And while that face renews my filial grief,

Fancy shall weave a charm for my relief

Shall steep me in Elysian reverie,

A momentary dream, that thou art she.

WILLIAM COWPER1

WHEN WE READ the evidence presented by Furman (1974) and the other workers named, it seems clear that provided conditions are favourable even a young child is able to mourn a lost parent in a way that closely parallels the healthy mourning of adults. The conditions required are no different in principle to the conditions that are favourable for adult mourning. Those most significant for a child are: first, that he should have enjoyed a reasonably secure relationship with his parents prior to the loss; secondly that, as already discussed, he be given prompt and accurate information about what has happened, be allowed to ask all sorts of questions and have them answered as honestly as is possible, and be a participant in family grieving including whatever funeral rites are decided on; and, thirdly, that he has the comforting presence of his surviving parent, or if that is not possible of a known and trusted substitute, and an assurance that that relationship will continue. Admittedly, these are stringent conditions but before dwelling on the many difficulties of meeting them let us describe the way children and adolescents commonly respond when the conditions can be met.

Evidence shows that after a parent’s death a child or adolescent commonly yearns as persistently as does an adult and is ready to express such yearning openly whenever a listener is sympathetic. At times he entertains hope that his lost parent will return; at others he recognizes reluctantly that that cannot be and is sad. On occasion he will be observed searching (though this feature is not well recorded in the literature), or will describe experiencing a vivid sense of the dead person’s presence. In some circumstances he will feel angry about his loss and in others guilty. Not infrequently he will be afraid that he will also lose his surviving parent, and/or substitute-parent, or that death will claim him too. As a result of his loss and his fear of further loss he will often be anxious and clinging, and sometimes engage obstinately in behaviour that is difficult to understand until its rationale is known.

To move from generalization to individual case there follow accounts of two children both recorded in great detail by Marion J. Barnes, a member of the group headed by Robert and Erna Furman in Cleveland. The records have been selected because they are the most complete available of young children from stable homes who have been developing reasonably well and have then suddenly lost a parent.2 One, Wendy, lost her mother when she had just turned four. The other, Kathy, lost her father when she was two months younger. The reason for examining first the responses of children at the lower end of the age-range is that the younger the child the less likely, it has been supposed, is his mourning to resemble that of an adult.

Wendy was aged four years when her mother died in an acute exacerbation of a chronic illness. Thereafter Wendy lived with her father and her sister, Winnie, eighteen months younger. In addition, maternal grandmother made herself responsible for the children’s care whilst father was at work, and a maid who had been a daily with the family since the children were infants now became resident for five days a week. Help was given at weekends by paternal grandmother and another maid.

Much information is available about Wendy’s development prior to her mother’s death because for eighteen months mother had been coming for weekly professional advice on account of what appear to have been, in a two-and-a-half-year-old, rather minor problems. Wendy is described as wetting her bed, to have been attached to a blanket, to have had ‘some typical fantasies around penis envy’, and to have been unable to express her hostility in words, particularly toward her younger sister. Six months later mother was still concerned about Wendy’s attachment to the blanket, her thumb sucking and her reluctance to separate from her. In other respects, however, Wendy seemed to be making good progress and began attending a nursery school.

It then transpired that Wendy’s mother, now twenty-five, had had an attack of multiple sclerosis which had been in remission during the previous seven years. Apart from mother’s two-hour-long daily rest periods, however, the illness made no outward difference to the family and both parents were keen to keep it dark, though not unexpectedly Wendy often resented having to keep quiet during mother’s long rests. When information about the illness finally emerged the therapist felt it advisable as a precautionary measure for Wendy to be transferred to the clinic’s therapeutic nursery school; but no one anticipated that tragedy was so close. For within four months of Wendy starting there, her mother had a fulminating flare-up of the illness, entered hospital suddenly and died within two weeks.

During the week or two prior to the acute attack mother was inclined to feel fatigued and had a pain in her shoulder. Wendy was worried and became reluctant to attend nursery school, especially when it meant father taking her there instead of mother. She was clearly worried about mother’s being unwell; and her anxiety was increased by the paternal grandfather, whom they visited almost daily, being seriously ill also and not expected to live.

When mother’s condition suddenly became worse and she was admitted to hospital, the therapist saw father daily to help him decide what to tell the children. On her advice the illness was explained to them as being very serious, so serious in fact that mother could not lift her head and arms or even talk, which helped Wendy understand why mother could not talk to her on the phone. The children were also told that the doctors were doing everything possible to help. During the last critical days, moreover, the therapist suggested to father that he not hide completely from them his sadness, concern and anxiety, as he had previously felt he must.

