Eva was experiencing grief for the first time. When Keir had first broken the news to her of John’s illness she had experienced shock, but that had been different—almost the opposite. For that had been an inability to feel, whereas this was an inability not to feel—an ugly, uncontrollable glut of emotion that distended her until she felt she might burst and be a splatter of guts on the floor . . . She wanted to smash something, howl. She wanted to throw herself on the floor, roll about, kick, scream.

BRYAN MAGEE, Facing Death

THERE IS NOW a good deal of reliable information about how adults respond to a major bereavement. In addition to data reported by early students of the subject, already referred to in previous chapters and in Appendices I and II of Volume II, observations are now available deriving from later and more carefully designed projects. Those most useful for our present purposes are studies in which observations are begun shortly after a bereavement, and in some cases before it has occurred, and are then continued for a year or more afterwards. In this chapter and those following we draw extensively on the findings of such projects. They fall into two main classes. The first, described in this chapter, comprises studies which aim to describe typical patterns of response to the loss of a spouse during the first year of bereavement and, further, to identify features which may predict whether the state of health, physical and mental, of the mourner at the end of the first year will be favourable or unfavourable. The second group comprises studies of the course of mourning in the parents of fatally-ill children and are described in the chapter following.

It is evident that to be ethical all such studies must be conducted with sensitivity and sympathy and only with those who are willing to participate. Experience shows that, when so conducted, a majority of the subjects co-operate actively and, moreover, are usually grateful for the opportunity to express their sorrow to an understanding person.

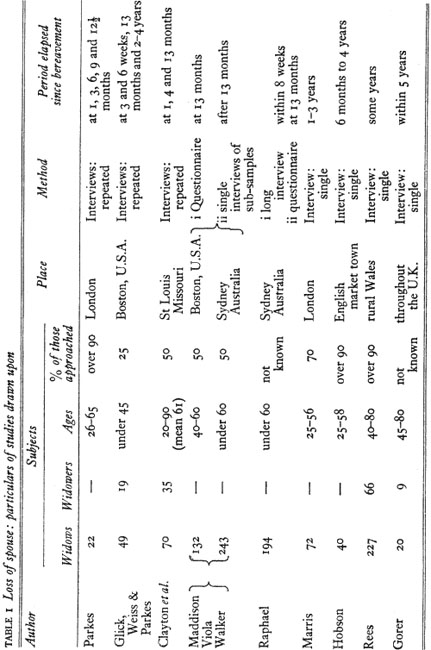

Table 1 lists the principal studies drawn on in this chapter and in Chapters 9 to 12 giving certain basic information about each. Each sought to be as representative of the population studied as was possible: thus members of all socio-economic classes were approached. In the degree to which they were successful in tracing and in obtaining the co-operation of those approached, however, studies varied greatly-from over 90 per cent success in some to no more than 25 per cent in others.

In almost every study interviews were held in the bereaved’s home, by prior arrangement, and lasted at least an hour, sometimes as long as three hours. In most studies interviews were semi-structured, aimed both to give the bereaved an opportunity to talk freely about his or her experiences and also to ensure that certain fields were covered adequately.

The studies to which I am especially indebted are those by my colleague Colin Murray Parkes, one of which he conducted in London (Parkes 1970a) and the other, in association with Ira O. Glick and Robert S. Weiss, in Boston, Mass. (Glick, Weiss and Parkes 1974, second volume in preparation).

Readers wishing to have further information regarding the samples of subjects studied, the procedures employed, and the publications in which results are given are referred to the note at the end of this chapter.

Taken together we find that the number of widows and widowers included in these samples total several hundred; and we find also that with few exceptions the degree of agreement between the findings is impressive. Yet we must ask ourselves how representative of all bereaved spouses the samples studied are.

First it will be noted that in the studies described there are many more widows than widowers. This is not surprising since, because of their higher relative age and lower life expectancy, husbands die relatively far more frequently than wives. Thus, we find ourselves better informed of the course of mourning in women than in men, so that there is danger that generalizations may reflect this imbalance. In what follows, therefore, we describe first the course taken by mourning in widows and at the end of the chapter discuss what is known regarding differences in the course taken by mourning in widowers. In general the pattern of emotional response to loss of a spouse appears to be similar in the two sexes. Such differences as there are can be regarded as variations in the ways that men and women, of Western cultures, deal with their emotional responses and with the ensuing disruption of their way of life.

Secondly, most of the samples are biased towards the younger age groups. The Harvard study excludes all subjects over the age of forty-five; Marris excludes almost all those over fifty; Hobson, and also Maddison and his colleagues, those over sixty. Only in the case of the studies by Clayton and her colleagues, by Rees and by Gorer are there included any widows or widowers over the age of sixty-five. This bias has been deliberate because many of the workers engaged have been concerned to study subjects whom it was thought were at relatively high risk of suffering serious or prolonged emotional disturbance, and such evidence as there was suggested that intensity of reaction, and perhaps also difficulty in recovering, tend to be greater in younger subjects than in older ones. The reason for this, recent evidence suggests, is that the age at which a person suffers loss of a spouse or of a child is correlated with the degree to which the death is felt to have been untimely, to have cut short a life before its fulfilment. For it is evident that the younger the widow or widower, the younger is the husband or wife who has died likely to have been, and the more likely therefore is the death to be felt by the bereaved as having been untimely.

Next, we have to consider how findings may be affected by most of the samples having comprised volunteers drawn from larger populations of bereaved people. To what extent are the responses of these volunteers typical of those that would be seen in the larger population? There is no easy way to answer this, but such evidence as is available, especially that from the comprehensive studies of Hobson (1964) and Rees (1971), does not suggest that responses of volunteers are biased in any systematic way. The same conclusion is reached by Marris (1958) in regard to his London sample and also by Glick et al (1974) in regard to their Boston sample. In both cases those who participated differed little from the non-participators in regard to demographic variables. In addition, in the Boston study a telephone call to a sample of the non-participators about two years after the first (abortive) contact suggested that their emotional and other experiences after bereavement had not been dissimilar to the experiences of those who had participated in the study.

Finally, it must be recognized that the subjects of these studies come exclusively from the Western world. Would similar findings obtain elsewhere? Though evidence to answer this question is inadequate, such as there is suggests that overall patterns are indeed similar. A few examples of this evidence are presented in Chapter 8.

Observations of how individuals respond to the loss of a close relative show that over the course of weeks and months their responses usually move through a succession of phases. Admittedly these phases are not clear cut, and any one individual may oscillate for a time back and forth between any two of them. Yet an overall sequence can be discerned.

