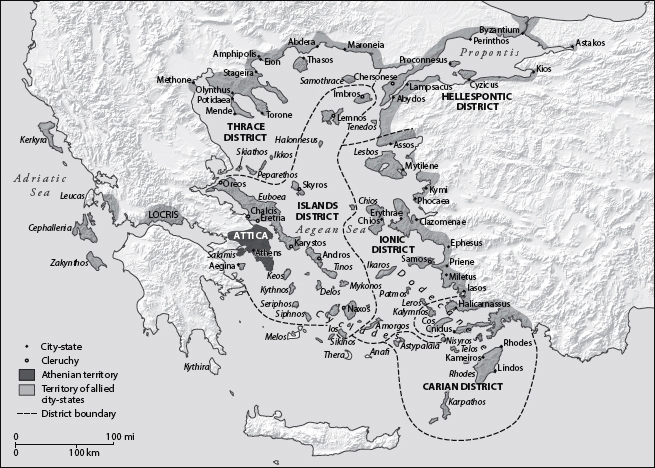

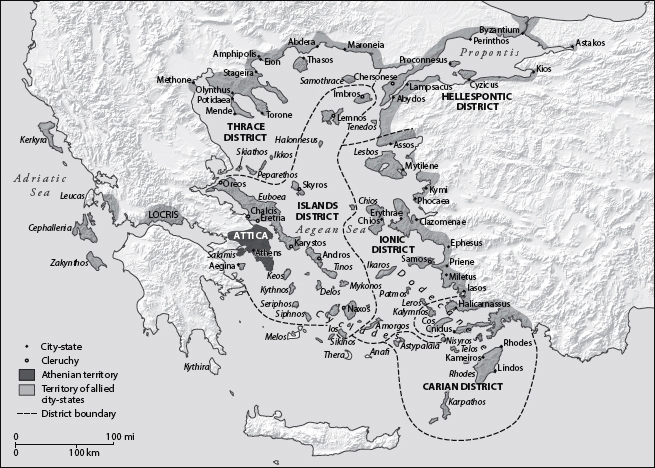

FIGURE 2. Map of the Athenian Empire ca. 431 B.C.

Pericles and Athenian Imperialism

The power of Pericles, founded on speech as much as on action, developed within the framework of an Athenian city that, from 450 onward, was caught up in a rapid process of democratization. Yet the increasing liberty of the dēmos was accompanied by the enslavement of its allies within the framework of the Delian League. This league, founded in 478 B.C., progressively became an instrument in the service of Athens. The democratization of the city progressed at the same rate as its increasing power over its allies.

What exactly was the role that Pericles played in the establishment of Athenian imperialism? Did he try to check the imperial dynamic or did he, on the contrary, act as its catalyst? And, anyway, is it possible to speak already of Athenian imperialism at the time when the stratēgos was exercising a decisive influence on the destiny of the city? Today historians are still arguing about these questions. Some represent Pericles’ “reign” as the pivotal moment in the construction of Athenian imperialism, while other scholars, on the contrary, endeavor to exonerate the stratēgos from all responsibility in this matter, either by emphasizing his personal moderation or by maintaining that the cusp of imperialism was reached only after his death.

However, it will not do to look no further than that alternative. The stratēgos was swept up in a dynamic that, both upstream and downstream, shaped far more than his own individual actions, for it had already involved what was, broadly speaking, a policy embraced by Cimon and it would affect Cleon’s rise to power. Pericles was simply continuing an imperialist system that was initiated before him and that went on after him, a system that was backed by a general consensus both among the Athenian elite and also more widely in the city of Athens.

Pericles took part in running the empire with no misgivings at all. His military exploits in Euboea, Samos, and Aegina were all against rebellions that he simply crushed with a considerable degree of bloody force. If there was any specifically Periclean aspect to the situation, it lay not in imperial practices but rather in what he said about them. Pericles was probably the first to theorize the need for Athenian imperialism and publicly display the city’s domination over the league allies by organizing the construction of the Odeon and the Parthenon.