During the weeks prior to the flare-up of the illness, Wendy was expressing some hostility and rivalry towards mother and also expressed a fear on two occasions that mother might die. Basing her interventions on the theory that a child’s fear of mother’s death is commonly a result of an unconscious wish that she should die, the therapist encouraged the parents to reassure Wendy that her occasional angry thoughts would not affect mother’s well-being. During the acute phase of mother’s illness father was encouraged to continue giving such reassurances.3

On the day mother died father decided to tell the children what had happened, and also that mother would be buried in the ground and that this was the end. This he did during a ride in the car. Mother had stopped breathing, he told them, she could not feel anything; she was gone for ever and would never come back. She would be buried in the ground, protected in a box and nothing would hurt her—not the rain nor the snow (which was falling) nor the cold. Wendy asked, ‘How will she breathe and who will feed her?’ Father explained that when a person is dead they don’t breathe any more and don’t need food. There had already been general agreement that the children were too young to attend the funeral; but father showed them the cemetery, with a near-by water tower which could be seen from their window.

That evening the children seemed relatively unaffected and for a time were busy playing ‘London Bridge is falling down’. Relatives, who disagreed with father’s candour and preferred to tell the children stories of heaven and angels, endeavoured to stifle their sorrow and to enter gaily into the children’s games.

During the days that followed Wendy invented two games to play with her father, in both of which she would twirl around and then lie down on the floor. In one she would then quickly stand up with the remark ‘You thought I was dead, didn’t you?’ In the other, in which she was supposed to rise when father gave the proper signal (which was her mother’s first name), she remained prone. There were also occasions, for example at meals, when Wendy cheerfully enacted the part of her mother with remarks such as ‘Daddy, this is such a pretty tie. Where did you get it?’ or ‘Anything interesting happen at the office today?’

Yet sorrow was not far away. A week after mother’s death the grandmother of another child became very emotional when talking about it in the car to Wendy’s grandmother. Wendy paled and fell over on the seat. Grandmother comforted her, held her and they both cried. About the same time, on a visit to relatives, cousins assured Wendy her mother was an angel in heaven and then showed her her mother’s picture. Wendy cried hysterically and said her mother was in the ground.

During the third week after mother’s death Wendy gave evidence that she was still hoping for mother’s return. Sitting on the floor with her younger sister, she chanted, ‘My mommy is coming back, my mommy is coming back, I know she’s coming back.’ To this Winnie retorted in an adult-like monotone, ‘Mommy’s dead and she’s not coming back. She’s in the ground by the “tower water”.’ ‘Tsh, don’t say that,’ retorted Wendy.

Wendy’s preoccupation with her mother was shown too in a ‘snowflake’ song she had made up on the day after the funeral. At first it ran (probably influenced by the interpretations she had received): ‘Snowflakes come and they disappear. I love my mommy and she is dead. I hate my mommy and I hope she doesn’t come back. I love my mommy and I want her.’ A few days later she omitted ‘I hate my mommy’. By the sixth day it was in the past tense, ‘I loved my mommy and want her to come back.’ A fortnight later on the way to school it was ‘My mommy is coming back’, but whispered so low that grandmother could hardly hear it.

The same preoccupation emerged from another concern of Wendy’s. Almost daily on the way to school she engaged her grandmother in conversation about the ducks on the pond: ‘Are they cold? Will they freeze? Who feeds them?’ At times these discussions merged into more direct questions: ‘Do dead people have to be fed? Do they have any feelings?’ To rebut information given by grandmother that freezing temperatures result in even thicker ice, Wendy would point hopefully to a small area over a spring; ‘But, Grandma, I see a little part that is not frozen even though it is so cold.’ The therapist suggested to grandmother she discuss with Wendy how very hard it is to believe that a person is dead for ever and will never return.

After one such talk Wendy decided to pretend that grandmother was mother—she would call her Mommy and grandmother was to pretend that Wendy was her own little girl. At nursery school she told another child how she had a mother for pretend—her grandmother. To this the other child remarked. ‘Oh, it really isn’t the same, is it?’ to which Wendy assented sadly, ‘No, it isn’t.’

On another occasion, about four weeks after mother had died, Wendy complained that no one loved her. In an attempt to reassure her, father named a long list of people who did (naming those who cared for her). On this Wendy commented aptly, ‘But when my mommy wasn’t dead I didn’t need so many people—I needed just one.’

Four months after mother’s death, when the family took a spring vacation in Florida, it was evident that Wendy’s forlorn hopes of mother’s return persisted. Repeating as it did an exceptionally enjoyable holiday there with mother the previous spring, Wendy was enthusiastic at the prospect and during their journey recalled with photographic accuracy every incident of the earlier one. But after arrival she was whiny, complaining and petulant. Father talked with her about the sad and happy memories the trip evoked and how very tragic it was for all of them that Mommy would never return; to which Wendy responded wistfully, ‘Can’t Mommy move in the grave just a little bit?’

