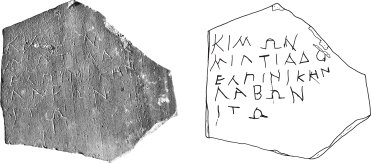

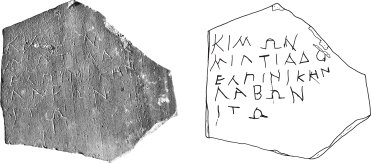

FIGURE 9. Ostraka of Cimon (ca. 462 B.C.). From S. Brenne, 1994, “Ostraka and the Process of Ostrakophoria,” in W.D.E. Coulson et al., eds., The Archaeology of Athens and Attica under Democracy. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books, 13–24, here fig. 3-4, p. 14.

The Individual and Democracy: The Place of the “Great Man”

Now, at the end of this biographical odyssey, let us return, if not to the shores of Ithaca, at least to the question that served as its starting point. Was Pericles an all-powerful figure or an evanescent one? How, exactly, did the actions of the stratēgos and the will of the people interact? Can we settle for the forthright conclusion expressed by Thucydides in his final panegyric for stratēgos: “Athens, though in name a democracy, gradually became in fact a government ruled by its foremost citizen” (2.65.9)? According to the ancient authors, there seemed to be no doubt about it. Pericles’ monarchy, theorized by the historian of the Peloponnesian War, was also a favorite theme of the comic poets, who were always ready to represent the stratēgos as an unscrupulous tyrant. In truth, Pericles’ admirers and detractors were all perfectly happy to agree on one point—namely, the predominance of the stratēgos’s position in the city of Athens. Some—Thucydides for one—depict him as a beneficent sovereign; others, as a dangerous and corrupting tyrant. Either way, the dēmos appears as a mere puppet manipulated by Pericles. Thanks to his establishing the misthos and launching his policy of major building works, the stratēgos is depicted as a monarch showering benefits upon his passive or even apathetic subjects.

Although that view is purveyed on every side by the ancient authors, it needs to be criticized and replaced in context. It fails to take into account the various control-mechanisms that surrounded the power of Athenian magistrates, Pericles first and foremost. Not only did he always have to negotiate with the other stratēgoi, which, de facto, limited his influence, but, like any other member of the elite, he was subject to many forms of supervision on the part of the people. At an institutional level, his authority was frequently the object of scrutiny; accounts had to be submitted, and there was always a real threat of ostracism or of an accusation of high treason. At the social and ritual level, Pericles was forced to withstand numerous attacks from the comic dramatists, justify himself in the face of insistent rumors about his behavior, both private and public, and suffer noisy abuse from the crowds in the Assembly. Although his influence over the city’s destiny was undeniable, the stratēgos was obliged to take popular expectations into account and, accordingly, adopt an attitude in conformity with the democratic ethos. Far from ruling Athens as a monarch, Pericles lived constantly under tension in a context in which the power of the demos was relentlessly increasing.

“PERICLES THE OLYMPIAN”: THE POWER OF A SINGLE MAN?

Monarch and Tyrant

When addressing the Athenians right at the beginning of the fourth century, the orator Lysias, showing no concern for historical accuracy, declared “our ancestors chose as nomothetae [that is, lawgivers] Solon, Themistocles and Pericles.”1 There was no mention of Cleisthenes or Ephialtes in this idealized evocation of the ancestral constitution, the patrios politeia. That omission was in no way surprising. “The fact is that, in Athenian minds, there had been no institutional innovations except in great periods that could be identified with a single man known and recognized by the whole community.”2 In accordance with a mechanism well charted in the Greek world, as elsewhere, important changes were always associated with one great man in particular. As recollection of events faded, the collective memory effected a simplification and stylization that tended to associate the introduction of a variety of measures with certain leading figures. The Spartans thus attributed a whole collection of economic, social, and institutional reforms to one single semimythical lawgiver, Lycurgus, despite the fact that the Spartan kosmos was set in place only gradually; and in just the same way, the Athenians associated the creation of their city as a political community—the famous synoecism—solely with the name Theseus—even though the process had clearly taken place only gradually in the course of a considerable period of time.

The ancient authors tended to attribute to certain men far more than they had, in truth, accomplished, thereby eclipsing other historical actors who were just as important. Cleisthenes the lawgiver remained in the shadow of Solon, who was considered to be more consensual, just as Ephialtes was reduced to a mere puppet manipulated by Pericles:3 that process of compression initiated in the fourth century found its fullest expression in Plutarch’s Life, which turned Pericles into the man of providence for the entire pentēkontaetia.

