Brian Thiede and Tim Slack

INTRODUCTION

Economic hardship is linked to changes in the availability and quality of jobs (Grusky, Western, and Wimer 2011). Most scholars agree that work does not offer oft-assumed promises of an above-poverty standard of living and upward mobility in the labor market, important tenets of the American Dream. Although the Great Recession has encouraged reflection about the plight of workers and the unemployed, empirical evidence shows that a large share of workers faced volatile labor market conditions long before this most recent economic crisis (Hacker 2008). Decades of economic restructuring have produced a new economy in which the odds of employment—particularly stable, well-paid employment with insurance and other benefits—are worse for rural workers (Kusmin 2014). Conditions in the postrecession era should be put into a broader context of social change. How and to what extent does this “new” economy represent a rupture from the past? What are the possible and probable paths forward?

This chapter provides general insights into the new rural economy and its historical antecedents. The chapter begins by tracing changes in the U.S. labor market over the last fifty years, with a special focus on the implications for poverty and economic well-being in rural areas. An original descriptive analysis is provided that moves beyond the question of poverty as officially defined by the U.S. government to assess the issue of underemployment in rural areas from 2002 to 2012. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the challenges and opportunities of this new economy for rural people and places moving forward.

SEPARATING THE OLD AND THE NEW

Discussions of things old and new must begin by marking the point of transition. In doing so, scholars often mistakenly imply that the “new” represents a break from a static, unchanging past. In fact, this is rarely the case, and the rural labor market dynamics discussed here are no exception. Rural economies and the work rural people pursue to make a living are never static; rather, they are subject to ongoing forces of social change. During the early years of the United States (as an independent nation-state), the vast majority of the population was rural, and most people found employment in agriculture and extractive activities. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, nearly 95 percent of the U.S. population resided in rural areas (Iceland 2014). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, the nation was transformed by the Industrial Revolution and urbanization. By the 1920 census, the U.S. population crossed the threshold from majority-rural to majority-urban for the first time (U.S. Census Bureau 2015). From this longer-term perspective, what now might be considered the “old” economy of the 1920s represented a dramatic departure from the century that preceded it.

Throughout the early twentieth century, industrialization fueled the migration of rural workers off of farms and into urban factories, a process facilitated by the increasing mechanization of agriculture. By 1950, nearly one out of three American workers was employed in manufacturing (Lee and Mather 2008). This rapid change, spanning from the end of World War II to the early 1970s, is often referred to as the Fordist period because of the prominent role of large-scale, standardized manufacturing. As the name suggests, many features of the economic structure during this period (e.g., assembly-line work in large factories or plants) were rooted in industrial innovations similar to Henry Ford’s automobile production systems. Many view this period as a golden age for working- and middle-class Americans. It was a time when U.S. manufacturing attained global dominance, the welfare state expanded to promote economic growth and the social safety net, organized labor held considerable sway over industry and politics, and declines in inequality and poverty corresponded with improving standards of living for common people.

In contrast, the years since the 1970s are cast as the post-Fordist era. Since then, new forces of social and economic changes—chief among them globalization—have taken hold and changed the number, type, and quality of jobs available to American workers. It is the economic circumstances of this final era that is characterized in this chapter as the “new” economy, and which is placed in comparative perspective with the “old” postwar Fordist period before it.

ECONOMIC CHANGE AND THE NEW ECONOMY

In the 1970s, the foundations of the postwar industrial economy began to shift, ushering in the age of globalization (Robinson 2001). In broad terms, shifts from nationally to globally oriented systems of production, and the entrance of new international competitors with very low production costs, brought changes in the composition of the U.S. labor market. Three interrelated trends are emblematic: (1) declining labor union membership and coverage, (2) deindustrialization and a corresponding increase in the size of the service sector, and (3) shifts toward nonstandard employment arrangements, such as subcontracting and franchising (Brady, Baker, and Finnigan 2013; Kalleberg, Reskin, and Hudson 2000; Morris and Western 1999; Weil 2014). In various ways, each of these changes eroded the power of labor versus corporate managers and investors, and undermined the quality of most workers’ jobs (Western and Rosenfeld 2011). Some scholars have suggested that the implication of these changes was a “great U-turn,” whereby prior trends of income equalization and broadly shared economic prosperity were reversed and replaced with growing income inequality and wealth concentration (Harrison and Bluestone 1988). Indeed, by some measures, inequality today is at its highest levels since before World War II (Saez 2013). However, it is important to emphasize that the process of economic restructuring was, and continues to be, an inherently spatial process. As the term globalization would suggest, changes have occurred in the distribution of sites of production and in the flows of labor and capital across countries around the world. Restructuring also has involved unevenly distributed changes across local labor markets and changing relations between rural and urban areas within the United States (Falk, Schulman, and Tickamyer 2003).

CHANGING INDUSTRIAL-OCCUPATIONAL COMPOSITION

Substantial changes in the composition of rural labor markets reflect the changing U.S. economy. The locus of rural employment first shifted out of agriculture and into manufacturing, then increasingly into the service sector. These changes reflect the restructuring of the agricultural sector and processes of globalization. They also underscore the relational nature of rural and urban labor markets within the United States, and between rural America and global markets (Lichter and Brown 2011). This period of globalization corresponded with changes in rural–urban dynamics, including rural-to-urban migration, urban-to-rural shifts in production activities, and reduced spatial and temporal barriers between remote rural areas and urban centers. Changes in the structure of rural labor markets also have had significant implications for the economic status of households (e.g., poverty) by affecting the likelihood of employment and the wages of those employed (Cotter 2002).

Discussions of economic restructuring during the twentieth century often focus on the globalization of capital and supply chains associated with the deindustrialization of high-income economies. These are critical processes to be sure. In rural America, however, long-term changes in the structure of the economy and labor markets should also be put in the context of a dramatic agricultural transition that played out across the entire twentieth century. Although U.S. agriculture is deeply embedded in world markets and was therefore shaped by the forces of post-1970s globalization as well, significant restructuring in this sector can be traced back decades before that. The net result is that the share of rural workers employed on farms or working as unpaid laborers on family farms has declined to just slightly more than a rounding error over the past five to six decades.

Lobao and Meyer (2001) show that the agricultural sector has become increasingly consolidated, as indicated by declining shares of workers in the agricultural sector, reductions in the number of farms, and increasing acreage per farm. For example, from 1940 to 1995, the farm population (as a percentage of the total population) declined from 23.1 percent to 1.8 percent (Lobao and Meyer 2001). As well, on-farm work was decreasingly likely to fully support households: by the end of the 1990s, upwards of 90 percent of household income among farmers came from nonfarm sources (Lobao and Meyer 2001; Sommer et al. 1998). Shifts away from an agricultural labor market also adversely affected the many businesses that supported the agricultural economy (Lobao and Meyer 2001).