Wendy’s increasing ability to come to terms with the condition of dead people was expressed a year after mother’s death when a distant relative died. In telling Wendy about it father, eager not to upset her, added that the relative would be comfortable in the ground because he would be protected by a box. Wendy replied, ‘But if he’s really dead, why does he have to be comfortable?’

Simultaneously with her persisting concern about her missing mother and the gradually fading hopes of her return, Wendy gave evidence of being afraid she herself might die.

The first indications were her sadness and reluctance to go to sleep during nursery school naptime. Her teacher, sensing a problem, took Wendy on her lap and encouraged her to talk. After some days Wendy explained how, when you are asleep, ‘You can’t get up when you want to.’ Six months later she was still occupied with the distinction between sleep and death, as became plain when a dead bird was found and the children were discussing it.

Wendy’s fear of suffering the same fate as her mother manifested itself also when, during the fourth week after mother’s death, she insisted that she did not want to grow up and be a big lady and that, if she had to grow up, she wished to be a boy and a daddy. She also wanted to know how old one is when one dies and how one gets ill. On the therapist’s encouragement father talked with Wendy about her fear that when she grew up she would die as her mother had and also reassured her that mother’s illness was very rare. A few days later Wendy enquired of her grandmother, ‘Grandma, are you strong?’ When grandmother assured her she was, Wendy replied, ‘I’m only a baby.’ This provided grandmother with further opportunity to discuss Wendy’s fear of the dangers of growing up.

On another occasion when Wendy was similarly afraid, the clues were at first sight so hidden that her behaviour appeared totally unreasonable. One morning during the third week after mother’s death Wendy, quite uncharacteristically, refused to put on the dress decided upon or go to school and, when the maid persisted, threw a temper tantrum. The family were puzzled, but they hit on the solution whilst discussing the incident with the therapist. Before Christmas mother had taken the children to look at the shops and in one they had seen Santa Claus attended by little angels. The angels’ dresses were for sale and mother had bought one for each of the children who were delighted. It was her angel dress that Wendy had objected to wearing that morning.

A fortnight after this episode paternal grandfather died. When told, Wendy was matter-of-fact about the funeral and seemed to comprehend well the finality of death. At nursery school she was sad, and whilst sitting on the teacher’s lap, she told about the death and cried a little; but then claimed she was only yawning. A little later, however, she commented, ‘It’s all right to cry if your mother and grandfather died.’ Thereafter she recalled nostalgically how when first she came to nursery school her mother was not sick and would take her to and from school.

Shortly afterwards, hearing someone mention that grandfather’s house would be sold, Wendy became apprehensive. She refused to go to school and, instead, stayed to check on the dishes and chairs at home. Only after it was explained that her house was not to be sold as well were her fears allayed and was she willing to go to school again.

There were many occasions when Wendy was afraid lest she lose other members of her family. For example, she was often upset and irritable at nursery school on Monday mornings. When asked what troubled her she replied that she was angry because her maternal grandmother and the maid had not been with her at the week-end. She did not want them to leave—ever. In the same way she was angry with her grandmother when, nine months after mother’s death, she finally took a few days’ break.

On two occasions father was away overnight on business trips. At school Wendy seemed sad and, when the teacher asked what she would like her to write, replied, ‘I miss my mommy.’ On the second occasion she did not want grandmother to leave her at nursery school, got out her old blanket and sat next to the teacher. Later she cried and agreed that she missed her father and was worried lest he not return. In a similar way she was upset when the maid was away for five weeks because of a leg injury. When at last the maid returned, Wendy wanted to stay at home with her instead of going to school.

Much else in the record shows Wendy’s persistent longing for mother and her constant anxiety lest she suffer some other misfortune. When a new child arrived at school Wendy would look sad as she watched the child with her mother. On one such occasion she claimed that her mother was going to wash her face because the maid had forgotten to. Any small change of routine such as her teacher being away would be met with anxiety. On such occasions instead of playing she would sit with another teacher looking sad.

At the end of twelve months Barnes reports that Wendy was progressing well but predicted that, as in the year past, separations, illness, quarrels and the deaths of animals or people would continue to arouse in Wendy ‘a surplus’ of anxiety and sorrow.

In Chapter 23 an account is given of how two-and-a-half-year-old Winnie responded after her mother’s death.

Kathy was aged 3 years and 10 months when her father died very suddenly of a virus infection. Thereafter she lived in the house of the maternal grandparents with her mother and two brothers, Ted aged five and Danny not quite one.

Before the tragedy the family had been known to the therapist for about eighteen months because the parents, ‘a happy young couple devoted to each other and to their children’, had sought advice about Ted’s overactive behaviour. After a few sessions, which led to changes in the parents’ handling of him, Ted’s behaviour improved. A few weeks after father’s death, however, mother was again worred about Ted and sought further advice.