The four1 phases are as follows:

In what follows we concentrate especially on the psychological responses to loss, with special reference to the way the original relationship continues to fill a central role in a bereaved person’s emotional life yet also, as a rule, undergoes a slow change of form as the months and years pass.2 This continuing relationship explains the yearning and searching, and also the anger, prevalent in the second phase, and the despair and subsequent acceptance of loss as irreversible that occur when phases three and four are passed through successfully. It explains, too, many, and perhaps all, of the features characteristic of pathological outcomes.

In the descriptions of responses typical of the first two phases we draw especially on Parkes’s study of London widows. In descriptions of the second two phases we draw increasingly on the findings of the Harvard and other studies.

The immediate reaction to news of a husband’s death varies greatly from individual to individual and also from time to time in any one widow. Most feel stunned and in varying degrees unable to accept the news. Remarks such as ‘I just couldn’t take it all in’, ‘I couldn’t believe it’, ‘I was in a dream’, ‘It didn’t seem real’ are the rule. For a time a widow may carry on her usual life almost automatically. Nevertheless, she is likely to feel tense and apprehensive; and this unwonted calm may at any moment be broken by an outburst of intense emotion. Some describe overwhelming attacks of panic in which they may seek refuge with friends. Others break into anger. Occasionally a widow may feel sudden elation in an experience of union with her dead husband.

Within a few hours or, perhaps, a few days of her loss a change occurs and she begins, though only episodically, to register the reality of the loss: this leads to pangs of intense pining and to spasms of distress and tearful sobbing. Yet, almost at the same time, there is great restlessness, insomnia, preoccupation with thoughts of the lost husband combined often with a sense of his actual presence, and a marked tendency to interpret signals or sounds as indicating that he is now returned. For example, hearing a door latch lifted at five o’clock is interpreted as husband returning from work, or a man in the street is misperceived as the missing husband. Vivid dreams of the husband still alive and well are not uncommon, with corresponding desolation on waking.

Since some or all of these features are now known to occur in a majority of widows, there can no longer be doubt that they are a regular feature of grief and in no way abnormal.

Another common feature of the second phase of mourning is anger. Its frequency as part of normal mourning has, we believe, habitually been underestimated, at least by clinicians, to whom it seems to have appeared out of place and irrational. Yet, as remarked in Chapter 2, it has been reported by every behavioural scientist, of whatever discipline, who has made grieving the centre of his research.

When such evidence as was then available was examined some years ago (Bowlby 1960b, 1961b) I was struck by the resemblance of these responses to a child’s initial protest at losing his mother and his efforts to recover her and also by Shand’s suggestion that searching for the lost person is an integral part of the mourning of adults. The view I advanced, therefore, was that during this early phase of mourning it is usual for a bereaved person to alternate between two states of mind. On the one hand is belief that death has occurred with the pain and hopeless yearning that that entails. On the other is disbelief3 that it has occurred, accompanied both by hope that all may yet be well and by an urge to search for and to recover the lost person. Anger is aroused, it seems, both by those held responsible for the loss and also by frustrations met with during fruitless search.

Exploring this view further, I suggested that in bereaved people whose mourning runs a healthy course the urge to search and to recover, often intense in the early weeks and months, diminishes gradually over time, and that how it is experienced varies greatly from person to person. Whereas some bereaved people are conscious of their urge to search, others are not. Whereas some willingly fall in with it, others seek to stifle it as irrational and absurd. Whatever attitude a bereaved person takes towards the urge, I suggested, he none the less finds himself impelled to search and, if possible, to recover the person who has gone. In a subsequent paper (Bowlby 1963) I pointed out that many of the features characteristic of pathological forms of mourning can be understood as resulting from the active persistence of this urge which tends to be expressed in a variety of disguised and distorted ways.

Such were the views advanced in the early sixties. They have since been endorsed and elaborated by Parkes, who has given special attention to these issues. In one of his papers (Parkes 1970b) he has set out evidence from his own studies which he believes supports the search hypothesis. Since this hypothesis is central to all that follows, his evidence is given below.

Introducing the thesis he writes: ‘Although we tend to think of searching in terms of the motor act of restless movement towards possible locations of the lost object, [searching] also has perceptual and ideational components . . . Signs of the object can be identified only by reference to memories of the object as it was. Searching the external world for signs of the object therefore includes the establishment of an internal perceptual “set” derived from previous experiences of the object.’ He gives as example a woman searching for her small son who is missing; she moves restlessly about the likely parts of the house scanning with her eyes and thinking of the boy; she hears a creak and immediately identifies it as the sound of her son’s footfall on the stair; she calls out, ‘John, is that you?’ The components of this sequence are:

‘Each of these components,’ Parkes emphasizes, ‘is to be found in bereaved men and women: in addition some grievers are consciously aware of an urge to search.’

Presenting his findings on the 22 London widows under these five heads Parkes reports that:

(a) All but two widows said they felt restless during the first month of bereavement, a restlessness that was also evident during interview. In summarizing his own findings Parkes quotes Lindemann’s classical description of the early weeks of bereavement: ‘There is no retardation of action and speech; quite to the contrary, there is a rush of speech especially when talking about the deceased. There is restlessness, inability to sit still, moving about in aimless fashion, continually searching for something to do’ (Lindemann 1944). Nevertheless, Parkes believes the searching is by no means aimless. Only because it is inhibited or else expressed in fragmentary fashion does it appear so.

(b) During the first month of bereavement 19 of the widows were preoccupied with thoughts of their dead husband, and a year later 12 continued to spend much time thinking of him. So clear was the visual picture that often it was spoken of as if it were a perception: ‘I can see him sitting in the chair.’

(c) The likelihood that this clear visual picture is part of a general perceptual set that scans sensory input for evidence of the missing person is supported by the frequency with which widows misidentify sensory data. Nine of those interviewed described how during the first month of bereavement they had frequently construed sounds or sights as indicative of their husband. One supposed she heard him cough at night, another heard him moving about the house, a third repeatedly misidentified men in the street.

(d) Not only is a widow’s perceptual set biased to give precedence to sensory data that may give evidence of her husband, but her motor behaviour is biased in a comparable way. Half the widows Parkes interviewed described how they felt drawn towards places or objects which they associated with him. Six kept visiting old haunts they had frequented together, two felt drawn towards the hospital where their husband had died, in one case to the point of actually entering its doors, three were unable to leave home without experiencing a strong impulse to return there, others felt drawn towards the cemetery where he was buried. All but three treasured possessions associated with their husband and several found themselves returning repeatedly to such objects.

(e) Whenever a widow recalls the lost person or speaks about him tears are likely, and sometimes they lead to uncontrollable sobbing. Although it may come as a surprise that such tears and sobs are to be regarded as attempts to recover the lost person, there is good reason to think that that is what they are.

