The origin of music and musical instruments is lost in the mists of time. Since this is neither the time nor the place to explore the evolution of musical instruments, for our purposes we need only state that in the third millennium before Christ there was already, in both Sumer and Egypt, evidence of stringed instruments such as zithers, lyres, lutes, and harps. In the Iliad, Homer mentions the lyre and the zither, basic Greek instruments that were adaptations of more ancient instruments.

From Greece and Rome, musical instruments followed two main routes. The first led to the Middle East via the Arabs, who cultivated music with great refinement and brought to Spain instruments like the lute (from ud in Arabic), the Moorish guitar, and the rebec (or rabel), a small stringed instrument played with a bow, a direct ancestor of our violin. The second route was from Byzantium to the north, by way of Italy. Later on, these instruments of common origin would meet again, after having evolved differently. For example, the Latin guitar, the Moorish guitar, and the Moorish lute are plucked with a bird feather, whereas the European lute, the rebec, and its European equivalent, the giga (or geige), are strummed with the fingers. In fact, the duality of giga and rebec still exists to this day. A violin is still called a Geige in German, and a certain type of violin is a rebeca in Portuguese. However, one must not confuse the rebec or the geige with the violin. As Adolfo Salazar points out, “The semantic evolution loses its connection with the instrument: the ancient rabel . . . although it might have been the violin’s ancestor, today has become a different instrument.”1 The same could also be said of the giga or the geige.

In ancient times, the words kytara in Greek and fidicula in Latin applied to the same common ancestor of the Greek lyres and zithers. The kytara engendered a series of instruments such as the guitar. The Latin term fidicula is a philological goldmine. In the Romance languages, fidicula dropped the d and evolved into the medieval French fielle or vielle and subsequently into viole; in Italian it became viola; and in Spanish, viela, viola, and vihuela. In the Germanic languages, fidicula evolved into the Anglo-Saxon fidele and eventually to fiddle in English; in High German it became fiedel and videl. In Spain, vihuela was a generic term applied to stringed instruments with a flat back and neck and with strings that were plucked with the fingers, a plectrum, or a feather, or else played with a bow.

The introduction of the bow was a turning point in the evolution of stringed instruments from ancient times to the Renaissance. The sound produced by plucking the string is brief and tends to fade. On the other hand, the bow allows for continuous sounds of variable duration and intensity. The bow, unknown to the cultures of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Crete, and Greece, came from the Orient. The earliest evidence of its existence is found during the ninth century in Central Asia, which was probably where the distant ancestor of the European and Chinese bows originated. I will return to this subject in another chapter.

The cello’s first appearance in the music world was in sixteenth-century Italy, a few years after its siblings, the violin and the viola, had arrived. The earliest record of its existence is a fresco painted in 1535–1536 by Gaudenzio Ferrari in the Church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli in Saronno, near Milan. The fresco, which also includes the violin and the viola, depicts an angel playing a primitive version of the cello.2

It is common knowledge that the violin, the viola, and the cello belong to the violin family, which arose just as another family of stringed instruments, the violas da gamba, or viols, reached its height of popularity.

From its Italian name, the viola da gamba may be thought to have originated in Italy. However, according to some fifteenth-century paintings, it seems that the oldest of these instruments actually came from Spain—from Valencia, to be more precise. A Renaissance viol is depicted in a Virgin and Child, dated around 1475, in the chapel of St. Félix, in Játiva, Valencia.3 From Valencia, the viola da gamba, or vihuela de arco—as it was also known in Spain—spread throughout the Mediterranean to the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, and Italy. Although none of these primitive violas da gamba has survived, in 1658 Vincenzo Galilei, Galileo’s father, confirmed their Spanish origin: “In Spain one finds the first music ever written for violas, but the most ancient instruments are now found in Bologna, Brescia, Padua and Florence.”4

Obviously, Renaissance instruments were not born with a perfectly defined shape or with specific names. Furthermore, the initial problems of terminology have led to considerable confusion. The names violin and cello—violino and violoncello in Italian—appeared much later than the instruments themselves. By the 1500s, the Italian term viola was applied not only to our present-day viola, but also to all stringed instruments played with a bow. In turn, these instruments were divided into two great families: the leg viols, or violas da gamba (so named because they were held between the musician’s legs), and the violas da braccio (held in the arm).