At the time of father’s illness and death all members of the family had been ill and the baby, Danny, had been admitted to hospital at the same time as father. After father died mother, shocked and distraught, immediately shared the news with Ted and Kathy and took them to stay with her own parents. After the funeral, which the children did not attend, mother sold the house and went to live with her parents, remaining at home herself to care for the children.

From babyhood onwards Kathy’s development had been favourable. She talked early, dressed herself with great pride by two years, and enjoyed helping mother in the house. Until she was two and a half she had sucked a forefinger and was also attached to a blanket, but had then lost interest. Now in her fourth year she enjoyed cooking with mother and making the beds. She was very handy with paste and scissors, could concentrate for long periods of time and took great pleasure in achievement. Soon after her birth she had become ‘father’s openly acknowledged favourite’ and when he returned from work he had always picked her up first.4

After father died Kathy’s life changed abruptly. Not only had she no father but mother was preoccupied and her brothers also upset. Moreover it was a new house, grandfather preferred the boys and grandmother was not very tolerant of young children. Kathy often cried and was sad; she lost her appetite, sucked her finger and resumed cuddling her blanket. At other times, however, she asserted ‘I don’t want to be sad’ and seemed even a little euphoric.

Although mother mourned deeply, she had difficulty expressing her feelings and there was reason to think her reserve interacted with Kathy’s own tendency to overcontrol. When mother, with some help, found herself able to share feeling with the children, to talk to them about father and to assure Kathy it was in order to be sad, Kathy’s euphoria abated. Nevertheless, in view of her tendency to overcontrol, the therapist thought it desirable for her to be transferred to the clinic’s nursery school. This was five months after father’s death when Kathy was 4 years and 3 months old. Mother continued to have weekly talks with the therapist.

During the early weeks at school Kathy seemed to be in complete control. She adapted quickly to the new routines, wished to stay for longer each day and expressed few feelings of missing her mother. She did not make close relationships with other children or teachers, however, and was apt to appeal unnecessarily to the teachers instead of fighting her own battles.

From the first Kathy spoke about her father and told everyone immediately that he had died. When, on the third day of her attendance, a turtle died she insisted on removing it from the tank (into which another child had put it) and demanded it be buried. It appeared that she had a good understanding of the concrete aspects of death, even if she expressed no feeling. Yet, significantly enough, she was at this time much concerned about the welfare of another child who had also lost his father. By comforting him and amusing him she tried hard to distract him from his sorrows.

Three months after starting school Kathy for the first time visited her father’s grave. She was in a conflict about going. She both wanted to go and also cried bitterly about doing so. After placing flowers on the grave she began asking a succession of questions that mother found painful to answer: ‘Are there snakes in the ground? Has the box come apart?’ Mother struggled bravely to help Kathy to understand and express her feelings but sometimes found the burden too great.

During the following four months Kathy, already aged 4½ years, had a difficult time. Danny was now very active and required mother’s constant vigilance. Ted, with whom Kathy had regularly played, now preferred his peers. Grandfather’s preference for the boys was unmistakable. And finally Kathy, who had had a minor orthopaedic problem, now required a cast on one leg. No longer was she the happy controlled little girl. Evidently feeling left out, she became demanding of the teachers and irritable and petulant with her mother. Her play deteriorated; she refused to share her toys and became generally cranky and miserable. Either she showed off by endlessly dressing up in fancy clothes and jewellery or else withdrew into herself. Masturbation increased and so did her demand for her blanket. At night she insisted her mother reassure her that she loved her.

Throughout these later months Kathy frequently expressed intense longing for her father. Both at home and at school she talked about him and described all the activities they engaged in together; sometimes she recounted stories in which father rescued her when she was scared and alone. At Christmas when the family visited the grave Kathy was deeply sad and wished for her father’s return. When asked what she wanted as a Christmas present, she replied dejectedly, ‘Nothing.’

During this time Kathy was often angry and unreasonable with her mother, especially over minor disappointments. For example, on one occasion mother had promised her sledding after school but had had to cancel it because the snow had melted. Kathy, inconsolable, reproached her mother bitterly as she had on similar occasions previously: ‘I can’t stand people breaking their promises.’ Subsequently it transpired that, on the day before his admission to hospital, father had promised to take Kathy to the candy store on the following day and inevitably had failed to keep his promise. This led on to a discussion with her mother about the frustrations father’s death had brought her and how angry she felt about what had happened. Sadly Kathy described how much she missed her father both when at home and at school. ‘There are only two things I want,’ she asserted, ‘my daddy and another balloon.’ (She had recently lost one.)