PERICLES AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE ATHENIAN EMPIRE

The Delian League: From Summakhia to Arkhē

In 478 B.C., at the end of the Second Persian War, the Athenians, with the cooperation of a large number of the cities dotted around the Aegean, founded a league (a summakhia), the seat of which was the small and sacred island of Delos. According to Thucydides (1.95.1), membership was at that time voluntary. The cities spontaneously chose to unite their forces under the leadership of Athens, in order to prevent the Persians returning to the Aegean. To this end, members had to contribute to the war effort in proportion to their resources, either directly, with ships and soldiers, or indirectly, by paying tribute (phoros) representing the monetary equivalent of the ships to be supplied (Thucydides, 1.98.3). The overwhelming majority of the cities chose the second option: as far as we can tell from the stēlē on which the contributions of the league’s member cities were recorded in 454, only thirteen or fourteen of the contributing cities were still paying tribute in the form of triremes or military contingents. In short, Athens did the fighting, while the allies paid.

Also according to Thucydides, the total sum of tribute was fixed at 460 talents in 478 by the Athenian Aristides. In order to calculate the contributions of each of the cities, Aristides no doubt took over the framework of the Achaemenid system of taxation that was set in place after the revolt of Ionia in 493: to a certain extent, the allies had simply switched masters. However, at this juncture, the members of the alliance were still deciding on its general policies all together, with each contributor possessing a vote in the league’s council (sunedrion).

A number of crucial dates mark out the Delian League’s development and its slide into imperialism. First there was the battle of Eurymedon, fought between 469 and 466 B.C. by the Athenian fleet, commanded by the stratēgos Cimon. This great victory de facto sealed the end of the Persian threat in the Aegean. Next came the peace negotiated by Callias between the Athenians and the Persians in 449 B.C. Following the failure of the Athenian expedition to Egypt, the Athenians sent Callias as an ambassador to Susa, where a peace treaty was signed, with the Persians agreeing to leave the Aegean and the cities of Asia Minor under the control of the Athenians, while the Athenians, for their part, undertook not to launch any more expeditions against the royal territories. The peace of Callias thus, de facto, if not de iure, put an end to the Persian threat.1

After the peace had been signed, the Delian League no longer had as much raison d’être, and that is perhaps why the levying of tribute was suspended in 448 B.C.2 However, that respite was short-lived, and the Athenians then continued to receive a phoros even though the Persian threat had disappeared. These taxes were resented all the more because in the late 450s the league’s treasury had been transferred to Athens. The sum to be paid as tribute was fixed every four years by the Athenian ekklēsia, which summoned all the allies at the time of the great Panathenaea, in order to reveal to them the sum that they were to pay annually. All of this is attested by Cleinias’s decree.3

It was therefore certainly not by chance that several major revolts broke out within this league that now had no purpose. In 447/6 Euboea revolted against Athens, which, after putting down the uprising, imposed democratic systems on the island and installed cleruchies, garrisons of Athenian soldiers, who settled there.4 It was at this point that the city of Histiaea became the cleruchy of Oreos. In 440/39, the island of Samos was pacified after a long siege, as was then the city of Byzantium. The vocabulary used to speak of the league and its members now changed: the Athenians spoke no longer of their hēgemonia but of their arkhē—their domination—and they now referred to the league members as hupēkooi, dependents, not allies.5 During the Peloponnesian War, the revolts multiplied, prompting the Athenians to exact heavy reprisals. In 427, Mytilene was forced back into the league and the island of Lesbos was subjected to heavy repression. In 425, tribute was almost tripled in order to cope with the heavy expenses of warfare. Athenian imperialism had now reached its peak. It was not until the disastrous result of the Sicilian expedition (415–413 B.C.) and, above all, the last years of the war that Athens’s grip loosened; the league was finally dissolved at the end of the conflict, in 404 B.C.

