Shannon M. Monnat and Raeven Faye Chandler

Demographic data confirm that the United States is, indeed, a nation of immigrants. As early as 1850, immigrants1 represented nearly 10 percent of the U.S. population. More than 41 million immigrants now live in the United States, representing 13.1 percent of the total population. Immigrants remain geographically concentrated in traditional gateway cities such as Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Houston, and Chicago (Migration Policy Institute 2015). However, recent geographic dispersion of immigrants from these traditional gateways, and directly from other countries, to southeastern and midwestern suburban and rural communities with little recent experience with nonwhite immigrants has generated hundreds of scholarly works on new rural immigrant destinations over the past fifteen years. Despite these changes in the distribution of immigrant origin countries and settlement patterns, newcomers today struggle no less than their nineteenth-century predecessors with social, residential, and economic integration. Moreover, recent immigrants to the rural United States may face even greater economic difficulties, including higher poverty rates, than their peers in metropolitan areas. There are several reasons for this, including that most new rural immigrant destinations lack significant native-born exposure to immigrants, employment prospects are more limited in some new destinations, and newcomers are at risk of social and economic isolation due to small co-ethnic populations and residential segregation (Crowley and Ebert 2014; Lichter 2012; Lichter, Sanders, and Johnson 2015; Marrow 2011).

This chapter summarizes the history of immigration to rural America and describes rural immigrant population change over time. County-level census data are used to describe the distribution of immigrant poverty across rural America, highlighting differences in immigrant poverty rates between rural counties with historically large immigrant populations (“established immigrant destinations”), counties without historically large immigrant populations but substantial immigrant population growth since 1990 (“new immigrant destinations”), and rural counties without large or high-growth immigrant populations (“nonimmigrant destinations”). Comparisons are made of the human capital characteristics of immigrants and labor market factors that may be associated with variation in immigrant poverty across these different types of rural destinations.

HISTORY OF IMMIGRATION TO RURAL AMERICA

U.S. immigration policy has been a touchstone of political debate for decades and remains a hot-button issue in current politics. Contemporary immigration controversies mostly surround Mexican immigrants. This was vividly highlighted in this statement made by Donald Trump in his 2016 presidential campaign announcement speech: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people” (Trump 2015), as well as this statement Trump made during the final Presidential debate: “We have some bad hombres and we’re going to get them out.” Trump’s campaign promises to build a wall between the United States and Mexico and to deport the millions of undocumented immigrants living in the United States have continued since he took office.

Though denounced by many, Trump’s sentiments about Mexican immigrants and his proposed deportation policies struck a chord with a non-negligible share of U.S. citizens concerned with the economic implications of recent Mexican immigration, particularly in the aftermath of the Great Recession from which many parts of the United States are still recovering. However, hostility toward immigrants has not always been targeted at Mexican immigrants. Before the 1960s, most immigrants came from Europe, and they too stirred controversy. This section describes historical trends in rural immigration, factors contributing to those trends, and controversies surrounding U.S. immigration policy. Data are from the Migration Policy Institute (2015) Data Hub, the U.S. Census Bureau historical census statistics on the foreign-born population of the United States, 1850–1990 (Gibson and Lennon 1999), the Decennial Census 2000 (U.S. Census Bureau 2000), and American Community Survey 2009–2013 (U.S. Census Bureau 2015).

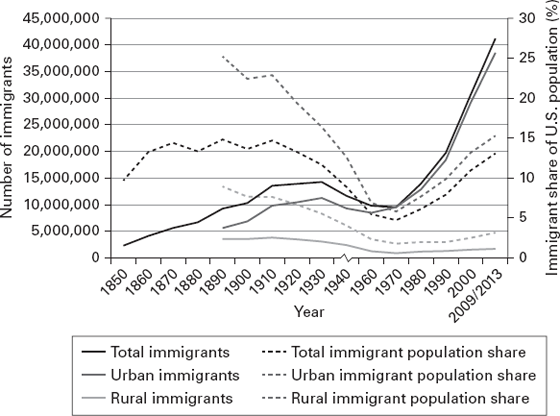

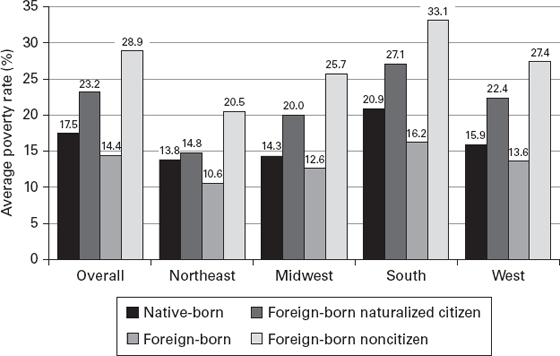

Figure 7.1 U.S. immigrant total, urban, and rural population and share, 1850–2009/2013.

Sources: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) Data Hub, 2015 and U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850–1990, Table 18; Decennial Census 2000; American Community Survey 2009/2013.

Note: U.S. Census Bureau did not report the immigrant urban and rural population shares until 1890 and did not provide data on the urban and rural population for 1950.

Migration to the United States has fluctuated significantly over the past 120 years (figure 7.1). After peaking at 14.8 percent in 1890, the immigrant population declined to a low of 4.7 percent in 1970 but has increased rapidly since the 1970s. As of 2013, 41.3 million immigrants (13.1 percent of the U.S. population) were estimated to be living in the United States. Immigrants to the United States have historically been drawn to large metropolitan gateways that house large populations of co-ethnic nationals. In the late 1800s, about a quarter of the urban population was foreign born compared to 9 percent of the rural population. Immigrants still comprise a larger share of the urban population (15.3 percent) than the rural population (3.2 percent), but the absolute number and share of immigrants in rural areas is larger now than at any time since 1940.

Immigrants of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were almost entirely of European origin. Between 1880 and 1970, however, the European share of immigrants declined from 86.2 percent to 61.7 percent, and European immigrants now represent just 11.9 percent of the total immigrant population. The share of immigrants from Latin America, on the other hand, increased from just 1.3 percent in 1880 to 19.4 percent by 1970, and Latin American immigrants now comprise over half (52.5 percent) of all immigrants in the United States. Latin American immigrants (particularly those from Mexico) make up an even larger share (two-thirds) of all nonmetropolitan2 immigrants (table 7.1). However, immigration from Latin America, especially Mexico, has leveled off over the past decade, attributable in part to the economic recession and improving economic conditions in Latin American countries. Asians are now the fastest-growing U.S. immigrant group. There is little research on nonmetropolitan Asians, but they comprise a non-negligible 16.5 percent of nonmetropolitan immigrants. They are concentrated almost entirely in Hawaii, university towns, and refugee resettlement communities.

Table 7.1 Nonmetropolitan Immigrants by World Region of Birth, 2009–2013

| Region |

Total |

Percent of total nonmetropolitan immigrant population |

| Africa |

37,760 |

2.20% |

| Asia |

283,705 |

16.50 |

| Europe |

216,992 |

12.62 |

| North America |

72,077 |

4.19 |

| Oceania |

16,513 |

0.96 |

| Latin America |

1,092,168 |

63.53 |

| Mexico |

881,177 |

80.68 |

| Other Central America |

113,792 |

10.42 |

| South America |

46,489 |

4.26 |

| Caribbean |

50,710 |

4.64 |

| Total |

1,719,215 |

|

Source: American Community Survey, 2009/2013.

Note: Percentages for Mexico, other Central America, South America, and Caribbean use Latin America total as base.

FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO RURAL IMMIGRATION TRENDS

Immigration reflects interrelated economic, political, and social shifts occurring at global, regional, and local levels (Durand, Massey, and Charvet 2000; Massey and Capoferro 2008). Although the specific reasons for migrating to rural areas of the United States vary across groups over time, U.S. migration has historically been economically driven. The first large group of migrant farmworkers in rural California was the Chinese, who were imported to build the transcontinental railroad and subsequently recruited by large farms as cheap labor. By the early 1880s, the Chinese represented 75 percent of seasonal farmworkers in California (Martin et al. 2006). The great wave of European immigration to the U.S. Northeast and Midwest in the late 1800s, which included the Polish, Germans, Scandinavians, Italians, Greeks, Slavs, Scottish, and Irish, was driven largely by the desire to escape poverty and overpopulation in Europe and the promise of economic prosperity in the United States, including opportunities in farming, timber harvesting, and coal mining (Cance 1912; Glazer and Moynihan 1963; Lichter 2012; Zeitlin 1980). The motivation to earn a living and provide for one’s family that drove European migration in the 1800s and early 1900s is mirrored today among immigrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries who wish to do the same.

