October 2014,

with a Hanford excursion in August 2015

THE RED ZONES

1: Over Ten Times the Level Measured the Previous Week

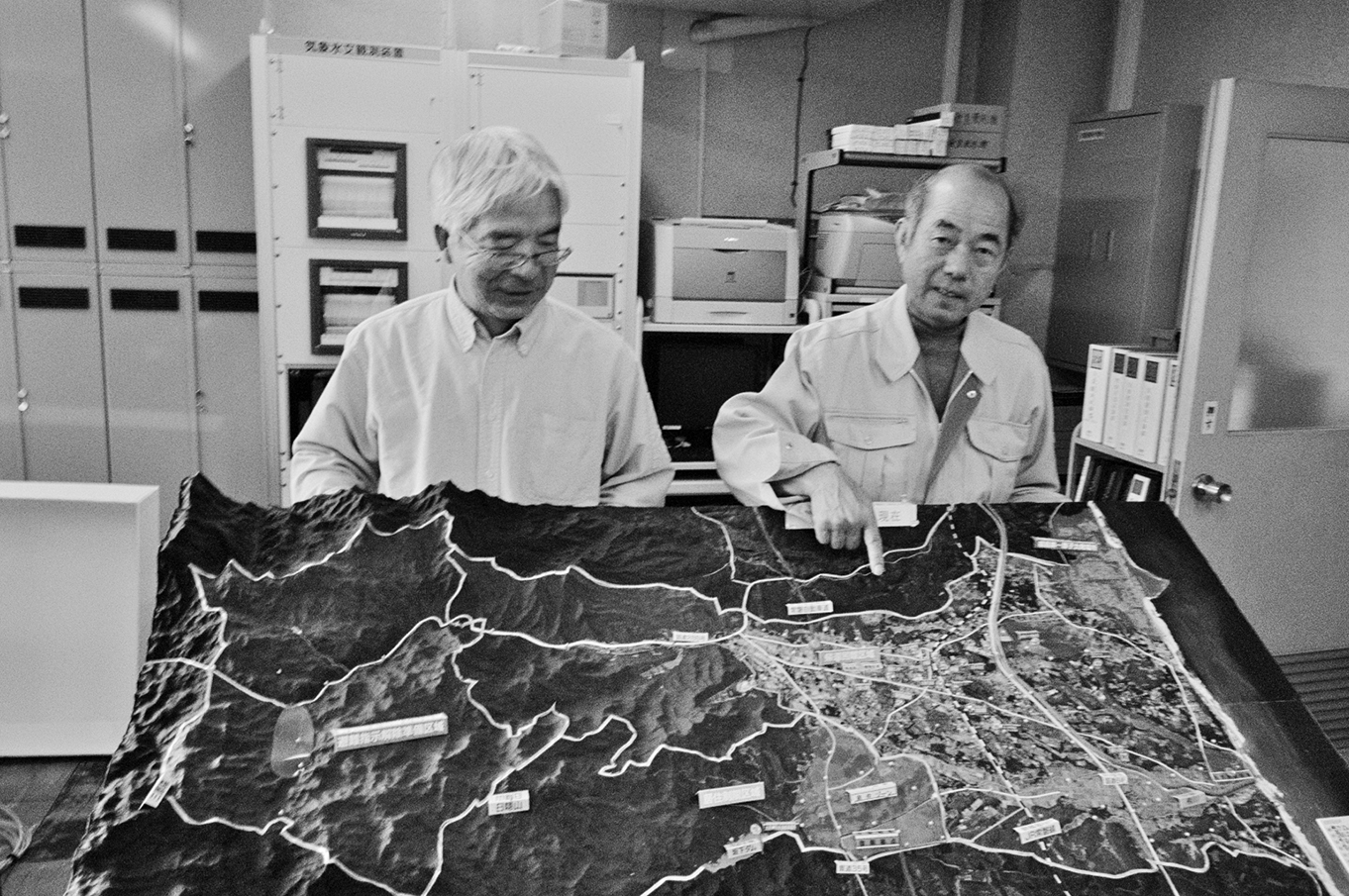

First those faraway Americans had forgotten about the accident*—after all, its fallout barely showed up in Oregon milk—and presently most residents of Tokyo (excepting steadfast Friday night protesters and a few tired self-educated Cassandras such as Mr. Yamasaki, whose NGO had tested my Iwaki tomatoes) took heart again, because Reactor Plant No. 1 had matured from a national calamity into the merest affliction of distant country cousins—three cheers for the wall of ice!—while in Iwaki people diligently defended themselves against harmful rumors by eating whatever was set before them, even as the decontaminators improved everything into neat islands of black bags—and by the time of my third visit to the disaster zone, when I managed at last, thanks to months of effort on the interpreter’s part, to penetrate legally or quasi-legally well into the exclusion zones—yes, I even got to see and photograph Plant No. 1 from a convenient radioactive overlook!—it turned out that the people who guided me, which is to say those with knowledge and local experience—a district head, municipal employees, a former reactor worker who had been on duty at Plant No. 2 on and after March 11, 2011; and I should also mention the various taxi drivers and rental car personnel daily or almost daily associated with travel through the red zones—had become as blasé as the rest of us. At the Iwaki gas station where an old man and a young boy were cleaning our hired vehicle, which had just returned from Tomioka, Okuma and Namie, I asked the former reactor worker to warn them that they were scrubbing away fallout, which must be particularly spicy around the wheel wells—to which the old man courteously replied: “Never mind.”—He and the boy went on scrubbing.—All hail! At last (and so it must be for you who live in my future) radiation contamination had been normalized.*

It was invisible, you see. There was no immediate danger. They’d done it for the nation. One had to fight harmful rumors.

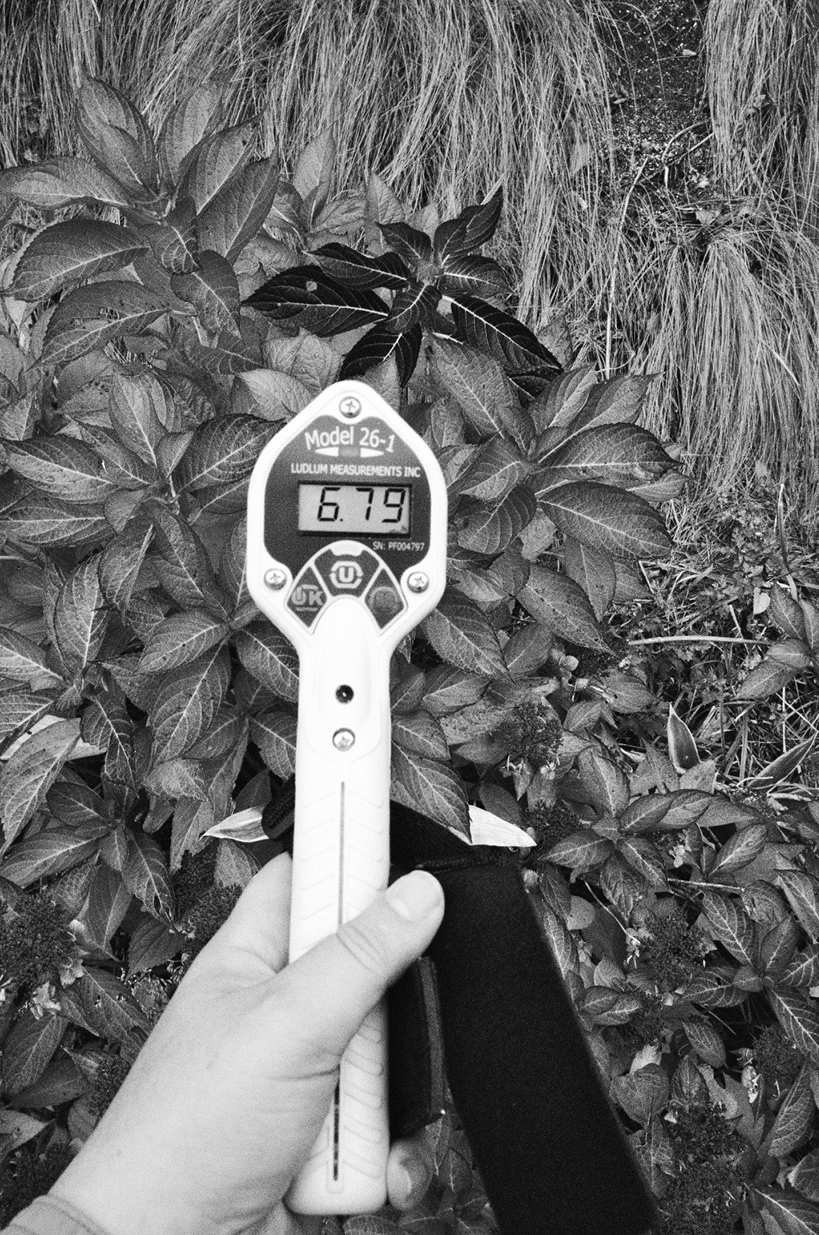

As for me, I felt the opposite, because at last I possessed an adequate toolkit, and measuring the real-time scintillations of the objects around me in those red zones proved unnerving.