Does this mean that we should submit to a radical revision the image of an all-powerful Pericles, on the grounds that it resulted from a biased functioning of the collective memory that had been further amplified by the preconceptions of the ancient authors? To do so would, to say the least, be overhasty. In truth, that personal cult was not a purely a posteriori reconstruction, but instead was a theme that had already been elaborated in the fifth century, as several sources of evidence show. Even then, Thucydides was presenting the stratēgos as “the first of the Athenians” (1.139), who, unchallenged, dominated the city’s whole political life. According to this historian’s account, Pericles seems hardly even to belong to the civic community, so outrageously does he dominate it: he alone confronts the anger of all the Athenians, who form a homogeneous block facing him, before obliging the entire city (xumpasa tēn polin), purely by the force of his oratory, to recognize his superiority, his arkhē (2.65.1–2). According to Thucydides, the stratēgos even managed to subjugate the people with its own consent: “he restrained the multitude while respecting their liberties [kateikhe to plēthos eleutherōs], and led them rather than was led by them” (2.65.8).4

Nor was the historian Thucydides alone in expressing that opinion. In Pericles’ lifetime, already, the comic poets had delighted in setting the omnipotence of the stratēgos on stage, but in their case, did so in order to stigmatize it. They even went so far as to compare Pericles to the king of the gods, Zeus, although there was nothing complimentary about the assimilation, for, by calling him an Olympian, they were drawing attention to his hubris.5 Moreover, as well as describing him with that insolent label, the comic authors depicted him as a man who held quasi-absolute power. According to Telekleides, a contemporary of Pericles, the Athenians had handed over to him “with the cities’ assessments, the cities themselves, / to bind or release as he pleases, / their ramparts of stone to build up if he likes, and / then to pull down again straightway, / their treaties, their forces, their might, peace and / riches, and all the fair gifts of good fortune.”6 So it would seem that it was not just in foreign policies that Pericles did as he pleased, but also within the city; according to this poet, the citizens had abdicated their own sovereignty in his favor.

More alarming still, one deeply rooted tradition linked Pericles with the tyrants of Athens, the Pisistratids. This dark legend can already be detected, reading between the lines, in the ambiguous account of the birth of the stratēgos recorded by Herodotus. Just before giving birth to Pericles, his mother was said to have dreamed that she produced a lion.7 Although the analogy has certain heroic resonances,8 in a democratic context it is, to say the least, equivocal. For it links Pericles with Cypselus, the tyrant of Corinth, whose mother had a similar dream. Above all, however, it linked him with Hipparchus, the son of the tyrant Pisistratus who, also in a dream, had been compared to a lion and was destined to suffer a dire fate.9

As his opponents saw it, that was not the only link that bound Pericles to the tyrants of Athens. The very features of his face rendered him suspect. According to Plutarch, “it was thought that in feature he was like the tyrant Pisistratus; and when men well on in years remarked also that his voice was sweet and his tongue glib and speedy in discourse, they were struck with amazement at the resemblance” (Pericles, 7.1). Moreover, quite apart from his physical appearance, his network of friends evoked the memory of tyrants and those close to him were described as “the new Pisistratids” (Pericles, 16.1).

The stratēgos may well also have been compared to those controversial figures on account of the policies that he pursued. Some aspects of his actions as leader of the city were certainly reminiscent of certain initiatives of the Athenian tyrants. When he reorganized the Great Panathenaea so as to secure a greater place for musical competitions, Pericles was following in the footsteps of Pisistratus, who had, if not created, at least lent new luster to this great Athenian festival.10 Likewise, the construction policies of the stratēgos recalled Athens’s tyrannical past. The gigantism of the Parthenon must have been regarded as an echo of the immense temple of Zeus Olympius, the construction of which, to the south east of the Acropolis, had been launched around 515 B.C. by the Pisistratids who, however, did not have time to complete it.11 In suggesting that the embellishment of the city was, as Plutarch claimed, “manifestly subjecting it to tyranny” (Pericles, 12.2), Pericles’ opponents no doubt hoped to associate the stratēgos’s monumental policies with the detested memory of the Pisistratids.

The monumental program launched by Pericles on the Acropolis played a crucial role in the process that led to Pericles being depicted as an all-powerful monarch. To some extent, the ancient sources did represent the stratēgos’s power as a reflection of the Parthenon, majestic, intimidating, even overwhelming, thereby transforming the magistrate into an emperor so intent on his building projects that he eluded all popular control.

The Builder-Emperor

If Plutarch so greatly admired Pericles, despite all his “demagogic” policies, it was primarily on account of the “great works” with which the biographer associated him so closely. In his final comparison between Pericles and Fabius Maximus, Plutarch expresses his boundless admiration for those buildings that, in a way, increased the prestige of the whole of Greece in comparison with the triumphant Rome of the early centuries of its empire: “By the side of the great public works, the temples and the stately edifices with which Pericles adorned Athens, all Rome’s attempts at splendour down to the times of the Caesars, taken together, are not worthy to be considered.”12 In this way, Plutarch explicitly compares the action of the stratēgos to that of the Caesars. His monumental policies make him a prefiguration of the Roman emperors—in particular, Hadrian, who was a contemporary of the biographer and who, out of a sense of philhellenism, restored the edifices of Athens that were built under Pericles.13

Was this simply a later idea that emerged at the time when Plutarch was composing his Lives, as a result of a kind of contamination from the Roman imperial model? Not at all. In his own lifetime, the stratēgos was already associated with the monuments constructed at the peak of his career. The comic poets represented him as “carrying the Odeon on his head”;14 and one century later the orator Lycurgus of Athens, himself also a great builder who completed the construction of the theater of Dionysus, redesigned the Pnyx, and restored the temples of the Acropolis, wrote as follows: “Pericles, who had conquered Samos, Euboea, Aegina, and had constructed the Propylaea, the Odeon, the Parthenon, and had collected ten thousand talents for the Acropolis, was crowned with a simple crown of olive leaves.”15