Although early European immigrants, especially non-Protestant Jews, Irish, Poles, and Italians, were not considered white and often suffered xenophobic exclusion and ethnically based discrimination, restrictions barring immigrant entry to the United States during its first 100 years were minimal. Restrictions focused instead on limiting the entry of “undesirable” immigrants, including prostitutes, low-skilled contract workers, and the Chinese, especially during the late 1800s and 1920s. Moreover, the U.S. government has traditionally made exceptions to its immigration laws to increase the supply of immigrant labor for agriculture and related industries such as meat packing and food processing (Martin et al. 2006). Several such immigration policies since the 1940s contributed to contemporary rural immigration flows, particularly immigration from Mexico. Chief among these was the Bracero Agreement (1942–1964) between the United States and Mexico that permitted Mexican nationals entry to the United States as temporary agricultural workers during WWII labor shortages in exchange for stricter border security and the return of undocumented Mexican immigrants to Mexico. The program also called for wage guarantees, housing, and food, but these terms were often disregarded by U.S. farm operators. Under the program’s terms, Mexican workers were allowed to stay in the United States for up to six months, and the program placed caps on the number of migrants who could enter the United States. However, illegal recruitment practices among U.S. farm operators, and food shortages, labor conflicts, and population growth in Mexico, resulted in longer stays and continued illegal border crossings, including the migration of laborers’ family members to the United States (Martin et al. 2006; Massey and Liang 1989). Rapid growth in undocumented, predominantly low-income, and poorly educated Mexican migrants prompted the U.S. government to implement “Operation Wetback”3—rapid-response tactics to quickly deport laborers and their families and keep Mexicans from entering the United States. The program was short-lived, as U.S. farm owners continued to illegally recruit low-wage undocumented workers.

Following the Bracero program, Congress passed the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act (1965), which favored family reunification and skilled immigrants and imposed the first limits on immigration from the Western Hemisphere. In 1986, Congress enacted another major law, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which focused on penalizing employers of undocumented migrants and increasing border patrol. IRCA’s stepped-up border controls did make illegal entry into the United States more expensive and dangerous, but it failed to deter young Mexican men from entering, and it kept those who succeeded in crossing in the United States longer.

In addition, approximately 2.8 million undocumented immigrants were legalized under IRCA through two programs. The general legalization program legalized 1.7 million undocumented immigrants who had been in the United States since January 1, 1982. The Special Agricultural Worker (SAW) program provided a pathway to citizenship for farmworkers who completed at least ninety days of farm work from 1985 to 1986 and resulted in the legalization of 1.2 million farmworkers, 90 percent of whom were Mexican (Martin et al. 2006). With the desire to escape highly populated cities, rising housing costs, and crime, and with the pull of new low-skill employment in low cost-of-living areas, some of these newly legal residents traveled beyond the West to cities and small towns with previously small or nonexistent Latin American immigrant populations. Many undocumented residents, who were family members, friends, or coworkers of the newly legalized residents, followed (Martin et al. 2006).

Increasing U.S. and international demand for processed and prepackaged foods drove new employment opportunities for immigrants. To meet growing demand and cut costs, factory operators found ways to deskill and routinize production. Many relocated their plants from the heavily unionized Northeast and North-Central United States to the rural Southeast and Midwest where agricultural inputs were closer and land and labor was cheaper (Kandel and Parrado 2005), thanks to successful union-busting by major players such as Hormel and Oscar Meyer decades earlier. This restructuring of the food processing industry led to widespread recruiting of nonunionized, low-skill immigrants from California and Texas and directly from Mexico and Central America (Gozdziak and Martin 2005).

These economic drivers, along with increasing hostility toward immigrants in southwestern states, the now greater danger associated with crossing back and forth over the border, and restrictive local and state policies (e.g., California’s Proportion 187 in 1994), contributed to unprecedented Hispanic (mostly Mexican) migration from urban settlements in the West to rural destinations in the Midwest and Southeast throughout the 1980s and 1990s (Johnson and Lichter 2008; Kandel and Cromartie 2004; Lichter and Johnson 2006; Massey 2008; Parrado and Kandel 2008; Singer 2004). Many immigrants bypassed traditional destinations altogether and migrated directly from their sending countries to the rural United States (Lichter and Johnson 2006). To be sure, large cities, especially Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, retain the bulk of the U.S. immigrant population and continue to experience the majority of immigrant population growth (Lichter and Johnson 2006). However, at 3.2 percent, immigrants currently comprise a larger proportion of the rural population than at any time since the 1940s. Although the rural immigrant population is small relative to the urban immigrant population, the geographic diversification of immigrants has transformed the face of the rural United States and raised questions about the economic and social incorporation of newcomers into rural communities and in U.S. society more broadly.

RECENT RURAL IMMIGRATION

In this section, recent trends in rural immigration are presented using data from the 1990 and 2000 Decennial Censuses of Population and the 2009/2013 American Community Survey (ACS) five-year estimates.4 The county is the unit of analysis. Counties are designated as metropolitan or nonmetropolitan using the 2013 United States Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (USDA, ERS) Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. Using the 2013 classifications ensures that the analyses are restricted to current nonmetropolitan counties. Counties that were once nonmetropolitan but had enough population growth by 2010 to be classified as metropolitan are therefore excluded.

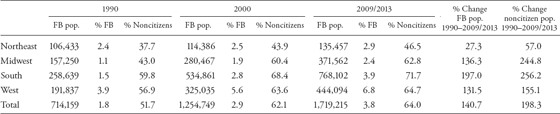

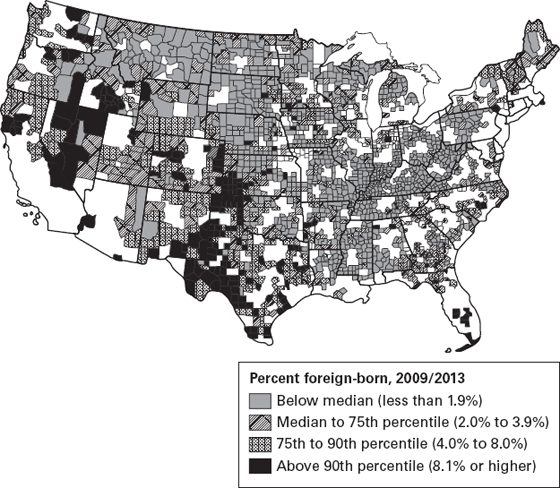

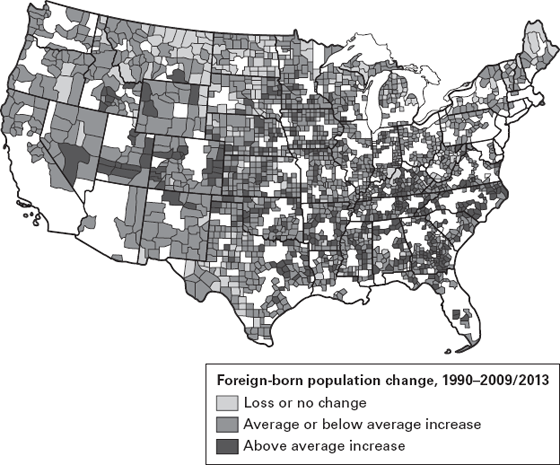

The distribution of nonmetropolitan immigrant population growth varies significantly by region. These trends are illustrated in table 7.2 and figures 7.2 and 7.3. Whereas the nonmetropolitan Northeast experienced a foreign-born population increase of just 27 percent between 1990 and 2009/2013, the foreign-born population more than doubled in the Midwest, South, and West. The percentage of immigrants who are not naturalized citizens5 also increased in all four regions between 1990 and 2009/2013, with the largest increases in the Midwest and South. Increases in noncitizen immigrants are important because noncitizens are at higher risk of poverty, which is discussed in more detail later.

Table 7.2 Nonmetropolitan Foreign-Born Population by Region, 1990, 2000, and 2009/2013

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Decennial Census 1990 and 2000 and American Community Survey, 2009/2013.

Notes: % FB = percentage of total population that is foreign born.

% noncitizens = percentage of total foreign-born population that are not naturalized U.S. citizens.

Figure 7.2 Percent foreign-born in nonmetropolitan counties, 2009/2013.

Source: American Community Survey, 2009/2013.

