Gary Paul Green

For several decades, policy makers have relied on economic growth as the principle strategy for alleviating poverty. Based on a premise that “a rising tide lifts all boats,” economic growth promises to create jobs, raise wages, and improve opportunities for the poor. Economic growth also has the capacity to unleash innovation and entrepreneurship, which can contribute to job and income growth as well. Proponents of the economic growth model have stressed the limited success of government programs in the past in reducing poverty (Murray 1984).

This emphasis on economic development stands in stark contrast to previous efforts to reduce poverty. Poverty programs in the United States have historically focused on providing social services such as housing, food, and child care to low-income families. At various times in history, religious organizations and nonprofit organizations have taken a lead role in these programs, but the responsibility has fallen largely to state and federal governments (O’Connor 1999). These programs provide low-income households with a social safety net that is critical to building opportunities for economic mobility.

This chapter examines two important questions relating to this transition from providing social services to promoting economic growth as the response to poverty. First, how effective is job growth in lifting workers out of poverty? Theoretically, job growth should reduce unemployment and poverty for a couple of reasons. New jobs can create opportunities for the unemployed and the poor. Competition for workers raises wages and improves opportunities for low-wage workers. Economic growth creates new markets that provide incentives for entrepreneurship, which opens new opportunities for low-wage workers. These benefits of economic growth, however, are dependent on several conditions that may not be met in many rural areas today. In addition, it should be recognized that policies promoting job growth tend to be individualistic in nature—they are not directed toward poor places. Workers are assumed to be mobile and will move to places where job growth is occurring.

The second question concerns whether community-based approaches to economic growth are any more effective than traditional economic development strategies (such as offering tax incentives and subsidies) in lowering unemployment and poverty rates and raising wages. For most rural communities, economic development strategies involve efforts to attract or retain businesses in the area. These place-based approaches can be distinguished from strategies that emphasize community-owned and controlled institutions. Community-based economic development attempts to minimize external control of the local economy and maximize the benefits for residents. A growing number of localities, for example, have created community development financial institutions, such as microenterprise loan funds or regional workforce development networks, to reduce unemployment and poverty. Although these activities promote economic development, community-based strategies have social objectives as well. A distinguishing characteristic is that they have mechanisms directed toward the poor and disadvantaged in specific places. In other words, it is not assumed that markets will reduce poverty and inequality without institutional change. By incorporating social goals, these strategies attempt to overcome some of the inherent weaknesses of markets in the fight against poverty.

This chapter examines the opportunities and limits of promoting economic growth as a means of fighting poverty with a focus on how the context in rural areas may limit the benefits of economic growth for the rural poor. Next, the potential and limits of community-based economic development approaches to alleviate rural poverty are assessed. Microenterprise loan funds are widely used to promote entrepreneurship as a pathway out of poverty. Workforce development programs attempt to prepare unemployed and disadvantaged workers for local jobs. Tourism is frequently touted as an effective way for rural communities to create new jobs. Finally, the potential and limits of these community-based development efforts in rural areas are examined.

THE EVOLUTION OF PLACE-BASED POVERTY PROGRAMS

Beginning in the progressive era, community practitioners attempted to counteract poverty by providing comprehensive approaches to social service delivery in neighborhoods. Progressives were concerned with the high rates of immigration and the resulting social disorganization found in urban areas. They believed the rapid rates of immigration at the turn of the twentieth century were contributing to the lack of social integration and urban social problems. The goal of community intervention was to better integrate the poor into the larger society and build a sense of collective efficacy rather than change the structural conditions that were creating the social problems. These efforts focused on providing child care, job training, and language programs to the poor through neighborhood organizations.

Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal shifted the emphasis on poverty alleviation to federal programs promoting home ownership and government-supported employment, such as the Works Progress Administration (Green and Haines 2015). Through a variety of direct relief programs, the federal government also provided stimulation to the economy. Policy makers recognized the weaknesses of local efforts to ameliorate the high rates of poverty and unemployment generated by the Great Depression. Although some critics have charged that the New Deal effectively squashed social unrest and protected the interests of the capitalist class, there is agreement that it established a social safety net for the poor, especially among the elderly, through the establishment of the Social Security program in 1935 (Piven and Cloward 1971). The New Deal programs were directed at individuals, but the social welfare programs were implemented at the local level. This decision to implement social policy through poor places reflected the political reality that the administration needed the support of southern Democrats to pass much of the New Deal legislation (Green and Haines 2015).

Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty placed more emphasis on local control and public participation in poverty programs. The Community Action Program (CAP), for example, required the “maximum feasible participation” of residents in designing and implementing programs affecting their area (Moynihan 1969). In addition, CAP allocated resources to nonprofit organizations in communities to provide job training and social services. Local officials were opposed to these programs because they were unable to control how these resources were used. Although the War on Poverty has been criticized for failing to eliminate poverty, it did introduce innovative strategies for engaging the public in poverty programs and made important advancements in reducing poverty.

The Clinton administration used federal tax incentives and grants to improve the business climate in selected poor neighborhoods and communities. The Empowerment Zones/Enterprise Community (EZ/EC) initiative, however, also provided support for job training, child care, and transportation to assist residents seeking jobs. This initiative, originally proposed under the Reagan administration, directly linked improvements in the business climate with poverty reduction in impoverished neighborhoods and communities. Although it prioritized economic development in places, it also provided important social services (and job training) to poor communities. Evaluations of the effectiveness of the EZ/EC initiatives, however, suggest they had mixed effects (Pitcoff 2000).