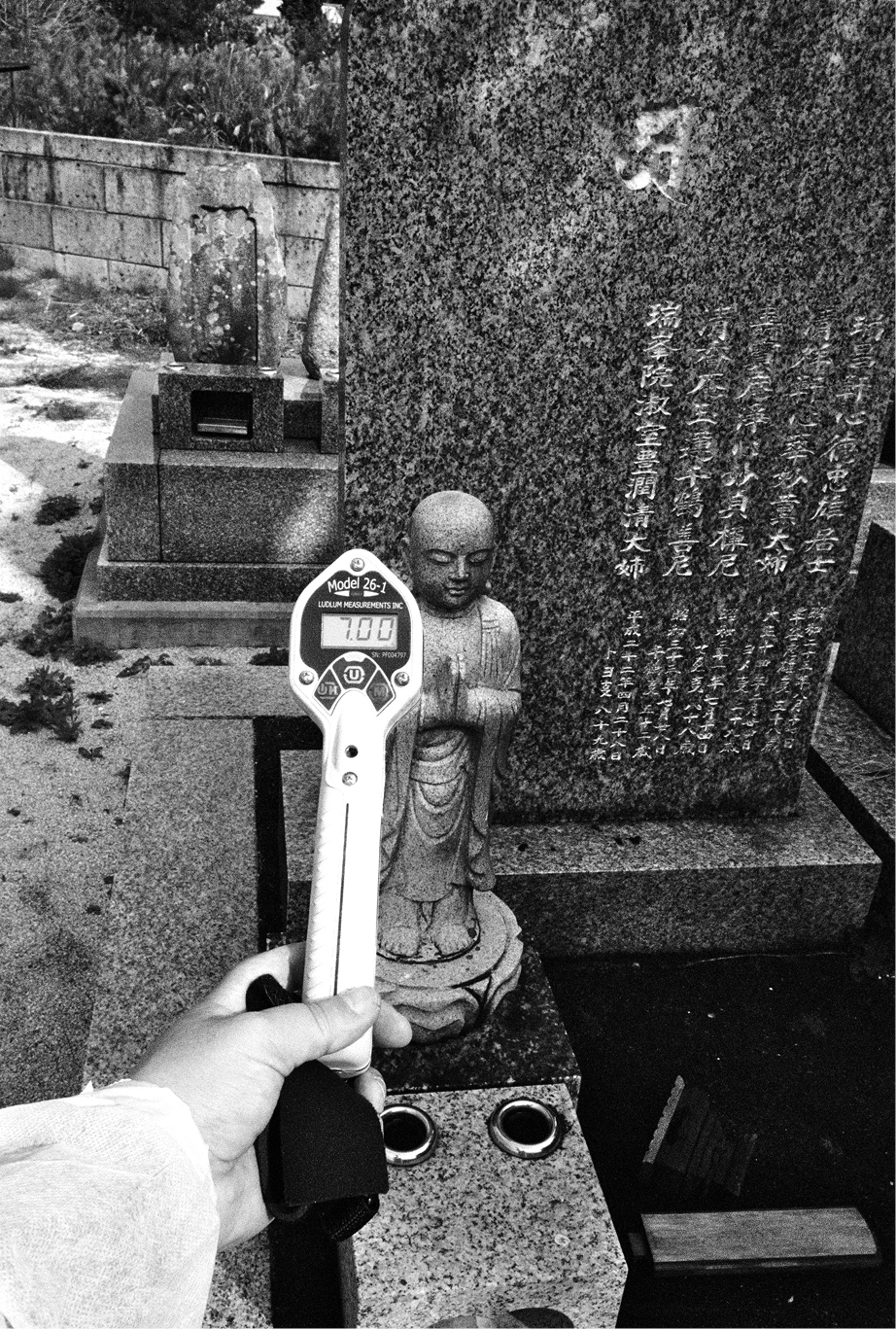

THE PANCAKE FRISKER

Because the dosimeter (as I have so often complained) could only show accrued gamma radiation, not alpha or beta, and because it could not reveal hot spots with sufficient timeliness to prevent them from quite possibly hurting me, I decided to call Clyde up in Richland, Washington. He told me that what I required was a pancake frisker. It looked like a little yellow golf club, he said. He took his everywhere; it seemed to be a pretty swell machine. Scrap metal dealers appreciated it because it enabled them to weed out the odd radioactive nightmare in a pile of junk—an increasingly frequent situation, Clyde confided, at which point he and I shared a millisecond of telephone silence, to mark the eternal wickedness of this world. Extolling the device’s sensitivity, Clyde now entertained me with the truckload of anecdotal hay that had alarmed some ingenuous soul who imagined himself into an emergency; one needed to remember, Clyde said, that alfalfa fertilizer, like bananas, contained a naturally occurring radioisotope of potassium.—By now I liked him considerably. He was as cheerful as a cricket. He even offered to loan me his very own frisker, but only if the results stayed off the record, since he had been too busy to recalibrate it. I replied that I might as well just buy one. The price was $750. Clyde gave me the direct number of the main office in Sweetwater, Texas. I fretted aloud that some other salesman would deprive him of his commission, which he had certainly earned with his amusing stories, but he said, “Don’t worry; they take real good care of me.”

First things first: The Sweetwater people warned that their product was subject to export license regulations, so I wrote a note to whomever it might concern that if I happened to carry my new toy outside the United States, I would exert every muscle to bring it home. That was good enough, they said, and which two units did I wish the display to read in? Out of loyalty to the dosimeter, I chose microsieverts; the other unit might as well be cpms, which the Tepco friskers had employed at Tomioka. So I placed my order, hoping that the pancake frisker could fulfill at least some of Clyde’s claims. The company was busy; orders got backlogged (another omen that radioactivity would scintillate ever more brightly in our collective future); but a week sooner than they had promised, I received my Model 26-1, which was truly yellow, and did look sort of like a golf club. Eli in the technical support department advised me to slowly sweep it back and forth when I was in the field. I asked how well it could measure food.—“It should be very helpful, I would think,” he said. He was an au courant and tolerant fellow, whom I ended up calling several times. He said that gamma rays should definitely register in any meal; as for beta, at least one of Fukushima’s two common cesium isotopes would announce itself in a friskable sort of way. The iodine-131 might or might not be revealed; I consoled myself that hardly any of that should remain in the red zones, for it had been an immediate product of the accident, and its 10 half-lives occupied only 80 days. As for Nuclear Plant No. 1’s continuous flow of ocean-bound tritium, those emitted beta particles were minuscule and might not be friskable. To measure their concentrations I would need, among other apparatus, a cart to carry my own private tank of radioactive potassium-10 gas. Beset by a peculiar feeling that my nation’s guardians of airport safety might not look favorably upon such luggage, whether I checked it in the hold of the plane or brought it on board to stow in the overhead bin, I gave up on monitoring tritium. Who could say whether I would even reach the ocean? (As a matter of fact I did, in Okuma. According to the pancake frisker, the air dose there was astonishingly low. But I abstained from chasing waves.) What then about a river or a glass of water? Remembering what that lying salesman named Ray had promised me when I bought the dosimeter, I now inquired, with more curiosity than hope, whether I could simply sweep the frisker over either of those. Sadly, Eli explained that the hydrogen atoms with which water is afflicted tend to mask neutrons. But I hereby testify most heartily that the thing did everything that Eli and Clyde said it would. In Japan its readings correlated extremely well with those of municipal and prefectural officials; moreover, it was, as I’d hoped the dosimeter would be, fun. I immediately fascinated myself by measuring the radioactivity of my daughter’s cat (0.12 microsieverts per hour, which was twice as high as my darkroom coating table and exactly the same as my kitchen counter). My neighbors in Sacramento took pleasure in the frisker at first, although the low and stable levels around there rapidly bored them; you in the future doubtless enjoy more interesting readings.

The pancake frisker was about 13 inches long from the top of its rubberized handle (which concealed two AA batteries) up to the forward point of its hexagonal head. Three buttons decorated it. When I pressed the leftmost one, the machine uttered a three-tone chirp not unlike the sound one of my sweetest girlfriends used to make when she climaxed. Then its screen lit up, and in NORMAL mode the frisker began to express the moment-by-moment scintillations of, say, the dining room table of an apartment in San Francisco: 46, 30, 35, 40, 26, 19, 27, 34, 22 counts per minute—and with each new figure the thing stridulated adorably. Anytime I wished, I could push the middle button, to toggle the units into microsieverts per hour, and from that dining room table I now present several of those: 0.022, 0.118, 0.50, 0.32, 0.20, 0.102, 0.122 and 0.118. These altered with such rapidity that in the red zones, where I was always in a hurry, I sometimes scribbled down only the first digit or two of each item in this ever altering series.

My friend Jay loved the pancake frisker, and said: “It’s like having another sense!” This comment was on the money, for I can and will tell you what such places as Tomioka, Okuma or Iitate looked like to me, and observations of abandoned decrepitude do convey something useful, but what about an innocent-looking thicket or meadow? Please recall Ed Lyman’s aphorism: “The issue is how uniform are the hot spots?” Without a scintillation counter I could not have addressed that issue.*

In sum, the best way for me to complete my word-pictures of the red zones is to overlay my descriptions with numbers: Here is how that meadow appeared . . . and in that meadow a plume of pampas grass was emitting so many nasty microsieverts.

I ask your pardon if I now devote a further couple of paragraphs to the frisker’s modes of measurement, and to how I interpreted them. Since these numbers are of extreme importance in my accounts of the red zones, I owe it to you to say where they came from. For any reader who is repulsed by arithmetic (and also for me, because the results bemused me), there is that basic comparative chart back here, so that rather than wearying yourself with converting from counts per second to microsieverts per year, you can simply look up an interesting shrine torus or sidewalk-stretch and see how many tens or hundreds of times more radioactive it was than my kitchen counter in Sacramento.

So. NORMAL produced a string of numbers. Well, in practical terms, how “hot” was that dining room table in San Francisco? Whenever I cared, I could push the frisker’s righthand button. On my first click, the device would go into MAX mode. The display then showed only the highest reading. If the emitter were stable, the local maximum generally ceased to alter within 30 seconds. Here in this dining room the radiation usually got up to around 0.2 micros per hour, or, if you prefer to toggle into other units, 65 cpms. This proved convenient and useful in its way: Whenever officials of the Transportation Security Administration, a well-meaning but arrogant institution that sometimes bullied American air travellers back in the days when I was alive (their agents specialized in slicing the linings of my various suitcases), refused to tell me how powerful their X-ray was, all I had to do was forget to shut off my pancake frisker, which accidentally happened to be in MAX mode as it rode down their conveyor belt.* That told me just what I wished to know, and if you are curious you can look it up in that same comparative chart.

A second push of the rightmost button, and then a touch of the lefthand button, and the frisker entered what came to be my favorite mode, SCALER, which averaged all scintillations over the course of a minute: The dining table was 30 counts per minute, or 0.002 micros per minute. That worked out to 0.12 micros an hour—the same as my daughter’s cat, and indeed my average reading for San Francisco. In actual fact, this was two and a half times higher than Tokyo’s Shinjuku district had been on the day before the nuclear accident. In 2014, San Francisco and Tokyo were (by the frisker’s measurement) nearly equally radioactive, which is to say well below normal background for many parts of the world.

Multiplying this innocuous number by 24 gives 2.88 micros per day. You may recall that in San Francisco and Tokyo the dosimeter usually turned over a single microsievert* in 24 hours. To have one device reading nearly three times more radiation than the other concerned me, and I spent some time considering it, because once I reentered the hot zone, my health would depend on the accuracy of my measurements. Calling the ever patient Eli, I told him about the granite countertop in the bathroom of my hotel suite in Charleston, West Virginia. I had measured it 10 times for one minute each in the SCALER mode. Usually the display read 0.005 or 0.006 micros per minute, but once it showed 0.004 and once it came back 0.007—a considerable variation, I thought.

“Well,” said Eli, “there’s bounce and sway on the needle, especially in the low values. Make sure you let that thing run on NORMAL in that energy field and let it settle.”

I had done this in Charleston. So I asked: “Is it less accurate in a low-radiation environment?”

“The hotter the field is, the easier it is for that thing to do its job.”

He looked up the calibration test for my serial number. That particular frisker had measured 3,000 counts in a 10-microsievert field. The correct figure was 3,200 counts. “So it’s just a little under, but within the typical range,” he said.

I inquired what their typical background radiation might be out there in Sweetwater. He said that at the factory they took in about 10 microrems per hour, which would be 0.1 microsieverts—more or less what I received in San Francisco or Tokyo, and half of what Ed Lyman got in his apartment in Washington, D.C. That sounded reassuringly plausible.

Perhaps the frisker read higher than the dosimeter for low values because it was picking up alpha and beta while the dosimeter could not. More likely, one or both suffered from a higher margin of error as the field approached zero. At any rate, the dosimeter’s measurements had corresponded, more or less, with officially reported values in Tokyo, Koriyama, Tomioka and Iwaki. The pancake frisker readings I took in the United States were comparable to the numbers that Ed Lyman and Eli had given me. Hoping for parity once I had entered a hotter field, I decided to be warned by whichever value of the two instruments was higher.

