Some of the biggest and most common obstacles to managing time efficiently are procrastination (putting things off, and perhaps never doing them at all), perfectionism, fear of failure, fear of success, and workaholism. These obstacles all have one thing in common – they originate in our thoughts, beliefs, and our self-concept.

In this chapter you will explore how to stop the cycle of procrastination and how to break the drive for perfection, which holds you back from accomplishing new things. You can also take a quiz to find out if you are working too hard. You will be given all the tools you need to change your negative thinking and to discover what is holding you back from becoming an expert time manager.

It is 3am and Janet is sitting at her desk, staring in to space. She is feeling very anxious because she needs to come up with some clever and innovative ideas for the company’s latest sales drive, and she has to present them to her boss tomorrow morning. She knew three weeks ago that the deadline was tomorrow, yet she didn’t start working on the project until yesterday. Was she too busy? Perhaps the task was too difficult for her or she wasn’t briefed properly? None of the above: Janet is struggling with procrastination, and it’s causing her a great deal of stress.

Procrastination – from the Latin pro cras meaning “for tomorrow” – means to defer a task until the last moment, or even to fail to do it at all. At a simple level, procrastination can result in missed deadlines, but it can also leave us feeling guilty, inadequate, self-loathing, and even depressed.

If people feel so bad because they leave things to the last minute, why do they do it? Here are some of the reasons why we procrastinate.

Fear of failure (see pp.38–40) “I just know I can’t do a good job of this. Better not to do it at all than to show them that I can’t do it.”

Fear of success (see pp.41–3) “If I make a good job of this project, they’ll continue to expect more and more from me.” Or, “I don’t deserve praise – recognition makes me feel uncomfortable.”

Negative self-beliefs If you tell yourself over and over again “I’m not good at this,” you will put off the anxiety-producing task.

Being too busy “I am much too busy to get anything else done.”

Being disorganized “I need to get myself organized before I can write that report.”

Between tasks we start the procrastination cycle by thinking “Next time, I‘ll start earlier.” Then, when we have our next task, we think “I’ll start soon.” Anxiety builds as we begin an internal chain of thoughts along the lines of:

• What will happen if I don’t start?

• I’m doing everything except what I should be doing.

• I can’t enjoy doing anything else while this is waiting to be done.

• Why didn’t I start sooner?

• What if someone finds out that I’m in this mess?

But the procrastinator thinks, “There’s still time for me to get it done.” However, then self-criticism often sets in and they lose confidence, asking “Do I get the job done or do I abandon ship?” Having failed to complete the task and feeling very negative, the procrastinator vows never to put things off again. But after the memory of the anxiety has faded, the cycle begins again.

Poor planning and time management “I should not have spent so much time with my friends at the weekend when I knew that I had this job to do.”

Getting easily frustrated “I just can’t stand it when I try to work and it doesn’t go smoothly or easily. I quit.”

Depression “There’s no point even trying to do this. What’s the use?”

Reflect on the price you are paying for procrastinating: anxiety, depression, and stress. Also, be realistic about what it has cost you in grades, employment opportunities, or career advancement, and the toll it has taken on your relationships. Now resolve to do something about it. The earlier in the cycle you can stop yourself, the easier it will be to get back on track. Then, break down the task into small, manageable steps. Write a schedule, setting a date by which each step will be completed. Now comes the crunch – getting started. This is often the biggest hurdle, but start you must. After you complete a step, give yourself a little reward. Then, following your schedule, start on the next one. As you complete each step you will gain in confidence, and before you know it, you will have reached the end of the project. Congratulate yourself!

If you are currently delaying doing something that you know needs to get done, here is a way to talk yourself into meeting that important deadline.

1. Write down the task that you are avoiding. “Study more” is too vague; something more specific, such as “Write essay on Shakespeare’s sonnets,” is much better.

2. Ask yourself why you are avoiding it. Don’t you like the task? Are you afraid that you can’t do it well? Do you feel you are too disorganized? If you are having difficulty discovering why you procrastinate, ask a friend or colleague the reasons why they might put things off.

3. List reasons why delaying might benefit you. For example, you can do other things that you prefer instead; you don’t actually have to get down to work; you don’t have to face anxieties about the task; and so on.

