2 The Life Hackers

I never expected to see anything about life hacking at the grocery store. But there, among the tabloids in the checkout line, was “the most useful magazine you will buy this year”: The Practical Guide to Life Hacks. This fifteen-dollar glossy had articles on how to love your job, twenty-six household tips to save money, a sixty-second fitness regime, and the secrets of happy families. The content of the magazine was not that different from that of Martha Stewart Living, sitting next to it. Self-help has long been a staple of the checkout line. But “life hacks” next to candy bars? How had this happened?

In the 1958 horror movie The Blob, a gelatinous space-born terror grows in size and danger with each person consumed. Just as some critics liken self-improvers to members of a cult, others liken the genre itself to a creeping horror—a characterization I also disagree with. In an article about how “self-help publishing ate America,” one critic writes that this “plague of usefulness” has “infiltrated and commandeered other fields in its drive to reproduce.”1 In his critical history of life hacking, Matt Thomas calls it a “technologized” and “colonizing” type of self-help, with a “rapacious” need to “apply the logic of the computer to all human activity”: “once it has colonized one domain, it looks for another to take over.”2 Even the grocery store is not safe.

It is easy to imagine life hacking as a fast-growing tumor on the omnipresent blob of self-help. Even so, this image fails us when it comes to understanding the character of life hacking, which is not a colonizing plague. Life hacking is, instead, the collective manifestation of a particular human sensibility, of a hacker ethos.

In the hacker’s sight, most everything is conceived as a system: it is modular, composed of parts, which can be decomposed and recomposed; it is governed by algorithmic rules, which can be understood, optimized, and subverted. There are boring systems, which hackers seek to automate and outsource, and interesting systems, which are novel and require creativity. Hackers like their gadgets, so setting up a new Wi-Fi kettle, even if it takes hours, can be more interesting than putting the kettle on every day. Similarly, experimenting with meal-replacing nutrition shakes can be more interesting than making lunch. Because life hackers are fond of systems, and everything can be seen as a system, they bring a surprising amount of enthusiasm and optimism to bear on many facets of life.

Life hacking did not spread because people were ingested or colonized. Rather, those who hack came to the fore, and they now have more opportunities to design their lives and our world according to their shared ethos—for better and worse. This ethos is individualistic, rational, experimental, and systematizing. As such, it’s well suited to this moment of far-flung digital systems. The Practical Guide to Life Hacks is evidence of life hacking’s relevance—even if the term itself is faddish. To get a better sense of the hacker ethos, let’s consider those most responsible for the emergence of life hacking: those who coined the term, popularized the practice, took it mainstream, and exemplify the lifestyle.

Alpha Geeks and Authorpreneurs

In February 2004, Danny O’Brien, a writer and digital activist, was one of the many tech enthusiasts converging on San Diego for the O’Reilly Emerging Technology Conference. However, O’Brien was not as interested in technology as he was in technologists’ habits. In the description for his life hacking session, he wrote that “alpha geeks” are extraordinarily productive, and he wanted to understand their secrets. He asked participants to share “the little scripts they run, the habits they’ve adopted, the hacks they perform to get them through their day.” Given how they benefit from these hacks, he wondered, “Can we help others do so, too?”3

O’Brien defines a hack as “a way of cutting through an apparently complex system with a really simple, nonobvious fix.”4 This is in keeping with the term’s origins, which originated from MIT’s Tech Model Railroad Club in the 1950s, specifically within the Signals and Power (S&P) subcommittee responsible for the electronics underneath the train platform. As Steven Levy writes in his history of computer hackers, the “S&P people were obsessed with the way The System worked, its increasing complexities, how any change you made would affect other parts, and how you could put those relationships between the parts to optimal use.”5 By 1959, the club had developed enough jargon that it issued a dictionary, which defined a hacker as someone who “avoids the standard solution.”6 This affinity for understanding and tinkering with systems, often by way of unconventional approaches, continues today. Often, hacking entails the bending, or breaking, of implicit rules and expectations.

