Jesus Anointed at Bethany (12:1–11)

On the Friday evening before Passion week, Jesus arrives in Bethany, where a dinner is celebrated in his honor (it is now March, A.D. 33). The next day, “Palm Sunday,” Jesus sets out for Jerusalem and is given a hero’s welcome. The Pharisees are increasingly exasperated, while Jesus’ appeal is shown to extend even to some Greeks who want to see Jesus.

| Jesus’ Final Week (John 12–21; March 27–April 3, A.D. 33) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Time | Location/Event | Passage in John |

|

Friday, March 27, 33 |

Jesus arrives at Bethany |

|

|

Saturday, March 28, 33 |

Dinner with Lazarus and his sisters |

|

|

Sunday, March 29, 33 |

“Triumphal entry” into Jerusalem |

|

|

Monday-Wednesday, March 30–April 1, 33 |

Cursing of fig tree, temple cleansing, temple controversy, Olivet discourse |

Synoptics |

|

Thursday, April 2, 33 |

Third Passover in John; betrayal, arrest |

|

|

Friday, April 3, 33 |

Jewish and Roman trials, crucifixion, burial |

|

Six days before the Passover (12:1). If John, as is likely, thinks of Passover as beginning Thursday evening (as do the Synoptics), “six days before the Passover” refers to the preceding Saturday, which began Friday evening.

A dinner was given in Jesus’ honor (12:2). If Jesus arrives Friday evening, the festivity recounted here probably takes place on Saturday. “Dinner” (deipnon) refers to the main meal of the day. It was usually held toward evening but could commence as early as mid-afternoon, so that there is no perfect correspondence to our terms “lunch” and “dinner” today. Nevertheless, Jesus’ words in Luke 14:12, “when you give a luncheon [ariston] or dinner [deipnon],” show that the midday and the evening meal were distinct. Moreover, “dinner” may refer to a regular meal or to a festive banquet (cf. Matt. 23:6 par.; Mark 6:21). Elsewhere in John’s Gospel, the term is used of the Last Supper (13:2, 4; 21:20). In first-century Palestine, banquets usually started in the later hours of the afternoon and quite often went on until midnight. Banquets celebrating the Sabbath could begin as early as midday.

Martha served, while Lazarus was among those reclining at the table with him (12:2). Martha’s serving at the table may indicate that by this time Sabbath has come to an end. Possibly, the meal is connected with the Habdalah service, which marked the end of a Sabbath (m. Ber. 8:5). It is probable that Lazarus, Mary, and Martha provide the meal, though a large dinner in this small village, celebrated in honor of a noted guest, may well have drawn in several other families to help with the work. “Reclining at the table” may indicate a banquet rather than a regular meal (see 13:2–5, 23).385

Then Mary took about a pint (12:3). A litra (a measurement of weight equivalent to the Latin libra) amounted to about eleven ounces or a little less than three-quarters of a pound (half a liter). Then, as today, this is a large amount of perfume.386

ROMAN ERA GLASS CONTAINERS

Pure nard, an expensive perfume (12:3). See Song 1:12; 4:13–16 (LXX). Nard, also known as spikenard, is a fragrant oil derived from the root and spike (hair stem) of the nard plant, which grows in the mountains of northern India.387 This “Indian spike,” used by the Romans for anointing the head, was “a rich rose red and very sweetly scented.”388 The Semitic expression is found in several papyri, including one from the early first century (P. Oxy. 8.1088.49). The rare term “pure” (pistikēs) may mean “genuine” (derived from pistis, “true, genuine”) in contrast to diluted, since nard apparently was adulterated on occasion. “Perfume” (myron) is used here probably in the generic sense of “fragrant substance” (cf. Mark 14:3). The Synoptic parallels indicate that the perfume was kept in an “alabaster jar” (Matt. 26:7; Mark 14:3).389 For “expensive,” see comments on 12:5.

She poured it on Jesus’ feet (12:3). “Poured” translates the Greek word aleiphō, which literally means “anoint.” Anointing the head was common enough (Ps. 23:5; Luke 7:46), but anointing the feet was unusual (usually simply water was provided), even more so during a meal, which was definitely improper in Jewish eyes. Somewhat similar was the Babylonian custom for women to drip consecrated oil onto the heads of rabbis present at the wedding of a virgin, and for slave girls to bathe the hands and feet of a guest in oil.