However, even if this vision of an architect-Pericles frequently recurs in the ancient sources, for a number of reasons it calls for qualification. In the first place, we should distinguish between the edifices that are “Periclean” because Pericles himself proposed them and the monuments that are called “Periclean” only because they were constructed at the time when the stratēgos wielded influence in the city.16 If we credit the testimony of the orator Lycurgus, only the Odeon, the Parthenon, and the Propylaea—the last conceived by Mnesicles and all constructed in the five years between 437 and 433—should be attributed to the direct initiative of Pericles. To be sure, he also played a role in the construction of the Long Walls, which constituted a crucial element in his defense strategy. Nevertheless, he was not alone in taking part in their construction: Thucydides does not even mention his name in this connection,17 and Plato’s Socrates links him with only the construction of the inner wall that reinforced the northern wall that connected the city with Piraeus.18

Next, even Pericles’ supposed control of the work sites in which he was directly involved needs qualification. So it is, to put it mildly, mistaken to speak of “the labors of Pericles” as if they were comparable to the “labors of Heracles.” Pericles was no Hellenistic king, let alone a Roman emperor who, on his own, as an autocrat, decided upon the constructions to be undertaken. Every one of his projects was submitted to a vote of the Assembly that also decided how to finance it. Architects produced plans, models, and estimates, all of which were submitted for the approval of the Council. Magistrates then proceeded to adjudicate on the proposed works,19 which, once started, were subject to the intrusive control of a college of ten epistatai elected by the Assembly.

Given this context, when Plutarch, on the subject of the Odeon, declares that Pericles “supervised” (epistatountos) the construction (Pericles, 13.9), the biographer was clearly misrepresenting the reality. Only two possibilities are plausible: either he was referring to the official post of an epistatēs, the supervisor of a construction site, elected by the people, in which case he forgets that the stratēgos was obliged to agree with the other nine members of the commission;20 alternatively, he was assuming that someone held the power of general supervision over all such works, and that is something that is nowhere attested by the contemporary sources.

Plutarch’s testimony also needs to be considered cautiously where he writes of the building sites on the Acropolis where, if we are to believe him, “everything was under Phidias’s charge and all were under his superintendence, owing to his friendship with Pericles.” For in the first place, strictly speaking only the construction of the statue of Athena Parthenos can be attributed to the hand of Phidias; and second because, in the case of every one of his projects, Pericles had to persuade the Assembly to vote in favor of them and was obliged then to submit to controlling procedures that were beyond his own official powers. The ancient authors tend to ascribe to the stratēgos monuments that were in fact constructed both by the people and in the name of the people. This conflicting information is laid bare whenever it is possible to compare literary sources to the epigraphical documentation. Whereas Plutarch presents Pericles as the one who dedicated the monumental statue of Athena Hygieia, the foundation stone discovered on the Acropolis mentions only the Athenian people; the name of the stratēgos does not appear at all.21

One thorny question nevertheless remains. How should we treat the claims of Lycurgus who, one century later, insisted on personalizing the great works produced between 450 and 430? That biased presentation makes sense once it is set in context. Clearly playing on the idea of a mirror image, by recalling memories of Pericles, Lycurgus was aiming to enhance his own actions as the builder who restored the Acropolis monuments. By magnifying the stature of the stratēgos, he hoped to increase his own.

So should we deny Pericles any role in the great building projects that, from the mid-fifth century onward, multiplied in Athens, on the Acropolis, and on Cape Sunium? To do so would be to go too far, redressing the balance in an excessive manner. Certain documents allow us to glimpse how, within the framework of this concerted monumental policy, the collective will and individual initiative interacted. To come to a clearer understanding, we need to turn away from the domain of great stone monuments and consider the construction of more modest structures: fountains. A fragment of a decree dating from 440–430 B.C. mentions the provision of a fountain at Eleusis and explains how the project was financed: the Assembly decided to honor Pericles, Paralus, and Xanthippus, and his other sons, but to meet the costs by drawing on the money paid as tribute.22 Although fragmentary (the name of the stratēgos has been restored by epigraphists), this inscription does make it possible, with a certain degree of likelihood, to trace the process that led to the fountain’s construction. Initially, Pericles and his sons proposed to use their own resources to pay for either the whole or at least part of the monument. In doing so, they were acting as men keen to earn the favor of the people, for the provision of water was a matter of crucial importance in a Mediterranean land blasted by the sun and with insufficient supplies of water,23 not only for physical survival but also for performing numerous rituals both civic and private, such as lustrations and sacrifices, nuptial baths, and the washing of corpses. The people thanked them for this proposal but never theless declined the offer and eventually financed the project using funds received as tribute from the allies.24

This interaction between individual initiative and popular control echoes an episode recorded by Plutarch that likewise involves polemics sparked off by the financing of major architectural works:

Thucydides and his faction kept denouncing Pericles for playing fast and loose with the public moneys and annihilating the revenues. Pericles therefore asked the people in assembly whether they thought he had expended too much, and on their declaring that it was altogether too much, “Well then,” said he, “let it not have been spent on your account, but mine, and I will make the inscriptions of dedication in my own name [tōn anathēmatōn idian emautou poiēsomai tēn epigraphēn].” When Pericles had said this, whether it was that they admired his magnanimity or vied with his ambition to get the glory of his works, they cried out with a loud voice and bade him take freely from the public funds for his outlays and to spare naught whatsoever (Pericles, 14.1–2).