The facial expressions typical of adult grief, Darwin concluded (1872), are a resultant, on the one hand, of a tendency to scream like a child when he feels abandoned and, on the other, of an inhibition of such screaming. Both crying and screaming are, of course, ways by means of which a child commonly attracts and recovers his missing mother, or some other person who may help him find her; and they occur in grief, we postulate, with the same objective in mind—either consciously or unconsciously. In keeping with this view is the finding that occasionally a bereaved person will call out for the lost person to return. ‘Oh, Fred, I do need you,’ shouted one widow during the course of an interview before she burst into tears.

Finally, at least four of these 22 widows were aware that they were searching. ‘I walk around searching,’ said one, ‘I go to the grave . . . but he’s not there,’ said another. One of them had ideas of attending a spiritualist seance in the hope of communicating with her husband; several thought of killing themselves as a means of rejoining theirs.4

Turning now to the incidence of anger amongst these widows, Parkes found it to be evident in all but four and to be very marked in seven, namely one-third of them, at the time of the first interview. For some, anger took the form of general irritability or bitterness. For others it had a target—in four cases a relative, in five clergy, doctors or officials, and in four the dead husband himself. In most such cases the reason given for the anger was that the person in question was held either to have been in some part responsible for the death or to have been negligent in connection with it, either towards the dead man or to the widow. Similarly, husbands had incurred their widows’ anger either because they had not cared for themselves better or because they were thought to have contributed to their own death.5

Although some degree of self-reproach was also common, it was never so prominent a feature as was anger. In most of these widows self-reproach centred on some minor act of omission or commission associated with the last illness or death. Although in one or two of the London widows there were times when this self-reproach was fairly severe, in none of them was it as intense and unrelenting as it is in subjects whose self-reproachful grieving persists until finally it becomes diagnosed as depressive illness see (Chapter 9).

Within the context of the search hypothesis the prevalence of anger during the early weeks of mourning receives ready explanation. In several earlier publications (see Volume II, Chapter 17) it has been emphasized that anger is both usual and useful when separation is only temporary. It then helps overcome obstacles to reunion with the lost person; and, after reunion is achieved, to express reproach towards whomever seemed responsible for the separation makes it less likely that a separation will occur again. Only when separation is permanent is the anger and reproach out of place. ‘There are therefore good biological reasons for every separation to be responded to in an automatic instinctive way with aggressive behaviour; irretrievable loss is statistically so unusual that it is not taken into account. In the course of our evolution, it appears, our instinctual equipment has come to be so fashioned that all losses are assumed to be retrievable and are responded to accordingly’ (Bowlby 1961b). Thus anger is seen as an intelligible constituent of the urgent though fruitless effort a bereaved person is making to restore the bond that has been severed. So long as anger continues, it seems, loss is not being accepted as permanent and hope is still lingering on. As Marris (1958) comments when a widow described to him how, after her husband’s death, she had given her doctor a good hiding, it was ‘as if her rage while it lasted had given her courage’.

Sudden outbursts of rage are fairly common soon after a loss, especially ones that are sudden and/or felt to be untimely, and they carry no adverse prognosis. Should anger and resentment persist beyond the early weeks, however, there are grounds for concern, as we see in Chapter 9.

Hostility to comforters is to be understood in the same way. Whereas the comforter who takes no side in the conflict between a striving for reunion and an acceptance of loss may be of great value to the bereaved, one who at an early stage seems to favour acceptance of loss is as keenly resented as if he had been the agent of it. Often it is not comfort in loss that is wanted but assistance towards reunion.

Anger and ingratitude towards comforters, indeed, have been notorious since the time of Job. Overwhelmed by the blow he has received, one of the first impulses of the bereaved is to appeal to others for their help—help to regain the person lost. The would-be comforter who responds to this appeal may, however, see the situation differently. To him it may be clear that hope of reunion is a chimera and that to encourage it would be unrealistic, even dishonest. And so, instead of behaving as is wished, he seems to the bereaved to do the opposite and is resented accordingly. No wonder his role is a thankless one.

Thus, we see, restless searching, intermittent hope, repeated disappointment, weeping, anger, accusation, and ingratitude are all features of the second phase of mourning, and are to be understood as expressions of the strong urge to find and recover the lost person. Nevertheless, underlying these strong emotions, which erupt episodically and seem so perplexing, there is likely to coexist deep and pervasive sadness, a response to recognition that reunion is at best improbable. Moreover, because fruitless search is painful, there may also be times when a bereaved person may attempt to be rid of reminders of the dead. He or she may then oscillate between treasuring such reminders and throwing them out, between welcoming the opportunity to speak of the dead and dreading such occasions, between seeking out places where they have been together and avoiding them. One of the widows interviewed by Parkes described how she had tried sleeping in the back bedroom to get away from her memories and how she had then missed her husband so much that she had returned to the main bedroom in order to be near him.

Finding a way to reconcile these two incompatible urges, we believe, constitutes a central task of the third and fourth phases of mourning. Light on how successfully the task is being solved, Gorer (1965) believes, is thrown by the way a bereaved person responds to spoken condolences; grateful acceptance is one of the most reliable signs that the bereaved is working through his or her mourning satisfactorily. Conversely, as we see in Chapter 9, an injunction never to refer to the loss bodes ill.

It is in the extent to which they help a mourner in this task that mourning customs are to be evaluated. In recent times both Gorer (1965) and Marris (1974) have considered them in this light. At first, Marris points out, acts of mourning attenuate the leave taking. They enable the bereaved, for a while, to give the dead person as central a place in her life as he had before, yet at the same time they emphasize death as a crucial event whose implications must be acknowledged. Subsequently, such customs mark the stages of reintegration. In Gorer’s phrase, mourning customs are ‘time-limited’, both guiding and sanctioning the stages of recovery. Although at first sight it may seem false to impose customs on so intense and private an emotion as grief, the very loneliness of the crisis and the intense conflict of feeling cries out for a supportive structure. In Chapter 8 the mourning customs of other cultures are considered and attention drawn to certain features that are common to a large majority of them, including those of the West.

For mourning to have a favourable outcome it appears to be necessary for a bereaved person to endure this buffeting of emotion. Only if he can tolerate the pining, the more or less conscious searching, the seemingly endless examination of how and why the loss occurred, and anger at anyone who might have been responsible, not sparing even the dead person, can he come gradually to recognize and accept that the loss is in truth permanent and that his life must be shaped anew. In this way only does it seem possible for him fully to register that his old patterns of behaviour have become redundant and have therefore to be dismantled. C. S. Lewis (1961) has described the frustrations not only of feeling but of thought and action that grieving entails. In a diary entry after the loss of his wife, H, he writes: ‘I think I am beginning to understand why grief feels like suspense. It comes from the frustration of so many impulses that had become habitual. Thought after thought, feeling after feeling, action after action, had H for their object. Now their target is gone. I keep on, through habit, fitting an arrow to the string; then I remember and I have to lay the bow down. So many roads lead through to H. I set out on one of them. But now there’s an impassable frontier-post across it. So many roads once; now so many culs-de-sac’ (p. 59).