4. List reasons why delaying might hurt you. For example, you won’t get a good exam grade; or your children will be too embarrassed to have their friends over if you continue to avoid cleaning the house.

5. Think positively about yourself and the task before you. Break the task down into smaller, more manageable chunks, and set yourself mini-deadlines by which you need to have completed each part of the task. Aim for completion, not perfection.

6. Ask a friend or colleague to help you by making you accountable to them. Tell them the date by which the task has to be completed and get them to check on your progress from time to time.

When we have a task to do, most of us strive to do a good job. However, for some people, this is not enough – they want to do a perfect job. Perfectionists live in a world of self-imposed, unrealistic standards and expectations that cause them to strive continually for the unobtainable. They don’t tolerate mistakes and they become bogged down in the smallest details, often starting over again and again in a bid to get the job done absolutely right.

In time management, perfectionism and procrastination are two sides of the same coin because both prevent us from using our time wisely and completing the task. A perfectionist seldom accomplishes anything that is acceptable the first time around. They may delay starting a task because they know that it will take a huge amount of energy and they will become frustrated, angry, and anxious as time passes.

Perfectionism often starts in childhood as a desire to please others. Gifted children can struggle with the high standards imposed by adults and take on these standards as their own. They may mistakenly internalize the message that their value is equal to their performance. The child wants to please their parents and teachers, and over time their desire to please others turns into a fear of rejection. Often motivated more by fear than the desire to succeed, the perfectionist may avoid new situations or refuse a job promotion because they are afraid that they cannot perform to their own high standards.

The perfectionist lives by the rule of the “shoulds”: I should be perfect and everything I do should be perfect; I shouldn’t make mistakes; I should always give 150 per cent regardless of the circumstances; I shouldn’t attempt to do things if I know ahead of time that they won’t be perfect.

Being a perfectionist can be a lonely experience. Low self-esteem and lack of confidence are obstacles that perfectionists struggle with. Unwilling to try new things for fear that they can’t do them well, the perfectionist may become stuck in rigid thinking about what they can and cannot do. Perfectionists are at risk of pessimistic thinking and depression. All-or-nothing thinking is a forerunner to pessimism and depression in the perfectionist’s world. Anything less than 100 per cent success is a total failure. “If I can’t do it perfectly, I won’t do it at all.”

Accept that making mistakes is a human trait. You will learn more about yourself through failure than success, but nothing is a complete failure if you’ve learned something.

Strive for excellence instead of perfection. Block out the time required, do the preparation, get the job done in the time allotted, and feel good about it. Use the Pareto Principle (see pp.26–7) to help you learn where to put your time and energy. In this case 20 per cent of your effort produces 80 per cent of the quality. Doing an adequate or satisfactory job (the 80 per cent) is much better than getting nothing done at all.

Learn to differentiate between doing something right and doing the right thing by asking yourself if the details that you are fussing over are important to the overall project. Give yourself a reasonable schedule and stick to it. Use a small alarm clock or timer to remind you when the time is up. Then force yourself to move on to the next task. Factor in time at the end to review and tweak, but set a time limit on that as well.

Be patient with yourself as you practice being imperfect. Perfectionism is a trap that is worth escaping – when you do, you will like yourself more, enjoy the process of doing things rather than focus solely on the result, expand your repertoire of skills, and, most importantly, you will be able to let go of the stress and anxiety that are intrinsic to being a perfectionist.

What would you do if you knew that you didn’t have to do it perfectly? This exercise helps you discover what you have always wanted to try but were afraid to, because your inner perfectionist is holding you back.

1. Assemble the following: a collection of different types of magazines (lifestyle, travel, business, gardening, and so on), a large sheet of art paper, a pair of scissors, and some glue.

2. Block off one hour of time, play some of your favourite music, light a scented candle, and take a moment to relax. Flip through the magazines, one page at a time, and continually ask yourself the question, “What would I like to do if I knew I didn’t have to do it perfectly?”

3. Follow your impulse and tear out any pictures that represent something you‘d like to try but haven’t because of your need to be perfect in all things. Don’t censor yourself or question your abilities. Just follow your intuition.