As in the case of the Eleusis fountain, the Athenian people were definitely keen to preserve their own major responsibility for great works; these had to redound to the glory of the whole community, not distinguish private individuals (idiōtai). All the same, Pericles’ influence was by no means minimal in the process of decision-taking, for he seems to have acted as the spur or even the initiator for the decisions taken by the community. The great works thus appear to have been the product of close negotiation between the people and the members of the Athenian elite.

However crucial Pericles’ influence on monumental policy may really have been, his name rapidly became associated with these grandiose constructions and this helped to confer upon him exceptional political stature in the eyes of the western world. And there was another element that supported this impression of Periclean domination: namely, the introduction, for the first time, of pay for civic services. In the ancient sources, the creation of the misthoi was certainly interpreted as a symbol of the patronage that Pericles exercised over the Athenian people, reducing it to a passive recipient of the great man’s benefactions.

The Beneficent Patron

In the second half of the fourth century, already, the author of the Constitution of the Athenians was defending such an analysis, and Plutarch later concurred with his account:

Pericles first made service in the jury-courts a paid office, as a popular measure against Cimon’s wealth. For as Cimon had an estate large enough for a tyrant, in the first place he discharged the general public services in a brilliant manner, and moreover he supplied maintenance to a number of members of his deme; for anyone of the Laciadae who liked could come to his house every day and have a moderate supply, and also all his farms were unfenced, to enable anyone who liked to avail himself of the harvest. So as Pericles’ means were insufficient for this lavishness, he took the advice of Damonides of Oea …, since he was getting the worst of it with his private resources, to give the multitude what was their own; and he instituted payment for the jury-courts; the result of which according to some critics was their deterioration, because ordinary persons always took more care than the respectable to cast lots for the duty.25

Within this framework of Aristotelian analysis, the misthos was represented as a means for Pericles to rival the wealth of Cimon and become the patron of the people, which this collective gift had the effect of infantilizing. However, that version of the situation needs to be considered with circumspection. By the late 450s, Cimon no longer held any real political power. He had been ostracized ten years earlier and, although he was recalled to Athens in 451, his influence must by then have been limited.26 It is above all the interpretation given by the Constitution of the Athenians that needs to be reexamined. Its author analyzes the pay given to jurors from a typically anti-democratic point of view (later emulated by Plutarch27), regarding it simply as a way of buying the people and, for Pericles, a means by which to turn himself into the patron of the poorest of the Athenians. According to that author, the introduction of the misthos was simply the fruit of a rivalry between aristocrats before which the people were mere spectators mechanically tending to support whichever side seemed the more generous.

As Pauline Schmitt Pantel has shown, that polemical interpretation deserves radical revision. With the creation of the misthos, Pericles was not establishing a new form of patronage—community patronage—to take over from private patronage, which Cimon embodied, as is clear for two reasons. In the first place, the misthos was not distributed by any identifiable individual, but by the community itself. So its assignation created no personal dependence between donor and recipient. Instead, it was the community that redistributed to a particular fraction of itself (the judges) wealth that it considered them to deserve. Second, its aim was radically different from that of private patronage: far from being a form of assistance, as was claimed by the detractors of radical democracy, this payment was awarded for active participation in the city institutions and so in no sense had an infantilizing effect.28

Instead of being a measure reminiscent of the Roman client-system, the introduction of the first misthoi diminished the influence that members of the Athenian elite could acquire through patronage. However, it never quite ousted the latter phenomenon, if only on account of the size of the sum of money paid, which was relatively small, certainly not enough to satisfy the needs of the poorest citizens.29 However that may be, the payments did not turn Pericles into the unchallenged patron of the Athenian community.

By now, at the end of our investigation, that supposed Periclean monarchy seems no more than a myth. The great construction works and the establishment of the misthos testify to the growing sovereignty of the dēmos just as much as to the domination of the stratēgos. Not only was Pericles obliged constantly to work with the other magistrates, but, both institutionally and socially, he was placed under the strict control of the Athenian people.

PERICLES UNDER CONTROL: THE POWER OF THE ENTIRE COMMUNITY!

One of Many Magistrates

Pericles never held military power on his own. The stratēgoi always acted in a collegial fashion, never individually:30 a single magistrate could never impose his will upon his colleagues, unless, that is, they wished him to do so. So his influence has probably been overestimated, partly as a result of the point of view adopted by the literary sources and the context in which they were produced. The comic writers based their craft on personal attacks and always set particular individuals on stage, often enough exaggerating their influence the better subsequently to demolish them. It was as if one were to pass judgment on the British political scene, gauging it solely in relation to the TV series Spitting Image, a satirical puppet show. As for Plutarch, his biographical viewpoint inevitably focused excessively on his particular hero, and it did so the more emphatically given that he was writing within a political framework—the Roman Empire—in which personal power had become the norm.31

