He oft finds med’cine who his grief imparts.

SPENCER, The Faerie Queene

ALTHOUGH, THANKS TO the research of the past twenty years, a great deal is now known about why the mourning of some individuals follows a pathological course whereas that of others does not, the problem remains very difficult and a great deal more is still to be learned. Variables likely to be relevant are numerous; they tend to occur in clusters so that items within each cluster are difficult to tease apart; they interact in complex ways; and many of what appear to be the most influential are among the most controversial. All that can be attempted is to present a classification of variables, give brief indications of the likely role of each and direct attention to those thought likely to prove most powerful in determining outcome.

Variables can be classified under five heads:

In determining the course of mourning the most influential of these variables seems likely to be the personality of the bereaved, especially the way his attachment behaviour is organized and the modes of response he adopts to stressful situations. In thus postulating that some types of personality organization are more vulnerable to loss than are others, I am following a long-established psychoanalytic tradition; where the difference lies is in how the causes of vulnerability are conceived.

The effects which the many other variables have on the course of mourning are mediated inevitably through their interactions with the personality structures of the bereaved. Many of these other variables, the evidence suggests, exert great influence, either going far to facilitate healthy mourning or else going far in the opposite direction. Perhaps some of them, acting in conjunction, could lead even a relatively stable person to mourn pathologically; but more often, it seems, their effect on a stable personality is to lead mourning to be both more intense and more prolonged than it would otherwise be. Their effects on a vulnerable personality, by contrast, are far more serious. In such persons, it is clear, they not only influence the intensity and length of mourning for better or worse but they influence also and greatly the form that mourning takes, either towards a relatively healthy form or else towards one or other of the pathological variants.

Of these variables the first three are the most easily defined and can be dealt with briefly. We proceed thence to consider the social and psychological conditions which affect the bereaved around the time of the loss and during the months or years after it. The existence of some of these conditions may be independent, wholly or in large degree, of any influence that the bereaved himself may be exerting. Towards the production of others, by contrast, the bereaved may be playing some part; often it appears large. This sequence of exposition leaves to the last, indeed to the ensuing chapter, consideration of the bereaved’s personality. Reasons for postponement are, first, that features of personality are less easily defined than are other variables and, secondly, that their consideration leads on to questions of personality development and the role that family experience during childhood plays in determining individual differences, which it is argued here is of the greatest relevance to an understanding of the psychopathology of mourning.

Some of the discussions of disordered mourning to be found in the literature are concerned with losses other than those of persons, for example a house, a pet, a treasured possession or something purely symbolic. Here, however, we confine ourselves to losses of persons since they, by themselves, raise more issues than can be dealt with adequately. Furthermore, when loss of a pet has led to disordered mourning there is evidence that the relationship to the pet had become of such intense emotional significance because human relationships had ended in persistent rejection or loss.1

Almost every example of disordered mourning following loss of a person that has been reported is the result of the loss of an immediate family member—as a rule a parent (including parent substitute), spouse or child; and occasionally a sibling or a grandparent. Loss of some more distant relative or of a friend is reported extremely rarely. There are several reasons for this restriction to close kin. Some are artificial. For example, much of the research of recent years has deliberately selected for study only those individuals who have lost close kin. Another is that during routine clinical work losses of close kin, because easily defined, are more quickly and confidently identified as being of major relevance to a clinical condition than are losses of other kinds. Nevertheless, even after discounting these artificial biases, there seem solid enough reasons for believing that an overwhelming majority of cases of disordered mourning do in fact follow the loss of an immediate family member. This is so often either taken for granted or else overlooked that it is worth emphasizing.

It is of course no surprise that when disordered mourning occurs during childhood and adolescence the loss in an overwhelming majority of cases is that of a parent or parent-substitute. Perhaps it is rather more surprising that during adult life, too, such losses continue to be of some significance. In this regard, we must note, statistics are not consistent. For example, in an early study, Parkes (1964a) reviewed 94 adult patients, 31 male and 63 female, admitted to two psychiatric hospitals in London during the years 1949–51 and whose presenting illness had come on either during the last illness or within six months of the death of a parent, a spouse, a sibling or a child. Although in no less than half the cases symptoms had followed the illness or death of a parent (in 23 loss of father and in 24 loss of mother), the incidence of such loss was found to be no greater than would have been expected in the population from which the patients were drawn. In a more recent and much larger study in north-east Scotland by Birtchnell (1975b), however, in which criteria are different, a raised incidence of parent loss is found. In a series of 846 patients aged 20 and over diagnosed as depressive (278 men and 568 women) loss of a parent by death was likely to have occurred in a significantly larger number of them during a period one to five years prior to psychiatric referral than would have been expected in the population concerned.2 The incidence in men of loss of mother and in women of loss of father was in each case raised by about fifty per cent. Since the findings apply to married as well as to unmarried patients, Birtchnell concludes that marriage confers no protection.

It might be supposed that adults who respond to loss of a parent with disordered mourning will have had a close relationship with that parent; and that a majority of them therefore would be living either with the parent or else close by and seeing him or her frequently. Data so far published, however, give insufficient detail to test this possibility: such as are available refer only to those who have been residing in the same house as the parent and omit any that might be residing near by and having frequent contact, as occurs so often. Even so, of the patients in Parkes’s study whose illnesses had followed loss of a parent, no less than half had been residing with that parent for a year or longer immediately prior to the bereavement. Since in our culture only a minority of adult children live with parents, this finding, together with others reported below, support the commonsense view that disordered mourning is more likely to follow the loss of someone with whom there has been, until the loss, a close relationship, in which lives are deeply intertwined, than of someone with whom the relationship has been less close.

In this connection we note that all students of disordered mourning seem to be agreed that the relationships which precede disordered mourning tend to be exceptionally close. Yet it has proved very difficult to specify in what ways they differ from other close relationships. Much confusion is caused by the ambiguity of the term ‘dependent’. Often it is used to refer to the emotional quality of an attachment in which anxiety over the possibility of separation or loss, or of being held responsible for a separation or loss, are commonly dominant if covert features. Sometimes it refers merely to reliance on someone else to provide certain goods and services, or to fill certain social roles, perhaps without there being an attachment of any kind to the person in question. In many cases in which the term is used about a relationship it is referring to some complex mesh into which both of these components enter.

