Some of the factors contributing to weight loss through better sleep—having more energy for exercising, having less need for the sugary, temporarily energy-boosting snacks that lead to weight gain—are rather obvious and quite easy to understand. But the connection between sleep and weight goes far beyond these simple connections. The latest science shows that our metabolic rate appears to change based not only on our age, gender, and medical issues, but also on how well (or how poorly) we sleep. The physiological functions that influence eating, energy balance, and metabolism are strongly tied to circadian rhythms (see page 29) and sleep. In other words, disrupting your biological clock can have important metabolic consequences that affect your weight for months or years to come.1 Even in very lean individuals, experiments have shown that short-term sleep restriction affects glucose tolerance and Cortisol and growth hormone secretion.2

It’s been well established that obesity is on the rise in the United States, but it’s not solely because of dietary habits, genetics, and less physical activity. There seem to be environmental, social, and behavioral influences that promote overeating and inactivity. Ironically, these same factors also influence your sleep.

One of the markers for body fat that’s used by many doctors today is a calculation using your weight and height that measures what’s called the body mass index (BMI). Under this system, an adult who has a BMI of between 25 and 29.9 is considered overweight; an adult with a BMI of 30 or higher is considered obese. To calculate your own BMI, go to www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi [inactive].

While the BMI is used by many health care practitioners to determine if patients are overweight or obese, it can be misleading in some adults, especially men and women who have large frames or an abundance of muscle. Even though these men and women may have BMIs of higher than 25, they might not have excessive body fat. Talk to your doctor about your weight to see if you are at risk for obesity.

As we saw in the chart on page 11, the rise in obesity parallels with uncanny accuracy a corresponding decrease in sleep hours over the very same time frame. It’s quite disturbing to me to see the correspondence between the obesity rate of more than 35 percent of adults in the United States and the least sleep time per night in history of 6.5 hours.

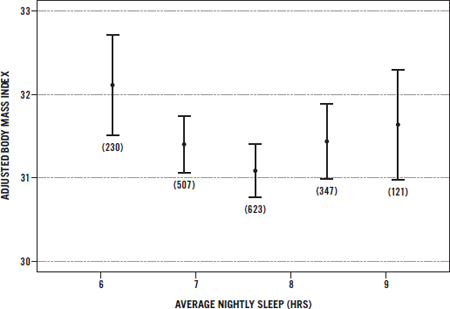

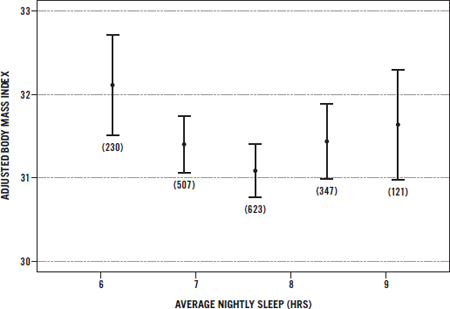

Of course, there are other factors at play, including sedentary lifestyles, genetics, and chronic overeating. Still, groundbreaking research continues to link sleeping less with being overweight or obese. In fact, epidemiologic studies from Spain, Japan, and the United States show an interesting relationship between BMI and sleep in women. Women who had the lowest, healthiest BMIs (20 to 25) spent on average 7.7 hours in bed per night.3 In addition, a few studies link too much sleep to overweight or obesity.

Right now, we know several reasons why sleep loss results in added weight—possibly even obesity.

To understand why changes in glucose metabolism occur, we have to go back to basic physiology. Your body is constantly trying to balance out the glucose in your system. Remember, glucose (a simple sugar) is one of the basic building blocks of every food that you eat. Your body breaks down food into glucose to use as energy. Having too much glucose in your system, a condition called hyperglycemia (high blood sugar), is a major problem for people with diabetes, and it can have big consequences for your health. Symptoms of hyperglycemia include frequent urination, increased thirst, and high levels of sugar in the urine. When you have too little glucose in your system, a condition called hypoglycemia or low blood sugar, you have symptoms such as dizziness, shakiness, sweating, hunger, headache, paleness, sudden moodiness for no apparent reason, clumsiness, seizure, and inattentiveness.7

“Homeostasis,” or balance, is achieved when the liver produces glucose from food and then the tissues of your body use the right amount of it. Your muscles and fat use the glucose with the help of insulin secreted by the pancreas. Organs such as the brain use the glucose without the help of insulin.