Both the violas da gamba and the violas da braccio came in different sizes. The individual instruments from each family were named according to their relative musical registers. The most common violas da gamba were the viola da gamba soprano, the viola da gamba tenor, and the viola da gamba basso.5 The members of the violas da braccio family were also distinguished by their different tessituras. The violin was known as a soprano di viola da braccio (or violone da braccio), and our present-day viola was an alto di viola da braccio; the cello was a basso di viola da braccio, and our double bass was called a contra basso di viola da braccio, although these last two were not held in the arm.

It is important to clarify a common misunderstanding: the instruments of the gamba family did not give rise to the violin family. While they both had similar ancient origins, they existed simultaneously.6

The term violone da braccio was applied to the violin at the beginning of the sixteenth century, whereas the definitive, diminutive term violino appeared in Italy in 1538. By the seventeenth century in Italy, the basso di viola da braccio—our cello—was simply called violone. The diminutive terms violoncino and violoncello appeared in 1641 and 1665, respectively, more than a century after Ferrari’s 1535 fresco.7 By the end of the seventeenth century, the term violoncello was already in common use.

No term has had a more curious evolution than alto di viola da braccio—our viola. In seventeenth-century Italy it was called simply viola da braccio, and soon after, the term da braccio disappeared and only the word viola remained; in German, alto and viola disappeared and only braccio remained, giving rise to Bratsche. In France, alto di viola da braccio dropped viola and braccio, so this instrument is known in French simply as alto.

The violas da gamba reached their distinctive shape during the fifteenth century, well before the violas da braccio. They were characterized by flat backs, broad necks, gut frets, six or seven thin strings, and a beautiful, though somewhat pale and flat, sound.

In Spain, one of the most remarkable musicians of the sixteenth century was Diego Ortiz, from Toledo. He was a famous viola player, and his Tratado de glosas (Rome, 1553) is one of the first masterpieces in the art of variation and fantasy.

In England, the violas da gamba, called viols, were used in small instrumental groups called consorts, a word that has the same origin as concert. A viol consort generally included six viols of different sizes. They were also used in the consort songs, which were written for voice and viols and whose most famous composer was William Byrd.

In seventeenth-century Germany, the viola da gamba, still regularly used by J. S. Bach, was on the verge of extinction when the German school of gambists closed down. It disappeared in 1787 after the death of Carl Friedrich Abel, the instrument’s last great virtuoso.8

In France the popularity of the gambas, called violes in French, lasted longer. From 1675 to 1770 the French school of the gamba was the most important in Europe, and its most celebrated exponent was Marin Marais (1656–1728), author of the well-known Pièces de violes.9

In less than two centuries, the violin family displaced the viola da gamba group and occupied a predominant place in music. Why such a radical transformation? Although this is a fascinating topic, this brief overview is not the occasion for an in-depth analysis. I need add only that art is always a reflection of historical evolution and that, therefore, both music and musical instruments undergo the transformations imposed on them by particular eras.

The Baroque period, which began in 1600, marked the beginning of a musical revolution. The lyrical madrigal of the sixteenth century gave way to musical drama. New generations searched for a deeper emotional content and a more expressive musical style. Logically, the new style was launched with the most flexible of all instruments: the human voice. Italian singers sometimes expressed their emotions with such passion that, for example, at a performance of a Monteverdi opera at the court of Mantua in 1608, many of the spectators barely held back their tears during a scene in which Arianna, abandoned by Theseus, breaks into a heartrending lament.

It is natural that violin makers and violinists would attempt to create an expressive quality in their instruments, one that came as close to the human voice as possible. The newborn violin had three fundamental advantages over the viola da gamba soprano or the pardessus de viole: a more powerful sound, greater expressive capacity, and the possibility for a greater display of virtuosity. We find the same advantages in the cello and the viola in relation to the bass and alto violas da gamba, respectively.