Naturally the more a bereaved person has relied on the deceased to provide goods and services, including extended social relationships, the greater is the damage the loss does to his life, and the greater the effort he has to make to reorganize his life afresh. Yet a relationship ‘dependent’ in this sense probably contributes very little to determining whether mourning takes a healthy or a pathological course. It is certainly not necessary; for example, disordered mourning can follow loss of child or loss of an elderly or invalid parent or spouse on whom the bereaved is in no way dependent in that sense of the word.

We can conclude therefore that the kind of close relationship that often precedes disordered mourning has little to do with the bereaved having had to rely on the deceased to provide goods and services or to fill social roles. As we see in the coming chapters many features of these relationships are reflections of distorted patterns of attachment and caregiving long present in both parties.

Although for reasons to be discussed shortly the number of cases reported in which disordered mourning has followed loss of child is comparatively small, students of the problem are impressed by the severity of the cases that they have seen. Lindemann (1944) remarks that ‘severe reactions seem to occur in mothers who have lost young children’. Almost the same words are used by Wretmark (1959) in his report of a study of twenty-eight bereaved psychiatric patients admitted to a mental hospital in Sweden, of whom seven were mothers and one a father. Similarly, Ablon (1971), whose study of bereavement in a Samoan community is described later in this chapter, reports that the most extreme (disturbed) grief responses were seen in two women who had lost an adopted child. One woman, who had lost a grown-up son, had developed a severe depression. The other, who had lost a school-aged daughter, treated her grandson as though he were the lost daughter.

Gorer (1965) in his survey of bereaved people in the United Kingdom interviewed six who had lost a child already adolescent or adult; and from his findings was inclined to conclude that the loss of a grown child may be ‘the most distressing and long-lasting of all griefs’. His samples are too small, however, for firm conclusions to be drawn; and, although the grieving of those he interviewed was unquestionably severe, it was not necessarily pathological.

Loss of a sibling during adult life is not frequently followed by disordered mourning. For example, in the series of 94 adult psychiatric patients studied by Parkes (1964a), although twelve had lost a sibling this is no greater than would be expected by chance. In any cases that might occur, it seems likely that the siblings would have had a special relationship, for example, that one had acted as a surrogate parent to the other. So far as I am aware, no systematic data are available by which that supposition can be checked.

In considering the relative importance of losing a parent, a spouse, a child or a sibling as causes of disordered mourning in adults we must distinguish between (a) the total number of individuals affected and (b) the incidence of disordered mourning that follows a loss of each of these kinds. This is because the death-rates for those in the roles of parent, of spouse, of child, and of sibling differ. Current death-rates in the West are highest for those in the role of father and decline progressively for those in the roles of mother, of husband, of wife and of child. (Rates for siblings are not available.) Thus, were the incidence of disordered mourning to be the same irrespective of the member of kin lost, the largest numbers of adults who suffer disordered mourning would inevitably be among those who had lost a father and the smallest number among those who had lost a child.

In fact we still have too little information about the differential incidence of disordered mourning in adults for losses of these different kinds, though Parkes’s evidence suggests that those who lose a spouse are at greatest risk. As a result of these different factors we find that in Western cultures adults suffering from disordered mourning are drawn very largely from amongst those who have lost a husband; and on a smaller scale from those who have lost a wife, a parent, or a child, with loss of sibling being comparatively rare.

Just as there are difficulties in determining the differential incidence of disordered mourning following losses of different kinds, so there are difficulties in determining the differential incidence by the age (and also the sex) of the bereaved. Most psychoanalysts are confident that incidence is higher for losses sustained during immaturity than in those sustained during adult life. Yet even for that difference no clear figures are available.

For losses sustained during adult life data are equally scarce: most of what there are refer to widows.

The findings of at least two studies have suggested that the younger a woman is when widowed the more intense the mourning and the more disturbed her health is likely to become. Thus Parkes (1964b), in his study of the visits that some 44 London widows made to their general practitioners during the first eighteen months after bereavement, found that, of the 29 who were under the age of 65 years, a larger proportion required help for emotional problems than of the fifteen who were over that age. Similarly, Maddison and Walker (1967) in their study of 132 Boston widows aged between 45 and 60 found a tendency for those in the younger half of the age-range to have a less favourable outcome twelve months after bereavement than those in the older half.

Other studies, however, have failed to find a relationship with age. For example, neither Maddison and Viola (1968) in their repeat of the Boston study in Sydney, Australia, nor Raphael (1977) in her later study in the same city found any correlation between age at bereavement and outcome. A possible explanation of the discordance is that the age-ranges of the widows in the various studies differ and that such tendency as there may be for younger widows to respond to loss more adversely than older ones affects only a particular part of the age-range. Whether that is so or not, evidence is clear that there is no age after which a person may not respond to a loss by disordered mourning. Both Parkes (1964a) and also Kay, Roth and Hopkins (1955), in their studies of psychiatric patients, have found a number whose illness was clearly related to a bereavement sustained late in life. Of 121 London patients of both sexes whose condition had developed soon after a bereavement, Parkes reports that twenty-one were aged sixty-five or over.

In terms of absolute numbers there is little doubt that there are more women who succumb to disordered mourning than there are men; but because the incidence of loss of spouse is not the same for members of the two sexes we cannot be sure that women are more vulnerable. Furthermore, it may well be that the forms taken by disordered mourning in the two sexes are different, which could lead to false conclusions. Thus it is necessary to view the following findings with caution.

There is some evidence that widows are more prone than widowers to develop conditions of anxiety and depression that lead, initially, to heavy sedation (Clayton, Desmarais and Winokur 1968) and, later, to mental hospital admission (Parkes 1964a). Yet evidence on this point from the Harvard study is equivocal see (Chapter 6). During the first year the widowers in this study seemed less affected than the widows; after two or three years, however, as great a proportion of widowers was severely disturbed as of widows. Of 17 widowers followed up, four were either markedly depressed or alcoholic or both; of 43 widows followed up, two were seriously ill and six others disturbed and disorganized.

Evidence in regard to the effects of loss of a child is equally uncertain. Whereas there is some evidence that loss of a young child is more likely to have a severe effect on a mother than on a father, in regard to loss of an older child there is reason to suspect that fathers may be just as adversely affected as mothers (e.g. Purisman and Maoz 1977).

