We must, however, acknowledge, as it seems to me, that man with all his noble qualities, still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin.

CHARLES DARWIN, THE DESCENT OF MAN

THE DESCENT OF MAN

In On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, Charles Darwin never discusses the fossil record of human evolution. Even in The Descent of Man, which appeared in 1871, human fossils are never mentioned. There was a good reason for this silence: in the mid-nineteenth century, only a few artifacts suggested prehistoric peoples. The first well-described Neanderthals were found in 1856 in a limestone quarry in the Neander Valley near Düsseldorf, Germany, only three years before On the Origin of Species was published. The fossils consisted of only a skullcap and a few limb bones, and they were originally mistaken for those of a cave bear. Later, the fossils were widely misinterpreted as the remains of a diseased Cossack cavalryman or were given other bizarre mistaken identifications. Nobody considered them anything more than the bones of an unusual modern human. The earliest complete Neanderthal skeleton, from La-Chapelle-aux-Saints in France, happened to be that an old diseased individual with rickets, so the early reconstructions falsely showed Neanderthals as stooped and brutish, rather than upright and powerfully built, as we have learned from many better skeletons found since then.

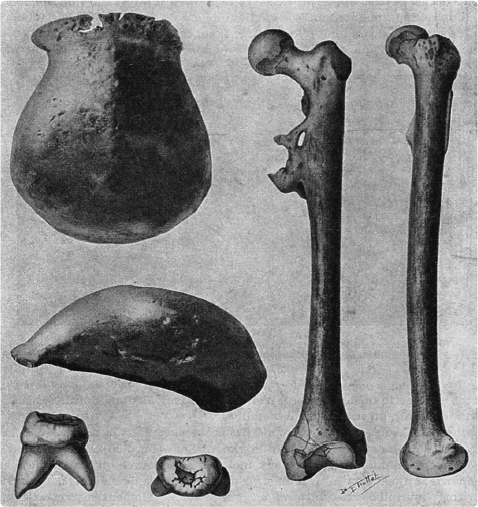

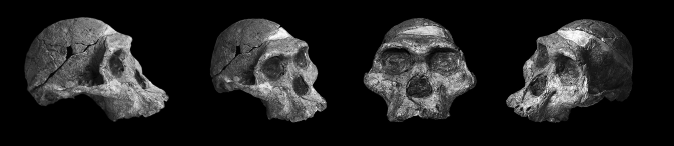

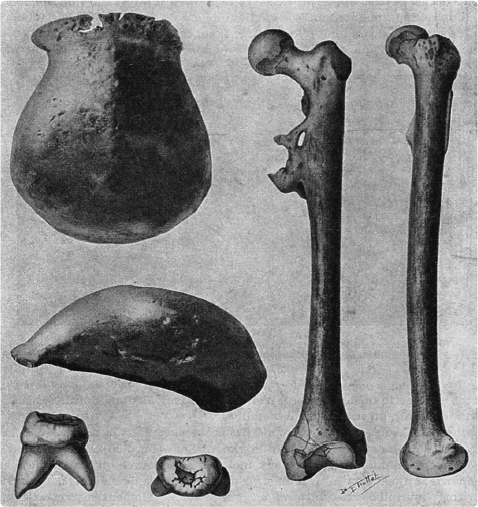

Figure 25.1

Three fossils of “Java man,” as originally drawn by Eugène Dubois: the top of the skull, a molar, and a thigh bone, each in two views. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

The nineteenth century was nearly over before specimens of hominins more primitive than Neanderthals were discovered. The Dutch doctor and anatomist Eugène Dubois was fascinated with Darwin’s ideas and convinced that humans had evolved in eastern Asia, so in 1887 he volunteered for the Dutch army as a surgeon, to be posted the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia). Sure enough, he was extraordinarily lucky. After a few excavations, he hit the jackpot. It turned out that there were fossil hominins in the region, and between 1891 and 1895, he and his Javanese crews found a series of specimens, including a skullcap, a thighbone, and a few teeth (

figure 25.1). He called them

Pithecanthropus erectus (Greek for “upright ape-man”), but they came to be known as “Java man” after the island on which they had been found. Although the specimens were incomplete, it was clear from the thighbone that the creatures had walked upright. The skullcap was very primitive, with prominent brow ridges, yet the cranial capacity was about half that of modern humans.

Dubois returned to Holland and received a professorship in 1899. Unfortunately, he did not handle the normal harsh criticism from the scientific community very well. Many anthropologists were not convinced of Dubois’s claims from such incomplete material, and thought that the fossils were from a deformed ape. As a result, Dubois withdrew from the debate, an angry and bitter man. He hid his specimens away and refused to show them to anyone or to get involved in the scientific discussion. By the 1920s, opinion was turning in his favor, but he remained withdrawn and embittered until his death, at age 82, in 1940.

OUT OF EURASIA?

