Catharine Biddle and Ian Mette

Child poverty remains one of the greatest obstacles to educating youth today, with the largest proportion of American children living in poverty located in rural areas (Brown and Schafft 2011; Iceland 2006). Schools, as the chief publically funded social institution responsible for children’s development, are often championed by the media and policy makers alike as being the primary engine of future social equality (Gerstl-Pepin 2006). What remains unacknowledged in this paradigm, however, is that schools across the United States are often unintended contributors to perpetuating inequality through practices that disproportionately target marginalized and impoverished youth (Noguera 2003). This marginalization begins with the assumption by schools and policy makers that poverty is a universal phenomenon that is both constant (one either is poor or is not) and aspatial (there is no difference in the experience of childhood poverty across urban and rural contexts). In reality, research on poverty throughout the United States suggests that as many as 65 percent of Americans take advantage of welfare benefits by the time they are 65 (Ludwig and Mayer 2006; Rank and Hirschl 2002) and that poverty as a lived experience is a diverse and highly contextualized phenomenon (Blank 2005; Sherman 2014). Factors such as the size of one’s community, whether one attends a rural or urban school, the network of social services, and the willingness of people to use them dictate much about the experience of childhood poverty across contexts (Blank 2005; Sherman 2009, 2013, 2014).

Contextual differences also play a role in local perceptions of the promise of education to create social equality in a community. Depending on the geographic, social, and economic needs of a community, the meaning ascribed to the skills, knowledge, and aspirations cultivated by schools may develop differently (Budge 2006, 2010). The meaning and implications of a “college and career ready” federal agenda for education, for example, might be read in divergent ways by urban areas where postsecondary training and colleges are located in the community itself versus rural areas where few such opportunities are available locally (Corbett 2007; Wright 2012). The implications of such an agenda for each community, therefore, differ: urban and suburban youth may enjoy the benefits of postsecondary training while staying firmly connected or even continuing to live within their communities, whereas rural youth often must leave their communities and local support systems to pursue such opportunities (McDonough, Gildersleeve, and Jarskey 2010). With such an example, it is possible to see how the notion that “all of America’s youth must go to college” might evoke differing responses from people in different places.

The implications of such contextual differences for rural schools in understanding and meeting the needs of students and their families experiencing poverty are explored in this chapter. Rural schools are often closely linked to the communities they serve, both as one of the few local social institutions and as a site of intergenerational connection and community pride (Lyson 2002). However, as part of a national system of public education, rural schools find themselves subject to extralocal educational priorities and mandates that impede their ability to serve their communities well (Biddle and Schafft 2016; Sipple and Killeen 2004). These competing priorities can lead rural communities to ask difficult questions of their schools, such as how education will fulfill its promise locally and, perhaps more important, whose purposes education really serves (Schafft 2010). Rural schools’ responses to these questions, as well as their ability to adequately serve the needs of their poorest students, are bound up in a complex web that includes the legacy of American antipoverty policies of the twentieth century, governmental responses to the current economic and financial ethos and system, and schools’ obligation to shoulder the burden of performance-based accountability reporting mandated by twenty-first-century educational reforms.

To understand these complexities, the relationship between childhood poverty, education, and youth development is described across contexts, and the formal mechanisms that schools have inherited for addressing and responding to poverty are explained. School funding mechanisms may disadvantage rural schools, and the bias against rural environments in the design of federal and state education policy is described. The cumulative effect of these issues on the resulting organizational capacity of rural schools to effectively meet the unique needs of their communities and, in particular, the needs of students and families experiencing poverty is explored. The chapter concludes with a discussion of counternarratives and the possibility that rural school innovations can address childhood poverty and community economic development. Contemporary policy developments that may enhance or constrain this responsiveness are also addressed.

AN OVERVIEW OF CHILD POVERTY AND SCHOOL SERVICES

The effects of childhood poverty on social, emotional, physical, and health development are profound and affect the development of individuals living in poverty throughout their life span (Jones and Sumner 2011). Children who experience ongoing and persistent poverty are more likely to have negative health effects due to a lack of adequate nutrition (Korenman and Miller 1997), and they may experience a lack of access to adequate health and social services (Hanson, McLanahan, and Thomson 1997). Moreover, the ability for parents to invest in the development of their child, including but not limited to instilling the value of education, making informed health decisions, and passing along knowledge about making wise financial decisions, is also affected by poverty (Duncan and Brooks-Gunn 2013). What results is a cycle of reinforcement that can lead to intergenerational poverty, reinforcing a common misconception among Americans that poverty is due to a lack of work ethic or moral values rather than being a cycle reinforced by social and economic conditions (Sullivan 2011; Swanson 2001). Poor children are three times more likely not to complete high school, are twice as likely to have a teen pregnancy, and will earn upward of 40 percent less in mean family income (Corcoran 2009).

Childhood poverty also has a significant impact on brain development. Although there is no discrepancy in cognitive ability among socioeconomic and racial groups of American infants (Ferguson 2007), children who experience persistent poverty are negatively affected in their IQ as well as verbal communication, and they score lower on achievement tests (Smith, Brooks-Gunn, and Klebanov 1997). However, environment greatly influences the ability of children experiencing poverty to fully maximize their genetic intellectual ability (Berliner 2006). In addition, childhood poverty, specifically the lack of exposure to early childhood education and the inability for parents to provide adequate health and social services early in life, negatively affects classroom behavior and increases the likelihood of behavioral maladjustment (Lipina and Colombo 2007). What results is a negative impact on the well-being of children living in poverty, which creates a domino effect on learning and creates education gaps.

