The affect corresponding to melancholia is mourning or grief—that is, longing for something that is lost.

SIGMUND FREUD1

IN THIS CHAPTER, in which I indicate how I approach the large and controversial field of depressive disorder,2 we broaden the canvas temporarily to take account of losses due to causes other than death.

First, let us consider in what ways a person who is sad, and perhaps temporarily depressed, differs psychologically from someone who is chronically depressed or perhaps diagnosed as suffering from a depressive disorder.

Sadness is a normal and healthy response to any misfortune. Most, if not all, more intense episodes of sadness are elicited by the loss, or expected loss, either of a loved person or else of familiar and loved places or of social roles. A sad person knows who (or what) he has lost and yearns for his (or its) return. Furthermore, he is likely to turn for help and comfort to some trusted companion and somewhere in his mind to believe that with time and assistance he will be able to re-establish himself, if only in some small measure. Despite great sadness hope may still be present. Should a sad person find no one helpful to whom he can turn, his hope will surely diminish; but it does not necessarily disappear. To re-establish himself entirely by his own efforts will be far more difficult; but it may not be impossible. His sense of competence and personal worth remains intact.

Even so, there may well be times when he feels depressed. In an earlier paper (Bowlby 1961b) I suggested that depression as a mood that most people experience on occasion is an inevitable accompaniment of any state in which behaviour becomes disorganized, as it is likely to do after a loss: ‘So long as there is active interchange between ourselves and the external world, either in thought or action, our subjective experience is not one of depression: hope, fear, anger, satisfaction, frustration, or any combination of these may be experienced. It is when interchange has ceased that depression occurs [and it continues] until such time as new patterns of interchange have become organized towards a new object or goal . . .’

Such disorganization and the mood of depression that goes with it, though painful and perhaps bewildering, is none the less potentially adaptive. For until the patterns of behaviour that are organized for interactions that are no longer possible have been dismantled it is not possible for new patterns, organized for new interactions, to be built up. It is characteristic of the mentally healthy person that he can bear with this phase of depression and disorganization and emerge from it after not too long a time with behaviour, thought and feeling beginning to be reorganized for interactions of a new sort. Here again his sense of competence and personal worth remains intact.

What accounts then for the more or less intense degrees of hopelessness and helplessness that, as Bibring (1953) pointed out many years ago, are characteristic of depressive disorders and for the sufferers so often feeling abandoned, unwanted and unlovable, as Beck (1967) among others has emphasized? As a result of this study I suggest a number of factors any one or any combination of which may be present.

Seligman (1973) draws attention to the ways in which a person, having frequently failed to solve certain problems, thereafter feels helpless and, even when confronted with a problem that is well within his capabilities, is liable to make no attempt to tackle it. Should he then attempt it and succeed, moreover, he is still liable to discount his success as mere chance. This state of mind, which Seligman aptly terms ‘learned helplessness’, is responsible, he suggests, for the helplessness present in depressive disorders. The theory he proposes is highly compatible with that advanced here.

In most forms of depressive disorder, including that of chronic mourning, the principal issue about which a person feels helpless is his ability to make and to maintain affectional relationships. The feeling of being helpless in these particular regards can be attributed, I believe, to the experiences he has had in his family of origin. These experiences, which are likely to have continued well into adolescence, are postulated to have been of one, or some combination, of three interrelated kinds:

(a) He is likely to have had the bitter experience of never having attained a stable and secure relationship with his parents despite having made repeated efforts to do so, including having done his utmost to fulfil their demands and perhaps also the unrealistic expectations they may have had of him. These childhood experiences result in his developing a strong bias to interpret any loss he may later suffer as yet another of his failures to make or maintain a stable affectional relationship.

(b) He may have been told repeatedly how unlovable, and/or how inadequate, and/or how incompetent he is.3 Were he to have had these experiences they would result in his developing a model of himself as unlovable and unwanted, and a model of attachment figures as likely to be unavailable, or rejecting, or punitive. Whenever such a person suffers adversity, therefore, so far from expecting others to be helpful he expects them to be hostile and rejecting.

(c) He is more likely than others to have experienced actual loss of a parent during childhood (see later this chapter) with consequences to himself that, however disagreeable they might have been, he was impotent to change. Such experiences would confirm him in the belief that any effort he might make to remedy his situation would be doomed to failure.