In 1871, Darwin argued that humans must have evolved from roots in Africa. His reasoning was simple: all our closest ape relatives (chimpanzees and gorillas) live there, so it makes sense that the common ancestor of apes and humans originated in Africa. But most later anthropologists rejected Darwin’s suggestion, insisting that humans had appeared in Eurasia. A number of reasons were given, including Dubois’s discoveries in Java, but underlying their view was a deeply held racism that regarded African peoples as sub-human and not even members of our species. The idea that all humans had descended from black Africans was abhorrent to many white scholars in the early twentieth century.

Nearly all the anthropologists and paleontologists in the early twentieth century thought that the homeland of humanity was Eurasia. The prominent paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, director of the American Museum of Natural History, organized and funded the legendary Central Asiatic Expeditions to Mongolia in the 1920s, under the leadership of Roy Chapman Andrews, on the premise that they would find the oldest human ancestors (

chapter 23). They didn’t, but they did discover very important dinosaur fossils (including the first dinosaur eggs and nests), as well as really interesting and unusual fossil mammals. Eugène Dubois’s discoveries of fossil hominins in Java helped confirm the “out-of-Asia” notion.

In 1921, while the American Museum expedition began to explore Mongolia, the Swedish paleontologist Johann Gunnar Andersson found a cave called Choukoutien (Pinyin, Zhoukoudian) near Beijing. The Austrian paleontologist Otto Zdansky took over the excavations, which yielded an excellent fauna of Ice Age mammals, including a giant hyena and two teeth of a hominin. Zdansky gave the specimens to Canadian anatomist Davidson Black (then working at Peking Union Medical College), who published them in 1927 and called them

Sinanthropus pekingensis (Chinese human from Peking), popularly referred to as “Peking man.”

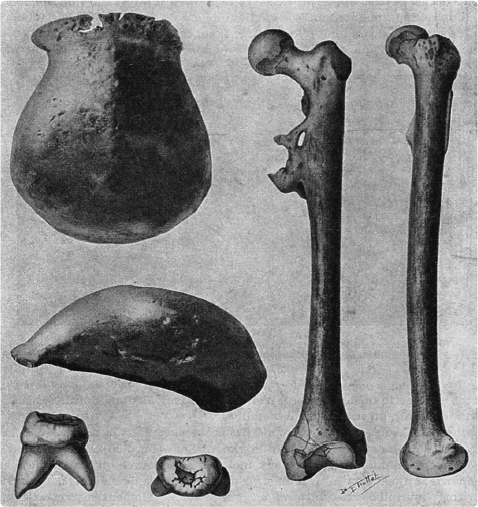

The excavations continued after funding was obtained, with only a few more teeth to show for many years of work. Finally, in 1928, the workers found a lower jaw, skull fragments, and more teeth, and the primitive nature of the species was confirmed. This brought new funding, which prompted a much larger excavation with mostly Chinese workers and scientists. Soon they had unearthed more than 200 human fossils, including six nearly complete skulls (

figure 25.2). Black died of heart failure in 1934, and a year later, the German anatomist Franz Weidenreich took over the study and description of the fossils. Although Black had published many preliminary descriptions of the fossils as they were found, it was Weidenreich’s detailed monographs that gave complete documentation of them. With this material, it soon became apparent that “Peking man” was very similar to “Java man,” and most anthropologists consider them to be the same species:

Homo erectus.

As the excavations at Zhoukoudian continued, war clouds were gathering on the horizon. The Japanese Empire was expanding, and Japan began to attack and annex parts of China, piece by piece. In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria, the northeastern part of China, and turned it into a Japanese province, Manchukuo. Japan set up a puppet government headed by Puyi, the last emperor of China. In 1937, the second Japanese invasion of China began; and the Japanese annexed another large chunk of China as they fought the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek, and the Communists under Mao Zhedong.

Then in 1941, just before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the alarmed scientists in Beijing could sense that war was coming. The crews at Zhoukoudian were afraid that the fossils would fall into Japanese hands and become war souvenirs, rather than specimens preserved for scientific study. They packed all the specimens at Peking Union Medical College into two large crates, loaded them onto a U.S. Marine Corps truck, and tried to smuggle them out of the country through the port of Qinhuangdao. Somewhere in the secretive scramble to avoid the Japanese invaders, the crates were lost and have never been found. Some say that they were loaded onto a ship that was sunk by the Japanese. Others suggest that they were secretly buried to avoid discovery, and no one knows where they are. Still others think that Chinese merchants who routinely destroy fossils (“dragon bones”) and grind them up for traditional “medicine” found them. Fortunately, nearly all the original material was molded, cast, and made into accurate replicas that are housed in many museums, so we know what they look like in detail. In addition, more recent excavations have yielded much more material, so the loss was not irreparable.

Figure 25.2

One of the more complete skulls of “Peking man,” from Zhoukoudian, China. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

The idea that Asia is the original homeland of humanity goes all the way back to the famous German embryologist and biologist Ernst Haeckel, who forcefully argued the point (long before any fossils could test it). Even though Haeckel was Darwin’s greatest protégé in Germany, he disagreed with Darwin’s contention that humans had emerged and evolved in Africa. Haeckel directly inspired Dubois, who appeared to have offered evidence to support the view when he found fossil hominins in Java. The other pioneering anthropologists and paleontologists who agreed with Haeckel included not only those working in Zhoukoudian—Andersson, Zdansky, Black, and Weidenreich—but also Osborn and his colleagues at the American Museum of Natural History: paleontologists Walter Granger (who was the chief scientist of the Central Asiatic Expeditions), William Diller Matthew (who argued that most mammalian groups arose in Eurasia and then spread from that center of origin), and William King Gregory.