Figure 7.3 Foreign-born population change in nonmetropolitan counties, 1990–2009/2013.

Source: Author calculations using data from Decennial Census 1990; American Community Survey, 2009/2013.

Nearly half of nonmetropolitan immigrants live in the South, and over three-quarters are Latin American (mostly Mexican). Over half (51 percent) of immigrants in the South reside in Texas, and 74 of the 198 counties with foreign-born populations above the ninetieth percentile are in Texas (figure 7.2). Counties in other southern states, particularly Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi, however, experienced the most foreign-born population growth between 1990 and 2009/2013 (figure 7.3). This is largely the result of the movement of processed food and textile production facilities from the Northeast to the South throughout the 1980s and 1990s, which drew low-skill immigrant workers seeking escape from low-wage seasonal farm work in the West. For example, in the late 1980s, Mohawk Industries, which specializes in flooring manufacturing, moved its production from central New York to Gordon County, Georgia. Shaw Industries, the largest carpet manufacturer in the world, is also a large employer of immigrants in Gordon County. As a result, 5,140 immigrants resided in Gordon County by 2009/2013, whereas the county was home to just 225 immigrants in 1990.

In the nonmetropolitan West, the foreign-born population is most pronounced in Washington, Oregon, northern and east-central California, New Mexico, Nevada, Colorado, and Idaho. Although immigrants have dispersed from the West to other parts of the country, the nonmetropolitan West experienced immigrant population growth of 131.5 percent between 1990 and 2009/2013, and immigrants remain most concentrated in the West. Wasatch County, Utah, is an example of a county with rapid immigrant population growth driven by economic factors. Whereas only 69 immigrants lived in Wasatch in 1990, more than 2,500 immigrants lived there in 2009/2013. Tourism, a major employment industry for immigrants, comprises much of the economy in Salt Lake and Summit counties, which border Wasatch. Also, some of the 2002 Winter Olympic events were held in Wasatch, increasing the demand for low-skill labor in the tourism and recreation industry.

A number of midwestern nonmetropolitan counties also experienced above average foreign-born population growth between 1990 and 2009/2013 (figure 7.3), especially in Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, mid-southern Minnesota, and eastern South Dakota. In all midwestern states, however, there were nonmetropolitan counties that experienced immigrant population loss, perhaps because earlier migrants to those midwestern counties relocated to other midwestern counties for new employment opportunities. Dawson County, Nebraska, which experienced an increase from just 138 immigrants in 1990 to 4,391 immigrants in 2009/2013, is a good example of midwestern immigrant population growth. Tyson Fresh Meats, which began operations in Dawson County in the early 1990s, along with Frito-Lay and Monsanto, employ large numbers of low-skilled immigrant workers in Dawson.

Finally, the Northeast contains the smallest share of nonmetropolitan immigrants. Just 7.8 percent of all nonmetropolitan immigrants live in the Northeast. Immigrants in the Northeast are the most likely to be naturalized citizens and the least likely to be from Latin America. In 1990, several nonmetropolitan counties in New England were home to comparatively larger foreign-born populations than in 2009/2013, attributable almost entirely to migration from Canada. By 2009/2013, only a handful of New England counties remained home to significant immigrant populations (figure 7.2). These include Aroostook County in northern Maine; Clinton, Essex, and Franklin counties in northern New York; Caledonia County in northern Vermont; Coos and Grafton (home of Dartmouth University) counties in New Hampshire; and Franklin County in Massachusetts.

RURAL IMMIGRANT POVERTY IN THE CONTEMPORARY UNITED STATES

Poverty has historically been and remains a fact of life for a large share of U.S. immigrants. Between 1960 and 2000, the poverty rate among immigrant-headed households increased from 14.1 percent to 17.4 percent, whereas the poverty rate among native-born households declined from 20.9 percent to 11.8 percent (Hoynes, Page, and Stevens 2006), but this trend may be changing. Between 1994 and 2000, poverty rates fell more quickly for immigrants than for native-born households (although immigrants maintained higher rates of poverty), and immigrants experienced greater increases than native-born households in real median family income (Chapman and Bernstein 2002). However, this was a period of strong U.S. economic growth (after the early 1990s recession and before the early 2000s recession). Moreover, these national poverty estimates are driven by metropolitan poverty because most of the population lives in metropolitan areas. Data constraints such as these often make understanding rural immigrant poverty more challenging.

In this section, the current distribution of immigrant poverty across the nonmetropolitan United States is described. Although the presentation is limited to nonmetropolitan counties, it is important to note that a large proportion of immigrants living in metropolitan counties cross county boundaries to work in nonmetropolitan counties (Martin et al. 2006). Therefore, employment opportunities and conditions in nonmetropolitan areas affect metropolitan immigrant poverty rates as well.

There is substantial spatial variation in nonmetropolitan immigrant poverty (figure 7.4). There are clusters of especially high immigrant poverty in the eastern and southern gulf areas of Texas, southern North Carolina, New Mexico, eastern West Virginia, southwestern Arkansas, and northern Montana. Conversely, there are clusters of especially low immigrant poverty in Vermont, central Maine, southern North Dakota, and southern South Dakota. Of note, no counties in New England are in the highest quartile of immigrant poverty, which likely reflects both the low representation of Latin American immigrants (especially Mexicans) in New England and the stronger economy in some New England states (Vermont, Connecticut, Massachusetts) relative to the rest of the country.

Figure 7.4 Foreign-born poverty rates in nonmetropolitan counties, 2009/2013.

Source: American Community Survey 2009/2013.

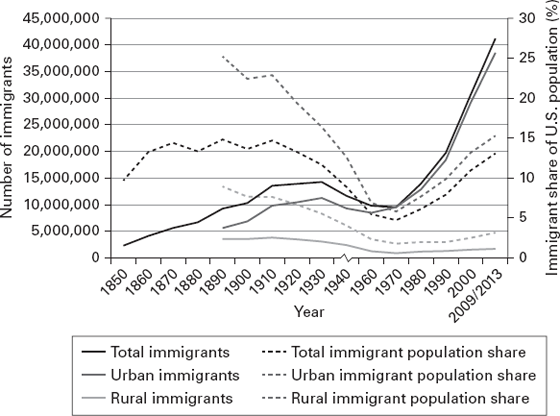

Figure 7.5 presents average county-level poverty rates overall and by region for nonmetropolitan counties with at least 100 foreign-born residents6 (all racial/ethnic groups) for native-born, foreign-born, foreign-born naturalized citizens, and foreign-born noncitizens.7 The average foreign-born poverty rate for nonmetropolitan counties is 23.2 percent compared to 17.5 percent for native-born residents, but the foreign-born disadvantage is driven entirely by high poverty rates among noncitizens. Whereas the average poverty rate among naturalized citizens is only 14.4 percent, it is 28.9 percent among noncitizens.

Figure 7.5 Nonmetropolitan county average poverty rates for native and foreign-born residents by region, 2009/2013.

Source: American Community Survey 2009/2013.

Note: Among counties with at least 100 foreign-born residents (N=1,477).

Citizenship affects poverty risk in at least two ways. First, most immigrants who are not naturalized are not eligible for federal poverty relief programs, including Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).8 Under current safety net program policies, most immigrants must be lawful permanent residents (LPRs) for at least five years to qualify. States may choose to provide safety net services to immigrants who are ineligible for federal programs by fully funding those services themselves, but most states currently do not have these programs (Pew Charitable Trusts 2014). Even when programs are available, immigrants may be reluctant to apply for fear it will jeopardize future citizenship, they will be required to repay costs, or they will be deported. Lichter et al. (2015) provide evidence of these deterrents, showing that only 9.9 percent of poor rural Latino infants who are born in the United States (and are therefore U.S. citizens and eligible for safety net programs) reside in families accessing government cash assistance. These current policies both increase poverty risk during periods of job loss and medical emergency and increase the likelihood that immigrants will be subject to involuntary part-time work and marginal jobs, which predominate in rural areas (Findeis and Jensen 1998; Lichter and Crowley 2002). Indeed, although labor force participation is higher among immigrants than among the native born (Grieco et al. 2012), immigrants—particularly noncitizen immigrants—are at higher risk of involuntary part-time and short-term work than native-born workers (Slack and Jensen 2007). The second related way that citizenship status can affect poverty is through employer treatment of immigrant workers. Undocumented immigrants currently have few legal protections against employer abuses, including wage theft, and they may fear that reporting employer abuses could lead to deportation.