I further decided to use the SCALER mode in preference to the other two. There were many occasions in the red zones when I had to fall back to NORMAL, because it was discourteous to keep others waiting for a full minute time after time, all of us meanwhile absorbing radiation; and when I ascended the unpleasant stairs of the White Bird Shrine in Iitate I frisked my surroundings continuously, and thereby both got to record and to avoid the unhealthiest spots. But as often as I could do so considerately, I would make a one-minute timed walk in SCALER mode, or take a scaled measurement of such interesting objects as the drainpipe in Tomioka that Mr. Kanari had measured earlier that year with his municipal scintillation counter.

So I whiled away the months, hugely entertained by my pancake frisker. When I reached Japan, the first readings were no eerier than at home.

Tokyo. Japanese risotto restaurant, Kabukicho red light district. 33 cpms / 0.12 micros [once again, the same as my daughter’s cat].

As you might imagine, the red zones were hotter.

I used to get impressed by the difference between 0.06 and 0.18 micros an hour. At 0.36 micros, that granite countertop in Charleston certainly beguiled me. In Moscow, Molotov’s grave was three times hotter than Gogol’s—which in turn proved equivalent to the National Orchid Garden in Singapore. After going to the red zones I forgot to care about such piddling variations.

GRANITE AND PLUTONIUM

In terms of average radiation levels, Portland, Oregon, was certainly the healthiest city I visited (come to think of it, the little California town of Dunsmuir was just as good). As for the unhealthiest, well, the red zones more than overshadowed every other place I went in those days—including Hanford, Washington, where in September 1944 our government most secretly commenced to make plutonium. At first there had been three 800-foot-long separation facilities. Columbia River water kept the irradiated slugs cool at a depth of 16 and a half feet, flowing through the aluminum cylinders of the largest plant Du Pont had ever constructed. Downstream from there, eddies, bends, sediments and creatures grew “hot,” but war aims exempted our G-men and their pet scientists from responsibility from all such secondary issues. Had Japan been on a war footing 67 years later, Tepco might have been equally carefree about the contaminated outflows from Plant No. 1; I guess some entities are luckier than others.

(Here I wish to reiterate that no one with a heart can read unmoved the stories of those Tepco people who tried to deal with the catastrophe—for instance, Mr. Yoshida Masao, the chief of Plant No. 1, waiting for the containment vessel of Reactor No. 2 to possibly rupture, meditating on the floor, going through the names of his best-known colleagues: “There were about 10 or so. I thought those guys might be willing to die with me.”)

The atomic weapon that struck Nagasaki was named “Fat Man.” It contained 9 kilograms of plutonium. It is a thing of beauty to behold, this “gadget,” wrote the journalist who flew in the plane that dropped the bomb. We removed our glasses after the first flash, but the light still lingered on, a bluish-green light that illuminated the entire sky all around. So satisfied with that result was our government that production of the lovely silver metal continued until 1987; eventually there were nine reactors at Hanford.

An Atomic Energy Commission pamphlet from 1969 boasted that the Hanford reactors, then still creating or for all I know even satisfying demand, enjoyed environmental conditions more favorable than most power-plant . . . sites, being relatively remote from towns and . . . adjacent to the Columbia River, with its high volume of flow. The activated impurities got held for a good 1 to 3 hours, which reduces the activity by 50 to 70%. Then they got diluted by the streamflow. In the case of unusual radioactivity because of leaks of fission products, the water was discharged into trenches and seep[ed] into the ground. This percolation is very effective since the soil retains the radionuclides. And a diagram of the “underground crib,” decorated by “monitoring wells,” showed the plutonium on top of the rare earths, then the strontium, followed by the cesium, ruthenium and NO3.

Decades and trenchloads of “hot” river water flowed by under the slogan “the peaceful atom”; who am I to argue against such a delightful sentiment? For one thing, plutonium is less poisonous than arsenic, and perhaps even less hazardous than cesium-137 or strontium-90—although that judgment is more relative than it sounds, due to plutonium’s scarcity and chemical immobility.*

In practical terms, Hanford became the primary source for plutonium, thanks especially to the zealous industry of the N Reactor (built 1964), whose design approximated Chernobyl’s,* and except for small experimental quantities, it produced all the American-made plutonium that eventually reached the Northern Rio Grande system in New Mexico—through contamination, of course.—Let me now anticipate this book’s section on fracking, in which a consultant for resource extraction companies explains in Greeley, Colorado: “When you’re doing oil field, it’s not the fracking, it’s the piping. Things leak, things go wrong, when they have thousands of feet of piping in the surface. That’s human nature. I can’t go through a day without making a mistake; neither can they.”* Thus Hanford; thus Fukushima.—A guide for river paddlers called the site the most serious long-term threat to the Columbia River and the livable communities along its shores. Meanwhile The Japan Times praised Hanford thus: It’s among the most toxic nuclear waste sites . . . Apparently some 212 million liters of radioactive poisons had been cached in aging underground tanks . . . Gravel fields cover the tanks themselves, six of which had already been found to be leaking 1000 gallons . . . a year of highly radioactive stew, possibly reaching the groundwater—but for all I knew, they might have been more secure than King Tut’s tomb, thanks to the “big five”* miracle called “concrete cocooning.” The Japan Times article was even headlined: Hanford offers Tepco lesson in cleaning up Fukushima.

Suitably inspired, I decided to take a little frisk. Clyde in Richland had insisted that I would detect nothing of dramatic interest, but back when I was alive I used to be a curious sort.

According to a certain William L. Graf, whose Plutonium and the Rio Grande charmed me in the library stacks, sediments always contain the largest quantities of heavy metals, so that soils and sediments are the major repository for plutonium. Continuing his train of thought, Graf remarked that inhalation of plutonium-spiced sediments seemed probably the most important from the standpoint of human contamination. Well, then I would put on gloves and a painter’s dust mask, after which I could measure a couple of streambeds or gullies, with the frisker’s pancake head close to the ground. A Japanese nuclear engineer* advised me to measure both with and without the plastic cover, which was thick enough to prevent alpha and beta particles from reaching the device’s scintillating crystals. The difference between the two readings would reflect alpha and beta levels. Trusting myself not to detect that extremely scarce beta emitter Pu-241, which has no relevance to Carbon Ideologies, I settled for hunting the alpha in Pu-239, which had been employed in the MOX reactor at Fukushima, and should be Hanford’s dominant isotope—and in Pu-238, which in 2012 was detected in the Japanese red zones.

My detector was rated, said its spec sheet, at an efficiency of 11% for plutonium-239, so I figured I would need to divide whichever alpha number I got by 0.11 to obtain a rough plutonium level in counts per minute.* Later on, some nuclear Samaritan might provide me with the proper factor to convert this number to microsieverts.—Ed Lyman informed me that it would be more complicated than that. “You need to know the isotopics,” as he put it. I should send a soil sample to a lab for spectroscopy. That was the only way to learn the proportions of different plutonium isotopes, which would determine subsequent calculations.

I telephoned a dozen soil testing companies, and none of them would or could sample plutonium. I wish I had written down the stern and horrified things they said; it might be entertaining to learn how many of them then launched good-citizen e-mails to the Department of Homeland Security. Well, so why not just go to Hanford and see what I could see?

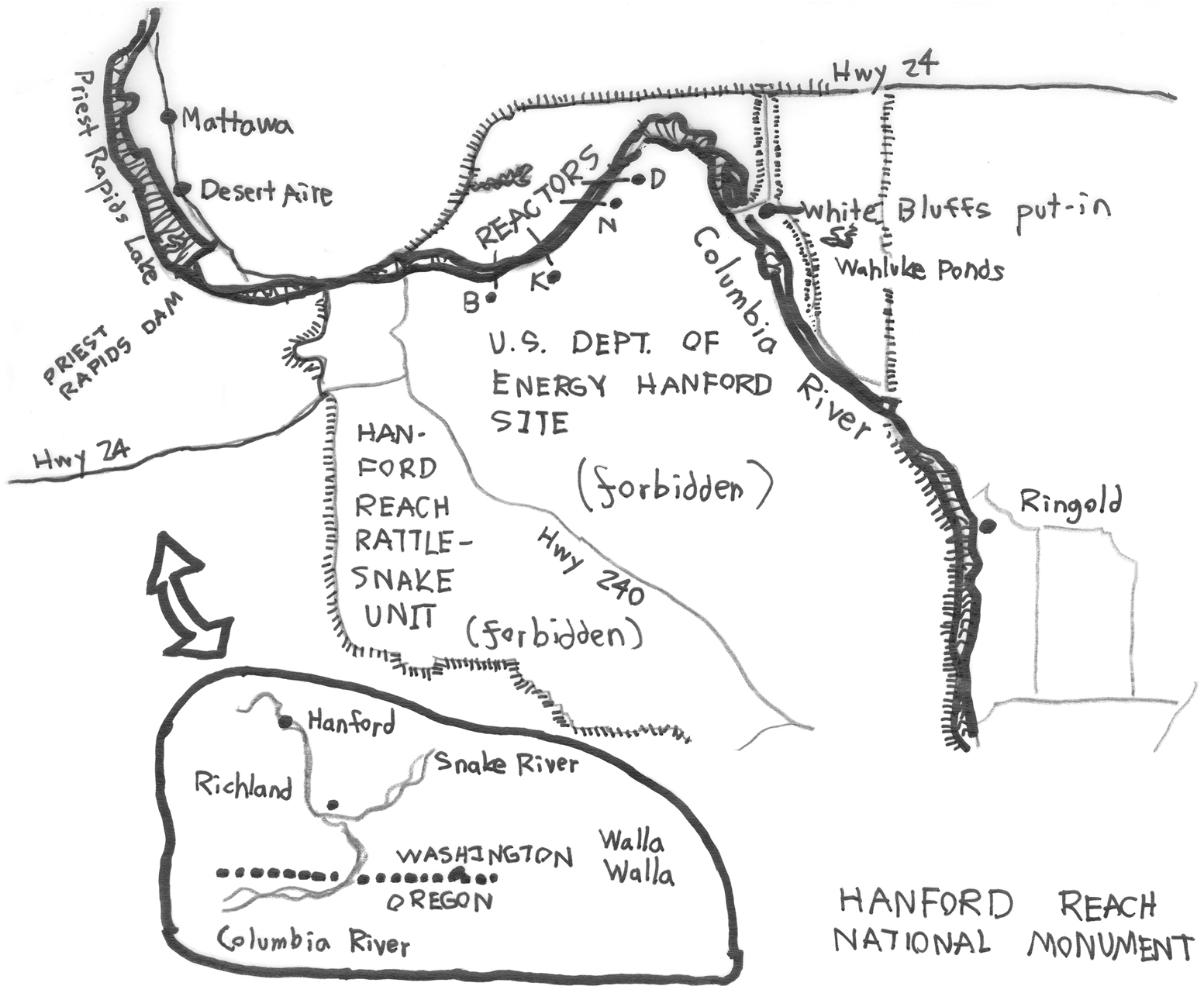

The drive from Portland took five hours. Arriving at a gate with a darkened booth, and a sign which ran: WHEN FLASHING TUNE TO 530 FOR HANFORD EMERGENCY INFORMATION, we turned south on Highway 240 toward smoke-hazed, dust-hazed Richland, where for all I knew Clyde was right then on his hands and knees in the back yard, happily frisking the grass; the temperature was 95° Fahrenheit. Rolling across the sagebrush flats, with the Hanford Reserve on our left for many a mile (there were only some 1,500 sq. km. of scrubland to search in—1,518 square kilometers, to be precise), we glimpsed well in from the fence a red-and-white radio tower—frequency 530, I assume—then two other slender white towers and a distant row of boxy white buildings—almost certainly not the reactors, which necessarily followed the south bank of the Columbia as it curved northeast before twisting sharply southeast along the White Bluffs. We ourselves were now angling more southeast than south on Highway 240, passing the brilliant whitish-yellow grass that was silver-pocked with sagebrush, and that long white fence so cheerfully decorated with yellow warning signs.