4. After about 30 minutes, use the scissors to trim the images and paste them onto the art paper to create a collage.

5. Reserve the last 15 minutes to think about which activity you would like to try most. How would you begin? For example, say you’d like to make over your garden but have been intimidated by your own high standards and the size of the task. You might start by planting a small window box. Whatever you choose, the pressure is off when you no longer need to be perfect.

No one likes to fail at anything and a fear of failure is one of the most common anxieties we face. Everyone has doubts about their abilities from time to time, which can cause them to hesitate to try something new or something they know they are not particularly good at. A fear of failure is linked with a fear of being criticized or rejected, but not all fears are bad – our innate survival instinct, which is based on fear, protects us from harm and warns us of danger. However, fear becomes a problem when it limits our capabilities and diminishes our quality of life.

The fear of failure can spiral into a vicious cycle. The anticipation of the worst-case scenario leaves you feeling anxious and stressed. You withdraw from the task at hand and/or from others because you feel embarrassed and don’t want to ask for help. You abandon what you are doing, or keep putting it off, or perhaps you never even start. Your self-confidence plummets and you generally feel bad about yourself, thinking, “I’m a loser, I can’t do anything.” You feel like a failure in all areas of life; your anxiety increases.

Yet people who accomplish their goals know that failure is a natural by-product of trying. If you don’t try, you will certainly never fail – but you won’t succeed either.

Ask yourself what exactly you are afraid of. Being judged? Looking silly? The possibility that friends or colleagues won’t like you? Is there any evidence to support these fears? What’s the worst that can happen if someone judges you? Often, once we have accepted what the worst outcome could be, our fears lessen and we feel more positive about trying.

Try not to let your emotions control what you are going to do and when you are going to do it. Take action first and the good feelings will follow. Similarly, don’t wait until you get in the right mood before starting; instead, just get going – your mood will improve because you are doing something and you will feel better about yourself because you are trying.

What may be done at any time will be done at no time.

SCOTTISH PROVERB

Avoid undermining yourself and asking yourself “what if” questions, such as: “What if I can’t do it well?” and “What if I fail?” This will only drain your confidence. Focus on your effort – that is the most important part – and congratulate yourself for trying.

Develop persistence. Follow the advice of the American humorist Josh Billings (1818–85): “Be like a postage stamp – stick to one thing until you get there.” Keep trying and when you get anxious or frustrated give yourself ten more minutes to work on the task and then take a short break. Then, return to work with renewed determination to see the task through.

Inevitably, everyone experiences failure at some time or another, and when you do you will realize that missing a deadline or not managing to complete a task is not as terrible as you had thought – it doesn’t mean you lack character and it doesn’t reflect on your value as a person. Instead of chastising yourself, try to use the experience as an opportunity to grow and develop.

It can also help to review a situation where you failed to complete something because you were afraid of failing. Identify where you got stuck. Was it before you started the task, after you started it, or toward the end? Why do you think you stopped when you did? Were you unprepared to do a certain aspect of the task? Did it take longer than you thought and you panicked at the idea of running out of time? And so on. Once you have some answers, you can approach your next task differently so that the fear of failure does not prevent you from completing the job.

Finally, watch your thoughts. Be aware of your internal dialogue when things go wrong. “It didn’t work out” is quite different from saying “I am a failure.” Changing your perspective and reframing the failure as a temporary setback will allow you to learn from the experience and move on.

While the fear of failure is the fear of making mistakes and looking foolish, the fear of success is the fear of achievement and the recognition that success brings. People who struggle with the fear of success often do not understand why they have problems making decisions, lack motivation to achieve their goals, and are chronic underachievers. If they do complete something successfully, they denigrate their achievements, put themselves down, and say that it was just a stroke of luck.

Those who fear success are masters of self-sabotage. They set things up to fail: They hand in the report late or incomplete, or they don’t turn up for their creative writing workshop even though their work is highly regarded by the teacher. But why? Perhaps being successful does not fit with their self-concept. They view themselves as undeserving of success.

How can the fear of success sabotage effective time management? Self-sabotaging your time-management efforts can occur in subtle ways: not preparing a schedule when you know that this is the best way for you to operate; not using your calendar even though you carry it around with you; letting people interrupt you and take up your valuable time when you are trying to finish a project; or waiting until the end of the day when your energy is low to work on important projects.