The South has the largest share of noncitizen immigrants, particularly from Mexico. These factors may partly explain why the South has the highest average nonmetropolitan immigrant poverty rates among the four regions (figure 7.5). Mexican immigrants are at especially high risk of poverty in rural areas because they are typically young, are uneducated, have limited English proficiency, are often undocumented, and often work in low-wage and seasonal jobs, particularly in the South (Effland and Butler 1997; Martin et al. 2006). High poverty rates in the rural South, in general, reflect the lack of union presence, much lower wages, and less industrial diversification relative to southern urban labor markets and rural labor markets in other parts of the country (Lichter and Jensen 2002).

In all four regions, high noncitizen poverty rates drive average foreign-born poverty rates higher than average native-born poverty rates. The gap between the average naturalized citizen poverty rate and noncitizen poverty rate is smallest in the Northeast at 10 percentage points and largest in the South at 16.9 percentage points. It is noteworthy that, in all four regions, the naturalized citizen poverty rate is lower than the native-born poverty rate because the native-born rate includes groups with historically high rates of poverty, including African Americans in the South and Native Americans in the West.

COMPARISONS OF RURAL IMMIGRANT POVERTY IN ESTABLISHED, NEW HIGH-GROWTH, AND NONIMMIGRANT DESTINATIONS

Beyond regional differences, it is important to consider how poverty varies between immigrants residing in rural areas with long histories of immigration compared to places with little previous experience with immigrants but recent rapid immigrant population growth. Both destination types are present in all four regions of the United States. New destinations differ from established gateways in many ways that create challenges for immigrants to new rural destinations. New destinations have less access to support networks; limited, crowded, and poor-quality housing; limited access to reliable transportation needed for traveling to work and services; residential isolation; and linguistic challenges associated with living in communities where most residents have never interacted with non-English speakers and are sometimes hostile to foreign-born, especially nonwhite, newcomers (Atiles and Bohon 2003; Burton et al. 2013; Gouveia and Saenz 2000; Gozdziak and Martin 2005; Kandel and Parrado 2005; Leclere, Jensen, and Biddlecom 1994; Lichter et al. 2010, 2015; Lichter 2012; Marrow 2011; Parrado and Kandel 2008).

Rural communities also face challenges from rapid immigrant population growth, including racial tensions between newcomers and native-born whites and African Americans who may perceive immigrants, especially Latino immigrants, as economic threats (McClain et al. 2007). Also, rural new destination communities may face increased demand on local infrastructure and resources from rapid population growth (Crowley and Lichter 2009; Dondero and Muller 2012; Singer 2004). Many rural communities have, however, benefited from immigrant population growth because newcomers offset population loss and stave off economic stagnation or decline (Brown 2014; Donato et al. 2007; Johnson 2011, 2014; Lichter and Johnson 2006).

Comparisons of average county-level immigrant poverty rates for rural established immigrant destinations (i.e., those with a history of substantial immigrant populations), new immigrant destinations (i.e., recent high-growth immigrant populations), and nonimmigrant destinations (all other counties) are presented next. In 1990, there were 714,159 immigrants residing in nonmetropolitan counties in the United States, representing 1.8 percent of the total nonmetropolitan population. “Established immigrant destination counties” are those that were home to at least twice this overall nonmetropolitan percentage of immigrants in 1990 (3.6 percent). “New immigrant destination counties” were classified using two steps. First, all nonmetropolitan counties that grew by at least 200 immigrants between 1990 and 2009/2013 (N=903) were selected, which eliminated fast-growing counties that added only small numbers of immigrants. Second, counties that experienced above average nonmetropolitan immigrant population growth (greater than 285 percent) between 1990 and 2009/2013 were identified. This approach yielded 214 nonmetropolitan established destination counties, 361 nonmetropolitan new destination counties, and 1,401 other nonmetropolitan counties (“nonimmigrant destination counties”) (figure 7.6).

Figure 7.6 Nonmetropolitan established and new immigrant destinations.

Source: Author classification based on Census 1990 and American Community Survey 2009/2013.

Established destinations are home to about 35 percent of nonmetropolitan immigrants. The majority of the 214 nonmetropolitan established destinations are in Texas (86), California (14), New Mexico (14), Idaho (13), Washington (11), and Nevada (9). These are areas of long-term residence among mostly Mexican immigrants. Established destinations in Florida represent long-term Cuban populations, and established destinations in New England and northern New York represent mostly Canadian immigrants. With the exceptions of Texas and Florida and a handful of counties in Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Arkansas, the nonmetropolitan South had little experience with immigration before 1990. New destinations (N=361) are home to about 29 percent of nonmetropolitan immigrants and are disproportionately located in the South (figure 7.6). Many of these are in North Carolina (45), Georgia (43), Kentucky (21), Tennessee (19), Arkansas (17), Mississippi (16), and Virginia (16), but 25 Texas counties are also new destinations. Just 2 percent of nonmetropolitan midwestern counties are classified as established immigrant destinations (and nearly all are in Kansas), but 10 percent of nonmetropolitan midwestern counties are new immigrant destinations, mostly in Nebraska (12), Iowa (14), and Indiana (14).

The majority of nonmetropolitan counties in all regions are nonimmigrant destinations (N=1,401), including all nonmetropolitan counties in North Dakota, and nearly all in Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Many of these counties do have immigrant populations, but the populations are very small. Nevertheless, a substantial number of immigrants (612,880), representing 36 percent of nonmetropolitan immigrants, live in the 1,401 nonimmigrant destination counties—more than the number of immigrants in either nonmetropolitan established destinations (600,291) or new destinations (506,044).

Average immigrant poverty rates and the gap in poverty rates between immigrants and native-born residents vary significantly between nonmetropolitan established, new, and nonimmigrant destinations (table 7.3). Average poverty rates for both native- and foreign-born residents are lowest in nonimmigrant destinations and highest in new destinations. Nonmetropolitan established destinations have an average foreign-born poverty rate of 23.3 percent, compared to 29.0 percent in new destinations, and 21.0 percent in nonimmigrant destinations. The gap between the average native- and foreign-born poverty rates is also the largest in new destinations (10.3 percentage points). As explained earlier, poverty rates are higher among noncitizens. New destinations have a significantly higher average noncitizen poverty rate (33.9 percent) than both established (28.2 percent) and nonimmigrant (27.2 percent) destinations. However, large standard deviations for these poverty rates indicate that there is substantial variability in poverty rates among counties within each type of destination, with some counties having very low and other counties having very high poverty rates. This confirms that immigrant economic mobility has been highly segmented across the United States (Martin et al. 2006).

Table 7.3 Average Nonmetropolitan County Poverty Rates by Destination Type, 2009/2013

| |

Nonmetropolitan counties (N=1,477) (%) |

Established destinations (N=205) (%) |

New destinations (N=357) (%) |

Nonimmigrant destinations (N=915) (%) |

| Native-born |

17.5 (6.1) |

17.3 (6.4)b |

18.7 (6.2)a, c |

16.9 (5.9)b |

| Foreign-born |

23.2 (14.2) |

23.3 (11.2)b, c |

29.0 (14.4)a, c |

21.0 (14.0)a, b |

| Naturalized citizens |

14.4 (14.8) |

14.1 (10.3) |

16.1 (16.2)c |

13.6 (15.1)b |

| Noncitizens |

28.9 (19.5) |

28.2 (14.1)b |

33.9 (17.6)a, c |

27.2 (20.9)b |

| |

Nonmetropolitan counties (N=1,132) |

Established destinations (N=194) |

New destinations (N=331) |

Nonimmigrant destinations (N=607) |

| Children with native-born parents |

23.1 (9.6) |

22.3 (10.2)b |

24.7 (10.0)a, c |

22.5 (9.1)b |

| Children with at least one foreign-born parent |

31.4 (21.4) |

29.1 (16.6)b |

40.0 (20.6)a, c |

27.4 (21.8)b |

Source: American Community Survey 2009/2013.

Notes: Poverty rates represent the percentage of the population below 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Overall poverty rates (top section of the table) are calculated among counties with at least one hundred immigrants and not missing on poverty rates; child poverty rates (bottom section of the table) are calculated among counties with at least one hundred children living with immigrant parent(s).

a Denotes significant difference from established destinations at p<0.05.

b Denotes significant difference from new destinations at p<0.05.

c Denotes significant difference from nonimmigrant destinations at p<0.05.