On this view it is predicted that the particular pattern of depressive disorder that a person develops will turn on the particular pattern of childhood experiences he has had, and also on the nature and circumstances of the adverse event he has recently experienced.

Admittedly, these views are based on fragmentary evidence and are still conjectural. Yet they provide plausible and testable explanations for why someone severely depressed should feel not only sad and lonely, as might others in similar circumstances, but also unwanted, unlovable and helpless. They provide a plausible explanation also for why such persons are so often uneasy about or unresponsive to offers of help.

Exposure to experiences of the kinds postulated during childhood would also help explain why in depressive-prone individuals there should be so strong a tendency for the sadness, yearning and perhaps anger aroused by a loss to become disconnected from the situation that aroused them. Whereas, for example, in healthy mourning a bereaved person is much occupied thinking about the person who has died and perhaps of the pain he may have suffered and the frustration of his hopes, and also about why the loss should have occurred and how it might have been prevented, a person prone to depresive disorder may quickly turn his attention elsewhere—not as a temporary relief but as a permanent diversion. Preoccupation with the sufferings of the self, to the exclusion of all else, is one such diversion and, when adopted, may become deeply entrenched. The case of Mrs QQ, the thirty-year-old mother of a leukaemic child reported by Wolff et al. (1964b) and already described in Chapter 9, provides an example. Although she was frequently anxious, agitated and tearful, she successfully avoided discussion of her son’s deteriorating condition by endless talk about how upset she was and how she could not stand her feelings any longer. Other authors to draw attention to the diversionary or defensive function of self-centred ruminations in patients suffering from depressive disorders are Sachar et al. (1968) and Smith (1971).

As discussed in Chapter 4, a disconnection of response from situation can be of very varying degrees and take several different forms. One of the more intractable forms, I suspect, results from a parent implicitly or explicitly forbidding a child, perhaps under threat of sanctions, to consider any mode of construing either his parents or himself in ways other than those directed by the parent. Not only is the child, and later the adolescent and adult, unable then to reappraise or modify his representational models of parent or self, but he is forbidden also to communicate to others any information or ideas he may have that would present his parents in a less favourable light and himself in a more favourable one.

In general, it seems likely, the more persistent the disorder from which a person suffers the greater is the degree of disconnection present and the more complete is the ban he feels against reappraising his models.

Brief reference has been made to some of the empirical findings reported by Aaron Beck as a result of his extensive and systematic study of patients suffering from depression (Beck 1967; Beck and Rush 1978; Kovacs and Beck 1977). It may therefore be useful to say a word about the theory he has formulated to account for his findings and how it relates to the theory advanced here.

Instead of adopting one of the traditional views that depressive disorder is ‘a primary severe disorder of mood with resultant disturbance of thought and behaviour’ (to quote the definition given in the 1952 and 1968 editions of the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association), or is the consequence of aggression turned inwards as Freud proposed, Beck presents evidence that a patient’s dejected mood is the natural consequence of how he thinks about himself, how he thinks about the world, and how he thinks about his future. This leads Beck to formulate a cognitive theory of depressive disorders, a theory cast in the same mould as the theory of cognitive biases proposed here. Both formulations postulate that depressive-prone individuals possess cognitive schemas having certain unusual but characteristic features which result in their construing events in their lives in the idiosyncratic ways they do.

Where the two formulations differ is that, whilst one attempts to account for the development of such schemas by postulating that those who develop them have been exposed to certain characteristic types of experience during their childhood, the other offers no explanation. Although, like many clinicians, Beck assumes that experiences of childhood play some part in the development of these schemas, he pursues the matter no further, remarking with justice that research in this field is fraught with difficulty.

In summary, it can be said that Beck’s data are explicable by the theory advanced here, and also that, within the limits it sets itself, his theory is compatible with mine. Where the two theories differ is that Beck’s attempts much less.

Not infrequently the state of mind of someone severely depressed is described, or explained, in terms of loss of self-esteem. This is a concept I believe inadequate to the burden placed upon it. For it fails to make manifest that the low self-evaluation referred to is the result of one or more positively adverse self-judgements, such as that the self is incapable of changing the situation for the better, and/or is responsible for the situation in question, and/or is intrinsically unlovable and thus permanently incapable of making or maintaining any affectional bonds. Since the term ‘low self-esteem’ carries none of these meanings, it is not employed here.