An attentive rereading of the texts suggests that we should adopt a more circumspect attitude. Although Thucydides is always quick to ascribe unequaled domination to Pericles, he also mentions plenty of other important actors in the period between 450 and 440,32 at both the military and the diplomatic levels. First, at the military level it is the stratēgos Leocrates who is in command in the war against the people of Aegina in the early 450s (1.105.2); Myronides distinguished himself at Megara (1.105.3), as did the spirited Tolmides both at Chalcis and against the Sicyonians in 456/5 (1.108.5), before suffering a bitter defeat at Coronea in Boeotia in around 447 (1.113.2). In the years between 440 and 430, the stratēgos Hagnon seems to have held all the key roles. He was stratēgos alongside Pericles in the second year of the campaign against Samos (440–439),33 and was then, in 437/6,34 sent to found the colony of Amphipolis in Thrace, which was a great honor for him. In fact, Hagnon was judged by the Athenian people to be sufficiently powerful to deserve ostracism,35 although, in the event, not enough votes favored his banishment. Second, at the diplomatic level, Pericles clearly remained in the background—whether or not deliberately is not known—in the negotiations with the Spartans. The Thirty Years’ Peace was negotiated by Callias, Chares, and Andocides in 446, and Pericles was not even present at the negotiations.36 Similarly, at the time when the plague was ravaging the city and the Athenians sent ambassadors to parley with the Spartans (Thucydides, 2.59), this was clearly against the advice of the stratēgos.37

It is true that the posthumous aura of Pericles eclipsed many actors of the time, but they too shaped the destiny of the Athenian city in the course of those troubled decades. Throughout his career, the stratēgos inevitably had to share power, as was the custom in Athens, and above all had to submit to popular control. In the final analysis, it was the people who remained sovereign. However persuasive Pericles may have been, his influence was only temporary and could at any point be challenged by a change of heart on the part of the dēmos. As there were no political parties in Athens, nor any stable majority, every decision was the subject of negotiation between the orator and the people. The balance was precarious, and the situation of orators was often uncomfortable, for the popular assembly could change its mind and sometimes did so very rapidly, retracting its earlier commitments. Not long after Pericles’ death, Thucydides mentions two successive assemblies, the second of which reversed the decisions made a few days earlier on the fate of the Mytilenaeans who had revolted in 427 B.C. Even an orator with a huge majority of votes in favor of his advice on one day could find himself totally rejected on the next.38

In a wider sense too, the people exercised strict control over the orators and stratēgoi, maintaining them in a perpetual state of tension by resorting to more or less formalized supervision.

Multiform Institutional Supervision

In Athens, the stratēgoi and, more generally, all incumbents of magistracies were submitted to frequent and persnickety controls. These checks involved, in the first place, a rendering of accounts at the end of a magistrate’s mandate, necessitating a double examination. In the fourth century—and probably as early as the fifth—stratēgoi had to face a commission of controller-magistrates, the logistai, who verified all financial aspects of their management. In cases of proven irregularities the logistai, who were selected by lot from among all the citizens, could refer the affair to the courts. Furthermore, the stratēgoi could be prosecuted by any citizen before the members of yet another committee, an offshoot of the council. These were the euthunoi. If they judged the complaint to be well founded, they passed the case on to the competent magistrates (thesmothetai), who then organized a trial.39

Historians have for many years maintained that, in cases where a stratēgos was reelected, this procedure was omitted for practical reasons—for instance, the magistrates might be on a mission far from the city, rendering the examination impossible. In that case, Pericles would not have had to render any accounts during the fourteen years in which he had, without fail, been reelected; and this would have greatly diminished the control exercised over him. But in reality this hypothesis has to be abandoned. In the first place, expeditions of long duration were rare in the fifth century; Pericles was never away from Athens for more than a year, except at the time of the war against Samos, which lasted from 441 to 439. Second, Pericles did render his accounts after the Euboean revolt, in 447/6, despite the fact that he was reelected as stratēgos for the following year. “When Pericles, in rendering his accounts for this campaign, recorded an expenditure of ten talents as ‘for sundry needs,’ the people approved it without officious meddling and without even investigating the mystery” (Plutarch, Pericles, 23.1). So it is clear that stratēgoi did render their accounts even when they were reappointed to their posts.40

One anecdote recounted by Plutarch conveys just how stressful the procedure was for Athenian magistrates, even the most influential of them: “[Alcibiades] once wished to see Pericles and went to his house. But he was told that Pericles could not see him; he was studying how to render his accounts to the Athenians. “Were it not better for him,” said Alcibiades, as he went away, “to study how not to render his accounts to the Athenians?” (Alcibiades, 7.2). Alcibiades was Pericles’ evil genius, but this remarkable role-reversal turns the undisciplined youth’s tutor, Pericles, now no longer Alcibiades’ teacher, into his pupil in the school of crime!

Over and above that exercise of control, at the end of a magistrate’s duties, the Athenians had the power to depose the city’s principal magistrates even while they were still carrying out their official mandate: each month the Athenians voted, with a show of hands, on whether or not they confirmed their magistrates in their positions, epikheirotonia tōn arkhōn.41 In the event of a negative vote (apokheirotonia), the magistrate was forthwith deposed. This was probably the procedure of which Pericles was a victim in 430/429, when he was dismissed from his duties as a stratēgos.42 Following that first sanction, the stratēgoi could be arraigned for high treason (eisangelia). Treason was a fairly vague notion to the Athenians; losing a battle or being suspected of corruption was sometimes enough to set the procedure in motion. Pericles himself probably suffered this bitter experience in 430/429, when, after being deposed, he was judged and sentenced to pay a very large fine.43 According to Ephorus, the source for Diodorus Siculus,44 his accusers blamed him for being corrupt, and this probably explains why Thucydides, in contrast, goes to such pains to emphasize the incorruptibility of Pericles in his final panegyric for the stratēgos (2.65.8).

