It is love, and especially the first season of love, which inspires the song of these birds. The spring awakens in them the desire of love and the desire of song at once; the males are the most ardent and . . . if placed . . . where they are unable to satisfy their sexual desires, and so extinguish at the same time the love of song, will sing throughout the greater part of the year.

JOHANN BECHSTEIN, Natural History of Cage Birds (1795)

Since Aristotle’s time it has been known that singing is closely linked with reproduction: that only male birds sing and they do so to announce their occupation of a breeding territory. In Darwin’s theory of sexual selection birdsong was an expression of the competition between males for territory and the opportunity to breed. But, more contentiously, Darwin also suggested that song had evolved because females were charmed and attracted by it. The songs of male birds were shaped by female preferences, precisely because females chose to reproduce with particular singers. Darwin supported his view by quoting from the great German bird authority Johann Bechstein, who wrote, ‘female canaries always select the best singer, and that in a state of nature the female finch selects the male out of a hundred whose notes please her most’. But what constitutes the ‘best’ song? Darwin assumed that the melodic nature of song, its degree of elaboration and complexity were what counted, much as they do for human listeners. Indeed, I suspect that the reason we like birdsong is precisely because it lights up the same parts of our brain that music does. Obviously, among birds what females find attractive varies from species to species. In some cases it is the melodic quality of song itself, in others it is the size of the song repertoire, in others still it is the rate or volume at which songs are uttered that matters.1

Confirmation of Bechstein’s statement about female canaries preferring good songs was a long time coming. But in 1976, by means of some elegant experiments, Don Kroodsma at Rockefeller University New York showed how isolated female canaries built their nests more quickly and laid more eggs when listening to recordings of rich song repertoires than they did when listening to poor song repertoires.2 The degree of elaboration of a song repertoire was clearly one of the cues females used to assess males. It has since been discovered that many animals, including ourselves, also prefer musical tones with a certain order and rhythm, in much the same way that our brains seem to prefer symmetrical over asymmetrical patterns. Kroodsma’s experiments showed convincingly that females can and do discriminate between the vocal displays of different males, thus refuting the concerns of many of Darwin’s sexist critics that females did not have the cognitive ability to make informed choices about their partner.

When Darwin turned to discuss humans in his book The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, he started with a conundrum: ‘As neither the enjoyment nor the capacity of producing musical notes are faculties of the least use to man in reference to his daily habits of life, they must be ranked amongst the most mysterious with which he is endowed.’ But by referring to music as a mystery Darwin was being disingenuous. Just like other ‘faculties’ that appear to be of no use in daily life, music, he argues, is a sexually selected trait important in the acquisition of partners, exactly as it is in animals.

Darwin also noted that music predominantly arouses pleasant emotions, especially those associated with love, lust and triumph, rarely horror, rage or fear. The parallel with animals is clear: ‘All these facts with respect to music . . . become intelligible to a certain extent, if we may assume that musical tones and rhythm were used by our half-human ancestors, during the season of courtship, when animals of all kinds are excited not only by love, but by the strong passions of jealousy, rivalry and triumph.’ Music serves as a male sexual signal, exactly as song does for birds, with females preferring the best composer.

Darwin made his concept of sexual selection palatable and digestible for his readers with an analogy they could understand: artificial selection. Sexual selection was just like men choosing the most attractive pigeons or the largest cattle from which to breed. By doing so they perpetuated the desired traits. Female choice was therefore responsible for extreme male displays like the peacock’s tail, the bowerbird’s bower and the nightingale’s song.