At that time, the fossil record seemed to support the notion of the Eurasian origin of humans, first with Neanderthals and then with “Java man” and “Peking man.” And, surprisingly, a discovery in England seemed to confirm that Eurasia had been the primary center of human evolution. At a meeting of the Geological Society of London in 1912, an amateur collector named Charles Dawson claimed that four years earlier a worker in a gravel pit near Piltdown had given him a skull fragment. The worker thought that the skullcap was a fossil coconut and tried to break it, but Dawson returned to Piltdown again and again and found more pieces. Then he showed them to Arthur Smith Woodward of the British Museum of Natural History, who accompanied Dawson to the Piltdown site. Dawson supposedly came upon more pieces of the skullcap and a partial jaw, although Woodward found nothing.

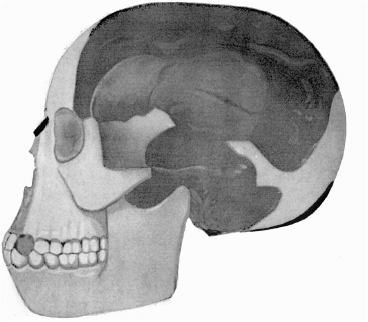

Woodward soon produced a reconstruction of the skull and jaw, based on the few pieces that were available (

figure 5.3). The specimens were very curious. The skull seemed to be very much like that of a modern human, with a bulging cranium, a large braincase, and small brow ridges. However, the jaw was extremely ape-like. Crucially, the hinge of the jaw was broken and missing, as was the face and many parts of the skull, so there was no way to tell if the jaw fit properly with the skull. In August 1913, Woodward, Dawson, and French priest and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin went back to the Piltdown spoil piles, where Teilhard found a canine tooth that fit into the gap between the broken parts of the jaw. The canine was small and human-like, not the large fang-like canines typical of most apes.

Figure 25.3

The skull of “Piltdown man,” as reconstructed by Arthur Smith Woodward. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Dawson’s discovery and Woodward’s reconstruction were not unchallenged, however (

figure 25.4). Anatomist Sir Arthur Keith disputed the reconstruction and made one that was much more human-like. Anatomist David Waterston of King’s College London decided that the two specimens could not belong together and that “Piltdown man” was just an ape jaw attached to a human skull. This was also suggested by French paleontologist Marcellin Boule (who had described the Neanderthals from La-Chapelle-aux-Saints) and American zoologist Gerrit Smith Miller. In 1923, Franz Weidenreich (who had described “Peking man”) argued strongly that “Piltdown man” was a modern human skull and an ape jaw, with the teeth filed off so their ape-like appearance was masked.

Although there were always critics of and doubters about “Piltdown man” in the 1920s and 1930s, the pillars of British paleontology (especially Woodward, Keith, and Grafton Eliot Smith) were firm believers (see

figure 25.4). Despite its problems, the “fossil” fit all their prejudices. First, it seemed to suggest that human evolution had been driven by the enlargement of the brain, long before our ancestors lost their ape-like teeth and jaws, or began to walk on two legs. This was the accepted dogma of paleoanthropology at the time: the large human brain and intelligence came first, and intelligence drove human evolution. The second factor was simple chauvinism. The British were proud that the “missing link” had been found on their soil, the “first Briton” being even more primitive than “Java man” and “Peking man.” Thus it appeared that Europe (especially the British Isles) had been the center of human evolution. The “fossil” fit so perfectly with the biases and myths of anthropology at the time that the questioning soon died down, and “Piltdown man” remained an iconic specimen for 41 years.

It was not until the late 1940s and early 1950s that people began to revive the questions about the specimen, because by then it no longer fit into the fossil record, which was becoming better and better known, especially in Africa. For decades, the Piltdown specimens were kept under lock and key, and only a set of replicas was made available for study, so few people saw the originals close up. Then in 1953, chemist Kenneth Oakley, anthropologist Wilfred E. Le Gros Clark, and Joseph Weiner examined the original “fossils.” They confirmed that “Piltdown man” was a hoax: the skull was from a modern human, excavated from a medieval grave; the jaw was from a Sarawak orangutan; and some of the teeth were from chimpanzees. All the specimens had been stained with a solution of iron and chromic acid to make them look old, and the teeth had been deliberately filed to make them look less ape-like—as Weidenreich had surmised.