Sleep loss also affects the ability to process foods such as carbohydrates, which ultimately leads to increased blood glucose (blood sugar). As your blood sugar level rises, your pancreas overproduces insulin. This results in the storage of excess body fat and possible development of type 2 diabetes, which is defined as a chronically elevated level of glucose in the blood. Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes, affecting 90 to 95 percent of the 24 million people with diabetes in the United States today.8 Another 57 million Americans over age 20 are considered prediabetic, having blood glucose levels that are chronically higher than normal, but not as high as those in people with diabetes.

The balance of glucose production and use changes throughout the day and night as one of your circadian rhythms. Your body’s glucose utilization rate is higher in the morning than in the evening. In the first half of the night, you use glucose more slowly because your body doesn’t require as much of it during deep sleep (Stages 3 and 4), when it rests and heals.

However, glucose metabolism starts to increase in the second half of the night when you enter REM sleep. And amazingly, the better you sleep, the more calories you burn. The longer you sleep, the more REM sleep you get, so you will burn more calories if you sleep longer.9 However, as we have seen with the BMI index, there is a happy medium. Those who sleep too long have slower metabolisms because they stay in bed instead of expending energy!

When your body is even slightly sleep deprived, three things happen. First, you hold on to glucose longer. Sleep deprivation also causes your body to use this glucose less efficiently. Finally, when you are sleep deprived, your body’s ability to create insulin quickly when you eat food is reduced. In summary, if your body is even partially sleep deprived, the food you eat is not burned by your metabolism as quickly or efficiently. The result? The food is stored as fat!

I like to think of hormones as messengers connecting various systems and command centers of the body; they get produced in one part of the body by tissues and glands such as the thyroid, adrenals, and pituitary and then pass into the bloodstream for delivery to distant organs and tissues, where they act to modify structures and functions.

Did you know that your appetite is regulated by signals your hormones send to your brain? There is a specific place in the brain—the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus—that controls the on/off switch for appetite. This tiny part of the brain also controls body temperature, thirst, fatigue, and most circadian rhythms.

Hormones act like traffic signs and signals by telling your body what to do and when and making sure its machinery runs smoothly and maintains homeostasis, or balance. Hormones are used by all organ systems, and their proper balance relies on sleep. Much of how you feel—tired, ravenous, full, excited, thirsty, hot, cold, stressed out—is related to the secretion of hormones and their impacts on your mind and body. There are many hormones that are affected by sleep and that, in turn, affect weight, but the basic ones involved are leptin, ghrelin, cortisol, and growth hormone.

Two hormones, ghrelin and leptin, hold the remote control for your appetite. Ghrelin is the green light that says, “Go get some food!” Leptin is the red light that says, “Stop eating now!”

Ghrelin is secreted by your stomach when it’s empty, increasing your appetite. It sends a message to your brain that says, “I’m hungry. Feed me.”

When your stomach is full, leptin, which is secreted by fat cells, sends a message to your brain that says, “Stop eating. I’m done.” This appetite hormone regulates food intake, energy expenditure, and body weight. Leptin decreases appetite by causing you to feel full and increases energy output by telling you that you have fuel you can burn. Scientists believe that people who are obese may have a problem with the receptors for leptin in their brains, so their appetites do not respond when this hormone says, “Stop eating now.” In some cases, they even may be getting the opposite message—”Keep eating”—from leptin. But how do these two appetite hormones relate to sleep?

Poor sleep lowers the level of leptin (the “stop” hormone) and boosts the production of ghrelin (the “go” hormone), resulting in your feeling hungrier. One key study at the University of Chicago showed that when healthy men were allowed just 4 hours of sleep a night for 2 nights, they averaged an 18 percent drop in leptin and a 28 percent increase in ghrelin.10 These sleep-deprived participants perceived an average 24 percent increase in their hunger and a 23 percent increase in their appetite—particularly for high-calorie and high-carb foods. “Hunger”—the sensation that precedes eating—is the feeling of wanting to eat, and “appetite” is the physical need to eat until full. When your brain doesn’t get the message that you are full, you keep eating and eating . . . and eating.

With normal sleep, there are small initial rises in leptin and ghrelin at night. During the second half of the night, ghrelin decreases. However, comprehensive research shows that partial sleep deprivation (sleeping less than about 6.5 hours) causes the level of leptin to be lower and the level of ghrelin to be higher during the day—even when the body should be sending signals to say that it has had enough food.11

The study showed that total sleep time was negatively correlated with the circulating level of ghrelin. Therefore, the less sleep a person got, the more ghrelin he or she produced. The accuracy of the brain’s assessment of whether it needs more energy (food) is questionable when a person is sleep deprived.12

Thus, when you are sleep deprived, a signal may be sent to your brain to ask for more food even when your stomach is full!