The shift in rural labor away from farms initially corresponded with an increase in rural manufacturing (Albrecht and Albrecht 2000). Contrary to popular belief, manufacturing employed a larger share of workers in rural than urban areas as early as 1970 (Barkley and Hinschberger 1992). Rural manufacturing has been disproportionately, but not exclusively, centered on natural resources and agriculture. For instance, traditional types of rural manufacturing include those focused on food and fuel; textiles and leather; and furniture, lumber, and wood (Fuguitt, Brown, and Beale 1989; Henderson 2012). In 1980, 18 percent of rural workers employed in manufacturing were in the textile and apparel sector, compared to 7.9 percent of urban workers; likewise, 11.9 percent of rural manufacturing workers had positions in the furniture, lumber, and wood sector, versus 3.7 percent in urban areas. The shift toward rural manufacturing continued through the next two decades (Fuguitt et al. 1989). By the 2000 census, 17 percent of rural workers were employed in manufacturing, 3 percentage points higher than the 14 percent among urban workers (Vias 2012).

Shifts toward manufacturing were in part driven by technological changes. New production, communications, and transportation technologies facilitated shifts in manufacturing away from traditional urban industrial centers and into rural (and suburban) areas. In many cases, the driver of industrial decentralization was not the technology itself but labor costs, which were the most variable input due to growing global competition. The places that saw such increases in manufacturing were often both rural and located away from the urban cores of the Northeast and Midwest (Fuguitt, Brown, and Beale 1989). These emerging manufacturing sites were often in regions (e.g., the South) where antagonism toward labor unions and labor protections, low wages, and other factors associated with low labor costs made these places attractive (Eckes 2005).

The implications of the changing nature of U.S. manufacturing for labor were ambiguous. The increase in manufacturing jobs arguably mollified the adverse effects of the agricultural transition in many rural labor markets. The shift toward rural (and southern) manufacturing, however, can also be viewed as an integral step toward the declining power of workers’ unions and labor in the United States more generally. Relocation to these areas was part of a broader trend toward low-cost (i.e., low-wage) and nonunionized manufacturing (Eckes 2005; Falk and Lyson 1988; Holmes 2013). A considerable share of the manufacturing that emerged in rural areas in the 1970s involved low-skilled production such as textile and apparel production, which was (and still is) more vulnerable to global competition than high-skilled processes such as fuel and chemical production (Henderson 2012; Lyson and Tolbert 1996). As a result, the initial benefits of rural manufacturing were somewhat eroded over time (Bascom 2000). Indeed, Vias (2000, 278) argues that the relatively cheap, low-skilled labor that provided rural areas with their initial advantage relative to urban areas in the early stages of industrial decentralization eventually constituted a source of disadvantage. That is, as a more global market emerged, low-skilled manufacturing eventually shifted to sites with even lower production costs, undercutting low-cost rural workers in the United States in what some have characterized as a “race to the bottom” (Tonelson 2002).

From the 1970s, when the share of rural workers in manufacturing surpassed that of urban workers, to the year 2000, service sector employment in rural areas increased dramatically. By 2000, the service sector was home to at least two-thirds of all jobs in rural labor markets (Gibbs, Kusmin, and Cromartie 2005). In many cases, these shifts corresponded with more women participating in the labor force and declining employment among men (Burton, Lichter, Baker, and Eason 2013). Evidence suggests that rural service jobs are disproportionately low-skilled and low-quality positions. In 2000, 42.2 percent of the nonmetropolitan workforce was employed in a low-skill job, more than 8 percentage points higher than the 34 percent in metropolitan labor markets (Gibbs et al. 2005).

This figure is but one indicator that the debate about shifts from “good jobs” to “bad jobs”—which has largely been an aspatial conversation—is particularly relevant to rural labor markets. Prior research shows that rural workers are more likely to find employment in nonstandard positions than are their urban counterparts (McLaughlin and Coleman-Jensen 2008). Kalleberg and colleagues (2000) define such positions as those meeting at least one of four criteria: (1) a lack of a clearly defined (or any) employer; (2) a weak attachment between workers and their de jure employer; (3) an employer who does not control how workers do their job; and (4) workers who cannot assume continuity of employment. Although their research documents some exceptions to the link between nonstandard work and bad jobs, defined according to low pay and absent benefits, it largely supports the conclusion that increases in nonstandard work have a negative effect on workers’ economic status. Therefore, the disproportionate share of the rural workforce in nonstandard employment is another marker of the relative disadvantages that rural workers face in the new economy.

Arguably the most salient characteristic of the new, post-Fordist economy is the declining likelihood that families can attain a stable, above-poverty standard of living through the work of a single member (Slack 2010). Insecure, low-paying work and related spells of unemployment are increasingly common for rural workers. Although a nontrivial share of rural families is in poverty despite having one or more members employed (Slack 2010), such job disruptions also put those who are above the poverty line at risk of falling below it and increase the degree of hardship faced by already-poor families. In contrast, a small and perhaps shrinking group of well-educated workers maintain access to the remaining good jobs, and such bifurcation represents one of the central drivers of the growing inequality after the U-turn.

DIVERSITY IN THE NEW ECONOMY

A clear periodization of rural labor markets in the United States can be seen over the past half-century or more. That is, a transition out of agriculture and into manufacturing during the early phases of globalization was followed by a subsequent shift toward the service sector along with increases in nonstandard employment within industrial groups. Rural America is also characterized by diversity across space, reflecting patterns of uneven development over time. Rural America includes some of the most socially and economically marginal regions of the country (McGranahan 2003). To underline the challenges of constructing a single narrative of change in rural America over time, some examples of exceptions to the periodization just described are provided. Even these exceptional cases, however, support many common claims about rural disadvantage.

For one, changes in the global food system have been associated with the emergence of new economic centers in rural areas centered on food processing and meatpacking facilities (Broadway 2007; Kandel and Parrado 2005). In contrast to the decline in agricultural labor across rural America as a whole, the places where such food processing facilities have emerged have seen renewed links between labor markets and agricultural activities, and growth in food-related manufacturing. A substantial number of these facilities are located in small towns in the Midwest and Southeast where the construction of a single processing plant can represent a huge boon to the local economy (Broadway 2007). Workers in these plants are disproportionately of Hispanic origin, and thus they also represent major drivers of demographic change (Kandel and Parrado 2005). These boomtowns are unique economically and in terms of their rapidly increasing racial and ethnic diversity. Of course, many characteristics of rural food processing jobs are consistent with the larger narrative of work in the new economy: limited or nonexistent collective bargaining, weak worker protections (e.g., against occupational hazards), low pay, and variable hours. Some suggest that rural food processing constitutes the quintessential bad job (Broadway 2007).