Figure 25.4

John Cooke, A Discussion of the Piltdown Skull (1915): this famous painting shows members of the British anthropological community studying the specimen of “Piltdown man”: (front row, center) Sir Arthur Keith (in white coat), its chief advocate; (back row, left to right) F. O. Barlow, Grafton Elliot Smith, Charles Dawson (who planted the forgery), and Arthur Smith Woodward (curator of geology at the Natural History Museum, who formally described it); (front row, left) A. S. Underwood; (front row, right) W. P. Pycraft and the famous anatomist Ray Lankester. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

The identity of all of those involved in the conspiracy is still debated. Charles Dawson, of course, “found” all the “fossils,” and further investigation into his past showed that he had had a long history of forging artifacts and human fossils, so he could have been the sole culprit. Some have argued that he needed expert guidance from an anatomist or anthropologist to make such a successful fraud, strategically breaking off all the parts that would demonstrate that the jaw and the skull did not belong together. At various times, scholars have suggested that Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Arthur Keith, the zoologist Martin A. C. Hinton, the prankster and poet Horace de Vere Cole, or even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle of Sherlock Holmes fame was also behind it. More than a century has now passed, and all the evidence so far has been inconclusive. All we know is that Dawson was the primary (and maybe only) hoaxer and had a long track record of frauds. Whether someone helped him may never be revealed.

THE TAUNG CHILD AND “MRS. PLES”

While research on the Eurasian roots of humans was being undertaken in the museums and universities of Europe, Africa was a scholarly backwater. Most of its cities were sleepy colonial outposts, without major universities or museums. European (especially British, German, French, Portuguese, and Dutch) scientists visited African colonies to collect and remove important specimens for their museums, but left nothing for the host population, who were considered just crude colonials or ignorant natives.

One of the few countries that was not a primitive outpost for science was South Africa. Thanks to its critical position for all shipping passing around the southern tip of Africa and its enormous wealth in gold, diamonds, and precious metals, it had been settled and Europeanized centuries long before the rest of Africa. As a result, there had been a much greater effort in developing a modern European-style state, by both the British masters and the Dutch settlers, who became the Afrikaners. Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban, Pretoria, and other cities were large and sophisticated. They boasted their own universities and museums, among the few in all of Africa. In addition, South Africa was the second colony in Africa to become independent of its European masters, in 1910, long before most other African colonies became independent in the late 1950s and the 1960s.

Among the European-trained scholars in South Africa was a young Australian, Raymond Dart. He had earned a medical degree from University College London and then emigrated to South Africa, where he took a post in the newly established Department of Anatomy at the University of Witswatersrand in Johannesburg. Upon arriving, he was dismayed to find that the department had no comparative collections of human and ape skulls and skeletons, so essential to teaching anatomy. He announced to his students that there would be a competition to see who could bring in the most interesting bones. One student, the only woman in the class, said that she knew of the skull of a fossil baboon on the mantel of a friend’s house. Although Dart doubted that it was really a baboon (since almost no fossil primates were known in sub-Saharan Africa), when he saw the skull in, he knew that his student was right. The skull had come from the house of the director of the Northern Lime Company, which produced cement from limestone dug from a quarry called Taung. Dart then asked him to send over any other fossils the workers found when blasting in the limestone caves.

One summer morning in 1924, Dart was struggling with his stiff winged collar as he was preparing to be best man and host a friend’s wedding at his house. He heard the sound of two wooden crates dumped on his doorstep and went out to investigate. The first contained nothing of interest, but when he pried open the second, there was a beautiful braincase with a natural endocranial cast of the brain, right on top! Excitedly, he rummaged around until he found the face that had been attached to the braincase. He could already tell that the brain was much larger than a chimpanzee’s, even though the skull was the same size. His friend, the groom, urged him to finish dressing. During the entire ceremony, Dart could not wait to get back to his “treasures.” Over the next few months, he cleaned and prepared the specimen and, with one delicate stroke using a hammer and knitting needles, split off the matrix from the front of the face.

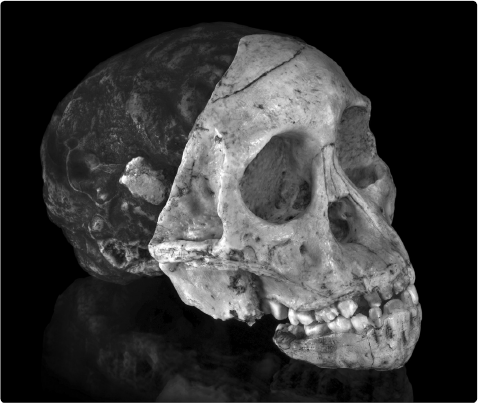

Figure 25.5

Side view of the skull of Australopithecus africanus known as the Taung child. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

The face that emerged was that of a child of about four years, with all its baby teeth still in place (

figure 25.5). Although the skull is about the size of that of a modern chimpanzee, it has a number of hominin-like features, including an unusually large brain, a flat face with no snout and small brow ridges, and reduced canine and human-like teeth arranged in a semicircle in palatal view. Most important, the hole in the base of the skull for the spinal column (foramen magnum) is directly below the brain, proving that this creature held its head up and probably walked upright.

Dart wrote his description and analysis and published it in

Nature, the preeminent scientific journal in the world, in 1925. He called the specimen

Australopithecus africanus (Greek for “African southern ape”), and it clearly shows that early hominins lived in Africa, especially since it is far more primitive and ape-like than any fossil that had been found so far. Since Dart had studied brain endocranial casts in medical school, he was particularly interested in the natural endocast on this specimen.