The Greek poet Aristophanes cites an instance where a daughter is washing, anointing (aleiphō), and kissing her father’s feet (Vespae 608). In the present instance, it is hard not to see royal overtones in Mary’s anointing of Jesus, especially in light of the fact that the event is immediately followed by Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem, where he is hailed as the king of Israel who comes in the name of the Lord (12:13, 15). Attending to the feet was servant’s work (see comments on 1:27; 13:5), so Mary’s action shows humility as well as devotion.

Wiped his feet with her hair (12:3). The use of hair rather than a towel for wiping Jesus’ feet indicates unusual devotion. The act is all the more striking since Jewish women (esp. married ones) never unbound their hair in public, which would have been considered a sign of loose morals (cf. Num. 5:18; b. Soṭah 8a).390 The fact that Mary (who was probably single, since no husband is mentioned) here acts in such a way toward Jesus, a well-known (yet unattached) rabbi, is sure to raise some eyebrows (see comments on 4:7). Also unusual is the wiping off of the oil.

Worth a year’s wages (12:5). “A year’s wages” translates “three hundred denarii.” One denarius was the daily remuneration of a common laborer (cf. Matt. 20:2; see comments on John 6:7). Three hundred denarii is therefore roughly equivalent to a year’s wages, since no money was earned on Sabbaths and other holy days. This perfume is outrageously expensive owing to its being imported all the way from northern India. Its great value may indicate that Mary and her family are very wealthy. Alternatively, this may have been a family heirloom that has been passed down to Mary.

Money bag (12:6). The expression originally denoted any kind of box to hold the reeds of musical instruments. Later, the term was used for a coffer into which money is cast (2 Chron. 24:8, 10). In the present instance, what may be in mind is therefore not a “bag” (NIV) but a box made of wood or some other rigid material (cf. Plutarch, Galba 16.1; Josephus, Ant. 6.1.2 §11). The money kept in this container probably helps meet the needs of Jesus and his disciples as well as provide alms for the poor. The funds would be replenished by followers of Jesus such as the women mentioned in Luke 8:2–3, who supported his ministry.

It was intended that she should save this perfume for the day of my burial (12:7). While it was not uncommon for people in first-century Palestine to spend considerable amounts in funeral-related expenses, it is unusual that Mary here lavishly pours out perfume on Jesus while he is still alive. The word for burial (entaphiasmos) refers not so much to the event itself as to the laying out of the corpse in preparation for burial (cf. 19:40).

You will always have the poor among you, but you will not always have me (12:8). The allusion is probably to Deuteronomy 15:11: “There will always be poor people in the land.” Jewish sources indicate that care of the dead was to take precedence over almsgiving. b. Sukkah 49b praises gemilut ḥasadim (“the practice of kindness”) above charity, among other reasons because it can be done both to the living and the dead (by attending their funeral; cf. t. Peʾah 4:19).

The Triumphal Entry (12:12–19)391

The next day (12:12). This is probably Sunday of Passion week, called “Palm Sunday” in Christian tradition.

The great crowd (12:12). With Jerusalem’s population at that time being about 100,000 and the amount of pilgrims amounting to several times the population of Jerusalem, the “great crowd” gathered at the Jewish capital at the occasion of the Passover may have numbered up to a million people. Many of these pilgrims were probably Galileans, who were well acquainted with Jesus’ ministry.

The Feast (12:12). Passover (see 12:1 above and comments on 2:13).

Palm branches (12:13). Date palm trees did grow in the vicinity of Jerusalem, especially Jericho, the “City of Palms” (Deut. 34:3; 2 Chron. 28:15).392 The palm tree served as a symbol of righteousness: “The righteous will flourish like a palm tree” (Ps. 92:12). In the Old Testament, palm branches are associated not with Passover but with the Feast of Tabernacles (Lev. 23:40). However, by the time of Jesus palm branches had already become a national (if not nationalistic) Jewish symbol (Josephus, Ant. 3.10.4 §245; 13.13.5 §372; cf. Jub. 16:31). Palm branches were a prominent feature at the rededication of the temple in Maccabean times (2 Macc. 10:7; 164 B.C.) and were also used to celebrate Simon’s victory over the Syrians (cf. 1 Macc. 13:51; 141 B.C.). Later, palms appear on the coins minted by the insurrectionists during the Jewish wars against Rome (A.D. 66–70 and 132–135) and even on Roman coins themselves. Apocalyptic end-time visions likewise feature date palms (Rev. 7:9; T. Naph. 5:4).