Below the reserve, not far past the southern extremity of Richland, we crossed the Columbia, came into Pasco and swung back northwest and north, paralleling the reserve’s eastern edge. Within another half-hour we had arrived at the put-out by the Ringold fish hatchery—one of the few places where our government would allow us to camp. This spot had received the highest fallout dose from Hanford—although most of it had been the extremely short-half-lifed iodine-131. My companion proposed stopping here, which was fine by me.—The Mormon crickets must have died off; for he said that two weeks earlier the river had been thick with them. The chirring of cicadas vibrated almost continuously through the buggy underbrush, and there was a fishy smell of muck, while there in the smooth lavender-grey river the sun lay reflected as a long orange bulbous-tipped wand not unlike the pancake frisker itself; and I felt (as I certainly never did in the red zones) so joyous and free in this novel part of my native land; no doubt in your time the heat must be worse at Hanford, and perhaps civil order has so far failed to let all 212 million plutonium-contaminated liters of progress seep out; I hope that those who cannot read remember from their grandparents not to go there. In my time it was a sweet enough place; since it was open to the public, I credulously believed myself safe, and my credulity got rewarded.

Directly across the river lay the widest sector of the reserve. I saw nobody on it, which failed to amaze me, because according to a pamphlet from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the Department of Energy’s side of the river, south and west shores, are closed above the high water line.

There on the shore the humidity had already begun turning cool, but when I strolled the few steps back up to our grassy campsite where Tom was looking over the motor of his beloved Water Witch it still felt almost sweltering.

Now it was nearly dark. Walking toward the trees, I commenced another measurement and then strolled back to the aforesaid Mr. Tom Colligan, who was a classicist and could explain exactly how difficult it might sometimes be to parse a sentence of Thucydides in Greek. While the frisker shone like a glowworm in the sweet-smelling grass, counting down to zero, I requested his opinions on Catullus, the coyotes meanwhile howling like young girls at a carnival, with a ring around that bright moon which tonight was so distinctly bat-winged with continents. I went to collect the frisker, which read 0.24 micros an hour, 72 counts per minute—identical to the library interior at Estes Park, Colorado.—And by the way, the presence or absence of the plastic cover never made a difference at Hanford.

Where trucks and boats were parked, and Tom had parked tonight, the level held steady at around 0.30 micros and 88 or 90 counts per minute (the same as a brickyard in Bangladesh).* Down toward the trees the dose fell off by 20%. It could have been that decades of contaminated Columbia River water dripping off of boats had increased the radioactivity, but that was the merest night hypothesis, and in the morning it proved incorrect.

I thanked Tom again for bringing me, and he passed me a beer and said: “Always happy to be out here where there’s nobody else.”

Mosquitoes kept biting my wrists, so I pulled my gloves on. Now it was chilling down pleasurably. We talked about Homer and ate meat with our nut-buttered bread until Tom felt ready to snooze in his truck. I fluffed out my sleeping bag in the mildly radioactive grass; Clyde might have reminded me that a truckload of bananas was worse. Tom had brought an inflatable mattress for me, but the grass was so soft that I used it only for a groundcover. The coyotes fell mostly silent. The moon was a fruit hanging from the black tree-spider just beyond that outspread its black arms in limp curves.

Mosquitoes annoyed us for most of the night, but before dawn the air chilled down farther, and before I knew it, morning woke me. Tom made us coffee and I brought jerky, berries and more bread with nut butter to the occasion. Then my friend strolled back down to the put-out. He said the river had strengthened enough that his motor might not be able to take us upstream; evidently Priest Rapids Dam had let out some water.

So we drove farther north and west, toward the White Bluffs put-out where (so Tom had heard from an old lady) there used to be a bridge, and before that an Indian crossing; once upon a time there had even been a town (the old lady claimed to have lived there), but the Manhattan Project expelled the inhabitants and razed the buildings, most likely for reasons of perpetual political security, although radiation levels might have had something to do with the action. The day was warming quickly. Could we have gone straight our route would have been 10 miles northeast, but it took us more than 15, and I was just as happy—for we were in a lovely land, following R-24 almost west through the yellowish-greenish sagebrush, crossing a concrete irrigation ditch, heading toward the lavender haze (some of which must have been from forest fires); and to the north lay a low glowing ridge the color of grass.

Entering Grant County, we soon neared the entrance of the reserve, where a helpful sign advised us: FIRE DANGER EXTREME. A dirt road brought us suddenly to good pavement—installed, I should guess, for the benefit of the U.S. military—and then we reached our turnoff above the White Bluffs boat ramp, with the Columbia a wide grey line to the west. According to the map, we were four miles as the crow flies from D Reactor, which lay across the 90-degree bend above which the Columbia flowed northeast.

So we backed down to the ramp. The Water Witch easily entered the water; Tom knew his business. When I waded into the lovely cool water and took hold of the painter, a dead salmon goggled at me. Tom drove the truck back up the road to park and lock it, and I gazed at a squat pale building across the river, wondering if it might be the lowermost reactor, while a white heron or egret bowed its neck far away. Up where Tom had gone, a doe slowly crossed the road, stopped, looked back over her shoulder, then carefully pranced into the underbrush.

I felt happy, not only because it would be fun to learn the frisker’s sensitivity to plutonium isotopes, but also because according to Tom’s river guidebook, the leg from Priest Rapids Dam to Ringold Springs, if done from the Vernita Bridge, runs along the longest wild and free-flowing, non-tidal section of the Columbia River in the United States . . . Keep in mind the U.S. Department of Energy prohibits public access to many areas of the Hanford Reach National Monument . . .

Tom returned, and seated himself in the stern. I waded out a little, pushed us off and crawled into the bow. He started the motor, and we were off.

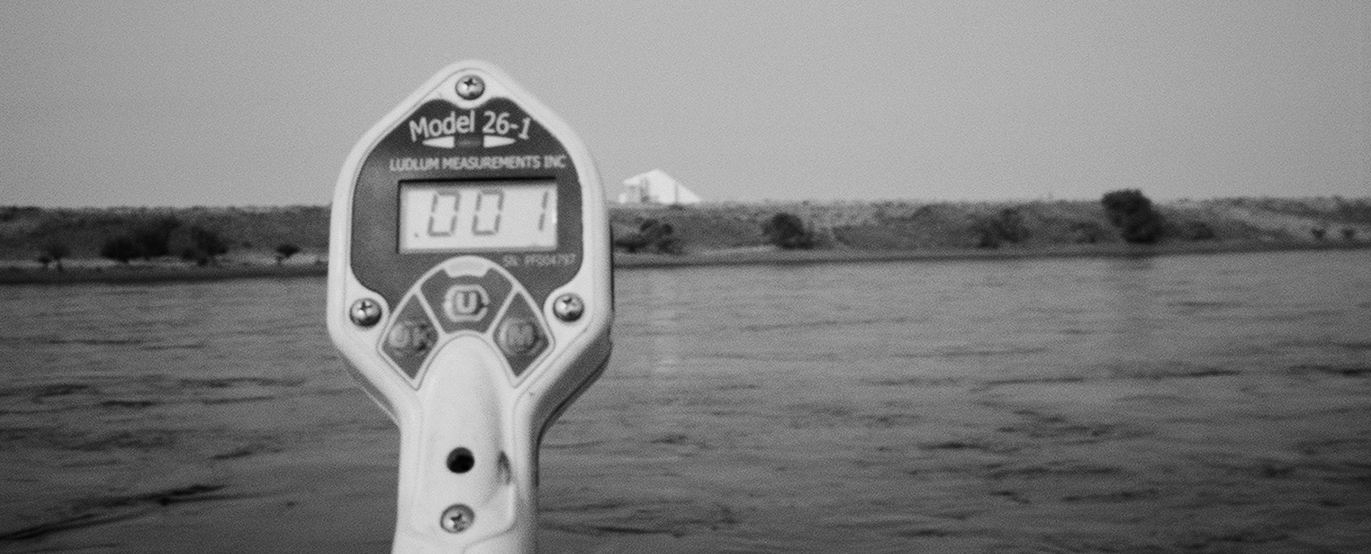

I had a dosimeter, too, of course; I kept track of every stray emanation I could.* In our 20 hours at Hanford, we accrued 1.6 micros of gamma radiation, or one micro per 12.5 hours; for that I could have stayed in bed! In my 39 and a half measured hours in Portland I took in 2.3 micros—a micro every 17.2 hours. So at Hanford I soaked up gamma rays one and a half times faster than in Portland—a minuscule difference, especially since at Hanford I was almost always outside, in Portland mostly inside, which certainly reduced my dose. So how did one factor that in? The proper thing to say was that from the standpoint of gamma rays, at least, Hanford was insignificantly “hot.”

Looking down through the dark water at the many-fingered hands of weeds, I listened to the motor, which was just loud enough (and we were far enough apart) for Tom and me to need to shout at each other if we wished to be heard; so mostly we let each other be. He looked pleased to be back out on the smooth glassy river, whose calm-appearing substance flowed so powerfully around the Water Witch that in places she could barely move upstream at all. A great silent fish splashed downstream near the restricted bank; and almost level with us sat a grey car, possibly containing a security guard. If I could, I would keep you here with me in this glorious if merely semi-wild place, instead of luring you into the red zones. But in my day I had to earn my keep, which meant informing my fellow planet-spoilers why it was hopeless; so at 8:57 a.m., with the building that Tom thought might be the lowermost reactor now enlarging off the bow, I set the frisker on MAX and held it out into the wind until 9:13. The highest reading was 1.184 microsieverts an hour, a laughably safe level which would not have been out of place as a one-minute timed SCALER average in a jetliner still ascending to cruising altitude. Multiplying this figure by 24 yields 28.416, which estimates the amount of radiobiological damage one would have accrued at this exposure over a full day. Receiving a month’s dose in a day might be considered vaguely unfortunate—but it was not a month’s dose, merely the extreme upper bracket of what the frisker sampled. I remembered from earlier that summer a certain walk of approximately 10 minutes’ duration in Saint Petersburg, whose levels were slightly higher than Moscow’s but still within the healthful or at least “normal” range; and going west along the Nevskii Prospekt on that breezy June afternoon, with the frisker set on MAX, my readings never exceeded 150 counts per minute, or about four times the average air dose of Sacramento—until as I crossed the Anichkov Most the count suddenly jigged straight to 480 counts per minute, or 1.579 micros per hour. Perhaps a cesium particle from Chernobyl had flown up against the frisker’s recessed circle-grid, whose crystals waited to scintillate—but the previous evening, when I had held the frisker straight into a wind on a Neva cruise boat as we neared the Peter and Paul Fortress, a full one-minute timed average measured only 26 counts per minute, 0.001 micros in that period (the lowest possible reading), which is to say 0.06 micros per hour, so I pronounced that Russian breeze salubrious. The likely cause of that scintillation was the Anichkov Most itself. It was a fine granite bridge, and some of the highest radiation levels I found in “safe” cities all around the world derived from granite:*

LOWEST AND HIGHEST MEASURED ONE-MINUTE AVERAGE RADIOACTIVITIES IN SELECTED SAFE CITIES, 2014–15

[in microSv/hr]

All readings were one-minute timed SCALER counts. By their nature, MAX doses read higher. [The highest MAX in Saint Petersburg was 1.579.] These and NORMAL readings are omitted since they were more ephemerally accurate.