However, this substitution did not take place without fierce opposition. The musical elite and the aristocracy were especially partial to the violas da gamba. The French composer Philibert Jambe de Fer (1515–1556), in his Epitome musical (1556), described the differences between both families and consigns the violin to the lowest musical level, regarding it as “suitable only for dances and processions”. Claude-François Ménestrier, author of the book Des ballets anciens et modernes (1682), described the violin as extremely noisy (“quelque peu tapageur”).10 In 1705 Jean Laurent Lecerf de la Viéville, in his Comparaison de la musique italienne et de la musique française, wrote that “the violin is not a noble instrument; the whole world agrees.”11

The attacks against the cello were similar but lasted much longer. In 1740, Hubert Le Blanc wrote a Défense de la basse de viole contre les entreprises du violon et les prétentions du violoncel, where he bemoans the fact that the cello, “a wretched, despised poor devil, who instead of starving to death as could well be expected, now even boasts of replacing the bass viola da gamba.”12 He adds that since the screeching sounds of the violin and the cello cannot possibly rival the delicacy and elegance of the violas, they must resort to huge halls, totally unsuitable to the violas da gamba. This comment actually reveals the disadvantage of the violas da gamba: their weak sound made them almost inaudible in the great concert halls. Ironically, and everything being relative, those “huge halls” were, in fact, the court salons, whose small size is now considered ideal for chamber music.

The anatomy of stringed instruments is described in almost human terms. We refer to the instrument’s head, neck, body, ribs, waist, and even its “soul.” The cello, like the violin and the viola, comprises over seventy different parts. Figure 1 displays the principal pieces of this instrument.

First, let us examine the exterior.

The top (belly or soundboard) generally consists of two pieces of spruce or pinewood attached to the entire length of the central line.

The back is generally made of two matching pieces of maple and, sometimes, poplar.

A very fine triple line called purfling runs parallel to the two edges of the top and back. There are two inlaid outer strips of black-tinted wood and an inner strip of black poplar. The purpose of the purfling is not merely aesthetic, since it also prevents cracks in the edges.

The ribs (or bouts), also maple, are attached to the top and the back. There are six altogether, three on each side. The first, or upper, bout runs from the neck to the beginning of the waist; the second, or middle, bout is the waist itself (also called C because it is shaped like the letter); the third runs from the waist to the lower central part of the instrument. The interior is reinforced with narrow wooden strips called linings, which reinforce the structure of the ribs.

The head, made of maple, ends in the scroll, which is often very beautiful. The function of the head is to house the pegbox: its four pegs, usually made of ebony, hold the upper end of each string, and the tension of a string is adjusted by turning its peg.

The neck is the piece that joins the head to the body of the instrument. In the past, both the neck and the head were made of a single piece of maple. Since today longer necks are required, new ones have been inserted into the original heads of old instruments. The rest of the instrument consists of modern-day pieces that can be changed with relative ease.

Attached to the neck is the ebony fingerboard, along which the strings run lengthwise. The fingerboard provides the surface against which the fingers press the strings and determine the notes to be played.

The bridge, made of maple, transmits the vibrations of the strings to the top, or soundboard. Selecting a well-carved bridge made from the right kind of wood is indispensable for obtaining optimal sound from the instrument. The bridge, an exterior piece, is not attached to the top, but is held in place by the pressure of the strings.

The instrument’s interior serves as a sounding board or sound amplifier: sound waves are emitted through two openings, called f-holes because of their shape, on both sides of the bridge.

The tailpiece is the section attached to the lower ends of the strings. It was formerly made of ebony, and sometimes of boxwood or rosewood, though today plastic is generally used. The tailpiece is fastened to the plug by a strap that was usually a cord of catgut, but today is either a steel wire or a synthetic filament.

The four strings of the cello are, in descending order, A, D, G, and C. Originally, the strings were made of catgut. Today they tend to be steel or a synthetic material wound with steel, aluminum, tungsten, or other metal.

The end pin is a cylindrical piece, generally made of steel, with a sharp point and an adjustable length; it allows the player to conveniently set the cello on the floor.