One of the Obama administration’s key place-based poverty programs, the Promise Zone initiative, was modeled after a program in Harlem that provides a wide range of services that focus on the well-being of children. It went beyond the tax incentive programs established by the Clinton administration. The program provided funds for neighborhood revitalization, especially street lighting and removing abandoned buildings. In addition, the programs focused on support for pre-K and early college programs. Each location had a plan for development that is supported with tax breaks for businesses, job training, AmeriCorps volunteers, and improved service provision.

This brief review points to the evolution of place-based poverty programs from service provision to economic development. The idea that economic development is the best tool to fight poverty has become firmly entrenched in federal, state, and local policy. This transformation is part of the broader resurgence of neoliberalism (Harvey 2005). Neoliberal strategies typically involve cutting government expenditures and using market mechanisms to solve social, economic, and environmental problems. There continues to be considerable debate, however, on whether these strategies can adequately address inequality and poverty (Blank 1997). Conversely, many analysts also doubt that place-based economic development approaches are the appropriate mechanism for addressing poverty (Dreier 2015; Lemann 1994).

As state and local governmental deficits have increased over the past few decades and many regions have suffered relatively high long-term unemployment rates, municipalities have intensified their efforts by providing economic development incentives as a means of increasing government revenues, jobs, and income as well as reducing poverty and unemployment. The next section briefly reviews the literature on the opportunities and limits of economic development as a strategy for reducing rural poverty.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS OF THE ECONOMIC GROWTH MODEL

Economic theory suggests that demand-side labor market policies have a potential to reduce poverty and unemployment, primarily through job creation and competition for workers. Some of the underlying assumptions of the economic growth model are examined next, and weaknesses of this theory when applied to addressing poverty, especially in rural areas, are evaluated.

Per economic theory, localities are in competition with each other to attract capital and people. Local governments are assumed to be rational actors that pursue economic development for the benefit of the entire community (Ramsay 1996). Federalism deters localities from redistributive policies and assumes that they can be more efficiently administered at the state and national levels (Peterson 1981).

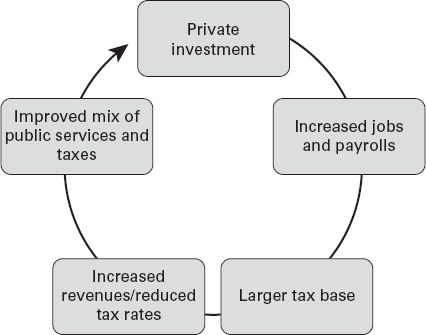

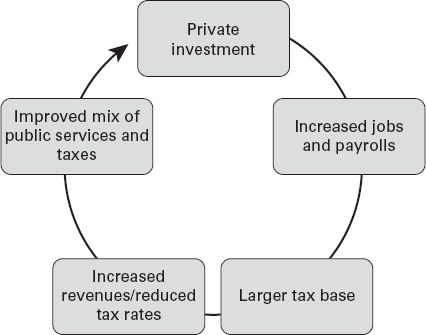

Another assumption underlying the economic growth model is that businesses and residents are perfectly mobile and will choose to locate in places that offer them their preferred mix of services and taxes. Localities that attract new residents or businesses increase government revenue, which allows them to provide more services or reduce taxes. In addition, job growth provides new opportunities for the poor and the underemployed. Even if employed workers take many of the jobs that are created, unemployed workers in the region benefit from old jobs that open. In addition, job growth theoretically generates competition among employers for workers. This competition should lead to wage growth, which also can pull the working poor out of poverty. If localities lose businesses or population, they must raise taxes to maintain the existing level of services. This process of raising taxes can lead to more population and business losses, and the poor and unemployed are left with fewer job opportunities. The economic growth model is depicted in figure 15.1.

Figure 15.1 The economic growth model.

Government policies promoting economic development rely heavily on tax breaks, subsidies, and other incentives to attract businesses or to retain them in the locality. Much of the debate regarding these policies concerns whether these incentives are necessary to influence business location decisions. One critique is that subsidies have little or no influence on business location decisions. Research suggests that factors such as proximity to markets and labor productivity are much more important than taxes and other incentives in business location or expansion decisions (Green, Fleischmann, and Kwong 1996; Lobao, Jeanty, Partridge, and Kraybill 2012). Thus, many businesses receive tax breaks when they would have located in the area without them.

One important factor influencing the relationship between economic growth and poverty is how local governments fund their economic development activities. If local governments reduce expenditures for education and social services to provide incentives for businesses, residents and businesses may migrate to other places (Bartik 1991). Thus, this strategy may have negative consequences for low-income and unemployed workers. For example, many communities use tax increment financing (TIF), which freezes taxes on businesses that expand or locate in a specific area. These programs often have a negative impact on schools and other services that are funded primarily through property taxes (Hicks, Faulk, and Quinn 2015).

It is also important to consider the net benefits and costs of economic development incentives (Green et al. 1996). As competition for jobs has increased over the past few decades, rural communities are offering more incentives to attract new firms. There is concern in many communities that this hypercompetition for capital has resulted in more costs than benefits. The jobs created do not make up for the lost government revenue and the decline in social services for the poor.

Research on the effects of job growth on local unemployment is somewhat mixed. In one of the most frequently cited studies on the benefits of tax breaks on unemployment, Bartik (1991) estimates that a state and local business tax reduction of 10 percent would increase business activity in an area by 2.5 percent. Increased business activity results in more job opportunities and ultimately lowers the unemployment rate. Bartik (1991) concluded that a 1 percent increase in local employment reduced the long-run local unemployment rate by 0.1 percent and raised the labor force participation rate by 0.1 percent. This analysis of urban areas suggests that the net benefits are greater than the costs for most economic development policies. More recent evidence suggests that job growth may have a stronger impact in rural counties with high rates of poverty (Partridge and Rickman 2005; Partridge, Rickman, and Li 2009).