PALM BRANCHES

A date palm in the Sinai region.

A palm tree is depicted on a coin minted during the Bar Cochba revolt against Rome (c. A.D. 132).

In the present instance, people’s waving of palm branches may signal nationalistic hopes that in Jesus a messianic liberator had arrived (cf. 6:14–15).393 A later rabbinic source reads, “It is the one who takes the palm branch in his hand who we know to be the victor” (Lev. Rab. 30:2). The Greco-Roman world knew palm branches as symbols of victory (e.g., Suetonius, Caligula 32: “ran about with a palm branch, as victors do”).

Went out to meet him, shouting, “Hosanna!” (12:13). See Psalm 118:25. The phrase “went out to meet him” (rare in biblical literature) was regularly used in Greek culture, where such a joyful reception was customary when Hellenistic sovereigns entered a city. An instance of this is recorded by Josephus when Antioch came out to meet Titus (J.W. 7.5.2 §§100–101). The term “Hosanna,” originally a transliteration of the identical Hebrew expression,394 had become a general expression of acclamation or praise. Most familiar was the term’s occurrence in the Hallel (Pss. 113–18; see esp. 118:25), a psalm sung each morning by the temple choir during various Jewish festivals (cf. m. Pesaḥ. 5:7; 9:3; 10:7). At such occasions, every man and boy would wave their lulab (a bouquet of willow, myrtle, and palm branches; b. Sukkah 37b; cf. Josephus, Ant. 3.10.4 §245) when the choir reached the “Hosanna!” in Psalm 118:25 (m. Sukkah 3:9).

Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! (12:13). See Psalm 118:26. In its original context, Psalm 118 conferred a blessing on the pilgrim headed for Jerusalem, with possible reference to the Davidic king. Later rabbinic commentary interpreted this psalm messianically (Midr. Pss. on Ps. 118:24). Note also the interesting connection between a donkey and the “ruler from Judah” in Genesis 49:11.

Blessed is the King of Israel! (12:13). For the title “King of Israel,” see comments on 1:49.

Jesus found a young donkey and sat upon it (12:14). For a fuller description of how Jesus “found” the donkey, see Matthew 21:1–3 par. Two associations with the donkey were dominant in first-century Palestine: humility (see comments on 13:1–20) and peace (see comments on 14:27). In contrast to the war horse (cf. Zech. 9:10), the donkey was a lowly beast of burden: “Fodder and a stick and burdens for a donkey” (Sir. 33:25; cf. Prov. 26:3). Donkeys were also known as animals ridden on in pursuit of peace, be it by ordinary folk, priests, merchants, or persons of importance (Judg. 5:10; 2 Sam. 16:2). Jesus’ choice of a donkey invokes prophetic imagery of a king coming in peace (Zech. 9:9; cf. 12:10: “He will proclaim peace to the nations”), which contrasts sharply with notions of a political warrior messiah (cf. 1 Kings 4:26; Isa. 31:1–3). The early Christians were often mocked as worshiping a donkey, a man in form of a donkey, or a donkey’s head, such as in the famous graffito of a crucified slave with the head of a donkey and of another slave worshiping with the inscription “Alexamenos worships God” (early 3d cent. A.D.?).395

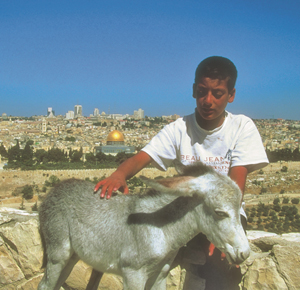

A YOUNG DONKEY IN MODERN JERUSALEM

Do not be afraid, O Daughter of Zion; see, your king is coming, seated on a donkey’s colt (12:15). See Zechariah 9:9. The phrase “Do not be afraid” does not occur in the Hebrew or other versions of Zechariah 9:9, replacing the expression “Rejoice greatly.” It may be taken from Isaiah 40:9, where it is addressed to the one who brings good tidings to Zion (cf. Isa. 44:2; Zeph. 3:16).396 “Daughter of Zion” is a common way of referring to Jerusalem and its inhabitants, especially in their lowly state as the oppressed people of God.