The mute (not illustrated), is a comb-shaped rider that, when placed on the bridge, reduces the vibrations of the bridge and produces a muffled sound.13

Let us now examine two vitally important pieces in the interior of the cello. The bass bar is a long narrow piece of pine attached to the interior of the top and running underneath the foot of the bridge, next to the lowest string—hence the name bass bar. Its function is to make the top more resistant to the strong pressure exerted by the strings over the bridge.

Finally, there is a piece so sensitive and vital that it is called the “soul” in all Latin languages.14 In English, it is called the soundpost. It is a small cylindrical bar of spruce, perpendicular to the top and the back, near the foot of the bridge, and opposite the bass bar. It is not attached; rather, it is held fixed to the back by the pressure of the bridge on the top. Its purpose is to transmit the vibrations of the top to the back and then to send them resounding throughout the entire interior of the instrument. Its precise placement is fundamental to producing a good sound, and the slightest change in its position will alter the quality and volume of the sound. The ideal placement depends not only on the instrument but also on the musician.

The importance of the bow is such that even the finest instrument cannot reach its tonal potential—in both volume and quality—if it is not played with a good bow.

The earliest literary and artistic references to the existence of a primitive bow date as far back as the ninth century in Central Asia—in Transoxiana Sogdiana, Khwarizm, and Khorasan—in what today would approximately be Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. In the Arabic and Byzantine empires, the use of the bow was already common during the tenth century, as corroborated by certain Byzantine illustrations and Arabic documents.15

As in the case of stringed instruments, it was the Arabs who introduced the bow to Europe through the double route of Spain and Byzantium. A Spanish manuscript dated 920–930, a copy of a work by Beatus of Liébana, contains one of the most ancient Spanish representations of a bow. The manuscript, written in the time of Abd ar-Rahman iii, caliph of Córdoba, includes a beautiful colored illustration depicting seven angels and four musicians playing bowed instruments.16

The great modern bow-making tradition began in the eighteenth century with François Tourte (1747–1835), the most brilliant bow maker in history—the Stradivari of bow makers. He was born ten years after the death of Stradivari and, like him, lived a long life, dying at the age of eighty-eight. His life was characterized by an unflagging dedication to his art, from which he retired at the age of eighty-five when his sight began to fail. He worked all day in his small workshop in Paris, located at 10 Quai de l’École, overlooking the Seine. His only pastime was fishing on the river at sunset after a long day’s work.17

The bows that existed prior to Tourte, even those made by Arcangelo Corelli, did not succeed in extracting the instruments’ full range of rich sounds. To familiarize himself with musicians’ particular requirements, Tourte worked with the greatest virtuosos of the time, especially with the violinist Giovanni Viotti. Although Tourte did not invent the bow, he established the ideal model by standardizing the dimensions, weight, and balance, and, most particularly, by introducing or reintroducing pernambuco wood from Brazil, the only kind of wood that provides the optimum combination of flexibility, elasticity, resistance, and weight. Tourte paid meticulous attention to the horsehair for his bows, selecting each of the 200 hairs for its perfect roundness and uniform length; he was assisted by his daughter, who, it is believed, added the tiny label with the following text found in one of his bows: Cet archet a été fait par Tourte en 1824, âgé de soixante-dix-sept ans. (This bow was made by Tourte in 1824, at 77 years of age.)18 Tourte’s bows were genuine masterpieces, not only because of their incomparable beauty and perfection, but also from the tone they produce in great instruments when played by an artist.

The French school of bow making prevailed in this art, just as violin making had been dominated by the Italians. Among Tourte’s successors we should mention François Lupot (1774–1837), Nicolas Eury (1810–1835), Dominique Peccatte (1810–1874), who today is regarded almost on the same level as Tourte, François Nicolas Voirin (1833–1885), and others. There were also outstanding bow makers from other countries: John Dodd (1752–1839) and James Tubbs (1835–1919) from England, and Nicolas Kittel (1839–1870) from Russia.