Other studies have found a limited impact of economic growth on poverty or unemployment because growth redistributes rather than creates jobs (Logan and Molotch 1987). In other words, job growth in one region comes at the expense of jobs in other regions. Although local poverty rates may decline locally, the aggregate poverty rate does not change.

Even at the local level, economic growth may have a negligible effect on unemployment and poverty. Summers et al. (1976) reviewed the research on new plant locations in small towns and concluded that on average previously unemployed workers take fewer than 10 percent of jobs created in these settings. In-migrants or workers who already have jobs take most of the new jobs that are created. Many of the job vacancies may be filled by workers willing to commute long distances and are not interested in moving closer to their job. Hout, Levanon, and Cumberworth (2011) also found that employers are reluctant to hire long-term unemployed workers because of perceived outdated skills, which means they do not employ local workers who have been unemployed for a long period. In a more recent analysis on this issue, however, Betz and Partridge (2012) found that migration over the past fifteen years has been less responsive to employment opportunities in rural areas. This would suggest that local unemployed and low-income workers would benefit from job creation.

Economic growth may fail to generate benefits for the unemployed or poor because of a skills mismatch (Gibbs, Swaim, and Teixeira 1998). A skills mismatch can occur when the skills demanded by employers do not match well with the skills of workers in the area (Kain 1992). Lack of transportation may limit the ability of job seekers to find and obtain available jobs. In urban areas, racial residential segregation is a major contributor to the spatial mismatch between the inner city and suburbs. Most of the unemployed and poor live in the inner city, but they do not have access to the jobs being created in the suburbs. In rural areas, residential segregation is less the issue, but commuting distances and lack of public transportation may present obstacles for job seekers.

Second, job seekers may lack the skills required by local employers. Economic development efforts, for example, may successfully attract employers to the region, but the new jobs do not match the skills available in the local workforce. Or the skills demanded by employers may be changing more rapidly than the workforce’s skills due to technological advancements. On average, rural residents have lower levels of human capital (e.g., education and job training) than do urban residents (Lichter, Beaulieu, Findeis, and Teixeira 1993; Marre 2015). Often job openings for skilled workers remain unfilled. Employers also discuss the lack of “soft” skills among workers as a serious obstacle to hiring workers (Moss and Tilly 2003). Examples of soft skills might include the ability to work in teams or interpersonal skills required to deal with customers.

Finally, training and educational institutions may not be preparing workers for the types of jobs available in the region. Training programs require enough students to efficiently offer an educational or training setting. Equipment necessary for training may require a scale that is not available in many rural areas. The response by workers in many rural communities is to migrate to urban areas where they may be able to get a better return on their investment in education and training.

Economic growth potentially creates job openings for low-income and unemployed workers and places pressure on employers to raise wages. In practice, however, there are many institutional reasons these policies may have a limited impact on poverty and unemployment. Firms in industries with global markets face pressures to keep wages to a minimum. The lack of unions in most rural areas also reduces the bargaining power of workers in these settings.

The empirical evidence suggests that labor demand policies can potentially overcome some of these obstacles by more carefully targeting resources to workers and employers (Bartik 2001). First, subsidies to employers should focus on hiring unemployed workers in the local labor market. Many communities have adopted “first source” incentives to ensure that jobs created through subsidies first benefit local workers who need jobs. Often these incentives will require that new positions be created to satisfy the requirement.

Second, to be effective, subsidies should be targeted to areas with high unemployment rates. Many states offer incentives to businesses to locate anywhere in the state. Typically, these businesses will not locate in areas with high unemployment.

Third, subsidies may more effectively reduce unemployment and poverty if they are directed to small businesses and nonprofit agencies. These employers tend to be less mobile than corporations recruited to the area and may generate more long-term benefits for low-income and unemployed workers (Brown, Hamilton, and Medoff 1990).

COMMUNITY-BASED ANTIPOVERTY PROGRAMS

Rural communities have relied heavily on the traditional tools of economic development, such as industrial recruitment activities, to create demand for workers. There is growing concern that these efforts are largely ineffective for most communities. Thus, many economic development practitioners in rural areas have turned to alternative strategies. Community development financial institutions, for example, direct financial resources to communities or borrowers who may have difficulty gaining access to loans from traditional institutions. Workforce development programs focus on preparing unemployed workers for the labor force. As extractive industries have declined in many rural areas, economic development efforts have turned to amenity-based development to promote job opportunities. These projects focus directly on ensuring that the poor will benefit from the economic development activity. Some of the strengths and weaknesses of each of these approaches are addressed in the following sections.

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

Rural businesses and residents often lack access to financial capital. They suffer from disinvestment as traditional financial institutions reinvest local assets to other more profitable or less risky locations. There may be several reasons for capital markets to operate in this manner in rural areas (Green and Haines 2015). First, rural credit markets tend to lack competition. For example, small towns typically cannot support more than one or two banks. With little or no competition, financial institutions face less pressure to serve the needs of the community (especially low-income residents) or to take more risk.