Ever since Freud published his ‘Mourning and Melancholia’ the questions of the extent to which depressive disorders are related to loss and of the proportion of cases that can properly be regarded as distorted versions of mourning have remained unanswered. Nor can they be answered by proceeding as we have so far. For to answer them requires an approach different to that adopted. Instead of proceeding prospectively as we have been doing, starting with a loss and then considering its consequences, it is necessary to start with representative groups of individuals suffering from depressive disorders and then determine, retrospectively, what we know of their causes.

As it happens, the findings of a major study of this very sort by George Brown, a British sociologist, have been published during the past decade and these go some way to providing the answers we seek. His recent book with Tirril Harris, The Social Origins of Depression (1978a), gives a comprehensive account of the enquiry and its findings and also particulars of earlier publications.

Brown and his colleagues set out to study the parts played by social events of emotionally significant kinds in the aetiology of depressive disorders. In doing so they took account not only of recent events and current conditions but also of certain classes of earlier events. In what follows we discuss the influence of two only of the many variables Brown took into account. These are, first, the role of recent life events and, secondly, that of childhood loss. Keenly aware that these are fields long bedevilled by difficult problems of methodology Brown designed his project with exceptional care.

Some of the problems he and his colleagues sought to solve were those of sampling. To meet them they took steps to ensure both that their sample of individuals suffering from depressive disorders was reasonably representative of all those afflicted and not confined to those in psychiatric care, and also that their comparison group of healthy individuals was free of undeclared patients.

Another problem to which they gave much attention was that of deciding what is to be counted as an event of emotional significance to the person in question. Were the decision left entirely to the person there is danger of circular argument, for any event that he claims has caused him stress will be counted as stressful; and the more readily distressed a person is prone to be the more numerous the stressful events that he will be scored. Conversely, for reasons already discussed, a disturbed person may fail to mention events that may later be found to be of high relevance to his distress and may either state that he has no idea what might have upset him or else blame for his troubles events later found to be of little consequence. Even so, it must be recognized that although the person in distress cannot be taken as the final arbiter in the matter, unless attention is paid to the detailed circumstances in which he is living the meaning that an event has for him will be missed. For example, whether the birth of a baby is an occasion for great joy, for great anxiety or for great misery depends on the parent’s circumstances.

Sampling. During their enquiry, conducted in a South London borough, Brown and Harris studied two main groups of women, a patient group and a community group. The patient group comprised 114 women, aged between 18 and 65, who were diagnosed as suffering from one or another form and degree of depressive disorder of recent onset and were receiving psychiatric treatment, either as in-patients or as out-patients. The community group comprised a random sample of 458 women in the same age-range as the patients and living in the same inner-London borough. From amongst its members several sub-samples were drawn.

In their investigation of the community sample a first task was to identify those women who, though not in psychiatric care, were none the less suffering from psychiatric disorder. This was done by a sociologist, supported by a research psychiatrist, interviewing every woman using a somewhat abbreviated version of the form of clinical examination that the psychiatrist used when interviewing members of the patient group (namely, the Present State Examination devised by Wing et al. 1974). Drawing on the results of this examination and any other information available, a judgement was made on the mental health of each woman in the sample. Those who had symptoms of a severity sufficient to merit psychiatric attention, according to the standards generally accepted in the United Kingdom, were classified as ‘cases’. Those who had symptoms but the severity of which was below criterion were classified as ‘borderline cases’. Central to the judgements was the use of anchoring examples for both cases and borderline cases.

Of the 458 women in the community sample, 76 were classified as cases and 87 as borderline cases, leaving 295 as relatively symptom free. For such of the findings as are reported here the borderline cases have been pooled with the symptom free, making a sub-sample of 382 women available as a comparison group.

The next task was to identify the date of onset of symptoms in the 76 women classified as cases. In about half (39) the symptoms had been present for twelve months or longer. These are termed chronic cases. In the remaining 37, onset was judged to have been within a year of interview; these are termed onset cases.4

The outcome of this preliminary work was that four groups of women had been identified, the 114 in the patient group, the 39 in the chronic and the 37 in the onset case groups, and the 382 women in the community group classified as normal or borderline.

For that part of the enquiry aimed to determine the role of recent life events the group of chronic cases was excluded and the enquiry confined to the other three groups.

The events to be considered were predefined and chosen as those likely to be of considerable emotional significance to an ordinary woman. Systematic enquiries were then made of every woman in the samples regarding the occurrence of any such event in her life during the year before interview. For each event reported a number of ratings were then made, by research workers not involved in the interview, on how the event would be likely to affect a woman placed in the circumstances described. A crucial proviso was that, whilst these ratings took into account all information regarding the informant’s circumstances, they were made without knowledge of how she had actually reacted. Because of the importance of the findings a fuller account of the procedure adopted is given at the end of the section.