Table 7.3 also displays average county-level poverty rates for children living in the United States with native-born versus foreign-born parents.9 In 2009/2013, 840,078 nonmetropolitan children (8.5 percent) lived with at least one immigrant parent. Of those, 286,977 (34.2 percent) were in poverty. The percentage of children living with immigrant parents and their poverty rates vary considerably across destination types. Nearly one-quarter of children in established destinations live with at least one foreign-born parent compared to 12.5 percent in new destinations and 6.1 percent in nonimmigrant destinations.

Average county poverty rates are higher among children of immigrants (the second generation) than among children of native-born parents in all three destination categories, but children of immigrants in new destinations are the most disadvantaged by far. In the average nonmetropolitan new destination, 40 percent of children of immigrants are in poverty. The poverty gap between children with native-born versus immigrant parents is also the largest in new destinations (15 percentage points). Nearly all of the highest poverty rates among children of immigrants in new destinations are in the South. In Greene County, Tennessee, for example, 86 percent of the 773 children with at least one immigrant parent are in poverty. In Coffee County, Georgia, of the 1,532 children of immigrants, 78 percent are in poverty, and all of the 134 children of immigrants in Clay County, North Carolina, are in poverty.

Child poverty is especially problematic because it places children on a disadvantaged path from the starting gate (Lichter et al. 2015) and influences later health outcomes, educational attainment, and transitions to productivity in adulthood (Clotfelter, Ladd, and Vigdor 2012; Duncan, Ziol-Guest, and Kalil 2010). Given now long-term declines in intergenerational socioeconomic mobility in the United States, the emergence of a more rigid class structure, and changing employment conditions that make it more difficult to lift a family out of poverty (McCall and Percheski 2010; Van Hook, Brown, and Kwenda 2004), the odds that poor children will also be poor adults are increasingly high (Borjas 2011). This is especially the case among children of Mexican immigrants. Although children of Mexican immigrants are more likely to live in two-parent families with a working male head than children of native-born parents, and living in a two-parent family is protective against poverty (Lichter and Landale 1995), children of Mexican immigrants still experience disproportionately high poverty rates (Lichter, Qian, and Crowley 2005).

There is some room for optimism as recent research provides evidence of intergenerational upward mobility (improvements in income and reductions in poverty) from the first to second generation (Alba, Kasinitz, and Waters 2011; Borjas 2006; Park and Myers 2010; Park, Myers, and Jimenez 2014). Research, however, also notes third-generation stagnation or decline (Tran and Valdez 2015), and progress appears to be proceeding unevenly, with some immigrants and their children achieving a version of the American dream in certain places as others face persistent poverty elsewhere (Martin et al. 2006). Unfortunately, no existing research disaggregates intergenerational mobility between metropolitan and nonmetropolitan immigrants, leaving questions about whether the new second generation born in rural areas will be able to merge into the economic mainstream similar to generations of past immigrants.

The human and social capital immigrants bring with them from their native countries heavily influenced economic well-being. It is important to understand whether immigrant poverty rates are higher in rural new destinations simply because of this negative selection. That is, is immigrant poverty higher in new destinations simply because immigrants in new destinations lack the education and English proficiency necessary to secure jobs with high enough wages to keep them out of poverty? Also, year of entry can influence poverty risk because employment is easier to maintain during strong economic periods than during recessions. Moreover, those with more time in the United States have had longer to adjust and adapt to U.S. customs and practices and may have less difficulty navigating employment and safety net systems than those who arrived more recently. Finally, as previously emphasized, rural immigration has historically been economically driven. Labor force demand, wages, and the need for low-skill versus high-skill workers vary across industries, and industry composition varies across destinations. Labor market differences across destination types may help us better understand differences in poverty rates.

In the average nonmetropolitan county, immigrant median income is $20,482, but immigrant median income is lower in new destinations ($19,566) than in established ($20,280) and nonimmigrant destinations ($20,884) (table 7.4). Yet, on average, immigrants to new destinations bring with them better human capital than those in established destinations. In the average established destination, 52.8 percent of immigrants lack a high school diploma (compared to 47.1 percent in the average new destination), and only 12 percent have a four-year college degree or more (compared to 13.4 percent in the average new destination). English speaking is also more prevalent in new versus established destinations. Immigrants in nonimmigrant destinations are much more educated and more likely to speak English than those in either established or new destinations. The number of immigrants with stronger human capital moving to nonimmigrant destinations may partly explain their lower poverty rates relative to their peers in new and established destinations. However, higher immigrant poverty rates in new compared to established destinations cannot be explained simply by lower educational attainment and difficulty speaking English among immigrants in new destinations, given that immigrants in new destinations are stronger on those markers than immigrants in established destinations.

Table 7.4 Average Characteristics of the Foreign-Born Population in Nonmetropolitan Counties by Destination Type, 2009/2013

| |

Nonmetropolitan counties (N=1,477) |

Established destinations (N=205) |

New destinations (N=357) |

Nonimmigrant destinations (N=915) |

| Median income (2013 constant dollars) |

20,482 (7,890) |

20,280 (6,685) |

19,566 (5,751) |

20,884 (8.783) |

| Percent age 25+ without high school diploma |

38.6 (20.8) |

52.8 (20.8) |

47.1 (17.8) |

32.1 (19.0) |

| Percent age 25+ with 4-year college degree or higher |

18.1 (14.6) |

12.0 (13.6) |

13.4 (10.4) |

21.4 (15.3) |

| Percent who speak language other than English at home |

74.4 (18.0) |

85.3 (15.1) |

83.3 (12.0) |

68.5 (17.9) |

| Percent age 5+ who speak English well or very well |

48.3 (13.8) |

47.4 (11.6) |

48.0 (12.5) |

48.6 (14.8) |

| Percent noncitizens |

62.3 (17.4) |

66.7 (15.0) |

72.7 (12.9) |

57.2 (17.3) |

| Year of entry to United States |

| Entered before 1990 (%) |

36.1 (16.6) |

42.2 (15.1) |

25.2 (11.2) |

39.1 (16.8) |

| Entered 1990–1999 (%) |

24.2 (12.4) |

25.2 (8.8) |

28.0 (11.5) |

22.5 (13.1) |

| Entered 2000–2009 (%) |

34.0 (15.2) |

28.3 (11.3) |

41.5 (13.9) |

32.3 (15.4) |

| Entered in 2010 or later (%) |

5.7 (7.8) |

4.4 (5.2) |

5.4 (7.2) |

6.1 (8.5) |

| Labor market characteristics |

| Percent unemployment rate (civilian population, age 16+) |

5.2 (1.9) |

5.0 (2.0) |

5.5 (1.9) |

5.2 (1.9) |

| County economic dependency |

| Farming (%) |

12.1 |

28.8 |

12.9 |

8.1 |

| Mining (%) |

5.8 |

11.7 |

2.5 |

5.8 |

| Manufacturing (%) |

33.0 |

8.8 |

44.8 |

33.8 |

| Federal/state government (%) |

12.3 |

20.0 |

7.8 |

12.3 |

| Services (%) |

6.2 |

7.8 |

5.9 |

6.0 |

| Nonspecialized (%) |

30.6 |

22.9 |

26.1 |

34.0 |

Source: American Community Survey 2009/2013.

Note: Among counties with at least one hundred foreign-born residents with no missing data on variables of interest.

Immigrants in new destinations do have a comparative disadvantage when it comes to period of entry. Immigrants in established and nonimmigrant destinations have been in the United States longer than those in new destinations, and a much larger percentage of immigrants in the average new destination (41.5 percent) entered the United States during the economically volatile 2000s. Moreover, the average percentage of immigrants who are not U.S. citizens is lower in both established destinations (66.7 percent) and nonimmigrant destinations (57.2 percent) than in new destinations (72.7 percent). As noted earlier, lack of citizenship reduces access to the critical safety net resources needed to help pull families out of poverty.