Second, financial institutions often lack adequate information about loan applicants. Financial institutions tend to rely on signals that do not necessarily reflect the risk of the applicant. With inadequate information, lenders tend to take less risk. This can be especially disadvantageous for rural borrowers because the loan decisions are increasingly made in urban areas. Removing the decision making from rural communities means that lenders have even less informal information about applicants and will take less risk.

Third, there continues to be concern that financial institutions may discriminate against minority and women applicants. Rejection rates are much higher for minorities and women than for other loan applicants (Squires and O’Connor 2001). There are fewer alternative sources of credit for women and minorities in rural areas.

In response to these limitations in rural credit markets, several localities have created community development financial institutions (CDFIs) designed to improve access to credit for women, minorities, and the poor. These institutions build assets that can be used for education, home ownership, or small business development (Sherraden 1991). The most common loan funds are microenterprise loan funds, community development credit unions, and community development banks. These institutions do not focus exclusively on profits but inject a social element into their decision-making processes as well. In this regard, CDFIs’ financial assets are not treated strictly as commodities, so they will be available to residents.

MICROENTERPRISE LOAN FUNDS

Microenterprise loan funds are designed to address the difficulties entrepreneurs and small businesses face in gaining access to debt capital. These businesses seldom borrow from traditional banks and lending institutions. Microenterprise loan funds especially promote entrepreneurship among women and minorities who face more obstacles in rural labor markets (Tigges and Green 1994). Although the amount varies, microenterprise loan funds make very small loans to purchase equipment or supplies for a business, such as a sewing machine to start a dressmaking business or a snow blower to begin a snow removal service.

Some microenterprise loan funds have adopted the principles used by the Bangladeshi Grameen Bank. The Grameen Bank is famous for peer group lending practices that make loans to small groups of women (five to eight members) and then rotate the loan around to different members when it is repaid. This practice establishes peer pressure to repay loans and helps to provide social support to entrepreneurs. The Grameen Bank has a loan loss rate of approximately 2 percent, which is extremely low for a loan fund (“Grameen Bank at a Glance” 2015).

One example of a successful rural microenterprise loan fund is the Four Bands Community Fund on the Cheyenne River Reservation in rural western South Dakota (Dewees and Sarkozy-Banozczy 2010). The 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization provides small business loans. Applicants must complete business training and may receive technical assistance for their businesses. The education and training that are required are essential pieces to the success of these funds and to poverty alleviation on reservations. By providing alternative sources of funding, the poor and unemployed find alternatives to wage employment in these poor rural areas.

Rural microenterprise loan funds face several constraints. Most funds are not large enough to become self-sustaining, so they must rely on foundations and governments to continually fund their activities. It is much easier to achieve the necessary scale and become self-sustaining in urban areas where there is a higher density of borrowers. Few recipients of microloans graduate to commercial banks, so the borrowers remain dependent on microenterprise loan funds (Dewees and Sarkozy-Banozczy 2010). This pattern limits the ability of microenterprise loan funds to reach additional entrepreneurs and have a broader impact on rural development (Green and Haines 2015).

Regulations or public policies also can create obstacles for microenterprise loan funds. In many states, entrepreneurial earnings count against income limits for receiving public aid. This means that entrepreneurs risk losing their aid, such as health care, if they earn too much from their business. In addition, entrepreneurs frequently must obtain a business license, which can be a difficult obstacle to overcome for a newly established business. Health regulations can serve as a major obstacle for microenterprises, especially for those in the food industry. Requiring businesses to meet industry standards for production may prove to be too costly for many small businesses and farms.

Overall, there is a great deal of potential with microenterprise loan funds in rural development. They are constrained, however, by the low density of borrowers in most rural areas. Relatively few of these microenterprises expand to employ additional workers, which may limit their impact on poverty. Developing loan funds across a broader region may be an effective way to overcome the limits of population density in rural areas. Overall, microenterprise loan funds offer an alternative for many rural poor people who have very little access to traditional financial institutions (Ager 2014).

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CREDIT UNIONS

Community development credit unions (CDCUs) operate like other credit unions, except they have a geographic or associational bond in areas where most members are low-income residents. There are approximately 400 CDCUs in the United States. These institutions limit their investments to local areas where their customers live.

An example of a CDCU is the Lac Courte Oreilles Federal Credit Union (LCOFCU) located in Hayward, Wisconsin (Dewees and Sarkozy-Banoczy 2010). The LCOFCU offers a wide variety of financial products, including savings accounts and loans. Credit products are offered only to tribal members as alternatives to predatory lending institutions in the area. In addition to the lending programs, the LCOFCU provides financial education classes and credit counseling to borrowers. The credit union features several loan programs that improve access to credit for borrowers who may not have much collateral or have a poor credit history.

In most cases, CDCUs operate as intermediaries between low-income borrowers and social investors. Social investors are interested in supporting efforts to improve access to capital in areas that have limited access to conventional sources of capital. Thus, they tend to be more limited in their operations and are dependent on the social investment funds for resources. Most CDCUs are in urban areas where there is a higher density of potential borrowers than in rural areas. CDCUs typically provide small consumer loans and small business loans.

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT BANKS

Like other CDFIs, community development banks serve as an intermediary between social investors (such as foundations and individuals) and poor neighborhoods and communities. These banks, however, tend to focus on housing loans, although some also do a substantial amount of lending to businesses.

One of the most touted community development banks was the Southern Development Bancorporation, which was located in rural Arkansas. This bank was modeled after the successful South Shore Bank in Chicago (Taub 1988). The bank became engaged in a wide variety of activities beyond lending. Much of their activity was related to development efforts in the Delta region, which has had historically high poverty rates.