Because it is necessary to discard old patterns of thinking, feeling and acting before new ones can be fashioned, it is almost inevitable that a bereaved person should at times despair that anything can be salvaged and, as a result, fall into depression and apathy. Nevertheless, if all goes well this phase may soon begin to alternate with a phase during which he starts to examine the new situation in which he finds himself and to consider ways of meeting it. This entails a redefinition of himself as well as of his situation. No longer is he a husband but a widower. No longer is he one of a pair with complementary roles but a singleton. This redefinition of self and situation is as painful as it is crucial, if only because it means relinquishing finally all hope that the lost person can be recovered and the old situation re-established. Yet until redefinition is achieved no plans for the future can be made.

It is important here to note that, suffused though it be by the strongest emotion, redefinition of self and situation is no mere release of affect but a cognitive act on which all else turns. It is a process of ‘realization’ (Parkes 1972), of reshaping internal representational models so as to align them with the changes that have occurred in the bereaved’s life situation. Much is said of this in later chapters.

Once this corner is turned a bereaved person recognizes that an attempt must be made to fill unaccustomed roles and to acquire new skills. A widower may have to become cook and housekeeper, a widow to become the family wage-earner and house decorator. If there are children, the remaining parent has so far as possible to do duty for both. The more successful the survivor is in achieving these new roles and skills the more confident and independent he or she begins to feel. The shift is well described by one of the London widows, interviewed a year after her bereavement, who remarked: ‘I think I’m beginning to wake up now. I’m starting living instead of just existing . . . I feel I ought to plan to do something.’ As initiative and, with it, independence returns so a widow or widower may become jealous of that independence and may perhaps break off rather abruptly a supportive relationship that had earlier been welcomed. Yet, however successfully a widow or widower may adopt new roles and learn new skills, the changed situation is likely to be felt as a constant strain and is bound to be lonely. An acute sense of loneliness, most pronounced at night time, was reported by almost all the widows interviewed whether by Marris, by Hobson or by Parkes in England or by Glick or Clayton and their respective teams in the U.S.A.

To resume social life even at a superficial level is often a great difficulty, at least in Western cultures. There is more than one reason for this. On the one hand, convention often dictates that the sexes be present in equal number so that those who enjoy the company of the other sex find themselves left out. On the other are those who find social occasions in which the sexes are mixed too painful to attend because of their being reminded too forcefully of their loss of partner. As a consequence we find that both widowers and widows most often join gatherings of members of their own sex. For men this is usually easier because a work group or sports group may be ready to hand. For women a church group or Women’s Institute may prove invaluable.

Few widows remarry. This is partly because suitable partners are scarce but at least equally because of a reluctance of many widows to consider remarriage. Plainly, the remarriage rate for each sample will depend not only on the widows’ ages at bereavement but on the number of years later that information is gathered. In the studies reviewed here the highest rate reported is about one in four of the Boston widows; at the end of some three years fourteen had either remarried or appeared likely to do so. All of them, it should be remembered, were under 45 years when widowed. In the Marris study one in five of the 33 widowed before age forty had remarried. For older widows the proportions are much lower. By contrast, the proportion of widowers who remarry is relatively high, a difference considered further at the end of the chapter.

Many widows refuse to consider remarriage. Others consider it but decide against it. Fear of friction between stepfather and children is given as a reason by many. Some regard the risk of suffering the pain of a second loss too great. Others believe they could never love another man in the way they had loved their husband and that invidious comparisons would result. In response to questions, about half the Boston widows expressed themselves uninterested in any further sexual relationship. Whilst half of the total acknowledged some sense of sexual deprivation, others felt numbed. It is probably common for sexual feelings to continue to be linked to the husband; and they may be expressed in masturbation fantasies or enacted in dreams.

A year after bereavement, continued loyalty to the husband was judged by Glick to be the main stumbling-block to remarriage in the case of the Boston widows. Parkes remarks that many of the London widows ‘still seemed to regard themselves as married to their dead husbands’ (Parkes, 1972, p. 99). This raises afresh the issue of a bereaved person’s continuing relationship with the person who has died.

As the first year of mourning draws on most mourners find it becomes possible to make a distinction between patterns of thought, feeling and behaviour that are clearly no longer appropriate and others which can with good reason be retained. In the former class are those, such as performing certain household duties, which only make sense if the lost person is physically present; in the latter maintaining values and pursuing goals which, having been developed in association with the lost person, remain linked with him and can without falsification continue to be maintained and pursued in reference to memory of him. Perhaps it is through processes of this kind that half or more of widows and widowers reach a state of mind in which they retain a strong sense of the continuing presence of their partner without the turmoils of hope and disappointment, search and frustration, anger and blame that are present earlier.

It will be remembered that a year after losing their husbands twelve of the twenty-two London widows reported that they still spent much time thinking of their husband and sometimes had a sense of his actual presence. This they found comforting. Glick et al. (1974) report very similar findings for the Boston widows. Although a sense of the continuing presence of the dead person may take a few weeks to become firmly established, they found it tends thereafter to persist at its original intensity, instead of waning slowly as most of the other components of the early phases of mourning do. Twelve months after their loss two out of three of the Boston widows continued to spend much time thinking of their husband and one in four of the 49 described how there were still occasions when they forgot he was dead. So comforting did widows find the sense of the dead husband’s presence that some deliberately evoked it whenever they felt unsure of themselves or depressed.

Similar findings to those for the London and the Boston widows are reported also by Rees (1971), who surveyed nearly three hundred widows and widowers in Wales, nearly half of whom had been widowed for ten years or longer. Of 227 widows and 66 widowers 47 per cent described having had such experiences and a majority were continuing to do so. Incidence in widowers was almost the same as in widows and the incidence varied little with either social class or cultural background. The incidence tended to be higher the longer the marriage had lasted, which may account for its being higher also in those who were over the age of forty when widowed. More than one in ten of widows and widowers reported having held conversations with the dead spouse; and here again the incidence was higher in older widows and widowers than in younger ones. Two-thirds of those who reported experiences of their dead spouse’s presence, either with or without some form of sensory illusion or occasionally hallucination, described their experiences as being comforting and helpful. Most of the remainder were neutral about them, and only eight of the total of 137 subjects who had such experiences disliked having them.

Dreams of the spouse still being alive share many of the characteristic features of the sense of presence: they occur in about half of widows and widowers, they are extremely vivid and realistic and in a majority of cases are experienced as comforting. ‘It was just like everyday life’, one of the London widows reported, ‘my husband coming in and getting his dinner. Very vivid so that when I woke up I was very annoyed.’ Several of Gorer’s informants described how they sought to hold the image in their minds after waking and how sad it was when it faded. Not infrequently a widow or widower would weep after recounting the dream.