Another example of diversity in the new economy is the oil and natural gas industry. This sector was transformed in the past decade through technological advances, namely hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) processes, which facilitate extraction of previously inaccessible resources. Rural labor markets located near these resource deposits have seen a large uptick in employment, both in oil and gas services directly and in the many goods- and service-providing establishments that support these activities. Between 2001 and 2010, employment in rural counties with significant oil and gas extraction activity increased by more than 5 percent, which stands in sharp contrast to the 2 percent decline in employment across other rural counties (Kusmin 2014). Similar trends persisted through 2013, with employment growth in extraction-oriented rural counties outpacing other rural counties by 2 percent (Kusmin 2014). Of course, rapid increases in employment driven by the growth of a single sector also create vulnerabilities. Recent data do not yet capture the full implications of a subsequent bust of the U.S. natural gas market, but good news is unlikely. As such, this case also underlines the boom-and-bust nature of resource-dependent economies—a salient problem in many rural areas (Freudenburg 1992).

Although the changes in oil- and gas-producing rural counties are unique vis-à-vis other places, this example also points to an important source of continuity within many rural labor markets: homogeneity and dependence. Although considerable diversity exists in labor markets and economic structures across rural America as a whole, many rural places are characterized by dependence on a limited set of, or even single, industries. Rural counties represent very large majorities of U.S. counties classified as farming-dependent (92 percent), mining-dependent (88 percent), manufacturing-dependent (65 percent), and federal and state government-dependent (55 percent) (U.S. Economic Research Service as cited in Slack 2014). The lack of industrial diversity reflects several disincentives for firms considering locating in rural areas, including geographic (e.g., spatial isolation), demographic (e.g., low population density), and social (e.g., low educational attainment) issues. Rural markets are more vulnerable to booms and busts (e.g., commodity and food price changes), provide few opportunities for laid-off workers or workers with skills mismatched with the dominant industry, and may be skewed by narrowly defined community development policies (Freudenberg 1992; Hamrick 2001; Joshi et al. 2000; Markhusen 1980). Rural residents often are motivated to turn to the informal sector as a livelihood strategy due to the lack of industrial diversity (Slack and Jensen 2010).

ECONOMIC RESTRUCTURING AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE

Discussions of work and poverty in rural areas face an underlying question of whether rural economic disadvantages reflect the unique structural conditions of rural economies and labor markets or systematic differences in population characteristics (Weber et al. 2005). This debate cannot be resolved here. The interaction between structural and demographic change arguably makes it unresolvable. However, three demographic conditions are integrally linked to the emergence and future trajectory of the new rural economy.

INCREASING RACIAL AND ETHNIC DIVERSITY

The racial and ethnic composition of the rural labor force has always been more diverse than commonly portrayed (Jensen and Tienda 1989), yet recent changes have ushered in a new era of diversity, and with it the potential for both tension and socioeconomic change (Lichter 2012). Here, the most salient trend is the increasing Hispanic share of the rural population, which has coincided with the emergence of new immigrant destinations across the country (Lichter and Johnson 2009). In the rural economy, these changes in part reflect the new geography of low-skill, low-paying work where Hispanic-origin immigrant workers often find employment (Kandel and Parrado 2005). The relative youth and high fertility of many Hispanic populations means that they will constitute a larger and growing share of the labor force into the future (Johnson and Lichter 2008). In many cases, these changes will offset trends toward population loss and aging. The extent to which such effects translate into sustainable community development will hinge on whether and how new Hispanic populations integrate into rural communities socially and in terms of human capital characteristics (Stamps and Bohon 2006).

EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

Questions about education are not limited to the emerging Hispanic population in rural America. Rural disadvantages in education and other dimensions of workers’ skillsets have been characteristic of the old and new economies, but skills gaps are an increasingly salient axis of rural–urban inequality in the new economy (Jensen and McLaughlin 1995). Not only are the remaining good jobs skewed toward high-skilled workers, but these jobs are also disproportionately located in urban areas, albeit with some “rural spillover” (McGranahan 2003). This incentivizes continued, if not deepening, rural-to-urban migration among higher-skilled (often young) rural workers. This process, called “brain drain,” has the potential to reinforce rural economic disadvantage into the future by, for example, shaping firms’ location decisions (Carr and Kefalas 2009; Domina 2006).

AGING

In addition to the out-migration of high-skilled workers in particular, many rural areas have experienced substantial net out-migration of young adults in general. Given that many of these migrants are of reproductive age, this yields lower fertility rates, natural population decrease, and population aging in many rural areas (Johnson 2011). In such cases, population aging is typically associated with economic decline, presumably as a result of both declining demand for goods and services and declines in the size and skill of the labor force. The population aging of many rural communities will almost certainly continue into the future as a result of the demographic momentum inherent in their age structures, which poses unique and largely unprecedented challenges for rural employment and rural economies (Slack and Rizzuto 2013).

That said, many rural areas have also experienced population aging from disproportionate in-migration of older adults, driven by the emergence of rural retirement destinations (Brown and Glasgow 2008). In these cases, population aging often is associated with an uptick in employment opportunities, some of which may include relatively high-skill and high-quality health care jobs.

RURAL EMPLOYMENT HARDSHIP IN THE EARLY 2000S IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