Finally, there are important labor market differences across the three types of destinations. The ACS does not provide detailed county-level employment information for immigrants, so table 7.4 presents the average county unemployment rates for the whole civilian population as well as the percentage of nonmetropolitan counties falling into each of the USDA Economic Research Service’s economic dependency types by destination.10 The average unemployment rate is higher in new destinations than in either established or nonimmigrant destinations. Agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and services are industries that employ large percentages of nonmetropolitan immigrants. However, wages, employment conditions, and job security vary tremendously across these industries and are not evenly distributed across the country. Table 7.4 also presents the percentage of nonmetropolitan counties falling into each of the USDA Economic Research Service’s economic dependency types by destination. Established destinations are the most dependent on farming; 28.8 percent of nonmetropolitan established destination counties are farming dependent. Immigrants employed in farming are at high risk of poverty due to low wages and mostly seasonal and unpredictable work schedules (Martin et al. 2006). However, a fifth of established destinations are dependent on state or federal government employment, somewhat buffering them from the risk of unemployment and poverty that often occur during economic downturns. New destinations are the most dependent on manufacturing; 44.8 percent of nonmetropolitan new destinations depend on manufacturing as their major source of employment, and fewer than 8 percent are reliant on federal or state government employment. Rural manufacturing was hit hard during the Great Recession (2007–2009), and low-skill immigrants experienced greater job loss and underemployment during the recession than the native born, which may have partially contributed to higher immigrant poverty rates in new destinations. There is some evidence, however, that among those with a high school diploma or more, immigrants experienced a stronger post-recession job recovery than did the native-born population (Enchautegui 2012), leaving room for optimism that rural immigrant poverty may decline as the economy strengthens.

CONCLUSION

The 1990s and 2000s were characterized by considerable immigrant population growth in rural United States. Although immigrants have traditionally been drawn to urban gateways, parts of rural U.S. have been home to a non-negligible share of immigrants throughout the past 170 years. Despite changes in the composition and distribution of the U.S. immigrant population, today’s immigrants face just as many, and perhaps more, challenges to successful incorporation into U.S. society as did prior immigrant generations. A combination of several political and economic forces contributed to the increase in rural immigration over the past twenty years, including immigration policy exemptions allowing farm operators to recruit foreign workers, U.S.–Mexico border militarization and increasing hostility toward immigrants in the U.S. Southwest, increased U.S. and global demand for processed foods and disposable products, and the restructuring of U.S. manufacturing.

The rural United States is now home to 1.7 million immigrants, and immigrants currently comprise a larger share of the rural population than at any time in the previous sixty years. Immigrants remain geographically concentrated in large cities, but the dispersion of Latin American–origin immigrants to rural areas with little or no previous experience with nonwhite immigrants has changed the face of the rural U.S. and prompted questions about the ability of these communities to absorb this new population and about the ability of the immigrants themselves to incorporate. Despite being more highly educated and English-proficient, immigrants in rural new destinations have lower average incomes and higher average poverty rates than those in rural established destinations. This is at least partly due to a greater presence of noncitizens and more recently arrived immigrants in new compared to established destinations, but it is also related to the mix of industries in different destinations and the resilience of those industries to economic downturns. Much of the progress rural immigrants made toward closing the poverty gap in the late 1990s and early 2000s halted or reversed during the Great Recession of the late 2000s (Crowley, Lichter, and Turner 2015). Current safety net policies restrict immigrant eligibility for programs that could help pull them out of poverty. These findings are consistent with those of Lichter et al. (2015), who note that even when they “play by the rules” (i.e., obtain education, learn English), structural conditions, including lower wages in rural new destinations and restrictions on safety nets, place immigrants in rural new destinations at especially high risk of poverty.

High poverty rates among children of immigrants are especially concerning because childhood poverty is likely to be a greater barrier to upward mobility now than in past generations (McCall and Percheski 2010; Van Hook et al. 2004). Rural immigrant poverty is often exacerbated by native-born youth out-migration, poor access to health services, and underfunded and poor-quality schools, all of which limit opportunities for upward mobility (Dondero and Muller 2012). Although children of immigrants represent just 8.5 percent of all nonmetropolitan children, they represent nearly 12 percent of those living in poverty. A staggering one-third of nonmetropolitan children of immigrants are in poverty, and in new destinations, the average poverty rate among children of immigrants is 40 percent, characterizing what Lichter et al. (2015) refer to as the “ghettoization of rural immigrants.” Yes, rural areas contain comparatively small numbers of immigrants today, but if current fertility trends continue, children of immigrants (especially Latinos) will represent a much larger percentage of rural residents in the decades to come. Therefore, high poverty rates among rural children of immigrants have important implications for the future of many rural areas, especially those in the South and West, where 70 percent of nonmetropolitan immigrants now live. Nearly one-quarter of all U.S. births today are to Latinos (J. Martin et al. 2013), and Latino childbearing is highest among the poorest and most disadvantaged immigrants (Lichter et al. 2012). Growth in the rural Latino population is now driven by fertility rather than continued immigration, which has leveled off (Lichter et al. 2012). Therefore, the effects of current immigration policies are most salient for the children and grandchildren of immigrants (i.e., the second and third generations), who will play a growing role in the future economies of many rural areas and in the United States at large.

The challenges of reducing rural immigrant poverty are considerable, but not insurmountable. Marriage and employment promotion, often cited as major antidotes to poverty, are likely to be less effective in reducing poverty among immigrants because most immigrants with children are already married and employed. Rather than unemployment, low wages and underemployment (part-time, seasonal work) seem to be the major drivers of immigrant poverty (Slack and Jensen 2007). Wages among immigrant farmworkers are especially low (Martin and Jackson-Smith 2013), despite evidence debunking large farm operators’ claims that low wages are necessary to maintain low food costs (Martin et al. 2006). Moreover, agricultural workers are largely excluded from laws that protect other workers, including the right to overtime pay. Most immigrants who are farmworkers work for large farm corporations rather than small family farms. Modifications to current U.S. guest worker programs to allow migrant workers to move freely between employers might be one way to diminish seasonal unemployment and favor employers who provide the best working conditions and compensation (Martin et al. 2006).

Of course, most rural immigrants are not farmworkers, and more diversified strategies are needed to reduce poverty among immigrants working in manufacturing and services. Some rural areas with large immigrant populations may benefit from investing in training and apprenticeship programs in industries and occupations primed for growth in rural areas, including green energy, telecommunications, and health care for the aging baby boomer population. These training programs are likely to be especially appealing to immigrants if they include concomitant training in English. Apprenticeship programs such as these would also benefit native-born rural residents who may not be interested in or have the resources to attend college.

It is clear that noncitizen immigrants drive high immigrant poverty rates, so the key to reducing immigrant poverty rates is reducing poverty rates among noncitizens. Policy proposals from divergent sides of the political spectrum range from rounding up and deporting all undocumented immigrants and their children, which has been shown to be a largely ineffective strategy (Martin et al. 2006), to providing a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants who are currently in the United States and can document employment. The path we go down will have major implications for whether the children of today’s rural immigrants—most of whom are native-born American citizens—will escape poverty and achieve upward mobility as previous generations of immigrants have done.

J. Celeste Lay

Until the early 1990s, Perry was similar in most ways to other small, Iowa towns. Founded in 1869 by Harvey Willis, Perry was a railroad and manufacturing town for most of its history. Its first meatpacking plant opened in 1920; in the 1960s and 1970s, jobs at the local Oscar Mayer plant were some of the most coveted in the community. Residents in Perry were long-timers; many had roots going back several generations, and in 1990, nearly everyone (99.2 percent) was white.1

Things began to change when Oscar Mayer sold the plant to Iowa Beef Packers in 1988. The “new breed” of meatpacking companies, taking advantage of right-to-work laws and new technology that made skilled butchers unnecessary, moved their operations to small towns across the Midwest and South. Predictably, they slashed wages and benefits and increased line speeds. When there were inevitable labor shortages, the plants began to recruit Latinos, first from U.S. cities and then from Mexico and parts of Central America (Warren 2007; Johnson-Webb 2002; Krissman 2000).

Between 1988 and 2000, Perry was transformed. In the 2000 Census, nearly one-quarter of Perry residents identified as Hispanic. The rate of immigration slowed slightly over the next decade; by 2010, Latinos made up 35 percent of Perry residents (see table 7.5).

Table 7.5 Population Characteristics of Perry, Iowa, 1990 and 2010

| |

1990 |

2010 |

| Populationa |

6,652 |

7,702 |

| Ethnic composition |

|

|

| % Non-Hispanic whitea |

99.2 |

61.1 |

| % Latinoa |

0.7 |

35.0 |

| % Foreign-born |

1.2 |

21.8b |

| Socioeconomic status |

|

|

| % Bachelor’s degree or higher |

13.4 |

10.8b |

| % Below poverty line |

11.5 |

15.1b |

| Median household income |

$21,999 |

$35,881b ($21,506 in 1990 dollars) |

| Per capita income |

$12,653 |

$16,885b ($10,120 in 1990 dollars) |

a Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Census 1990 and 2010.

b Source: American Community Survey Estimates, 2005–2009, U.S. Census Bureau.

