their wheat to the highest international bidders while inflation priced the poor out of their ability to buy food. Some administrators argued that famines were good for India’s agricultural sector, as they forced unproductive and indebted smallholders off the land.52 In fact, every famine had the effect of pauperising an ever greater proportion of the Indian population. And yet in 1900, one fifth of Britain’s wheat imports came from India.53

While Britain’s preference for empire wheat had a destabilising effect on Indian agriculture, it was a boon for Australian farmers looking for a way out of the economic slump of the 1890s. Farmers ploughed up their sheep runs and planted them with wheat varieties bred to suit the Antipodean climate. From exports of only a couple of hundred thousand tons in the early 1890s, Australia was exporting about two million tons by 1919, three quarters of it to Britain.54 At the same time, in Latin America, millions of southern European migrants spread out over the Argentinian pampas as the last of the Amerindians were driven off their lands. Although they practised a poor sort of extensive agriculture, with low yields, grain exports from their farms supported the national economy, earning most of Argentina’s foreign exchange.55 The country was drawn into Britain’s informal empire as its infrastructure of railways and ports was funded by British banks, investors and companies, and the Argentinian wheat trade became bound up with coal exports from South Wales.56 Welsh coal was used by navies and steamship companies throughout the world as it was slow-burning and did not reach damagingly high temperatures, making it the optimum fuel for marine engines. Grain ships sailing out to Argentina, which would have been more or less empty otherwise, took out cargoes of Welsh coal, which helped reduce the return freight rates for wheat.57 There had been expectations of Canada feeding Britain as early as the 1870s, when Canadian prime minister John A. Macdonald passed the Homestead Act and British investors sank millions of pounds into financing the building of the Canadian Pacific transcontinental railway. But it was not until freight rates were reduced in 1896 that it became economically viable for settlers to grow wheat for sale to Britain. Over a million farmers now drove the Métis and Plains Indians into reservations as they brought 9.2 million hectares under cultivation. By 1910, Canada had become the world’s leading wheat exporter.58

By the end of the nineteenth century, Britain absorbed between 30 and 40 per cent of the world’s wheat exports. Agriculture’s relative importance to the country’s economy declined dramatically, from contributing a third of the national income at the beginning of the nineteenth century to about 7 per cent at the end.59

The repeal of the Corn Laws and the influx of American wheat imports brought down the price of bread. In 1880, a 4 lb loaf cost as little as 6d, half what it had cost in 1840.60 The money this saved working-class families meant they were able to add a bit of bacon to their bread and butter at breakfast, some sausages or a piece of liver to their midday meal of potatoes.61 British dairy farmers took advantage of the nation’s new rail network to supply the towns with fresh milk, and working-class people were now able to enjoy the occasional glass.62 Two thirds of Britain’s wheat acreage disappeared as a result of cheap imports, and in Cambridgeshire, farmers switched to market gardening; fields of corn were replaced by orchards and rows of soft fruit.63 The further extension of the free market with the abolition of duties on sugar in 1874 was followed by a flood of unprecedentedly cheap German beet sugar in the 1880s, and this made it economically viable to convert the less-than-perfect strawberries, raspberries, damsons and plums into affordable jams.64 ‘Strawberry flavour’ at twopence halfpenny a pound became such a ubiquitous spread that whereas a middle-class child in the nursery looked forward to the treat of bread and jam for tea, ‘when given the opportunity at a party or a picnic, [the working-class child] will devote his attention to the luxury of bread-and-butter’.65 By the end of the century, sugar accounted for as much as 15 per cent of a worker’s daily intake of energy.66

The repeal of the Corn Laws and the supply of foreign wheat enabled Britain to feed its mushrooming industrial population; it may even have diverted them from social revolution, although it could be argued that the workers were simply drugged into compliance by lavish quantities of sugar. By 1880, their living standards had improved. Those earning the highest wages were able to spare a little for boots, clothing, bedding and cooking utensils.67 In most of Britain’s larger cities, life expectancy was now only a few years below the national average – although in Manchester it remained stubbornly at 37, ten years lower than the average.68 Yet overcrowding and insanitary conditions, irregular employment and poverty still afflicted about a quarter of the working population. Although the poorest no longer starved, their diet could hardly be described as healthy. Free trade did not bring about a marked improvement in the working-class diet until the Empire began sending Britain cargoes of meat as well as wheat.