FEDERAL MEASURES TO ADDRESS ISSUES ASSOCIATED WITH CHILDHOOD POVERTY

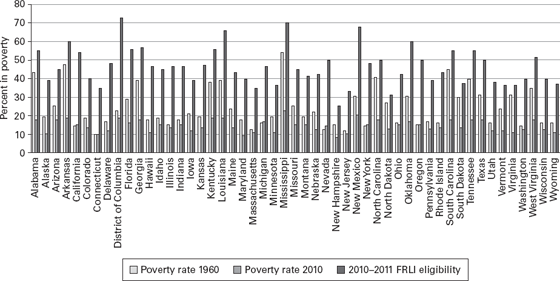

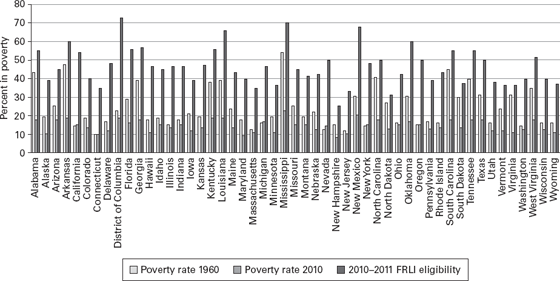

The evolution of both educational policy and formal school services to address childhood poverty has been intimately tied to federal social policy. Over the past fifty years, the United States has attempted to broadly address socioeconomic inequities through a variety of policy measures. Starting with President Lyndon Johnson and the War on Poverty in 1964, an assortment of antipoverty policies were proposed to address changing global economies, labor markets, and education and health care systems (Cancian and Danzinger 2009). These policies included creation of programs such as Medicaid, Medicare, and Head Start, as well as the expansion of benefits provided through Social Security (Danziger and Haveman 2001), all of which were aimed at reducing childhood poverty. As a result, from the 1960s through 2010, states throughout the rural South, once considered the most impoverished region of the United States, reduced poverty rates by more than half (see figure 12.1). Only a few states, including California, Michigan, Nevada, New York, and Oregon, saw poverty levels increase during this time span.

Figure 12.1 Change in poverty rates in the United States from 1960 to 2010.

Source: Adapted from Poverty Rates by County, 1960–2010, U.S. Census Bureau (2010a) and NCES free and reduced lunch rate eligibility (2012).

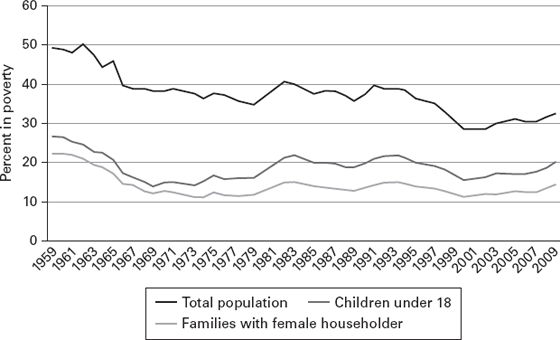

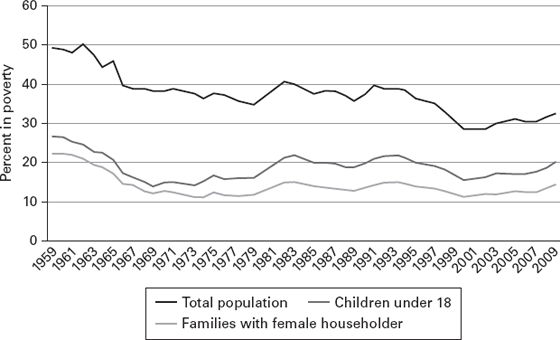

Although impressive and important, antipoverty policies and their influence on reducing childhood poverty had their greatest impact prior to 1970, after which their effect began to diminish. From 1960 to 1969, poverty rates for children under eighteen dropped from 26.5 percent to an all-time recorded low of 13.8 percent (U.S. Census Bureau 2010); from 1970 onward, a widening gap began to emerge between the percentage of Americans living in poverty and the percentage of American children under eighteen living in poverty (see figure 12.2). Moreover, as a result of gender wage inequity, 44 percent of children living in female headed households are now living in poverty as opposed to 11 percent in married couple households (Cancian and Reed 2009; Haskins 2012). The reality is that in the United States today, almost one-third of children will experience poverty at some point in their life, with 29 percent of those living in rural places compared to 21 percent in urban areas (O’Hare 2009). As a result, there has been increasing pressure on schools, particularly in rural places, to address the host of developmental and social issues associated with increased numbers of children experiencing poverty (Berliner 2006).

Figure 12.2 Segments of American population living in poverty.

Source: Adapted from Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2009, U.S. Census Bureau (2010b).

Since the 1960s, an evolving patchwork of federal and state policies has been crafted to leverage the daily contact schools have with poor children to mitigate or ameliorate the developmental and cognitive effects of living in poverty. Perhaps none has been more profound than Title I, part of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965. Born from the same political efforts of the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty, the purpose of Title I was a “national commitment to help educate economically and educationally disadvantaged children” (Jennings 2001, 1). The federal government disburses funds to state agencies of education, which in turn distribute these funds to schools serving economically disadvantaged populations of children. The introduction of Title I funds as a financial support for schools in the 1960s was the first time the federal government systematically provided funding for education in the United States, and over the past few decades this has led to increasing federal involvement and oversight in education (Kaestle and Smith 1982). The most recent and perhaps farthest reaching examples of this oversight are the accountability measures for schools that were introduced as part of the reauthorization of ESEA, also known as No Child Left Behind.

Another important federal intervention effort to help reduce the impacts of childhood poverty, specifically the impact on homeless youth, is the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. First authorized in 1987, the McKinney-Vento program ensures that homeless children remain enrolled in their school despite changes to their residential status, and it requires the school to provide transportation to school from wherever the children are living (U.S. Department of Education 2004). In 2000, over 580,000 American children grades K–12 were served by the McKinney-Vento program, and more than 19,000 preschool students were served as well (U.S. Department of Education 2006). These services attempt to minimize the impact of housing insecurity on children’s education by eliminating the disruption of services and learning loss that accompanies transitions between different schools. It is difficult to measure the number of homeless in rural places, in part because rural homelessness often takes the form of doubling-up with family or friends or staying in substandard housing, but available studies indicate that the rural homeless are more likely to be families with children than the homeless in urban or suburban areas, reinforcing the importance of this program for remote and rural districts (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2013).

One of the most recognizable federal programs that helps address poverty in schools is the National School Lunch Program, which provides free meals to students with a family income at or below 130 percent of the poverty level and reduced price meals to students with a family income between 130 and 180 percent of the poverty level (National Center on Education Statistics 2015). The belief undergirding this intervention is that when children come to school hungry they are unable to learn. The National Center for Education Statistics (2015) reports varying levels of free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL) usage by state and locale.

Although all of these federally funded services are designed to take advantage of the daily contact between children experiencing poverty and schools, it can be challenging for rural schools in particular to fulfill the intention of these policies in practice. For example, 70 percent of qualifying families in urban areas enroll their children for free and reduced price lunches, but only 63 percent of qualifying rural families enroll their children in this program (Carson 2015). Stigma around social assistance in small communities may play a role in depressing the use of these programs for eligible families in a way that is different from larger, urban settings (Sherman 2009). It is imperative for schools to reach out to families to identify their eligibility and ensure services for their students, but rural schools face additional challenges because of their constrained organizational capacity in the face of diminishing school funding and school policy mandates. In the following sections, the pressure that inequitable school funding and the invisibility of rural school’s unique needs in state and federal policy making is discussed.