Did Pericles play a role in the imperial metamorphosis of the Delian League? Did he, as leader of the people, act as a catalyst in the aggressive tendencies of the Athenians or did he, on the contrary, try to keep them in check? In order to resolve that alternative, we must first determine a crucial question: exactly when was the league transformed into an empire (figure 2)?

The Slide into Imperialism: A Periclean Turning Point?

Precisely when did Athens increase its power over the members of the Delian League to the point of turning them into mere subjects, or even “slaves”? Among historians, this tricky question eludes a consensus. Specialists on the Athenian Empire disagree on the dating of the complex epigraphical evidence. A number of decrees testifying to the growing imperialism of Athens have been found, but it has not been possible to date them precisely, on account of their lamentable state of preservation. While most epigraphists place the date of their engraving between 450 and 440, some specialists defend a later dating, around 430/420.6 One might remain unmoved by this erudite battle were it not for the fact that what is at stake here is crucial for an understanding of the nature of the Periclean empire and the role that Pericles himself played in its development. There are two possibilities: if these inscriptions go back to the mid-fifth century, the hardening of Athenian imperialism must have taken place under Pericles and probably at his instigation; if, on the contrary, they were not engraved until the time of the Peloponnesian War, “only the war forced the Athenians to tighten their grip on the Aegean world,”7 so Pericles, who died at the beginning of the conflict, was in no way implicated in the process.8

To be quite frank, the second alternative does not seem credible. Whatever the date of the decrees in question, there is plenty of other evidence of the Athenian descent into imperialism as early as the middle of the fifth century. On this basis, it might seem logical to detect signs of specifically Periclean policies, particularly since some authors who were contemporaries of the stratēgos make this their justification for taking a hard line in this matter. One such is Stesimbrotus of Thasos, a native of an island placed under Athenian control, who certainly criticizes Pericles for his cruel behavior toward the people of Thasos and contrasts this to the supposed moderation of Cimon.9 In reality, that contrast does not withstand scrutiny. What strikes one upon reading the sources that are available is above all how quickly the Delian League was transformed into an empire placed at the service of Athens. In fact, this happened as early as the time when Cimon dominated the political life of the city. So it was probably under his leadership that the first of the allies’ revolts was repressed. As early as 475, the city of Carystus, in Euboea, was forced, against its will, to join the league. In 470 or 468, Naxos revolted, and, as Thucydides declares, “this was the first allied city to be enslaved [edoulōthē] in violation of the established rule” (1.98.4). However, the first rebellion of any magnitude was that of Thasos, between 465 and 463. It took the Athenians two years to overcome this city that possessed, on the continent, mineral resources and forests that were eminently desirable.10 When the conflict was over, the city precinct was razed to the ground and its navy was confiscated. The people of Thasos became tribute-payers to Athens and lost their liberty. Very soon, the Athenians also insisted that the cities that had revolted, once they rejoined the alliance, should solemnly swear never again to secede, as we know from an inscription in Erythrae, a city in Asia Minor that rejoined the league some time between 465 and 450 B.C.11

FIGURE 2. Map of the Athenian Empire ca. 431 B.C.

An aggressive imperialist thrust was thus initiated as early as the second third of the fifth century. No Athenian leader could afford to resist it if he wished for the support of the people. In this context, Cimon repressed the revolts of the allies as regularly as did Pericles after him. It was Cimon who was in charge of the lengthy siege of Thasos in 465–463 and also he who decisively promoted the development of cleruchies, the Athenian garrisons that were installed in allied territories.12 Apart from a few minor disagreements, the political leaders clearly shared in common the conviction that the empire constituted the guarantee of Athenian sociopolitical stability. There may have been disagreement about the methods to be adopted, but there was none where the principle was concerned: the empire was vital for Athens, so, if necessary, the allies had to be repressed by force. Moreover, the transfer of the Delian League’s treasury, often interpreted as the ultimate symbol of the hardening attitude of imperialism, may quite possibly have taken place before 454—the date when it is actually mentioned—indeed, it may have been carried out even prior to the victory of Eurymedon, at the beginning of the 460s.13

All the same, it would be exaggerated to detect no change at all in Athenian politics during the years between 440 and 430. However, such developments probably owed nothing to Pericles himself but everything to the transformation of the geopolitical context and, in particular, the establishment of peace, de facto if not de iure, with Persia. With the signing of the peace of Callias in 449, Athenian domination in effect became radically illegitimate in the eyes of the allies/subjects: the league was now subject to a whole spate of revolts, which were countered by increasing repression.