As Darwin was keen to point out, a crucial difference between man’s artificial selection and sexual selection in nature was that sexual selection was usually kept in check by survival value. A peacock’s tail is two rather than three metres long because of natural selection. Peacocks with tails longer than two metres might be monumentally attractive but would be hopelessly vulnerable to predators. Two metres marks the point beyond which the disadvantages of a large tail outweigh – literally – any reproductive benefit: tail length has been kept in check by natural selection. Artificial selection, on the other hand, knows no such bounds and in principle it should be possible to breed peacocks with even longer tails. The Japanese have done just this with the domestic fowl and produced the Onagadori or Phoenix strain, whose tail feathers trail up to five metres. Think, too, of all those portraits of strangely shaped prize-winning cattle with huge haunches and tiny heads. Darwin wrote, ‘. . . an attempt was once made in Yorkshire to breed cattle with enormous buttocks [which were no doubt extremely attractive to farmers and butchers alike] but the cows perished so often in bringing forth their calves, that the attempt had to be given up.’ A similar problem occurred among the pigeons Darwin admired most, short-faced almond tumblers. This breed would not have survived in the wild, for their stubby beaks are too short for the young to break out of the egg unaided. German song canaries, including Karl Reich’s strain of canaries that sang like nightingales, were similarly a sexual disaster from the canary’s own standpoint. The problem, for the female canary, was that while the male had been artificially selected to display in a particular way, the female’s preference had been left untouched. A male canary singing a nightingale song was about as sexy to a female canary as a male gorilla is to a woman – King Kong notwithstanding.

The wild canary’s song, like that of other birds, is a product of sexual selection. In the past, male canaries that sang elaborate songs left more descendants because their song, as Bechstein noted, made them more attractive to females and thus gave them a competitive edge. On the face of it the creation of the roller canary looks like a man-made version of the female choice part of sexual selection: men chose which songs they preferred and allowed the best singers to breed. But this is an illusion. The features of canary songs that were attractive to men turn out to be decidedly unattractive to female canaries. The male canary’s song is like a strand of DNA, comprising a mixture of crucial coding regions, spacers (or non-coding regions) and junk. The breeders of roller canaries naively focused their selection on the ‘junk’ part of the canary’s song. The roller’s ‘rorororor’ song is junk because female canaries are not turned on by it as they are by the songs of any other type of canary. Tucked away in the complex array of sounds that make up the wild canary’s melodic and varied song are some very specific phrases or trills – equivalent to the crucial coding regions in a twist of DNA. It is these that really excite females, instantly inducing them to adopt a mating position. (The discovery of something similar among humans doesn’t bear thinking about.) If these phrases are cut and spliced from a tape recording and played to a female canary, they have an almost immediate sexual effect, even in the absence of a male bird. The songs of roller canaries, on the other hand, are utterly devoid of these sexy syllables – so not only have breeders exaggerated the unattractive part of the canary’s song, they have simultaneously eliminated the attractive bits.3

Birdsongs are generated in much the same way as blowing across a blade of grass held between your thumbs. Utilising the same principle Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles, used a silk ribbon stretched between two pieces of wood and a set of bellows to create a sensational speaking machine in the 1770s.4 Reed instruments like the clarinet also work by passing air over a membrane and causing it to vibrate. In birds the sound-producing membranes reside in a structure known as the syrinx, which lies in the upper breast where the windpipe divides in two to join the lungs. In humans these membranes, the vocal cords, are much closer to the mouth.

The grass-and-thumbs system for making noise is very crude, but if you’ve tried it you will know that you can easily modify the quality and volume of sound by altering the thickness of the grass membrane, by how tightly you hold the grass or by how hard you blow. Now imagine a similar system but with infinitely more control and you’ve got a bird’s syrinx. The extra control is provided by two things. First, the shape of the membranes, and hence the type of noise they create, is finely regulated by a series of muscles and soft bony rings on the outside of the syrinx. Second, instead of having just one vibrating membrane, like our blade of grass, birds have two, one on each side of the syrinx.

As part of his study of birdsong in the 1770s, Daines Barrington persuaded pioneer surgeon John Hunter to cut up a selection of songbirds for him in an effort to establish exactly how they made their various calls.5

I procured a cock nightingale, a cock and hen blackbird, a cock and hen rook, a cock linnet, and also a cock and hen chaffinch, which that very eminent anatomist, Mr Hunter, F.R.S. was so obliging as to dissect for me, and begged, that he would particularly attend to the state of the organs in the different birds, which might be supposed to contribute to singing. . . . Mr Hunter found the muscles of the larynx to be stronger in the Nightingale . . . and in all those instances where he dissected both cock and hen that the same muscles were stronger in the cock.

