9

The First Model of the World

HAVE YOU EVER tried to navigate through your home in the dark? I’m guessing not on purpose, but perhaps during a power outage or a midnight stroll to the bathroom. If you have ever tried this, you probably had the (not very surprising) realization that it is hard to do. As you step out of your bedroom and walk toward the end of the hall, you are prone to mis-predicting the length of the hallway or the exact location of the bathroom door. You might stub a toe.

But you would also notice that, despite your blindness, you have a reasonable hunch about where the end of the hallway is, some intuition about where you are in the labyrinth of your home. You might be off by a step or two, but your intuition nonetheless proves an effective guide. What is remarkable about this is not that it is hard, but that it is achievable at all.

The reason you can do this is that your brain has built a spatial map of your home. Your brain has an internal model of your home, and thus, as you move, your brain can update your position in this map on its own. This trick, the ability to construct an internal model of the external world, was inherited from the brains of first vertebrates.

The Maps of Fish

This same find-your-way-to-the-bathroom-in-the-dark test can be done in fish. Well, not the bathroom part, but the general test of remembering a location without a visual guide. Put a fish in an empty tank with a grid of twenty-five identical containers throughout the tank. Hide food in one of the containers. The fish will explore the tank, randomly inspecting each container until it stumbles on the food. Now take the fish out of the tank, put food back in the same container, and put the fish back into the tank. Do this a few times, and the fish will learn to quickly dart directly to the container with the food.

Fish are not learning some fixed rule of Always turn left when I see this object—they navigate to the correct location no matter where in the tank they are initially placed. And they are not learning some fixed rule of Swim toward this image or smell of food; fish will go back to the correct container even if you don’t put any food back in the container. In other words, even if every container is exactly identical because none of them have any food at all, fish still correctly identify which container is currently placed at the exact location that previously contained food.

The only clue as to which container previously held the food was the walls of the tank itself, which had markings to designate specific sides. Thus, fish somehow identified the correct container based solely on the container’s location relative to the landmarks on the side of the tank. The only way fish could have accomplished this is by building a spatial map—an internal model of the world—in their minds.

The ability to learn a spatial map is seen across vertebrates. Fish, reptiles, mice, monkeys, and humans all do this. And yet simple bilaterians like nematodes are incapable of learning such a spatial map—they cannot remember the location of one thing relative to another thing.

Even many advanced invertebrates such as bees and ants are unable to solve spatial tasks. Consider the following ant study. Ants form a path from a nest to food and another path from the food source to their nest. They return to the nest with scavenged food, then leave again empty-handed to acquire more food. Suppose you took one of the ants on its way back to the nest and placed it on the path that is leaving the nest. This ant clearly wants to go back to the nest, but is now placed in a location from which it has only ever navigated away from the nest. If the ant had an internal model of space, it would realize that the fastest way home is to just turn around and go in the opposite direction. That is what a fish would do. But if instead the ant learned only a series of movements (turn right at cue X, turn left at cue Y), then it would just dutifully begin the loop all over again. Indeed, ants go through the entire loop again. Ants navigate by following a set of rules of when to turn where, not by constructing a map of space.

Your Inner Compass

Here’s another test you can do on yourself: Sit in one of those swivel chairs, close your eyes, ask someone to turn the chair, and then guess what direction of the room you are facing before opening your eyes. You will be amazingly accurate. How did your brain do this?

