CHAPTER 13

Practising to improve

One way of looking at this might be that for 42 years I have been making small regular deposits in this bank of experience: education and training. And on January 15 the balance was sufficient so I could make a very large withdrawal.

It’s called practice because it doesn’t have to be perfect. Most geniuses spend a lot of time practising their skills before they start approximating great performance. Michelangelo became Michelangelo by working incredibly hard.

Practice predicts success. Almost anyone can improve their performance by practising. Geniuses seem to practise and hone their skills and abilities with a passion.

Parents who enforce practice on their children only end up with resentful people who may turn out to be successful but experience considerable periods of unhappiness. Tennis player Andre Agassi was press ganged into a training regime that made him successful but also vulnerable to drug abuse and burnout. It was only when Andre was able to discover his own passion for the game that he became truly great.

Let’s contrast Agassi with one of the greatest cricket players of all time, Donald Bradman. Bradman, seemingly without much guidance from his family, preoccupied himself for hours on end with bouncing a ball against a water tank and hitting it with a stick, a task more difficult than hitting a cricket ball with a bat.

The greatest boxer of the modern era, Muhammad Ali, returned from suspension even greater than he had been previously. Combined with his passion to be recognised for his beliefs, he also followed a punishing training regime for six days a week, with only Sundays off.

Artists, musicians and writers all develop practice routines that resemble concrete rituals. JK Rowling wrote her first Harry Potter novel in a café. The philosopher Jean Paul Sartre worked for three hours in the morning and three in the evening. Joan Miro created art from 7 am until noon then went boxing and resumed painting from 3 to 8 pm every day. Henry Miller wrote most of his works in the morning. After having a cup of coffee containing precisely 60 beans, Ludwig van Beethoven composed music from dawn until 3 pm. Today, author Haruki Murakami wakes at 4 am and writes for five or six hours when working on a novel.

These rituals can teeter towards the bizarre. Schiller filled his desk with rotten apples, Proust worked in a cork-lined room and Dr Samuel Johnson surrounded himself with a purring cat, orange peel and tea.

As discussed throughout this book, geniuses develop systems that enable them to practically develop their passions without having to make decisions.

Of course, it is highly unlikely that your child will come up to you one day and ask for a desk filled with rotten apples and a purring cat because it is now time to practise. Nevertheless it is a good idea to consider the types of practice that maximise skills to help your child learn.

This is not about drilling kids into a rigid routine of skill development. It’s about helping kids to have fun and gain a sense of success as they acquire mastery in areas they are passionate about.

Use your mirror neurons

In the rear part of our prefrontal cortex are situated some very special brain cells called mirror neurons. These mirror neurons activate when we watch other people doing intentional activities and they help us to understand how we learn from imitation and role modelling.

We learn by watching successful people in action. Some of our most important learning happens when we are doing nothing except watching.

For you, this means finding a way of showing your children the very best performers in areas in which they show interest. You learn just by watching masters at work. Whether it is watching Michael Jordan play basketball, Jane Goodall interacting with mountain gorillas, Stephen Hawking talking about physics, or the world’s most avid stamp collector discussing her collection, expose your children to the very best the world has to offer.

When you watch someone who is extremely accomplished at something with your child, there are two main ways to do it. The first one is destructive. In this way you marvel at the person’s natural gifts and talents, and convey a sense that they have abilities beyond those of mere mortals. This conveys a sense that their level of skill is beyond the abilities of your child. The other way is constructive. This means marvelling at the performance and then pointing out the dedication and hours of practice that person must have put in to be able to do it.

Deliberate practice

It’s not just any old practice routine that brings forth genius.

Deliberate practice is where you identify the areas you need to improve on and target them as areas to practise. Most of us fall into the easy trap of practising the things we are already good at. It feels good. We gain a sense of accomplishment. But if we really want to improve at something we need to find the areas where we are not so competent and focus on developing those areas.

To return to our Albert and Rex analogy for our brain, our Rex wants the easy life and is incredibly distractible. That’s why people procrastinate to avoid doing something they perceive as difficult or challenging. It always seems easier to put it off until later. The problem is the right time never arrives.