So the syrinx, it seems, is better developed in males than females, and in birds with more elaborate songs. Later researchers found that the variation in syrinx design among different species was so great that it could have been used to establish the evolutionary relationships between different birds. At the same time this variation in design has completely frustrated those trying to understand how the syrinx actually works. Researchers summed up the syrinx like this:6 It ‘should be a morphologist’s dream. It is relatively isolated, contains a variety of muscles, and is replete with levers and potential oscillators. Yet that dream has . . . proved to be a nightmare.’

Most of us, armed only with our more modest larynx, can readily make noises similar to many birds (and of course some birds, including the canary, can make noises like the human voice), but what requires immense skill and training is stringing these noises together to produce a ‘song’.

No one knows how the avian brain controls song, but we do know that across different bird species the quality of song varies with the size and complexity of both the syrinx and the brain. As birds begin to sing in spring, the part of their brain that controls and remembers song, the higher vocal centre, increases in volume (and decreases once the breeding season is over). The male canary’s higher vocal centre is larger than the female’s, which is not unexpected given that males sing and females do not. The same region of the brain is relatively larger in those species that utter more sophisticated songs. But females still need enough neural circuitry to make sense of the male’s song. We also know that female canaries have the potential to sing and, given a shot of testosterone, this is exactly what they do. Scurrilous traders in the past dosed female canaries with testosterone and passed them off as males because they were worth more. Remarkably, one of the things testosterone does to a female canary is to stimulate that region of the brain concerned with song to enlarge by growing new cells7– something that was once considered impossible.

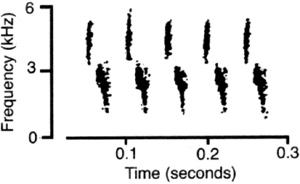

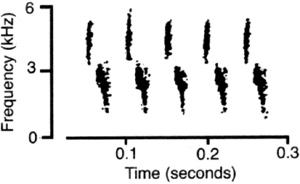

From a female canary’s point of view the key elements in a male’s song are those bits that tell her about his quality as an individual – the sexy syllables. If we look at a sonogram of these sexy syllables they look very special indeed. They are two-note trills repeated very rapidly – up to seventeen times a second – and rather like Tuvan throat singing (only better), or a musician playing an Etruscan flute or Picasso simultaneously painting a separate image with each hand. The canary’s two-voice syllables are made up of a low- and a high-frequency sound (Figure 2). Now recall the dual nature of the bird’s syrinx: the high-frequency sound comes from the right-hand side and the lower sound from the left. The simultaneous production of these sounds by the male canary requires extraordinarily sophisticated muscle coordination and it is precisely because these phrases are so difficult to produce that they accurately reveal a male’s quality. Only genuinely top performers can utter such intricate and intriguing sounds – they simply cannot be faked. This is the essence of a successful sexual display – it must honestly reflect a male’s quality. If all individuals could produce double-note trills they would be useless cues for females to distinguish great from mediocre performers.

FIGURE 2 A sonogram of the canary’s sexy syllables, here repeated just five times in a fraction of a second.

Karl Reich, of course, knew nothing of this research, which lay years in the future. He knew only that he succeeded where all before him failed. As they finished their cigars, Reich explained to Duncker that while others in the past had produced nightingale-canaries, he was the only person to breed an entire race of canaries whose exquisite song was so obviously inherited. The evidence, Reich said, was indisputable – his birds’ songs got better and better with each new generation and, what’s more, they continued to improve without hearing the merest strophe from a real nightingale. Impressed by what he had seen and heard, Duncker knew that Reich’s explanation, grounded as it was in a Lamarckian view of evolution, must be wrong.

Jean Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de Lamarck, as he was formally known, believed that useful changes acquired during an individual’s lifetime become incorporated into what we now call the genome and could be passed on to succeeding generations, a mechanism referred to as the ‘inheritance of acquired characteristics’. The giraffe was the perfect example, their long necks the result of generation after generation stretching up to pluck leaves at the tops of trees. Lamarck’s evolutionary mechanism was an optimistic one with deep intuitive appeal, for it seems only right that individuals should be rewarded for a lifetime of endeavour by having their efforts incorporated into their genetic heritage.

Breathless, Reich finished his soliloquy. His birds were his pride and joy, and his achievement had made him something of a celebrity across Europe. Outwardly enthusiastic and genuinely impressed by Reich’s birds, Duncker was privately sceptical that their song was genetically inherited. At the time, however, Duncker could not come up with a convincing explanation for Reich’s startling results.