The upshot seems to be that, whatever correlations there may be between the age and sex of the bereaved and the tendency for grief to take a pathological course, the correlations are low and probably of little importance compared to the variables yet to be considered. This perhaps is fortunate since, in our professional role of trying to understand and help bereaved people who may be in difficulty, it is their personalities and current social and psychological circumstances that we are dealing with; whereas the age and sex of the bereaved are unalterable.

The causes of a loss and the circumstances in which it occurs are enormously variable and it is no surprise that some should be of such a nature that healthy mourning is made easier and others of a kind that make it far more difficult.

First, the loss can be due to death or to desertion. Either can result in disordered mourning and it is not possible at present to say whether one is more likely to do so than the other. What follows in this chapter refers to loss by death. (Responses to loss by desertion are discussed by Marsden (1969) and Weiss (1975b).)

Next a loss can be sudden or can in some degree be predicted. There seems no doubt that a sudden unexpected death is felt as a far greater initial shock than is a predictable one (e.g. Parkes 1970a); and the Harvard study of widows and widowers under the age of 45 shows that, at least in that age group, after a sudden death not only is there a greater degree of emotional disturbance—anxiety, self-reproach, depression-but that it persists throughout the first year and on into the second and third years, and also that it leads more frequently to a pathological outcome (Glick et al. 1974; Parkes 1975a). This is a sequence long suspected by clinicians, e.g. Lindemann (1944), Lehrman (1956), Pollock (1961), Siggins (1966), Volkan (1970), and Levinson (1972). In the Harvard study, there were 21 widows who had clear forewarning of their husband’s death and 22 who had little or none.3 Of those who had reasonable forewarning only one developed a pathological condition; of those who suffered a sudden loss five did. The findings in regard to the widowers were similar.

A further finding of the Harvard study, and one not foreseen, is that two or three years after their loss not one of the twenty-two widows who had lost a husband suddenly showed any sign of remarrying in contrast to thirteen of the twenty followed up who had had forewarning. The authors suspect that this large difference in remarriage rate is due to those whose loss had been sudden having become terrified of ever again entering a situation in which they could risk a similar blow. They liken the state of mind they infer to the phobic reaction often developed by people who have experienced other sudden and devastating catastrophes, such as a hurricane or fire.

Since the spouse of a widow or widower who is still under the age of forty-five is likely to have been under fifty at death, such a loss will probably be judged by the survivors to have been untimely. The extent to which this variable, to which Krupp and Kligfeld (1962), Gorer (1965) and Maddison (1968) all draw attention, may contribute to a disordered form of mourning remains uncertain, but it clearly increases the severity of the blow and the intensity of anger aroused.

There are in fact grounds for suspecting that the severe reactions after a sudden bereavement observed so frequently in the Harvard study may occur only after deaths that are both sudden and untimely. This conclusion is reached by Parkes (1975a) after he had contrasted the clear-cut Harvard findings in young widows and widowers with the failure of the St Louis group to find any correlation between sudden bereavement and an adverse outcome (as measured at thirteen months by the presence of depressive symptoms) in the elderly group they studied (Bornstein et al. 1973).

There are other circumstances connected with a death that almost certainly make bereavement either less or more difficult to cope with, though in no case are they likely to have so great an effect as that produced by a sudden and untimely death. These other circumstances include:

(i) whether the mode of death necessitates a prolonged period of nursing by the bereaved;

(ii) whether the mode of death results in distortion or mutilation of the body;

(iii) how information about the death reaches the bereaved;

(iv) what the relations between the two parties were during the weeks and days immediately prior to the death;

(v) to whom, if anyone, responsibility seems on the face of it to be assignable.

Let us consider each.

(i) Whereas a sudden death can be a great shock to a survivor and contribute to certain kinds of psychological difficulty, prolonged disabling illness can be a great burden and so contribute to other kinds of psychological difficulty. As a result of his comparison of twenty Boston widows whose mourning had progressed unfavourably with those of a matched sample of widows who had progressed well Maddison (1968) concluded that ‘a protracted period of dying . . . may maximize pre-existing ambivalence and lead to pronounced feelings of guilt and inadequacy’. The situation is made especially difficult when the physical condition of the patient leads to intense pain, severe mutilation or other distressing features, and also when the brunt of the nursing falls on a single member of the family. In the latter type of case, in which the survivor has over a long period devoted time and attention to nursing a sick relative, she may find herself left without role or function after the loss has occurred.

(ii) Inevitably, the state of the body when last seen will affect the memories of a bereaved person either favourably or unfavourably. There are many records of bereaved people being haunted by memories or dreams of a lost person whose body was mutilated in some way; see for example Yamomoto and others (1969). In the Harvard study it was found that the widows and widowers interviewed were appreciative of the cosmetic efforts of the undertakers.

(iii) Knowledge of a death can reach bereaved people in a number of different ways. They may be present when death occurs or soon afterwards, or they may be informed of it by someone else and never see the body. Or news of it may be kept from them. There seems little doubt that the more direct the knowledge the less tendency is there for disbelief that death has occurred to persist. Disbelief is made much easier when death has occurred at a distance and also when information is conveyed by strangers. Finally, it is only natural that, when news of a death has been kept secret, as it often is from children, a belief that the dead person is still living and will return, either sooner or later, should be both vivid and persistent. There is abundant evidence that faulty or even false information at the time of the death is a major determinant of an absence of conscious grieving.

(iv) During the weeks and days immediately prior to a death relationships between the bereaved and the person who dies can range from intimate and affectionate to distant and hostile. The former give rise to comforting memories; the latter to distressing ones. Naturally the particular pattern that a relationship takes during this short period of time reflects in great part the pattern that the relationship has taken earlier; and this in its turn is a product of the personality of the bereaved interacting with that of the deceased. These are complex matters to be dealt with later; here emphasis is put on events that occur during only a very limited period.