Gorer (1965) emphasizes that in these typical comforting dreams the dead person is envisaged as young and healthy, and as engaging in happy everyday activities. But, as Parkes (1972) notes, as a rule there is something in the dream to indicate that all is not well. As one widow put it after describing how in the dream her husband was trying to comfort her and how happy it made her: ‘even in the dream I know he’s dead’.6

Not all bereaved people who dream find the dream comforting. In some dreams traumatic aspects of the last illness or death are re-enacted; in others distressing aspects of the previous relationship. Whether on balance a bereaved person finds his dreams comforting seems likely to be a reliable indicator of whether or not mourning is taking a favourable course.

Let us return now to a widow’s or widower’s daytime sense of the dead spouse’s presence. In many cases, it seems, the dead spouse is experienced as a companion who accompanies the bereaved everywhere. In many others the spouse is experienced as located somewhere specific and appropriate. Common examples are a particular chair or room which he occupied, or perhaps the garden, or the grave. As remarked already, there is no reason to regard any of these experiences as either unusual or unfavourable, rather the contrary. For example, in regard to the Boston widows Glick et al. (1974) report: ‘Often the widow’s progress toward recovery was facilitated by inner conversations with her husband’s presence . . . this continued sense of attachment was not incompatible with increasing capacity for independent action’ (p. 154). Although Glick regards this finding as paradoxical, those familiar with the evidence regarding the relation of secure attachment to the growth of self-reliance (Volume II, Chapter 21) will not find it so. On the contrary, it seems likely that for many widows and widowers it is precisely because they are willing for their feelings of attachment to the dead spouse to persist that their sense of identity is preserved and they become able to reorganize their lives along lines they find meaningful.

That for many bereaved people this is the preferred solution to their dilemma has for too long gone unrecognized.

Closely related to this sense of the dead person’s presence are certain experiences in which a widow may feel either that she has become more like her husband since his death or even that he is somehow within her. For example, one of the London widows, on being asked whether she had felt her husband was near at hand, replied: ‘It’s not a sense of his presence, he’s here inside me. That’s why I’m happy all the time. It’s as if two people are one . . . although I’m alone, we’re sort of together if you see what I mean . . . I don’t think I’ve got the will power to carry on on my own, so he must be’ (Parkes 1972, p. 104).

In accordance with such feelings bereaved people may find themselves doing things in the same way that the person lost did them; and some may undertake activities typical of the dead person despite their never having done them before. When the activities are well suited to the capabilities and interests of the bereaved, no conflict results and he or she may obtain much satisfaction from doing them. Perhaps such behaviour is best regarded as an example, in special circumstances, of the well-known tendency to emulate those whom we hold in high regard. Nevertheless, Parkes (1972, p. 105) emphasizes that in his series of London widows it was only a minority who at any time during the first year of bereavement were conscious either of coming to resemble the husband or of ‘containing’ him. Moreover, in these widows the sense of having him ‘inside’ tended to alternate with periods when he was experienced as a companion. Since these widows progressed neither more nor less favourably than others, such experiences when only short-lived are evidently compatible with healthy mourning.

Many symptoms of disordered mourning can, however, be understood as due to some unfavourable development of these processes. One form of maldevelopment is when a bereaved person feels a continuing compulsion to imitate the dead person despite having neither the competence nor the desire to do so. Another is when the bereaved’s continuing sense of ‘containing’ the person lost gives rise to an elated state of mind (as seems to have been present in the example quoted), or leads the bereaved to develop the symptoms of the deceased’s last illness. Yet another form of unfavourable development occurs when the bereaved, instead of experiencing the dead person as a companion and/or as located somewhere appropriate such as in the grave or in his, or her, familiar chair, locates him within another person, or even within an animal or a physical object. Such mislocations as I shall call them, which include mislocations within the self, can if persistent easily lead to behaviour that is not in the best interests of the bereaved and that may appear bizarre. It may also be damaging to another person; for example, to regard a child as the incarnation of a dead person and to treat him so is likely to have an extremely adverse effect upon him see (Chapter 16). For all these reasons I am inclined to regard mislocations of any of these kinds if more than transitory as signs of pathology.

Failure to recognize that a continuing sense of the dead person’s presence, either as a constant companion or in some specific and appropriate location, is a common feature of healthy mourning has led to much confused theorizing. Very frequently the concept of identification, instead of being limited to cases in which the dead person is located within the self, is extended to cover also every case in which there is a continuing sense of the dead person’s presence, irrespective of location. By so doing a distinction that recent empirical studies show is vital for an understanding of the differences between healthy and pathological mourning becomes blurred. Indeed, findings in regard both to the high prevalence of a continuing sense of the presence of the dead person and to its compatibility with a favourable outcome give no support to Freud’s well-known and already quoted passage: ‘Mourning has a quite precise psychical task to perform: its function is to detach the survivor’s memories and hopes from the dead’ (SE 13, p. 65).

All the studies available suggest that most women take a long time to get over the death of a husband and that, by whatever psychiatric standard they are judged, less than half are themselves again at the end of the first year. Almost always health suffers. Insomnia is near universal; headaches, anxiety, tension and fatigue extremely common. In any one mourner there is increased likelihood that any of a host of other symptoms will develop; even fatal illness is more common than it is in non-bereaved people of the same age and sex (Rees and Lutkins 1967; Parkes et al. 1969; Ward 1976). To do justice to the important issue of the impaired physical health of bereaved people would require a chapter to itself and would take us too far from the topics of this volume. The reader is therefore referred to the above papers and also to the following: Parkes (1970c); Parkes and Brown (1972); Maddison and Viola (1968).

As regards duration of mourning, when Parkes interviewed the twenty-two London widows at the end of their first year of bereavement, three were judged still to be grieving a great deal and nine more were intermittently disturbed and depressed. At that time only four seemed to be making a good adjustment.

Findings of the Harvard study (Glick et al. 1974) were rather more favourable. Even though a majority of the 49 Boston widows were still not feeling wholly themselves again at the end of the first year, four out of five seemed to be doing reasonably well. Several described how at a particular moment during the year they had asserted themselves in some way and had thereafter found themselves on a path to recovery. Deciding to sort through husband’s clothes and possessions, itself an intensely painful task, had for some been the turning-point. For others it had followed a sudden and prolonged fit of crying. Although consulting husband’s wishes continued to influence decisions, by the end of the year his wishes were less likely to be the dominant consideration. During the second and third years the pattern that a widow’s reorganized life would take, in particular whether she would remarry, seemed firmly established. Except for those on the road to remarriage, however, loneliness continued a persistent problem.

In contrast to the majority of Boston widows who were making progress, there was a minority who were not. Two became seriously ill, one dying; and six continued disturbed and disorganized. The impression was gained that if recovery was not in progress by the end of the first year prognosis was not good.