Lamarckism was the most tenacious form of ‘soft inheritance’ and died only slowly. After the publication of the Origin of Species many people believed in evolution, but not everyone was convinced that Darwin’s notion of natural selection was the only mechanism by which species changed over time. There were two problems. Natural selection seemed sensible, but it lacked a coherent theory of inheritance and it was unclear whether it could ever be enough to bring about major changes such as the origin of new species. There was no doubt that a bird’s wing was a wonderful adaptation for flight, but many found it hard to see how it could have been created bit by bit by natural selection. What use would half a wing ever have been? For most people, including many biologists, natural selection on its own was not enough. Something extra was needed and the idea of ‘directed mutations’, that is, changes in tune with what an individual ‘wanted’, seemed to fit the bill. Evolution with a purpose was what many felt a benevolent God would have wanted. In other words, the hereditary process (whatever it was) produced adaptations automatically and allowed those characteristics acquired during an individual’s lifetime to be passed on to their offspring. The inheritance of acquired characteristics is now referred to as Lamarckism, even though Lamarck didn’t invent it (the idea went back to Plato), nor was it Lamarck’s main process of evolution. Nonetheless, the name stuck and Lamarckism was natural selection’s main opponent during Darwin’s time.

Later, in the 1880s, the brilliant German biologist August Weismann pointed out the utter fallacy of Lamarckism. His great insight was recognising that the germ plasm (the reproductive cells) was separate and distinct from the soma (the body) and nothing that happened to an individual’s body during its lifetime could be communicated to the reproductive cells. He was therefore one of the first to appreciate the difference between an animal’s appearance – its phenotype – and its genetic constitution – its genotype. Nonetheless, despite Weismann’s findings and Mendel’s convincing hereditary mechanism twenty years later, many biologists continued to believe in the inheritance of acquired characteristics. There was no rational scientific reason for this, they were simply reluctant to relinquish the comforting idea that evolution was progressive, just and driven by self-improvement. Not until about 1930 did Lamarckism finally start to fade away among mainstream biologists.

That Reich believed in a Lamarckian process of heredity was hardly surprising. He was a shopkeeper, not a scholar, and like many others before and since he was beguiled by the sense of natural justice inherent in a Lamarckian heredity. Almost all his bird-keeping friends believed in it and the newspapers in the 1920s were full of stories of some ingenious Lamarckian experiments conducted by the Viennese scientist Paul Kammerer.

Just before the First World War Kammerer claimed to have demonstrated the inheritance of acquired characteristics in several different animals – his best-known study being on the midwife toad. Most species of toads breed in water and to help them hang on to females the males develop a horny thumb pad. Because midwife toads breed on dry land, however, they have no need of thumb pads. What Kammerer did in his experiment was to force midwife toads to breed in water, and they developed thumb pads! Despite his apparent success, Kammerer’s experiments failed to attract the attention he felt they deserved. So after the war he reinvented himself and set off on a pro-Lamarckian publicity tour, denouncing followers of Gregor Mendel as ‘slaves to the past’ and touting Lamarckists like himself as ‘captains of the future’. He became a media star and persuaded Reich and many others to accept Lamarckian inheritance.

Kammerer remained in the spotlight only briefly. In 1926 the American scientist G. K. Noble asked to examine Kammerer’s voucher specimen – the single lecture-tour toad Kammerer had preserved for posterity – only to discover that the dark thumb pads were fakes created with injections of black ink. Devastated, Kammerer walked into the Alps and shot himself. Kammerer’s supporters proclaimed his innocence – someone else, possibly his assistant, had made the injections; a helping hand to generate the results Kammerer so desperately hoped for. The other rumour was that the Nazis had tampered with the toads to discredit the Jewish Kammerer because Lamarckism was antithetical to their beliefs.8

Reich’s beautiful songsters continued to tax Duncker, but he was absolutely convinced that the answer did not lie in Lamarckism. The puzzle forced Duncker to ponder how canaries and other small birds actually acquired their song. How much of it was genetic and how much was learned? For over two centuries there had been a tremendous incentive to answer this question – from a practical standpoint, if not a scientific one.