Community development banks have had limited success (Taub 1988). The lack of social investment funds supporting them has been a major limitation. It may be easier to see the reasonable returns on investing in housing in urban areas where there may be more of a market. It may be more difficult to do this type of housing development in rural areas because of the low demand.

Overall, community development financial institutions address many of the weaknesses of rural credit markets and focus on the social needs of rural communities. These institutions direct assets to low-income residents who may be locked out of the conventional financial system. It is safe to say that CDFIs have been more successful in urban areas because of the scale and population density available in urban settings. Businesses relying on these sources of credit still face other structural disadvantages that these institutions cannot address.

One of the major limitations of CDFIs is that most are unable to become self-sufficient and therefore rely on foundations and social investors for continual financial support. This dependence has two important consequences. First, it means that funds are limited and do not come close to being able to fully address the problem of rural poverty. Second, dependence on external sources of finance may constrain the efforts of these institutions to address a broad set of needs in poor communities and to challenge the local power structure (Stoecker 1997). Dependency on external sources of funding, therefore, may constrain the activities of advocacy groups, especially their community organizing efforts.

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

Over the last few decades, practitioners and policy makers have recognized that workforce development is integral to economic development. Workforce development is more than just job training, however. It involves a wide range of activities from orientation to the work world to placement, as well as mentoring and follow-up counseling and crisis intervention. This approach to job training tends to be more holistic than most government training programs, and it provides a stronger linkage to local employers.

One of the primary reasons workforce development has been emphasized in rural areas is the persistent gap in educational attainment between urban and rural areas. Part of the gap can be explained by the demographic differences between rural and urban populations: rural areas have a much older population, and these workers tend to have less education (Beaulieu and Mulkey 1995). The gap in education, however, persists for even younger workers. Rural schools often lack the resources available in urban areas. In addition, the returns on investment in education and training are lower in rural than in urban areas (Gibbs et al. 1998). This means there is less of an incentive for rural residents to invest in additional education and training.

A second reason for the rise in interest in workforce development is because rural employers provide very little job training (Green 2007). Rural employers tend to demand a less-skilled workforce, which is reflected in the lower wages in the workforce. Manufacturing jobs in rural areas tend to demand more routine skills that do not require much education or specific job training (Green 2007).

Workforce development networks are intended to overcome some of the weaknesses inherent in rural labor markets. First, workforce development networks address one of the key issues facing low-wage workers—job information (Holzer 1996). Most unemployed and low-wage workers rely primarily on family and friends for information about available jobs. In addition, most workers find jobs through family or friends that are employed by the firm that is hiring them. One of the problems with these informal channels of information is that job seekers are disadvantaged (in terms of wages and benefits) compared to those who use more formal channels. This is especially the case for minority job seekers (Green, Tigges, and Diaz 1999). Workforce development networks provide more formal sources of information for low-wage and unemployed workers, which improves their likelihood of finding good jobs.

Second, workforce development networks provide a stronger linkage between workers’ skills and those demanded by local employers. This is one of the key differences between workforce development networks and government job training programs that have been administered in the past. Government programs are not strongly tied to local demand. Research suggests that the types of jobs most available to poor and unemployed workers tend to require “soft” skills rather than extensive math or reading skills (Bartik 2001). This is especially true for jobs that require interaction with customers or coworkers. Workforce development networks often promote training programs that build these types of skills through direct interaction with employers.

Third, workforce development networks also address some of the obstacles to employer-provided training. Employers are often reluctant to provide training to workers because they fear they will lose their investment when a worker takes a job elsewhere. It is in the interest of most employers to provide job training to increase productivity, but it is not in the interest of individual employers to take the risk of training workers and losing them to other employers. Workforce development networks address this collective action problem by bringing together employers with common training needs. By collaborating, employers overcome their collective action problem and generate a sufficient scale to efficiently provide training programs. One example is the plastics industry in central Wisconsin, which identified some common training needs and worked with the technical colleges and high schools to provide the training (Green 2007).

Finally, workforce development networks may provide workers with increased opportunities for occupational mobility. In many instances, employers provide few opportunities for workers to move up within their firm because they recruit workers with more advanced skills outside the firm. The result is higher turnover rates among low-skilled workers. In addition, employers may face difficulty in finding qualified workers. Workforce development networks can address these problems by establishing career ladders within a region. Low-skilled workers are encouraged to stay with their employer to receive additional job training. After they receive the training, they can obtain better paying jobs with employers participating in the network. This arrangement benefits low-wage employers because they can reduce their turnover rate and retain workers for a longer period. Employers demanding more skilled workers benefit because they gain access to this skilled workforce in the region. Employees benefit because they obtain additional training while holding onto their job (Mitnik and Zeidenberg 2007).

These workforce development networks can be established in several different ways in rural areas, and each has its own advantages and disadvantages (Harrison and Weiss 1998). In some cases, a single community-based organization is responsible for providing social services, job training, placement, and counseling. PathStone is an example of a sole provider model that provides workforce development services for immigrants in rural New York. This model has the advantage of providing a holistic approach to address the needs of low-income workers. In addition to job training, it provides clothing, transportation, and health care to migrant workers.

A more common way of organizing workforce development networks is to establish industrial clusters. Firms in the same industry can organize training and apprenticeship programs with educational institutions in a region. The advantage of the clusters is that they can identify common needs and build apprenticeship and training programs with educational institutions. One example is the 2+2+2 program established through the Wisconsin Plastics Valley Association. The foundation of the program is a plastics youth apprenticeship program for high school students in the region. After graduating, credits can be applied toward an associate’s degree with one of the regional technical colleges. This degree prepares students for the more skilled positions in the plastics industry. Finally, workers can transition to a bachelor’s degree program at the University of Wisconsin-Stout or the University of Wisconsin-Platteville to pursue a degree in engineering that focuses on plastics industry technology (Green 2007).