In their analysis of findings the most important rating scale yielding positive results was that dealing with the degree of threat or unpleasantness, lasting more than a week, that an event would be likely to pose to a woman placed in the particular circumstances described. This scale, termed by Brown and Harris the long-term contextual threat scale, proved, in their opinion, to be ‘the measure of crucial importance for understanding the aetiology of depression’, since, once this scale had been taken into account, scales covering other dimensions of events were not found to add anything further. In giving their findings they refer to any event rated as likely to pose a moderate or severe long-term threat to a woman placed in the circumstances described as a severe event.

When the proportions of women experiencing at least one severe event during the relevant preceding period are compared for the three groups, large and significant differences are found. Among patients the proportion experiencing at least one severe event is 61 per cent, among onset cases 68 per cent, and among the comparison group 20 per cent. Furthermore, among both the patient and the onset groups a much larger proportion than of the comparison group had experienced at least two severe events during the period: here the percentages are 27, 36 and 9 respectively.

As described more fully in Chapter 17, among the patients almost as high a proportion of women diagnosed as suffering a psychotic, or so-called endogenous, depression had experienced a severe event as of women diagnosed as suffering a neurotic, or so-called reactive, depression: figures are 58 per cent and 65 per cent respectively.

After examining the interval between the occurrences of a severe event and the onset of a depressive disorder, Brown and Harris conclude that in susceptible personalities ‘severe events usually lead fairly quickly to depression’. In two-thirds the period was nine weeks or less and, in almost all, onset was within six months.

Since one in five of the 382 women in the comparison group had experienced a severe event during the preceding 38 weeks without developing a depressive disorder, it remains a possibility that a severe event could have occurred by chance in the life of a patient-to-be during the period in question and have played no part in causing her depression. To allow for this contingency, Brown and Harris apply a statistical correction and conclude that in not less than 49 per cent of patients the severe event was of true causal importance, not merely the result of chance. This means that, had the patient-to-be not suffered the severe event, she would not have developed a depressive disorder at least for a long time and, more probably, not at all. This is a most important conclusion.

To this point we have said nothing about the nature of the events that were judged by the raters to constitute a severe event within the definition used. When this is examined it is found that a majority entailed loss or expected loss. In the words of Brown and Harris, ‘loss and disappointment are the central features of most events bringing about clinical depression’. In fact of all the events judged, in the circumstances in which they occurred, to pose a severe or moderately severe threat, whether occurring to depressed women or women in the comparison group, almost exactly half entailed the loss or expected loss of a person with whom the woman had a close relationship, namely her husband, her boyfriend or close confidant, or her child. The causes of such loss or expected loss were death, a life-threatening illness, a child leaving for distant places, and marital breakdown, manifested in desertion, a plan or threat to separate, or the unexpected discovery of a secret liaison.

A further 20 per cent of all the severe events recorded entailed a loss or expected loss of some other kind. In a few cases the event brought home to the woman the reality or irreversibility of a distressing situation in which she already was. Examples are an estranged pair who finally decide to make their separation legal, and the birth of a child to a woman whose marriage she knew had no future. Other events entailed the loss of something other than a personal relationship. These included loss of job and enforced removal from home.5

When all such losses are taken into account it is found that almost exactly half of the women suffering from depression had experienced a loss (48 per cent of patients and 59 per cent of onset cases) in contrast to 14 per cent of those in the comparison group. For the proportions for whom the loss in question had been a death the same ratio between groups holds: among patients 11 per cent, among onset cases 14 per cent, among the comparison group 4 per cent.

Although it would not be permissible on the basis of these findings to claim any simple equation between depressive disorders of all kinds and states of chronic mourning, the findings make plain, nevertheless, that there is a high degree of overlap between them. Moreover, the overlap is almost certainly greater than the figures given imply. For an examination of those women who were depressed but whose recent life experiences were not classified as having included a loss, or even a severe event, shows that a number of them had clearly been misclassified. For example, for one woman patient relevant material discovered later had not been available to the raters: her husband had been staying out late on a flimsy pretext and she had then discovered lipstick on his handkerchief, a discovery she had not divulged to the research interviewer. For another, an event had not been classified as severe because the object lost, a pet dog, had not been listed in the original definitions. This woman, a widow living with her mother, had had the dog for ten years and, two weeks before the onset of depression, had been forced to have it put down by her landlord. The emotional significance of the dog to her was evident: ‘he was our baby—our whole life was devoted to him’.