Hervieux’s handbook, published in 1705, provided clear and sensible instructions for training canaries to sing.9 He recognised that the young birds had what biologists and psychologists now call a ‘sensitive period’ in which they learned their song, and that to perfect their performance they must have no distractions at this critical time. Hervieux condemned the then common practice of putting young canaries in a dark box – from which few emerged alive – to help them learn: ‘If you desire to succeed better in that Point you must observe this Method.’ A few days after they are capable of feeding themselves, young birds should be placed individually in a cage covered by transparent linen in a room distant from all other birds whatsoever, so that he may never hear any of their Wild Notes, and then play to him upon a little Flageolet’ . . . After a fortnight the linen cover was to be replaced by one of ‘green or red Serge . . . till he perfectly learns what you teach him’. Hervieux recommended feeding the birds only at night by candlelight, the idea being that if kept without any visual distractions the young bird would learn more rapidly. ‘As for the Tunes, he must be taught only one fine Prelude and a choice Air; when they are taught more, they are apt to confound them.’ Hervieux urges patience – ‘for without it nothing can be done’ – and finally, ‘I have thought fit to prick down the Prelude and Air I have spoken of’ (see Figure 3).

Seventy years later Daines Barrington, in his ‘scientific’ study of birdsong, confirmed Hervieux’s assertions by rearing young linnets with different species as song tutors and showing that they learned only their tutor’s songs. He found that young birds continued to ‘record’, that is, learn their song, for ten or eleven months. ‘These facts . . . seem to prove very decisively, that birds have not any innate ideas of the notes which are supposed to be peculiar to each species.’10

But Barrington was not wholly correct. Research conducted in the 1950s – paradoxically much of it on chaffinches rather than canaries – revealed that most songbirds do have an inbuilt concept of what they should learn. When young chaffinches were hand-reared and brought up without ever hearing a chaffinch song, they spontaneously began to sing something that most birdwatchers would recognise as a chaffinch song, but by comparison with wild birds they uttered only a very simple tune.

Isolation became a central part of song-learning experiments. The birds used in these studies were called ‘Kaspar Hausers’, after a dumb and helpless teenage foundling discovered in Nuremberg market place in May 1828. Allegedly the illegitimate son of the Grand Duke Charles of Baden, Kaspar Hauser was kidnapped as a baby and reared in isolation by peasants. After being rescued and learning to speak, it transpired that he had been kept in a hole and fed by a man who, after teaching him to stand and walk, abandoned him in the market place.11

The chaffinch is slightly unusual compared with other finches because, as Pernau, Barrington and Hervieux knew, canaries could easily be persuaded to learn the song of another species, whereas a chaffinch could not. This does not mean that the canary lacks an innate song template, only that its template is more flexible than that of the chaffinch.

FIGURE 3 An air that might be taught to canaries, from Hervieux’s book (1705) on the canary.

Hervieux trained his canaries with a flageolet – a small flute made of ivory or wood – its pitch precisely suited to match the canary’s vocal range. The term ‘recorder’ seems to be intimately associated with the training of singing birds. We now think of the recorder as a child’s instrument, but to ‘record’ meant to ‘remember’ and the recorder’s original purpose was to help a canary or other songbird remember its tune. A small volume published in London in the early 1700s, The Bird Fancyer’s Delight, thought to have been written by the Staffordshire ornithologist John Hamersley,12 exploited the contemporary fashion for training songbirds. It contained instructions similar to Hervieux’s for the canary, and no less than forty-three different tunes: eleven each for the bullfinch and canary, six for the linnet and the rest for various others. Some of the tunes, such as Handel’s Rinaldo and ‘The Happy Clown’ from The Beggar’s Opera, were already popular, but many appear to have been especially written by the next-to-anonymous Mr Hill – a flageolet-playing friend of Samuel Pepys, who was himself a flageolet enthusiast.13

The tunes in the Bird Fancyer’s Delight are generally rather jolly and often incorporate trills and other birdlike sounds easily fingered on the flageolet. The number of tunes allotted to each species probably reflects the facility with which different birds responded. The bullfinch and the canary had most tunes and were certainly the most popular singing birds. The woodlark has four tunes, the skylark and starling three and the nightingale just two. The sparrow, throstle (song thrush) and India nightingale (possibly the mynah), were given just one each.