Last, the Athenians also had at their disposal a more general mode of control over members of the city’s elite: the procedure of ostracism. This was instituted following Cleisthenes’ reforms; it consisted of exiling for a period of time any figure considered to wield too much influence. This limited the risks of a return to tyranny. The decision did not need to be justified—a fact that many ancient authors considered to be scandalous. It was applied for the first time in 488/7 B.C. against a certain Hipparchus, son of Charmus, who was probably related to the family of the former tyrants of Athens. In 485 B.C., Pericles’ father was a victim of the procedure of ostracism, but he was recalled at the time of the Persian Wars. According to Plutarch, it was because Pericles feared that he, in his turn, might be ostracized that he sided with the dēmos. Ostracism thus constituted a permanent threat that hung over the heads of the most influential Athenians and encouraged them to conform to popular expectations.

Ostracism, which was voted upon every year, took place in two stages. In the sixth month of the year, a preliminary vote that took the form of a show of hands decided whether or not to initiate the procedure. If this was in principle accepted, a second (secret) vote took place to decide who was to be condemned. This vote was conducted using potsherds (ostraka) upon which the citizens wrote the name of the man they wished to ostracize—a process that provides a good indication of the relative literacy of Athenian society. The individual with the most votes was then exiled, provided that a quorum of at least 6,000 voters had taken part. Those graffiti did not always stop at naming a victim but in some cases also mentioned the reasons that motivated the vote. It sometimes happened that the sexual reputation or even sexual behavior of men involved in politics was invoked to justify their exile. While some were blamed for their excessive wealth—such as one “horse breeder”—others were accused of adultery (moikhos). As for Cimon, Pericles’ first opponent, on one of the ostracism shards bearing his name (figure 9), he was even accused of maintaining an incestuous relationship with his sister, Elpinike: “Cimon [son of] Miltiades, get out of here and take Elpinike with you!”45 Because a vote of ostracism did not need to be justified by any particular offence that was penally reprehensible, it rested partly on the accusations laid against politicians for their personal behavior.46

FIGURE 9. Ostraka of Cimon (ca. 462 B.C.). From S. Brenne, 1994, “Ostraka and the Process of Ostrakophoria,” in W.D.E. Coulson et al., eds., The Archaeology of Athens and Attica under Democracy. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books, 13–24, here fig. 3-4, p. 14.

The fact was that the Athenians not only set controls upon the Athenian elite by imposing numerous laws that affected them. They also did so by circulating rumors about their behavior that were first given expression in the theater and from there spread throughout the city. In this way, they exerted strong moral and ideological pressure upon those responsible for important duties.

Omnipresent Social Controls

The Invectives of the Comic Poets: Pericles on Stage

Comic poetry, which was full of allusions to contemporary political life, fulfilled a function of social control over the members of the Athenian elite. In the orchestra of the theater of Dionysus, at the time of the Great Dionysia or the Lenaea, the poets often directed personal attacks—onomasti kōmōidein—against the individuals most deeply involved in civic life. Politicians were directly named by the actors performing before the entire assembled people. Gibed at or even ridiculed, they were attacked as much for their public actions as for their lifestyles and their behavior in private.

Pericles was a particular target of such personal attacks. His relationship with Aspasia and his supposed sympathies for tyranny were frequently mocked on stage.47 Such accusations peaked at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War. Plutarch certainly testifies to the growing hostility then surrounding the stratēgos: “Many of his enemies [beset him] with threats and denunciations and choruses sang songs of scurrilous mockery, designed to humiliate [ephubrizontes] him, railing at his generalship for its cowardice and its abandonment of everything to the enemy” (Pericles, 33.6). In view of all this, it might seem but a small step to assuming that comedy—and, more generally, simply rumors—played a part in the stratēgos’s removal from power in 430/429. But that is a step that should not be taken.

In the first place, there were limits imposed upon the freedom of speech (parrhēsia) of the comic poets. The ancient sources even record certain episodes of censure in which Aristophanes and other comic writers were targeted, at particularly delicate moments in the history of Athens.48 Although the cases brought against comic poets are by no means all confirmed,49 a decree aiming to ban personal attacks in the theater does appear to have been passed in 440/439 at the instigation of Pericles; no doubt, the stratēgos hoped in this way to put a stop to the most virulent attacks launched against him while the city was engaged in the lengthy siege of Samos. However, this measure that had been approved within the context of a crisis was waived less than three years later;50 in the fifth century, no law restrained the freedom of speech of the comic poets for very long.51

Second, those gibes did not necessarily directly influence the Athenians’ voting in the Assembly. Even as he was being subjected to constant fire from his critics, Pericles was reelected without interruption from 443 to 429, and, similarly, Cleon retained the people’s confidence despite the success, in 424 B.C., of Aristophanes’ Knights, in which the demagogue was dragged through the mud in the person of an uncouth Paphlagonian.52 So such invectives seem not to have had much direct effect politically. There was a strong ritual dimension to those insults and outrageous claims, and their function was mainly cathartic. The violence of comic language stemmed more from a ritualized process of verbal abuse than from any clearly articulated political program.53

All the same, that is not to say that such attacks had no impact at all. They affected Pericles significantly, leading him to modify his behavior. The reason he decided, upon entering political life, to adopt a totally transparent way of life was precisely so as to try to avoid such verbal attacks.54 In order to avoid being attacked on the comic stage, politicians thus had good reason to keep a check on their own behavior and to adjust it to satisfy popular expectations. Comedy certainly did affect Athenian political life, not directly—by influencing the citizens’ votes—but rather indirectly, by reflecting in a magnifying mirror the “ethico-political” norms with which members of the elite were invited to conform.