A PALM SUNDAY PROCESSIONAL ON A JERUSALEM STREET

An early messianic prophecy speaks of a ruler from Judah who will command the obedience of the nations and who rides on a donkey (Gen. 49:10–11). Yet the rabbis had difficulty reconciling this notion of a humble Messiah with that of the Danielic Son of Man “coming on the clouds of heaven” (b. Sanh. 98a; c. A.D. 250). However, riding on a donkey does appear as one of the three signs of the Messiah in Eccles. Rab. 1:9 (c. A.D. 300), where the latter redeemer in Zechariah 9:9 is featured as the counterpart to Moses in Exodus 4:20. Note too 1 Kings 1:38, where Solomon (whose name means “peaceable”) rode into Jerusalem for his coronation on King David’s mule.

The whole world has gone after him! (12:19). “The whole world” constitutes a common Jewish hyperbolic phrase. So it is said that “all the world” followed the high priest (b. Yoma 71b); that Hezekiah taught the Torah to “the whole world” (b. Sanh. 101b); that “the people [lit., the world] were flocking to David” (b. B. Meṣi ʿa 85a; cf. 2 Sam. 15:13); and that “all the people [lit., world] came and gathered around” a certain rabbi (b. ʿAbod. Zar. 19b). The early Christians were said to “have caused trouble all over the world” (Acts 17:6).

Jesus Predicts His Death (12:20–36)

There were some Greeks among those who went up to worship at the Feast (12:20). As elsewhere in the New Testament, the term “Greeks” refers not to people literally hailing from Greece, but to Gentiles from any part of the Greek-speaking world, including Greek cities in the Decapolis (see comments on 7:35). Most likely, these “Greeks” were God-fearers who had come up to Jerusalem to worship at the Feast (cf. Acts 17:4: “God-fearing Greeks”). Like the Roman Cornelius (Acts 10) or the centurion who had a synagogue built (Luke 7:5), such God-fearers were attracted to the Jewish way of life without formally converting to Judaism. They were admitted to the court of the Gentiles in the temple but forbidden entrance into the inner courts on the warning of death.

They came to Philip, who was from Bethsaida in Galilee (12:21). See 1:44. It is possible that the “Greeks” singled out Philip—and Andrew—because of their Greek names; although they were both Jews, they were the only two members of the Twelve with Greek names (with the possible exception of Thomas, see comments on 11:16). If these “Greeks” were from the Decapolis or from the territories north or east of the Sea of Galilee (such as Batanea, Gaulanitis, or Trachonitis), they may have known (or found out) who among Jesus’ disciples it was who came from the nearest town—Philip, who hailed from Bethsaida (located in Gaulanitis). Galilee, in fact, was more Hellenized than much of the rest of Palestine and bordered on pagan areas (cf. Matt. 4:15). Moreover, Philip, because of his origin, would have been able to speak Greek.

Philip went to tell Andrew; Andrew and Philip in turn told Jesus (12:22). Philip is mentioned along with Andrew in 1:44 and 6:7–8 (cf. Mark 3:18).

For the Son of Man to be glorified (12:23). See comments on 1:51. The reference to the glorification of the Son of Man may well hark back to Isaiah 52:13, where it is said that the Servant of the Lord “will be raised and lifted up and highly exalted” (LXX: doxasthēsetai). In pre-Christian usage, the glory of the Son of Man and his function of uniting heaven and earth are conceived in primarily apocalyptic terms (Dan. 7:13; cf. 1 En. 45–57, esp. 46 and 48; first century A.D.?).

Unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds (12:24). The principle of life through death is here illustrated by an agricultural example. In rabbinic literature, the kernel of wheat is repeatedly used as a symbol of the eschatological resurrection of the dead. By an argument “from the lesser to the greater,” “if the grain of wheat, which is buried naked, sprouts forth in many robes, how much more so the righteous, who are buried in their raiment” (b. Sanh. 90b).397

HEADS OF WHEAT IN A FIELD

KERNELS OF WHEAT

The man who loves his life will lose it, while the man who hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life (12:25). The love/hate contrast reflects Semitic idiom, pointing to preference rather than actual hatred.398 The present statement is couched in Hebrew parallelism, taking the form of a mashal with two antithetical lines. Such wisdom sayings use paradox or hyperbole to teach a given truth in as sharp terms as possible (cf. b. Taʿan. 22a).