For you, this means helping your children focus on their strengths and to also identify a few areas they would like to improve in. As the pressure to perform well inhibits some children from trying new things, you may want to label this as experimental practice where they try hard things out without feeling they have to succeed every time.

Try to encourage your children to convert their practice sessions into a challenge to see how much they can improve.

The smaller the target the easier it is to hit

Often, when children set too large a goal for themselves they freeze and give up. Their awareness shifts from what they can do right now to the long-term goal.

When we focus on the outcome too much we get the yips or choke. Our focus moves away from what we can do to what is to be done. In essence we become less present in whatever we are doing. We also become more critical and less observant of what we are doing in the moment.

To avoid this, ask your children to look for small improvements they want to make. Aiming small is likely to result in greater long-term improvements than making a single push towards success.

Repetition

Doing a little bit a lot always beats doing a lot a little bit. Remember, it takes humans 24 repetitions to get to 80 per cent of competence. Repetition also builds mastery and the development of brain connections called synaptogenesis.

One major implication of this is that we improve fastest when we practise something for short periods almost every day, rather than do a practice session once or twice a week.

Spaced repetition pays off even more

Spaced repetition also has a positive impact on learning. Instead of concentrating the study of information in single blocks, learners encounter the same material in briefer sessions spread over a longer period of time.

Spaced repetition produces impressive results. A study completed at the University of California in San Diego in 2007 found that Year 8 history students who relied on a spaced approach to learning had nearly double the retention rate of students who studied the same material in consolidated units.

This research implies that the more times students encounter information the more likely they are to understand and retain it.

Mixing it up and interleaving

Mixing up tasks also pays off. Mixing it up, or interleaving, is when children practise different types of skills and it powerfully increases results. For example, you might ask children to do a short set of subtraction problems, some reading, some writing and then some addition problems.

A study published in the Journal of applied cognitive psychology asked 10-year-olds to work on solving four different types of mathematical problems and then take a test evaluating how well they had learned. The scores of those whose practice problems were mixed up were more than double the scores of those students who had practised one kind of problem at a time.

Learning occurs in a context. Spaced repetition of the same problem in a variety of contexts increases outcomes. Spaced repetition of a specific skill in a series of different contexts also pays off. For example, shooting goals from different angles.

Covering the same concept five times within different contexts is better than covering five different concepts.

Brain leaps

Research also suggests that it is when we shift from one area of learning to a dissimilar area that we learn fastest.

For example, if you have a chemistry lesson and then followed this with a physics lesson the skills gained in both lessons would conflict and you would improve more slowly. If instead you mix up the areas of learning more and shift from English to Mathematics to Art and then to Science the skills learned in each would remain distinct and outcomes improve. This also applies to any study schedules your child might develop.

Self-explanations

Practice also helps us to get the sequences of what we need to do into our heads.

Children who are able to explain to themselves the steps involved in solving academic problems achieve better academic results. They learn to mentally go through the steps of solving a problem.

For example, articulating the steps of ‘First I’ve got to do ... then I need to ... and then I can ...’ utilises one of the most powerful brain abilities – patterning knowledge. This also applies to learning a new sports skill.

Ask your children to outline the process of solving problems. Remember, explaining a process to others builds reasoning skills and clarifies thinking. Additionally, explaining or reasoning out the process of any problem makes you more present in the moment, and thus more open to improvement.

Resilience-based coaching for parents

Coercion doesn’t work, encouragement does. It is not useful for parents to be continually pointing out errors to children. Nor is it useful to have parents gushing over every attempt a child makes.

Instead you can help your children to practise in the areas they want to improve by being a catalyst for analysis. There are several steps in this conversation.

- Break down a task into segments. It could be different parts of an assignment that is due in a few weeks at school, it could be a musical piece, or a foreign language they are learning.

- Ask your child to rate their level of confidence in each segment or component. You might ask them to rate themselves out of ten with zero equalling totally incompetent and ten equalling mastery. Children will vary in terms of the accuracy of their rating, but just accept it.