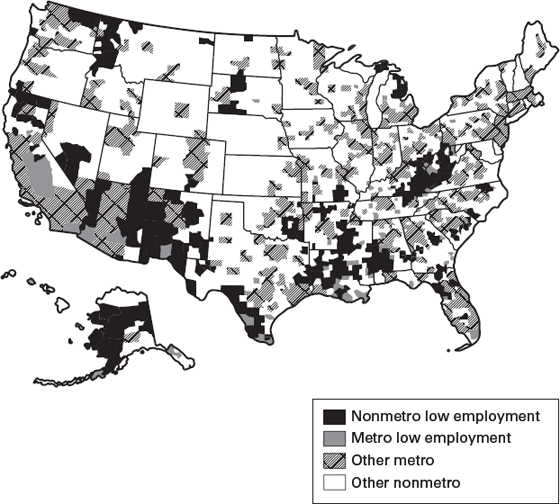

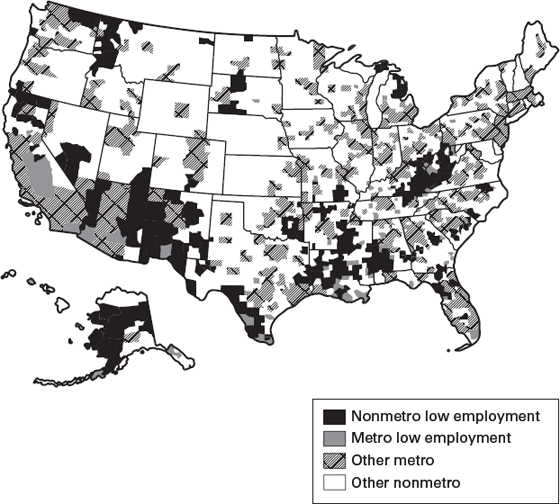

This section describes contemporary data that underscores the challenges faced by rural workers in the new economy. Given the strong links between employment and poverty in the United States, it follows that those who are out of work or living in a labor market where large shares of the working-age population are not employed will experience an increased likelihood of economic hardship. Data from the USDA’s Economic Research Service show that “low employment” counties—places where more than one-third of the working-age population is not employed—are disproportionately located in rural areas.1 The rural–urban comparison in this regard is stark: 86 percent of the counties that fit this definition are rural. Figure 9.1 provides a map of these places. Areas characterized by especially low employment are clustered in the Lower Mississippi Delta, the Black Belt, Central Appalachia, Native American reservations, and along the U.S.–Mexico border. Of course, the high level of economic distress in these regions is not solely a function of the new economy. In many cases, it is also the result of old and long-standing political economies of subordination and oppression in plantation agriculture, coal mining, and the federal reservation system—systems often undergirded by racist ideologies (Snipp 1996).

Figure 9.1 Low-employment counties, 2000.

Source: Economic Research Service, County Policy Types, USDA.

Note: Low-employment counties are those where less than 65 percent of residents 21 to 64 years old were employed in 2000.

Employment typically represents a necessary condition for escaping economic hardship among the poor, but it should not be mistaken as a sufficient condition for doing so. In what follows, an original descriptive analysis is provided that compares employment hardship among rural and urban workers from 2002 to 2012, drawing on data from the country’s most comprehensive annual national labor force survey, the March Current Population Survey (CPS). Linked annual data files from the March CPS were analyzed over this period to examine the employment circumstances of individuals aged eighteen to sixty-four years (i.e., those of working age).2 This approach extends analysis presented in Slack (2014) by carrying the record forward through the Great Recession and the very slow economic recovery that followed.

The focus of this volume is on poverty, but the official poverty measure used by the U.S. federal government has well-documented limitations (Citro and Michel 1995). Due to this chapter’s focus on labor markets, the analysis pivots from the consideration of economic hardship as measured by poverty (i.e., having a very low income) to examine underemployment, which captures broader forms of disadvantage. The concept of underemployment encourages us to think about different types of hardship that workers face as they endeavor to make a living in the labor market. Although measures of both poverty and underemployment capture ways people are struggling economically, they are not synonymous. Not only are different types of information used to develop each measure, but the populations of people assessed by each differs as well. Poverty is determined for nearly all members of the civilian population, whereas underemployment focuses on adults in the labor force (i.e., those of working-age who are either employed or actively looking for work).3 Therefore, it is possible to be underemployed but not be a member of a poor family or to be a member of a poor family but not be underemployed. The measurement of underemployment is detailed further in the following discussion, but the larger point is simply that it is necessary to think about the multidimensional types of hardship workers face in the American labor market.

Using the Labor Utilization Framework (LUF) developed by Clogg and Sullivan (Clogg 1979; Clogg and Sullivan 1983; Sullivan 1978), the operational states of underemployment examined here are:

Discouraged workers: individuals who would like to be employed but are currently not working and did not look for work in the past four weeks due to discouragement with their job prospects (official measures do not count these workers as “in the labor force” because they are neither employed nor looking for work);

Unemployed workers: consistent with the official definition, individuals who are not employed but (a) have looked for work during the previous four weeks, or (b) are currently on layoff but expect to be called back to work;

Low-hour workers (or involuntary part-time): consistent with the official definition of those who are working ‘‘part-time for economic reasons’’ (i.e., those employed fewer than thirty-five hours per week only because they cannot find full-time employment); and

Low-income workers: includes full-time workers (i.e., those employed thirty-five or more hours per week) whose average weekly earnings in the previous year were less than 125 percent of the individual poverty threshold.

All other workers are defined as adequately employed, and those who are not employed and do not indicate a desire to be so are defined as not in the labor force. The latter group is not included in our analysis.

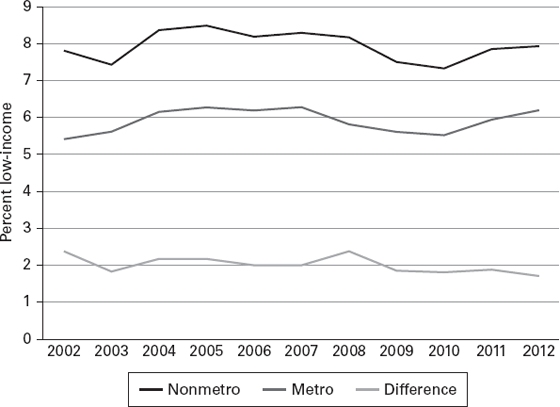

Figure 9.2 shows the percentage of workers who are underemployed (cumulatively by any type) from 2002 to 2012 in rural and urban areas, and the difference between the two (i.e., rural underemployment minus urban underemployment). Several important stories emerge from these data. The first is the markedly negative effect that the Great Recession, spanning December 2007 to June 2009, wrought on working people. In 2007, underemployment stood at 14.9 percent of the labor force nationally. In the subsequent three years, underemployment climbed to 15.5 percent in 2008, 21.9 percent in 2009, and ultimately topped out at 23.3 percent in 2010 before a degree of recovery began to take hold. In other words, by the end of the first decades of the 2000s, nearly one-quarter of U.S. workers found themselves underemployed, a truly staggering statistic.

Figure 9.2 Percent underemployed, by residence, 2002–2012.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, March Current Population Surveys, 2002–2012.

The circumstances of U.S. workers continued to deteriorate after the official end of the Great Recession in 2009. Many economic indicators, including underemployment and poverty, are lagging in nature. That is, even after the economy starts growing again at an aggregate level following a downturn, the economic circumstances of average people continue to deteriorate for some time before they begin to realize the benefits of recovery.

The other story these data tell is of the persistent labor market disadvantages faced by rural workers relative to their urban counterparts. Even though trends in underemployment rates have run in parallel in rural and urban areas over the ten-year period, rural workers have been subject to higher levels of underemployment in every single year examined. More specifically, between 2002 and 2012 rural workers faced an average underemployment rate of 20.4 percent versus 17.6 percent in urban areas. And in 2010, in the wake of the Great Recession, rural and urban underemployment stood at 25.0 percent and 23.0 percent, respectively. Again, these are staggering statistics when one considers the links between the status of workers and the economic well-being of the families that depend on them. The rural disadvantage observed here is not new to the 2000s; it is a trend that dates back as long as data have been available for this type of analysis (Slack and Jensen 2002).