Australopithecus had not only a brain far larger than any ape brain for a skull of that size, but a noticeably more advanced forebrain, like that of humans but not apes.

Dart thought that his evidence was conclusive, and he expected to receive accolades from the scientific community, Instead, he was disappointed to see all the great anthropologists in Europe dismiss his specimen as a “juvenile ape.” Part of the problem is that juvenile apes do look a lot more like modern humans than do adult apes. Still, the upright posture, the hominin-like cheek teeth, the reduced canines and semicircular arrangement of teeth around the palate, and the enlarged forebrain were not artifacts of the youth of the specimen.

But the Taung child was running up against a wall of false notions and prejudice. As we have seen, British and other European anthropologists were convinced that a large brain evolved first, followed by smaller teeth and upright posture in hominins. And they had the skull of “Piltdown man,” with a human-like brain but ape-like teeth, to prove it. But the Taung child showed just the opposite: a relatively small brain, but upright posture and hominin-like teeth with reduced canines. Thus it could not be accepted. Sir Arthur Keith, one of Piltdown’s biggest backers, wrote: “[Dart’s] claim is preposterous, the skull is that of a young anthropoid ape…and showing so many points of affinity with the two living African anthropoids, the gorilla and chimpanzee, that there cannot be a moment’s hesitation in placing the fossil form in this living group.”

In addition, there were other unspoken factors: imperialism and racism. The top scholars in Europe did not trust the conclusions of Dart, an obscure anatomist in remote South Africa (even though he had trained in London)—not a recognized expert, but a “country bumpkin.” His paper in Nature was very short (as they always must be), so the leading paleontologists had only a brief description and a few tiny hand-drawn figures by which to judge the specimen. (Dart later wrote a more detailed description, especially of the brain.) But no one had the time, money, or inclination to take the long sea voyage to South Africa in order to examine the fossil.

So Dart brought it to them. In 1931, he visited Britain and brought the Taung child with him, but to no avail. The racial prejudices of British anthropologists were just too deeply entrenched. In addition, the excitement over the skull of “Peking man” was just reaching Europe as Davidson Black’s illustrations and descriptions were published—supporting the earlier evidence for a Eurasian origin offered by “Java man” and “Piltdown man”—so the poor Taung child, the only specimen from Africa, and Dart were overshadowed.

Dart would wait another 20 years before the European anthropological community stopped dismissing him and began to recognize the importance of his find. In 1947, Keith admitted that “Dart was right and I was wrong.” But Dart had the last laugh. He lived until 1988, dying at the age of 95, celebrated and honored for his discoveries and for pioneering modern paleoanthropology, while most of his bitter rivals died long before him and are now forgotten.

But in the 1920s and 1930s, other South African scientists were convinced that Dart was right and was being unfairly criticized. Among them was the Scottish-born doctor Robert Broom (

chapter 19), who had already made a reputation for himself as an important paleontologist by finding spectacular specimens of Permian reptiles and of the earliest relatives of mammals in the Great Karoo. Some in his network of collectors sent him fossils they had found in the many limestone caves in South Africa. Working in a cave called Kromdraai in 1938, Broom discovered a very robust adult skull he called

Paranthropus robustus (Greek for “robust near-human”). Later, in the famous cave complex at Swartkrans, he found fossils of more than 130 individuals of

P. robustus. A recent analysis of their teeth showed that none of these robust, gorilla-like humans lived past 17 years and that they subsisted on a gritty diet of nuts, seeds, and grasses.

Also in 1938, Broom obtained an endocranial cast of a fossil skull with a capacity of 485 cc, far too large to be that of an ape. He called this specimen

Plesianthropus transvaalensis (Greek for “near ape of the Transvaal”). Then he heard word of fossils coming from a cave called Sterkfontein. On April 18, 1947, Broom and John T. Robinson found the complete skull of what was then considered to be an adult female (now thought to be male) that demonstrated hominin features, yet it was just as primitive as the Taung child (

figure 25.6). They nicknamed this specimen “Mrs. Ples,” and their discovery showed that South Africa was yielding fossils of hominins that were much more primitive than any that had been found anywhere in Eurasia. Soon other fossils emerged from Sterkfontein, establishing the variability of the population of

Plesianthropus transvaalensis. Later anthropologists decided that the Sterkfontein adults and the Taung child are the same species, so

Plesianthropus transvaalensis is now subsumed under Dart’s original taxon:

Australopithecus africanus.

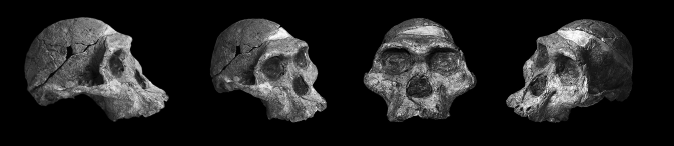

Figure 25.6

Multiple views of the most complete skull of Australopithecus africanus, nicknamed “Mrs. Ples.” (Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

These discoveries in Africa—along with the complete absence of fossils so primitive or ancient in Eurasia—began to shift the momentum of the debate away from the “out-of-Asia” school of thought. The wide spectrum of australopithecines that had been described by 1947 made it appear more and more likely that Darwin was right: humans had originated in Africa. Not only that, but the idea that brains and intelligence drove human evolution, but small teeth and upright posture came later, was also dying (as the older generation of racist anthropologist died off as well). Every fossil found so far demonstrated that upright posture and advanced teeth had evolved first, and the brain began to enlarge much later. So in 1953, when someone decided to examine “Piltdown man” closely, since it no longer fit the emerging picture of human evolution, the hoax finally was exposed—both an embarrassment and a relief.