Life hacking was born amid the crosscurrents of software developers and writers, a segment of the creative class. These are both professions in which practitioners are sometimes evaluated by the number of lines or words written. Such jobs also require a fair amount of self-discipline. It is difficult to focus on writing code or prose when so many digital distractions are at hand. And in 2004, with the resurgence of the online economy and faltering of print journalism, developers and writers were increasingly working independent of large corporations and mastheads. Nearly every developer of an app must play the part of an entrepreneur. Similarly, authors must increasingly play the role of what The Economist calls the “authorpreneur”: they must be their own publicists, game the best-seller lists, and do speaking tours.7 Today, they must also blog and podcast.

Cory Doctorow, one of the attendees of O’Brien’s session, fits the authorpreneur mold. Doctorow, like O’Brien, has worked for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit civil liberties group based in San Francisco. He is also a longtime contributor to the popular blog Boing Boing. And he is a successful science fiction author who often releases his works under a Creative Commons license; this permits readers to freely read and make copies of his books. Borrowing an aphorism from tech publisher and conference convener Tim O’Reilly, Doctorow has made books freely available “because my problem isn’t piracy, it’s obscurity. … Because free ebooks sell print books.” Doctorow even made this logic the premise of his first novel in 2003: Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom.8 The book’s protagonist lives in a world in which necessities are freely available. The distinguishing feature of life is “whuffie,” a real-time measure of social reputation, which is tracked and accessed via a brain implant. In such a world, whuffie determines relative rank, such as who gets a table in a crowded restaurant, and it’s instantly visible to everyone.

Doctorow exemplifies the authorpreneur, developing a significant following through his blogging at Boing Boing, fiction writing, activism, and San Francisco Bay Area connections—even if he was born in Canada and eventually left San Francisco for London and then Los Angeles. He was also an early promoter of life hacking. Doctorow was on the conference committee of the 2004 Emerging Technology Conference and posted his notes from the life hacking session. A few months later, in June, when O’Brien and Doctorow were in London for another conference, Doctorow again took notes at the life hacking discussion and posted them to Boing Boing. Doctorow had introduced Boing Boing readers—myself included—to life hacking, and he would also lend his “whuffie” to one of the first blogs dedicated to the topic.

43 Folders and Getting Things Done

In September 2004, Merlin Mann, an “independent writer, speaker, and broadcaster,” launched the blog 43 Folders. Before this, Mann had been a web developer, project manager, waiter, courtroom exhibit designer, and “enthusiastic but unprofitable indie rock musician”—among other things. And for the past decade, Mann has done most of what he does “in front of a MacBook in the western third of San Francisco.”9 Mann’s eclecticism, his fondness for Apple products, and his affinity with the Bay Area are common among early life hackers.

Mann named 43 Folders after a paper-based way of “tickling” one’s memory to complete tasks, using twelve monthly and thirty-one daily folders. (Twelve plus thirty-one equals forty-three.) This old-school, nondigital way of organizing tasks is described in David Allen’s 2001 book Getting Things Done (GTD), a source of inspiration to many life hackers. In his brief minutes of the first life hacking discussion in San Diego, Doctorow listed Getting Things Done as the top recommended reading for nascent life hackers. As soon as Mann saw Doctorow’s notes, “I knew I was with my people. I had been using GTD enthusiastically for a couple months at that point and immediately saw a bunch of common ground.”10