During these talks, too, Kathy cast light on her ideas regarding the causes of death. Before he had been taken to hospital, she recalled, her father had looked very poorly. He had also looked sad and later she had connected this with his dying: ‘I always felt if you’re very happy you won’t die.’ For this reason she had tried to be happy following father’s death.

In fact there had been many occasions following father’s death when Kathy showed she was afraid someone else in the family might die, especially when there was illness. When Kathy herself was unwell she questioned her mother whether all daddies die, would mother die, would she herself die, adding with much feeling, ‘I don’t want to die because I don’t want to be without you.’

Some months later mother decided to move with the children into a house of their own. This was partly to avoid friction with the grandparents—for example grandmother had become increasingly critical of Kathy especially when Kathy was angry with her mother or was sadly longing for her father—and partly to be more independent. About five years later when Kathy was approaching the age of ten mother remarried and Kathy seemed to accept her stepfather without difficulty. By then things were going well for her: she was proving successful at school, in her relationships and in her various other interests.

Summing up, the therapist writes: ‘Kathy’s initial difficulties with excessive control of feelings and in expressing anger and sadness predated the father’s death but were augmented by it. She brought out some of her own reasons for not wanting to be sad, but her mother’s attitude to expressing and accepting feelings appeared to play a more prominent role. The mother’s recognition of this and her attempts to work with Kathy in this area were very helpful to her, as was the support of the teachers.’

Readers may suspect too, from what we are told of grandmother, that mother’s own difficulty in expressing feeling had originated during her childhood in response to her own mother’s strictures.

These two records speak for themselves; and, when considered in conjunction with other observations of children whose relationships are secure and affectionate, enable us to draw a number of tentative conclusions.

When adults are observant and sympathetic and other conditions are favourable, children barely four years old are found to yearn for a lost parent, to hope and at times to believe that he (or she) may yet return, and to feel sad and angry when it becomes clear that he will never do so. Many children, it is known, insist on retaining an item of clothing or some other possession of the dead parent, and especially value photographs. So far from forgetting, children given encouragement and help have no difficulty in recalling the dead parent and, as they get older, are eager to hear more about him in order to confirm and amplify the picture they have retained, though perhaps reluctant to revise it adversely should they learn unfavourable things about him. Among the seventeen children aged between 3.9 and 14.3 studied by Kliman (1965), overt and prolonged yearning for the lost parent was recorded in ten.

As with an adult who yearns for a lost spouse, the yearning of a child for a lost parent is especially intense and painful whenever life proves more than usually hard. This was described vividly by a teenage girl who a few months earlier had lost her father suddenly from an accident: ‘When I was little I remember how I used to cry for Mummy and Daddy to come, but I always had hope. Now when I want to cry for Daddy I know there isn’t any hope.’

As an initial response to the news of their loss some children weep copiously, others hardly at all. Judging by the Kliman’s findings, there seems a clear tendency for initial weeping to increase with age. In children under five it was little in evidence, in children over ten often prolonged. Reviewing the accounts given by widowed mothers of their children’s initial reactions Marris (1958) is impressed by their extreme variety. There were children who cried hysterically for weeks, others especially some of the younger ones who seemed hardly to react. Others again became withdrawn and unsociable. Furman reports repeated and prolonged sobbing in some children who remained inconsolable, whereas for others tears brought relief. Without far more detailed studies than are yet available, however, we are in no position to evaluate these findings. Not only is it necessary to have records of a reasonable number of children at each age-level but exact particulars are necessary both of the children’s family relationships and also of the circumstances of the death, including what information was given to the child and how the surviving parent responded. Such data are likely to take many years to collect.

As in the case of adults, some bereaved children have on occasion vivid images of their dead parent linked, clearly, with hopes and expectations of their returning. Kliman (1965, p. 87), for example, reports the case of a six-year-old girl who, with her sister two years older, had witnessed her mother’s sudden death from an intracranial haemorrhage. Before getting up in the morning this child frequently had the experience of her mother sitting on her bed talking quietly to her, much as she had when she was alive. Other episodes described in the literature, usually given as examples of children denying the reality of death, may also be explicable in terms of a child having had such an experience. Furman (1974), for example, describes how Bess, aged three and a half, who was thought to have been ‘well aware of the finality of her mother’s death’, announced one evening to her father, ‘Mummy called and said she’d have dinner with us’, evidently believing it to be true.5 On one occasion a male cousin of twenty-two, of whom both grandmother and Wendy were fond, came to call. Without thinking, grandmother exclaimed, ‘Wendy, look who’s here!’ Wendy looked, and then turned pale; instantly grandmother knew what Wendy was thinking.6

Thus the evidence so far available suggests strongly that, when conditions are favourable, the mourning of children no less than of adults is commonly characterized by persisting memories and images of the dead person and by repeated recurrences of yearning and sadness, especially at family reunions and anniversaries or when a current relationship seems to be going wrong.