Faced with mounting challenges, Pericles unhesitatingly resorted to force and was, as a result, sometimes accused of cruelty. This practical experience of his, marked by a series of bloody incidents, now led him, at the theoretical level, to develop his lucid thinking about the empire and the need to maintain it.

PERICLES FACED BY THE ALLIES: IMPERIAL PRACTICES AND REPRESENTATIONS

The Recourse to Force: Periclean Cruelty

Still today, certain historians seek to palliate the image of Pericles’ actions in the face of the allies. Donald Kagan, in his biography, emphasizes the relative moderation of the stratēgos’s behavior in this episode.14 “Save Private Pericles!”: the stratēgos cannot possibly have been cruel and risk besmirching the Greek miracle with an indelible stain! That is an eminently ideological attitude and it should be analyzed in relation to the biographer’s own political background. In this respect, his political trajectory is instructive: having started out as a liberal—in the American sense of the term—Kagan became a Republican in the 1970s and then, in the 1990s, was one of the founders of a neo-conservative “think tank” (“Project for the New American Century”). Meanwhile, one of his sons became John McCain’s advisor on foreign policy. So it is perfectly logical that, as an apostle of American interventionism abroad, Kagan should present us with a Pericles who is both firm yet temperate and is the epitome of moderation when faced with undisciplined and recalcitrant allies.15

However, that supposed moderation is a fiction. During the years in which he played a leading role, Pericles made sure that the allies’ revolts were shamelessly repressed, sometimes even with cruelty. In truth, the stratēgos was intimately associated with the repressive policies of Athens. Significantly enough, Thucydides, who only mentions Pericles three times in his long account of the pentēkontaetia (the period of almost fifty years [478–431] that separated the end of the Persian Wars from the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War) twice mentions his direct involvement in forcing the allies to toe the line.

The Euboean Revolt

First, the historian describes his participation in the punishment of Euboea, in 446 B.C.: “The Athenians again crossed over into Euboea under the command of Pericles and subdued the whole of it; the rest of the island they settled by agreement, but expelled the Histiaeans from their homes and themselves occupied their territory.”16 That was how Pericles wreaked his revenge on those who, having captured an Athenian vessel, massacred the entire crew.17 The city was turned into a cleruchy and the rest of the Euboean cities were placed under strict supervision, as is attested epigraphically by two decrees concerning Eretria and Chalcis.18

The comic poets dwelt upon this bloody episode—in particular, in Aristophanes’ Clouds, a play that was staged for the first time in 423 B.C. Referring to Euboea, the poet has one of the characters say: “We have stretched it enough, we and Pericles!”19 The treatment meted out to the rebels was so traumatic that it was still haunting the Athenian conscience nearly forty years later. When the Peloponnesian War ended, at the news of the defeat at Aigos Potamoi, in 405, the Athenians were gripped by terror, fearing now to see the allies, so long tyrannized, seeking revenge for the exactions that they had suffered. And in the long list of outrages, the crushing of the Euboean revolt figured prominently: “That night, no one slept, all mourning, not for the lost alone, but far more for their own selves, thinking that they would suffer such treatment as they had visited upon the Melians, colonists of the Lacedaemonians, after reducing them by siege, and upon the Histiaeans and Scionaeans and Toronaeans and Aeginetans and many other Greek peoples” (Xenophon, Hellenica, 2.2.3). The repression of Euboea in 446, led by Pericles, thus symbolized all the harshness of Athenian imperialism, to the point of leaving an indelible mark on the civic conscience.