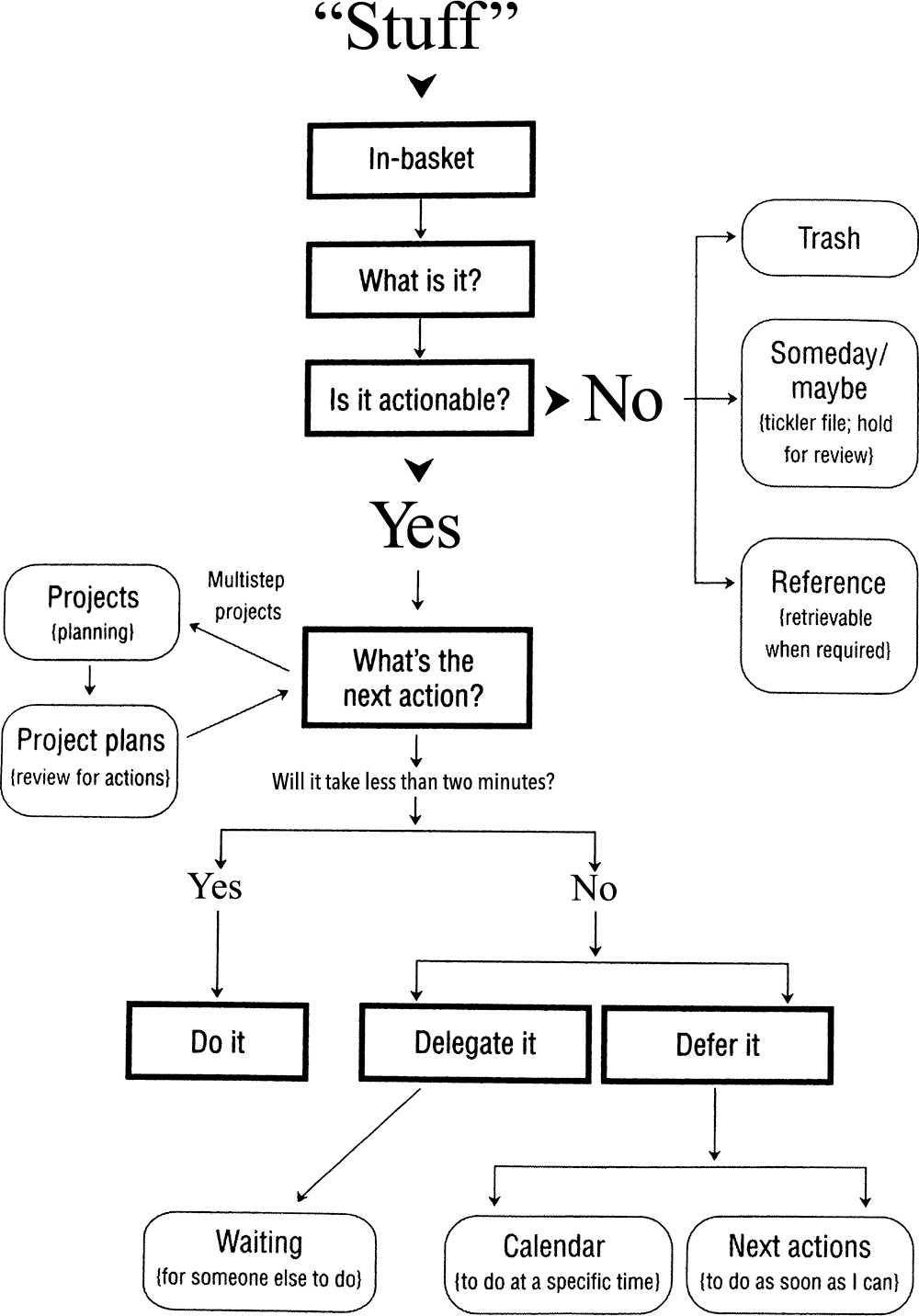

Allen’s Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity proposes a system wherein the incomplete tasks occupying your mind are captured and processed: they are prioritized, quickly dispatched (completed or trashed), or planned and substantively engaged. Stress is mitigated by way of an algorithm.