Charming as it is, Hamersley’s little book was probably little more than a scam. Two hundred and fifty years later, when song-learning had become an important topic of scientific research, experts questioned whether birds could really master the rather complicated tunes Hamersley set out for them. It seems that Hamersley’s book was aimed at two types of people – those interested in practising the flageolet but with no interest in birds and gullible bird keepers who were too inexperienced to know that the tunes were too difficult for their pets.14 Scam or not, the Bird Fancyer’s Delight stayed in print for over a hundred years and remains popular among recorder players today.

Teaching canaries and other birds to sing particular tunes grew so popular that it was perhaps inevitable that someone would eventually design a small machine to save them the effort of puffing on pipes or flageolets. The early eighteenth century was a period of great inventiveness in Europe: the flying shuttle, the seed drill and more efficient steam engines revolutionised weaving, agriculture and industry. In France around 1730 a Monsieur Bennard designed and constructed the first serinette – a miniature barrel organ, with bellows and ten tin pipes – which, at the turn of a handle, produced a high-pitched tune suitable for a small bird to learn. The serinette was the first way of recording music and for those who could afford one it must have been rather like today’s Macintosh iPod – the most up-to-date of musical gizmos and an important status symbol. George III, who loved gadgets, had one that played several different tunes, but to little effect for in a fit of rage he killed his birds when they failed to learn as quickly as he expected. Serinettes feature in several well-known contemporary works of art, including William Hogarth’s 1742 painting of the well-to-do Graham children in which the serinette is operated by the boy, but the ‘pupil’ – a goldfinch – looks more interested in avoiding the children’s cat than learning a tune. In Jean Baptiste Chardin’s La Serinette (1751) the artist’s second wife (acting as model) is seated in another opulent interior with the bird organ on her lap and a canary x goldfinch hybrid in a nearby cage.

Serinettes came in various models, generating sounds of different pitch, and you chose one appropriate for the bird you wanted to train. The commonest type was the canary serinette, but there were versions for the blackbird and bullfinch, and even one for the parrot. Despite their inventor’s ingenuity, it was the neural abilities of the birds themselves – at least under this form of tutorage – that provided the ultimate limit on what could be achieved. The way they sang often left much to be desired. J. S. Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emanuel once exhorted his pupils to ‘play from the soul, not like a trained bird!’.15 With these limitations it is surprising that the serinette fad lasted as long as it did. But as the serinette sank into obscurity in the mid-nineteenth century it was replaced by a new fashion: bullfinches trained to mimic a human whistle.

Daines Barrington deliberately excluded the bullfinch from his study because it couldn’t sing without ‘instruction’. Its natural song was considered about as musical as a squeaky wheelbarrow. Despite this lack of innate vocal talent, in captivity – as Hamersley makes clear – it had been known since the Middle Ages that a young bullfinch could learn ‘almost any tune that is taught by pipe or whistle if not too long’. In addition, the male bullfinch is among the most gorgeous of European birds, with a luscious pink breast, black cap and slate-grey back, making it instantly appealing despite its reputation for being somewhat delicate as a cage bird. It was easily procured and earned its German nickname ‘Gimpel’, or fool, because it responded so predictably to a decoy bird and was easy to capture. When kept as a pair, bullfinches show an endearing fondness for each other that reflects their lifelong pair bonds in the wild.16

Starting in about 1850, training bullfinches to whistle folk tunes became a specialist occupation, and an important source of income for farmers and craftsmen in the Vogelsberg area of Germany. Piping bullfinches became incredibly popular and large numbers of them were sold (expensively) not only in Germany but also in Holland and England. When Darwin went to London to visit the German bird artist Joseph Wolf in 1870, he was greeted by Wolf’s pet bullfinch which immediately started to search for crumbs in Darwin’s beard. Like other finches, young male bullfinches learn their natural song from their fathers. To produce a piping bullfinch the young birds were taken from the nest and reared in isolation. They saw only their keeper, who whistled two German folk tunes to them – in the same order and same key – several times each day for about five months. After this the young bullfinch retained these tunes for life – if it was a male. Unfortunately for the trainers, the sexes of young bullfinches are indistinguishable and about half their effort was wasted on females who very rarely learned to whistle. Even the males sometimes failed to learn the tunes.17