The Samos Affair

Pericles’ second intervention left just as deep a scar. In 440–439 B.C.,20 taking advantage of an altercation between Samos and Miletus over the possession of Priene, in Asia Minor, the Athenians embarked on a long war against the Samians, who had defected and left the Delian League. We need not dwell on the ins-and-outs of the conflict but should note that this war turned out to be extremely costly for Athens, both in men and in money. In money, first: an inscription records the total sum of the expenses for the war. The final sum was as high as 1,400 talents, more than three years’ accumulated tribute, which was later paid back solely by the Samians!21 But the war was also costly in men and was marked by an extreme violence that struck the imagination of ancient authors. Two stories focus on the cruelty of the conflict; it was a violence that was initially reciprocal but for which, later on, the Athenians alone were held responsible.

The first episode was recorded in the fourth century by Douris of Samos, who was well placed to know of the affair since he was a native of the rebel island.22 In the course of the conflict, some Athenian prisoners were captured by the Samian rebels, who tattooed their faces with an owl. Gratuitous cruelty? Not at all. The rebels were simply paying back the Athenians who, earlier, had marked the faces of enemy prisoners with the prow of a Samian ship, the Samaina.23 By recording this incident, Douris clearly intended to underline the Athenians’ initial responsibility in this unleashing of violence. However, the episode took on another, less immediate significance. By tattooing their prisoners in this way, both groups of belligerents turned them into monetary symbols and consequently into interchangeable merchandise—for, just as the owl was the monetary symbol of Athens, the Samaina was that of Samos (figure 3).24

Furthermore, this story may reveal the true cause of this bloody conflict. Over and above the reasons alleged by the ancient sources, the main objective of the repression led by Pericles may have been to impose upon Samos the use of Athenian coins. The Samians appear to have refused to apply Clearchus’s decree, which was probably passed in the early 440s and imposed upon all the allies the use of Athenian weights and measures and silver currency.

FIGURE 3. A coin war: (a) Athenian silver tetradrachm, minted 449 B.C. 17.07 grams. Owl facing right. SNG Copenhagen 31. Photo © Marie-Lan Nguyen. (b) Silver tetradrachm, minted in Zancle (Messana) by the Samians between 493 and 489 B.C., showing, on the reverse, the prow of a Samian ship (Samaina). Image © Hirmer Fotoarchiv.

However that may be, the Samos affair shows us a Pericles who resorted to unbridled violence, as the outcome of the conflict testifies. After the Athenians’ victory, the Samians “were reduced by siege and agreed to a capitulation, pulling down their walls, giving hostages and consenting to pay back by instalments the money spent upon the siege” (Thucydides 1.117.3). All this was altogether normal; Athens applied victors’ rights and deprived the Samians of all attributes of sovereign power: its ramparts, its fleet, and its currency. What was less normal though was the cruelty that, again according to Douris of Samos, Pericles inflicted upon the Samian elite: “To these details, Douris the Samian adds stuff for tragedy, accusing the Athenians and Pericles of great cruelty. But he appears not to speak the truth when he says that Pericles had the Samian trierarchs and marines brought into the marketplace of Miletus and crucified there, and that then, when they had already suffered grievously for ten days, he gave orders to break their heads in with clubs and make an end of them, and then cast their bodies forth without funeral rites.”25 In Douris’s version, the horror of the tortures—inflicted in Miletus, not in Athens—had been intended to serve as a lesson addressed to the entire empire. But this account aimed above all to emphasize not only the cruelty of Pericles, but his impiety: to deprive bodies of the funeral rites was a grave transgression, the full implications of which are revealed in Sophocles’ Antigone. It may be that Douris is overdramatizing (epitragoidein) the events, as Plutarch, being concerned to protect the reputation of the Athenian stratēgos, claims; but in any case, Douris’s testimony underlines the existence of a tradition hostile to Pericles that deliberately emphasizes his intolerable cruelty.26