For example, it is especially distressing when a death is preceded, perhaps by only hours or days, by a quarrel in which hard words were said. Raphael (1975) refers to the intense guilt felt by a woman who, a mere two days before her husband’s unexpected death, had had a quarrel during which she had actively considered leaving him and had felt like murdering him. Similarly, Parkes (1972, pp. 135–6) describes the persistent and bitter resentment of a widow4 whose husband had had a stroke some years before he died which had left him dependent on his wife’s ministrations. Each had criticized the other for not doing enough and, in a fit of anger, he had expressed the wish that she have a stroke too. Shortly afterwards he died suddenly. A year later she was still angrily justifying her behaviour towards him and on occasion complained of symptoms resembling his. On a much lesser scale, the mourning of the Tikopian chief for the son with whom he had quarrelled, described by Firth and referred to in Chapter 8, will be recalled.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are those deaths in which both parties are together beforehand, are able to share with each other their feelings and thoughts about the coming separation and to pay loving farewells. This is an experience that can enrich both and which, it must be remembered, can either be greatly facilitated by the attitudes and help of professional workers or else made far more difficult by them. Measures that can give help to dying people and their relatives are discussed in a new book by Parkes (in preparation).

(v) Sometimes the circumstances of a death are such that the common tendency to blame someone for it is significantly increased. For example, a spouse or a parent may have delayed calling for medical help for much longer than was wise; conversely, response to such a call may have been tardy or inadequate in the extreme. In some cases of accident or illness the person who died may have been a major contributor to it; for example, by dangerous driving or excessive smoking or drinking, or by an adamant refusal to seek medical care. In other cases it is the bereaved who may have played a significant part, either in causing an accident or perhaps by having been the person whom the one who lost his life was attempting to rescue. In all such cases there is a feeling that the death need never have occurred, and anger at the dead person, or at the self, or at third parties is greatly exacerbated.

Death by suicide is a special case in which death is felt to be unnecessary and the tendency to apportion blame is likely to be enormously increased. On the one hand, the dead person can be blamed for having deliberately deserted the bereaved; on the other, one or other of the relatives can be held responsible for having provoked his action. Very often blame is laid on close kin, especially on the surviving spouse. Others to be implicated are parents, particularly in the case of suicide by a child or adolescent; sometimes also a child is blamed by one parent for the suicide of the other. Those who mete out such blame are likely to include both relatives and neighbours; and not infrequently the surviving spouse blames him or herself, perhaps for not having done enough to prevent the suicide or even for having encouraged it. Such self-reproach may be exacerbated by allegations made by a person before he commits suicide that he is being driven to it. This may not be fanciful. Raphael and Maddison (1976) report the case of a woman who, a few weeks before her husband’s death, had separated from him telling him to go out and kill himself. This he did by using the car exhaust to gas himself.

With such high potential for blame and guilt it is hardly surprising that death by suicide may leave an appalling train of psychopathology extending not only to the immediate survivors but to their descendants as well. A number of clinicians are now alert to these pathogenic sequences and there is a growing literature, much of it brought together by Cain (1972). The articles illustrate in vivid detail the psychosocial hazards that survivors of suicide may face. Relatives and neighbours, instead of being helpful, may shun them and overtly or covertly hold them to blame. For their part the survivors, who may for long have had emotional difficulties, are tempted to challenge the verdict, to suppress or falsify what happened, to make scapegoats of others, or to devote themselves fanatically to social and political crusades in an attempt to distract themselves from what happened and to repair the damage. Alternatively, they may be beset by a nagging self-reproach and preoccupied by suicidal thoughts of their own. In the ensuing turmoil children are likely to be misinformed, enjoined to silence and blamed; in addition, they may be seen and treated as having inherited mental imbalance and so doomed to follow the suicidal parent. Further discussion of these tragic consequences is to be found in Chapter 22.

Nevertheless, as Cain is the first to realize, those seen in clinics represent only the disturbed fraction of the survivors and in order to obtain a more balanced picture we need information from a follow-up of a representative sample. A start has been made in a recent study of how the spouses of forty-four suicides fared during the five years after their bereavement undertaken by Shepherd and Barraclough (1974). Considering the number of circumstantial variables affecting direction and intensity of blame, and other factors as well, it is not surprising that those bereaved by suicide are found to be affected in extremely diverse ways.

Working in a county of southern England Shepherd and Barraclough followed up the 17 widowers and 27 widows concerned and obtained information about them all. Ages varied from eighty-one down to twenty-two, and the length of time they had been married from 49 years to a mere nine months. Almost all of them had already been interviewed once soon after the spouse’s death, as part of a study of the clinical and social precursors of suicide. When followed up some five years later it was found that ten had died, two were ill (and relatives were seen instead), and one refused further interview.

The number of deaths (10) was higher than would be expected, not only when the comparison is made with married people (expected number 4.4) but also when it is made with those widowed in other ways (6·3). The latter difference (with a likelihood of occurring by chance of about 10 per cent) is such to suggest that the death rate of those widowed by suicide may well be higher than those widowed in other ways. None of the ten deaths had been from suicide; but many of the survivors reported suicidal preoccupations.

Of the survivors 31 were interviewed by social workers. Using a questionnaire, interviews averaged about an hour but varied from twenty minutes to over three hours.

When the present psychological condition of the spouse was compared with what it was judged to have been before the suicide it was found that half were rated as better and the other half as worse (14 better, 14 worse and 3 not determined). Many of those now better off had had very difficult marriages, attributed to the personality difficulties of the spouse which included alcoholism, violence and hypochondria. Once the shocks of the suicide and the inquest were over release from such a marriage had been a relief. Of these, seven had remarried, all but one of whom had been under the age of 38 at the time of bereavement. Conversely, some of those whose condition was now worse than formerly had been happily married and had been deeply distressed by the spouse’s unexpected suicide, presumably the outcome of a sudden and severe depression in an otherwise effective personality. In one case of this kind the widow felt blamed by her husband’s relatives and had retreated into a limited social life. Nevertheless it is interesting to note that she could still take pleasure in recalling activities in which she had engaged with her husband in earlier days. Here it is necessary to distinguish between the impoverished life that may be the outcome of a bereavement and the ill effects of mourning when it takes a pathological course.

In this series men and women had similar outcomes. Contrary to some other findings, younger spouses (average age 40) did significantly better than older ones (average age 53). Another variable found to be associated with better outcome was a favourable response to the first research interview which had been conducted soon after the suicide. Of 28 who took part in both interviews, the fifteen who reported that they had been helped by the first interview also had a better outcome. There are at least three ways in which this finding could be interpreted. One is that, as the authors note, it is possible that some, having fared well later, were disposed to look back through rosy spectacles. Another is that a favourable response to such an interview, whilst real enough, occurs only in those who are destined for a reasonably good outcome in any case. A third is that the research interview was in fact a helpful experience and in some degree influenced the course of mourning for the better. The findings of studies done in Australia, to be reported in the next section, tend to support both the second and the third of these interpretations.