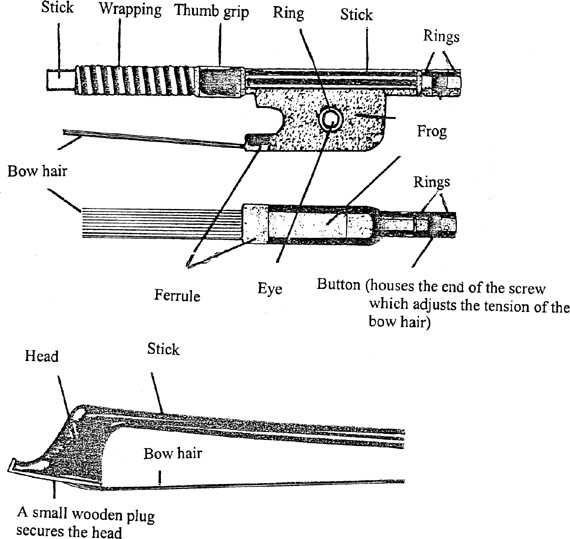

Figure 2 shows the principal parts of the bow. The thickness of the stick is not uniform: its dimensions are determined by a precise mathematical formula. The stick’s curved shape is obtained through an application of dry heat, requiring a highly developed sense of touch on the bow maker’s part.

2. The anatomy of a bow. BOTTOM: The head of the bow. TOP: The frog of the bow (side and bottom view).

3. Cello bows by (LEFT) Francois Tourte, (CENTER) Dominique Peccatte, and (RIGHT) William Salchow (a modern bow). Photos by Isaac Salchow.

It is curious that few violinists and cellists ever stop to think about the extraordinary number of materials required to make a bow. As I have already mentioned, the stick is made of a wood called pernambuco, the finest grade of brazilwood. This wood, which comes from a tree called pau-brasil in Portuguese and palo brasil in Spanish or brasilium in Latin, had been known in Europe since the eleventh century, since it also grows in other places. This was the tree that gave its name to Brazil (and not the other way around) when the Portuguese discovered great forests of these reddish trees in the territory later known as Brazil.

The frog is made of ebony (a wood from the central regions of Africa), tortoiseshell, or ivory; use of the latter two is severely restricted today to prevent the extinction of turtles and elephants. Mother-of-pearl is used for the eye of the frog and for the ring that sometimes surrounds it. Silver or gold is generally used for the ferrule. Just above the frog, where the fingers touch the bow, there is a protective wrapping; once made of whalebone, it is now leather, silver wire, or gold wire. A steel screw adjusts the tension of the hair. Finally, bow hair comes from the tails of white horses, preferably those from cold regions. Since the hairs tend to break with use, they must be replaced every two or three months; that is, the bow must be rehaired.

For years I have used an excellent bow made by François Tourte and a modern bow by William Salchow, a renowned New York bow maker whose cello bows are exceptionally good. Whenever possible, I always entrust Salchow with rehairing my bows, since the quality of the bow hair is fundamental. Salchow generally obtains hair from Russian or Mongolian horses: they are raised on the cold steppes, and their thick hair ensures optimal quality.

Figure 3 illustrates three cello bows: one by François Tourte, another by Dominique Peccatte—the model called tête de cygne (swan’s head) because of its delicately shaped point—and the last by William Salchow.

If one places new hairs in a bow and then glides them across a string, no sound will be produced, since the contact of the clean hairs with the string does not produce any vibrations. To produce sound, the hairs need to be coated with hundreds of diminutive solid particles, which, upon coming into contact with the strings, create a rapid succession of shocks and a continuous vibration, resulting in the emission of sound. This is the function of rosin, which must be frequently applied to the bow. The rosin for bows is obtained from the sap, or resin, of certain kinds of pine trees. When refined through various processes, the sap is used for medicinal, commercial, and artistic purposes. In ancient times, the resin from Colophon in Greek Ionia (in Asia Minor) was regarded as the very finest, so rosin is called colophane in French, colofonia in Italian, and kolophon in German, whereas the Spanish name is resina. Good rosin is obtained only after a careful selection of the best raw material and a manufacturing process that adheres to the strictest quality-control standards. Certain kinds of rosins are more appropriate for violins or violas, and other, slightly different, types are more suitable for cellos and double basses.