THUS FAR IN our exposition conclusions have been underpinned by a considerable array of first-hand data, the fruits of systematic studies begun soon after a death had occurred. In this chapter, by contrast, we have no first-hand data and are dependent, instead, on second-hand reports that refer to earlier times. Furthermore these second-hand reports not only deal with extremely complex interactions between a person who, subsequently, has become bereaved and members of his immediate family but come mostly from the parties themselves. Since such reports, as we know (see Volume II, Chapter 20), are notoriously subject to omission, suppression and falsification, they must be treated with reserve. Despite these difficulties, however, it seems that certain patterns can be discerned and that, when examined and construed in terms of the theory sketched in earlier volumes, a set of plausible, interlocking and testable hypotheses emerge.

Evidence at present available strongly suggests that adults whose mourning takes a pathological course are likely before their bereavement to have been prone to make affectional relationships of certain special, albeit contrasting, kinds. In one such group affectional relationships tend to be marked by a high degree of anxious attachment, suffused with overt or covert ambivalence. In a second and related group there is a strong disposition to engage in compulsive caregiving. People in these groups are likely to be described as nervous, overdependent, clinging or temperamental, or else as neurotic. Some of them report having had a previous breakdown in which symptoms of anxiety or depression were prominent. In a third and contrasting group there are strenuous attempts to claim emotional self-sufficiency and independence of all affectional ties; though the very intensity with which the claims are made often reveals their precarious basis.

In this chapter we describe personalities of these three kinds, noting before we start that the features of personality to which we draw attention are different to those that most clinical instruments are designed to measure (e.g. introversion-extraversion, obsessional, depressive, hysterical) and not necessarily correlated with them. We note also how limited the data are on which our generalizations rest and the many qualifications that have to be made. Consideration both of the hypotheses that have been advanced, by psychoanalysts and others, to account for the development of personalities having these characteristics, and also of the childhood experiences that presently available evidence and present theory suggest are likely to play a major part, is deferred to the next chapter.

From Freud onwards psychoanalysts have emphasized the tendency for persons who have developed a depressive disorder following a loss to have been disposed since childhood to make anxious and ambivalent relationships with those they are fond of. Freud describes such persons as combining ‘a strong fixation to the love object’ with little power of resistance to frustration and disappointment (SE 14, p. 249). Abraham (1924a) emphasizes the potential for anger: in someone prone to melancholia ‘a “frustration”, a disappointment from the side of the loved object, may at any time let loose a mighty wave of hatred which will sweep away his all too weakly rooted feelings of love’ (p. 442). ‘Even during his free intervals’, Abraham notes, the potential melancholic is ready to feel ‘disappointed, betrayed or abandoned by his love objects’ (pp. 469–70). Rado (1928ab), Fenichel (1945), Anderson (1949), and Jacobson (1943) are among many others to write in the same vein.

The studies of Parkes, both in London (Parkes 1972) and in Boston (Parkes et al. in preparation), and also of Maddison (1968) give support to these views, though both authors emphasize how seriously inadequate their data are because obtained second hand and retrospectively.

In his second meeting (at three months) with the London widows whom he interviewed, Parkes asked each of them to rate the frequency with which quarrels had occurred between them and their husbands, using a four-point scale (never, occasionally, frequently and usually). Those who reported the most quarrelling were found likely, during their first year of bereavement, to be more tense at interview, more given to guilt and self-reproach and to report more physical symptoms, and at the end of the year to be more isolated, than those who reported little or no quarrelling. They were also less likely, during the weeks after their loss, to have experienced a comforting sense of their husband’s presence. In addition Parkes found, not surprisingly, that there was a tendency for those who were most disturbed after the loss of their husband to describe having been severely disturbed by losses they had suffered earlier in their lives.