The Strength of Rumors: The Goddess with a Thousand Mouths

The criticisms that were amplified in the theater, which acted as a sounding-board, started off in the Agora, where they circulated in a diffuse manner. As they passed from mouth to mouth and from ear to ear, rumors swiftly grew into an anomalous and sometimes disquieting collective phenomenon.55 Pericles was himself a victim of this gossip and these whispers that grew mysteriously without being associated with anyone in particular. Legetai or legousin, as the Greek texts put it: “it is said” or “they say.” This is the formula to which Plutarch resorts in order to convey the rumors surrounding the stratēgos, who was said to be transfixed with love for Aspasia, corrupting the wives of other citizens, and mixing with enemies of the city.56

Through what channels were these rumors spread? The poets would sometimes lend them their voices, but initially the rumors circulated in informal spaces, as murmurings in the shops or even in the meetings of phratries and other associations.57 The workplaces of certain craftsmen—barbers, cobblers, and fullers—constituted important meeting places,58 where information would gather to the point where it would even turn into veritable waves of opinion.59 Even before rumors became rife in public places, they would sometimes emerge in private ones. According to Plutarch, Pericles was the target of slander started by members of his own family, who were indignant at his intransigent attitude where financial matters were concerned: “Xanthippus, incensed at this, fell to abusing his father and, to make men laugh, publishing abroad his conduct of affairs at home, and the discourses that he held with the sophists” (Pericles, 36.2). It seems that, later, Pericles’ elder son even increased his attacks to the point of starting a rumor that his father was sleeping with his own (Xanthippus’s) wife (Pericles, 36.3)!

Even if these rumors were groundless, they were certainly not harmless. They forged collective beliefs that could not simply be swept aside by their victims. The fourth-century orators were even ready to recognize a degree of truth in them. According to Aeschines, “In the case of the life and conduct of men, a common rumor which is unerring does of itself spread abroad throughout the city,”60 which was why, probably at the time of Cimon and Pericles, the Athenians had devoted a cult to it, “as the most powerful of goddesses” (hōs theou megistēs).61 The philosopher Plato was likewise astonished at the amazing power of rumor62 that, praising some and denigrating others, defined norms of behavior that were all the more influential because they were not formalized. Phēmē thus acted upon the very heart of reality, as “a great subterranean power, an essential part of what is held to be true.”63 It oriented the actions of the Athenian leaders, who were often enough obliged to dance to the tune of slander, in order to save their very lives: rumor, “the eternal accuser” (katēgoron athanaton),64 dogged the steps of the politicians who, as a result, were forced to adjust their behavior.65

Chatter and malicious gossip formalized the fears and expectations of the dēmos, structured public opinion, and surreptitiously defined the behavior that the people expected from the Athenian elite. Rumors, although informal, undeniably affected the behavior of the political actors just as much as or even more than legal procedures did. We should not regard social pressure and institutional controls as radically opposite. The fact was that the people exercised a kind of informal control at the very heart of the city institutions: speaking in the Assembly, orators had to cope with reactions from the dēmos that were sometimes brutal and unpredictable, as Pericles well knew, often in glorious circumstances, but sometimes in bitter ones.

Heckling in the Assembly: Orators under Pressure

Even in the Ekklēsia, which is where the ancient authors ascribe the most influence to him, Pericles’ speeches were always controlled by the crowd. The people did not hesitate to express their disapproval noisily or even to heckle the orators despite—or because of—all their rhetorical skills.66 Even though most citizens did not, themselves, dare to speak, that does not mean that they remained passive, silently gaping as they listened to the speeches delivered from the tribune. Time and again, the orators had to contend with great bursts of noisy applause, protests, whistles. and laughter and were even faced with heckling (thorubos), as many speeches of the Attic orators testify.67 “Vocal interruptions and heckling in court and Assembly undermined the speaker’s structural advantage as the focus of the group’s attention and reminded him that his right to speak depended on the audience’s power and patience.”68 The heckling stemmed from the normal Athenian exercise of freedom of speech, and its effect was to regulate the functioning of collective institutions while, in contrast, religious silence on the part of the masses was characteristic of peoples that were subjected to authoritarian regimes.69

Pericles was on several occasions forced to confront a restless, even hostile, crowd that was perfectly prepared to interrupt him in the Assembly. According to Plutarch, the stratēgos was initially the target of violent criticism at the time when his ambitious building projects were discussed. Led by his political opponent Thucydides and his followers, the revolt broke out right in the middle of the discussions held on the Pnyx: “They slandered him [dieballon] in the assemblies, ‘The people has lost its fair fame and is in ill repute because it has removed the public moneys of the Hellenes from Delos into its own keeping.’” (Pericles, 12.1). Nor did the hostility aroused by the great construction works abate. In the course of another Ekklēsia meeting, Pericles had to render an account of the money provided for this vast building program. Faced with the people’s violent recriminations, right there in the Assembly, the stratēgos offered to complete the constructions using his own funds, on condition that all the merit would then go solely to him. But the Athenians rejected that solution and even “cried out with a loud voice [anekragon] and bade him take freely from the public funds for his outlays and to spare naught whatsoever.”70 While this episode certainly draws attention to Pericles’ persuasive powers, it also indicates the limits of his influence. Placed in danger on the tribune, the stratēgos could defuse the hostility of the people only by persuading it of how useful his project would be for the whole community; it was because these constructions increased the prestige of their city that the Athenians now noisily approved of the stratēgos and his building policy.