The work of Brown and Harris is being described at some length not only because their findings are of great importance for an understanding of depressive disorders but also because their work illustrates what care must be taken if the data necessary for the task in hand are to be obtained.

There are a number of reasons why the occurrence of an event of great emotional significance to the person concerned may be missed by a clinician or a research worker and, as a consequence, the disorder ensuing be dubbed mistakenly as endogenous. One lies in the personal nature of the events themselves and in the difficulties that some of them pose for an enquirer. The lipstick on the husband’s handkerchief, taken in context of the husband’s other behaviour, is one example. Others are anniversaries6 and analogous events that suddenly bring home to the person concerned the full impact of a past event.

A second reason, or set of reasons, why events of great significance may go unrecorded lies in the propensity of a person suffering from a depressive disorder either to be unwilling to confide the relevant information to the enquirer or else to be unable to do so either because of family pressure or because of being truly ignorant of what it is that is making him depressed. Unwillingness to tell a professional worker about an event that is extremely painful, and perhaps humiliating, is relatively easy to understand. That a person should be exposed to strong family pressure not to divulge the occurrence of certain events tends, however, to be neglected. Yet there is little doubt it plays a considerable role. Goodwin,7 for example, refers to it as having been a main problem in the study by Bunney, especially in retarded and psychotic patients. In illustration he describes a woman who had had a stillbirth four months before admission but who was unable to mention it until she had been in treatment many months. Within her family all reference to it was taboo. Even more difficult to remember, perhaps, is that a person may be truly ignorant of what it is that is troubling him. Yet, as already described, such ignorance certainly occurs.

The conclusion, noted earlier, that there is very considerable overlap between depressive disorders and states of chronic mourning is strengthened by a further finding of the Brown and Harris project. Women who develop a depressive disorder in adult life are more likely than others to have suffered the loss of mother during their childhood.

For purposes of this part of the enquiry the following three groups were studied: the 114 in the patient group, the 76 in the combined groups of community cases (chronic as well as onset), and the 382 in the comparison group.

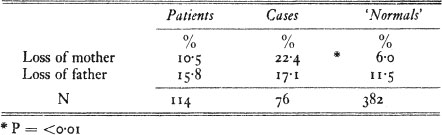

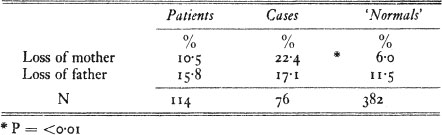

The incidence of loss of mother, due to death, desertion or a separation lasting twelve months or more,8 before the eleventh birthday for each of the three groups is shown in Table 4, together with the figures for loss of father. In both the patient group and the group of community cases, the incidence of loss of mother is higher than it is in the comparison group, and the same is true though to a lesser extent for loss of father. Of these differences the only one to reach statistical significance is loss of mother in the group of community cases as compared to the comparison group, 22·4 per cent and 6.0 per cent respectively.

TABLE 4 Incidence of loss of mother and of father, from all causes, before 11th birthday

The association between mother loss during childhood and depressive disorder among women in the community sample can be put another way. Among the whole sample of 458 women seen initially in the community there were 40 who had lost mother before their eleventh birthday and 418 who had not. Among the 40 who had lost mother no less than 17, or 42·5 per cent, had developed a depressive disorder; whereas among the 418 who had lived with mother in the usual way only 59, or 14·1 per cent, had done so. Thus among the whole community sample the incidence of depressive disorder was three times higher in the mother-loss sub-sample than it was in the mother-present sub-sample.

A question that arises from these findings is why the incidence of loss of or prolonged separation from mother before the eleventh birthday in the group of depressed women who were not in psychiatric care, i.e. the group of community cases, should be so much higher (22·4 per cent) than it is in those who were in psychiatric care, i.e. the group of patients (10·5 per cent). One possibility which the data gathered by Brown and Harris suggest is that the family circumstances of women who have lost or been separated from mother during their childhood are different to those of other women and that these very circumstances, for example, early marriage and several young children to care for without help, are such as to militate against their seeking medical or psychiatric treatment.