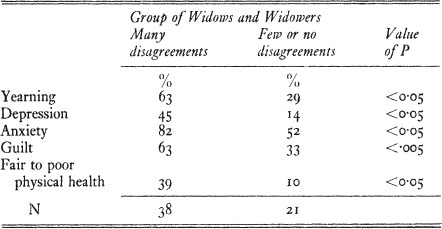

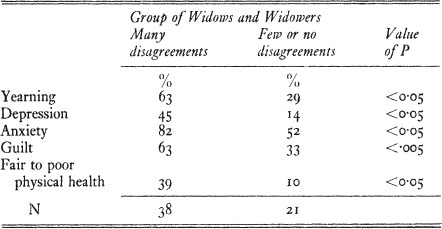

Findings of the Harvard study are comparable. In an attempt to assess the extent to which ambivalence had been present in their marriage, each widow and widower was asked a number of questions dealing with issues about which husbands and wives are apt to disagree. Both at the end of the first year and also at the follow-up two to four years after bereavement, those reporting many disagreements were doing significantly worse than were those who reported few or none. Problems described or assessed after the longer interval in a significantly higher proportion of those reporting many disagreements included: persistent yearning, depression, anxiety, guilt and poor physical health.1

Maddison (1968) reports similar findings. Among the twenty widows in his Boston sample whose mourning had taken an unfavourable course and who were willing to take part in intensive interviews there were several whose ‘marriage had shown unequivocal sado-masochistic aspects’. In addition, ‘there were several other women who gave a lengthy, sometimes virtually lifelong, history of overt neurotic symptoms or behaviour, which seemed clearly related to their subsequent deterioration’. (Because of the unreliability of his data Maddison refrains from giving figures.)

An example of a widow who had had frequent quarrels with her husband over many years and whose mourning followed a bitter and angry course was Mrs Z, one of the widows in the Harvard study.2

Mrs Z was 45 when her husband died. They had been married for twenty-six years but their relationship had never been good. Mrs Z said that she had always been very fond of her husband but felt that he had never appreciated her or expressed very much real affection. This may have been due to his jealousy of her close relationship with the children but, according to a friend who knew them both well, her ‘terrible temper’ may also have contributed. At all events there were frequent quarrels. As Mrs Z put it, ‘We were a passionate couple.’

Several years before his death Mr Z had a stroke. He had been an energetic, meticulous, and practical man and he found it particularly frustrating to be partially paralysed and dependent on his wife. He became querulous, complaining, and resentful, ‘taking it out’ on her and criticizing her unjustly. She ‘pushed him’ to do more and made plans for their future together but ‘all he gave me was criticism and abuse.’ Most painful of all, he frequently said that he hoped she would have a stroke too. She worried a great deal and complained of headaches which, she feared, might indicate that she had had a stroke. He died unexpectedly one night. When told that it was useless to continue mouth-to-mouth resuscitation since he was dead, Mrs Z would not believe it: ‘I just couldn’t take it in.’ Then she collapsed and cried profusely in an agitated state for two days.

Over the next few weeks she remained distressed and agitated and matters were made worse when the will was read and she discovered that most of his property had been left in trust. She became very bitter and resentful, saying, ‘What have I done to deserve this?’ and spent a great deal of time trying to persuade doctors and lawyers to contest the will on the grounds of her husband’s mental incapacity. When they refused to support her in this she became angry with them and, when interviewed, recited a long list of the people who, she felt, had rejected her.

Alongside this deep anger were strong feelings of guilt, but she was unable to explain these and spent much time justifying every aspect of her conduct towards her husband. She was restless and fearful, fidgeting and going from one task to another, unable to concentrate on any.

During the course of the following year she remained agitated and inclined to panic attacks. On several occasions she complained of symptoms resembling those her husband had suffered. She alienated friends and professional helpers by her aggressive attitude and demands for help.

She was given a variety of drugs by a psychiatrist and these helped a little; but thirteen months after bereavement she declared that she was no better than she had been a year previously. ‘If only I was an ordinary widow—it’s the bitterness and the will—the dreadful words. I go over it again and again thinking there must be a loop-hole.’ Yet, ‘if he could come back tomorrow I’d love him just the same’.

It seems evident from this account that it would be unfair to regard Mrs Z as wholly responsible for the chronic quarrelling that went on during this long marriage: her husband plainly made her worse. Yet it is evident that her contribution was large and that she felt that if she did not constantly stand up for herself, she would go to the wall. Referring to her battles over the will she remarked, ‘I feel if I ever accepted what he has done to me I’d be destroyed—trampled underfoot.’ As Parkes remarks, ‘Her attitude to the world betrayed her fear of just this eventuality, and because hostility provokes hostility she created a situation in which she was, in fact, repeatedly rejected by others.’ This, he suspects, had been a lifelong attitude.