In fact, such a sinister reputation already surrounded Pericles’ father, Xanthippus. Right at the end of the Histories, at a strategic point in his text, Herodotus produces an equivocal image of Pericles’ father: guided by vengeance, Xanthippus had the Persian governor Artaÿctes crucified at Sestos, after having his son stoned to death before his eyes.27 Perhaps this was a way for the historian, himself a native of Halicarnassus, implicitly to cast blame upon the actions of the son by means of an account of his father’s behavior. Herodotus presented Xanthippus as the initiator of a strategy of terror that reached its zenith under Pericles.28

Such cruelty was further amplified with the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War in 431, as is shown by the expulsion of the Aeginetans in the first year of the conflict. Here too, it was probably Pericles who initiated that repression.

The Expulsion of the Aeginetans

Within a context of exacerbated tensions, the stratēgos decided to punish the Aeginetans even though they had not, in fact, revolted against Athens. That, at least, is the version favored by Plutarch: “By way of soothing the multitude who … were distressed over the war, he won their favor by distributions of moneys and proposed allotments (kai klēroukhias egraphen) of conquered lands; the Aeginetans, for instance, he drove out entirely and parcelled out their island among the Athenians by lot.”29 There were, in truth, several reasons why Aegina was punished in this way. In the first place, it had always been an undisciplined ally that had been late in joining the league (in around 459 B.C.), and it was, furthermore an ancient naval power that was a longstanding rival of the Athenians.30 Second, the Athenians accused the Aeginetans of having provoked the war and encouraged the Spartans’ hatred of Athens (Thucydides, 2.27.1); and last, the Athenians were in need of a sure base for themselves, within reach of the Peloponnese.

Although Thucydides does not accuse Pericles directly, there can be no doubt that he was implicated in this business. One of the only statements actually attributed to Pericles—for he left no writings of his own—refers precisely to the fate of the island, “urging the removal of Aegina as ‘the eye-sore of the Piraeus,’”31 and evoking the sticky substance that gathers on the lids of an infected eye. In this way, Pericles assimilated the island of Aegina to a bodily secretion that the Athenians were invited to suppress by means of an appropriate treatment. The metaphorical scorn reflected the real violence to which the Aeginetans were subjected at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War.

Pericles’ career, from the Euboean affair in 446 down to the expulsion of the Aeginetans, definitely suggests an unchanging attitude toward the allies. However, in this respect, the stratēgos was no better and no worse than anyone else and was by no means original. He was simply continuing a policy that was initiated before him—pace the admirers of Cimon such as Ion of Chios and Stesimbrotus of Thasos—a policy that was also continued after him, whatever the critics of Cleon, such as Thucydides, have to say.32 But what distinguished Pericles was the lucidity that he acquired from this experience of warfare punctuated by brutal episodes. The stratēgos developed a deep line of thought on the empire and the necessity of maintaining it. It was a choice that he theorized in words and materialized in grandiose monuments.

The Spectacle of Force and Pericles’ Presentation of It

The Theorization of Imperialism: A Necessary Injustice

If there is one original aspect to Pericles’ attitude to imperialism, it lies not so much in his practice as in the way that he represented the empire both to others and to himself. In the speech that he made in 430, faced with the anger of the Athenian people, the stratēgos set out a particularly lucid analysis of the Delian League and the way that it worked:

You may reasonably be expected, moreover, to support the dignity which the city has attained through empire—a dignity in which you all take pride—and not to avoid its burdens, unless you resign its honours also. Nor must you think that you are fighting for the simple issue of slavery or freedom; on the contrary, loss of empire is also involved and danger from the hatred incurred in your sway. From this empire, however, it is too late for you ever to withdraw, if any one at the present crisis, through fear and shrinking from action does indeed seek thus to play the honest man; for by this time the empire you hold is like a tyranny, which it may seem wrong to have assumed, but which, certainly, it is dangerous to let go. Men like these would soon ruin a city if they should win others to their views, or if they should settle in some other land and have an independent city all to themselves (Thucydides, 2.63.1–3).