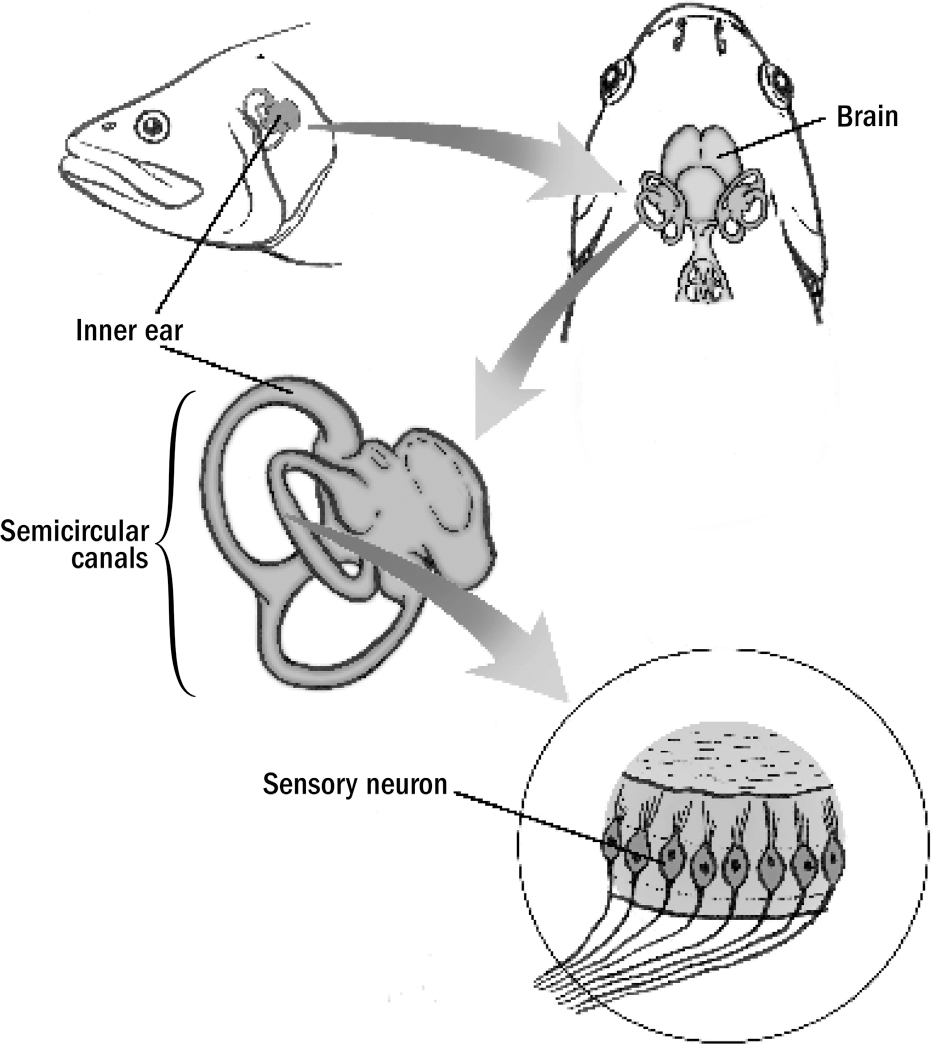

Deep in your inner ear are semicircular canals, small tubes filled with fluid. These canals are lined with sensory neurons that float in this fluid and activate whenever they detect movement. The semicircular canals are organized in three loops, one for facing forward, one for facing sideways, and one for facing upward. The fluid in each of these canals moves only when you move in that specific dimension. Thus, the ensemble of activated sensory cells signal the direction of head movement. This creates a unique sense—the vestibular sense. This is why you get dizzy if you are spun in a chair continuously—eventually, this overactivates these sensory cells and when you stop turning, they are still active, incorrectly signaling rotation even when you aren’t rotating.

Figure 9.1: The vestibular sense of fish emerges from the uniquely vertebrate semicircular canals

Image by Carlyn Iverson / Science Source. Used with permission.

The evolutionary origin of semicircular canals was in early vertebrates, emerging at the same time as reinforcement learning and the ability to construct spatial maps. Modern fish have the same structure in their inner ears, and it enables them to identify when and by how much they are moving.

The vestibular sense is a necessary feature of building a spatial map. An animal needs to be able to tell the difference between something swimming toward it and it swimming toward something. In each case, the visual cues are the same (both show an object coming closer), but each means very different things in terms of movement through space. The vestibular system helps the fish tell the difference: If it starts swimming toward an object, the vestibular system will detect this acceleration. In contrast, if an object starts moving toward it, no such activation will occur.

In the hindbrain of vertebrates, in species as diverse as fish and rats, are what are called “head-direction neurons” that fire only when an animal is facing a certain direction. These cells integrate visual and vestibular input to create a neural compass. The vertebrate brain evolved, from its very beginnings, to model and navigate three dimensional space.

But if the hindbrain of fish constructs a compass of an animal’s own direction, where is the model of external space constructed? Where does the vertebrate brain store information about the locations of things relative to other things?

The Medial Cortex (aka the Hippocampus)

The cortex of early vertebrates had three subareas: lateral cortex, ventral cortex, and medial cortex. The lateral cortex is the area where early vertebrates recognized smells and that would later evolve into the olfactory cortex in early mammals. The ventral cortex is the area where early vertebrates learned patterns of sights and sounds and that would later evolve into the amygdala in early mammals. But folded into the middle of the brain was the third area, the medial cortex.

Figure 9.2: The cortex of early vertebrates

Original art by Mesa Schumacher

The medial cortex is the part of cortex that later became the hippocampus in mammals. If you record neurons in the hippocampus of fish as they navigate around, you will find some neurons that activate only when the fish are at a specific location in space, others only when the fish are at a border of a tank, and others only when the fish are facing specific directions. Visual, vestibular, and head-direction signals propagate to the medial cortex, where they are all mixed together and converted into a spatial map.

Indeed, if you damage the hippocampus of a fish, it can learn to swim toward or away from cues, but it loses the ability to remember locations. These fish fail to use distant landmarks to figure out the right direction to turn in a maze; fail to navigate to specific locations in an open space to get food; and fail to figure out how to escape a simple room when given different starting locations.

The function and structure of the hippocampus has been conserved across many lineages of vertebrates. In humans and rats, the hippocampus contains place cells, which are neurons that activate only when an animal is in a specific location in an open maze. Damage to the hippocampus in lizards, rats, and humans similarly impairs spatial navigation.

Clearly the three-layered cortex of early vertebrates performed computations far beyond simple auto-association. Not only is it also seemingly capable of recognizing objects despite large changes in rotation and scale (solving the invariance problem), but it is also seemingly capable of constructing an internal model of space. To speculate: Perhaps the ability of the cortex to recognize objects despite changes in rotation and its ability to model space are related. Perhaps the cortex is tuned to model 3D things—whether those things are objects or spatial maps.

The evolution of spatial maps in the minds of early vertebrates marked numerous firsts. It was the first time in the billion-year history of life that an organism could recognize where it was. It is not hard to envision the advantage this would have offered. While most invertebrates steered around and executed reflexive motor responses, early vertebrates could remember the places where arthropods tended to hide, how to get back to safety, and the locations of nooks and crannies filled with food.

It was also the first time a brain differentiated the self from the world. To track one’s location in a map of space, an animal needs to be able to tell the difference between “something swimming toward me” and “me swimming toward something.”

And most important, it was the first time that a brain constructed an internal model—a representation of the external world. The initial use of this model was, in all likelihood, pedestrian: it enabled brains to recognize arbitrary locations in space and to compute the correct direction to a given target location from any starting location. But the construction of this internal model laid the foundation for the next breakthrough in brain evolution. What began as a trick for remembering locations would go on to become much more.