Earlier in this volume (Chapter 9) it was noted that some individuals respond to loss or threat of loss by concerning themselves intensely and to an excessive degree with the welfare of others. Instead of experiencing sadness and welcoming support for themselves, they proclaim that it is someone else who is in distress and in need of the care which they then insist on bestowing. Should this pattern become established during childhood or adolescence, as we know it can be see (Chapters 12 and 21), that person is prone, throughout life, to establish affectional relationships in this mould. Thus he is inclined, first, to select someone who is handicapped or in some other sort of trouble and thenceforward to cast himself solely in the role of that person’s caregiver. Should such a person become a parent there is danger of his or her becoming excessively possessive and protective, especially as a child grows older, and also of inverting the relationship (see Volume II, Chapter 18).

Clinical accounts make it clear that some of those who, after a loss in adult life, develop chronic mourning have for many years previously exhibited compulsive caregiving, usually to a spouse or a child. Descriptions of bereaved parents who may well have conformed to this pattern are those (described by Cain and Cain 1964, and referred to in Chapter 9) who, after losing a child with whom they had had a specially intense relationship, had insisted that the ‘replacement’ child should grow up to be an exact replica of the one lost.

At least three examples of bereaved spouses who seem to conform to this pattern are described by Parkes (1972) (though he himself does not categorize them in this way). One is the case of Mr M see (Chapter 9), who was said by a member of his family to have ‘coaxed and coddled’ an anxious neurotic wife through forty-one years of marriage and who had responded to her death by directing intense reproach against himself, members of his family and others whilst simultaneously idealizing his wife. A second is the case of Mrs J see (Chapter 9) who had married a man 18 years her senior and who, having lost him from lung cancer, had exclaimed angrily nine months later, ‘Oh, Fred, why did you leave me?’ During the previous ten years or so after he had retired this pair seemed to have lived exclusively for each other. He for his part had become totally bound up with his home, his garden and his wife; and he had hated it when she went out to work. Her own role she described in the following words: ‘Ten years ago he got ill . . . and I’ve had to look after him . . . I felt I could preserve him . . . I gave into his every whim, did everything for him . . . I waited on him hand and foot.’ For the last three years during his terminal illness she had given all her time to nursing him at home.

A third example is the case of Mrs S.3

Mrs S was nearly fifty years old when interviewed in a psychiatric hospital. Her de facto husband, with whom she had lived for eleven years, had died nearly ten years earlier and ever since then she had been suffering chronic mourning. All the information came from herself.

During interview she described how she had been brought up abroad, had been a sickly child, unhappy at school, and had been tutored by her father for much of the time. Her mother, it appeared, had dominated and fussed over her; and she had grown up nervous, timid and with a conviction that she was incompetent at all practical tasks. After leaving school at seventeen she had remained at home for three years with her mother and then had lived separately though still supported by her. Before she left home she had found great satisfaction in caring for a sick child, and later her principal occupation had been that of professional child-minder and baby-sitter.

At the age of 28 she had met a man twenty years her senior who was separated from his wife. He had been invalided out of the Navy and was having difficulty in settling down in civilian life. They proceeded to live together and she changed her name to his by deed poll. To her great regret she did not conceive a child; but, despite this and despite their having been very poor, Mrs S described this period as the best in her life.

The picture she gives of their relationship seems likely to be much idealized: ‘From the first our relationship was absolutely ideal—everything—it was so right—he was so fine.’ She found, she said, she could do lots of things she had never done before: ‘I never feared anything with him. I could do new dishes . . . I didn’t get that feeling of incompetence . . . I’d absolutely found myself.’ Nevertheless, in spite of all these good features, she described how, throughout her marriage, she had been intensely anxious about the prospect of ever being separated from her husband.

For some years before his death Mr S had had a ‘smoker’s cough’ which had worried his wife; and she became seriously alarmed when he had a sudden lung haemorrhage, for which he was in hospital for six weeks. Shortly after returning home he had lapsed into a coma and had died soon afterwards.

In recounting her grief, Mrs S insisted that she had ‘never stopped crying for months’. ‘For years I could not believe it, I can hardly believe it now. Every minute of the day and night I couldn’t accept it or believe it.’ She had stayed in her room with the curtains drawn: ‘For weeks and weeks I couldn’t bear the light.’ She had tried to avoid things and places that would remind her of her loss: ‘Everywhere, walking along the street I couldn’t look out at places where we were happy together . . . I never entered the bedroom again . . . couldn’t look at animals because we both loved them so much. Couldn’t listen to the wireless.’ Nevertheless, even after nine years, she still retained in her mind a very clear picture of her husband which she was unable to shut out: ‘It goes into everything in life—everything reminds me of him.’