THE EFFECTS OF SCHOOL FUNDING ON RURAL SCHOOLS AND POOR FAMILIES

Schooling in the United States, unlike many other countries, historically has been a highly decentralized system that relies on state monies and local financial support, often in the form of property taxes, to fund local public schools (Baker, Sciarra, and Farrie 2014). As a result, the local economy has a profound effect on the funding a school receives and, in turn, the capacity of that school to provide educational amenities and services to its students (Tyack 1972). Pockets of concentrated poverty within the United States, such as communities where poverty exceeds 20 percent or even 30 percent of the population, can translate into both a reduced ability for local municipalities to fund their schools and an increased need for higher-cost school services (Dayton 1998; Massey 1996). These services include special education, English language learning support, supplemental services (such as after-school tutoring), and coordination of services for transient students (Baker et al. 2014).

Such concentrated disadvantage has been exacerbated for many rural places in the last fifty years as their local economies have increasingly become tied to the global economy. This has resulted in the outsourcing of jobs to other countries, the introduction of megastores that outcompete locally owned businesses through competitive global supply chains, and the restructuring of companies to be less bound to a particular location so that they can shift geographically and be more responsive to changes in global markets (Goetz and Swaminathan 2006; Urry 2005). Some rural communities have found viable alternative means of sustaining the local economy, but for others these changes have meant increasingly constricted local opportunities for work, the introduction of economic uncertainty, and, in some cases, complete economic collapse (Sherman 2009, 2014). Since the 2008 recession, employment has continued to rebound more slowly in rural areas than in urban areas (U.S. Department of Agriculture 2015). These realities, in turn, affect local migration patterns of both adults and young people in search of work and devalue local property as the community becomes less attractive to potential newcomers (Lyson 2002). Together, these factors contribute to chronic declining enrollments of students in schools across rural America (Schwartzbeck 2003; Jimerson 2007).

STATE-LEVEL FUNDING INEQUITY

These changes have more recently become compounded by pressure on some state education agencies to be increasingly fiscally conservative when it comes to funding public amenities and services. In 2015, thirty-one states provided less school funding per student than prerecession levels. For fifteen of these states, the difference exceeded 15 percent of the pre-2008 funding levels (Leachman, Albares, Masterson, and Wallace 2016). As state agencies tighten their belts in response to fiscal political pressure, greater pressure is placed on local communities to make up the gap in funding state and federally mandated school services and in meeting the basic educational needs of students in their schools. However, the economic capacity of many of these communities often has been eroded by the realities of the global economic system far beyond the control of local residents. As a result, some rural communities have to consider closing their schools due to an inability to fund them, which has devastating effects on community vitality and can reinforce patterns of economic decline and marginalization (Lyson 2002).

Even prior to these more recent budget cuts, the existing mechanisms for state provision of funds to local schools had been accused of having an unfair bias against small and rural schools. To understand these claims, it is important first to understand how state agencies of education provide funding to schools. Equity in school funding can be understood as existing along two equally important dimensions: the overall level of funding allocated to public schooling for the whole state and the distribution of that funding (Baker et al. 2014). To determine distribution of funds, states create a funding “formula,” typically based on the number of students served by a school (Imazeki 2007). Structured differently in each state, these formulas may provide similar per pupil funding to all districts with varying needs (referred to as “flat” funding), greater funding to districts with higher concentrations of students in poverty, or less funding to districts with higher concentrations of poor students (Baker et al. 2014). Although regressive funding systems that provide less money to districts with greater need might appear counterintuitive, these funding systems often occur when overall state funding to districts is low and no cap is placed on local spending. This allows rich districts with high property values and affluent citizens to outspend poorer districts that are without these economic advantages.

School districts with high concentrations of poverty often suffer in this system. Nationally, thirty-four states employ funding formulas that provide either flat funding to districts or provide less state and local funding to districts with higher concentrations of poverty (Baker et al. 2014). However, rural districts with high concentrations of poverty are often doubly disadvantaged by state funding formulas, which rely on enrollment numbers for total allocation. As enrollments decline and they receive fewer funds, rural schools are still responsible for the many mandated costs associated with maintaining a public school and associated student services, in addition to costs unique to these schools, such as higher transportation costs (Jimerson 2007). The result is often budget cuts to teaching positions in subject areas such as art, physical education, or music, which are not subject to state standardized tests. Conversely, budget reductions may occur through the defunding of amenities such as libraries, sports teams, or support services. These differences have not gone unchallenged by rural districts, however. In 2011, rural plaintiffs brought eight active cases with constitutional challenges to state school funding inequity across the United States, and twenty-seven out of thirty-two such cases in previous years were brought by rural plaintiffs as well (Dayton 1998; Strange 2011).

FEDERAL FUNDING INEQUITY

A small portion of the funding schools receive consists of federal financial support in the form of Title I funds, which schools are entitled to if they serve qualifying populations of students. Other federal funds are disbursed through competitive grants directly to districts or to state education agencies (Rural School and Community Trust 2011). Rural schools face several unique challenges in competing for federal grant monies. First, many rural school districts maintain a relatively small number of district-level staff, so their capacity to identify and write proposals for such grant money is more limited than that of larger districts in suburban and urban areas that typically employ more educators (Johnson, Mitchell, and Rotherham 2014). Second, grant programs, like school funding formulas, often disburse funds based on the number of students in a district rather than on the stated need, so rural districts may end up with grants that are too small to cover their intended purpose (National Education Association 2015).

The compounded effect of local economic conditions and both state and federal funding inequities affects the organizational capacity of rural schools to effectively address issues associated with childhood poverty in rural communities. As a result, rural schools may find that strategies that work for suburban or urban schools to better combine and leverage financial resources remain unrealistic in their communities (Dayton 1998). The pressure to employ such strategies has increased in recent years, however, because federal and state oversight has increased.

URBAN-CENTERED EDUCATIONAL POLICY AS FEDERAL PRACTICE IN EDUCATION

Since the 1960s, the federal role in America’s traditionally decentralized education system has increased. The introduction of ESEA in 1964 and Title I funds for schools serving low-income populations brought about this increase in federal power (Welner and Chi 2008). Liberal policies of the 1960s aimed to increase social equity among Americans, but release of the commissioned report A Nation at Risk in 1983 spurred a shift in federal priorities. American educational performance was framed as being key to overall global U.S. economic competitiveness (Schafft 2010). Policy makers began increasingly to focus their interventions in education on maintaining and expanding global U.S. economic power (Au 2010). This interest coincided with a shift in economic policy toward a neoliberal schema that placed increasing value on the strength of the free market and individual consumer choice, rather than state regulation, to drive economic prosperity and growth (Harvey 2005).