It’s a good idea to analyze what would be different in your life if you stopped sabotaging yourself and became successful. What are the pros and cons of success? There must be some benefits from self-sabotage or you wouldn’t be doing it. Perhaps you don’t want to deal with the consequences – such as promotion or moving house – that success might bring? Once you pinpoint why you are sabotaging yourself, you can start to address the problem.

Another way to push past your fears to success is to define your goals, both long- and short-term. While the fear of success is in the present, your goals are future-oriented. Use them to remind yourself why you need to overcome your fears.

A little positive brainwashing can also go a long way to helping you overcome a fear of success. Repeat to yourself, “I deserve to be successful,” at least ten times a day. Also, write out this positive affirmation on small, adhesive notes and put them in places where you often see them, such as on your bedroom mirror, on your computer monitor, on the dashboard of your car, and so on.

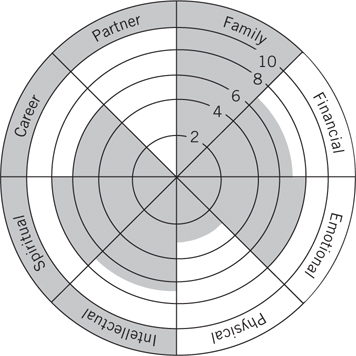

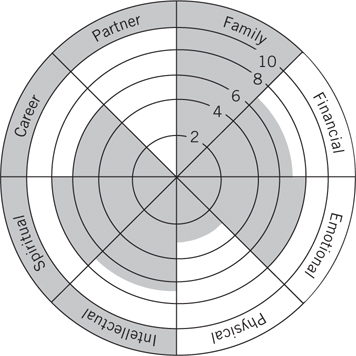

How will you know when you are successful? What does being successful mean? This exercise will help you to discover your own, personal definition. You will need a paper plate or a sheet of paper with a circle drawn on it, and a pen.

1. Divide the paper plate or circle into segments representing the areas of life that are important to you (see diagram below). Label each segment and mark on the numbers as shown. Now indicate your satisfaction with each area of your life on a scale from 0 to 10 (where 0 = not satisfied at all and 10 = completely satisfied). Draw a line across each segment at the appropriate point and shade in the area produced.

2. Join up the points on the segment lines. Chances are, you are closer to your definition of success in some areas than others. Reflect on how you have achieved success in these areas.

3. In the segments where you rated your level of success as low, answer the question: “How will I know when I have achieved success in this area?” For example, in Physical, your answer might be: “When I can run a half marathon.”

4. Schedule time in the areas you need to improve to make your answers a reality.

Being a workaholic is a socially acceptable addiction – no one looks down on hard workers: We encourage and reward them. There is nothing wrong with loving your work, feeling satisfied when you have put in a long day, and going the extra mile to make sure a project is completed on time. The difference between a hard worker and a workaholic is control. The hard worker is in control of when and how hard they work, and there is a balance between work and the rest of their lives. The workaholic, on the other hand, feels anxious when not working, finds it almost impossible to relax, and sometimes resents time spent with family and friends. The key indicator that a person is out of control and a workaholic is the bad state of their personal relationships. Spouses and children often suffer most because their husband/wife/father/mother is spending so little time at home. Workaholism can be an important factor in divorce, and children of a workaholic parent often complain about the lack of time spent together.

Workaholics can be found in virtually every profession and work setting: doctors, lawyers, carpenters, teachers, social workers, artists – no occupation is exempt. People in professions that use hourly billing, or work according to a corporate culture that rewards those who put in extra-long hours, or entrepreneurs and the self-employed are especially at risk.

Work addiction takes both a physical and a mental toll. Stress caused by burning the candle at both ends can result in many symptoms, such as: high blood pressure, anxiety, skin rashes, a depressed immune system, insomnia, bouts of anger, impatience, nausea, and back and joint pain. And if the workaholic does not slow down and learn to enjoy time away from work, he or she is at risk of burn-out.