If the life hacking wave crested in 2004 with O’Brien’s neologism, Allen’s 2001 book served as its motivating current. The book was discussed and recommended at O’Brien’s first life hacking session and inspired the name and much of the content of Mann’s 43 Folders. And although Allen never mentioned hacks, he did speak of tricks: “the highest-performing people I know are those who have installed the best tricks in their lives.” Like a computer, people have inputs and install tricks. GTD, then, is a system for processing “all of the me ‘inputs’ you let into your life” so that your brain is released from the obligation to worry about them. Allen would later comment that geeks were early adopters of his system because they “love coherent, closed systems, which GTD represents.”11 Mann agreed and considered GTD “geek-friendly” for eight reasons, one of which is that “geeks love assessing, classifying, and defining the objects in their world”; life hacking was really just “a superset of GTD.”12

Figure 2.1

Processing workflow diagram from David Allen, Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity (New York: Penguin, 2001), 32.

At 43 Folders, some of Mann’s most popular early posts included “Getting Started with ‘Getting Things Done,’” “Introducing the Hipster PDA” (using index cards and a binder clip), and “Hack Your Way out of Writer’s Block.” In 2008, Mann wrote that “in no small measure, it was Cory Doctorow’s surpassingly generous linking and encouragement that shot my crummy little site to its cruising altitude. … Cory will have my deepest gratitude for using his considerable whuffie to almost singlehandedly put 43 Folders on the map.”13

In the following year, Mann joined with O’Brien to pursue the emerging life hacking phenomenon, but their efforts were short-lived. They cohosted a life hacking session at the 2005 Emerging Technology Conference and collaborated on a life hacking column for the new O’Reilly magazine Make. They also planned to write a book on the topic for O’Reilly’s “Hacks” series. (Tim O’Reilly’s publications and conferences were important venues for early computer hackers, and he was equally encouraging to the young maker and life hacking communities.)

Ironically, O’Brien and Mann never completed any books about life hacking.

O’Brien turned his attention toward digital activism and looks upon his early life hacking efforts with good-natured chagrin. In a 2010 interview, he conceded that he could be considered the “absent father of life hacking” because “I am such an alcoholic of systems. … I have tried them all and nothing works.” And he appreciates the irony of failing to write the book: his Electronic Frontier Foundation biography reads “it has been nearly a decade since he was first commissioned to write a book on combating procrastination.”14

Four years after the launch of 43 Folders, Mann expressed dissatisfaction with the superficiality of life hacking blogs and “‘productivity’ as a personal fetish or hobby.”15 In the following year, he announced he had a contract to write a book about “inbox zero,” his notion of ruthlessly keeping one’s inbox empty. Yet his posting at 43 Folders was flagging, and this book, too, was never published. In a rambling essay in April 2011, he confessed that “my book agent says my editor (who is awesome) will probably cancel My Book Contract if I don’t send her something that pleases her … today. Now. By tonight. Theoretically, I guess … uh … this.” Apparently, “this” did not please her, and his last post to 43 Folders was in October 2011. Like O’Brien, Mann describes his relationship with life hacking as troubled: “I’m not doing this because I’m great; I’m doing this because I’m terrible. I sometimes describe myself as feeling like a drunk in the pulpit, where if I don’t get there and talk and try to share what’s working for me, I could end up back on the bottle.”16 Today, Mann continues to be a jack of many creative trades. He still writes, even if he no longer updates 43 Folders, and offers his services as a productivity consultant. Otherwise, he spends much of his time as a contributor to geeky podcasts.

The life hacking mantle would have to be picked up by someone else.

Lifehacker and the Rational Style

Writing the first book of life hacks would fall to Gina Trapani, who also lived in California, though she now resides in Brooklyn. She describes herself as a “[software] developer, founder, and writer”—in keeping with the authorpreneur mold—and she launched Lifehacker in January 2005.

Trapani recalls that the idea for the website was “hatched back in late 2004” following what “Danny O’Brien cooked up earlier that year.” She saw Doctorow’s notes on Boing Boing, so “without Danny and Merlin, Lifehacker would have never happened. I owe both of these guys a huge debt of gratitude for their articulation of a concept that I literally launched a writing career upon.”17 In short order, Lifehacker became the most popular and successful purveyor of life hacking tips. Its early posts were a little more diverse than those of 43 Folders and included “Dishwasher tips,” “Soporific songs,” and “Windows keyboard shortcuts”—not something the Mac-centric Mann would touch. Three books based on material from the blog followed in 2006, 2008, and 2011.