- Then ask them how many points further up the scale they would like to work on next. Aim for about a two-point jump. So if a child assessed his or her skill at spelling at five out of ten, you might discuss what seven out of ten would look like. Ask them to describe what they see as the difference between their current rating and a few points up the scale.

For example, ‘So you say you are a five out of ten speller at the moment, but you’d like to be a seven out of ten speller.’ Tell me what you think you would be able to do if you were a seven out of ten speller?’

If children rate themselves at two out of ten but want to be ten out of ten, advise them to slow down and break their improvement practice into smaller bits. For example, ‘Okay you want to be ten out of ten. Why don’t we aim to get to four out of ten in the next few weeks?’

If children rate themselves at ten out of ten, say, ‘Okay, let’s talk about what a twelve out of ten might look like.’

- Once children have outlined the differences between their current performance and two points further up the scale, ask them to notice when that happens. If a child says, ‘Well, if I was two points up the scale I would be able to spell big words like hippopotamus and Mississippi.’ You can then say, ‘So just notice when you spell those words correctly and let me know.’

As Timothy Gallwey discovered, directing people’s awareness is much more powerful than giving pep talks or even giving direct instructions about how to improve. (See more about his coaching methods in Chapter 8.)

- You might like to leave the matter there and resolve to positively comment on your child’s efforts to improve, or you could ask your child, ‘Would you like to work out a system for practising the hard bits as well as the easy bits?’ For example, if they are learning a musical piece they might break the entire performance into a series of segments, rate each one and then spend more time practising the harder parts.

If your children are struggling in mathematics, you might ask them to rate their level of confidence in addition, subtraction, division and multiplication and then plan to spend more time on the ones that they are less competent in.

How practice applies to school success

Almost everyone gets stressed when there are major exams and assessments. Even successful students who perform well on practice questions can find their performance drops in test conditions.

One of the biggest barriers your children face at school is not their level of intelligence. They have enough intellectual power. The biggest barrier is anxiety. The best way to reduce anxiety is to have a practice routine.

Students who spend ten minutes writing about their worries before mathematics tests at school perform roughly 15 per cent better than those who just sit and do nothing before an exam.

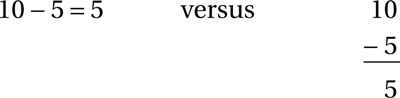

Remember that anxiety raises levels of cortisol, which shuts down memory and language processing. Mathematics problems presented horizontally seems to be more reliant on verbal brain processing than the same problems presented vertically.

If an anxious child is having difficulty understanding the first example (10 − 5 = 5), which is processed by the brain like a sentence and is therefore more affected by anxiety, teach him or her to lay out the problem vertically. Vertically presented problems use more spatial reasoning which is less affected by a spike in cortisal.

The way children interpret feelings of anxiety also influences their performance. Feelings of stress and anxiety often help us get ready for a challenge. If children can interpret their body’s response as a call to action rather than an onset of stupidity they will do better.

How you can help anxious children to practise something new

- Reaffirm their self-worth – remind them about their abilities. They know more than they think they do.

- Help them to farewell the fears. Firstly help them to acknowledge what they are worrying about. Explain it and name it. Say something like, ‘I’m worrying about this test because I feel it will be hard.’

- Thank the worries for trying to help them get ready to do better.

- Tell children to let go of the worries – don’t attach any more brain power to them.

- Move from stress to energy – suggest children use the worry to get some practice done.

- Doodle – if children get stuck, suggest they muck about with things. Their brain is smarter than they know.

- Have children practise under pressure – test using practice questions.

- Outsource their memory – make audio recordings, posters, flash cards or summary hands (see Chapter 11), or use memory methods such as the BASE or journey method (see Chapter 12). Find some way of keeping them organising what they know (see Chapter 11).

| Approaching practice in positive ways | |

|---|---|

| Ages 2–4 |

|

| Ages 5–7 |

|

| Ages 8–11 |

|

| Ages 12–18 |

|