It happens on occasion that a bereaved person loses more than one close relative or friend either in the same catastrophe or within a period of a year or so. Others are confronted by the high risk of another such loss, for example by serious illness or by emigration of a grown child; or they may meet with some other incident felt to be stressful. Several workers, for example Maddison, both in his Boston study (Maddison 1968) and in Sydney (Maddison, Viola and Walker 1969) and Parkes in London (Parkes 1970a), have had the impression that widows subjected to such multiple crises fare worse than do those who are not. Nevertheless, although this finding would hardly be a surprising one, it has only recently been supported by firm evidence.

There is in fact a serious methodological difficulty in determining what should count as a stressor and what should not. Circularity of argument is easy. This is a problem tackled by Brown and Harris (1978a), who have adopted a method whereby the stressfulness of each event is evaluated independently of how the particular person subjected to it may have responded, or may claim to have responded. The findings of their study of life events that precede the onset of a depressive disorder, in which they used this method, support the view that persons subjected to multiple stressors are more likely to develop a disorder than are those not so subjected see (Chapter 14). In any further studies of this problem it is desirable that this method of evaluating life events should be adopted.

There is now substantial evidence that certain of the social and psychological circumstances that affect a bereaved person during the year or so after a loss can influence the course of mourning to a considerable degree. Although some such circumstances cannot be changed others can. In that fact lies hope that, with better understanding of the issues, effective help to bereaved people can be provided.

It is convenient to consider this group of variables under the following three heads, each with a pair of sub-heads:

(i) Living arrangements

(ii) Socio-economic provisions and opportunities

(iii) Beliefs and practices facilitating or impeding healthy mourning

Not surprisingly there is a tendency for widows and widowers who are living alone after bereavement to fare worse than those living with others. For example Clayton (1975) in her study of elderly people found that a year after bereavement 27 per cent of those living alone were showing symptoms of depression compared to 5 per cent of those living with others. A higher proportion also were still using hypnotics (39 per cent and 14 per cent respectively). In the case of the London widows Parkes reports trends in the same direction. He warns, however, that whilst social isolation may well contribute to depression a mourner who is depressed may also shun social exchange. Thus the causal chain may run in either direction and can readily become circular, in either a better or a worse direction.

Whereas living with close relatives who are grown up is associated with a better outcome for widows and widowers, living with younger children for whom responsibility must be taken is not. This conclusion is reached both by Parkes (1972) as a result of his London study and by Glick et al. (1974) from the findings of their Boston study. In the latter there were forty-three widows who had children to care for and seven who did not. No differences in outcome were found between the two groups, a result not difficult to explain.

In both studies it was found that responsibility for the care of children was both a comfort and a burden so that the advantages and disadvantages were evenly balanced. Those with children firmly believed that having children had given them something to live for, had kept them busy, and had been of substantial benefit to them during their first year of bereavement. Yet a closer examination of their lives showed the difficulties they had had in caring for the children single-handed and the extent to which it had restricted their opportunities to construct a new life for themselves. No less than half reported that the children had behaved in ways that were of major concern to them. Several described how presence of husband gives a woman a sense of security in dealing with her children and enables her to be tolerably consistent and how after becoming a widow they had found themselves uncertain and insecure. Some became unduly authoritarian, others too lax, and others again inclined to oscillate. Whether successful or not, almost all were unsure what would be best for the children and constantly worried lest they develop badly.

Presence of children to care for had the effect also of limiting a widow’s opportunities for developing a new life for herself. Because widows with children wished to be at home both before the children went off to school and also when they returned, and suitable part-time work was scarce, most of them postponed starting work. Furthermore, because they did not wish to leave children at home alone and baby-sitters were expensive, they declined social invitations and also were unable to attend evening classes.

No more need be said about the problems facing the widowed mother of young children. Plainly there is here a social and mental health problem of magnitude for the solution of which much thought is needed.

The social problem is how best to provide both for the widow’s welfare and also for the children’s and not to sacrifice one for the other. Adequate economic provision is obviously of importance and the same is true of accommodation. Special attention needs to be given to the provision of part-time work and also to training schemes with times consistent with caring for pre-school and school-age children.5 By providing a widow with such opportunities, economic problems are at least reduced and her chances of reconstructing her social life improved. Yet, exceedingly desirable though these provisions are, and extremely helpful though they would be to widows capable of responding to them, in and of themselves they would not influence greatly the incidence of disordered mourning since the most weighty determinants almost certainly lie elsewhere.

As we saw in Chapter 8, almost every society has its own beliefs and practices which regulate the behaviour of mourners. Since beliefs and practices vary in many ways from culture to culture and religion to religion, it might be expected that they would have an influence on the course of mourning, either promoting a healthy outcome or else, perhaps, contributing to a pathological one. A student of the problem who has expressed firm views on their importance is Gorer (1965) who was struck by the almost complete absence in contemporary Britain of any agreed ritual and guidance. Left without the support of sanctioned customs, bereaved people and their friends are bewildered and hardly know how to behave towards each other. That, he felt, could only contribute to unhappiness and pathology.

Another social anthropologist who in recent years has expressed a similar view is Ablon (1971), who has studied a close-knit Samoan community resident in California. In this community almost everyone lives within an extended family and a key value is reciprocity, especially of support in time of crisis. Thus, following a death, there is an immediate rallying of kin and friends who, with efficiency born of established practice, take the burdens of making decisions and arrangements from the shoulders of spouse, or parents or children, console the grieving and care for orphans. Ritual includes both Christian ceremonies and also traditional exchanges of goods and donations, in all of which family network and mutual support are emphasized and prominent. In this type of community, Ablon believes, disabling grief syndromes hardly occur. Nevertheless, although their incidence may well be reduced, her evidence shows that in certain circumstances they still do occur.

In her study Ablon made follow-up visits to a number of families whose members had suffered bereavement or major injury in a fire which had occurred during a Samoan dance five years earlier, and which had resulted in 17 deaths and many injured. Of about sixty families affected she visited 18. From the information she was able to obtain, she formed the impression that the Samoans, both as individuals and as family groups, had ‘absorbed the disaster amazingly well’. She instances three young widows who had all remarried and were living full and active lives; and a fourth, in her forties and with six children, who had built up a successful business. Yet Ablon’s sample was small and included, as well as those doing well, the two women who had lost adopted children and whose conditions were unmistakably those of disordered mourning. These findings call in question the theory that cultural practices alone can account for the course that mourning takes in different individuals.