LEAKEY’S LUCK

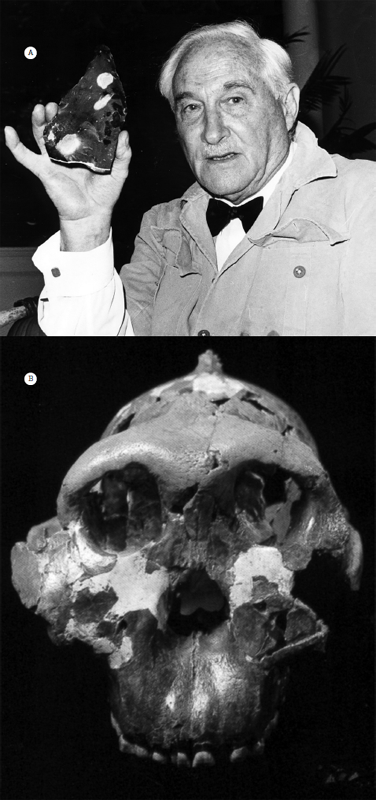

Another advocate of the “out-of-Africa” hypothesis was the legendary Louis S. B. Leakey (

figure 25.7A). By all accounts, he was a charismatic, ebullient, outspoken man who could weave a tremendous tale about his discoveries. Critics also considered him to be somewhat careless and sloppy in his science, and occasionally known for buying into controversial ideas that did not pan out. Nonetheless, he left a permanent legacy in the study of human evolution—not only for discovering many famous fossils, but also for training his wife, Mary (who made most of the discoveries), and his son Richard (who outshone his father) and for mentoring many other important anthropologists. He also inspired primatologists like Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Birute Galdikas to spend years studying wild chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, respectively.

Born into a family of British missionaries in what is now Kenya, Leakey grew up with the wildlife of East Africa and became fluent in the language and culture of the Kikuyu, one of the largest tribes in that region. Although he was partially educated by tutors in Kenya, after World War I he was sent to Cambridge, where he proved to be a brilliant and eager but often eccentric student. He chose a career in anthropology and was already publishing numerous papers on the archeology of Kenya in his twenties. In the early 1930s, his career was nearly derailed when he abandoned his first wife, Frida, after he fell in love with his artist, young Mary Nicol. To escape the censure of the academic community, he and Mary returned to Kenya, where they found a number of sites with primitive apes at Kanam, Kanjera, and Rusinga Island.

While in Kenya before and during World War II, his fluency in the Kikuyu language and his good connections with the native cultures made him an important figure in the politics of the region, not only as a spy during the war, but also as an interpreter and a go-between during tensions between the British and the Kikuyu. He was a key figure in the Mau Mau Revolt and eventually helped resolve the disputes. But he refused to return to Europe, settling instead for a tiny salary at the Coryndon Museum in Nairobi (now the National Museum of Kenya).

Leakey’s reputation and finds in Africa were significant, but he was still struggling to discover something spectacular that would not only confirm that humans had indeed arisen and evolved in Africa, but also launch his career and ensure better funding for his work. The specimens in South African caves were important, but they could not be numerically dated. What was needed was a locality where the hominin fossils were buried in the sediment with age-diagnostic mammal fossils and with volcanic ashes that could provide numerical dates.

Figure 25.7

(A) Louis S. B. Leakey, holding an artifact; (B) front view of the skull called “Zinjanthropus” (now Paranthropus boisei), which made the Leakeys world famous and drove research on paleoanthropology back to Africa. ([A] courtesy Wikimedia Commons; [B] courtesy National Museums of Kenya)

In 1913, German archeologist Hans Reck had excavated a fairly modern human skeleton from Bed II of Olduvai Gorge in what is now Tanzania. His find was controversial, since it appeared to be from the middle Pleistocene, much older than European fossils of that level of human evolution. In 1931, Leakey became involved in the debate and managed to convince his colleagues that Reck’s specimen was not a modern human buried in ancient strata. In 1951, once World War II and postwar politics were over and he had more time for anthropology, Louis and Mary began full-time work in the lowest levels of Olduvai Gorge. They found many stone tools indicating cultures much more primitive than those in Europe, but no convincing fossils.