Over the past thirty years, these neoliberal economic policies have influenced education policy by increasingly positioning education as an individual good rather than a collective one meant to develop human capital that could respond to the liquidity and rapid mobility of an increasingly global economy (Bauman 2001). As a result, educational reforms have focused on promoting market-based competition between schools and school choice, increasing standardization of curriculum, and big data (Ball 2004; Au 2010; Schafft 2010). Recent policies, such as No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top, have ostensibly been designed to promote equity and quality education for low-income youth, but they were conceptually designed based on urban and suburban settings. The complex relationship of rural places and neoliberal economic agendas has meant that these programs have struggled to fulfill their promise in rural schools (Jimerson 2007; Schafft 2010).

THE IMPLICATIONS OF NO CHILD LEFT BEHIND AND RACE TO THE TOP FOR THE RURAL POOR

With the introduction of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) in 2001, the federal government mandated that states implement accountability measures that influenced the assessment of students, qualifications for teachers, and funding and restructuring for low-performing schools (Irons and Harris 2007). The premise was that a more centralized accountability structure would force states to give greater attention to equity between populations that were ignored or marginalized in the past, particularly low-income students and students with special needs (Welner and Chi 2008). To support these efforts, NCLB placed new reporting and data management responsibilities on districts, provided requirements for whom districts could hire, and graded district performance in large part on annual state tests measuring student performance in math and reading (Linn, Baker, and Betebenner 2002).

These requirements placed additional burdens on all school districts and were particularly challenging for many rural districts (Jimerson 2005a, 2005b; Hodge and Krumm 2009). The highly qualified teacher provision of NCLB, which requires teachers to have a bachelor’s degree, a teaching license, and demonstrable knowledge of each subject area taught, disrupted shared staffing arrangements in already hard to staff schools and reduced definitions of “teacher quality” to degree requirements rather than skill or expertise in working with the unique needs of students in rural contexts (Brownell, Bishop, and Sindelar 2005; Eppley 2009; Hodge and Krumm 2009). If schools failed to make adequate yearly progress (AYP) and meet the benchmarks for proficiency in reading and math set out by the law in 2002, they were labeled as failing schools and were subject to additional requirements. Some of these requirements, such as the provision of supplemental educational services for low-income students, were well meaning but difficult for rural schools to implement without the rich network of private providers available in urban areas (Barley and Wegner 2010; Jimerson 2005b); others, such as the opportunity for school choice for students in failing schools, were almost impossible for districts to shoulder in the face of shrinking budgets and remote locations (Jimerson 2005b).

Recognizing the difficulties for districts associated with these accountability measures, the Obama administration used the opportunity presented by the large allocation to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in 2009 to create the Race to the Top competition and School Improvement Grants programs (U.S. Department of Education 2015). These incentive-based programs opened competitive grants up to both states and school districts. To be competitive for these funds, however, states had to agree to a series of policy conditions, including teacher evaluation systems tied in part to student test scores, the founding and expansion of charter schools in their states, and specific reconstitution or reform practices in the lowest performing 5 percent of schools in the state (McGuinn 2011).

These programs, too, were difficult for rural states and school districts to use to their advantage. Many rural states have been hesitant to introduce legislation allowing charter schools in the face of already declining student enrollments due to the hollowing out effect this might have on districts’ ability to continue to serve a diversity of students in small communities (Clancy 2015). Value-added models of teacher evaluation that rely on evaluating teacher performance through measuring increases in student test scores may be unfair to rural teachers or teachers with a high number of mobile or transient students whose small class sizes mean that the student performance from year to year might vary widely (Corcoran 2010; Goetz 2005). In addition, the models required by Race to the Top and School Improvement Grants for reform among the bottom 5 percent of schools were premised on dense populations supporting flat or increasing student enrollment and robust labor markets for educators—qualities that most rural districts simply do not have (Mette 2013). It is no wonder, then, that out of the states that received the initial and second round Race to the Top funds, only three out of twelve states were predominantly rural and none had high concentrations of rural poverty (Rural School and Community Trust 2010).

These federal policies are two examples of the ways in which current trends in reform often favor urban and suburban school districts that support larger student bodies and thus have a larger budget to respond to reform initiatives (Baker et al. 2014). Marginalized populations in rural places under such a system may be doubly disadvantaged because they are repositioned as a liability in a system of resource scarcity and ill-fitting policy (Schafft, Killeen, and Morrissey 2010). Rural places, with less population, also often have little political economy to advocate for change. As a result, the organizational capacity of rural schools to address the needs of their most vulnerable populations are often constrained.

EFFECT OF URBAN-CENTERED SCHOOL FUNDING AND POLICY REGIMES ON RURAL SCHOOLS

Funding and political biases have played an important role in shaping the organizational capacity of rural schools to meet the economic and educational needs of rural communities and, in particular, the unique needs of poor children and families in those communities (Corbett 2007; Schafft 2010). Low funding levels overall and a funding distribution system based on population density create a context of scarcity in which individual funding priorities have a greater impact than in contexts of plenty, and neoliberal educational policies affect what schools are forced to designate as priorities in the first place. The combined effects of scarcity and an increased federal role in determining local education agency priorities translates into a constrained ability of rural school systems to make choices that are responsive to the unique needs of their communities and their schools’ families. In particular, rural schools may find it more difficult to recruit and retain educators who understand their community needs, to provide special services that meet the needs of their learners, and to give nuanced messages to young people about their future prospects both within and outside their rural community.

TEACHER LABOR MARKETS AND SCHOOL SERVICE PROVISION

Historically, recruiting trained teachers to rural areas always has been difficult. With the professionalization of teaching, the necessity of teaching credentials, and the centralized location of many teacher training institutes (formerly called normal schools) within cities, rural school reformers in the early twentieth century often lamented the difficulties of convincing newly trained educators to move to rural places without the attractions of urban life (Biddle and Azano 2016). The necessity of offering lower salaries than those in urban or suburban districts combined with the remote or distant locations of many rural schools make rural teaching posts less attractive to new teachers today (Schwartzbeck 2003).