The paradox enunciated here has particular applicability if judged as Christ’s verdict on Greco-Roman ideals of life. For the Greeks, the goal of human existence was bound up with self-fulfillment and the attainment of personal maturity. Following Christ, however, involves sacrifice of oneself and one’s own interests, a truth seen supremely in Jesus’ cross.

Whoever serves me must follow me; and where I am, my servant also will be (12:26). This teaching coheres closely with teacher-disciple relationships in first-century Palestine. “Being a disciple required personal attachment to the teacher, because the disciple learned not merely from his teacher’s words but much more from his practical observance of the Law. Thus the phrase ‘to come after someone’ is tantamount to ‘being someone’s disciple.”399 What is more, the truth enunciated here extends beyond a disciple’s earthly life to his eternal destiny (7:34, 36; 14:3; 17:24).

Father, glorify your name! (12:28). The glory of God as the ultimate goal of his salvific actions is a theme pervading the Old Testament.400

A voice came from heaven (12:28). This is one of only three instances during Jesus’ earthly ministry when a heavenly voice attests to his identity.401 The rabbis called this voice bat qol (lit., “daughter of a voice”). Since it was commonly believed that the prophetic office had ceased and would not be renewed until the onset of the messianic age, the bat qol was the most that could be expected in the interim: “Since the death of the last prophets, Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi, the Holy Spirit [of prophetic inspiration] departed from Israel; yet they were still able to avail themselves of the bat qol” (b. Sanh. 11a; cf. t. Soṭah 13:3).402

A later rabbinic passage illustrates this belief: “One would hear not the sound which proceeded from heaven, but another sound proceeded from this sound; as when a man strikes a powerful blow and a second sound is heard, which proceeds from it in the distance. Such a sound would one hear; hence it was called ‘Daughter of the voice’ ” (Tosafot on b. Sanh. 11a).403 The all-important difference between the New Testament instances of the heavenly voice and the rabbinic notion of the bat qol is that while the rabbis thought of the divine voice as a mere echo, the heavenly voice attesting Jesus is the voice of God himself.

It had thundered (12:29). Thunder was considered to speak of the power and awesomeness of God (1 Sam. 12:18; 2 Sam. 22:14; Job 37:5). It was part of the theophany at Mount Sinai (Ex. 19:16, 19). God’s intervention on behalf of his people is portrayed like a fierce thunderstorm sweeping down on his enemies (Ps. 18:7–15). In such instances, the power of the Creator is tied to that of Israel’s Redeemer (Ex. 9:28; 1 Sam. 7:10; Ps. 29:3; cf. Sir. 46:16–17). The manifestations of God’s power also highlight the contrast between his omnipotence and the idols’ powerlessness (Jer. 10:13 = 51:16).

In New Testament times, light and sound accompanied the manifestation of the risen Christ to Saul (Acts 9:7; 22:9). In the Apocalypse, peals of thunder are shown to emanate from God’s throne (Rev. 4:5; 8:5; 11:19; 16:18; cf. 2 Esd. 6:17). The Sibylline Oracles speak of a “heavenly crash of thunder, the voice of God” (Sib. Or. 5:344–45). The notion of heaven answering human speech in thunder is also found in the ancient Greek world. Thus in Homer’s classic work, Odysseus’s prayer is followed by divine thunder: “So he spoke in prayer, and Zeus the counselor heard him. Straightway he thundered from gleaming Olympus” (Odyssey 20.97–104).404

Others said an angel had spoken to him (12:29). In Old Testament times, angels (or the angel of the Lord) spoke to Hagar (Gen. 21:17), Abraham (22:11), Moses (cf. Acts 7:38), and Daniel (Dan. 10:4–11). In the New Testament, angels are said to minister to Jesus (Matt. 4:11; Luke 22:43; cf. Matt. 26:53), and at one point it was surmised that Paul, too, may have heard an angelic voice (Acts 23:9). Angelic voices are commonplace in the book of Revelation (Rev. 4:1; 5:2; 6:1; etc.).