From these and other findings it must be concluded that a substantial minority of widows never fully recover their former state of health and well-being. A majority of those who do, or at least come near to it, are more likely to take two or three years to do so than a mere one. As one widow in her mid-sixties put it five years after her husband’s death: ‘Mourning never ends: only as time goes on it erupts less frequently.’ Indeed, an occasional recurrence of active grieving, especially when some event reminds the bereaved of her loss, is the rule. I emphasize these findings, distressing though they are, because I believe that clinicians sometimes have unrealistic expectations of the speed and completeness with which someone can be expected to get over a major bereavement. Research findings, moreover, can be very misleading unless interpreted with care. For at one interview a widow may report that at last she is progressing favourably yet had she been interviewed a few months later, after she had met with some disappointment, she might have presented a very different picture.

Reference has been made more than once to the deep and persisting sense of loneliness that the bereaved so commonly suffer and which remains largely unalleviated by friendships. Although for long noted at an empirical level, for example by Marris (1958), this persistent loneliness has tended to be neglected at a theoretical level, largely perhaps because social and behavioral scientists have been unable to accommodate it within their theorizing. Recently, however, thanks largely to the work of Robert S. Weiss of Harvard, it is receiving more attention.

Weiss, a sociologist who participated in the Harvard bereavement study (with Glick and Parkes), has carried out another study, this time into the experiences of marital partners after they had become separated or divorced (Weiss 1975b). In order better to understand the problems of such people he worked in a research role with an organization, Parents without Partners, designed to give them a meeting-place. Friendly interaction with others in the same plight would, it had been expected, compensate them in their loss, at least in some degree. But it proved otherwise: ‘. . . although many members, particularly among the women, specifically mentioned friendship as a major contribution of the organization to their well-being, and although these friendships often became very close and very important to the participants, they did not especially diminish their loneliness. They made the loneliness easier to manage, by providing reassurance that it was not the individual’s fault, but rather was common to all those in the individual’s situation. And they provided the support of friends who could understand’ (Weiss 1975a, pp. 19–20).

As a result of these and similar findings Weiss draws a sharp distinction between the loneliness of social isolation, for mitigating which the organization proved useful, and the loneliness of emotional isolation, which went untouched. Each form of loneliness, he believes, is of great importance but what acts as remedy for one does not remedy the other. Couching his thinking in terms of the theory of attachment outlined in these volumes, he defines emotional loneliness as loneliness that can be remedied only by involvement in a mutually committed relationship, without which he found there was no feeling of security. Such potentially long-term relationships are distinct from ordinary friendships and, in adults of Western societies, take only a few forms: ‘Attachment is provided by marriage, by other cross-sex committed relationships; among some women by relationships with a close friend, a sister or mother; among some men by relationships with “buddies”’ (Weiss 1975a, p. 23).

Once the nature of emotional loneliness is understood its prevalence among widows and widowers who do not marry again, and also among some who do, is hardly surprising. For them, we now know, loneliness does not fade with time.

Of the various studies drawn upon in this chapter only one, the Harvard study, gives sufficient data for tentative conclusions to be drawn between the course of mourning in widows and in widowers (Glick et al. 1974). Two other studies, by Rees (1971) and Gorer (1965), provide additional data which, so far as they go, support those conclusions.

The initial size of the Harvard sample was 22 widowers; of these 19 were available at the end of the first year and 17 at the end of about three years. Despite small numbers all levels of socio-economic life were represented and so were the major religious and ethnic groups. Like the Boston widows, all widowers were under the age of 45 at the time of bereavement.

Comparing the responses of the widowers with those of the widows the researchers conclude that, although the emotional and psychological responses to loss of a spouse are very similar, there are differences in the freedom with which emotion is expressed and differences also in the way in which attempts are made to deal with a disrupted social and working life. Many of these differences are not large but they appear consistent.

Let us start with the similarities. There were no differences of consequence in the percentages of widows and widowers who, during the first interviews, described pain and yearning and who were tearful. The same was true of their experiencing strong visual images of the spouse and a sense of his or her presence. At the end of the first year, although rather fewer widowers described themselves as being at times very unhappy or depressed, the difference was still small, namely widows 51 per cent and widowers 42 per cent. The proportions who claimed that, after a year, they were beginning to feel themselves again was, similarly, tilted only slightly in favour of the widowers, namely widows 58 per cent and widowers 71 per cent. When at a year the condition of widowers was compared to that of a control group of married men, a larger proportion of them than of the widows seemed to have been adversely affected by the bereavement, the widows being judged, similarly, by comparing their condition with that of members of a control group of married women.7 The widowers at that stage seemed to suffer especially from tension and restlessness. Fully as many widowers as widows reported feeling lonely.

In expressing their sense of loss widowers were more likely to speak of having lost a part of themselves; in contrast, widows were more likely to refer to themselves as having been abandoned. Yet both forms of expression were used by members of both sexes and it remains uncertain whether or not such difference as was noted is of psychological significance.

Turning now to the differences, it was found that, at least in the short term and during interviews, widowers tended to be more matter-of-fact than widows. For example, eight weeks after bereavement, whereas all but two of the widowers gave the impression of having accepted the reality of the loss, only half the widows gave that impression: the other half were not only on occasion acting as though their husbands were still alive but also were sometimes feeling he might actually return. In addition a larger proportion of widows than widowers were fearing they might have a nervous breakdown (50 per cent of widows and 20 per cent of widowers) and were likely still to be rehearsing the events leading to their spouse’s death (53 per cent of widows and 30 per cent of widowers).

In keeping with their matter-of-fact attitude fewer widowers admitted to feeling angry. During the first two interviews the proportion of widows clearly expressing anger varied between 38 and 52 per cent, the proportion of widowers between 15 and 21 per cent. Taking the year as a whole 42 per cent of the widows were rated as having shown moderate or severe anger compared with 30 per cent of the widowers. In regard to feelings of guilt, however, the picture was equivocal. Initially self-reproach was evident in a higher proportion of widowers than widows; but subsequently the proportions reversed.

It is likely that some of these differences stem from a greater reluctance of widowers than widows to report their feelings. Whether this was so or not, there was no doubt that many of the widowers regarded tears as unmanly, and that more of them therefore attempted to control expression of feeling. In contrast to the widows, a majority of widowers disliked the idea of some sympathetic person encouraging them to express feeling more freely. Similarly, a greater proportion of widowers tried deliberately to regulate the occasions when they allowed themselves to grieve. This they did by choosing the occasions when they would look at old letters and photographs and avoiding reminders at other times. In keeping perhaps with this tendency to exert control over feeling was the dismay expressed by some of the widowers that their energy and competence at work should have become as reduced as it often was.

Most widowers welcomed any assistance given by their female relatives in caring for house and children, and were relieved at the chance to carry on with their work much as before.