Getting Settled

Such substantial demographic change, called “rapid ethnic diversification,” had enormous effects on the community (Grey 2006; Grey, Devlin, and Goldsmith 2009). As one would expect with any sudden increase in population, Perry experienced a housing shortage in the first several years after immigrants began to arrive. Male migrants came and went in Perry with regularity, as some would work only a short time and leave. Because the plant did not offer health insurance until one had worked for several weeks, and meatpacking is one of the most dangerous jobs in the country, the local hospital saw its uninsured costs rise exponentially.

By the mid- to late-1990s, turnover rates at the plant slowed, men brought their wives and children, and families began to put down roots in the community. Public schools had to increase their resources for the rapidly growing number of students who did not speak English. The strain on public services, however, was a short-term crisis (Congressional Budget Office 2007). Today, excepting first-generation immigrants, Latino residents in Perry were born in the United States and most speak English as their first (and often only) language.

Social and Economic Incorporation

Perry is somewhat poorer today than in 1990. The poverty rate was higher in Perry in 2010 than in 1990, but this was also true nationally. Perry’s 2010 poverty rate was identical to the U.S. rate. The median income stayed the same between 1990 and 2010 (as it did nationally), but Perry’s per capita income declined, indicating that a large portion of the population had extremely low incomes.

Even with low incomes, a job in the meatpacking plant offered immigrants several benefits. Not only were the jobs year-round and relatively stable, but many families appreciated small town life. They preferred the relatively quiet and peaceful communities to cities because of lower crime, better schools, and opportunities for social and economic mobility “precisely when similar opportunity [had] begun to stagnate, become saturated, or even decline in the traditional immigrant gateways” (Marrow 2011, 241; Donato et al. 2007).

Social stratification did not begin with immigration in Perry and other small towns. There had always been divisions along social, economic, and ethnic lines (Duncan 1999). Perry has always been a working class community, however, and Latino migrants do not hold a significantly lower status than the majority of white residents.

Still, interethnic relations were not always easy. In the early years, many Perry residents resented the changes at the plant and did not welcome the newcomers, but most residents no longer see Perry’s immigrants as “outsiders.” In most ways, immigrants have been incorporated into the community. Latino immigrants have opened businesses along the town’s main streets and have become more active in civic life through organizations such as Hispanics United for Perry. Interethnic dating is no longer an oddity at the local high school, and Latino and white residents come together not only in support of the local football team but also to grieve the loss of local men killed in the line of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan. Although most small towns watch their best and brightest move away for college and jobs, towns like Perry have a burgeoning number of hard-working young people who want to stay in or return to small towns to raise their families.

This pattern of initial suspicion followed by acceptance and incorporation is not unique to Perry, but it is certainly not the case that interethnic relations always go smoothly. Larger towns and cities often have higher levels of residential segregation and more economic stratification. As such, there is less interaction between existing residents and newcomers, and it is more difficult for low-wage immigrant workers to join the local economic mainstream. In these communities, immigrants remain on the outside, and incorporation is a longer, more difficult process. Larger cities may want to look at these small, insular communities as a model for successful transition.

NOTES

1. We use the terms immigrant and foreign-born interchangeably. The U.S. Census Bureau uses “foreign-born” to refer to anyone who is not a U.S. citizen at birth, including naturalized citizens, lawful permanent residents, temporary migrants (e.g., foreign students, workers on visas), humanitarian migrants (e.g., refugees), and undocumented migrants. Individuals born in Puerto Rico or a U.S. Island Area, as well as those born abroad of at least one U.S. citizen parent, are native born.

2. We use the term nonmetropolitan rather than rural because the trends described throughout the chapter are for counties outside the bounds of metropolitan areas, as defined by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), but include some urban populations. Metropolitan areas include counties containing an urban core of 50,000 or more population (or a central city) as well as neighboring counties that are highly integrated with the core county as measured by commuting patterns.

3. “Wetback” is a pejorative term originally applied to Mexicans who crossed the Rio Grande and then was extended to all Mexican laborers, including those who are legal residents.

4. The American Community Survey (ACS) took the place of the decennial census long-form, which was discontinued in 2010. The Census releases annual county population estimates from the ACS for counties with a population of 65,000+, three-year estimates for counties with a population of 20,000+, and five-year estimates for all counties. To be inclusive of all counties, the 2009/2013 five-year estimates were used, the most recently available estimates at the time of writing. The five-year estimates are the most reliable, especially for geographic areas with small populations. The trade-off of inclusivity and reliability is the inability to describe annual change.

5. Noncitizen does not necessarily imply undocumented status. In addition to undocumented residents, noncitizens may be lawful permanent residents, temporary migrants (such as foreign students or workers on visas), or humanitarian migrants (such as refugees).

6. County-level estimates for foreign-born poverty rates are unstable for counties with small foreign-born populations, so estimates were limited to those with at least 100 foreign-born residents.

7. Separate poverty rates are not available for undocumented immigrants. Undocumented immigrants are included in the calculations for noncitizen poverty rates, but there is no way to know what percentage of them is represented in these calculations. Given that undocumented immigrants have higher poverty rates than other immigrants, the poverty estimates for noncitizen immigrants are likely conservative (i.e., the rates would be higher if the Census had data on all undocumented immigrants).

8. There are some exceptions to this rule, including for refugees, asylees, battered spouses and children, and victims of severe human trafficking.

9. Children in two-parent households where both parents are native born and children living in one-parent households where that parent is native born are classified as living with native-born parents. Children in households where at least one parent is foreign born are classified as living in an immigrant-parent household.

10. True unemployment rates are much higher because discouraged workers who are no longer in the labor market are not included in unemployment counts. These data provide especially conservative estimates for counties with large shares of undocumented immigrants. Many undocumented immigrants are not included in unemployment counts because they do not qualify or are fearful of applying for unemployment insurance.

REFERENCES

Alba, Richard D., Philip Kasinitz, and Mary C. Waters. 2011. “The Kids Are (Mostly) Alright: Second-Generation Assimilation: Comments on Haller, Portes and Lynch.” Social Forces 89(3):763–73.

Atiles, Jorge H., and Stephanie A. Bohon. 2003. “Camas Calientes: Housing Adjustments and Barriers to Social and Economic Adaptation Among Georgia’s Rural Latinos.” Southern Rural Sociology 19(1):97–122.

Borjas, George J. 2006. “Making It in America: Social Mobility in the Immigrant Population.” Future of Children 16(2):55–71.

——. 2011. “Poverty and Program Participation Among Immigrant Children.” The Future of Children 21:247–66.

Brown, David L. 2014. “Rural Population Change in Social Context.” In Rural America in a Globalizing World: Problems and Prospects for the 2010s, ed. Conner Bailey, Leif Jensen, and Elizabeth Ransom, 299–310. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press.

Burton, Linda M., Daniel T. Lichter, Regina S. Baker, and John M. Eason. 2013. “Inequality, Family Processes and Health in the ‘New’ Rural America.” American Behavioral Scientist 57(8):1128–51.

Cance, Alexander E. 1912. “Immigrant Rural Communities.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 4:69–80.

Clotfelter, Charles T., Helen F. Ladd, and Jacob L. Vigdor. 2012. “New Destinations, New Trajectories? The Educational Progress of Hispanic Youth in North Carolina.” Child Development 83:1608–22.

Crowley, Martha, and Kim Ebert. 2014. “New Rural Immigrant Destinations: Research for the 2010s.” In Rural America in a Globalizing World: Problems and Prospects for the 2010s, ed. Conner Bailey, Leif Jensen, and Elizabeth Ransom, 401–18. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press.

Crowley, Martha, and Daniel T. Lichter. 2009. “Social Disorganization in New Latino Destinations?” Rural Sociology 74(4):573–604.

Crowley, Martha, Daniel T. Lichter, and Richard N. Turner. 2015. “Diverging Fortunes? Economic Well-Being of Latinos and African Americans in New Rural Destinations.” Social Science Research 51:77–92.

Dondero, Molly, and Chandra Muller. 2012. “School Stratification in New and Established Latino Destinations.” Social Forces 2:477–502.

Donato, Katherine M., Charles M. Tolbert II, Alfred Nucci, and Yukio Kawano. 2007. “Recent Immigrant Settlement in the Nonmetropolitan United States: Evidence from Internal Census Data.” Rural Sociology 72(4):537–59.