Retention of rural educators can be difficult as well because rural teaching posts often entail a greater diversity of responsibility while at the same time being more isolated than teachers in other contexts. Rural teachers are more likely to be teaching multiple subjects or teaching outside of their content area (Eppley 2009), yet rural teachers often have fewer opportunities to attend professional development courses that would enable them to supplement and enhance their existing skills (Howley and Howley 2005). Generally, frequent contact with other educators through professional development or strong district-level networks provides teachers with opportunities to discuss, compare, and improve their teaching practice based on the insights of others (Snow-Gerono 2005). Without these opportunities, rural educators may feel they have to reinvent the wheel to solve every problem of practice they face (Howley and Howley 2005). This professional isolation can lead to poor morale or to a sense of helplessness in the face of organizational and community challenges, particularly in areas of concentrated economic disadvantage (Schlichte, Yssel, and Merbler 2005). As a result, teachers may be attracted to geographic areas with higher salaries and fewer challenges. These staffing and infrastructural issues, as well as budgetary concerns and the impact of policy on school priorities, result in fewer course offerings, particularly in advanced-level courses, as well as a stricter emphasis on testable skills such as reading, math, science, and writing (Bouck 2004; Khattri, Riley, and Kane 1997).

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SCHOOLING, YOUTH ASPIRATIONS, AND OUT-MIGRATION IN RURAL PLACES

One of the most complex aspects of the relationship between rural schools and rural communities is the role of the school in encouraging youth out-migration from rural places (Gibbs and Cromartie 1994; McLaughlin, Shoff, and Demi 2014). Public schools are tasked with the responsibility of developing youths’ skills, or human capital, to serve the needs of both local and national economic and civic growth (Corbett 2015). However, the evolving nature of the U.S. economy, with its decreased emphasis on manufacturing and other forms of labor and increased focus on service and technological innovation, means that secure future employment now requires higher levels of education than were needed in the past (Petrin, Schafft, and Meece 2014). As a result, the necessity of higher education and postsecondary training has never been more important than it is today. However, the dearth of opportunities to receive this training within or near rural communities means rural youth often must leave their communities to continue their education (Wright 2012). Although it is hoped that youth who leave their communities to complete their education will return, limited job opportunities in their hometowns are available for students with such training or higher education to use the skills they have gained (Petrin et al. 2014).

This reality creates an ambivalence among many educators as to how to approach their engagement with the aspirations of rural youth. For many, the economic decline and low-wage opportunities available in rural communities mean that encouraging any aspiration other than college-going does not seem to be in any individual student’s economic best interest (Budge 2010). However, in other places, this ambivalence is born from the sometimes rapidly changing economic contexts that characterize some rural places today (Corbett 2007). The dynamism of many industries and their globalized approach to managing their industrial portfolios mean that rapid cycles of boom and bust may create unrealistic hope for youth that lucrative, long-term labor opportunities that appear overnight in their communities are a sustainable path for a future in their hometowns (Schafft and Biddle 2014, 2015). Although educators acknowledge that these industries might allow young people the opportunity to gain experience and earn large amounts of money, many wonder whether these short-lived windfalls will lead to sustainable future employment or saving for other opportunities in the future (Schafft et al. 2014).

In either case, rural schools are in the difficult position of playing a role in who stays and who leaves their communities. Carr and Kefalas (2009) suggested that schools intentionally encourage high-achieving students to leave the community by investing energy and resources in their success while ignoring the development of the lower-achieving students who ultimately end up staying and becoming the remaining population of the area. However, Petrin and colleagues (2014) suggest that, in fact, student perceptions of local economic conditions play a far greater role in determining whether high achievers ultimately return to their communities.

The institutional capacity of rural schools to address the needs of vulnerable and economically disadvantaged children and families in their communities is severely constrained by a political system that ignores the unique needs of rural places, an economic system that positions youth as mobile human capital disembedded from the places where they grew up, and a school funding system that distributes funds on the basis of numbers and not need. This combination of factors can give rise to an ethos among educators that poverty is a problem beyond their reach (Dutro 2010). Many express powerlessness in the face of an eroded organizational capacity, already overburdened trying to meet the demanding needs of federal and state accountability measures (Schafft, Killeen, and Morrissey 2010).

In December 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) was passed, which reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. ESSA attempts to eliminate some of the more punitive measures for failing schools introduced in both No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top (U.S. Department of Education 2015). It is unclear, however, what, if any, changes this will mean for rural schools around their capacity to more effectively address the unique needs of children experiencing poverty. The law does financially support the expansion of the Promise Neighborhoods program, an approach to school–community partnerships and wraparound services that aims to ensure that all children “have access to great schools and family and community support that will prepare them to attain an excellent education and successfully transition to college and a career” (U.S. Department of Education 2015). However, even in the rhetoric surrounding these promising practices, it is clear that the philosophical positioning of youth as labor for a global economy has not changed, and schools will still be held accountable to that vision of educational purpose with, in the words of U.S. Secretary of Education, “new and smarter tests” (Duncan 2015). Fundamentally, the pressure to teach to standardized tests and encourage students to pursue careers and further education outside their communities will likely still limit the ability of rural schools to be responsive to their unique community needs.

There is hope, however, because some rural districts across the country are engaging in innovative school–community partnerships designed to address the unique needs of vulnerable rural families and children. Examples in all areas of community life are evident. In Pennsylvania, a district superintendent worked with a local broadband company to ensure that high-speed Internet access is available at an affordable price not only for the school but for local families in their homes (Schafft, Alter, and Bridger 2006). In Wyoming, taxes on profits from mineral and petroleum extraction fund public education across the state at a rate of per pupil funding second only to Massachusetts (Bake et al. 2014). In the borderlands of rural Texas, the Llano Grande Center was founded by Mexican American youth and public school teachers to give youth an opportunity to conduct action research within their communities and school to find new ways of doing school reform at a local level (Guajardo et al. 2006). In rural Vermont, Unleashing the Power of Partnership for Learning tackles similar community and school reform issues in New England schools by building the capacity of youth and teachers to do action research together (Biddle 2015). In Cody-Kilgore, Nebraska, a youth business class built and now runs a community grocery school for local families—the only such amenity within forty miles of the town (Rural Schools Collaborative 2015).

What remains to be seen, however, is the extent to which these individual grassroots partnerships are capable of inspiring and maintaining a focus on meeting the needs of economically vulnerable families in rural places as they enhance opportunities for learning through youth leadership experience and project-based learning that inform the future citizens of these rural locations. Within the current political and financial context, it is too easy for schools to overlook or ignore the needs of these students, or worse, to see them as a liability in the face of mandates and fiscal constraint. However, it is imperative for schools, districts, and state education agencies to maintain their focus on meeting the needs of economically vulnerable families in rural places for the long-term health of these communities.