Just as it was on 43 Folders, GTD was an early topic at Lifehacker, and Trapani was fond of Allen’s notion of “tricks.” Her first book was entitled Lifehacker: 88 Tech Tricks to Turbocharge Your Day, and her last book began with the quote from Allen about his respect for “those who have installed the best tricks in their lives.”18 In 2009, she handed editorship of the website over to a collaborator and returned to start-up life and writing code rather than prose.

Life hacking appeals to Trapani because she has “a very systematic way of looking at life.” Computer programs automate things, and in life hacking, she observes, “you kind of reprogram the way that you perform tasks, to make them a little faster and a little more efficient.” And once you have found an optimized routine, it only makes sense to share so others can “benefit from this and experience a system that another person has already tried.” This systems-oriented thinking is core to the life hacker ethos, as Trapani explains: “technically minded people have this very strong focus on making sense of the world and making things systematic and methodical.”19 There is some empirical evidence for this claim.

Psychologists speak of a cognitive style as a way of taking in and processing data; it’s a persistent personal attribute that is seen in patterns of thinking and behavior. Two different cognitive styles are often discussed: systematic (rational/analytic) and intuitive (associative/experiential).20 Intuitive thinking tends toward a larger, holistic view and relies upon the integration of intuition, feelings, and context. Systematic thinking seeks patterns and makes use of rules.

For those who enjoy Sudoku, part of the pleasure is discerning a puzzle’s internal logic and patterns. Among Sudoku fans, some of these patterns have evocative names, like the “X-Wing,” “remote pairs,” and “avoidable rectangles.” But for newcomers, these patterns are unnamed: they are subtle brain tingles trying to emerge into consciousness. Not surprisingly, a study has found that among new players, those with the systematic cognitive style improved with experience, unlike their intuitive peers. Two other studies have found an association between the systematic/rational style and computer students and hackers.21

Among life hackers, this mind-set has even become a matter of advocacy. When I was learning about productivity and nutrition hacking, I followed discussions at LessWrong, an online community dedicated to “refining the art of human rationality.” There I also learned about the Center for Applied Rationality, a small Bay Area nonprofit that offers workshops on cognitive biases so that we can begin “patching the problems” of human thinking. (“Patching” is a term for fixing buggy software.) There’s even a book, Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions, that advocates approaching personal and social concerns the same way computer scientists think about and solve their challenges.22

It’s not unreasonable to ask if this systematic style is associated with gender or autism. In a 1993 Wired article, Steve Silberman characterized autism as the “geek syndrome.” Given that autism is partially hereditary, Silberman asked if the concentrations of geeky folk in places like Silicon Valley meant that the genetics that contributed to their brilliance could, in subsequent generations, become debilitating. Subsequently, a controversial researcher has concluded that autism is the manifestation of a masculine hypersystemizing brain.23

The geek syndrome hypothesis is a contentious one, among both researchers and the public. It intersects with debates about gender difference and essentialism, cognitive difference and disability, and questions of identity and culture. In 2016, Silberman returned to the topic in NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity.24 Silberman describes the history of autism diagnosis and treatment, its association with early geek culture, its emergence in popular awareness, and the rise of parent and autist advocacy. In the intervening twenty-three years between his Wired article and NeuroTribes, Silberman realized that the geek syndrome is more complicated than he originally conceived.

I will return to how self-help culture is often gendered, but for the present, it is clear that the systematic style of thinking is central to life hacking, especially to the woman who succeeded in popularizing it. For Trapani, a life hack is a “systematic way to get something done in your life, whether that’s on your computer … or folding your socks.”25

The 4-Hour Workweek and Lifestyle Design

Although Lifehacker remains paramount, with more than a million monthly readers, dozens of life hacking sites exist. The content aggregator AllTop lists recent articles from about eighty life hacking sites including the blogs Zen Habits, Life Optimizer, and Unclutterer. Most of these sites are small, personal undertakings and not the sole occupations of their creators. Ironically, the person who made a career out of life hacking and took it mainstream does not often use the term.