Where several values were tied for highest or lowest, I picked whichever might interest you.

The range above each city name (for instance, “4” for Barcelona) is simply the highest reading divided by the lowest.

Range: 1.3

Singapore

Marble-tiled bathroom of suite, Grand Park City Hall Hotel: 0.18

Same suite near window: 0.24

Reason for high reading: Unknown.

2

Dunsmuir, California

Sacramento River, from bridge: 0.06

Nearly all locations: 0.12

Reason for high reading: It was delightfully low, actually.

2

Poza Rica, Mexico

Entrance to PEMEX refinery during small oil burnoff: 0.12

Table at Enrique’s Restaurant, near tile wall: 0.24

Reason for high reading: The ceramic tile, I suspect.

2.5

Dhaka, Bangladesh

Interior of room, Pan Pacific hotel: 0.12

Bricks in brickyard: 0.30

Reason for high reading: Bricks always measured high. See San Francisco.

2.5

Lausanne

Vineyard above Lake Geneva: 0.12

Granite wall, Jardin de Veant: 0.30

Reason for high reading: Three guesses. First one begins with “g.”

4

Barcelona

Subway L3 in motion toward Plaçade Catalyuna: 0.06

Air dose inside massive stone entrance tunnel, Montjuïc citadel: 0.24

Reason for high reading: Almost surely the stone. More usually, enclosed and especially subterranean spaces (such as the subway L3 noted above) measured very low. This is the rationale for a fallout shelter.

4

San Francisco

Intersection of Haight and Ashbury streets: 0.06

Brick tiles in backyard garden: 0.24

Other objects at this garden were up to 4 times “cooler.”

4

Pineville, West Virginia

Cow Shed restaurant, plastic bench: 0.12

Granite “Ten Commandments” tablet at courthouse: 0.48

Reason for high reading: Probably not any one commandment.

4.5

Denver, Colorado

Interior of Irish Snug pub on East Colfax: 0.12

Granite boulder in Denver Botanical Garden: 0.54

Reason for high reading: Not much of a puzzler.

4.7

Estes Park, Colorado [7,522 ft]

Trunk of blue spruce tree, bank of Fall River: 0.18

Lichened granite boulder off Highway 34: 0.84

Do you see a pattern yet?

7

Greeley, Colorado

Interior of Mad Cow restaurant: 0.06

Concrete loading dock near railroad tracks, old downtown: 0.42

Reason for high reading: Some mineral in the concrete aggregate, I would guess. The air dose in the same place was nearly 40% less.

9

Moscow

Marble floor of cafeteria in Tretyakov Gallery: 0.06

Granite curb of Molotov’s grave: 0.54

Reason for high reading: Well, he was a glowing old Bolshevik.

16

Saint Petersburg

Air dose in wind on cruise boat, Neva River near Peter and Paul Fortress: 0.06

Granite windowsill outside fancy cafe Kutsov Eliseevi on the Nevskii Prospekt: 0.96

I rest my case.

Typical air dose off the Hanford Reserve, downstream of the B Reactor

Slapping mosquitoes on my face, I toggled the frisker to a one-minute timed SCALER count, with a building that Tom thought might be D Reactor now off the bow at the 10:00 position, and got an air dose of 26 counts per minute, 0.06 micros an hour—the latter being once again the lowest reading possible.* My other frisks of river wind at Hanford yielded comparable results.

Looking upstream toward the chalky ridge on the northeastern bank—one of the White Bluffs, in fact—and the low olive grasses on the other shore where the reserve was (I saw a pelican on the forbidden side, and then mincing longnecked egrets, none of them diving yet, just watching the dark water), as Tom’s boat hummed over the water-weeds, which sometimes resembled corals or rock concretions, I now began to be pelted by caddis flies, which clung in hordes to my arms and shoulders, crawling inside my spectacles, hiding in my hair, sunbathing on the pancake frisker and thronging in the oarlocks. Tom was brushing them off, too, grinning a little; and slowly the Water Witch overcame the current of that creamy river. My friend had remarked on how deserted it always was out here; he’d called it a silent river, although come afternoon the fishermen might be out. Everything was hazy, muted and gentle, the river crabbed and crowded with ripples, caddis flies crawling on us, the pallid reactor (if that was what it was) growing and growing off the bow almost like a farmhouse. Dark vehicles crawled along what appeared to be the baseline of that structure (there must have been a road flat against the horizon). I could faintly taste wildfire-smoke on my tongue. Drawing level with the building, I took a MAX reading, then another timed count, followed by a series of NORMAL readings: 0.103, 0.051, 0.124, 0.079, 0.099 micros per hour; another near-identical timed count, and then we neared two yellow signs side by side, one in English and one in Spanish. Through the binoculars I made out the English-language one:

WARNING

HAZARDOUS AREA

DO NOT ENTER

Past the two signs was a dull-looking pale shed behind some power poles, with a white truck parked in front, and that long low graveled bluff before it, gently descending upstream; to tell the truth, the scenery was much prettier off to starboard with those cliffs of soft greyish-pinkish white, underlined by a long island of olive-green which resembled parts of the off-limits side. I saw a huge white bird, probably a heron. (As I revise this paragraph on an electrically-lit January night, with my words hoarded in a battery-powered device whose consumption of energy I have quantified here, I remember how as we motored upstream that island seemed to be sliding by itself, leaving the sand-cliff behind it untouched, because the latter was so much farther away.) Two MAX counts both read 81 cpms and 0.266 micros—nothing to write a book about. Squishing cold caddis flies on my forehead, with the boat droning upstream toward the bend where the White Bluffs and the reserve’s olive-green seemed to meet, I immediately took another one-minute timed SCALER sampling, with the usual results, my feet pleasurably cool in their dripping shoes; while on the Hanford side eight deer grazed close together just above the shore, watching us without fear, right by a tall sign labeled 14; then we passed more deer almost silhouetted on the bluff’s flat top; there looked to be a road up there. In a black tree sat a silhouetted osprey. There came a yellow sign too small to read, after which the bluff top had been fenced off for a good hundred yards; maybe waste tanks had been buried there, so that might have been a good place to frisk, but the bluff’s gravel remained smooth and even, with no sign of any creek or gulley to sample from. Here the bluff began to rise, its gravel still evenly sloped and now overlined with a long dark stripe that must definitely have been a road. A sign announced that we were entering Area 13. The bluff momentarily dwindled into a marsh, rising again up at the bend; then far back on the plain were more of those odd whitish buildings; and Tom now thought that these might be the reactors.

There was a pumping station, with a curving road behind it, on which two white vehicles were parked side by side, until one followed the other down the bank, and they both vanished behind the station. A vast flock of tiny black birds—cliff swallows, I should guess* (all silhouetted, too tiny for my binoculars to make out)—rushed over the reserve. It was 10:59, and the frisker read 0.06 micros an hour, 26 counts per minute. Just past the pumphouse, by another English-Spanish pair of yellow warning signs, with my three-minute MAX reading almost the same as before, Tom announced that we had better turn back; the current was getting too strong. It became evident that we had never even reached D Reactor, having come about four curving miles, with another three to go. But since the entire Columbia was supposed to be contaminated, anyplace downstream of the reactors should do.

Two hundred yards below the pumphouse we might have made a hypothetical landing, but that would have been illegal, so let us call the rest of this paragraph a work of fiction as Tom paddled us close, and I stepped out, frisking pebbles on the beach while the Water Witch slowly began to descend the stream. The one-minute timed count was about as I had expected: 45 cpms and 0.12 micros. After all, the pebbles were river-licked and not particularly porous. In the dirt up on the bluff, where I never went because that would have been even more illegal, was deer scat and yellow grass, with a reading of 65 counts per minute and 0.24 micros—pretty close to the edge of the trees at our campsite. Chasing after Tom’s driftboat, I reentered nonfiction.

At 11:50 we could have made another hypothetical landing, although of course I love authority and must respect all laws. Up on the flat plain where mulleins grew in towering isolation and that mysterious boxlike structure looked out at me, with a tall skinny entity behind (Tom had thought it an emergency siren) and the predictable sign proclaimed Area 13, I could fictionally have measured sandy soil at 52 cpms and 0.24 micros, after which, covering my face, I might or might not have troweled a two-inch-deep hole and frisked again, in which case the frisker would have read 66 cpms and another 0.24 micros.* There were many more hypothetical caddis flies here on land, and I was glad to get back onto the Water Witch and push us off. Then for awhile Tom happily fished on the river with a red lure that dove and jittered, as he told me about the big steelhead that got away.

Tom on the river

About three miles downstream lay a good muddy place I would have liked to sample, since it lay on the shore of the reserve, where radiocontaminants might tend to wash down from the bluff and maybe even stop and sink—because plutonium dioxide, you see, is heavy, its density being 11.46 grams per cubic centimeter, while common quartz is only 2.5; unfortunately, just then a busload of approved individuals appeared, so it seemed best to keep this landing even more hypothetical than the others.

At 1:00 p.m. exactly (the dosimeter at 578.6, up from 578.3, when we had embarked at 8:41 a.m.) we emerged from the river at the White Bluffs boat ramp. I had not heard of any law against “fishing around,” so I did just that. Remembering the following rule to live by, courtesy of William L. Graf: Heavy metal concentrations are usually highest in the finest stream sediments, I took my trowel and commenced to scoop up black mud and water at the river’s edge, just below the surface.—Why the water? Because, at least at Los Alamos, plutonium content of suspended sediment is greater than that of bedload sediment.

Two days later, when that watery mud and muddy water had dried somewhat, in the kitchenette of my Portland hotel room I opened the bag and frisked it: 35 counts per minute, 0.024 micros an hour. Clyde was right. I might as well have frisked my own back yard!

Frisking a bag of mostly dried Hanford mud

I consoled myself with this finding of William L. Graf’s: The grand mean concentration for plutonium-238 in river water from the six major regional sites (on Rio Grande) is nearly zero . . . and the mean concentration for plutonium-239 and -240 is 0.0041 pCi/l, a value close to the minimum level of detection.* In which case, why not fight global warming with plutonium fuels?

CONCERNING BIOLOGICAL CONCENTRATIONS

The Japanese anti-nuclear engineer Hirose had noted (and in his book he spoke specifically of Hanford) that even after the radioactivity of waterborne particles decreases, the danger (or, as energy technologists might call it, the benefit) will continue to concentrate in plankton, and accumulate still more in the plankton-eating fish.

Hanford’s plutonium, then, might well have built up in the tissues of various organisms. I did not know how to measure those.