The stratēgos conceded that it was perhaps unjust to change the Delian League into an empire at the service of Athens. However, there could be no question of reversing the decision, for to do so would be to accept slavery, douleia.33 His reasoning is subtle: it is necessary to defend an empire, even one that is acquired by coercion, for it would be too dangerous to give it up. If the allies cease to be in thrall to Athens, they will not remain neutral but will switch over to the enemy in order to wreak vengeance for the tribulations that they have suffered. In his speech, Pericles, rather then retreating on the subject of imperialism, goes into the attack. However unjust it was, the people must continue to act tyrannically toward the members of the League.34 There can be no question of dismounting once one’s steed is already charging.

Convinced of the necessity of the empire, Pericles furthermore undertook to lend legitimacy to the power of Athens by means of monuments that, over and above their proclaimed purpose, gave material expression to the city’s new imperial status.

The Odeon and Xerxes’ Tent: From One Empire to Another

The Odeon, constructed between 446 and 430 B.C., was associated so closely with Pericles that Cratinus, the comic poet, had one of his characters declare: “The squill-head Zeus! Lo! Here he comes, the Odeon like a cap upon his cranium, now that for good and all the ostracism is o’er.”35 The Odeon as headgear: what better way of expressing the link that bound the monument and the stratēgos together?

Today, this building is little known, for the archaeological excavations were never completed. But in Antiquity, it was considered one of the most impressive monuments in a city that was rich in architectural marvels (figure 4). The precinct in which it stood could accommodate huge crowds: this Odeon, flanking the theater of Dionysus, which was at that time built of wood, appeared as an immense hypostyle construction—with multiple colonnades—of 4,000 square meters in area (around 43,000 square feet). It was the largest public building in Athens and the first theater in Antiquity ever provided with a roof.

FIGURE 4. The Odeon of Pericles (ca. 443–435 B.C.): a virtual reconstruction. Image © the University of Warwick. Created by the THEATRON Consortium.

At an architectural level, the Odeon was freely inspired by Xerxes’ tent, which had been brought back to Athens, as booty, after the victory at Plataea, which the Greeks won over the Persians in 479 B.C.36 According to Plutarch: “The Odeon, which was arranged internally with many tiers of seats and many pillars, and which had a roof made with a circular slope from a single peak, they say was an exact reproduction of the Great King’s pavilion, and this too was built under the superintendence of Pericles” (Pericles, 13.5). One should, incidentally, not be misled by the vocabulary, Xerxes’ “pavilion” or “tent” resembled a real palace that could be dismantled and transported elsewhere and that adopted the form of the imperial residences of Persepolis. Its true model was the Apadana and the palace of a hundred columns, a reception hall built by Xerxes himself.37 In adopting such an architectural style, Pericles was modeling his Odeon on the great imperial architecture of the Achaemenids.

This strange mimicry had two symmetrical functions. It was intended, within the urban setting of the city itself, to commemorate the Athenian victory in the Persian Wars. Better still, by creating this hall for spectacles, the Athenians were manipulating the despotic symbolism associated with Xerxes’ tent and adapting it to democratic purposes. Whereas the original pavilion had, in principle, been reserved for the exclusive enjoyment of the Great King, the Odeon was conceived as an edifice open to all, constructed for the pleasure of the entire population. However, this architectural choice probably conveyed a quite different message to the foreigners who passed through Athens. The edifice must have struck them as a veritable imperialist manifesto.38 The Odeon, which imitated the splendors of Achaemenid architecture, returned the allies to the status of subjects and reminded them that they had, in truth, simply swapped masters. We should furthermore bear in mind that it was on the staircase leading to the Apadana, the throne-room in Persepolis, on which the Odeon drew freely for inspiration, that the long cohorts of tributary peoples had been represented, bringing their contributions to the Great King, in a lengthy procession (figure 5). Nor was that association solely metaphorical: in Athens, the allies of the Delian League were obliged to pass in front of Pericles’ Odeon when they came to deposit their tribute in the theater of Dionysus.39 This edifice brilliantly symbolized their new status as tribute-bearers, strictly in line with the imperial Achaemenid heritage.40