Kai A. Schafft

The Marcellus Shale play is a natural gas–bearing geologic formation a mile below the earth’s surface. Underlying about two-thirds of mostly rural Pennsylvania, and extending into parts of West Virginia, New York, Ohio, and Maryland, geologists have long recognized that the Marcellus formation contained significant amounts of natural gas. However, it wasn’t until technological developments in the 2000s created conditions for the economically feasible large-scale commercial extraction of shale gas that the Marcellus Shale and other similar “unconventional” natural gas reservoirs1 began to be actively developed. By 2007, unconventional natural gas extraction in Pennsylvania had begun in earnest, and by the end of 2016, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protect well count “spud” data showed there were more than 10,000 unconventional gas wells across the shale gas regions of the state.

Much of this so-called boomtown development has taken place in mostly rural areas that have experienced years of economic contraction with few anticipated prospects for economic development. For example, by the middle of 2010, when the shale gas boom was near its peak, just one of the fifty wealthiest school districts in Pennsylvania had experienced any unconventional gas drilling, with only a single well. By contrast, of the fifty poorest school districts, eighteen had shale gas development with a total of 364 wells (Kelsey et al. 2012). New workers and industrial activity raised expectations of economic benefits for local people and communities, hopes reinforced by gas industry advocates and enthusiastic pronouncements from the Pennsylvania governor’s office (Schafft and Biddle 2015).

Schools experienced these local changes in a number of different ways. The expectation among many administrators was that enrollments would rise, which was a development to be welcomed by many given historical trends of enrollment decline in much of the Marcellus region. This did not happen, however, because the majority of out-of-state workers did not necessarily intend to relocate to Pennsylvania permanently, and those with families, for the most part, tended to leave their families behind. What teachers and administrators did notice, however, was an uptick in homeless students, even in school districts in which homelessness had not occurred in recent memory.

A superintendent from a heavily drilled county on the New York border explained:

At my school I’ve seen the impact, I think, mostly in housing. I find that the people who are coming from mostly Texas and Oklahoma and the adults are just working on sites. They might be here a couple of months and then they are gone…. Rentals of apartments and housing have skyrocketed so our own native people who tend to be fairly transient, moving from one place to another, can’t find anywhere to live. This is the first year, I’ve been in education for thirty-five years, this is the first year I’ve ever known of some of my students being homeless. In fact, I have a family that has been evicted and they have to be out today and they don’t have anywhere to go. Also a lot of these gas people bring fifth wheels or, uh, campers, and families are living in campers so we have a family with two or three kids and they’re living in the camper, which I can’t even imagine.

Homelessness represents an indicator of extreme social need. For educators, student homelessness is additionally a concern because of the disruption it poses to the social and academic lives of students. This disruption often results in academic underachievement and increased risk of dropping out. For schools and administrators, homelessness and student mobility also can result in significant administrative, education, and record-keeping challenges (Killeen and Schafft 2015).

Many educators noted the new incidence of homeless students whose families had been priced out of rental housing, and superintendents began to talk about a second group of technically homeless students sometimes referred to as the “Hummer homeless,” students of gas worker families temporarily residing in the district in recreational vehicles and driven to school in their parents’ Humvee. Although living in households with an income far above the poverty line, nonetheless these students were classified as homeless according to federal guidelines because of their residence in a temporary or nonstandard dwelling. Although an apocryphal story, it neatly encapsulates the frustration and contradictions felt by many administrators, especially as other longer-term residents found themselves priced out of local rental housing, unable to secure housing assistance, and making do by couch surfing and temporarily doubling-up with friends and other family members.

In public discourse, natural resource development is often equated with local economic development, despite a growing body of “resource curse” scholarship suggesting the underwhelming or even negative long-term local economic outcomes of such development (e.g., James and Aadland 2011; Matz and Renfrew 2015). What is less well recognized, however, are the uneven social and economic outcomes of boomtown development that occur not only in the midst of rapid development but often precisely because of that development. Rural poverty often is described according to its “invisibility,” even though poverty in the United States has historically been concentrated in nonmetropolitan areas (Brown and Schafft 2011; Tickamyer 2006). The economic insecurities accompanying rural boomtown development are all the more invisible because they occur in the context of an economic boom. As local institutions central to communities, schools can provide an important lens for understanding the economic and demographic impacts of community change, such as boomtown development and the seemingly paradoxical creation of new forms of poverty and inequality in the midst of rapid localized economic expansion.

REFERENCES

Au, Wayne. 2010. “The Idiocy of Policy: The Anti-Democratic Curriculum.” Critical Education 1(1):1–16.

Barley, Zoe A., and Sandra Wegner. 2010. “An Examination of the Provision of Supplemental Educational Services in Nine Rural Schools.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 25(5):1–13.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2001. Liquid Modernity. New York: Wiley.

Berliner, David C. 2006. “Our Impoverished View of Educational Research.” Teachers College Record 108(6):949–95.

Biddle, Catharine. 2015. “Communities Discovering What They Care About: Youth and Adults Leading School Reform Together.” PhD dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

Biddle, Catharine, and Amy P. Azano. 2016. “Constructing the Rural School Problem: A Century of Rurality and Rural Education Research.” Review of Research in Education 40(1):298–325.

Biddle, Catharine, and Kai A. Schafft. 2016. “Educational and Ethical Dilemmas for STEM Education in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale Gasfield Communities.” In Reconceptualizing STEM Education: The Central Role of Practices, ed. Richard Duschl and Amber Bismack, 205–15. New York: Routledge.

Blank, Rebecca M. 2005. “Poverty, Policy, and Place: How Poverty and Policies to Alleviate Poverty Are Shaped by Local Characteristics.” International Regional Science Review 28(4):441–64.

Bouck, Emily C. 2004. “How Size and Setting Impact Education in Rural Schools.” The Rural Educator 25(3):38–42.

Brown, David L., and Kai A. Schafft. 2011. Rural People and Communities in the 21st Century: Resilience and Transformation. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Brownell, Mary T., Anne M. Bishop, and Paul T. Sindelar. 2005. “NCLB and the Demand for Highly Qualified Teachers: Challenges and Solutions for Rural Schools.” Rural Special Education Quarterly 24(1):9–15.

Budge, Kathleen. 2006. “Rural Leaders, Rural Places: Problem, Privilege, and Possibility.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 21(13):1–10.