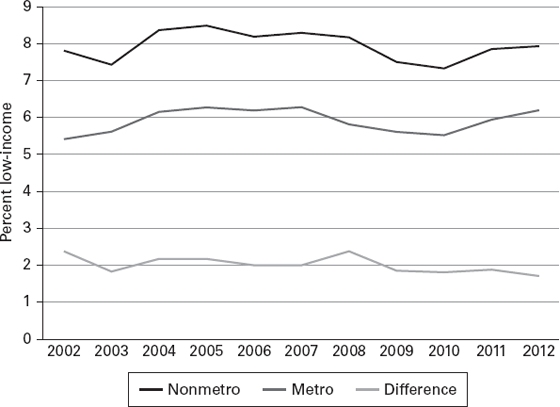

If underemployment by type is unpacked over this period, the data show that rural workers face higher rates of underemployment by low income (7.9 percent versus 5.9 percent in urban areas), and to a lesser degree by unemployment (7.0 percent versus 6.7 percent in urban areas) and low hours (4.5 percent versus 4.0 percent in urban areas). The only type of underemployment that remains at an equal level across residential areas over the ten-year period is discouragement (0.9 percent in both contexts). Examining trend data by year shows that unemployment and low-hours work started the period higher in rural areas, but the Great Recession brought about convergence in these measures between rural and urban areas as unemployment and involuntary part-time work rose in urban contexts toward rural levels. However, as illustrated in figure 9.3, the economic crisis only led to convergence in unemployment and low-hours work: low-income work remained a defining feature of the rural labor market throughout the period. At a decade-long average of 7.9 percent, low income stood as the single largest contributor to underemployment in rural settings (unemployment was the primary culprit in urban areas), averaging 2.0 percent higher than was the case in urban contexts across the period. This is an especially notable point for the purposes of this volume because it suggests that a disproportionate share of rural workers face economic hardship despite substantial labor market attachment. The implication is that the new rural economy leaves many behind, even many of those fully participating in it.

Figure 9.3 Percent of workers considered underemployed due to low income, by residence, 2002–2012.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, March Current Population Surveys, 2002–2012.

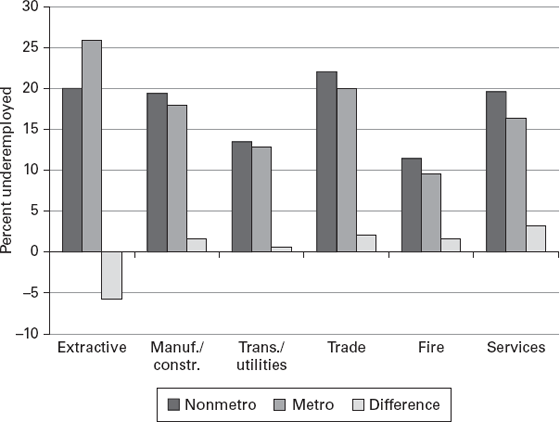

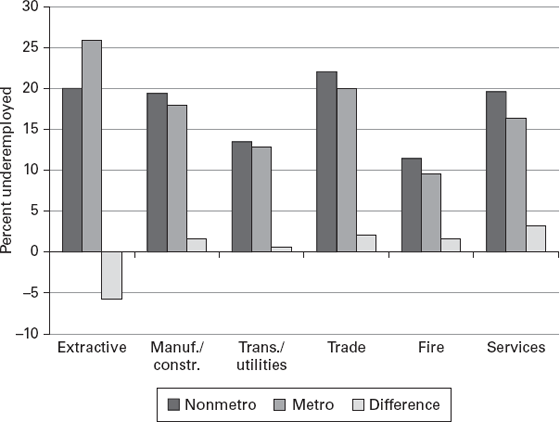

Figure 9.4 presents data on underemployment across major industrial sectors pooled for the ten years spanning 2002 to 2012. These data tell an important story about employment hardship in old and new economic sectors, and it is a story with significant implications for economic well-being across the rural–urban divide. Additional analysis from the CPS not shown here indicate that the two industrial sectors that claim a greater share of the labor force in rural as compared to urban areas are manufacturing/construction (24.2 percent rural versus 18.2 percent urban) and extraction (5.5 percent rural versus 1.2 percent urban). Extractive industries include mining, agriculture, forestry, and fishing, sectors well known for high and persistent underemployment (Slack and Jensen 2004). Moreover, given the earlier discussion about shifts away from agricultural and extractive employment and the subsequent process of deindustrialization, this labor force balance suggests a precarious position for many rural workers. That is, rural labor markets are arguably over-leveraged on the old economy. The dominance of services in the new economy is also readily evident in these data as the sector claims the largest total share of workers in both rural and urban contexts (43.8 percent and 49.3 percent, respectively). As noted earlier in the chapter, however, there are substantial differences in the quality of service jobs between rural and urban areas. As one example, Gibbs and colleagues (2005) show that between 1980 and 2000 the share of low-skilled service jobs was between 4.4 and 5.6 percentage points greater in rural than in urban areas. What figure 9.4 makes abundantly clear is that underemployment impacts rural workers to a greater degree than their urban counterparts across every major industrial sector except the extractive sector. Note that extraction represents a very small segment of the urban labor market (only about 1 percent), underscoring the magnitude of the rural disadvantage.

Figure 9.4 Percent underemployed by industrial sector, by residence, 2002–2012.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, March Current Population Surveys, 2002–2012.

Finally, table 9.1 presents data pooled across the period spanning 2002 to 2012 showing underemployment by residence for select worker characteristics. The table reveals well-known disadvantages in the modern labor market for younger, female, nonwhite, noncitizen, nonmarried, less educated, and/or nonunion workers. But what is especially notable is that underemployment is more pronounced for rural residents across every single group characteristic. The lone exception to this is labor union membership, which provides significant protection against underemployment in both rural and urban contexts alike. This final point provides reason for concern for American workers given trends toward deunionization in the new labor market and renewed antiunion sentiment in the political sphere (i.e., more states instituting so-called Right to Work laws and engaging in legal efforts to curb the influence of public sector unions). It also offers a point of optimism. Organized labor provided a tried-and-true mechanism for advancing the collective interests of working people in the old industrial economy, and it is still clearly linked to economic well-being in the new economy as well.