Now the prince of this world will be driven out (12:31). “Prince” is literally “ruler” (archōn). Similar terminology is also found in Paul’s writings (2 Cor. 4:4; 6:15; Eph. 2:2; 6:12). There are several Jewish (though no rabbinic) parallels to the phrase “prince of the world” with reference to Satan.405 The title “prince of this world” occurs in relation to Beliar in the Ascension of Isaiah (1:3; 10:29; cf. 2:4). In Jubilees, “Mastema” is called “chief of the spirits” or simply “prince” (10:8; 11:5, 11; etc.). More generally, the Qumran texts contain the notion that the “dominion of Belial” extends to his entire “lot.”406 However, unlike extensive intertestamental speculation regarding the demonic supernatural, John is much more restrained, limiting his treatment of Satan exclusively to his role in the plot against Jesus leading to the latter’s crucifixion. See comments also on John 14:30; 16:11; also Luke 10:18.

Will draw all men to myself (12:32). “All men” is generic, “all people.” This does not imply universalism (the ultimate salvation of all; see comments on 1:9). Rather, the approach of Gentiles prompts Jesus’ statement that after his glorification he will draw “all kinds of people,” even Gentiles, to himself (cf. 10:16; 11:52).

The Law (12:34). “The Law” may refer to the Hebrew Scriptures in their entirety rather than merely to the five books of Moses (cf. 10:34; 15:25).

ROMAN CROSS

A model of a typical Roman cross with a nameplate on the top and two wooden beams for the arms and legs.

The Christ will remain forever (12:34). Palestinian Judaism in Jesus’ day generally thought of the Messiah as triumphant, and frequently also as eternal. Such expectations were rooted in the Son of David, of whom it was said that God would “establish the throne of his kingdom forever” (2 Sam. 7:13; cf. John 12:16). This prospect was nurtured both in the Psalms (e.g., Ps. 61:6–7; 89:3–4, 35–37) and prophetic literature (Isa. 9:7; Ezek. 37:25; cf. Dan. 7:13–14). It was also affirmed in intertestamental Jewish writings (Pss. Sol. 17:4; Sib. Or. 3:49–50; 1 En. 62:14) and at the outset of Luke’s Gospel (Luke 1:33).

Perhaps the closest parallel to the present passage is Psalm 89:37, where David’s seed is said to “remain forever” (LXX: menei eis ton aiōna). Notably, this psalm is interpreted messianically both in the New Testament (Acts 13:22; Rev. 1:5) and rabbinic sources (Gen. Rab. 97, linking Gen. 49:10; 2 Sam. 7:16; Ps. 89:29). But probably Jesus refers not so much to any one passage but to the general thrust of Old Testament messianic teaching. Elsewhere in John, people express the expectation of a Davidic Messiah born at Bethlehem (John 7:42) and of a hidden Messiah to be revealed at the proper time (7:27; cf. 1:26).

The Christ … the Son of Man (12:34). It is unclear whether Palestinian Jews in Jesus’ day, whose concept of Messiah was bound up largely with the expectation of the Davidic king, also linked the Coming One with the apocalyptic figure of the Son of Man (cf. Dan. 7:13–14).407

Walk while you have the light, before darkness overtakes you. The man who walks in the dark does not know where he is going. Put your trust in the light (12:35–36). The term “walk” (peripateō) frequently occurs in John’s Gospel in a figurative sense in conjunction with light and darkness.408 Similar terminology can be found in the Qumran literature: “the sons of justice … walk on paths of light,” while “the sons of deceit … walk on paths of darkness” (1QS 3:20–21; cf. 4:11). The notion of “walking in the light” or “in darkness” in John resembles the thought in the Scrolls that there are two ways in which people may walk, light and darkness. Both John and the Scrolls hark back independently to Old Testament terminology, especially Isaiah: “Let him who walks in the dark, who has no light, trust in the name of the LORD” (Isa. 50:10); “the people walking in darkness have seen a great light” (9:2, quoted in Matt. 4:16). The important difference between John and the Scrolls is that the former calls people to “put their trust in the light,” while the latter assume that the members of the community are already “sons of light.”

Sons of light (12:36). “Son of …” reflects Hebrew idiom; the expression “sons of light,” however, is not attested in rabbinic literature. A “son of light” displays the moral qualities of “light” and has become a follower of the “light” (cf. Luke 16:8; 1 Thess. 5:5; Eph. 5:8). The phrase is also common in the Dead Sea Scrolls, where it designates members of the Qumran community.409 “Born of light” occurs in 1 Enoch (108:11; cf. also T. Naph. 2:10: “so you are unable to perform the works of light while you are in darkness”).

MENORAH

Fragments of plaster found in a Herodian-era house discovered in Jerusalem. This is the earliest depiction of the candelabrum, which stood in the temple.