——. 2010. “Why Shouldn’t Rural Kids Have It All? Place-Conscious Leadership in an Era of Extralocal Reform Policy.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 18(1):1–26.

Cancian, Maria, and Sheldon Danziger. 2009. “Changing Poverty and Changing Antipoverty Policies.” In Changing Poverty, Changing Policies, ed. Maria Cancian and Sheldon Danziger, 1–31. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cancian, Maria, and Deborah Reed. 2009. “Family Structure, Childbearing, and Parental Employment: Implications for the Level and Trend in Poverty.” In Changing Poverty, Changing Policies, ed. Maria Cancian and Sheldon Danziger, 92–121. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Carr, Patrick, and Maria Kefalas. 2009. Hollowing Out the Middle: The Rural Brain Drain and What It Means for America. Boston: Beacon Press.

Corbett, Michael. 2007. Learning to Leave: The Irony of Schooling in a Coastal Community. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Press.

——. 2015. “Rural Education: Some Sociological Provocations for the Field.” Australian and International Journal of Rural Education 25(3):9–25.

Corcoran, Mary. 2009. “Mobility, Persistence, and the Consequences of Poverty for Children: Child and Adult Outcomes.” In Understanding Poverty, ed. Sheldon H. Danziger and Robert H. Haveman, 127–161. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Corcoran, Sean P. 2010. “Can Teachers Be Evaluated by Their Students’ Test Scores? Should They Be? The Use of Value-Added Measures of Teacher Effectiveness in Policy and Practice.” Education Policy for Action Series. Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED522164.pdf.

Danziger, Sheldon H., and Robert Haveman. 2001. “Introduction: The Evolution of Poverty and Antipoverty Policy.” In Understanding Poverty, ed. Sheldon H. Danziger and Robert H. Haveman, 1–24. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dayton, John. 1998. “Rural School Funding Inequities: An Analysis of Legal, Political, and Fiscal Issues.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 14(3):142–48.

Duncan, Greg J., and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn. 2013. “Family Poverty, Welfare Reform, and Child Development.” Child Development 71(1):188–96.

Dutro, Elizabeth. 2010. “What ‘Hard Times’ Means: Mandated Curricula, Class-Privileged Assumptions, and the Lives of Poor Children.” Research in the Teaching of English 44(3):255–92.

Eppley, Karen. 2009. “Rural Schools and the Highly Qualified Teacher Provision of No Child Left Behind: A Critical Policy Analysis.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 24(4):1–11.

Ferguson, Ronald F. 2007. Toward Excellence with Equity: An Emerging Vision for Closing the Achievement Gap. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Gerstl-Pepin, C. I. 2006. “The Paradox of Poverty Narratives: Educators Struggling with Children Left Behind.” Educational Policy 20(1):143–62.

Gibbs, Robert M., and John B. Cromartie. 1994. “Rural Youth Outmigration: How Big Is the Problem and for Whom?” Rural Development Perspectives 10(1):9–16.

Goetz, Stephan J. 2005. “Random Variation in Student Performance by Class Size: Implications of NCLB in Rural Pennsylvania.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 20(13):1–8.

Goetz, Stephan J., and Hema Swaminathan. 2006. “Walmart and County-Wide Poverty.” Social Science Quarterly 87(2):211–26.

Guajardo, Francisco, Delia Pérez, Miguel A. Guajardo, Eric Dávila, Juan Ozuna, Maribel Saenz, and Nadia Casaperalta. 2006. “Youth Voice and the Llano Grande Center.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 9(4):359–62.

Hanson, Thomas L., Sara McLanahan, and Elizabeth Thomson. 1997. “Economic Resources, Parental Practices, and Children’s Well-Being.” In Consequences of Growing Up Poor, ed. Greg. J. Duncan and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, 190–238. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Toronto, Canada: Oxford University Press.

Hodge, C. Lynn, and Bernita L. Krumm. 2009. “NCLB: A Study of Its Effect on Rural Schools: School Administrators Rate Service Options for Students with Disabilities.” Rural Special Education Quarterly 28(1):20.

Howley, Aimee, and Craig B. Howley. 2005. “High-Quality Teaching: Providing for Rural Teachers’ Professional Development.” The Rural Educator 26(2):1–5.

Iceland, John. 2006. Poverty in America: A Handbook. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Irons, E. Jane, and Sandra Harris. 2007. The Challenges of No Child Left Behind. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

James, Alex, and David Aadland. 2011. “The Curse of Natural Resources: An Empirical Investigation of U.S. Counties.” Resource and Energy Economics 33:440–53.

Jennings, John F. 2001. “Title I: Its Legislative History and Promise.” In Title I: Compensatory Education at the Crossroads, ed. Geoffrey D. Borman, Samuel C. Stringfield, and Robert E. Slavin, 1–24. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Jimerson, Lorna. 2005a. “Special Challenges of the ‘No Child Left Behind’ Act for Rural Schools and Districts.” The Rural Educator 26(3):1–4.

——. 2005b. “Placism in NCLB—How Rural Children Are Left Behind.” Equity & Excellence in Education 38(3):211–19.

Jones, Nicola A., and Andy Sumner. 2011. Childhood Poverty, Evidence and Policy: Mainstreaming Children in International Development. Portland, OR: Policy Press.

Kaestle, Carl, and Marshall Smith. 1982. “The Federal Role in Elementary and Secondary Education, 1940–1980.” Harvard Educational Review 52(4):384–408.

Kelsey, Timothy, Willian Hartman, Kai A. Schafft, Yetkin Borlu, and Charles Costanzo. 2012. “Marcellus Shale Gas Development and Pennsylvania School Districts: What Are the Implications for School Expenditures and Tax Revenues?” Penn State Cooperative Extension Marcellus Education Fact Sheet.

Khattri, Nidhi, Kevin W. Riley, and Michael B. Kane. 1997. “Students at Risk in Poor, Rural Areas: A Review of the Research.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 13(2):79–100.

Killeen, Kieran, and Kai A. Schafft. 2015. “The Organizational and Fiscal Implications of Transient Student Populations in Urban and Rural Areas.” In Handbook of Research in Education Finance and Policy, ed. Helen F. Ladd and Edward B. Fiske, 623–63. New York: Routledge.

Korenman, Sanders, and Jane E. Miller. 1997. “Effects of Long-Term Poverty on Physical Health of Children in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth.” In Consequences of Growing Up Poor, ed. Greg. J. Duncan and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, 70–99. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Linn, Robert L., Eva L. Baker, and Damian W. Betebenner. 2002. “Accountability Systems: Implications of Requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001.” Educational Researcher 31(6):3–16.