Table 9.1 Percent Underemployed by Residence by Select Characteristics, 2002–2012

| |

Rural (%) |

Urban (%) |

Difference (%) |

| Total |

20.2 |

17.5 |

2.7 |

| Age |

| 18–24 |

38.7 |

34.6 |

4.1 |

| 25–34 |

21.0 |

17.8 |

3.2 |

| 35–44 |

16.8 |

14.1 |

2.7 |

| 45–54 |

15.4 |

13.4 |

2.0 |

| 55–64 |

16.3 |

13.6 |

2.7 |

| Gender |

| Male |

18.8 |

17.0 |

1.8 |

| Female |

21.8 |

18.1 |

3.7 |

| Race/ethnicity |

| White |

18.3 |

14.2 |

4.1 |

| Black |

32.0 |

24.8 |

7.2 |

| Hispanic |

27.4 |

25.9 |

1.5 |

| Other |

27.0 |

17.0 |

10.0 |

| Nativity |

| Native |

20.0 |

16.2 |

3.8 |

| Second generation |

20.6 |

18.8 |

1.8 |

| Foreign-born, citizen |

19.9 |

15.6 |

4.3 |

| Foreign-born, noncitizen |

27.7 |

26.9 |

0.8 |

| Marital status |

| Married |

14.1 |

12.0 |

2.1 |

| Never married |

34.1 |

27.1 |

7.0 |

| Divorced/separated |

23.8 |

18.5 |

5.3 |

| Widowed |

23.8 |

19.3 |

4.5 |

| Education |

| Less than high school |

36.8 |

36.1 |

0.7 |

| High school |

22.7 |

22.0 |

0.7 |

| Some college |

20.5 |

18.5 |

2.0 |

| College degree or more |

10.7 |

9.4 |

1.3 |

| Labor union |

| Union |

4.9 |

5.1 |

−0.2 |

| Nonunion |

20.5 |

17.8 |

2.7 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, March Current Population Surveys, 2002–2012.

CONCLUSION

This chapter has traced the broad contours of change in the rural economy since the mid-twentieth century. The emergence of today’s new rural economy occurred within a longer-term process of agricultural restructuring that undermined the once-central role of agriculture in the rural labor market and supported the process of urbanization, processes which profoundly changed the size and composition of the rural labor force. In the wake of these changes, manufacturing and, later, service sector jobs have grown in importance throughout rural America, a trend consistent with the restructuring of the U.S. economy more broadly. Despite these and other similarities (e.g., growing racial and ethnic diversity), the new rural economy continues to produce conditions that disadvantage rural workers relative to their urban counterparts. This is made evident by the higher rates of underemployment consistently faced by rural workers across time and sector of employment.

What does all of this suggest going forward in the twenty-first century? One implication is that employment—whether in rural or urban environs—should not be assumed to be a sufficient condition for escaping poverty. Indeed, the link between work and poverty has been uniquely weak in rural relative to urban areas. From a policy perspective, this underscores the need to invest in “work support” programs that help to subsidize and reward the work efforts of those whose labor is met with inadequate returns. Examples include expanding the federal and state Earned Income Tax Credit program, raising the federal minimum wage and pegging it to inflation, devising programs aimed at offsetting work opportunity costs (e.g., child care and transportation subsidies), and expanding health care access to those unable to gain access through their workplaces via efforts like the Affordable Care Act. Although a point of great political contention in America, poverty rates are higher in the United States than in other similarly developed nations around the world not because their workers have higher earnings but because the governments of other nations redistribute far more of their national income for social welfare programs aimed at ameliorating economic inequality (Smeeding 2006).

Although much of the discussion in this chapter has been comparative, things “rural” and “urban” are always inextricably linked and interdependent on one another, never isolated. As Lichter and Brown (2011, 584) noted in a review, “Boundaries may divide people, but they also bring people together in intense patterns of social and economic interaction…. It is more difficult than ever to discuss social change in rural (or urban) America without acknowledging the other.” At a macro level, the implication moving forward is that the seeming challenges of work in the new rural economy cannot be addressed in isolation from broader dynamics in the urban and global economies. And at a micro level, this means that workers and their families are increasingly embedded in a rapidly changing, interconnected, and volatile economic reality that poses significant and growing challenges to escaping poverty, and achieving and sustaining a decent standard of living. In the end, these are fundamental challenges to the ideas that underlie the American Dream.

Jill Ann Harrison

Work provides the backdrop against which entire communities and the people within them thrive. Friedland and Robertson (1990, 25) eloquently captured the significance of work when they stated that “work provides identities as much as it provides bread for the table; participation in commodity and labor markets is as much an expression of who you are as what you want.” Therefore, changes in economic structures have implications that go far beyond the pocketbook. Working with shrimp fishers in a rural southeastern Louisiana bayou town I call Bayou Crevette provided insight into the ways workers respond when traditional ways of life are disrupted by globalization and occupational decline.

Shrimp fishing is deeply rooted in both the culture and economy of Louisiana. In the earliest days, shrimp was caught by hand-pulled seines and eaten mainly by Cajun settlers in a dried or salted form. But by the 1920s, refrigeration technology permitted trawl boats to travel farther distances for longer periods of time, which both increased landings and shifted production toward fresh and frozen shrimp that were much more appealing to U.S. consumers. By midcentury, consumer demand for shrimp far outstripped the seasonally limited supply, and shrimp came to be considered a luxury food with a high price tag.

Throughout the rest of the twentieth century, dockside prices for shrimp were fair and relatively stable. Shrimp fishing offered a secure living. Moreover, fishers’ identities are tightly bound up with the work they perform. Most commercial shrimp fishers are owner-operators of their vessels and value the independence that being their own boss provides. Shrimp fishing is also tightly linked to family structure. Most grew up on trawl boats and learned the trade from parents and grandparents. As such, many understand the pursuit as something they were born to do. As in other rural communities, their deep connection to the rich ecosystem of southern Louisiana has instilled a strong pride in their ability to “live off the land,” as they put it many times.

But around 2001, the industry—and this way of life—became imperiled. Dockside prices for shrimp tumbled precipitously and remained on a downward trajectory due to changes in the global economy for shrimp. Around this time, farm-raised imported shrimp flooded the U.S. market in unprecedented numbers. Since then, the increased volume of imported shrimp has decreased prices. This is good for shrimp-loving consumers, but it has been detrimental to those dependent on shrimp to earn a living.

Unlike many other rural workers who have faced industrial decline—farmers, miners, and loggers—shrimp fishers in Bayou Crevette have the unique option of securing well-paying jobs in the nearby oil industry. Many of these jobs require skills transferable from trawling (welding, engine repair, sea captaining, etc.). The lack of jobs has been shown by social scientists to be a catalyst for decline, but the case of Louisiana shrimp fishers permits an exploration of the noneconomic costs of occupational decline and job loss. After in-depth interviews with more than fifty individuals with ties to shrimp fishing, three primary patterns were observed in how folks responded.

First, some fishers, deemed “persisters,” acknowledged that they could earn a more secure living working in other jobs, but they chose to stay in the industry. They, therefore, have willingly opted to endure a host of financial and personal struggles to try to fulfill what they perceive as their cultural calling. The most common way shrimpers explained their reluctance to leave the industry is with the phrase “it’s in my blood.” With this simple expression, they demonstrated that trawling was not merely a job but represented a physical part of themselves and constituted the foundation of their family history and personal identity. Maintaining their identities as fishers was, for them, worth the very real economic struggles they endured. As a result of industrial decline, some fishers experienced struggles of poverty for the first time in their lives, particularly those who did not have working spouses.

