As we have seen, over the past few centuries the cello did not receive as much attention from composers as the violin and piano did. On the other hand, the twentieth century produced a veritable explosion of works for the cello. Significant improvements in the cello-playing technique and the advent of brilliant, charismatic cellists soon raised the cello to the same rank as the other main solo instruments and attracted the attention of numerous great composers. At the same time, many composers and cellists from countries not traditionally associated with the musical world appeared on the scene.

Never before have there been so many brilliant cellists—and from so many different countries—as there are today. Since any list I could possibly submit here would probably be woefully incomplete, I will briefly discuss only a few cellists who deserve special mention because of their impact on music and their relevance to this book.1

Naturally, the first cellist to be discussed here is Pablo Casals. His incomparable artistry and powerful personality transformed him into a public figure who, beginning in the early part of the century, succeeded in awakening unprecedented interest in the cello.

Casals was born in the small Catalan town of El Vendrell, and at the age of twelve was accepted at Barcelona’s prestigious Municipal School of Music. He met Isaac Albéniz, who, impressed with Casals’s obvious talent, gave him a letter of introduction for the Count de Morphy, secretary of Queen María Cristina, mother of and regent for the future King Alfonso xiii, who was then still a child.

Albéniz’s letter gave Casals an entrée to the royal palace, and soon, in Casals’s own words, Queen María Cristina became his “second mother.” For over two years he remained in Madrid, where he pursued his music studies and attended concerts and exhibitions under the Count de Morphy’s guidance.

The queen granted him a scholarship to continue his studies at the Brussels Conservatory. At the age of nineteen, his mother and siblings departed for Brussels, a journey involving considerable financial sacrifice. F. A. Gevaert, the director of the conservatory, introduced him to the cello teacher. The following incident, told in his own words, is highly illustrative of the character that distinguished Casals all his life.

The next day I appeared at the class. I was very nervous . . . I sat in the back of the class, listening to the students play. I must say I was not too greatly impressed, and I began to feel less nervous. When the class had finished, the professor . . . beckoned to me: “So,” he said, “I gather you’re the little Spaniard that the Director spoke to me about.” I did not like his tone. I said yes, that I was the one.

“Well, little Spaniard,” he said, “it seems you play the cello. Do you wish to play?”

I said I would be glad to.

“And what compositions do you play?”

I said I played quite a few.

He rattled off a number of works, asking me each time if I could play the one he named, and each time I said yes—because I could. Then he turned to the class and said, “Well now, isn’t remarkable! It seems that our young Spaniard plays everything. He must be really quite amazing.”

The students laughed. At first I had been upset by the professor’s manner—this was, after all, my second day in a strange country—but by now I was angry with them and his ridicule of me. I didn’t say anything.

“Perhaps,” he said, “you will honor us by playing the Souvenir de Spa?” It was a flashy piece that was trotted out regularly in the Belgian school.

I said I would play it.

“I’m sure we’ll hear something astonishing from this young man who plays everything,” he said. “But what will you use for an instrument?”

There was more laughter from the students.

I was so furious I almost left then and there. But I thought, all right, whether he wants to hear me play or not, he’ll hear me. I snatched a cello from the student nearest to me, and I began to play. The room fell silent. When I had finished, there wasn’t a sound.

The professor stared at me. His face had a strange expression “Will you please come to my office?” he said. His tone was very different than before. We walked from the room together. The students sat without moving.

The professor closed the door to his office and sat down behind his desk. “Young man,” he said, “I can tell you that you have a great talent. If you study here, and if you consent to be in my class, I can promise you that you will be awarded the First Prize of the conservatory.”

I was almost too angry to speak. I told him “You were rude to me, sir. You ridiculed me in front of your pupils. I do not want to remain here one second longer.”2

The next day, the Casals family immediately left for Paris. The young cellist wrote to the Count de Morphy, describing the incident. The count, who was extremely vexed, chastised Casals for his insubordination and presented him with an ultimatum: either return to Brussels or lose his scholarship. However, even then there was no power on earth that could make Casals change his mind once it was made up. The family remained in Paris, where they underwent considerable hardship.

On his return to Barcelona, his life began to improve. Josep García, his cello teacher at the Municipal Music School, had been appointed first cellist of the Liceu. Casals made peace with Count de Morphy and Queen María Cristina, who, after a concert at the Royal Place, presented him with a Gagliano cello.3

Another letter of recommendation from Count de Morphy introduced Casals to the famous French conductor Charles Lamoureux, who invited him on the spot. His legendary Paris debut in 1899—where he played the first movement of the Cello Concerto in D Minor by Edouard Lalo—was the first step in his glorious career as a world-famous cellist.