Lipina, Sebastían J., and Jorge A. Colombo. 2007. Poverty and Brain Development During Childhood: An Approach from Cognitive Psychology and Neuroscience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ludwig, Jens, and Susan Mayer. 2006. “ ‘Culture’ and the Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty: The Prevention Paradox.” The Future of Children 16(2):175–96.

Lyson, Thom A. 2002. “What Does a School Mean to a Community? Assessing the Social and Economic Benefits of Schools to Rural Villages in New York.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 17(3):131–37.

Massey, Douglas S. 1996. “The Age of Extremes: Concentrated Affluence and Poverty in the Twenty-First Century.” Demography 33(4):395–412.

Matz, Jacob, and Daniel Renfrew. 2015. “Selling ‘Fracking’: Energy in Depth and the Marcellus Shale.” Environmental Communication 9(3):288–306.

McDonough, Patricia M., R. Evely Gildersleeve, and Karen M. Jarsky. 2010. “The Golden Cage of Rural College Access: How Higher Education Can Respond to the Rural Life.” In Rural Education for the Twenty-First Century: Identity, Place, and Community in a Globalizing World, ed. Kai A. Schafft and Alecia Youngblood-Jackson, 191–209. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

McGuinn, Patrick. 2011. “Stimulating Reform: Race to the Top, Competitive Grants and the Obama Education Agenda.” Educational Policy 26(1):136–59.

McLaughlin, Diane K., Carla Shoff, and Mary-Ann Demi. 2014. “Influence of Perceptions of Current and Future Community on Residential Aspirations of Rural Youth.” Rural Sociology, 79(4):453–77.

Mette, Ian. 2013. “Turnaround as Reform: Opportunity for Change or Neoliberal Posturing?” Interchange 43(4):317–42.

Noguera, Pedro. 2003. City Schools and the American Dream: Reclaiming the Promise of Public Education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Petrin, Robert A., Kai A. Schafft, and Judith L. Meece. 2014. “Educational Sorting and Residential Aspirations Among Rural High School Students: What Are the Contributions of Schools and Educators to Rural Brain Drain?” American Educational Research Journal 51(2):294–326.

Rank, Mark R., and Thomas A. Hirschl. 2002. “Welfare Use as a Life Course Event: Toward a New Understanding of the U.S. Safety Net.” Social Work 47(3):237–48.

Schafft, Kai A. 2010. “Conclusion: Economics, Community, and Rural Education: Rethinking the Nature of Accountability in the Twenty-First Century.” In Rural Education for the Twenty-First Century: Identity, Place, and Community in a Globalizing World, ed. Kai A. Schafft and Alecia Youngblood-Jackson, 275–289. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Schafft, Kai A., Theodore R. Alter, and Jeffrey C. Bridger. 2006. “Bringing the Community Along: A Case Study of a School District’s Information Technology Rural Development Initiative.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 21(8):1–10.

Schafft, Kai A., and Catharine Biddle. 2014. “School and Community Impacts of Hydraulic Fracturing Within Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale Region, and the Dilemmas of Educational Leadership in Gasfield Boomtowns.” Peabody Journal of Education 89(5):670–82.

——. 2015. “Opportunity, Ambivalence, and Youth Perspectives on Community Change in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale Region.” Human Organization, 74(1):74–85.

Schafft, Kai A., Leland Glenna, Brandn Green, and Yetkin Borlu. 2014. “Local Impacts of Unconventional Gas Development Within Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale Region: Gauging Boomtown Development Through the Perspectives of Educational Administrators.” Society & Natural Resources, 27(4):389–404.

Schafft, Kai A., Kieran Killeen, and John Morrissey. 2010. “The Challenges of Student Transiency for Rural Schools and Communities in the Era of No Child Left Behind.” In Rural Education for the Twenty-First Century: Identity, Place, and Community in a Globalizing World, ed. Kai A. Schafft and Alecia Youngblood-Jackson, 95–114. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Schlichte, Jacqueline, Nina Yssel, and John Merbler. 2005. “Pathways to Burnout: Case Studies in Teacher Isolation and Alienation.” Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth 50(1):35–40.

Sherman, Jennifer. 2009. Those Who Work, Those Who Don’t: Poverty, Morality, and Family in Rural America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

——. 2013. “Surviving the Great Recession: Growing Need and the Stigmatized Safety Net.” Social Problems, 60(4):409–32.

——. 2014. “Rural Poverty: The Great Recession, Rising Unemployment, and the Under-Utilized Safety Net.” In Rural America in a Globalizing World: Problems and Prospects for the 2010s, ed. Conner Bailey, Leif Jensen, and Elizabeth Ransom, 523–42. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

Sipple, John W., and Kieran Killeen. 2004. “Context, Capacity, and Concern: A District-Level Analysis of the Implementation of Standards-Based Reform in New York State.” Educational Policy 18(3):456–90.

Smith, Judith R., Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, and Pamela K. Klebanov. 1997. “Consequences of Living in Poverty for Young Children’s Cognitive and Verbal Ability and Early School Achievement.” In Consequences of Growing Up Poor, ed. Greg. J. Duncan and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, 132–89. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Snow-Gerono, Jennifer L. 2005. “Professional Development in a Culture of Inquiry: PDS Teachers Identify the Benefits of Professional Learning Communities.” Teaching and Teacher Education 21(3):241–56.

Strange, Marty. 2011. “Finding Fairness for Rural Students.” Phi Delta Kappan 92(6):8–15.

Sullivan, William M. 2011. “Interdependence in American Society and Commitment to the Common Good.” Applied Developmental Science 15(2):73–78.

Swanson, Jean. 2001. Poor-Bashing: The Politics of Exclusion. Toronto, Canada: Between the Lines.

Tickamyer, Ann R. 2006. “Rural Poverty.” In Handbook of Rural Studies, ed. Paul Cloke, Terry Marsden, and Patrick Mooney, 411–26. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Tyack, David B. 1972. “The Tribe and the Common School: Community Control in Rural Education.” American Quarterly 24(1):3–19.

Urry, John. 2005. “The Complexities of the Global.” Theory, Culture & Society 22(5):235–54.

Welner, Kevin Grant, and Wendy C. Chi. 2008. Current Issues in Education Policy and the Law. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Wilber, T. 2012. Under the Surface: Fracking, Fortunes, and the Fate of Marcellus Shale. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Wright, Christina. 2012. “Becoming to Remain: Community College Students and Postsecondary Pursuits in Central Appalachia.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 27(6):1–11.