Other fishers left the industry behind for better employment opportunities out of economic necessity. Many of these former shrimpers, the “exiters,” were better off financially, but many others experienced the exit as a personal tragedy. One ex-fisher carried a tattered photo of the boat that he sold in his wallet, which he pulled out when he said, “Losing my boat is like losing a baby. It hurts, you know? Like losing a baby.” Other fishers lamented having to sit behind a desk and take orders from higher-ups, a significant departure from life as a trawler and something they mourned. Most complained that their new work schedule prohibited them from spending the winter (the fishing off-season) hunting, an important part of rural culture. As one fisher put it, “We was born to hunt and trap in the winter and come back over here in the summer to shrimp.” In all, these narratives about the process and consequences of exiting show what workers lose when they leave behind a livelihood many considered to be their life’s calling.

Finally, a small but enterprising group of fishers, called “innovative adapters,” have changed their practices to adapt to the newly globalized market. In doing so, they remained viable producers while simultaneously preserving the meaningful occupational and cultural activities associated with their way of life. Adaptation requires two primary changes: (1) installing on-board freezers that enable fresh shrimp to be frozen the instant it is caught (increasing its quality and value), and (2) bypassing dockside processors to sell directly to consumers via farmers’ markets or through Internet businesses. Retrofitting boats to accommodate freezers is expensive, but as one fisher noted, “If we lose, we lose everything now, or we lose everything later. There’s no difference. We might as well try it. So we did, and so far we’ve been successful with it.” By using the Internet to find new and lucrative markets for their higher-quality catch, these local actors are not only fighting against global forces but are using globalization in a judolike fashion to advance their agenda.

From Louisiana shrimp fishers’ varied experiences with the globalization of their industry, we can gain a greater understanding of the importance of work in shaping our social and economic lives and our understanding of the world around us.

NOTES

1. An important factor underlying this pattern is the high rate of disability among prime age workers in the United States. In 2009, for example, the rate was 80 percent higher in rural (7.5 percent) than in urban areas (4.2 percent) (Bishop and Gallardo 2011).

2. Because the CPS uses a stratified cluster sampling design (i.e., it makes a special effort to incorporate groups that are harder to reach with surveys), it is necessary to use weights to produce reliable population estimates. In this analysis, the CPS person weights were divided by their means to yield weighted case sizes that are approximately equal to the sample size.

3. One state of underemployment—discouragement—described here is typically defined as “not in the labor force” because such workers are neither employed nor actively engaged in a job search. Underemployment brings these workers back into consideration.

Albrecht, Don E., and Stan L. Albrecht. 2000. “Poverty in Nonmetropolitan America: Impacts of Industrial, Employment, and Family Structure Variables.” Rural Sociology 65(1):87–103.

Barkley, David L., and Sylvain Hinschberger. 1992. “Industrial Restructuring: Implications for the Decentralization of Manufacturing to Nonmetropolitan Areas.” Economic Development Quarterly 6(1):64–79.

Bascom, Johnathan. 2000. “Revisiting the Rural Revolution in East Carolina.” Geographical Review 90(3):432–45.

Brady, David, Regina S. Baker, and Ryan Finnigan. 2013. “When Unionization Disappears: State-Level Unionization and Working Poverty in the United States.” American Sociological Review 78(5):872–96.

Broadway, Michael. 2007. “Meatpacking and the Transformation of Rural Communities: A Comparison of Brooks, Alberta and Garden City, Kansas.” Rural Sociology 72(4):560–82.

Brown, David L., and Nina Glasgow. 2008. Rural Retirement Migration. Dordrecht, Holland: Springer.

Burton, Linda M., Daniel T. Lichter, Regina S. Baker, and John M. Eason. 2013. “Inequality, Family Processes, and Health in the ‘New’ Rural America.” American Behavioral Scientist 57(8):1128–51.

Carr, Patrick J., and Maria J. Kefalas. 2009. Hollowing Out the Middle: The Rural Brain Drain and What It Means for America. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Citro, Constance F., and Robert T. Michael. 1995. Measuring Poverty: A New Approach. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Clogg, Clifford C. 1979. Measuring Underemployment: Demographic Indicators for the United States. New York: Academic Press.

Clogg, Clifford C., and Teresa A. Sullivan. 1983. “Demographic Composition of Underemployment Trends, 1969–1980.” Social Indicators Research 12:117–52.

Cotter, David A. 2002. “Poor People in Poor Places: Local Opportunity Structures and Household Poverty.” Rural Sociology 67(4):534–55.

Domina, Thurston. 2006. “What Clean Break? Education and Nonmetropolitan Migration Patterns, 1989–2004.” Rural Sociology 71:373–98.

Eckes, Alfred E. 2005. “The South and Economic Globalization: 1950 to the Future.” In Globalization and the American South, ed. James Charles Cobb and William Whitney Stueck, 36–65. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Falk, William W., and Thomas A. Lyson. 1988. High Tech, Low Tech, No Tech: Recent Industrial and Occupational Change in the South. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Falk, William W., Michael D. Schulman, and Ann R. Tickamyer. 2003. Communities of Work: Rural Restructuring in Local and Global Contexts. Athens: Ohio University Press.

Freudenburg, William R. 1992. “Addictive Economies: Extractive Industries and Vulnerable Localities in a Changing World Economy.” Rural Sociology 57(3):305–32.

Friedland, Roger, and A. F. Robinson. 1990. Beyond the Marketplace: Rethinking Economy and Society. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Fuguitt, Glenn V., David L. Brown, and Calvin L. Beale. 1989. Rural and Small Town America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Gibbs, Robert, Lorin Kusmin, and John Cromartie. 2005. “Low-Skill Employment and the Changing Economy of Rural America.” Economic Research Report No. 10. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Grusky, David B., Bruce Western, and Christopher Wimer. 2011. The Great Recession. New York: Russell Sage.

Hacker, Jacob S. 2008. The Great Risk Shift: The New Economic Insecurity and the Decline of the American Dream, rev. ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hamrick, Karen S. 2001. “Displaced Workers: Differences in Nonmetro and Metro Experiences in the Mid-1990s.” Rural Development Research Report No. 92. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Harrison, Bennett, and Barry Bluestone. 1988. The Great U-Turn: Corporate Restructuring and the Polarizing of America. New York: Basic.