When the conflict against the Peloponnesians began, that public pressure became more alarming. In 430, the stratēgos needed all his skills to calm down the anger of the people that now found itself enclosed within the city walls and infected by the plague: “After the second invasion of the Peloponnesians the Athenians underwent a change of feeling, now that their land had been ravaged a second time while the plague and the war combined lay heavily upon them. They blamed Pericles for having persuaded them to go to war and held him responsible for the misfortunes which had befallen them, and were eager to come to an agreement with the Lacedaemonians. They even sent envoys to them, but accomplished nothing. And now, being altogether at their wits’ end, they assailed Pericles” (Thucydides, 2.59.1–2). It was, according to Thucydides, only with great difficulty that he eventually managed to swing his audience round in his favor.71 As Arnold Gomme remarks: “Perhaps nothing makes more clear the reality of democracy in Athens, of the control of policy by the ekklesia, than this incident: the ekklesia rejects the advice of its most powerful statesman and most persuasive orator, but the latter remains in office, subordinate to the people’s will, till the people choose to get rid of him.”72

A few months later, even the magic of his oratory was no longer enough. Thucydides does not dwell on this episode, which does not reflect well on his hero, but he does record that Pericles was relieved of his responsibilities as stratēgos at an Assembly session, probably following an epikheirotonia tōn arkhōn procedure. “They did not give over their resentment against him until they had imposed a fine upon him” (Thucydides, 2.65.3). Dismissed from the tribune and brutally stripped of his magistracy, Pericles retired to his oikos until a little later, when the remorseful Athenians summoned him back.

Without doubt, heckling from the people had the power to counterbalance the rhetoric of even the most distinguished orators: these inarticulate murmurs could neutralize any logos, however persuasive it might be. It was in this way that the people tamed its elite leaders: far from dominating their audience, the Athenian leaders found themselves controlled by the dēmos, at the mercy of its more or less spontaneous reactions. Faced with ever possible dissent, it was very difficult for the orators to propose points of view that were too much at odds with popular expectations.

Persnickety institutional procedures, tumultuous popular interventions in the Assembly, outrageous comic insults, and obsessive rumors: in the course of the fifth century, all these progressively combined to promote the political and ideological dominance of the Athenian dēmos. Plato, in the next century, was the writer who best described the powers by which the elite groups were tamed by the people—a process that the philosopher considered to be seriously pathological.73 Democracy was, in other words, for him a leveling downward. Plato developed an eminently polemical point of view toward the Athenian city, but he was fundamentally right, for in the fourth century, orators could no longer openly distinguish themselves from the common crowd on the basis of their supposed superiority.

Yet this evolution was by no means always interpreted as a crippling defect in Athenian democracy. All that Plato denounced was, on the contrary, celebrated by Demosthenes in his speech On the Crown (§ 280): “But it is not the diction of an orator, Aeschines, or the vigour of his voice that has any value: it is supporting the policy of the people [hoi polloi] and having the same friends and the same enemies as your country.” Demosthenes recognized the imperious need for the rhētores to fall into line with popular norms, which in effect, in the fourth century, meant with the demagogues (in the neutral sense of that term) and to strive constantly to diminish the social distance that separated them from the ordinary citizens.74

Was this conclusion reached by the fourth-century orators and philosophers something that was already sensed by Pericles and the age in which he lived? Not entirely. The life of the stratēgos testifies to the fragile balance maintained between, on the one hand, the persistent prestige of members of the Athenian elite and, on the other, the growing power of the people. But even if Pericles still stood out from the majority of the Athenians by virtue of both his wealth and his charisma as an orator, his behavior also reflected a desire to conform with the aspirations of the people. It was a provisional compromise that continued to evolve in the decades that followed. In this respect, Pericles’ career symbolizes a point of equilibrium just as much as a moment of rupture: to the Athenians, his death seemed to mark the end of an era. To be sure, it was far from being a total reversal, for the demagogues who succeeded him were by no means newcomers who had emerged from the gutter and now proceeded to turn the city upside down!75 Nevertheless, they were the first leaders who explicitly paraded their close social and cultural ties with the people, thereby incurring the wrath of members of the traditional elite, who still clung on to their own distinction. Indeed, the death of the stratēgos brought about not so much a revolution, but rather a revelation. Once Pericles had gone, it was no longer possible to deny the plain fact: pace Thucydides, Athens certainly was now, in fact as well as in name, a democracy.

So, in order to speak dispassionately of Pericles, should we put aside Thucydides and his biased judgements? It would be impossible to do so, if only for historiographical reasons. However much of a caricature it may have been, the historian’s view has, ever since Antiquity and right down to the present day, lastingly influenced the way that the Periclean moment is interpreted. The fact is that, transmitted as it was by Plutarch, that view soon became a commonplace that was for the most part accepted totally uncritically by the Moderns. However, Pericles did need to recover his status as a “great man,” and this proved no easy matter. For a long time, the stratēgos occupied no more than a marginal place in references to Greek and Roman Antiquity: the “Age of Pericles” was a very long time coming.