William Cowper’s poem ‘On the Death of Mrs Throckmorton’s Bullfinch’ (1788) paid tribute to the bird’s learning abilities:

And though by nature mute

Or only with a whistle blessed,

Well-taught he all the sounds expressed

Of flageolet or flute

That a bullfinch can be taught to whistle a German folk song and a canary trained to repeat the song of a nightingale might imply that a bird’s brain is little more than a biological tape recorder. But a remarkable study by the German biologist Jürgen Nicolai in the 1950s shows what extraordinarily sophisticated mental processes are involved in birds acquiring their song.

The bullfinch is an enigma. For a bird with no natural song to speak of, its ability to learn tunes is absolutely amazing.18 Fascinated by this paradox, Nicolai decided to explore the full extent of the piping bullfinch’s hidden talents, studying wild birds in a local cemetery and captive ones in his own home. As an old man, Nicolai told me how his studies started when he bought a tame bullfinch, which had been advertised in the local newspaper. He never looked back: fascinated by this bird’s ability to sing, Nicolai began a comprehensive study involving fifteen folk-song-singing male bullfinches and their male trainers.

The first thing he found was that the young birds are extraordinarily motivated to perfect their songs, repeating them again and again, and just like a child, starting again from the beginning whenever they make a mistake. Second, when Nicolai made tape recordings and sound spectrograms of bullfinches and their trainers, he found that the birds always transposed the tune to a higher pitch, from F to F#, for example, or from G to G#. Astonishingly, the birds also seemed to have an inherent appreciation of exactly how a tune should go and usually performed it better than their trainer. Even if the air flow of the whistling trainer was slightly irregular, the birds always uttered a smooth and completely uninterrupted sequence of notes. The birds also had an uncanny feel for their tunes. If the trainer whistled the next phrase of a tune ahead of the singing bird, the bird would stop, wait and then continue where the man left off, completing the tune. Bullfinches could also recognise tunes as separate musical entities. Nicolai’s inspection of the spectrograms showed that trainers generally separated two tunes by a short pause, but no longer than the pause between different phrases within a tune. Yet the birds always sang the two tunes separately.19

There’s a final twist to the bullfinch’s tale. What gives us a preconceived idea of what we are looking for when searching for a partner? Among birds the notion of what is attractive – or sexual imprinting, as it’s called – is put in place in the first few months after leaving the nest. Young bullfinches were traditionally taken before fledging and reared and trained by men, and as a result became sexually imprinted on men – meaning that as adults they directed their sexual approaches to men, assuming them to be what they should establish a long-term relationship with. Trainers sold their young birds at the end of their education when they were four or five months old. Within just a few days they had transferred their affection to their new male owner and soon greeted him exactly as they would a sexual partner, with an endearing display of fluffed body feathers and twisted tail, piping their learnt tunes. Women, however, were rejected and birds reacted to them as though they were a completely different species. A bullfinch ‘which a lady (north of the Tay), bought from a German bird-dealer, because of the excellence of its song, was no sooner in her possession, than it became entirely mute, and, though apparently in perfect health, neither voice nor instrument could induce it to sing’.20 One wonders how many other disappointed lady customers the German dealers left in their wake.

Bullfinches can clearly distinguish between their male and female owners but these observations do not mean that they possess any innate preference for men over women. I suspect that had young bullfinches been trained by women, they would have been sexually imprinted on them as adults. The experiment, however, has never been done and may never be done. The tradition of training bullfinches died out in the 1970s, when the last trainers passed away.

For German song canaries, including Reich’s birds, singing is a product of both the right genes and the appropriate learning opportunities. But these qualities alone are insufficient to produce a champion. A third component is needed – one that Reich, like all Harzer breeders, knew all about. Young roller canaries require very careful management if they are to sing properly. The trick is to train them to sing in response to light and this is why competition birds are kept in small wooden cages with a pair of doors that open over the wire front. The birds learn to find their food and water in the dark, and the doors are opened for just ten minutes in the morning, thirty minutes around midday and another ten minutes in the evening. In this way, as Reich demonstrated to Duncker, the birds learn to sing when the cage doors are opened, although there is a bit more to it than a simple conditioned reflex.