Evidence from other studies raises the same issue. For example, neither in Parkes’s London study nor in the Harvard study did the religious affiliation of the widows and widowers bear any clear relation to the pattern of outcome.

Reflection on the ambiguity of these findings suggests that the cultural variable is too crude a one for understanding the influence of beliefs and practices on the course of mourning. For example, although the negative findings in London and Boston may have been due to the religious sub-samples in each study having been too small to yield significant differences, it is also possible that within each religious group, and also within the non-affiliated, variations of belief and practice were as great as they were between groups. That this may be the explanation is supported by Ablon’s finding that both the two Samoan women whose mourning had taken a pathological course were culturally atypical in regard to family life. Though divorce was not common among Samoans of their age, both had been divorced and were in their second marriages. Each had only one other child and neither lived in an extended family. These exceptions to Ablon’s thesis may therefore point to where the rule lies.

When we turn to consider influences that are operating at an intimate personal level within the broader culture we find strong evidence that families, friends and others play a leading part either in assisting the mourning process or in hindering it. This is a variable to which clinicians have for long drawn attention (e.g. Klein 1940; Paul 1966) and on which Maddison, who worked for a time with Caplan at Harvard but whose work has been mainly in Australia, has focused attention.

Under Maddison’s leadership three studies have been carried out aimed to elucidate the influence on the course of mourning of relatives, friends and other people. The first was conducted in Boston (Maddison and Walker 1967; Maddison 1968), the second and third in Sydney (Maddison, Viola and Walker 1969; Raphael 1976, 1977). The first two were retrospective, and so have deficiencies; the third which was prospective makes good many of them.

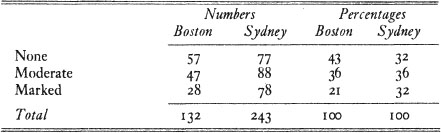

Both of the retrospective studies were carried out in the same way. The first step was to send questionnaires seeking information about physical and mental health to a large sample of widows in Boston (132) and in Sydney (243) thirteen months after their loss see (Chapter 6 for details). The 57 questions referring to health were so structured that the only scoring items were those which recorded complaints that were either new or had been substantially more troublesome since the loss. On the basis of their answers, together with a check by telephone, widows in each study were divided into three groups: those whose health record appeared favourable, those whose record indicated a substantial deterioration in health, and an intermediate group which was not further considered. The numbers and percentages of widows in each group are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2 Deterioration in health

The second stage of each study began by selecting sub-samples of widows (a) with favourable outcome and (b) with unfavourable outcome, matched as closely as possible on all social and personal variables on which data were available. In the Boston study 20 pairs of widows were identified as willing to take part in further enquiry; in the Sydney study 22 good-outcome widows were matched with 19 bad-outcome.

All subjects were seen, usually in their own homes, in a long semi-structured interview which lasted on average two hours. The aims were to check on the validity of the questionnaire (which proved a good index of how a person is coping with the emotional problems of bereavement) and, more especially, to investigate who had been available to each widow during the bereavement crisis and whether she had found them helpful, unhelpful or neither. Further questions were directed to finding out whether she had found it easy or difficult to express her feelings to each person mentioned, whether or not he had encouraged her to dwell on the past, whether he had been eager to direct her attention to problems of the present and future, and whether he had offered practical help. Since the object of the enquiry was to find out only how the widows themselves recalled their dealings with others, no attempt was made to check how their accounts might have tallied with those of the people with whom they had been in contact.

First, it was found in both cities that all the widows, irrespective of outcome, tended to report a good deal of helpful interaction. In each city, nevertheless, there was a marked difference between widows with a good outcome and those with a bad outcome in their reports of unhelpful interactions. Whereas those with a good outcome reported having met with few or no unhelpful interactions, those with a bad outcome complained that, intead of being allowed to express their grief and anger and to talk about their dead husband and the past, some of the people they had met had made expression of feeling more difficult. For example, someone might have insisted that she pull herself together and control herself, that in any case she was not the only one to suffer, that weeping does no good and that she would be wise to face the problems of the future rather than dwell unproductively on the past. By contrast, a widow with a good outcome would report how at least one person with whom she had been in contact had made it easy for her to cry and to express the intensity of her feelings; and would describe what a relief it had been to be able to talk freely and at length about past days with her husband and the circumstances of his death. Irrespective of outcome no widow had found discussion of future plans at all helpful during the early months.6

The individuals with whom a widow had been in contact had usually included both relatives and professionals, for example the medicals who had cared for her husband and also her own doctor, a minister of religion and a funeral director. In some cases a neighbour or shopkeeper had played a part. Some widows reported how they had received much more understanding of their feelings from such local acquaintances than they had from relatives or professionals who in some cases, they said, had been hostile to any expression of grief. In some cases the husband’s mother had created substantial difficulties either by claiming or implying that the widow’s loss was of less consequence than her own or else by blaming the widow for having taken insufficient care of her husband or for some comparable shortcoming.

A person of obvious importance during bereavement is a widow’s own mother, should she still be alive and available. Some particulars are given for the Boston widows. Since a majority of them were middle-aged, in only twelve of the forty was the mother available. Where the relationship had long been a mutually gratifying one the mother’s support seemed to have been invaluable and progress was good. Where, by contrast, relationships had been difficult mourning was impeded: all four widows who described their mothers as having been unhelpful proceeded to a bad outcome. Though the sample is small, a one-to-one correlation between a widow’s relationship with her mother and the outcome of her mourning is striking and unlikely to be due to chance. Its relevance to an understanding of persons disposed towards a healthy or a pathological response to loss respectively cannot be overemphasized and is considered further in later chapters.

There is, of course, more than one way of interpreting Maddison’s findings—as there was in the case of widows and widowers whose spouses had committed suicide and who referred to the first research interview as having been helpful. Here again a widow may retrospectively have distorted her experiences; or she may have attributed to relatives and others her own difficulties in expressing grief; or the behaviour of those with whom she had come into contact may indeed have contributed significantly to her problems. In any one case two or even all three of these processes might have been at work. Nevertheless Maddison himself, whilst recognizing the complexities of the data, tends to favour the third interpretation, namely, that the experiences reported are both real and influential in determining outcome. This interpretation is strongly supported by the findings of a prospective study carried out subsequently in Maddison’s department in Sydney by Raphael.