Although burn-out is not recognized as a medical condition, it can be very debilitating. Burn-out related to work addiction is a type of depression that develops as a response to work-related stress – in this case caused by spending too much time at work. It develops over years and is characterized by physical exhaustion, sadness or depression, taking longer to complete work responsibilities, shame that you can’t work as hard as you used to, poor concentration, and an inability to make decisions. Many workaholics refuse to acknowledge what is happening until their symptoms are so severe that they are physically unable to address the problem. At that point, we need rest and recovery. Burn-out often forces us to re-assess who we are in relation to work, why we do a particular kind of work, and what needs to change so that we can find a better balance between work and the rest of our lives. Returning to work gradually, with a renewed sense of purpose and a more flexible attitude, will help us to become happier and healthier.

The road back from workaholism and burn-out can sometimes feel slow and painful, but it can be done. A good start is to let go of the guilt and anxiety of not working 24/7. Remind yourself that you are a better employer/colleague/entrepreneur/student if you take time to relax and revitalize yourself. You will be more efficient, creative, and productive.

Once back at work learn to delegate. Relieve yourself of some of your workload by delegating chores to a trusted employee. Practice trusting others to do the job as well as you would. If you don’t have an employee or you work at home, consider hiring someone to do the mundane tasks to free up some of your time. Or try trading tasks with a friend.

Make sure that you give the important people in your life a chunk of your prime time. Stop giving your family and friends the left-over time at the end of the day and at the weekends and spend some time with them when you are in top form. Perhaps you could schedule some fun time for a Saturday morning when you would normally go to work, or set up (and keep) a date night once a month with your partner or with friends.

Take time to take care of your physical health. Being in good physical shape has many well-known benefits, but for the workaholic there is an additional one: It requires taking time away from work. Schedule time to run, to go to the gym, or to use exercise equipment at home – whatever you can do to help you get, and stay, in shape. Exercise helps to manage anxiety and stress and produces mood-enhancing endorphins. Exercising with others, such as your children or friends, will give you the added bonus of re-building your relationships.

As you incorporate changes into your work routine and work less hours, be aware that you may experience withdrawal symptoms. You might find yourself feeling down, especially if you liked the adrenaline rush associated with a fast-paced, all-consuming work life. You might also feel agitated and impatient. These feelings are normal and common when lessening the grip of the amount of time and energy that your work consumes.

Time management is not a method for you to work harder and longer. Effective time management incorporates all of the areas of your life from work to family to leisure.

This exercise is adapted from How do I know if I am a workaholic?, published by Workaholics Anonymous.

Answer the following questions with a simple “true” or “false” response:

• I get more excited about my work than my family or anything else.

• I take work with me on vacation.

• Work is the activity I like to do best and talk about most.

• I work more than 55 hours per week.

• My family and/or friends do not expect me to be on time.

• I believe it is okay to work long hours if I love what I am doing.

• I get impatient with people who have other priorities beside work.

• I am afraid that if I don’t work extra hard I will lose my job or be a failure.

• I worry about the future even when things are going very well.

• I get irritated when people ask me to stop doing my work in order to do something else.

• My family complains about the amount of hours I work and that I am rarely home.

• I think about work most of the time: while driving, when falling asleep, when I wake up during the night, when others are talking to me.

• I work or read work-related material during meals.

The more “true” answers you have given, the closer you are to being a workaholic. An awareness that you might have a problem is the first step toward changing. If you feel that you might need professional help, contact an organization such as Workaholics Anonymous or seek advice from a mental health professional.

There are only 24 hours in a day and it is neither healthy nor desirable to spend more than one third of this time working. This exercise will teach you how to cut back on long working hours and regain a balance in your life.

1. First you need to find out exactly how you are spending your time, so get yourself a notebook and pen. For the next two weeks you are going to record everything you do. Each evening write down what you did that day and how long each thing took. List everything, including everyday activities such as sleeping, eating, and washing.

2. Analyze your time record, concentrating on the time you spent working over and above your required hours (in most jobs a maximum of eight hours per day). Look for ways gradually to reduce the extra hours.

3. Start by making small changes. (If you try to make too many changes too quickly they won’t last.) For example, try finishing work half an hour earlier each day until you leave at the designated time. Or, take 15 minutes every lunchtime to go for a walk.

4. Learn to say “no,” both to yourself and to others who make demands on your time. Don’t add anything to your schedule without removing something that requires the same amount of time and energy.

5. Find a mentor to support you in your quest to reach a better work– life balance, someone you can trust: your partner, a friend, or even a counselor. Set up a system whereby they can alert you, or you can go to them, if you veer off track.