Whatever the explanation of this finding may turn out to be it is clear that future studies must no longer assume that a sample of individuals suffering from a disorder which is drawn from a psychiatric clinic is representative of all individuals suffering from that disorder.

The conclusions reached by Brown and Harris can now be summarized. The experience of loss can contribute causally to depressive disorders in any of three ways:

(a) as a provoking agent which increases risk of disorder developing and determines the time at which it does so: a majority of women in both the patient group and the onset case group had suffered a major loss from death or for other reason during the nine months prior to onset;

(b) as a vulnerability factor which increases an individual’s sensitivity to such events: in Brown’s study, and also in other studies see (Chapter 17), loss of mother before the age of eleven is of significance;

(c) as a factor that influences both the severity and the form of any depressive disorder that may develop: the findings of Brown and Harris relevant to these effects are given in Chapter 17.

Loss and related types of severe event, however, were not the only forms of personal experience found by Brown and Harris to be contributing causally to depressive disorders. Like losses, these other causal agents could be divided into those that act as determinants of onset and those that increase vulnerability. Among the former were certain sorts of family event that, although lying outside their definition of a severe event, were none the less very worrying or distressing and which had persisted for two years or more. Among the factors that seemed to have increased a woman’s vulnerability were the absence in her life of any intimate personal relationship, the presence of three or more children under fourteen to be cared for, and not going out to work.

It should be noted that the findings of Brown and Harris have not gone without criticism. For example, Tennant and Bebbington (1978) question both their procedure for diagnosing the cases of depressive disorder among the community sample and some of the statistical methods they used for analysing their data. This leads them to cast doubt on the distinction drawn between provoking agents and vulnerability factors. To these criticisms, however, Brown and Harris (1978b) have replied in convincing detail.

In order to deal with the methodological problems of how to identify events of emotional significance to an individual in a way that enables valid comparisons between groups to be made, a three-step procedure was adopted.

The first step was to identify events of possible importance that had occurred during the period in question. To this end 38 life events likely to evoke an emotional reaction in most people were defined in advance and in detail, and those persons in the respondent’s life who were to be covered specified. The interviewers had then to explore with each respondent whether or not one of these events had occurred during the relevant period and to record the facts as reported without asking any questions as to how the respondent may actually have reacted.

The period chosen for this enquiry was the year before interview. For women in both the patient and the onset case groups this covered a period averaging 38 weeks before the onset of symptoms.

Although this first step provided a reliable method of identifying the occurrence of certain sorts of event, it failed (deliberately) to take account of an individual’s personal circumstances and the meaning that the event would be likely to have for someone in those particular circumstances. This was made good by the second and third steps.

Having identified the occurrence of an event conforming to the criteria used, the interviewers next covered, in as informal a way as possible, a lengthy list of questions about what had led up to and what had followed each event, and the feelings and attitudes surrounding it. In addition to questions, the interviewer encouraged each woman to talk at length and, by suitable enquiries, also sought to obtain extensive biographical material. All interviews were taperecorded.

Since the recording of life events and their meaning was to be done for every member of the three samples on a strictly comparable basis, it was necessary next to assess the meaning that each event reported would be likely to have for a woman placed in the particular circumstances described and to do so according to some yardstick that could be applied generally and without reference to the particular way that the woman being questioned happened to have reacted. This was the third step.

For each event reported a large number of ratings were made, by research workers not involved in the interview. One rating concerned the ‘independence’ of the event, that is the degree to which it could be viewed as independent of the respondent’s own conscious behaviour. The other scales considered how the event would be likely to affect a woman placed in the circumstances described. These ratings, made on a four-point scale, took into account all information regarding the informant’s circumstances but without knowledge of how she had actually reacted. Initially, each rater, working independently, made a rating on each of the scales. Thereafter the raters discussed any discrepancies and agreed a final rating. Interrater agreement was high. Raters were helped in their task not only by their regular discussions but also by a series of anchoring examples illustrating the four points on each scale, and by certain fairly standard conventions.

By following this rather lengthy procedure the researchers aimed to close the yawning scientific gap left by the two research methods traditionally employed, namely the clinical case history with its enormously rich detail but which lacks either comparison groups or safeguards against circular reasoning, and the epidemiological approach which, though strong in safeguards, has hitherto been bare of personal meanings.

It is important to realize that to attribute a major role in the aetiology of depressive disorders to psychosocial events, and in particular to separation and loss, does not preclude attributing a significant role also to neurophysiological processes.