For a long time, she said, she used to go over in her mind all the events leading up to his death. She would agonize over minor omissions and ways in which she had failed him. Gradually, however, these preoccupations had lessened and she had tried to make a new life for herself. Yet she had found it difficult to concentrate and hard to get on with other people: ‘They’ve got homes, husbands, and children. I’m alone and they’re not.’ She had tried to escape by much listening to recorded music and reading, but this had only increased her isolation.

At some time a friendly chaplain had advised her to seek psychiatric help but she had not done so; and, although she had been treated for bowel symptoms (spastic colon) by her general practitioner, she had not divulged her real problem. Eventually she had sought help from a voluntary organization and it was the people there who had finally persuaded her to see a psychiatrist.

In this account we note many of the same features that were prominent in Mr M and Mrs J. Like them, Mrs S seems to have devoted herself exclusively to caring for her spouse who, various clues suggest, may have been a rather inadequate man. Like them, too, she responded to her spouse’s death by directing all her reproaches against herself while at the same time preserving an idealized picture of her husband and of their relationship.

In the cases of Mr M and Mrs J there are no data whatever that cast light on how or why they should have developed a disposition towards compulsive caregiving. In the case of Mrs S there is a distinct hint that a family pattern typical of school refusal may have been present during her childhood, but whether or not that is a legitimate inference must be left open. In any case we have information from other sources about the kinds of family experience that lead a person to develop along these lines, and this is considered in the next chapter as well as in Chapter 21.

Meanwhile, we note that in each of these three cases the pattern of marriage conforms closely to that described by Lindemann (in Tanner 1960, pp. 15–16) as having preceded some of the most severe examples of psychosomatic illness he had seen in bereaved people. These conditions had occurred, he states, ‘in individuals for whom the deceased [had] constituted the one significant person in the social orbit, a person who [had] mediated most of the satisfactions and provided the opportunity for a variety of role functions’, none of which were possible without him.

Looked at from one point of view the pattern of marriage of Mrs S (and also of Mr M and Mrs J), in which the relationship is idealized, and that of Mrs Z, in which there is constant quarrelling, seem poles apart. Yet, as Mattinson and Sinclair (1979) point out, they have more in common than meets the eye.

After having studied the form of interaction in a number of disturbed marriages Mattinson and Sinclair have concluded that many of them can be arranged along a continuum between two extreme patterns, which they term respectively a ‘Cat and Dog’ marriage and a ‘Babes in the Wood’ marriage. In the former the couple continually fight but do not separate. Neither trusts the other. Whereas each partner tends to make strong demands for the other’s love and support and to be angry when they are not met, each tends also to resent the demands made by the other and often to reject them angrily. Yet the couple are kept together for long periods by an intense and shared fear of loneliness. In a Babes in the Wood marriage, by contrast, all is peaceful. Each party claims he understands the other, that they are ideally suited, and perhaps even that they have achieved a perfect unity. Each clings intensely to the other.

Although overtly these two patterns are so very different, common features are not difficult to see. In both, each partner is intensely anxious lest he lose the other and so is apt to insist, or contrive, that the other gives up friends, hobbies and other outside interests. In one pattern conflict is present from the first and leads to a succession of quarrels and passionate reconciliations. In the other the very possibility of conflict is resolutely denied and each attempts to find all his satisfactions in an exclusive relationship, either by giving care to the other or by receiving it from the other, or by some combination of the roles.

In both patterns the partners may remain together for long periods of time. Nevertheless, each pattern is inherently unstable, very obviously so in the Cat and Dog marriage. In a marriage of mutual clinging the advent of a child may prove a serious threat; or one of the partners may, apparently suddenly, find the relationship stifling and withdraw. Should disruption occur, due either to desertion or death, the remaining partner is, as we have seen, acutely vulnerable and at serious risk of chronic mourning.

They are at risk too of attempting suicide and also of committing it. This emerges from a preliminary study by Parkes (in preparation) of the relatives of patients who had died in St Christopher’s Hospice.4 During a five-year period, five suicides, all by widows, were known to have occurred, four of them within five months of bereavement and the fifth two years later. The typical picture each presented was of having been ‘immature’ or clinging, of having had a very close relationship with her husband but of being on bad terms with other members of the family. In three there was a history of previous depressive disorder and/or of having been under psychiatric care. Since in the light of these findings high-risk individuals can be identified, preventive measures can be taken. These include caution in prescribing sedatives and tranquillizers, and agreement among potential caregivers as to who should undertake regular visiting.