A sense of sexual deprivation was much more likely to be reported by widowers than widows; and, in contrast to the marked reluctance of about one-third of the widows even to consider remarriage, a majority of widowers moved quickly to think of it. By the end of a year half of them had either already remarried or appeared likely to do so soon (in comparison with only 18 per cent of widows). At the time of the final interview half had in fact remarried (in comparison with a quarter of the widows). A majority of these second marriages appeared to be satisfactory. In some it was a tribute to the second wife who was willing not only for her husband to remain a good deal preoccupied with thoughts of his first wife but to engage with him often in talking about her.

Although after two or three years a majority of widowers had reshaped their lives reasonably successfully, there was a minority who had failed to do so. For example, there were then not less than four widowers who were either markedly depressed or alcoholic or both. One had made an impulsive remarriage which had ended as soon as it had begun. Another, who had had a breakdown before marriage and who had lost his wife very suddenly from a heart attack, remained deeply depressed and unable to organize his life. All four had had no forewarning of their wife’s death.

The purpose of this note is to describe the various studies listed in Table 1 in rather more detail than is convenient in the text of the chapter. Because of my indebtedness to the studies undertaken in London and Boston by my colleague, Colin Murray Parkes, we start with some particulars of those.

In the first of his two studies Parkes set out to obtain a series of descriptive pictures of how a sample of ordinary women respond to the death of a husband. To this end he interviewed, personally, a fairly representative sample of 22 London widows, aged between 26 and 65, during the year following bereavement. The sample was obtained through general practitioners who introduced the research worker to the subjects. Each widow was interviewed on at least five occasions-the first at one month after bereavement and the others at three, six, nine and twelve-and-a-half months after. Interviews, held in the widow’s own home in all but three cases, lasted from one to four hours. At the start of each, general questions were put to encourage the widow to describe her experiences. Only when she had finished did the interviewer ask additional questions either to cover areas she had not mentioned or to enable ratings to be made on scales designed in the light of previous work. By proceeding in this way good rapport was established so that information was given frankly and intense feeling often expressed. Most of the widows regarded their participation in these interviews as having been helpful to themselves, and some of them welcomed the suggestion of additional interviews.

Details of the sample, the ground covered in the interviews and the probable reliability of assessments are given in Parkes (1970a). Subjects were drawn fairly evenly from the various social classes, and ranged in age for 26 to 65 years (average 49 years). All but three had children. The commonest causes of the husband’s death were cancer (ten cases) and cardiovascular disease (eight). Most of the husbands had died in hospital and without their wife being present; eight had died at home. Nineteen widows had been warned of the seriousness of their husband’s condition, thirteen of them at least one month before the end. The final deterioration and death was foreseeable for at least a week in nine cases, for some hours in three but had come suddenly in nine.

The second study was initiated at the Harvard Laboratory of Community Psychiatry in Boston by Gerald Caplan. Subsequently, Parkes was invited to join the team and later took over responsibility for the study which came to be known as the Harvard Bereavement Project. Its aim was to devise methods for identifying, soon after bereavement, those subjects who are likely to be at higher than average risk of responding to loss in a way unfavourable to their mental and physical health.

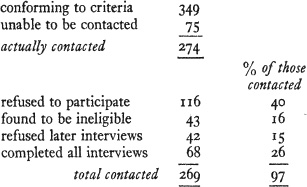

Because it was believed that bereaved subjects under the age of 45 years are more likely than older subjects to have an adverse outcome to their mourning the sample studied were all under that age. Those who completed all interviews numbered 49 widows and 19 widowers and represented 25 per cent of the 274 men and women of appropriate age in the community selected who had lost a spouse during the relevant period and who could be contacted. (40 per cent refused to participate and 16 per cent proved unsuitable because of language, distance or other problems. A further 15 per cent dropped out of the study during the first year of bereavement, a major reason being their unwillingness to review painful memories.)8

Three weeks after bereavement and again six weeks later widows and widowers were interviewed in their homes by experienced social workers. Each interview lasted between one and two hours and was tape-recorded. The next interviews were not until thirteen months after bereavement when two further interviews were conducted. In the first of these, which proceeded on lines similar to the earlier ones, a detailed account of the events of the preceding year and of the respondent’s present condition was obtained. In the second a fresh interviewer, who was unknown to the respondent and who himself had no knowledge of the previous course of events, administered a questionnaire; this, constructed in terms of forced-choice questions, was aimed to give independent and clear-cut measures of the respondent’s current state of health. By relating these measures of outcome at thirteen months to information obtained at three and six weeks, it was hoped to discover what features present during the early weeks of bereavement are indicative of favourable or unfavourable outcome later. As a final step a follow-up interview was conducted by a social worker between one and three years later, namely between two and four years after the death. All but six widows and two widowers were able to participate at this stage, giving a sample of 43 widows and 17 widowers.

Details of the sampling, of the methods of coding the interview material and of devising outcome measures, and estimates of the reliability of such measures, can be found in the two volumes in which the findings are published (Glick, Weiss and Parkes 1974, second volume in preparation). In nearly half the cases death had been sudden, due to accident or heart, or else had occurred without much warning. In most of the remainder deaths followed illnesses of obvious severity ranging in duration from several weeks to years. How much forewarning a bereaved person is given is found to be related in considerable degree both to the capacity of the bereaved to recover from the loss and also to the form recovery takes, matters to which much more attention will have to be paid in future than has been given hitherto.

In addition to these studies we draw on the findings of several other studies of widows and of some which included widowers also. All of them differ from the London and Harvard studies in a number of ways and, by so doing, complement their findings in certain respects. For example, two of them, by Hobson (1964) and by Rees (1971), were conducted outside urban settings; and in both cases the researcher managed to interview almost every one of the bereaved subjects who fell within the initial sampling. In all but one of these additional studies interviewing was done at least six months, and usually a year or more after the loss had occurred, thus giving good coverage of later phases of mourning at the price of poor coverage of the earlier ones.

The first of these additional studies is the pioneer study by Marris (1958), a social psychologist. His aim was to interview all women who had been widowed during a certain two-and-a-quarter-year period whilst living with their husbands in a working-class district of London and whose husbands had been 50 years old or under at death. Of the total of 104 such widows, 2 had died, 7 were untraceable, 7 had moved away and 16 refused, leaving a total of 72 who were interviewed. Their bereavement had occurred from one to three years earlier, in the main about two years. Their ages ranged from 25 to 56 years with an average of 42 years, and the duration of their marriages ranged from one to thirty years, with an average of sixteen years. All but eleven had children living, the children being of school age or less in the case of 47. Interviews covered not only a widow’s emotional experiences but also her current financial and social situation.