The following illustrates this phenomenon in the case of other Hanford pollutants:

CONCENTRATIONS OF RADIOACTIVE PHOSPHORUS AT HANFORD NUCLEAR SITE,

1954–58

[in milligrams per gram]

In Columbia River: 0.00003*

In egg yolks of ducks and geese: 6

CONCENTRATION FACTOR = 200,000*

OTHER CONCENTRATION FACTORS AT HANFORD,

1954–58

[also in milligrams per gram; original water concentrations not given]

Cesium-137

From waste pond water to muscle tissue of waterbirds: 250

Iodine-131*

From “desert vegetation” to thyroids of jackrabbits: 500

Strontium-90

From waste pond water to bones of waterbirds: 500

Sources: Eugene P. Odum, 1971, citing Foster and Rostenbach, 1954; Hanson and Kornberg, 1956; Davis and Foster, 1958; with calculations by WTV.

The pancake frisker failed to detect any of these radiocontaminants at Hanford—doubtless because they had been dissolved or suspended in such dilute concentrations.—The case of potassium was sobering.—The concentration factors for iodine, cesium and strontium bore grim relevance to Fukushima, where all three of those had been detected after the accident.

As Eli had told me, “The hotter the field is, the easier it is for that thing to do its job.” “That thing” certainly found its job easier in the red zones. When you consider the radiation levels I discovered there, please consider concentration factors. Imagine being encouraged to return to your home in Tomioka. Remember that the pancake frisker was optimized for cesium-137. Consider that much or most of the radiation I measured derived from this isotope. Multiply my readings by a factor of 250, and imagine bearing that amount of radiation in your muscle tissues.

And my failure at Hanford raised another unpleasant question, which will be germane to all subsequent chapters of Carbon Ideologies: What other dangerous substances right in front of me was I unable to detect?

All I could do was my best. On that subject, I had already learned from Mr. Kanari* that in the red zones, bricks and granite dwindled in importance; drainpipes were a better object of the frisker’s attentions:

Frisking a grating in Tomioka

MEASURED RADIOACTIVITIES OF SELECTED DRAINPIPES AND SEWER GRATINGS,

2014–15

[in microSv/hr]

In “normal background” areas

Sacramento

• Sheet metal pipe down the side of my studio: 0.12

Sidewalk 5 ft from same: 0.18

Charleston, West Virginia

• Grating in asphalt parking lot, Budget Host Hotel: 0.12

Asphalt curb 2 ft from same: 0.18

Williamson, West Virginia

• Drainpipe on side of Ryan & Ryan, attorneys, at ground: 0.18

Grass 1 ft from same: 0.24

Estes Park, Colorado

• Metal drainpipe, measured at sidewalk: 0.15

Concrete sidewalk 1 ft from same: 0.36

Barcelona

• Grating at Passeig de Sant Joan (frisker turned on its side): 0.18

Maximum air dose (sampled over 5 minutes) in vicinity of same: 0.08

Saint Petersburg, Russia

• Thick, painted, cast iron (?) pipe down courtyard wall of Hotel Nevsky Forum: 0.18

Sidewalk directly below same: 0.18

• Painted drainpipe down side of cafe Kutsov Eliseevi on the Nevskii Prospekt, frisked where it crossed exterior granite window-ledge: 0.54

Window-ledge adjoining same: 0.96

In Japanese green zone

Hisanohama [16 km north of central Iwaki]

• Drainpipe of traditional Japanese house being decontaminated: 0.49*

Rain channel in concrete driveway of same residence: 0.16*

• Next door neighbor’s drainpipe: 0.17*

In Japanese red and yellow radiation zones

Iitate

• Decontaminated drainpipe: 4.00

Roadside vegetation near same: 1.048

Tomioka

• Grating on border of green and yellow zones, frisked at 1 ft: 3.01

• Drainpipe near TSUBA, frisked at base, February 2014: 22.1*

• The same, frisked 1 ft from ground, October 2014: 12

• The same, at ground level, October 2014: 32

Air dose 2 ft from same, October 2014: 5

Okuma

• Grating near Ono Station, frisked from 3 inches above: 4.20

Air dose nearby, continuously sampled: 6–10

• Another grating in vicinity, frisked at 1.5 ft: 11.52

• The same, frisked at 10 inches: 21.9

• The same at 8 inches: 23.3

• Rusty grating at fish hatchery (deep drainage well beneath), frisked at waist level: 20.0

• The same at 3 inches: 30.0

Air dose in vicinity: 9.46

And now, reader, you are as numerically prepared as was I to visit the red zones.

THE RULES

Regarding these interesting places I should express my admiration as an American citizen—for when I lived we believed in “states’ rights”: In certain zones two women could marry each other,* or a cancer patient could legally drink marijuana tinctures for his pain, or a gun owner could stroll down Main Street loaded at the ready, while in other parts of the same nation any or all of those things were forbidden—that their rules of entry so colorfully varied. The red areas of Tomioka could be permissibly entered only through a national call center whose policy seemed less than favorable to non-residents. As for Okuma, that seaside paradise now rendered even more salubrious by the presence of Nuclear Plant No. 1, one could apply directly to the municipality, a written process that took months and required an exact route to be pre-approved, a vehicle (in this case another $600 taxi), a guarantee that each member of the party would possess protective gear and a dosimeter, and of course the construction of the most satisfactory answers to certain questions. In my case, for instance, it seemed better for me to be an author than a journalist, and best of all for me to be a photographer, as indeed I was. An official car would escort me, to ensure that I kept all my promises. So I anticipated a blinkered, commanded experience. But when push came to shove, nobody cared if my driver or interpreter had dosimeters; the driver even declined my offer of shoe covers, a mask and a paper painter’s suit. He was supposed to remain in the taxi at all times, so he got out whenever he felt like it, taking happy breaths of sea air and tramping through the radioactive weeds. Smiling, he said: “Just write that I stayed in the car.” (Now I have.) Once we had exited the red zone through the final security gate, the interpreter and I were sent for decontamination, while the driver and the two municipal officials (who had led rather than followed, and obligingly allowed me to wander around wherever I liked) stood passing the time, unmasked in that presumably particulated breeze. My painter’s suit, I sadly report, immediately tore across the crotch, while my shoe covers, which had soon become pincushions of significantly radioactive stickleburrs, stayed on until we were in view of No. 1, at which point the left one finally tore off. So there I was, ponderous and ludicrous, frisking the world with one hand while I photographed and scrawled notes with the other. I suspect that those two officials, so elegantly unencumbered, quickly lost whatever respect they might have felt for me, not that I much cared. Soon enough I had unzipped my paper suit halfway down the chest; except when we were admiring No. 1, from which an ill wind blew; I left my mask dangling around my throat (the prudent interpreter wore hers, although when we dropped by Tomioka later that day she put it on backwards, presumably inhaling whatever Okuma fallout had accrued to it, at which we both had a good laugh); so I was an unkempt shambles of a foreigner, but at least I could not later accuse myself of protecting my health more than did the people who were helping me. That was Okuma. In my university Russian language class our instructor, a Russian émigré, once joked that Russians were Italians trying to be Germans; and comparably peculiar were Okuma’s rules: strict in advance, mild in practice.

Iitate and Namie occupied still another category, for each of these places opened itself to me by means of a private tour. My guide for Iitate headed the Nagadoro subdistrict, which owned the unfortunate distinction of being the only part of the village actually in the red zone. When we approached the security gate, I asked whether he had obtained permission from the central government to bring me in.—“You’re not really allowed,” he explained, “but I will take responsibility.” How I loved that answer!—As for Namie, there too a kind of tour materialized—this one with a former Tepco worker who believed in nuclear power.

BUSINESS AS USUAL

In the summer of 2014 I entertained myself at home, cooking soup on my fossil-fueled stove, flying to the West Virginian coal country and generally doing my mite to burn more carbon while I awaited the approval of my Okuma application. Wishing to someday become a canny journalist, I even read the newspapers. That was how I kept up with Japan.

In April, Tepco’s attempt to freeze radioactive water in a tunnel between Reactor No. 1’s turbine building and a contaminated trench achieved disappointing results. I wasn’t awfully surprised.

A June headline ran: Tepco’s ice wall runs into glitch.

No matter how hard they tried, they could not seem to lower the temperature far enough. Since July they had injected, they said, more than 400 tons of ice and dry ice.

In August, an equal 400 tons of groundwater were still flowing into the reactor’s basement every day. There it got spiced up with cesium. That month Tepco petitioned to construct a facility to dump radiation-tainted groundwater . . . into the sea—but don’t worry, it would be after filtration, of course.

Then came another headline: Ice wall at No. 1 plant fails.*

Two weeks before my return, Typhoon Phanfone added its mite (168 millimeters of rain) to the groundwater around the four reactors of Plant No. 1, so that a monitoring well between Reactor No. 2 and the ocean now presented 150,000 becquerels per liter of tritium, a record for the well and over 10 times the level measured the previous week. That was very special.

The day before I arrived, what seems to have been the same well set a new record: 251,000 becquerels per liter of cesium—a concentration 3.7 times greater than four days earlier. It was the highest recorded in water samples from any of the wells. And, oh yes, strontium-90 and other such beta emitters had also increased their presence, to 7.8 million becquerels per liter.

I interviewed some Tepco P.R. men that month, and one of them, a Mr. Hitosugi Yoshimi, set my mind at rest on this issue: “We do sampling of the ocean water, and all of the results are publicized on our website. From immediately after the accident, if you compare to now, it’s much lower. It’s almost unmeasurable; that’s the fact.”—When he was saying these things I felt as sorry for him as I had for my hometown utility spokesman who could not bring himself to mention global warming.*

And poor Tepco kept working away. What else could they do? They could hardly sit pretty, as the U.S. Department of Energy had at Hanford. The plan was to clear away explosion debris from Reactor No. 1 in the winter of 2015. In 2013, they had attempted this at Reactor No. 3, incidentally contaminating various rice paddies with fallout. Maybe it would go better this time. If it did, then sometime in late fiscal 2017, they could attempt to withdraw No. 1’s fuel rods.

The tsunami that wiped out the backup cooling defenses of the four reactors at Plant No. 1 had been 15.1 meters high. Certain number-crunchers now projected that a 26.3-meter tsunami might strike the site—perhaps tomorrow, maybe 10 or 100,000 years from now. If that happened, said Tepco, 100 trillion becquerels of cesium could reach the ocean. It would certainly be nice to decommission the reactors before that took place.

They hoped to clear away Reactor No. 4’s fuel rods by November. And on another wonderful note, No. 1 fuel rod removal to finish ahead of time, Tepco chief says.

In fact the news grew so good that the Nuclear Regulation Authority approved the restart of a two-reactor plant in Kagoshima Prefecture.

As for me, I bought spare batteries for the pancake frisker, and stocked up on those cheap painter’s suits I have mentioned; frisker tests would establish that they could indeed keep the alpha and beta particles off my clothes. Perusing The Japan Times, I learned enough to hunt for swallows with white spots and peculiarly sized butterflies. (I saw the second but not the first.)

It was October, and the cities and ricefields grew ever foggier as the bullet train shot northward. In Koriyama the white fog resembled smog, and the buildings looked as ugly as ever. The air dose from the train platform was no worse than Tokyo’s, although a few days later my walk around the block measured 0.30, .36, .42 and .54 micros an hour with the frisker out before me at waist level. Even the granite flagstones of the station plaza were less radioactive than some boulders I later frisked in the Colorado Rockies.—Proceeding to Fukushima City, where the average value of my 40 frisks would be 0.24 micros (about two-and-one-third times higher than my home town), I lay in my hotel bed, listening to the rising and falling of a negligibly radioactive wind.