Duncan, Cynthia M. 1999. Worlds Apart: Why Poverty Persists in Rural America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Duncan, Greg J., Kathleen M. Ziol-Guest, and Ariel Kalil. 2010. “Early-Childhood Poverty and Adult Attainment, Behavior, and Health.” Child Development 81:306–25.

Durand, Jorge, Douglas S. Massey, and Fernando Charvet. 2000. “The Changing Geography of Mexican Immigration to the United States: 1910–1996.” Social Science Quarterly 81(1):1–15.

Effland, Anna B., and Marguerite A. Butler. 1997. “Fewer Immigrants Settle in Non-Metro Areas and Most Fare Less Well Than Metro Immigrants.” Rural Conditions and Trends 8(2):60–65.

Enchautegui, Maria E. 2012. Hit Hard but Bouncing Back: The Employment of Immigrants During the Great Recession and the Recovery. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Findeis, Jill L., and Leif Jensen. 1998. “Employment Opportunities in Rural Areas: Implications for Poverty in a Changing Policy Environment.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 80(5):1001–8.

Glazer, Nathan, and Daniel Patrick Moynihan. 1963. Beyond the Melting Pot. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gouveia, Lourdes, and Rogelio Saenz. 2000. “Global Forces and Latino Population Growth in the Midwest: A Regional and Subregional Analysis.” Great Plains Research 10:305–28.

Gozdziak, Elzbieta M., and Susan F. Martin, eds. 2005. Beyond the Gateway: Immigrants in a Changing America. New York, NY: Lexington Books.

Grey, Mark A. 2006. “State and Local Immigration Policy in Iowa.” In Immigration’s New Frontiers: Experiences from the Emerging Gateway States, ed. Greg Anrig Jr. and Tova Andrea Wang, 33–66. New York, NY: Century Foundation Press.

Grey, Mark A., Michele Devlin, and Aaron Goldsmith. 2009. Postville, U.S.A.: Surviving Diversity in Small-Town America. Boston, MA: GemmaMedia.

Hoynes, Hilary, Marianne Page, and Ann Huff Stevens. 2006. “Poverty in America: Trends and Explanations.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(1):47–68.

Johnson, Kenneth. 2011. “The Continuing Incidence of Natural Decrease in American Counties.” Rural Sociology 76(1):74–100.

——. 2014. “Demographic Trends in Nonmetropolitan America: 2000–2010.” In Rural America in a Globalizing World: Problems and Prospects for the 2010s, ed. Conner Bailey, Leif Jensen, and Elizabeth Ransom, 311–29. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press.

Johnson, Kenneth, and Daniel T. Lichter. 2008. Population Growth in New Hispanic Destinations. Policy Brief No. 8. Durham, NH: Carsey Institute.

Johnson-Webb, Karen D. 2002. “Employer Recruitment and Hispanic Labor Migration: North Carolina Urban Areas at the End of the Millennium.” The Professional Geographer 54:406–21.

Kandel, William, and John Cromartie. 2004. “New Patterns of Hispanic Settlement in Rural America.” USDA ERS Rural Development Research Report (RDRR-49). Washington, DC.

Kandel, William, and Emilio Parrado. 2005. “Restructuring of the U.S. Meat Processing Industry and New Hispanic Migrant Destinations.” Population and Development Review 31:447–71.

Krissman, Fred. 2000. “Immigrant Labor Recruitment: U.S. Agribusiness and Undocumented Migration from Mexico.” In Immigration Research for a New Century, ed. Nancy Foner, Ruben G. Rumbaut, and Steven J. Gold, 277–321. New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Leclere, Felicia, Leif Jensen, and Ann E. Biddlecom. 1994. “Health Care Utilization, Family Context, and Adaptation Among Immigrants to the United States.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35(4):370–84.

Lichter, Daniel T. 2012. “Immigration and the New Racial Diversity in Rural America.” Rural Sociology 77(1):3–35.

Lichter, Daniel T., and Martha Crowley. 2002. “Poverty in America: Beyond Welfare Reform.” Population Bulletin 57(2):3–36.

Lichter, Daniel T., and Leif Jensen. 2002. “Rural America in Transition: Poverty and Welfare at the Turn of the 21st Century.” In Rural Dimensions of Welfare Reform, ed. Bruce A. Weber, Greg J. Duncan, and Leslie E. Whitener, 77–110. Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Institute.

Lichter, Daniel T., and Kenneth M. Johnson. 2006. “Emerging Rural Settlement Patterns and the Geographic Redistribution of America’s New Immigrants.” Rural Sociology 71:109–31.

Lichter, Daniel T., Kenneth M. Johnson, Richard N. Turner, and Allison Churilla. 2012. “Hispanic Assimilation and Fertility in New U.S. Destinations.” International Migration Review 46:767–91.

Lichter, Daniel T., and Nancy S. Landale. 1995. “Parental Work, Family Structure, and Poverty Among Latino Children.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 57:346–54.

Lichter, Daniel T., Domenico Parisi, Michael C. Taquino, and Steven Michael Grice. 2010. “Residential Segregation in New Hispanic Destinations: Cities, Suburbs, and Rural Communities Compared.” Social Science Research 39:215–30.

Lichter, Daniel T., Zhenchao Qian, and Martha Crowley. 2005. “Child Poverty Among Racial Minorities and Immigrants: Explaining Trends and Differentials.” Social Science Quarterly 86(5):1037–59.

Lichter, Daniel T., Scott R. Sanders, and Kenneth M. Johnson. 2015. “Hispanics at the Starting Line: Poverty Among Newborn Infants in Established Gateways and New Destinations.” Social Forces 94(1):209–35.

Marrow, Helen. 2011. New Destination Dreaming: Immigration, Race, and Legal Status in the Rural American South. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Martin, Philip, Michael Fix, and J. Edward Taylor. 2006. The New Rural Poverty: Agriculture and Immigration in California. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Massey, Douglas S. 2008. New Faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, Douglas S., and Chiara Capoferro. 2008. “The Geographic Diversification of American Immigration.” In New Faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration, ed. Douglas S. Massey, 25–50. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, Douglas S., and Zai Liang. 1989. “The Long-Term Consequences of a Temporary Worker Program: The U.S. Bracero Experience.” Population Research and Policy Review 8(3):199–226.

McCall, Leslie, and Christine Percheski. 2010. “Income Inequality: New Trends and Research Directions.” Annual Review of Sociology 36:329–47.

McClain, Paula D., Monique L. Lyle, Niambi M. Carter, et al. 2007. “Black Americans and Latino Immigrants in a Southern City.” DuBois Review 4(1):97–117.

Park, Julie, and Dowell Myers. 2010. “Intergenerational Mobility in the Post-1965 Immigration Era: Estimates by an Immigrant Generation Cohort Method.” Demography 47(2):369–92.

Park, Julie, Dowell Myers, and Tomas R. Jimenez. 2014. “Intergenerational Mobility of the Mexican-Origin Population in California and Texas Relative to a Changing Regional Mainstream.” International Migration Review 48(2):442–81.

Parrado, Emilio A., and William Kandel. 2008. “New Hispanic Migrant Destinations: A Tale of Two Industries.” In New Faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration, ed. Douglas S. Massey, 99–123. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Singer, Audrey. 2004. The Rise of New Immigrant Gateways. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, Center for Urban and Metropolitan Policy.

Slack, Tim, and Leif Jensen. 2007. “Underemployment Across Immigrant Generations.” Social Science Research 36(4):1415–30.

Tran, Van C., and Nicol M. Valdez. 2015. “Second-Generation Decline or Advantage? Latino Assimilation in the Aftermath of the Great Recession.” International Migration Review (Fall):1–36.

Trump, Donald. 2015. “Presidential Campaign Announcement Speech.” New York, NY, June 15.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1990. 1990 Census of the Population and Housing, Summary File 3. Washington, DC. Accessed March 3, 2017.

——. 2000. 2000 Census of the Population and Housing, Summary File 3. Washington, DC. Accessed March 3, 2017.

——. 2015. American Community Survey, 2009–2013. Washington, DC. Accessed March 3, 2017.

Van Hook, Jennifer, Susan I. Brown, and Maxwell Ndigume Kwenda. 2004. “A Decomposition of Trends in Poverty Among Children of Immigrants.” Demography 41:649–70.

Warren, Wilson J. 2007. Tied to the Great Packing Machine: The Midwest and Meatpacking. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Zeitlin, Richard H. 1980. “White Eagles in the Woods: Polish Immigration to Rural Wisconsin, 1857–1900.” Polish Review 25(1):69–92.