FIGURE 5. Tribute-bearers (maybe Ionians) from the ceremonial staircase (northern stairway) of the Apadana (Iran: Persepolis, end of the sixth century B.C.). In Persepolis and Ancient Iran with an introduction by Ursula Schneider, Oriental Institute. © 1976 by The University of Chicago. Image courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

The same reasoning may be applied to the city’s most famous monument, the Parthenon, for in many respects this too testified to the hardening of Athenian imperialism.

The Parthenon: A Marble Symbol of Athenian Imperialism

There can be little doubt that the great building program launched in Athens after 450 was associated with imperial dynamics. Pericles’ opponents would even reproach him for having misapplied imperial revenues in order to realize his monumental policy and, especially, to build the Parthenon with its statue of Athena Parthenos: “Hellas is insulted with a dire insult and manifestly subjected to tyranny when she sees that, with her own enforced contributions for the war, we are gilding and bedizening our city, which, for all the world like a wanton woman, adds to her wardrobe precious stones and costly statues and temples worth their millions” (Plutarch, Pericles, 12.2). To be sure, this declaration calls for a measure of qualification. For it is by no means certain that the Parthenon was built with the money obtained from the allies.41 All the same, the fact remains that, in the imaginary representations of the Athenians and of their allies, this building remained closely associated with the onward march of the empire, for was it not used to shelter the league’s treasury, which was transferred to Athens in 454 B.C., at the latest?

It is, moreover, this practical necessity—namely, to find a place for the treasury—that explains the strange layout of the monument. The fact is that, ordinarily, a Greek temple was built in accordance with a stereotyped schema: a vestibule (pronaos), then a central hall containing the cult statue (naos), and, finally, a back room (opisthodomos), for the use of the temple staff. In comparison to this canonical arrangement, the structure of the Parthenon is, to say the least, unusual—and for two reasons: in the first place, the huge dimensions of the naos contrast strongly with the limited area taken up by the pronaos and the opisthodomos (figure 6). The fact was that the central hall had to be spacious enough to house the immense statue of Athena Parthenos. Then, an extra room, with four columns, was set between the naos and the opisthodomos: a hall that gave its name to the edifice as a whole, the Parthenon, “the room for the virgin.”42 It was in this space that the city treasures were stored, in particular the treasury of the Delian League. This extra room that housed the allies’ tribute was thus the very symbol of Athenian imperialism. It is surely not merely by chance that the four columns that supported the roofing of this room were in the Ionic style. Incorporating this Ionic style at the very heart of a Doric edifice was a way for the Athenians to give material expression to their domination over a league made up chiefly of Ionian cities.

FIGURE 6. Athens, Acropolis, the Parthenon (ca. 447–437 B.C.): plan of the temple. Drawing by M. Korres. Courtesy of the Media Center for Art History at Columbia University.

Far from being a temple,43 the Parthenon was a treasury and a monument that glorified imperialism and symbolized the hardening or even petrification of Athenian domination. In this respect, the chronology is significant: the construction of the Parthenon began in 447, one year before the great Euboean revolt, and it was completed in 438, one year after the Samos affair.

In truth, there is nothing specifically Periclean about the management of the empire, except a particular way of theorizing about its necessity, and its presentation. Although we should perhaps not impute to Pericles in particular the responsibility for the city’s slide into imperialism, Pericles certainly did take over this new order without compunction, both in practice and in the representations that he promoted. Now we must evaluate to what degree the imperial dynamic and democratization of the city went hand in hand. Let us do so by analyzing the bases of the Periclean economy.