The Jews Continue in their Unbelief (12:37–50)

Even after Jesus had done all these miraculous signs in their presence, they still would not believe in him (12:37). The Jews’ failure to believe in Jesus’ day is reminiscent of the unbelief of the desert generation, which had witnessed God’s mighty acts of power (displayed through Moses) at the Exodus (Deut. 29:2–4). No greater sign than the raising of Lazarus—the seventh, climactic sign in John—could be given.

This was to fulfill the word of Isaiah the prophet (12:38). This leads off a whole series of fulfillment quotations in John’s Gospel, stressing the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy in the events of Jesus’ life, especially the events surrounding his crucifixion.410

Lord, who has believed our message and to whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed? (12:38). The reference cited is Isaiah 53:1 (LXX; cf. Rom. 10:16). In the original context, Isaiah’ message pertains to the Servant of the Lord, who was rejected by the people but exalted by God (cf. Isa. 52:13–15). In John’s Gospel, the passage is applied to Jesus the Messiah, who is that promised Servant, and to the rejection of his message and his miraculous signs (“arm of the Lord”) by the Jewish people. Thus Jewish rejection of God’s words is nothing new; as Isaiah’s message had been rejected, so is Jesus’. The phrase “arm of the LORD” serves in the Old Testament frequently as a figurative expression for God’s power.411

He has blinded their eyes and deadened their hearts, so they can neither see with their eyes, nor understand with their hearts, nor turn—and I would heal them (12:40). The reference cited is Isaiah 6:10 (here closer to the Hebrew than to the LXX). The Hebrew original moves from heart to ears to eyes and then back from sight to hearing to understanding. John does not refer to hearing but focuses instead on sight, probably owing to his mention of Jesus’ miraculous signs in John 12:37. The Jews considered the heart to be the seat of mental as well as physical life (cf. Mark 8:17–21 par.).

Isaiah … saw Jesus’ glory (12:41). In light of the preceding quotation of Isaiah 6:10, the background to the present statement is probably the call narrative in Isaiah 6. This is confirmed by the Targums (Aramaic paraphrases of the Old Testament). One Targum of Isaiah 6:1 changes “I saw the LORD” to “I saw the glory of the LORD,” and changes “the King, the LORD Almighty” in Isaiah 6:5 to “the glory of the shekinah of the eternal King, the LORD of hosts” (Tg. Ps.-J., 1st cent. B.C.–3d cent. A.D.). The notion of a preexistent Christ who was present and active in the history of Israel appears elsewhere in the New Testament (cf. 1 Cor. 10:4; see also Philo, Dreams 1.229–30). Later interpreters speculated that the prophet looked into the future and saw the life and glory of Jesus (Ascen. Isa. [2d cent. A.D.]).

But because of the Pharisees … for fear they would be put out of the synagogue (12:42). See comments on 9:22.

He does not believe in me only, but in the one who sent me (12:44). See comments on 5:23. The entire closing section (12:44–50) presupposes Jewish teaching on representation, according to which the emissary represents the one who sends him (cf. m. Ber. 5:5).412

That very word which I spoke will condemn him at the last day (12:48). Verses 48–50 echo the book of Deuteronomy (cf. 18:19; 31:19, 26).413 There it is God who takes vengeance on the man who refuses to hear; in the Targums, it is God’s memra or word. “And the man who does not listen to his words which he [the future prophet] will speak in the name of my memra, I in my memra will be avenged of him” (Tg. Neof. on Deut. 18:19); “my memra will take revenge on him” (Tg. Ps.-J. on Deut. 18:19).

Sometimes in intertestamental Jewish literature, the Law seems to take a more active part in the process of judging: “And concerning all of those [the sinners], their end will put them to shame, and your Law which they transgressed will repay them on your day” (2 Bar. 48:47); “and he will destroy them without effort by the law (which was symbolized by the fire)” (4 Ezra 13:38). In Wisdom of Solomon 9:3, wisdom is described as an assessor with God in judgment (cf. Philo, Moses 2.53).

I know that his command leads to eternal life (12:50). According to the book of Deuteronomy, God’s commandments provide the framework within which Israel is to fulfill her calling as a people set apart for God (e.g., Deut. 8:3; 32:46–47). Jews commonly saw the law of Moses as the source of life (32:45–47; cf. John 5:39). The problem, however, is that no one keeps the law perfectly or is able to do so.