This conclusion is of great practical importance, especially when a bereaved child is expected to make a new relationship. So far from its being a prerequisite for the success of the new relationship that the memory of the earlier one should fade, the evidence is that the more distinct the two relationships can be kept the better the new one is likely to prosper. This may be testing for any new parent-figure, for the inevitable comparisons may be painful. Yet only when both the surviving parent and/or the new parent-figure are sensitive to the child’s persisting loyalties and to his tendency to resent any change which seems to threaten his past relationship is he likely to accommodate in a stable way to the new faces and the new ways.7

Other features of childhood mourning which have great practical implications are the anxiety and anger which a bereavement habitually brings.

As regards anxiety, it is hardly surprising that a child who has suffered one major loss should fear lest he suffer another. This will make him especially sensitive to any separation from whoever may be mothering him and also to any event or remark that seems to him to point to another loss. As a result he is likely often to be anxious and clinging in situations that appear to an adult to be innocuous, and more prone to seek comfort by resorting to some old familiar toy or blanket than might be expected at the age he is.

Similar considerations apply to anger, for there can be no doubt that some young children who lose a parent are made extremely angry by it. An example from English literature is of Richard Steele, of Spectator fame, who lost his father when he was four and who recalled how he had beaten on the coffin in a blind rage. In similar vein a student teacher described how she had reacted at the age of five when told that her father had been killed in the war. ‘I shouted at God all night. I just couldn’t believe that he had let them kill my father. I loathed him for it.’8 How frequent these outbursts are we have no means of knowing. Often no doubt they go unobserved and unrecorded, especially when the anger aroused is expressed in indirect ways. An example of this is the grumbling resentment shown by Kathy many months after her father’s death which was channelled into her repeated complaints about people who don’t keep their promises. Clearly, had Kathy not had a mother who, guided by the therapist, was attuned to the situation and was able to discover the origin of Kathy’s complaints, it would have been easy to have dismissed the child as inherently unreasonable and possessed simply of a bad temper.

How prone children are spontaneously to blame themselves for a loss is difficult to know. What, however, is certain is that a child makes a ready scapegoat and it is very easy for a distraught widow or widower to lay the blame on him. In some cases, perhaps, a parent does this but once in a sudden brief outburst; in other cases it may be done in a far more systematic and persistent way. In either case it is likely that the child so blamed will take the matter to heart and thereafter be prone to self-reproach and depression.9 Such influences seem likely to be responsible for a large majority of cases in which a bereaved child develops a morbid sense of guilt; they have undoubtedly been given far too little weight in traditional theorizing.

Nevertheless, there are certain circumstances surrounding a parent’s death which can lead rather easily to a child reaching the conclusion that he is himself to blame, at least in part. Examples are when a child who has been suffering from an infectious illness has infected his parent, and when a child has been in a predicament and his parent, attempting rescue, has lost his life. In such cases only open discussion between the child and his surviving parent, or an appropriate substitute, will enable him to see the event and his share in it in a proper perspective.

In earlier chapters (Chapters 2 and 6), I have questioned whether there is good evidence that identification with the lost person plays the key role in healthy mourning that traditional theorizing has given it. Much of the evidence at present explained in these terms can be understood far better, I believe, in terms of a persistent, though perhaps disguised, striving to recover the lost person. Other phenomena hitherto presented as evidence of identification can also be explained in other ways. For example, a bereaved child’s fear that he may also die is found often to be a consequence of his being unclear about the causes of death and as a result supposing that whatever caused his parent’s death might well cause his own too, or that, because his parent died as a young man or woman, the same fate was likely to be his also.

There are, it is true, many cases on record where a child is clearly identifying with a dead parent. Wendy at times treated her father in the same way as her mother had treated him with remarks such as, ‘Anything interesting happen at the office today?’ Other children play at being a teacher, or take great pains over painting, evidently influenced by the fact that the dead father was a teacher or the dead mother a painter. But these examples do little more than show that a child whose parent is dead is no less disposed to emulate him or her than he was before the death. Whereas the examples demonstrate clearly how real and important the relationship with the parent continues to be even after the death, they provide no evidence of substance that after a loss identification plays either a larger part or a more profound one in a child’s life than it does when the parent is alive.

Thus I believe that in regard to identificatory processes, as in so much else, what occurs during childhood mourning is no different in principle to what occurs during the mourning of adults. Furthermore, as we see in Chapter 21, the part played by identification in the disordered mourning of children seems also to be no different in principle to the part it plays in the disordered mourning of adults.

If we are right in our conclusion that young children in their fourth and fifth years mourn in ways very similar to adults, we would confidently expect that older children and adolescents would do so too; and all the evidence available supports that conclusion. Contrary opinions have arisen, I believe, only because the experience of clinicians is so often confined to children whose loss and mourning have taken place in unfavourable circumstances.