That there is a relationship between abnormal levels of certain neuroendocrines and neurotransmitters, on the one hand, and affective states and disorders, on the other, is now fairly certain. Controversy begins when questions are raised about their causal relatedness. One school of thought has made the simple assumption that the causal sequence is always in one direction, from the changes in neurophysiological processes to the changes in affect and cognition. Yet it is now clear that the causal sequence can equally well run in the opposite direction. Research shows that cognitive and affective states of anxiety and depression, induced in adults by events such as separation and loss, may not only be accompanied by significant changes in the levels of certain neuroendocrines but that these changes are similar to those known often to be present in adults suffering from depression. That comparable changes can occur also in children who are subjected to separation and loss seems probable.9 Once brought about, these neuroendocrinological changes may then prolong or intensify the depressive reaction. Readers interested in this field are referred to a comprehensive review by Hamburg, Hamburg and Barchas (1975).

Not unexpectedly, studies show that the size and pattern of neurophysiological responses to psychological events differ greatly from person to person. Such differences are probably responsible, in part at least, for differences between individuals in their degree of vulnerability to these events. Some of the differences are likely to be of genetic origin. Yet that is not the only possibility. An alternative source of difference could be differences in childhood experience. Thus, it is conceivable that the state of the neuroendocrine system of individuals who are subjected to severely stressing conditions during childhood might be permanently changed so that it becomes thereafter either more sensitive or less so. In any case genetic influences never operate in a vacuum. During development complex interactions between genetic and environmental influences are the rule; and it is especially when organisms are under stress that genetic differences between them are likely to be of most consequence.

1 From Draft G, circa January 1895 (S. Freud 1954).

2 To reflect my belief that there are true differences of kind between clinical depression and a normal depressive mood, in what follows I refer to the clinical conditions, variously termed ‘clinical depressions’, ‘clinical depressive states’ or ‘depressive illnesses’ as ‘depressive disorders’. My reasons for adopting this terminology are, first, that I believe the clinical conditions are best understood as disordered versions of what is otherwise a healthy response and, secondly, that, whilst the term disorder is compatible with medical thinking, it is not tied specifically to the medical model as are the terms ‘clinical’ and ‘illness’.

3 A common motive for a parent, usually a mother, to speak to a child or adolescent in this kind of way is to ensure that he remains at home to care for her (as described in the section ‘Experiences disposing towards compulsive caregiving’ in Chapter 12). Most misleadingly, pressure of this kind is often mistaken for ‘overprotection’.

When this mislabelling is allowed for, the conclusions reached by Parker (1979) are seen to be consistent with the types of childhood experience postulated above. As a result of a questionnaire study of 50 depressed women patients and 50 controls he concludes that the depressed patients are significantly more likely than the controls to regard their mothers as having treated them with a combination of ‘low care’ and ‘high overprotection’. The figures are 60 per cent and 24 per cent respectively.

4 Since for purposes of the research it was essential that the date of onset was recorded accurately, the investigators used a special interviewing procedure which was used also for the patient group. A test of its validity, in which the date of onset given by a patient was compared with the one given independently by a relative, proved satisfactory.

5 In a comparable study by Paykel (1974) two-thirds of the events found to precede the onset of depressive illness were classified as ‘exits’ which are roughly the equivalent of what Brown and Harris classify as losses or expected losses.

In another study, by a group led by William Bunney (Leff, Roatch and Bunney 1970), however, the events occurring most frequently before onset are described as ‘threats to sexual identity’, followed in order of frequency by ‘changes in the marital relationship’. Except for seven patients who had experienced the death of someone close (17 per cent), the category of loss was not used. Yet inspection of their data shows that in a number of cases, for example of divorce, separation or jilting by boyfriend, the event in question could equally well, or better, have been categorized as a loss.

6 Anniversaries were not on the list of predefined events used by Brown and Harris. The reasons for their omission were the methodological difficulties of obtaining information about them systematically, not that they were thought to be of no importance (personal communication).

7 Reported in Friedman and Katz (1974, p. 151).

8 Periods of wartime evacuation were not taken into account because information was not collected on all subjects. For particulars see Brown et al. (1977).

9 Such changes certainly occur in infant monkeys. For example, McKinney (1977), in a review of studies of animal models of depressive disorders, reports that, in four-month-old rhesus macaques that had been separated from mother for six days, major alterations were found in both the peripheral and the central brain amine systems of the animals.