The amount of light the bird experiences regulates, via its hormones, the amount and quality of its song. One roller breeder told me that if he were to keep his competition birds in an ordinary cage or aviary they would be over-stimulated by the light and sing too much – what he called ‘screaming’. Roller experts also use diet to regulate their birds’ performance. Most canaries are fond of minced hard-boiled egg and many breeders feed this to their birds, especially during the breeding season. But for a roller breeder, a diet containing egg is a disaster since, for some reason, it causes the birds to sing flat. You can also enhance the singing ability of an underachieving bird by feeding it tonic seed and subdue an overeager singer by feeding it poppy seed (maw).

Male displays like plumes or chorister voices would be pointless if females did not possess the mental ability to assess and grade them. In much the same way those who judge the products of artificial selection need to be up to the job. It required relatively modest neural circuitry for men to grade big-buttocked cattle, but judging roller canaries takes immense skill. One needs a very good ear and years of training to become a roller canary judge. I have listened to roller canaries going through their ‘tours’, as they are called, while a top judge explained each component to me. I was embarrassed to find the ‘glucks’, ‘bell rolls’ and ‘flutes’ almost impossible to distinguish.

After a year of friendship, Duncker and Reich decided in 1922 to go public and present Reich’s best birds to the newly formed national committee for judging canary song, the Deutsche Einheitsskala, in Kassel. Reich’s birds were unanimously acclaimed by the judges who had never heard anything like them before. Backed by this official approval Duncker wasted no time in publicising his own ingenious interpretation of Reich’s achievement. He wrote articles for several different magazines, spanning the full range of bird enthusiasts, from the amateur canary keepers to evolutionary biologists. In so doing Duncker not only thrust Reich’s birds into the public eye, he also placed himself in the scientific spotlight. This was no whim, but rather a carefully orchestrated strategy. In a paper he published in the premier German bird journal, Journal für Ornithologie, Duncker described the extraordinary nature of Reich’s self-sustaining strain of birds. He explained that the birds no longer needed a nightingale tutor and then restated Reich’s view that through careful breeding his canaries had been permanently modified by hearing nightingale song. How could this have happened? Duncker then played his trump card. Rather than selecting for the nightingale song itself, which is what Reich believed he had done, in fact he had unconsciously selected birds for their genetic ability to learn the song from their nightingale-canary tutors. This was a brilliant and original explanation. As Duncker reminded his readers, there was no mechanism by which one bird’s genes could be modified by the sound of another. Reich’s Lamarckian style of inheritance simply did not work. Duncker’s idea, on the other hand, was rooted firmly in a straightforward Darwinian-Mendelian process.21

Confident that he was correct, Duncker spelled out exactly how his idea could be tested: one could take some of Reich’s birds and rear them either with ordinary canaries or in a situation where they could hear no other birds. If birds reared in either of these ways subsequently sang a nightingale song then Reich’s Lamarckian view would be right, but if they sang anything else, Duncker’s hypothesis would be confirmed.

Duncker was so far ahead of his time that this part of his collaboration with Reich has been completely overlooked by all subsequent birdsong scholars. Twenty years later when song learning in birds caught the attention of the new field of animal behaviour, a single tangential, slightly deprecating reference to Reich’s work appeared in Julian Huxley’s Modern Synthesis (one of the most influential biology textbooks of the 1940s).22 In a footnote on page 305, Huxley says that Ernst Mayr – student of Erwin Stresemann and later the grand old man of evolutionary biology – had told him about a study in which canaries had been taught to sing using recordings of nightingale song ‘carried out by a fancier named Reich, but complete proof was not supplied’. So near and yet so far! Even in the 1950s and 1960s the great pioneers of song learning, Bill Thorpe and Peter Marler, failed to notice Duncker’s ingenious interpretation of Reich’s wonderful experiment. To this day, many professional ornithologists continue to look down on amateur bird keepers, partly because bird keeping is déclassé and partly out of intellectual snobbery.

Fortunately, other aspects of Duncker’s and Reich’s collaboration were more successful in breaching the barricades of science.