Yet there is reason to believe that there are also true differences between the mourning of children and the mourning of adults, and it is time now to consider what they may be.

The course taken by the mourning of adults is, we have seen, deeply influenced by the conditions that obtain at the time of the death and during the months and years after it. During childhood the power of these conditions to influence the course of mourning is probably even greater than it is in adults. We start by considering the effects of these conditions.

In earlier chapters we noted repeatedly how immensely valuable it is for a bereaved adult to have available some person on whom he can lean and who is willing to give him comfort and aid. Here as elsewhere what is important for an adult is even more important for a child. For, whereas most adults have learned that they can survive without the more or less continuous presence of an attachment figure, children have no such experience. For this reason, it is clearly more devastating still for a child than it is for an adult should he find himself alone in a strange world, a situation that can all too easily arise should a child have the misfortune to lose both parents or should his surviving parent decide for some reason that he be cared for elsewhere.

Many differences arise from the fact that a child is even less his own master than is a grown-up. For example, whereas an adult is likely either to be present at the time of a death or else to be given prompt and detailed information about it, in most cases a child is entirely dependent for his information on the decision of his surviving relatives: and he is in no position to institute enquiries as an adult would should he be kept in the dark.

In a similar way, a child is at even greater disadvantage than is an adult should his relatives or other companions prove unsympathetic to his yearning, his sorrow and his anxiety. For, whereas an adult can, if he wishes, seek further for understanding and comfort should his first exchanges prove unhelpful, a child is rarely in a position to do so. Thus some at least of the differences between the mourning of children and the mourning of adults are due to a child’s life being even less within his control than is that of a grown-up.

Other problems arise from a child having even less knowledge and understanding of issues of life and death than has an adult. In consequence he is more apt to make false inferences from the information he receives and also to misunderstand the significance of events he observes and remarks he overhears. Figures of speech in particular are apt to mislead him. As a result it is necessary for the adults caring for a bereaved child to give him even more opportunity to discuss what has happened and its far-reaching implications than it is with an adult. In the great majority of cases in which children are described as having failed totally to respond to news of a parent’s death, it seems more than likely that both the information given and the opportunity to discuss its significance were so inadequate that the child had failed to grasp the nature of what had happened.

Yet not all the differences between childhood and adult mourning are due to circumstances. Some stem from a child’s tendency to live more in the present than does an adult and from the relative difficulty a young child has in recalling past events. Few people grieve continuously. Even an adult whose mourning is progressing healthily forgets his grief briefly when some more immediate interest catches hold of him. For a child such occasions are likely to be more frequent than for an adult, and the periods during which he is consciously occupied with his loss to be correspondingly more transient. As a result his moods are more changeable and more easily misunderstood. Furthermore, because of these same characteristics, a young child is readily distracted, at least for the moment, which makes it easy for those caring for him to deceive themselves that he is not missing his parents.

If this analysis of the differences in the circumstances and psychology of a bereaved child and of a bereaved adult is well based, it is not difficult to see how the idea has developed that a child’s ego is too weak to sustain the pain of mourning.

It is inevitable that when one parent dies the survivor’s treatment of the children should change. Not only is the survivor likely to be in a distressed and emotional state but he or she now has sole responsibility for the children instead of sharing it, and now has to fill two roles, which in most families have been clearly differentiated, instead of the single familiar one.

The death of a child’s parent is always untimely and often sudden. Not only is he or she likely to be young or in early middle-age, but the cause is much more likely to be an accident or suicide than in later life.10 Sudden illness also is not uncommon. Thus for all the survivors, whether of the child’s, the parent’s or the grandparent’s generation, the death is likely to come as a shock and to shatter every plan and every hope of the future. As a result just when a child needs most the patience and understanding of the adults around him those adults are likely to be least fit to give it him.

Already in Chapter 10 we have considered some of the problems facing widows and widowers with young children and the limited and often very unsatisfactory arrangements from among which they have to choose, one of which is to send the children elsewhere. Here we are concerned only with the behaviour of the surviving parent when he or she continues to care for the children at home. Since the behaviour of widows and of widowers towards their children is likely to differ, and in any case we know much more about that of widows, it is useful to consider the two situations separately.

A widow caring for her children is likely to be both sad and anxious. Preoccupied with her sorrows and the practical problems confronting her, it is far from easy for her to give the children as much time as she gave them formerly and all too easy for her to become impatient and angry when they claim attention and become whiny when they do not get it. A marked tendency to feel angry with their children was reported by about one in five of the widows interviewed by Glick and his colleagues (1974). Becker and Margolin (1967) describe the mother of two small girls, of three and six, who could not bear the older one’s whining and frequently hit her for it.