Tim Ferriss is the author of a handful of New York Times best sellers, an investor (in the likes of Uber, Facebook, and Twitter), the creator of a top blog and podcast, and someone often included in annual lists of the innovative and powerful. Rather than describe himself as a combination of an author and entrepreneur, he prefers to list how others have described him. For example, his “About” page claims that “Newsweek calls him ‘the world’s best guinea pig,’ which he takes as a compliment.”26 I can find no such description on Newsweek’s part, though a Newsweek book review did say that “Ferriss’s willingness to be a guinea pig produces some fascinating results.”27 Similarly, Ferriss often attributes to the New York Times the quote that he is a cross between famed businessman Jack Welch and a Buddhist monk. This appears, however, to be from a 2011 profile in which Ferriss is described as “positioning himself somewhere between Jack Welch and a Buddhist monk.”28 In addition to being an author, experimentalist, and entrepreneur, he has a knack for self-promotion.

His first book, The 4-Hour Workweek, made Ferriss famous. In it, he speaks to those disenchanted with the hope of finding a dream job or getting by until retirement. Ferriss argues that by being clever, his readers can enjoy life now. The goal of the titular four-hour workweek is to “escape 9–5, live anywhere, and join the new rich,” to “free time and automate income.” This is accomplished by limiting drudgery and maximizing effectiveness.

One way to free up time is to personalize the practice of outsourcing. If companies can do it, why not us? Ferriss writes that “becoming a member of the NR [new rich] is not just about working smarter. It’s about building a system to replace yourself.”29 Such a system includes creating an absentee business and outsourcing tasks to “virtual assistants,” who can be hired for as little as a few dollars an hour in the Philippines and India. It is fitting that most of Ferriss’s chapter on outsourcing is a reprinting of A. J. Jacobs’s Esquire article on the topic; Ferriss outsourced his writing about outsourcing. This is common in Ferriss’s books, which are collages of his own experiences, recommendations, lists of resources, interviews, and excerpts from others.

With drudgery dispatched, Ferriss coaches his readers on how to be effective in what they do want to do. The four-hour approach is to deconstruct an activity into its key steps, select the critical steps, sequence them in an optimal order, and create stakes to increase accountability and motivation. For example, in The 4-Hour Workweek, he claims he won the 1999 US Chinese kickboxing championship via this method. Before weigh in, he lost twenty-eight pounds in eighteen hours through dehydration, allowing him to compete in a lighter weight class. He also exploited a technicality: a contestant who steps off the platform three times is disqualified. After rehydrating, he used his weight to push the “poor little guys,” three weight classes below him, out of the ring. He writes that he won all his matches by technical knockout—though his exploitation of the rules annoyed the judges. Ferriss committed to becoming a champion; he deconstructed the tournament (especially the rules for disqualification) and selected and sequenced the steps of water weight loss and gain. He applies this same approach in all of his work, including the thirteen episodes of his 2015 television series The Tim Ferriss Experiment, in which he attempted to quickly master the guitar, attracting women, car racing, jujitsu, parkour, and poker.

As noted, to be a successful authorpreneur, you must be an advocate for yourself. In this, Ferriss has excelled. When Wired asked its readers to vote for the biggest self-promoter of 2008, Ferriss’s fans led him to win “by a landslide.” In a New Yorker profile of Ferriss, a professional publicist praised him as “the smartest self-promoter I know.”30 In an interview a couple of years later, Ferriss disagreed with this characterization—he thought his friend and magician David Blaine was superior—but he still took it as a compliment.