The following table is expressed in multiples of the average radiation level in my home town, Sacramento. It may be interesting for you to compare this table with the one here.

The figures here seem less alarming than the ones in the other table. They are also less accurate. By making claims about the average radioactivity of a given municipality, as opposed to merely reporting what is emitted from this or that specific object, this table pretends to do what only an army of friskers could achieve in fact. To record a few measurements here and there, many of them from within a moving vehicle, is merely to suggest. So be it.

Red zone border marker in Tomioka (2.34 micros per hour)

COMPARATIVE AVERAGE RADIATION LEVELS, 2014

in multiples of the Sacramento average

(from pancake frisker data)

All levels expressed in [microSv/hour]. Headers over 10 rounded to nearest whole digit.

1

Sacramento [0.08 microSv/hr]. This equals 0.7008 millis/yr.

1.43

1 milliSv per year. Maximum dose for ordinary citizens, per the International Commission on Radiological Protection. [0.11416].

1.63

Tokyo and San Francisco [0.13*].

1.75

Poza Rica, Mexico [0.14].

2.13

Namie, Japan [0.17]. Based on only 3 measurements along decontaminated highway. Had I been given more time, I probably would have found significantly higher levels.

2.25

Aizu-Wakamatsu, Japan [0.18].

2.38

Hirono and Singapore [0.19]. Many of the 11 Hirono readings were taken in vehicles en route to Tomioka. Since Hirono lies north of Iwaki, I suspect that a more thorough and accurate sampling would have found higher radioactivity than in Iwaki.

2.50

Iwaki, and various places in West Virginia, U.S.A. [0.20].

2.85

2 milliSv per year. Japanese national target air dose (“1 additional milli”). [0.22832].

3.50

Fukushima City [0.28].

4.00

Koriyama and Naraha [0.32].

5.14

3.6 milliSv per year. Alleged average worldwide dose. [0.41095].

7.14

5 milliSv per year. “For an individual steadily receiving 500 millirads per year, the chance of dying from cancer or leukemia is increased by 30 percent.” Disputed. [0.570776].

16

Iitate outside red zone [1.24].

18

Commercial airline flights [1.43]. These readings include takeoffs and landings but exclude any runway measurements. At cruising altitude, where airplanes spend most of their time, but where I frisked less often, my measurements generally fell between 2 and 3 micros an hour, so a truer (less eclectic) sampling might have averaged more like 30 times the Sacramento figure.

29

20 milliSv per year. Lower limit of yellow [“residence restriction”] zone designation. [2.283].

29

Okuma outside red zone [2.35].

35

Tomioka [2.77].

39

Iitate red zone [3.12].

71

50 milliSv per year. Upper limit of yellow zone designation; lower limit of red [no-go] zone. [5.708].

89

Okuma red zone [7.14].

143

100 milliSv per year. 0.5 percent increase in probability of fatal cancer, if this dose is received for a year. [11.416].

7,441

100 milliSv per week. Emergency exposure limit for nuclear workers in Japan, 2014 (susceptible to upward revision, which the government was considering). [595.238 micros/hr].

12,673

U.S. Transportation Security Administration X-rays [1,013.82].

2: No Crime in Nagadoro

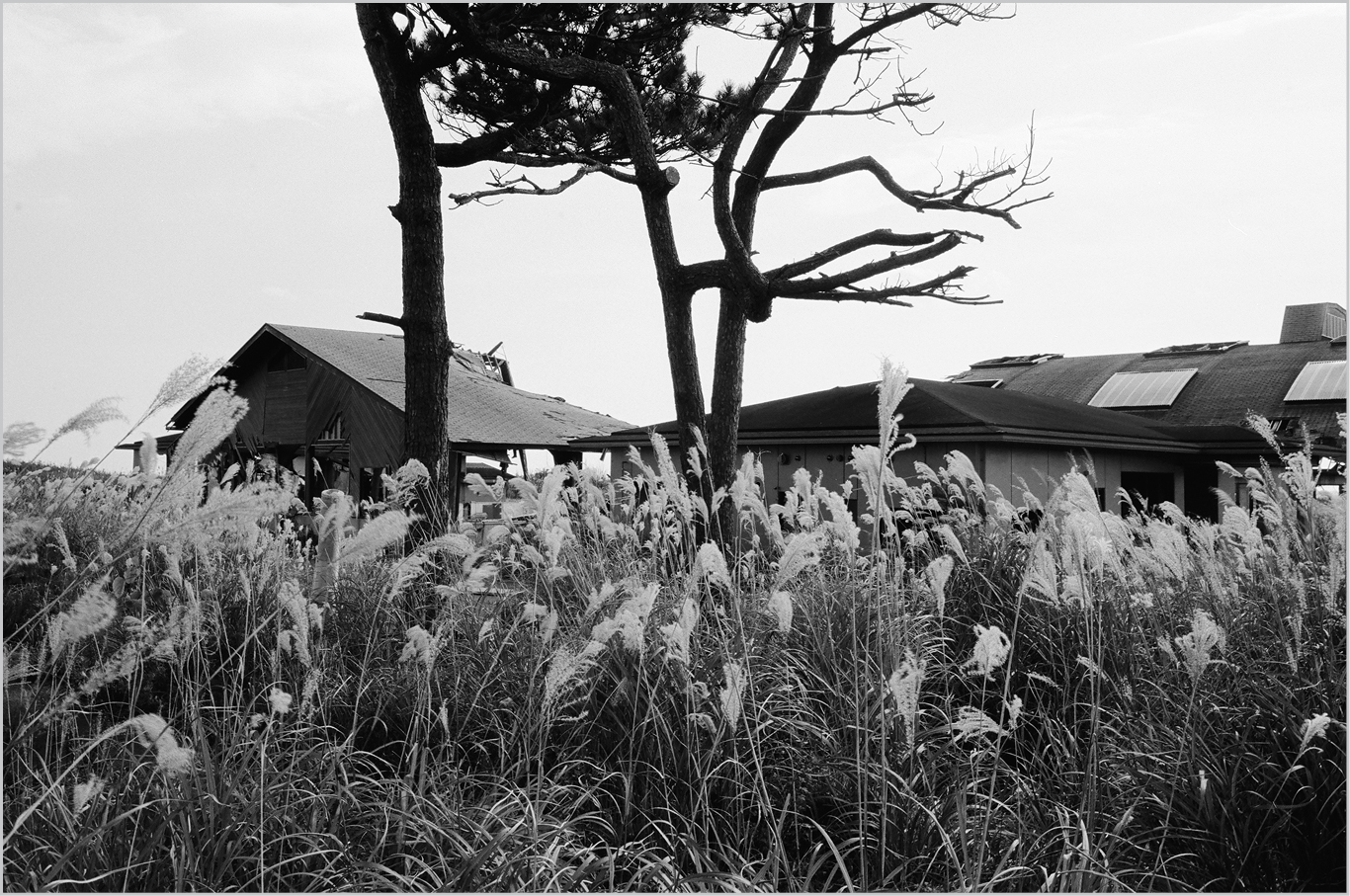

Although Iitate Village lay a good 40 kilometers from Plant No. 1, and might have been expected to be as safe as anywhere on the outer ring, the place proved unfortunate in its winds. Perhaps this was the case which persuaded the Japanese government to replace that convenient system of the two rings with a more realistic fallout map.

It was another “combined village,” like Tomioka. “We took one sound from each included area to make this name. First four villages became two, Odate and Iiso; so we took Ii and tate,” explained a man from Iiso; the two towns had joined “30 years ago, or maybe 50.”

You may recall that the pre-accident population of Tomioka had been 16,000 at most. As for Iitate, in 2016 someone mordantly remarked: There every day 7500 workers are “decontaminating” the village where 6500 lived.

Iitate apparently received its first cesium, iodine and tellurium* in a snowfall after the explosion of Reactor No. 3. It was the most distant of the 10 localities to be blessed from plutonium from the accident (Okuma, Minamisoma and Namie also got improved in this way). I remember in 2011 watching the weather reports on Japanese television; this village always figured in them. Some of its subdistricts grew more contaminated than others, Nagadoro being the most dangerous—which is why it owned the lonely distinction of being a red zone.

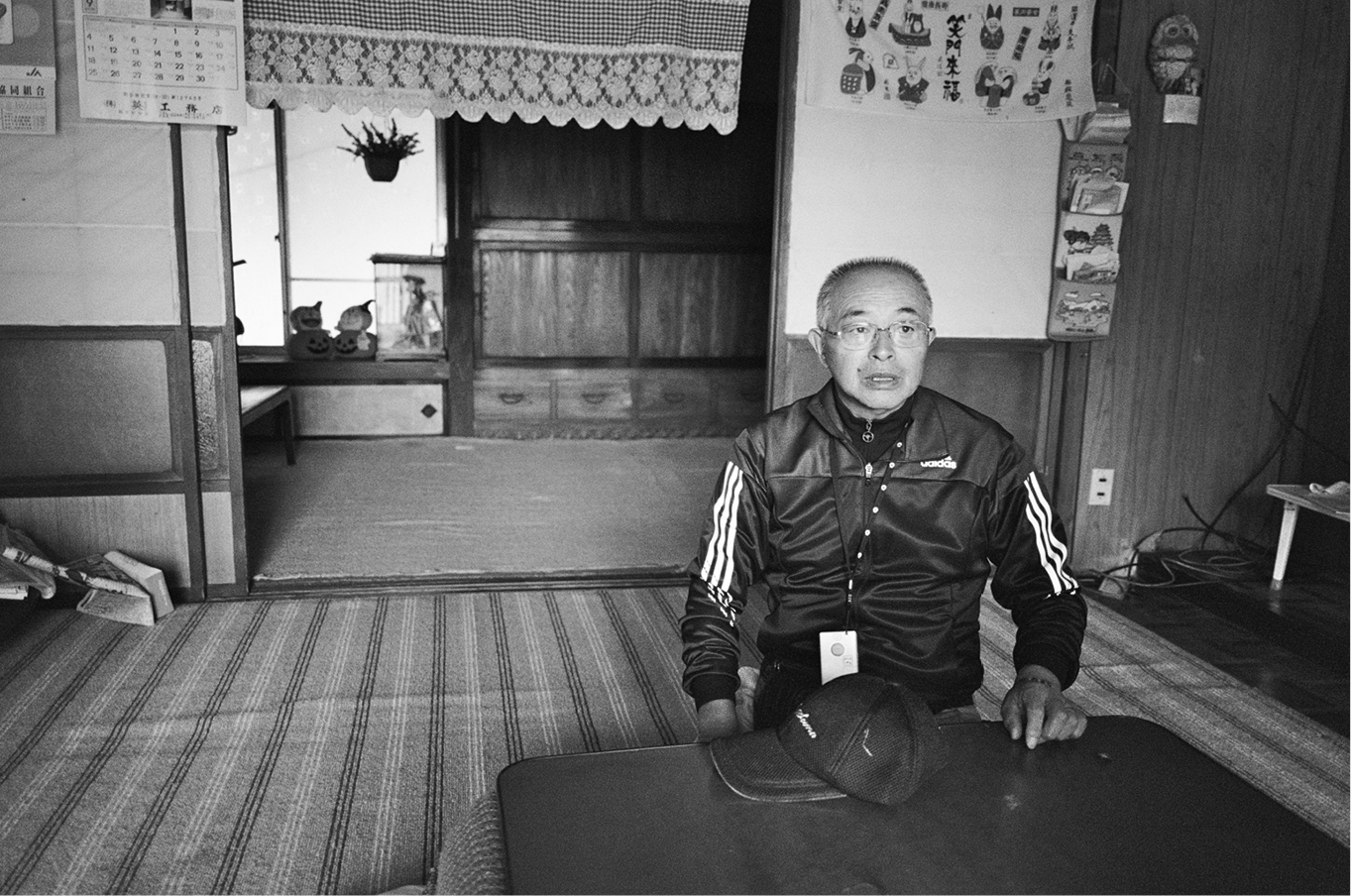

Mr. Shigihara Yoshitomo (the man from Iiso) was the head of Nagadoro. He had once been a welder. His household had contained six persons, including two grandchildren. On his dairy farm there had been four breeding cows and three calves—all sold on June 22, 2011.