A rather similar study was conducted by Hobson (1964), a social-work student, who interviewed all but one of the widows in a small English market-town who were under the age of sixty and who had lost their husband not less than six months and not more than four years earlier. Her interview method was similar to Marris’s, though briefer. The number interviewed was forty; their ages ranged from 25 to 58 years (the majority being over 45 years). All but seven had been married for ten years or longer; and the husbands of all but five had been working class, either skilled or unskilled.

In an attempt to learn more of the health problems of widows Maddison and Viola (1968) studied 132 widows in Boston, U.S.A., and 243 in Sydney, Australia. The main studies were conducted by questionnaire. In Boston the age of husbands at death lay between 45 and 60; in Sydney the lower age-limit was abandoned. Since in both cities refusal rates were about 25 per cent and another 20 per cent proved untraceable, those questioned reached only about 50 per cent of the total aimed for. The questionnaire was designed to give basic demographic data and the widows’ responses to 57 items which reviewed her physical and mental health over the preceding 13 months, with special reference to complaints and symptoms which were either new or substantially more troublesome during the period. In each city a control group of non-bereaved women was also studied.

Maddison’s studies, both in Boston and in Sydney, have a second part. In each city a sub-sample of widows whose health reports showed they were doing badly and a sub-sample of those doing well, matched as closely as possible on socio-economic variables, were interviewed. The aims were, first, to check on the validity of the questionnaire, which proved satisfactory, and secondly to cast light on factors associated with a favourable or an unfavourable outcome. Findings, which are drawn on in Chapter 10, are reported in Maddison and Walker (1967) and Maddison (1968) for Boston, and in Maddison, Viola and Walker (1969) for Sydney. The work in Sydney has been extended by Raphael (1974, 1975; Raphael and Maddison 1976); particulars are given in Chapter 10.

Another study, also with a focus on health, was conducted by a team in St Louis, Missouri (Clayton et al. 1972, 1973; Bornstein et al. 1973). The sample comprised 70 widows and 33 widowers, who represented just over half those approached. Ages ranged very widely from 20 to 90 years, with a mean of 61 years. Interviews were conducted about thirty days after bereavement and again at four months and at about thirteen months. In a quarter of the cases death had been sudden, namely five days of forewarning or less. In 46 forewarning was six months or less and in the remaining 35 more than six months. Whenever forewarning was sufficient spouses were interviewed also before the death had occurred. A serious limitation of this study was that interviews were restricted to an hour’s duration.

Another study including widowers as well as widows, but with a different focus, was conducted by Rees (1971), a general practitioner, who interviewed all the men and women who had lost a spouse and were resident in a defined area of mid-Wales, omitting only those who were suffering from incapacitating illness and a mere handful of others. The total numbers interviewed were 227 widows and 66 widowers, who ranged widely in age with most between forty and eighty. In this study interviews were concerned especially to determine whether the widowed person had experience of illusions (visual, auditory or tactile, or a sense of presence) or hallucinations of the dead spouse.9 He found them to be far more common than might formerly have been supposed.

There is at least one other study which reports on responses to loss of spouse, although here widows and widowers make up only a minority of the sample. This is by Gorer (1965, 1973), a social anthropologist who interviewed eighty bereaved people selected to cover persons of all ages over 16 years and both sexes who had lost a first-degree relative within the previous five years and to cover also a wide range of social and religious groups throughout the United Kingdom. Since some of those interviewed had lost more than one relative and tables are incomplete exact numbers are not available. Included are some twenty widows, of ages varying from 45 to over 80, and nine widowers, of ages from 48 to 71. (Of others interviewed, thirty or more had lost a mother or father during adult life, a dozen had lost a sibling, and others had lost a son or daughter.) Gorer’s principal interest is the social context in which death and mourning take place and the social customs or lack of them obtaining in twentieth-century Britain. Because in regard to any one class of bereaved people samples are small, it is not possible to know how representative his findings are. Nevertheless, his book, which contains many vivid transcripts of how bereaved people describe their experience, is of great psychological interest.

1 In an earlier paper (Bowlby 1961b) it was suggested that the course of mourning could be divided into three main phases, but this numbering omitted an important first phase which is usually fairly brief. What were formerly numbered phases 1, 2 and 3 have therefore been renumbered phases 2, 3 and 4.

2 In concentrating on these aspects of mourning we are able to give only limited attention to the social and economic consequences of a bereavement, which are often also of great importance and perhaps especially so in the case of widows in Western cultures. Readers concerned with these aspects are referred to the accounts of Marris (1958) and Parkes (1972) for the experiences of London widows and to that of Glick et al. (1974) for those of Boston widows.

3 Traditionally the term ‘denial’ has been used to denote disbelief that death has occurred; but ‘denial’ always carries with it a sense of active contradiction. Disbelief is more neutral and better suited for general use, especially since the cause of disbelief is often inadequate information.

4 Behaviour influenced by an expectation of ultimate reunion is observed in many women with a husband who has deserted or whose marriage has ended in divorce. Marsden (1969) studied eighty such women, all with children, and dependent on the State for support, a great number of whom had not lived with their husband for five years or more. Remarking on the striking resemblance of the responses shown by some of them to responses seen after a bereavement, Marsden writes (p. 140): ‘The mother’s emotional bonds with the father did not snap cleanly with the parting. Almost half the mothers, many of whom had completely lost touch with the father, had a sense of longing for him . . . It was evident that a sizable minority of women persisted, in spite of evidence to the contrary and sometimes for many years, in thinking they would somehow be reunited with their children’s father.’ After having moved into a new house three years earlier one of them had still not unpacked her belongings, unable to believe the move was permanent.

5 There is some evidence that the incidence of anger varies with the sex of the bereaved and also with the phase of life during which a death occurs. For example, findings of the Harvard study, which show an even higher incidence of anger among widows, show a lower incidence among widowers (see p. 43); and Gorer (1965) believes it to occur less frequently after the death of an elderly person—a timely death—than after that of someone whose life is uncompleted. The low incidence of anger reported by Clayton et al. (1972) may perhaps be a result of their sample being both elderly and also made up of one-third widowers.

6 Early in his work Freud (1916) had remarked on the way a dream can express incompatible truths: ‘When anyone has lost someone near and dear to him, he produces dreams of a special sort for some time afterwards, in which knowledge of the death arrives at the strangest compromises with the need to bring the dead person to life again. In some of these dreams the person who has died is dead and at the same time still alive . . . In others he is half dead and half alive’ (SE 15, p. 187).

7This finding is difficult to interpret, however, because the married women controls were found to be appreciably more depressed than their male counterparts.

8 As a proportion of all those conforming to the sampling criteria, the final sample was derived as follows:

The proportions of widowers and widowers respectively affected by these reductions are similar. (These figures, derived from Table One in Glick et al. (1974), leave five cases unaccounted for.)

9 Contrary to Rees’s own account the great majority of the experiences reported by him appear to have been illusions, namely misinterpretations of sensory stimuli; and not hallucinations.