A third model is the hub-spoke employment training networks with a community-based organization as the central node linking employers, local governments, and training institutions. One example of a hub-spoke training network is the Mid-Delta Workforce Alliance, which has been operating in several rural counties in Mississippi and Arkansas since 1994. The alliance focuses primarily on providing workforce development services for low-skilled employees. The alliance identifies and mobilizes workforce development resources and establishes collaborative efforts at the local level. It has been actively involved in job shadowing programs, school-to-work programs, and other activities designed to improve job training in the region (Green 2007).

Although workforce development programs address some of the limitations in labor markets, it is difficult to overcome the structural weaknesses in rural labor markets. Workforce development primarily influences the supply side of the labor market while largely ignoring the demand side. Examples of demand-side policies include public employment programs or incentives (e.g., tax credits) for employers to hire disadvantaged workers. Bartik’s (2001) review of the empirical literature on demand-side policies suggests that these programs may have a stronger effect on hiring disadvantaged workers than do supply-side approaches. Demand-side approaches, however, are seldom used in the United States (especially in rural areas). Supply-side approaches are more consistent with the broader cultural values of American individualism. Ideally, labor market policies would incorporate both demand- and supply-side elements.

The lack of job opportunities in rural areas contributes to the “brain drain” from which so many rural communities suffer. Firms located in rural areas tend to be late in the profit/product cycle, which means that the industries have routinized production and have less need for skilled workers. Similarly, rural labor markets are often “thin,” which means that there are few jobs in each occupational category. These structural characteristics have the effect of reducing the competition for workers in these jobs and depressing wage levels (Green 2012). It is difficult for workforce development efforts to counter these structural obstacles in rural areas.

Finally, rural labor markets often lack intermediaries, such as unions, that improve wages and benefits. Unions have been shown to have a positive effect on wages and benefits (Mischel 2012). The low population density is probably the major reason for the lack of intermediaries.

AMENITY-BASED DEVELOPMENT AND TOURISM

Rural economies have historically been dependent on the extraction of natural resources, such as agriculture, forestry, mining, and fishing. Technological advancements and structural changes in extractive industries have reduced employment in these industries. In the 1960s and 1970s, low-wage manufacturing facilities moved into rural areas (Summers et al. 1976). Globalization and technological changes have contributed to the loss of manufacturing jobs in many rural areas, especially in those industries that face competition from developing countries.

Today, the service sector accounts for a growing proportion of jobs in rural areas. One of the major growth areas in the service sector is the expansion of tourism, recreation, and retirement opportunities in rural areas. In many rural communities, retirement income has become the economic base for these localities (Bishop and Gallardo 2011). This shift in the economic base of rural communities signifies a transformation from viewing natural resources as commodities to be extracted for external markets to a source of consumption for tourism, recreation, and retirement (Power 1988). Natural amenities have been shown to be a major factor in rural population change (Hunter, Boardman, and Saint Onge 2005; McGranahan 1999). Promotion of tourism is often used to address income inequality and poverty in rural communities, especially pro-poor tourism (Deller 2010; Scheyvens 2011). Jobs in the tourism industry typically do not require much training and can provide opportunities for workers with little job experience (Reeder and Brown 2005).

Amenity-based development efforts in rural areas face several obstacles. Natural amenities are highly income elastic, which means that high-income residents are willing to pay a higher price for living in the area. High-amenity regions tend to be less affordable, especially in terms of housing, for low-income residents. Low-income workers must commute long distances to work in these communities. Amenity-based development can produce a form of rural gentrification. Although this strategy generates new jobs, it may be more difficult for the poor to live in the community because of changes in the housing market. Local strategies are needed to ensure that affordable housing is available in these markets.

Jobs in the tourism and recreation industries tend to provide low wages, few benefits, and limited opportunities for economic mobility (Marcouiller, Kim, and Deller 2004). Many of the jobs in these industries are part-time or seasonal. Like most other industries in the service sector, tourism development tends to generate more income inequality in rural areas (Marcouiller et al. 2004).

There also is evidence that tourism-dependent communities often face more fiscal stress (Keith, Fawson, and Chang 1996). The high level of fiscal stress is probably because many of the natural amenities that draw tourists are public goods—they are available to everyone—but only residents must maintain them. Local governments may find that the costs exceed the benefits in supporting these amenities. One of the results is that social services may be limited, and the poor may have access to fewer resources.

Overall, amenity-based development, especially tourism, is the basis for economic development in many rural areas today. Tourism has become one of the largest industries in the world. A basic contradiction in amenity-based development is that job and population growth may destroy the key to economic development—the quality of the environment. Especially in areas with a fragile environment, any population or employment growth can threaten the natural amenities that are so attractive. Ironically, it typically is the recent migrants, rather than long-term residents, in rural areas who are often more supportive of more restrictive land use and environmental policies.