Then in 1959, after eight years of hard work (and 30 years after Louis had first worked at Olduvai), Mary found an extraordinary fossil skull (see

figure 25.7B). It was much more primitive and robust than anything ever unearthed in South Africa or elsewhere, and it came from Bed I, the lowest level in Olduvai Gorge. The spectacular skull was nicknamed “Dear Boy” by the Leakeys and formally named

Zinjanthropus boisei, or “Zinj” for short. (The genus nickname was the name of a medieval African region, and the species name honors Charles Boise, who funded their research.) Then in 1960, Jack Evernden and Garniss Curtis applied the newly developed technique of potassium-argon dating to an ash layer above Olduvai Bed I and got an age of more than 1.75 million years, far older than anyone believed possible. At that time, most scientists thought that the entire Pleistocene was only a few hundred thousand years old, but the entire timescale was recalibrated in the 1960s with the introduction of more potassium-argon dates. Soon the Leakeys were world famous and championed by the National Geographic Society, which funded their work. More important, anthropologists swarmed to Africa to find more specimens, since it was clear that most of human evolution had indeed occurred in Africa. Only much later did humans migrate to Eurasia and beyond.

LUCY’S LEGACY

The rush to find hominins from the “Dark Continent” soon spread across East Africa, especially in regions with long sedimentary records in fault basins along the Great Rift Valley. Louis Leakey’s son Richard, who was initially uninterested in anthropology, eventually adopted his father’s mantle. Seeking to escape his father’s shadow, he began to excavate in Lake Rudolf (now Lake Turkana) in northern Kenya in the 1970s. There, many more skulls were found, including the best-preserved specimen of

Homo habilis, the oldest species in our genus,

Homo. Richard moved on to prominent positions in the Kenyan government (especially fighting the poaching of rhinos and elephants). His wife, Meave, working with local people, carried on the Leakey legacy. His mother, Mary, continued to make significant finds, especially the spectacular trackway of hominins at Laetoli in Tanzania.

Kenya and Tanzania were in the news almost every year with the spectacular finds of the Leakeys. In the late 1960s, Louis Leakey had lunch with President Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya and Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. The emperor asked Leakey why there had been no discoveries in Ethiopia. Louis quickly persuaded him that fossils would be found if he gave the order to let scientists explore for them. Soon anthropologist F. Clark Howell of Berkeley was working on the northern shore of Lake Turkana, where the Omo River flows out of Ethiopia. Howell and his colleague Glynn Isaac spent many years collecting in the Omo beds, which have abundant volcanic ash dates. Unfortunately, these deposits were formed in flash floods that produced gravelly and sandy streams, which tend to break up and abrade fossils, so no well-preserved hominin specimens were found.

Meanwhile, other rising young anthropologists were eager to make their own discoveries in a region that had been almost exclusively the territory of the Leakeys and their allies. Two of them were Donald Johanson and Tim White. Both were seeking to make their professional fortunes by exploring sites not under the control of the Leakeys. Through French geologists Maurice Taieb and Yves Coppens and anthropologist Jon Kalb, they learned about beds in the Afar Triangle, the rift valley that is opening between the tectonic plates where the Gulf of Aden meets the Red Sea. These beds already had yielded numerous fossils of mammals, suggesting that they were at least 3 million years old, which made them potentially older than any hominin fossil found so far in Kenya or Tanzania. Johanson, White, Taieb, and Coppens received permission to work in these beds and began to excavate at Hadar in 1973.

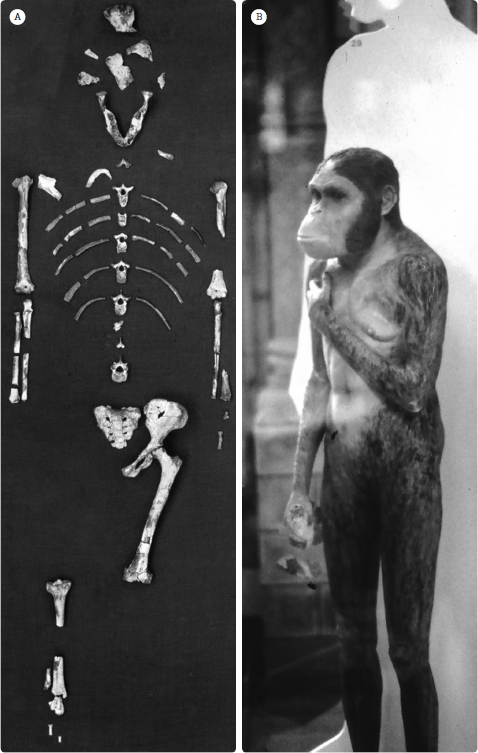

After months of exploring and prospecting for fossils, and finding a few hominin fragments, on November 24, 1974, Johanson took a break from writing field notes to help his student Tom Gray search an outcrop. He spotted the glint of bone out of the corner of his eye, dug out the fossil, and immediately recognized that it was a hominin bone. They continued to unearth more and more bones, until they found almost 40 percent of a skeleton of a hominin (

figure 25.8A). It was the first skeleton, rather than isolated bones, found of any hominin older than the Neanderthals of the late Pleistocene. That night as they celebrated over the campfire, they were playing a tape of the Beatles when “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” came on. Singing lustily along, a member of the crew named Pamela Alderman suggested that the fossil be nicknamed “Lucy.” Later, it was formally named

Australopithecus afarensis, in reference to the Afar Triangle, where it was found.