Another chemical that can increase your appetite is cortisol, a naturally occurring hormone that helps to regulate glucose. This hormone causes your body to break down muscles for energy and store excess calories as fat. And, as you might have guessed, you want to control your level of cortisol if you are trying to lose weight.

Problem is, you can’t control your level of Cortisol without getting enough sleep. Lack of sleep increases cortisol production, making you store fat and burn muscle. A high cortisol level also increases your appetite! In other words, poor sleep does the exact opposite of what you are trying to accomplish. Not surprisingly, your cortisol level is highest early in the morning while you are still sleeping and during periods of high stress, and lowest in the early stages of deep sleep. Some fat-burning supplements allege that they can combat the effects of cortisol. But a good night’s sleep is the far better, more effective remedy. As you’ll learn later in this book, diet supplements that contain stimulants can hinder sound sleep and ultimately work against your weight-loss goals.

Cortisol is produced by the adrenal glands, the primary mission of which is to produce a hormone that converts stored energy into usable energy. When you find yourself in a threatening situation, the brain activates these glands to release cortisol, which literally puts energy in your personal fuel tank in the form of blood glucose.

When you have an acute emergency or one that lasts for a short time—a few hours, perhaps even a couple of days—usually no permanent physical damage is done. Your heart rate and blood pressure increase, and the alarm neurotransmitter, adrenaline (which is also produced by the adrenal glands), floods your body, making your heart beat faster and increasing the bloodflow to your muscles and intestines.

When stress is present for days or weeks, it is called chronic stress. In response to it, the adrenal glands keep pouring out cortisol, and problems arise. The elevated cortisol level makes you burn up your body’s readily available resource (glucose in the blood) for energy until there is no more available. Then, instead of drawing upon stored energy (fat), your body begins to break down muscle and other tissues to keep going. So a high cortisol level leads to the breakdown of muscle and other tissues—but not of fat. In addition, long-term cortisol overproduction because of chronic stress inhibits sleep, which increases your appetite. Remember that during sleep is when your primary neurotransmitters get replenished. Without this replenishment, you feel fatigued, achy, and depressed.

Another problem with chronic stress is that cortisol increases the desire for carbohydrates by increasing the production of neuropeptide Y, a neurotransmitter found in the brain. Sarah Leibowitz, PhD, of Rockefeller University, found that neuropeptide Y stimulates eating, particularly of carbohydrates. Neuropeptide Y has its greatest effect on appetite early in the day, after the overnight fast, and its level is increased after any period of deprivation—including dieting.13

So, it is not surprising that dieters and people under stress reach for high-carbohydrate foods that pack on the pounds, such as breads, sweets, pasta, and cereals.

If you do not have a healthy way of coping with chronic stress, your constant exposure to stress hormones will eventually cause your body to become overloaded. When you’re stressed out for a long period of time, it can result in a dramatic decline in both your physical and mental health and a possible incline in your weight.

When cortisol levels remain high from chronic stress and sleep loss, the associated accumulation of abdominal fat (also called belly fat and visceral fat) expands the waistline and results in an apple-shaped body.14 We’re now learning that people with apple-shaped bodies have an increased blood level of a proinflammatory marker called C-reactive protein that indicates that they’re at greater risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Some findings indicate that greater girth is more closely associated with inflammation than obesity concentrated in other parts of the body.15

C-reactive protein is produced by the liver only during episodes of acute inflammation. It is highly correlated with obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancers. The good news is that weight loss is associated with a significant decrease in proinflammatory markers like C-reactive protein, as well as decreases in LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and triglyceride levels, blood pressure, and fasting blood glucose level.16

During our younger years, when cortisol secretion is stimulated by stress, a feedback mechanism based in the hypothalamus shuts the cortisol off. As we get older, however, this feedback loop does not work so well, and our ability to manage the stress response is compromised. Stress interferes with weight loss and disrupts normal sleep by interfering with the sleep cycle.

Losing sleep also boosts the secretion of cortisol, making us feel hungrier and have unnecessary cravings.