Finally, this discussion has suggested that there is often a tension between extraction activities and amenity-based development in resource-dependent communities. Over the past decade, many rural areas have experienced a boom, especially in gas shale development, that has generated many new jobs (Mason, Muehlenbachs, and Olmstead 2015). These regions have experienced significant population and income growth. One of the concerns about economic booms in resource-rich regions is that exports of resources may have a negative effect on the rest of the economy (what is referred to as the Dutch disease). The poor may benefit from some of the jobs created through extractive activities, but the costs of labor and other factors of production may drive out other economic activity that may benefit the poor. In addition, mining activities generally last for a relatively short period and leave regions dependent on these resources in a worse position once the resources are depleted (Power 1988). It is possible to balance extractive activities with amenity-based development, but it is a delicate equilibrium to maintain.

CONCLUSIONS

Rural areas continue to suffer from some basic structural features that constrain the ability of economic development efforts to reduce poverty. In some regions, rural communities continue to be dependent on a few industries, especially the extractive sector. This sector is extremely vulnerable to major shifts in markets and to new technology. Rural regions are often at a competitive disadvantage in the global market. For the past two decades, rural population growth has significantly lagged growth in urban areas (Kusmin 2014). Without major investments by federal and state governments in basic services, such as education and health care, population and jobs will concentrate in urban areas. This situation may leave behind the most disadvantaged rural residents who are less mobile.

Some of the primary community-based strategies that rural communities have employed to promote more opportunities for the poor have been described. It is doubtful that community-based antipoverty approaches will ever be able to overcome the structural forces facing disadvantaged communities. Yet these efforts are more likely to increase the participation of the poor in decisions affecting their community and yield significant benefits to residents.

An underlying issue to consider is whether economic development strategies that are ultimately based on job growth can ever be an effective approach to address poverty. Some analysts believe that neoliberal strategies are the fundamental cause of inequality and poverty, which makes them illogical choices as antipoverty mechanisms.

There are two important responses to this criticism of neoliberalism. First, these critiques assume that government programs are the only alternative for progressive change. There appears, however, to be very little public support for increasing the role of government, especially for programs related to rural poverty. The proportion of the population in rural areas continues to decline, and there is very little political support to shift resources to these issues.

Second, the key to many community-based economic development strategies is that they combine the profit motive with social objectives. The goal is not to maximize profits at all costs but to achieve social goals as well. Community development financial institutions are especially illustrative there. They must turn a profit to survive (and to provide resources to other residents), but they attempt to do this while serving local, low-income residents. These models usually do not have the resources to address all the need in rural areas. Foundations, social investment funds, and government resources are needed to expand these alternatives in rural areas.

This discussion about the limits of economic development as a strategy to reduce rural poverty raises some larger issues about the future of rural areas. Some economists have argued that the poor in rural areas choose to live in these communities and are making a trade-off between wages and noneconomic benefits to live in a rural community (e.g., easier access to outdoor recreation) (see Roback 1988). This argument implies that poverty is a choice rather than a consequence of social processes. It ignores the fact that poverty is often intergenerational and that children in poor families are more constrained in their choices (Sharkey 2013). It ultimately means that we need to find ways of providing a stronger safety net across rural areas to ensure that rural residents have the same choices urban residents have.

Finally, much of the discussion surrounding economic development and poverty focuses on job creation. We need to remember that many of the rural poor are underemployed (Young 2012). Additional low-wage jobs may have little or no effect on moving people out of poverty. Policies designed to address the issue of working poverty in rural areas must focus simultaneously on the supply and the demand side of local labor markets. These policies must focus on new pathways for building the high road in rural areas.

REFERENCES

Ager, Caplan M. 2014. “Communities Respond to Predatory Lending.” Social Work 59:149–56.

Bartik, Timothy J. 1991. Who Benefits from State and Local Economic Development Policies? Kalamazoo, MI: W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

——. 2001. Jobs for the Poor: Can Labor Demand Policies Help? New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Beaulieu, Lionel J., and David Mulkey. 1995. Investing in People: The Human Capital Needs of Rural America. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Betz, Michael, and Mark Partridge. 2012. “Country Road Take Me Home: Migration Patterns in Appalachian America and Place-Based Policies.” International Regional Science Review 36:267–95.

Blank, Rebecca. 1997. “Why Has Economic Growth Been Such an Ineffective Tool Against Poverty in Recent Years?” In Poverty and Inequality: The Political Economics of Redistribution, ed. J. Neill, 27–41. Kalamazoo, MI: W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment.

Brown, Charles, James Hamilton, and James Medoff. 1990. Employers Large and Small. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Deller, Steven. 2010. “Rural Poverty, Tourism, and Spatial Heterogeneity.” Annals of Tourism Research 37:180–205.

Dewees, Sarah, and Stewart Sarkozy-Banoczy. 2010. “Investing in the Double Bottom Line: Growing Financial Institutions in Native Communities.” In Mobilizing Communities: Asset Building as a Community Development Strategy, ed. Gary Paul Green and Ann Goetting, 14–47. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Gibbs, Robert M., Paul L. Swaim, and Ruy Teixeira, eds. 1998. Rural Education and Training in the New Economy: The Myth of the Rural Skills Gap. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press.

Green, Gary Paul. 2007. Workforce Development Networks in Rural Areas: Building the High Road. Cheltenham, United Kingdom, and Northhampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

——. 2012. “Rural Jobs: Making a Living in the Countryside.” In International Handbook of Rural Demography, ed. Laszlo Kulcsar and Katherine Curtis, 307–18. New York, NY: Springer.

Green, Gary P., Arnold Fleischmann, and Tsz Man Kwong. 1996. “The Effectiveness of Local Economic Development Policies in the 1980s.” Social Science Quarterly 77:609–25.