The anecdote of how Ferriss determined his first book’s title and jacket design offers a good example of this savvy self-promotion. Ferriss created a Google AdWords campaign for each of the six possible titles he had in mind, including Broadband and White Sand and Millionaire Chameleon. He then bid on related searches, so that when people searched for “401k” or “language learning,” they would see one of his titles. In the course of a week, and for less than $200, Google told him that 4-Hour Work Week was the title that the most users clicked on. On the low-tech side, he printed dust cover designs and placed them on books in the new nonfiction racks at a nearby bookstore. He then sat nearby and watched which covers tended to draw the most attention. This anecdote shows moxie, and its retelling—including on Boing Boing by Doctorow—is its own form of promotion.

Ferriss displays the opportunism, self-reliance, and determination of an American self-help guru, even if he calls it “lifestyle design.” For example, he portrays the genesis of The 4-Hour Workweek as a consequence of a nervous breakdown from running his brain and performance-enhancing supplement business. Inspiration was born of desperation. Even so, his proposal for The 4-Hour Workweek was rejected by dozens of publishers, but he persevered and published three best sellers under the 4-Hour moniker. Yet the reception of the third one, The 4-Hour Chef, was a deep disappointment. Barnes & Noble refused to carry it given that it was published by Amazon. This failure then set the ground for his next success, of taking a break and experimenting with podcasting. He now reaches more people through his podcast than through his best-selling books. Ferriss capitalizes on the American fondness for bootstrap stories, and he has not yet exhausted his own. He has also taken to sourcing such stories from others; his favorite question to ask of the successful is “How has a failure set you up for a later success?”

Ferriss embodies the values of American self-help, especially the pursuit of success. However, he is different from the other life hackers in this chapter. He is not a computer geek and readily acknowledges his lack of technical chops. This contributes to his mainstream success. We will later see that when it came to hacking dating, he didn’t code a solution to the problem, he outsourced it. While others developed software to game OkCupid or created a spreadsheet for calculating romantic potential, he simply delegated the task of selecting and scheduling dates to overseas teams. Ferriss is as obsessed with experimentation and systems as anyone in this book, and he can speak about these topics to a nontechnical audience.

Life Nomadic and Superhuman

In September 2013, Tynan, a minor geek celebrity who uses his first name only, announced, “My friends and I bought an island.” The appeal in such a purchase, he observed, is that “an island is like your own little country, with complete control of everything within its borders.” Unfortunately, “cheap islands are in far away inconvenient spots, and the close islands are all crazy expensive.” Hence, the idea remained a fantasy until a friend sent him a listing for an island in eastern Canada. It turns out that many of these are “cheap AND close.” Soon after Tynan’s post, a story at Gawker declared that his achievement was the fulfillment of “one of the most-cherished fantasies of libertarian geeks everywhere.” The news was also a topic of conversation at Hacker News, a tech and entrepreneurship site, and Reddit, which has a forum dedicated to the establishment of its own self-sufficient island. The author of the Gawker article concluded: “Now that Tynan and his crew have succeeded where Reddit Island failed, I think it’s fair to say he is officially King of The Tech Geeks.”31

I would not go so far to label Tynan as “king of the tech geeks,” but he is a life hacker exemplar. Tynan is involved in most every domain I address in this book. This is a bold claim, since so many life hackers are true to type: tech savvy, travel happy, and pursuing unusual paths to success in life. Even so, my claim is substantiated by even a brief biography.

Like many life hackers, Tynan did not take school seriously. His efforts in high school were half-hearted, and this attitude persisted into college. In 2000, as a sophomore, he dropped out to pursue a different path toward wealth, friendship, and love. He took up gambling and joined a group of young men systematizing seduction.

Tynan’s gambling operation consisted of online confederates taking advantage of casino weaknesses. For example, casinos sometimes offer limited promotions that give a player a slight edge over the house, such as a 1 percent loyalty program on a slot machine. Tynan and his peers would pool their resources to extract, at scale, as much profit as possible. At the height of his operation, Tynan rented an office, hired employees, kept accounts, and paid taxes; he had to work only ten to twenty hours a week to make easy money. As a young man in his twenties, he had a nice house, a Rolex, and a Mercedes-Benz S600.