An opposite kind of reaction, which is also common, is for a widowed mother to seek comfort for herself from the children. In the Kliman (1965) study no less than seven of the eighteen children ‘began an unprecedented custom of frequently sharing a bed with the surviving parent. This usually began quickly after the death and tended to persist’ (p. 78). It is also easy for a lonely widow to burden an older child or adolescent with confidences and responsibilities which it is not easy for him to bear. In other cases she may require a child, usually a younger one, to become a replica either of his dead father or else, if an older child has died, of the dead child see (Chapter 9). Constant anxiety about the children’s health and visits to the doctor as much to obtain his support as for the children’s treatment occur commonly.

Not only is a widowed mother liable to be anxious about the children’s health but she is likely also to worry about her own, with special reference to what would happen to the children were she to get ill or die too. Sometimes, as Glick et al. (1974) report, a mother will express such anxieties aloud and within earshot of the children. In the light of these findings it is not difficult to see why some bereaved children are apprehensive, refuse to attend school and become diagnosed as ‘school phobic’ (see Volume II Chapter 18).

Anxious and emotionally labile herself and without the moderating influence of a second opinion, a widow’s modes of discipline are likely to be either over-strict or over-lax, and rather frequently to swing from one extreme to the other. Problems with their children were reported as being of major concern by half of the widows with children who were studied by Glick in Boston.

Our knowledge of changes in the behaviour of widowed fathers towards their bereaved children is extremely scanty. No doubt those of them who care for the children mainly themselves are prone to changes in behaviour similar to those of widows. Especially when the children are female and/or adolescent are widowed fathers apt to make excessive demands on them for company and comfort.

Should the children be young, however, their care is likely to be principally in other hands, in which case a widowed father may see much less of them than formerly. As a result he may well be unaware of how they feel or what their problems are. Bedell (1973)11 for example, enquired of 34 widowers how they thought their children had been since they lost their mother and what changes they had noticed in them. Few of the fathers had noticed any changes and even then only small ones. In the light of what we know about children’s responses to loss of mother, these replies strongly suggest that the fathers were out of touch and poorly informed.

From this brief review we conclude that a substantial proportion of the special difficulties which children experience after loss of a parent are a direct result of the effect that the loss has had on the surviving parent’s behaviour towards them. Nevertheless there are, fortunately, many other surviving parents who, despite their burdens, are able to maintain relationships with their children intact and to help them mourn the dead parent in such a way that they come through undamaged. That others fail, however, can hardly surprise us.

1 On receiving a portrait of his mother who had died when he was nearly six.

2 The case of Wendy is a shortened version of an account given in a paper by Barnes (1964). The case of Kathy is a shortened version of an account, also given by Barnes, in the book by Furman (1974, pp. 154–62).

3 In view of mother’s uncertain health it seems more likely that the principal source of Wendy’s fear lay in clues she had picked up from father or grandmother, or mother herself, that they were anxious about mother’s condition (see Volume II, Chapter 18).

4 It seems likely that father’s open favouritism of Kathy may have accounted for some of Ted’s problems (J.B.).

5 Fortunately Bess’s father knew how to respond. Gently he replied, ‘When we miss Mummy so very much we’d like to think that she is not really dead. I guess it will be a sad dinner for both of us’ (pp. 24–5).

6 Wendy’s misinterpretation, born of hopes and expectations, has an almost exact parallel in the experience of a middle-aged widow whose husband had died suddenly of a heart attack in the street. Seven months after his death, a police constable came to her flat and informed her that her husband had had a minor accident and had been taken to hospital. At once she thought to herself how right she had been all the time in thinking that her husband was still alive and that she had only been dreaming that he was dead. A moment later, however, as her doubts grew, she enquired of the constable whom he was looking for; it proved to be her neighbour next door.

7 These practical problems are well discussed by Furman (1974, pp. 26 and 68).

8 This example, as well as the reference to Richard Steele, is taken from Mitchell (1966).

9 Examples are given in Chapters 21 and 22. See also the case of a woman suffering from a phobia of dogs reported by Moss (1960) and described at the end of Chapter 18 in Volume II.

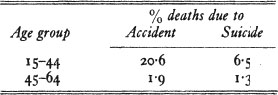

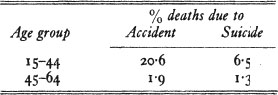

10 In the U.K. the proportion of deaths due to accident or suicide in the younger age-groups is many times greater than it is in older ones. The table below gives the percentages for men and women who died before they had reached 45 years and for those aged between 45 and 64, for the year 1973.

Figures are derived from the Registrar-General’s Statistical Review of England and Wales for 1973 (H.M.S.O. 1975).

11 Quoted by Raphael (1973).