Although it is certain that a number of those whose mourning progresses unfavourably are people who, before their loss, have been insistent on their independence of all affectional ties, our information about them is even less adequate than it is about the types of personality already considered. There are several reasons for this. First, it is in the nature of the condition that, to an external eye, their mourning should often appear to be progressing uneventfully. As a result, in all studies except those using the most sophisticated of methods, it is easy to overlook such people and to group them with those whose mourning is progressing in a genuinely favourable way. Secondly, and a source of potential error of probably far greater importance, is that individuals disposed to assert emotional self-sufficiency are precisely those who are least likely to volunteer to participate in studies of the problem. A third difficulty is that some individuals having this disposition have made such tenuous ties with parents, or a spouse or a child that, when they suffer loss, they are truly little affected by it. Among research workers whose findings we are drawing on, Parkes, Maddison and Raphael are all keenly alive to these problems; and it is for that very reason that they are so diffident about expressing firm views.

Some of the findings from Maddison’s Boston study are nevertheless of much interest. Of the twenty widows interviewed whose mourning had taken an unmistakably unfavourable course, no less than nine were believed to have had a character structure of the kind under discussion. This suggests they may form a very substantial proportion of personalities prone to pathological mourning. Yet, it must also be noted that amongst the twenty widows in the comparison group whose mourning to all appearances had proceeded favourably, there were seven such women—a proportion nearly as high as that in the bad outcome group (Maddison 1968).

Reflection on these and similar findings suggests that individuals disposed strongly to assert their self-sufficiency fall on a continuum ranging from those whose proclaimed self-sufficiency rests on a precarious basis to those in whom it is firmly organized. Examples of several patterns are already given in Chapter 9. At the more precarious end of the scale is Mrs F; at the more organized end Mr AA. Others of the cases described can be ranged at various points in the middle.

Before outlining some tentative conclusions it is necessary to note a difficulty to which Maddison (1968) and Wear (1963) amongst others have drawn attention. Occasionally a widow or widower is found who describes how various neurotic or psychosomatic symptoms from which she or he had formerly suffered have been alleviated since the spouse died. This finding is consonant with the findings of family psychiatrists which show how certain patterns of interaction can have a seriously adverse effect on the mental health of one or more of a family’s members. Some of those who have survived a spouse’s suicide and are subsequently improved in health see (Chapter 10) are other likely examples.

This finding, when taken in conjunction with other findings reported in this and previous chapters, points to a basic principle. In understanding an individual’s response to a loss it is necessary to take account not only of the structure of that individual’s personality but also of the patterns of interaction in which he was engaging with the person now lost. For a large majority of people bereavement represents a change for the worse—either to a lesser or more frequently to a greater degree. But for a minority it is a change for the better. No simple correlation between pattern of personality and form of response to loss can therefore be expected.

Tentative conclusions are as follows:

(a) A majority, probably the great majority, of those who respond to a major bereavement with disordered mourning are persons who all their lives have been prone to form affectional relationships having certain special features. Included are individuals whose attachments are insecure and anxious and also those disposed towards compulsive caregiving. Included also are individuals who, whilst protesting emotional self-sufficiency, show plainly that it is precariously based. In all such persons relationships are likely to be suffused with strong ambivalence, either overt or latent.

(b) By no means all those biased to make affectional relationships of these sorts respond to a bereavement with disordered mourning. Some of those who proclaim their self-sufficiency are in fact relatively immune to loss; whilst the course of mourning of those who make anxious attachments or who engage in compulsive caregiving is likely to be influenced in a very substantial degree by the varied conditions described in the later sections of Chapter 10.

(c) Whether or not there are also individuals prone towards disordered forms of mourning whose personalities are organized on lines different from those so far described must be left an open question.

1 The table below gives the proportions of each of the two groups who showed these features at the two- to four-year follow-up:

2 This record is taken unchanged from Parkes (1972, pp. 135–7). To avoid duplication of letters I am designating this widow Mrs Z (instead of Mrs Q as in the original). A brief reference to the case is in Chapter 10.

3 This account is a rewritten version of one given in Parkes (1972, pp. 109–10 and 125–7).

4 St Christopher’s Hospice, in South London, is designed to provide humane terminal care for the dying and also support for the bereaved.