Utilizing methods similar to those used in Maddison’s earlier studies and drawing both on his findings and on some pilot work of her own, Raphael (1977) set out to test the efficacy of therapeutic intervention when given to widows whose mourning seemed likely to progress badly. Procedure was as follows:

Criteria for the sample were to include any widow under the age of sixty who had been living with her husband and who could be contacted within seven weeks of bereavement and was willing to participate. Such widows, who were first contacted when they applied for a pension, were invited by the clerk to take part in a study being conducted in the Faculty of Medicine of Sydney University and were provided with a card to post there should they be willing to do so. Altogether nearly two hundred volunteers were enlisted. For administrative reasons it proved impossible, unfortunately, to discover how many of the widows approached decided not to participate and how they might have differed from those who volunteered. The latter were visited in their own homes by an experienced social worker who first explained the project and the proposed procedure in order to obtain consent and then engaged the widow in a long interview.

Altogether 194 widows agreed to participate. Ages ranged from 21 to 59 years with a mean of 46; 119 had children aged 16 or younger. Since only those who believed themselves eligible for a pension were contacted, three-quarters or more were from the lower half of the socio-economic scale.

The purpose of the long interview was to obtain enough information about the widow, her marriage, the circumstances of her loss and her experiences since, to enable a prediction to be made as to ‘whether her mourning was likely to proceed favourably or unfavourably. The principal criterion for predicting an unfavourable outcome was the frequent reporting by a widow of unhelpful interventions by relatives and others and of needs that had gone unmet. The following are examples of the experiences they reported:

‘When I wanted to talk about the past, I was told I should forget about it, put it out of my mind.’

‘I wanted to talk about how angry I was but they said I shouldn’t be angry . . .’

‘When I tried to say how guilty I felt, I was told not to be guilty, that I’d done everything that I should, but they did not really know.’

A widow whose normal protest and sadness had been treated with large quantities of tranquillizers remarked—

‘I felt bad because I couldn’t weep: it was as though I was in a straitjacket . . .’

Among additional criteria used to predict an unfavourable outcome were exposure to multiple crises and a marriage judged to have taken a pathological form. Details are given in a footnote.7

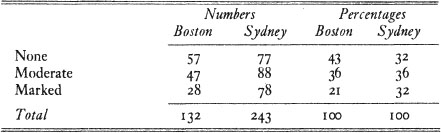

On the basis of the information obtained, widows were allocated to one of two groups: Group A those whose outcome was predicted as good and Group B those whose outcome was predicted as bad. No differences were found between widows in the two groups in regard to age, number of children or socio-economic class. Those in Group B were then allocated at random to one of two sub-groups: B1, those who would be offered counselling and B2 those who would not. Numbers falling into the three groups were:

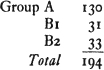

Thirteen months after bereavement all widows were invited to complete the same health questionnaire that Maddison had used in his earlier studies. Scored by the same methods as formerly, it was then possible to determine what the outcome had been for widows in each of the three groups. Those whose health had deteriorated substantially were contrasted with the remainder. (In 16 cases follow-up was not practicable so that the three groups were reduced in numbers to 122, 27 and 29 respectively.) Results are summarized in Table 3.

When the outcomes of those in the two groups not given counselling (Groups A and B2) are compared it is found that the predictions were reasonably accurate and very much better than chance. In addition, when the outcomes of those in Group B1 (with an unfavourable initial prediction but given counselling) are compared with the outcomes of the other two groups it is clear, first, that the outcomes of Group B1 are virtually as good as they are for those in Group A (whose outcomes were predicted as good from the start) and, secondly, that the outcomes of Group B1 are significantly better than those of Group B2 whose predicted outcomes were also unfavourable but who received no counselling. A check on the possibility that the latter result was due to the widows in Group B1 having differed in some significant way from those in Group B2 showed that there were in fact no relevant differences between the groups.

TABLE 3 Outcome 13 months after bereavement

Widows in the counselled Group B1 showed a lower incidence of depression, anxiety, excessive alcohol intake and certain psychosomatic symptoms than did widows in the non-counselled Group B2.

The conclusion that counselling is in some degree effective is strongly supported by internal evidence derived from a detailed study of the 27 widows in the counselled group, 21 of whom did well and six of whom did badly. First, it was found that those who made best use of the counselling sessions had a significantly better outcome than those of the group who did not; thus, of the six who went on to a bad outcome four had given up the sessions early. Secondly, there was a high correlation between those who were judged by an independent rater to have proceeded successfully towards healthy mourning during the weeks of counselling and a favourable outcome at thirteen months.

Although these findings point clearly to the efficacy of the techniques of counselling used, it should be borne in mind that all the subjects were volunteers. Whether or not the same techniques would have been efficacious with those who did not volunteer and who in the event went on to a bad outcome remains unknown.

A second conclusion is that the criteria used in the study for predicting outcome are valid, at least within certain limits.8 Yet here again qualifications are necessary. Amongst the 122 volunteers predicted to have a good outcome, one in five nevertheless progressed badly. Furthermore, it is possible that some of the others whose condition thirteen months after bereavement was reported to be good (as predicted) may have been individuals who were inhibiting grief and so would have been prone to break down later. Against this possibility, however, is Raphael’s belief (personal communication) that few such individuals were likely among the volunteers, because it is in the nature of the condition that they would avoid participating in any enquiry which might endanger their defences.

Let us turn now to the techniques used by Raphael in her project. They derive from techniques pioneered by Caplan (1964) for use in any form of crisis intervention.

Within one week of a widow being interviewed and assessed as likely to have a bad outcome and having been allocated to the intervention group, the counsellor (Dr Raphael) called on the widow or made telephone contact. Linking her intervention to the problems the widow had described in the assessment interview, assistance was offered. If accepted, as it was by the majority, a further call was arranged. All further sessions took place within the first three months of bereavement and were confined, therefore, to a period of about six weeks. Almost all took place in the widow’s own house and usually lasted two hours or longer. When appropriate, children, other members of the family and neighbours were included. The number and frequency of sessions varied according to need and acceptability but were never more frequent than weekly.9 In every case the aim of a session was to facilitate the expression of active grieving—sadness, yearning, anxiety, anger and guilt.