Henderson, Jason. 2012. “Rebuilding Rural Manufacturing.” Main Street Economist 2:1–6. Kansas City, MO: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Holmes, Thomas J. 2013. “New Manufacturing Investment and Unions.” Economic Policy Paper 13–2. Minneapolis, MN: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Iceland, John. 2014. A Portrait of America: The Demographic Perspective. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Jensen, Leif, and Diane K. McLaughlin. 1995. “Human Capital and Nonmetropolitan Poverty.” In Investing in People: The Human Capital Needs of Rural America, ed. Lionel J. Beaulieu and David Mulkey, 111–38. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Jensen, Leif, and Tienda, Marta. 1989. “Nonmetropolitan Minority Families in the United States: Trends in Racial and Ethnic Economic Stratification, 1959–1986.” Rural Sociology 54(4):509–32.

Johnson, Kenneth M. 2011. “The Continuing Incidence of Natural Decrease in American Counties.” Rural Sociology 76(1):74–100.

Johnson, Kenneth M., and Daniel T. Lichter. 2008. “Natural Increase: A New Source of Population Growth in Emerging Hispanic Destinations in the United States.” Population and Development Review 34(2):327–46.

Joshi, Mahendra L., John C. Bliss, Conner Bailey, Lawrence J. Teeter, and Keith J. Ward. 2000. “Investing in Industry, Underinvesting in Human Capital: Forest-Based Rural Development in Alabama.” Society & Natural Resources 13(4):291–319.

Kandel, William, and Emilio A. Parrado. 2005. “Restructuring of the US Meat Processing Industry and New Hispanic Migrant Destinations.” Population and Development Review 31(2):447–71.

Kalleberg, Arne L., Barbara F. Reskin, and Ken Hudson. 2000. “Bad Jobs in America: Standard and Nonstandard Employment Relations and Job Quality in the United States.” American Sociological Review 65(2):256–78.

Kusmin, Lorin. 2014. “Rural America at a Glance, 2014 Edition.” Economic Brief No. EB-26. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture.

Lee, Marlene A., and Mark Mather. 2008. “US Labor Force Trends.” Population Reference Bureau Bulletin 63, No. 2.

Lichter, Daniel T. 2012. “Immigration and the New Racial Diversity in Rural America.” Rural Sociology 77(1):3–35.

Lichter, Daniel T., and David L. Brown. 2011. “Rural America in an Urban Society: Changing Spatial and Social Boundaries.” Annual Review of Sociology 37(1):565–92.

Lichter, Daniel T., and Kenneth M. Johnson. 2009. “Immigrant Gateways and Hispanic Migration to New Destinations.” International Migration Review 43(3):496–518.

Lobao, Linda, and Katherine Meyer. 2001. “The Great Agricultural Transition: Crisis, Change and Social Consequences of Twentieth Century US Farming.” The Annual Review of Sociology 27(1):103–24.

Lyson, Thomas A., and Charles M. Tolbert. 1996. “Small Manufacturing and Nonmetropolitan Socioeconomic Well-Being.” Environment and Planning A 28:1779–94.

Markhusen, Ann. 1980. “The Political Economy of Rural Development: The Case of Western US Boomtowns.” In The Rural Sociology of the Advanced Societies: Critical Perspectives, ed. Frederick H. Buttel and Howard Newby, 405–32. Montclair, NJ: Allenheld, Osmun.

McGranahan, David A. 2003. “How People Make a Living in Rural America.” In Challenges for Rural America in the Twenty-First Century, ed. David L. Brown and Louis E. Swanson, 135–51. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

McLaughlin, Diane K., and Alisha J. Coleman-Jensen. 2008. “Nonstandard Employment in the Nonmetropolitan United States.” Rural Sociology 73(4):631–59.

Morris, Martina, and Bruce Western. 1999. “Inequality in Earnings at the Close of the Twentieth Century.” Annual Review of Sociology 25(1):623–57.

Robinson, William I. 2001. “Social Theory and Globalization: The Rise of a Transnational State.” Theory and Society 30(2):157–200.

Slack, Tim. 2010. “Working Poverty Across the Metro–Nonmetro Divide: A Quarter Century in Perspective, 1979–2003.” Rural Sociology 75(3):363–87.

——. 2014. “Work in Rural America in the Era of Globalization.” In Rural America in a Globalizing World: Problems and Prospects for the 2010s, ed. Conner Bailey, Leif Jensen, and Elizabeth Ransom, 573–90. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

Slack, Tim, and Leif Jensen. 2002. “Race, Ethnicity, and Underemployment in Nonmetropolitan America: A 30-Year Profile.” Rural Sociology 67:208–33.

——. 2004. “Employment Adequacy in Extractive Industries: An Analysis of Underemployment, 1974–1998.” Society and Natural Resources 17:129–46.

——. 2010. “Informal Work in Rural America: Theory and Evidence.” In Informal Work in Developed Nations, ed. Enrico A. Marcelli, Colin C. Williams, and Pascale Joassart, 175–91. New York, NY: Routledge.

Slack, Tim, and Tracey E. Rizzuto. 2013. “Aging and Economic Well-Being in Rural America: Exploring Income and Employment Challenges.” In Rural Aging in 21st Century America, ed. Nina Glasgow and E. Helen Berry, 57–75. New York: Springer.

Smeeding, Tim. 2006. “Poor People in Rich Nations: The United States in Comparative Perspective.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20:69–90.

Snipp, C. Mathew. 1996. “Understanding Race and Ethnicity in Rural America.” Rural Sociology 61:125–42.

Sommer, Judith E., et al. 1998. “Structural and Financial Characteristics of US Farms, 1995.” Twentieth Annual Family Farm Report to Congress, No. 33620. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture.

Stamps, Katherine, and Stephanie A. Bohon. 2006. “Educational Attainment in New and Established Latino Metropolitan Destinations.” Social Science Quarterly 87(5):1225–40.

Sullivan, Teresa A. 1978. Marginal Workers, Marginal Jobs: Underutilization of the US Work Force. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Tonelson, Alan. 2002. The Race to the Bottom: Why a Worldwide Worker Surplus and Uncontrolled Free Trade Are Sinking American Living Standards. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Vias, Alexander C. 2012. “Perspectives on US Rural Labor Markets in the First Decade of the Twenty-First Century.” In International Handbook of Rural Demography, ed. Laszlo J. Kulcsar and Katherine J. Curtis, 273–91. Dordrecht, Holland: Springer.

Weber, Bruce, Leif Jensen, Kathleen Miller, Jane Mosley, and Monica Fisher. 2005. “A Critical Review of Rural Poverty Literature: Is There Truly a Rural Effect?” International Regional Science Review 28(4):381–414.

Weil, David. 2014. The Fissured Workplace. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Western, Bruce, and Jake Rosenfeld. 2011. “Unions, Norms, and the Rise in US Wage Inequality.” American Sociological Review 76(4):513–37.