He wrote that on March 15, 2011, when they were making riceballs, the radiation level was 44.7 micros an hour—slightly higher than my own worst reading ever in Fukushima. A day later it was 49, and the day after that it had reached 95.1. On April 6, a Mr. Takamura found 28,000 becquerels from soil in Nagadoro. Come the end of that month, the government announced that radiation accumulation in Nagadoro now exceeded 20 millisieverts.*

At that time, people were still allowed to stay in their homes, but not to eat what they had planted. As for the cattle, eventually they slaughtered nearly 3,000 head. All the same, everyone in Iitate had remained in Mr. Shigihara’s words free to come and go for 14 months after the accident. At the end of May 2012, compulsory evacuation measures fell upon them. Each of the Nagadoro people was to receive 6 million yen* a year for five years. When Mr. Shigihara told me this, I remarked on the difference between his compensation and Mr. Endo’s—for as you may remember, the latter got nothing, his house being insufficiently damaged by the tsunami. Mr. Shigihara replied: “The government policy is to isolate all the evacuees. If they are too powerful, they are against the government. At the beginning we were all united against Tepco, but not now.”

His family left home on June 22. On July 17, Nagadoro became a no-go zone. Mr. Shigihara believed that the subdivision of contaminated areas into red, yellow and green further separated the people from each other.

On July 4, a whole body counter found his exposure of cesium-134 to be 1,200 becquerels; he also bore 1,400 becquerels of cesium-137.—How badly was he poisoned? At Chernobyl a certain Colonel Vodolazhsky, who died from his injuries, is said to have received 600 becquerels, evidently on a single overflight of the reactor; and from context this appears to have been a very high level of irradiation. But I should note that the colonel made many other flights; hence this dose might not have been lethally carcinogenic in and of itself.—At any rate, Mr. Shigihara’s 1,400 becquerels could scarcely have been good news.

By 2013 he had begun to wonder whether decontamination were even possible. In a typescript which he prepared at that time, he noted the immense amount of time it required to decontaminate a place. In addition, he wrote, the resulting radiation level decrease is only to half.

Here are some other thoughts from that sad document:

What hurt me most is that I left my grandchildren exposed to radiation . . . I often say that the truth will be revealed when my grandchildren have babies. This is unbearable . . .

I feel we are now being tamed. There is no dream or hope. Nagadoro residents and Fukushima people are all supposed to be angry. I don’t really like “social movement[s],” but after experiencing this, I now think that we need to voice against what we think is wrong . . .

My house was built when I was a child, carrying logs from the mountains, and [construction] took 2 years. After all these years, you can’t easily leave the village, which was constructed through our ancestors’ efforts generation after generation.

His “young son” announced that he would never return to Nagadoro. The same went for his grandchildren. Saying that she could not imagine life without them, his wife informed him that in that case she would not go back, either. Mr. Shigihara: So I thought, there is no point for me to return there alone.

Think about it. Why [do] people gather and hold festivals at the shrine? Why do they dance? What is your home? I can’t explain well myself, but perhaps gratitude to the ancestors . . . I realized for the first time after I left my home. It is like you realize how you appreciate your parents only after they die.

That September he measured the levels again, reading 5 to 7 micros at the “Nagadoro intersection,” 4 to 6 micros both in front of and inside his house, and 8 to 15 micros in his ricefield and his vegetable garden; the latter two, he noted, had certainly fallen off.

I was to meet him on October 23, 2014. On the twenty-second, at 4:30 in the afternoon real time, according to the Nuclear Regulation Authority website, which a lovely Japanese angel accessed for me, it had transpired that of Iitate’s 40 monitoring posts the highest official value was the senior high school at 2.338 micros per hour; the junior high school was the merest 1.441; there even appeared to be a few zero points in the yellow zone. Then the angel’s cursor froze up; certain station values did not appear; should I have labeled that human error or was it the machine kind? I calculated that 2.338 micros an hour meant 20.48 millis a year, but I would hardly be in Iitate for a year, so who cared?—As it happened, 2.338 micros was an understatement. (Shall I say that the NRA lied, or simply that certain unmentionable things happen?)—On that cool afternoon of light grey rainy sky and dark grey concrete buildings it came time to consider the practicalities of one’s painter’s suit and half-face dust mask which was recommended for use against harmless dusts only; one also carried the shoe covers and blue gloves at the ready.

The twenty-third was a grey morning. I wondered if it were drizzling; then a cyclist rode by with an uncovered head, overflown by two crows. The next thing I wondered was whether sunscreen would adhere alpha and beta particles to my skin or in fact keep them from blowing down inside my clothes. Unable to guess, I skipped the sunscreen.

The dosimeter read 0.571 millisieverts accrued over more than a year in Tokyo—the usual a micro a day, or very rarely two. Before tonight, several more digits might turn over.

In the lobby of my business hotel, men bowed over their breakfasts at small round tables, one fellow, perhaps a student, for he wore cheap black clothes, rapidly chopsticking sticky rice from his plate into his upturned bowl. The other men were all dressed at least in stiff white shirts and black business slacks; some were in full suits, one of those latter, a balding chubby specimen, having just finished eating, wore a four-faceted paper mask over his nose and mouth as he sat with folded arms, rapidly tapping his feet; while behind him at the reception desk the plump young lady in the yellow pseudo-military uniform complete with black and gold epaulettes as required by that corporate chain stood waiting to give or take a key; and two meager-faced elder women in white blouses, green aprons and green kerchiefs carried dirty dishes to their den on the other side of the room, where they now began washing them. Faced down by a scene so stoutly quotidian, the red zones faded into the merest harmful rumors.

The railroad clock displayed 11.9° Celsius at 8:00 a.m. The bulky, jolly, headshaved taxi driver sped us over the half-dry river. He said: “I don’t mind about the radiation. It’s the younger ones who have to worry.” And so we arrived at the apartment block.

Mr. Shigihara was a roundheaded grandfather with very short spikes of grey hair. He said: “It hurts me when they say that radiation causes mutation. It hurts me that the government evacuated Okuma and Futaba but not Iitate. They first said that even 10 microsieverts per hour was no problem at all. At our community center it was 15 or 17 . . .”

To his young-looking wife I offered to frisk anything in their abandoned place that she might wish to have with her, but she calmly replied that the neighbors would be too frightened if it came out that she had brought anything back from there. She served tea. They seemed to be a loving couple. Their story had a typical village beginning: Her family’s home had been only 1.5 kilometers away from his. I thought it kindest not to inquire what had happened to her parents.

Mr. Shigihara remarked that the Nagadoro people hardly kept in touch anymore. “People from Okuma and Futaba, 70% of them are in the same place. From Iitate they are spread all around, because the other places were evacuated right away, and by the time we were told to leave, no good facilities were left.”

We got in his car, and I turned on the pancake frisker: the merest 55 counts per minute, 0.18 micros. That was higher than Tokyo and San Francisco but just barely lower than Singapore.

I asked what he used to do when he was a boy.

“We went after birds. There were no toys, you know. No swings! We made swings using big ropes. We played marbles. We just went into the mountains to make charcoal. At that time we didn’t grow much rice,” evidently for lack of flatlands, “so mountain jobs were more important. Forestry keeps you busy for the whole year . . .”—and we were winding up into the mountains, paralleling the sparkling grey-green river.

“We would sell the charcoal for cash,” he said. “You put the charcoal on the back of a horse and you walked 30 kilometers. That was what we did until the Tokyo Olympics in 1964. Then we started to go to other cities to work. In Iitate we earned 400 yen per day, and in Tokyo we could get 2,500 yen per day. From January to March there was nothing to do here; that was when people went away.”

We passed steep rock outcroppings, higher than in West Virginia. There were lush banana trees, rainy sky, high round hills of yellow-green forest. I wondered how contaminated they were.

“After the Olympic Games there was a company set up in Iitate to make electrical parts,” he was saying. “Women worked there and also in a garment factory . . .”

“When did you first hear that nuclear power was coming near you?”

“Forty years ago. I was about 20. That was when I heard about it. At that time Iitate Village was against it, but we had no say since the plant was more than 30 kilometers away. Futaba and Okuma* received many subsidies, but we got nothing.”

He might or might not have been a jealous soul, but he paid most definite attention to what he and his were given in relation to others.

He said: “In my opinion, the people who benefitted would like to go back by any means, but I think they should compromise a little bit; my grandchildren can’t go back.”

I saw bamboo and something like honeysuckle and a few trees turning yellow.

“The government says they are going to make a facility for temporary storage. I think that temporary and final storage should be the same,” he said.

“Whom do you blame?”

“The government, and nationalists, including me. I personally don’t feel responsible, but everyone blames Tepco and the government alone, and that’s wrong. Our parents, the earlier generation, they accepted it. Everybody including me is responsible. The government shows the least intention to be responsible. It doesn’t even want to decide threshold radiation levels for whenever we should go back to Iitate. They say that we should decide it, because they’re just trying not to take responsibility.”

“When do you think your home will be safe?”

“The head of the NRA*, Mr. Tanaka, he came to my house to carry out an experimental decontamination. At that time, he said that it would take at least 20 years. It was as if he were talking to himself. It won’t be good in 20 years . . .”

He added: “Around then the front of my house read 8 micros an hour. Mr. Tanaka said they would make it one-tenth, but they only reduced it by 50 percent. That made him so disappointed . . .”—and we were passing through the high town of Kawabata, whose cemetery steles glittered on the hills; just here (in the car, at least) the radiation was as low as in my kitchen back home.

“Up to here we used to sell charcoal,” he said. The dosimeter remained at 0.571.

Every little flat space had long since become a ricefield. We turned onto our mountain shortcut, lurching up into the red and yellow leaves.

“So Japan is going to deteriorate,” he said. “If you don’t take care of these fields and forests at the prefectural level, the water and air will not be remediated.”

We passed a field of scarlet maples, rolling uphill past the terraces.

He said: “I believe that if the nature is beautiful, then even if the living level is economically lower, it’s still a better life.

“There is no name for the road,” he said. “We are almost at the border of Iitate.”

Suddenly we were in a forest of cryptomeria and pine which to me appeared quite wild, although Mr. Shigihara said that it had been planted only some 30 years ago. He said: “I don’t wear a mask, nothing. The government, I don’t see many of them wearing masks . . .”