Studies show that stress and the associated sleep loss do two things to affect your weight.17

STRESS AND SLEEP HORMONES

| HORMONE | WHAT IT’S SUPPOSED TO DO | WHAT IT DOES WHEN YOU’RE STRESSED | WHAT IT DOES WHEN YOU’RE SLEEP DEPRIVED |

| CORTISOL (THE STRESS HORMONE) | Increases your blood sugar; helps you metabolize fat, protein, and carbohydrates; suppresses your immune system | Increases its blood level to give you energy; increases your appetite; over time, damages your body | Increases your appetite; decreases your immune function |

| SEROTONIN (A NEUROTRANSMITTER) | Helps transmit messages along your nerve pathways | Becomes depleted, causing burnout | Makes you want to eat simple sugars |

| GHRELIN (THE “GO” HORMONE) | Tells you to eat more | Increases its production | Increases your appetite |

| LEPTIN (THE “STOP” HORMONE) |

Tells you to stop eating | Decreases its production | Makes you feel less full than you really are |

| INSULIN | Helps regulate your blood sugar level | Decreases its production | Increases your fat stores |

Poor sleep also deprives the body of adequate growth hormone (GH). GH is a powerful antiobesity hormone that decreases the rate at which your cells utilize carbohydrates and increases the rate at which they use fats (all good for weight loss!). We now know that as deep-sleep time decreases, so does the secretion of GH. In addition, by the time a person is 35, GH production can have decreased by as much as 75 percent due to aging. And sleep deprivation could make this worse.

As soon as you hit deep sleep, about 20 to 30 minutes after you first close your eyes and then again during each sleep cycle, your pituitary gland starts to release high levels of GH—the most it will secrete at any point in the day. Without that sleep, your level of GH is significantly reduced, negatively affecting your proportion of fat to muscle. Over time, a chronically low GH level is associated with more fat and less lean muscle.

If you’re finding it hard to keep these hormones—leptin, ghrelin, cortisol, and growth hormone—straight, don’t worry; the chart below will guide you.

| HORMONE | WHAT SLEEP LOSS DOES TO IT |

| LEPTIN | Reduces it, so you eat more because there is nothing telling you to “stop” |

| GHRELIN | Increases it, so you eat more because it says “go” |

| CORTISOL | Increases it, so you eat more |

| GROWTH HORMONE | Reduces it, so you store more glucose as fat |

When you are sleep deprived, do you find that you snack more? Several recent studies have shown that people who are sleep deprived seek extra calories in the form of snack foods. In one study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition,18 researchers found that when volunteers had slept only 5.5 hours, they ate their normal amounts at mealtimes, but their snack intake increased dramatically. On average, these people ate about 1,000 calories in snacks (65 percent of them carbohydrates), all of it between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m.!

The amount of energy the body uses over a given time period is called its energy expenditure, and it is the sum of several different components.

Currently, there’s not enough research to conclusively link weight gain with the decrease in energy expenditure that is related to sleep loss. But there are some interesting signs that point in that direction.

Thus, the research suggests that sleep loss results in decreased physical activity and in weight gain. Still, we cannot say for sure that there are not other factors influencing energy expenditure.

Ultimately it seems likely, as well as logical, that your body’s ability to use glucose and your hormones’ effects on your appetite and fat storage are related to both sleep loss and weight gain.

Sleep loss, in a sense, disconnects your brain from your stomach. With sleep loss, eating becomes an unconscious act, and you also have a hard time controlling what you eat. The Chicago study mentioned earlier in this chapter found that the volunteers’ appetites for caloriedense, high-carbohydrate foods like sweets, salty snacks, and starchy foods increased by 33 to 45 percent when they slept only 4 hours a night. This translates into two strikes against you when you get too little sleep.

Other studies have found that in people of normal weight, leptin decreases the perception of a sweet taste, making sweet foods less appealing. Reduced leptin makes people who are overweight and obese continue to taste the sweetness. Since loss of sleep causes the body to produce less leptin, if you are overweight and sleep deprived, your appetite will seem to never be satisfied, and everything you stuff in your mouth will taste great!

All of these findings point to the same conclusion: Sleep loss results in weight gain. Even though the sleep/obesity link is complicated, its existence is substantiated by the latest scientific studies, and the medical community is beginning to recognize the critical role proper sleep plays in weight regulation.

But there is much more. The unique aspects of being a woman have a dramatic effect on your ability to get good-quality sleep. In the next chapter, I will tell you how your menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause are guaranteed sleep disrupters, and I’ll give you some sleep tips to use during these times.