A year after the discovery of “Lucy,” the crew returned to Hadar, where they found a large assemblage of A. afarensis bones. Nicknamed the “First Family,” it was the first large sample of fossils of both juvenile and adult hominins from beds dating to 3 million years ago, and it gave anthropologists a look at how much variability was typical in a single population. This can be important when deciding whether a newly discovered fossil that is slightly different from specimens found earlier should be considered a new species or genus or just a member of a variable population.

When the analysis of “Lucy” was conducted, Johanson and White determined that the skeleton was that of an adult female that had stood about 1.1 meters (3.5 feet) tall (see

figure 25.8B). The most important evidence was the knee joint and the hip bones, which show the critical features that prove that

A. afarensis walked upright with its legs completely beneath its body, as do modern humans. It had a relatively small brain (380 to 430 cc) and small canines, like those of advanced hominins, yet still had a pronounced snout, rather than a flat face. This was yet another blow to the “big brains first” theory of human evolution, which was still in vogue in the mid-1970s. Its shoulder blade, arms, and hands are quite ape-like, however, so

A. afarensis still climbed trees, even if it was fully bipedal. Yet the foot shows no signs of a grasping big toe, so its legs and feet were adapted entirely for walking on the ground and its toes could not grasp branches.

Since the discovery of “Lucy” in the mid-1970s, paleoanthropologists have made many more amazing discoveries. “Lucy” was the first ancient hominin (older than 3 million years) known from a skeleton, rather than from a partial skull or a few isolated limb bones. In 1984, Alan Walker and the Leakey team found the “Nariokotome boy” on the shores of West Turkana. About 1.5 million years in age, the skeleton is 90 percent intact and thus is the most complete ancient hominin ever found. It may belong to

Homo erectus or

H. ergaster (its identity is still controversial). And in 1994, White and his crew found a nearly complete skeleton of

Ardipithecus ramidus in Ethiopia, which dates to 4.4 million years.

Figure 25.8

Lucy, an Australopithecus afarensis: (A) skeleton; (B) reconstruction of her appearance in life. ([A] courtesy D. Johanson; [B] photograph by the author)

Thus the fossil record of hominins gets better year after year, as more and more specimens are found. In a century, we have come an enormous distance from when the only ancient hominins known were Neanderthals, “Java man,” and “Peking man” and when “Piltdown man” was still taken seriously. Today, there are six genera of hominins besides Homo (Ardipithecus, Australopithecus, Kenyanthropus, Orrorin, Paranthropus, and Sahelanthropus), and more than 12 valid species. From the simplistic idea of a single human lineage evolving through time, the fossil record has revealed a complex, bushy branching pattern of evolution, with multiple lineages coexisting in time and place.

For only the past 30,000 years has there been a single species of hominin dominating the planet. Now Homo sapiens threatens to wipe out nearly every other species, as well as itself, making them just as extinct as the fossils described in this book.

SEE IT FOR YOURSELF!

The original fossils of Ardipithecus, Australopithecus, Homo habilis, H. erectus, and other earliest hominins are kept in special protected storage in the museums of the countries from which they came (mainly, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Chad). Only qualified researchers are allowed to view these collections or to touch these rarest of treasures.

Many museums have exhibition halls devoted to human evolution, featuring high-quality replicas of the most important fossils. In the United States, they include the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago; National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles; San Diego Museum of Man; and Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. In Europe, they include the Natural History Museum, London; and Museum of Human Evolution, Burgos, Spain. Farther afield is the Australian Museum, Sydney.

Boaz, Noel T., and Russell T. Ciochon. Dragon Bone Hill: An Ice-Age Saga of Homo erectus. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Dart, Raymond A., and Dennis Craig. Adventures with the Missing Link. New York: Harper, 1959.

Johanson, Donald, and Maitland Edey. Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981.

Johanson, Donald, and Blake Edgar. From Lucy to Language. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006.

Kalb, Jon. Adventures in the Bone Trade: The Race to Discover Human Ancestors in Ethiopia’s Afar Depression. New York Copernicus, 2000.

Klein, Richard G. The Human Career: Human Cultural and Biological Origins. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Leakey, Richard E., and Roger Lewin. Origins: What New Discoveries Reveal About the Emergence of Our Species and Its Possible Future. New York: Dutton, 1977.

Lewin, Roger. Bones of Contention: Controversies in the Search for Human Origins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

——. Human Evolution: An Illustrated Introduction. 5th ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004.

Morell, Virginia. Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Humankind’s Beginning. New York: Touchstone, 1996.

Reader, John. Missing Links: In Search of Human Origins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Sponheimer, Matt, Julia A. Lee-Thorp, Kaye E. Reed, and Peter S. Ungar, eds. Early Hominin Paleoecology. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2013.

Swisher, Carl C., III, Garniss H. Curtis, and Roger Lewin. Java Man: How Two Geologists Changed Our Understanding of Human Evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Tattersall, Ian. The Fossil Trail: How We Know What We Think We Know About Human Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

——. Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Wade, Nicholas. Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors. New York: Penguin, 2007.

Walker, Alan, and Pat Shipman. The Wisdom of the Bones: In Search of Human Origins. New York: Vintage, 1997.