Green, Gary Paul, and Anna Haines. 2015. Asset Building and Community Development, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Green, Gary Paul, Leann M. Tigges, and Daniel Diaz. 1999. “Racial and Ethnic Differences in Job Search Strategies in Atlanta, Boston and Los Angeles.” Social Science Quarterly 80:263–78.

Harrison, Bennett, and Marcus Weiss. 1998. Workforce Development Networks: Community-Based Organizations and Regional Alliances. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hicks, Michael, Dagney Faulk, and Pam Quirin. 2015. Some Effects of Tax Increment Financing in Indiana. Muncie, IN: Center for Business and Economic Research, Ball State University.

Holzer, Harry. 1996. What Employers Want: Job Prospects for Less-Educated Workers. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hout, Michael, Asaf Levanon, and Erin Cumberworth. 2011. “Job Loss and Unemployment.” In The Great Recession, ed. David B. Brusky, Bruce Western, and Christopher Wimer, 59–81. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hunter, Lori, Jason Boardman, and Jarron Saint Onge. 2005. “The Association Between Natural Amenities, Rural Population Growth, and Long-Term Residents’ Economic Well-Being.” Rural Sociology 70:452–69.

Kain, John. 1992. “The Spatial Mismatch Hypothesis Three Decades Later.” Housing Policy Debate 3:371–92.

Keith, John, Christopher Fawson, and Tsangyao Chang. 1996. “Recreation as an Economic Development Strategy: Some Evidence from Utah.” Journal of Leisure Research 28:96–107.

Kusmin, Lorin. 2014. “Rural America at a Glance.” Economic Brief EB-26. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Lemann, Nicholas. 1994. “The Myth of Community Development.” New York Times, January 9.

Lichter, Daniel, Lionel J. Beaulieu, Jill Findeis, and Ruy Teixeira. 1993. “Human Capital, Labor Supply, and Poverty in Rural America.” In Persistent Poverty in Rural America, ed. Rural Sociological Society Task Force on Persistent Rural Poverty, 39–67. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Lobao, Linda, P. Wilmer Jeanty, Mark Partridge, and David Kraybill. 2012. “Poverty and Place Across the United States: Do County Governments Matter to the Distribution of Economic Disparities.” International Regional Science Review 35:158–87.

Logan, John R., and Harvey L. Molotch. 1987. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Marcouiller, David W., Kwang Koo Kim, and Steven C. Deller. 2004. “Natural Amenities, Tourism, and Income Distribution.” Annals of Tourism Research 31:1031–50.

Mason, Charles F., Lucija A. Muehlenbachs, and Sheila M. Olmstead. 2015. The Economics of Shale Gas Development. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

McGranahan, David A. 1999. “Natural Amenities Drive Rural Population Change.” Agricultural Economic Report No. 781. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Rural Economics Division, Economic Research Service.

Mitnik, Pablo A., and Matthew Zeidenberg. 2007. From Bad to Good Jobs? An Analysis of the Prospects for Career Ladders in the Service Industries. Madison, WI: Center on Wisconsin Strategy.

Moss, Philip, and Chris Tilly. 2003. Stories Employers Tell: Race, Skill, and Hiring in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Moynihan, Daniel P. 1969. Maximum Feasible Misunderstanding: Community Action in the War on Poverty. New York: Free Press.

Murray, Charles. 1984. Losing Ground: American Social Policy 1950–1980. New York: Basic Books.

O’Connor, Alice. 1999. “Swimming Against the Tide: A Brief History of Federal Policy in Poor Communities.” In Urban Problems and Community Development, ed. Ronald Ferguson and William Dickens, 77–138. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Partridge, Mark, and Dan Rickman. 2005. “High Poverty Nonmetropolitan Counties in America: Can Economic Development Help?” International Regional Science Review 28:415–40.

Partridge, Mark, Dan Rickman, and Hui Li. 2009. “Who Wins from Local Economic Development? A Supply Decomposition of U.S. County Employment Growth.” Economic Development Quarterly 23:13–27.

Peterson, Paul E. 1981. City Limits. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Piven, Francis Fox, and Richard A. Cloward. 1971. Regulating the Poor: The Functions of Public Welfare. New York: Vintage.

Power, Thomas M. 1988. The Economic Pursuit of Quality. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Ramsay, Meredith. 1996. Community, Culture, and Economic Development: The Social Roots of Local Action. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Reeder, Richard J., and Dennis M. Brown. 2005. “Recreation, Tourism and Rural Well-Being.” Economic Research Service Report No. 7. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Roback, J. 1988. “Wages, Rents, and the Quality of Life.” Journal of Political Economy 90:1257–77.

Scheyvens, Regina. 2011. Tourism and Poverty. New York: Routledge.

Sharkey, Patrick. 2013. Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sherraden, Michael. 1991. Assets and the Poor: A New American Welfare Policy. New York, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Squires, Gregory D., and Sally O’Connor. 2001. Color and Money. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Stoecker, Randy. 1997. “The CDC Model of Urban Redevelopment: A Critique and an Alternative.” Journal of Urban Affairs 19:1–22.

Summers, Gene F., Sharon D. Evans, Frank Clemente, E. M. Beck, and Jon Minkoff. 1976. Industrial Invasion of Nonmetropolitan America: A Quarter Century of Experience. New York: Praeger.

Taub, Richard P. 1988. Community Capitalism. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Tigges, Leann M., and Gary P. Green. 1994. “Small Business Success Among Men- and Women-Owned Firms in Rural Areas.” Rural Sociology 59:289–310.

Young, Justin R. 2012. Underemployment in Urban and Rural America, 2005–2012. Durham, NH: Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire.