Nazirites (6:1–21)

Vow (6:2). Vows among ancient Near Eastern cultures from Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Levant reflect the following pattern: (1) The vow grows out of a situation of need or distress; (2) it is made by a human to the gods; (3) it is generally conditional in nature; (4) a responsive votive offering is offered publicly at a cultic place at the conclusion of the vow conditions.49

Abstain from wine and other fermented drink (6:3). Restrictions for the Nazirite are more stringent than those for the priest here, because the priest need only refrain from fermented beverage during his period of service in the sanctuary (Lev. 10:9). A Nazirite must abstain from all vineyard products at all times, defined in detail down to the grape hulls, pits, and even the vines.

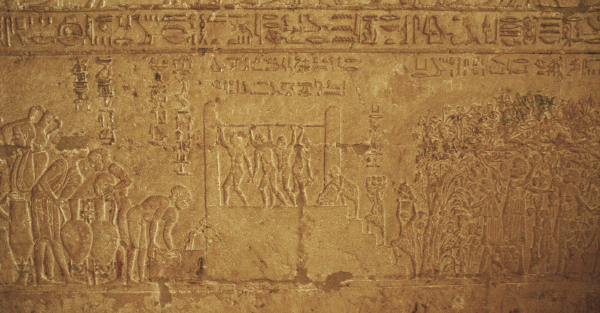

Relief from the tomb of Petosiris, High Priest of the god Thoth, shows the grape harvest, and people pressing grapes.

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

The intoxicant beverages are listed as “wine” (yayin) and “other fermented drink” (šēkār). Wine was the most common form of grape beverage, produced in the late summer and early fall in ancient Israel in winepress installations and then stored in subterranean bell-shaped caves for fermentation. Numerous examples of these installations from the Bronze and Iron Ages have been excavated in Israel, such as those at Gibeon, Beth Shemesh, Samaria, and el-Burj.50

The “other fermented drink” has historically been translated as “beer,” a common Mesopotamian and Egyptian beverage known from inscriptions and carved or painted murals, or as “strong drink.” L. E. Stager suggests that šēkār may refer to a grape distillate such as grappa or brandy, a term that gave rise to the verb šākar (“to be drunk”). Such a product had an alcohol content of 20 to 60 percent by comparison to wine’s 12 to 14 percent.51 The emphasis here is total abstinence from anything associated with the vineyard, lending support to the interpretation of šēkār as an intoxicating beverage produced from vineyard produce.52

Model of Egyptian beer makers

Anthony M. Warnack, courtesy of the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum

No razor may be used on his head (6:5). The visible distinctiveness of allowing the hair to grow long and remain uncut for the duration of the vow set the Nazirite apart from societal norms. In Mesopotamian and Mediterranean law codes, hair played a significant role in ritual and legal practices. In Hammurabi’s law code, cutting one’s hair was a form of punishment and humiliation for bringing a false accusation against another man’s wife in matters of property.53 In a ninth-century B.C. Cypriot bowl inscription, a person’s hair was presented to Astarte as a memorial offering.54 In a Hellenistic era temple repair and rededication ritual, the king’s hair was cut and presented as an offering to the local deity in a special votive vessel.55

In contrast to Canaanite priestly practices, levitical regulations prohibited Israelite priests from allowing their heads to be shaved bald or trimming the edges of the beard, as well as cutting themselves (Lev. 19:26–28; 21:5–7). Olyan notes that shaving rites mark a ritual transition, altering the status of the one shaved. By shaving the head one entered into the realm of social control, whereas long hair symbolized separation from social control.56 From Emar, a ritual for the installation of the high priestess (NIN.DINGIR) of the storm god involved a “Shaving Day,” which was concluded by anointing the head with oil.57

He must not go near a dead body (6:6). Touching or even coming into close proximity with a corpse was a common means of ritual contamination. To maintain the sanctity of a vow, a Nazirite could not participate in the standard ritual mourning for the dead, even a member of one’s own family. Verses 9–12 provide for accidental contamination, whereby the Nazirite removes the outward symbol of identification by shaving the hair and offering it to Yahweh at the conclusion of the period of uncleanness. Restriction also included the levitically prohibited participation in ritual associated with the cult of the dead. This practice stood in contrast to pagan ritual related to the cult of the dead58 (see comment on 3:12–13).

Drinking wine to the point of drunkenness was also part of the pagan cult of the dead ritual, as described in the Ilu’s Marzihu account from Ugarit (cf. Heb. marzēaḥ, “funeral meal”).59 The story of Samson implies that the restriction also applied to animal corpses since he withheld from his parents the knowledge that the honey he presented them was gathered from the carcass of a lion he had killed with his bare hands (Judg. 14:5–9).

Boiled shoulder of the ram (6:19). Normally the breast and the upper portion of the right hind leg were reserved for priestly consumption (Lev. 7:30–35). A similar practice seems apparent in Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Hittite texts and murals in which the right thigh was the choice portion for presentation to various deities.60 The boiling of sacrifices is known from pre-Israelite Lachish61 and premonarchical Shiloh (1 Sam. 2:13–14).

Thigh offering

Rama/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

Wave offering (6:20). To wave or elevate an offering before Yahweh is a ritual act signifying the transfer of the offering from the property of the offerer to Yahweh (see comment on 18:11).