Since the technique adopted by Raphael is similar to those now widely used in counselling the bereaved, it is described in a form that has general application.

As a first step it is useful to encourage a widow to talk freely and at length about the circumstances leading to her husband’s death and her experiences after it. Later she can be encouraged to talk about her husband as a person, starting perhaps from the time they first met and proceeding thence through their married life together, with all its ups and downs. Showing of photographs and other keepsakes, which is natural enough in the home setting, is welcomed. So also is the expression of feeling that has its origin in other and previous losses. During such sessions a tendency to idealize usually gives way to more realistic appraisal, situations that have aroused anger or guilt can be examined and perhaps reassessed, the pain and anxiety of loss given recognition. Whenever yearning and sadness seem to be inhibited or anger and guilt misdirected, appropriate questions may be raised. By thus giving professional help early in the mourning process it is hoped to facilitate its progress along healthy lines and to prevent either a massive inhibition or a state of chronic mourning becoming established.

The first point to be noted in considering Raphael’s results is that the social interchanges encouraged by the technique adopted and that proved efficacious were exactly those that the widows had complained had not been provided or permitted by the relatives and others they had met. This finding strongly supports the view that a major variable in determining outcome is the response a widow receives from relatives, professional personnel and others when she begins to express her feeling.

The second point is a more general one. When expressed in terms of the theory of defence sketched in Chapter 4, a principal characteristic of the technique employed is to provide conditions in which the bereaved person is enabled, indeed encouraged, to process repeatedly and completely a great deal of extremely important information that hitherto was being excluded. In thus laying emphasis on information processing, I am drawing attention to an aspect of the technique that tends to be overlooked by theorists. For it is only when the detailed circumstances of the loss and the intimate particulars of the previous relationship, and of past relationships, are dwelt on in consciousness that the related emotions are not only aroused and experienced but become directed towards the persons and connected with the situations that originally aroused them.10

With these findings in mind it becomes possible to consider afresh the question of what types of personality are prone to develop a disordered form of mourning. It becomes possible, too, to propose hypotheses regarding the family experiences they are likely to have had during childhood and adolescence and, thence, to frame a theory of the processes that underlie disordered mourning.

1 Keddie (1977) and Rynearson (1979) each report three cases, all of women. In one the patient when aged three years had become deeply attached to a puppy given her soon after losing both her parents due to a breakup of the marriage. In three the patient had suffered repeated rejection by her mother and had turned to a cat or a dog instead. In two the patient seems to have regarded the pet as taking the place of a child, in one of a son who died in infancy and in the other following an early hysterectomy.

2 Whenever a comparison is made between the incidence of a potential pathogen in a group of patients and the incidence in the whole population from which the patients are drawn, it is likely that the difference between the two will be underestimated. This is because undeclared cases of the condition may be present in the comparison group.

3 The criteria for short forewarning were less than two weeks’ warning that the spouse’s condition was likely to prove fatal and/or less than three days’ warning that death was imminent.

4 Parkes designates this widow as Mrs Q, but to avoid duplication of letters I am describing her as Mrs Z. A fuller account of Mrs Z’s marriage is given in Chapter 11.

5 In the U.K. these problems were considered by the Royal Commission on One Parent Families whose report makes many recommendations (Finer Report, H.M.S.O. 1974).

6 A difference in the findings between the cities was that in Boston but not in Sydney widows with a had outcome felt that many of their emotional needs had gone unmet; these were especially their need for encouragement and understanding to help them express grief and anger and their need for opportunities to talk about their bereavement at length and in detail. By contrast, those with a good outcome expressed no such unmet needs. (Note: In Volume I of this work, Chapter 8, it is pointed out that the term ‘need’ is ambiguous and is to be avoided. In the context in which Maddison uses the term, it is synonymous with desire.)

7 Assessment interviews were conducted in as spontaneous and open-ended a manner as possible and usually lasted several hours. An interview schedule was used to cover six types of information: (a) demographic, (b) a description of the causes and circumstances of the death leading to a discussion of feelings aroused by it, (c) a description of the marriage, (d) the occurrence of concurrent bereavements and other major life changes, (e) the extent to which relatives, professional personnel and others had been found supportive or not, (f) completion of a checklist of such interchanges which can be scored as having been present or absent, and, if present, whether found helpful, unhelpful or neither, and, if absent, whether an interchange of that kind had been desired or not. Since most widows were very willing to discuss their experiences, most of this information was obtained spontaneously. When it was not, the interviewer raised relevant points, remarking that there were things which other women had experienced following bereavement and querying whether they might also apply to the widow being interviewed.

Outcome was predicted as likely to be unfavourable when interview data showed that one or more of the following criteria were met:

Criterion 1 was derived from the answers scored on the check list used during the assessment interview. The reliability of judgements made when applying criteria 2, 3 and 4 was tested and proved satisfactory for judgements of the occurrence of additional stressors and also of a pathological form of marriage. (Correlations of the judgements of three independent judges for these criteria were 95 per cent.) Reliability of judgements for mode of death was not satisfactory however (correlation 65 per cent).

Rather more than half those predicted as likely to have a bad outcome were selected by applying criterion 1

8 Of the four criteria used the most highly predictive of bad outcome was criterion 1 (ten or more examples of a widow having felt either that interchanges had been unhelpful or that her needs had gone unmet). Criterion 1 was also related to the efficacy of counselling: widows whose bad outcome had been predicted on the basis of that criterion proved to be those most helped.

9 For the 31 widows who were offered counselling, interviews ranged from one to eight in number, with four as the most frequent. Of the 27 who were also followed up, ten had been interviewed at least once with dependent children present, and in several cases with other relatives or neighbours as well. With a further two subjects relatives or neighbours had been present on at least one occasion (personal communication).

10 A similar though more active technique, derived from the pioneer work of Paul and Grosser (1965) and applying the same principles, has been found effective in helping patients referred to a psychiatric clinic, presenting with a variety of clinical syndromes, whose illness had developed after a bereavement (Lieberman 1978). In this series as in many similar cases the symptoms had not usually been connected to the loss either by the referrer or by the initial psychiatric interviewer. See also the therapeutic technique used by Sachar et al. (1968) with a small group of depressed patients.