This came to an end when, in 2006, their scheme was detected and their funds were confiscated. Even if otherwise legal, casinos and banks don’t like gamblers playing loose with accounts and money. Tynan lost hundreds of thousands of dollars, which he accepted with a surprising degree of calm. He decided that despite what had been an incredibly profitable endeavor, he didn’t enjoy it anymore and that he had learned that while he liked money, he didn’t need to chase it. He hoped, instead, to focus on his other goals, to “become fully polyphasic” (i.e., sleeping only in short periods throughout the day), put fifteen pounds of lean muscle on his thin frame, become a well-known rapper, and “Find and date one incredible girl OR date several great girls.”32

This latter goal of dating amazing women speaks to the main source of Tynan’s fame, as a member of Project Hollywood. This group of pickup artists, living in Dean Martin’s former mansion, was portrayed in Neil Strauss’s best-selling 2005 book The Game.33 (Strauss is also a friend of Ferriss’s and makes appearances on his podcast and television show.) In the book’s drama-filled pages about masculine exultation and dissolution, Tynan is referred to as “Herbal”—his “rapper name,” a variation on “Ice Tea,” and appropriate to his later obsession with tea.

After the collapse of Project Hollywood, Tynan turned his attention to living with as few encumbrances as possible, to traveling the world, and to writing about it all. He traded in his house and Mercedes to pursue the Life Nomadic—the title of one of his Amazon books. For much of his adult life, his main “base” was a recreational vehicle (RV) in San Francisco—the subject of another book, The Tiniest Mansion.34 When he wants solitude, he retreats to inexpensive ocean cruises. Cheap tickets can be had on out-of-season return trips, and the food and facilities are free. There, Tynan can focus on work: writing self-published self-help books, developing a blogging platform, and most recently, developing the site Cruise Sheet, which helps others find cheap cruises. And as he still plays poker occasionally, cruise ships have plenty of weak players with money to lose.

Although he appreciates periods of solitude, relationships are key to many of Tynan’s schemes—be they gambling, seduction, or buying an island—and making friends is a topic of his book Superhuman Social Skills.35 Tynan finds his lifestyle of few possessions, frequent travel, focused work, and global friendships far preferable to an office job. When his RV was still his main base, he wrote: “I would honestly rather be, I mean, I guess I am kind of homeless when you think about it, I’m living [in an RV] at a Gas station but I’d rather be like, legitimate homeless than honestly have a hundred thousand dollar a year consulting job or something horrible like that.” This lifestyle means that he has few obligations: “you really are free, you can really do what you want to do.”36

The hacker ethos touches every facet of Tynan’s life. He is enthusiastic: “If it seems too good to be true, drop everything and check it out.”37 And he utilizes systems, whether to make money, pick up women, or automate his home. At his most developed base in Las Vegas, his smart phone wakes him, his curtains open automatically, and as he brushes his teeth, his agenda for the day is displayed on the forty-inch LCD embedded within the mirror. His home secures, vacuums, heats, and cools itself. Many of his books have the word superhuman in the title because, as he observes, “you can often achieve results that look superhuman just by setting up lots of easy systems.”38 It takes some work to set them up, but once you do, they save you time, money, and focus. Proficiency with such systems means that Tynan lives a version of masculine fantasy: one filled with “great girls,” rewarding work, and world travel.

More so than anyone else, Tynan exemplifies life hacking, even if the others portrayed here had more to do with its emergence. O’Brien coined the term, Mann and Doctorow popularized it, Trapani commercialized it, and Ferriss took it mainstream. These life hackers, and tens of thousands of others, share an ethos of individualism, rationality, systematization, and experimentation. Although this self-help’s ascendancy might appear to be like that of a tumor on a colonizing blob, it is the manifestation of a personality that thrives in the digital age. But this does not mean life is therefore easy or that hacks always work. After all, O’Brien championed hacking productivity, but his book about procrastination has yet to be written.

Notes