His life was profoundly altered by the Spanish Civil War. From the beginning of the conflict, his position was unequivocally in favor of the Republican forces. Soon after the end of the war, Casals settled in the small village of Prades in southern France. The advent of the Second World War further complicated his life, particularly after the establishment of the Vichy regime. His American friends sent him numerous invitations urging him to move to the United States, where he would be safe and also earn a fortune with his concerts. Casals refused. He felt it was his duty to remain with his fellow immigrants in exile and assist them in every possible way. “The artist is first a man and, as such, he must make common cause with his companions. The blood that has been shed and the tears from the victims of injustice are far more important to me than my music and all my cello recitals,” Casals declared.4

When the war ended, Casals decided to end his exile and play in public once again, starting with several memorable concerts in England and Paris. Believing that the days of the Franco regime were numbered, he was certain that his exile was coming to an end. But Casals was deeply disillusioned by the tolerance shown by Western governments toward a totalitarian regime that had received support from the Nazis and the Italian Fascists. In 1946 Casals announced that he would not accept any invitations from any country “until Spain reestablished a regime that was respectful of fundamental liberties and popular will. I myself closed all doors. It was the most painful sacrifice an artist could ever impose upon himself.”5

Then came 1950, the year commemorating the bicentennial of Bach’s death. In light of Casals’s refusal to abandon his self-imposed exile, a group of musicians—mostly from the United States, though headed by Russian violinist Alexander Schneider—proposed that they join Casals in Prades to celebrate the glory of Bach. Thus, in 1950 the most eminent musicians of the time helped establish the Prades Bach Festivals, which lasted—with only a few interruptions—until 1960.

Casals has been a legendary figure to me since I was eight or nine years old. His unique tone produced a profound impression on me from the very first time I ever heard him. I remember often listening to his recordings of Boccherini, Dvo ák, and Bach’s suites. Then, in 1950 I had the good fortune of meeting Casals. My father, who was a friend of his, arranged to visit him on January 1, 1950, which happened to be my thirteenth birthday. Don Pablo welcomed us most graciously in his modest house and conversed with my parents on a number of subjects, such as their many friends in common, mostly Spanish exiles in Mexico. When he learned that I was studying the cello, he asked me to play something for him. On an instrument he lent me, I played a Bach adagio that had been transcribed by Casals himself. He did not interrupt me, but as soon as I finished he said, “You have talent, young man, but I’m going to show you how this adagio should be played.” Without removing his pipe from his mouth, he proceeded to show me, occasionally pausing to explain certain details that he believed were important. That visit with Casals has remained deeply etched in my memory.

ák, and Bach’s suites. Then, in 1950 I had the good fortune of meeting Casals. My father, who was a friend of his, arranged to visit him on January 1, 1950, which happened to be my thirteenth birthday. Don Pablo welcomed us most graciously in his modest house and conversed with my parents on a number of subjects, such as their many friends in common, mostly Spanish exiles in Mexico. When he learned that I was studying the cello, he asked me to play something for him. On an instrument he lent me, I played a Bach adagio that had been transcribed by Casals himself. He did not interrupt me, but as soon as I finished he said, “You have talent, young man, but I’m going to show you how this adagio should be played.” Without removing his pipe from his mouth, he proceeded to show me, occasionally pausing to explain certain details that he believed were important. That visit with Casals has remained deeply etched in my memory.

In 1954 Casals said, “If some day there is a change in the circumstances that keep me in Prades, the first country I would like to visit is Mexico, as a tribute to their great loyalty toward democratic Spain.”6 In December 1955 and January 1956, Casals fulfilled his long-cherished dream of visiting Puerto Rico, his mother’s birthplace, and fulfilled his promise to return to Mexico. Casals’s visit to Mexico was extremely brief. For medical reasons, he traveled only to Veracruz, since Mexico City’s high altitude could have proved detrimental to his health. There were no direct flights from Havana, the first stop on his trip, to Veracruz, since all of them stopped over in Mexico City first. Therefore, my father—a prominent industrialist, an excellent musician, and a patron of the arts and humanitarian causes—arranged for a private plane to transport Don Pablo from Havana to Veracruz. My father even flew to the Cuban capital with my mother and brother to accompany him on this trip. At that time I was studying for my exams at MIT, so I decided to forgo the historic opportunity to accompany my parents and Casals on this particular trip. Needless to say, today I deeply regret my excessive academic zeal.

Three years later, Casals returned to Mexico—to the city of Xalapa, where he attended the Pablo Casals Music Festival and the Second International Cello Competition. The competition took place from January 19 to January 31, 1959. The members of the judging panel, presided over by composer Blas Galindo, included cellists Pablo Casals, Gaspar Cassadó, Maurice Eisenberg, Rubén Montiel, André Navarra, Zara Nelsova, Adolfo Odnoposoff, Mstislav Rostropovich, Milos Sadlo, and Brazilian composer and cellist Heitor Villa-Lobos.7

In 1956 Casals married Marta Montañez, his Puerto Rican pupil, a woman of remarkable talent, intelligence, and charm; her devotion to Don Pablo was a constant source of comfort throughout his life. As a result, his relationship with Puerto Rico, his mother’s birthplace, became even more intense. The newly married couple settled in San Juan, where they instituted the Pablo Casals Festivals, which, like the Prades Bach Festivals, attracted the world’s musical elite. Casals died in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, in 1973.

Many of the major twentieth-century composers were characterized by their defiance of traditional musical concepts, whether by taking tonality and rhythm to the very limit or by venturing into the virtually unexplored areas of polytonality and atonality. Casals’s taste in music, however, was well defined. For him music meant only tonal music, in which the melody plays a distinct, fundamental role. Therefore, he harshly criticized most of the leading composers of his time.

We can only regret the fact that Casals refrained from fostering and promoting the composition of cello works, a task that would have been easy for him to accomplish, either directly or through musical organizations that would have enthusiastically supported these projects.

Feuermann was one of the greatest virtuosos of the twentieth century. He was born in Kolomea, Ukraine, in the bosom of a musical family, but from his early childhood he lived in Vienna.

Feuermann first studied with his father, and subsequently with, among others, the famous Julius Klengel. In 1929 he was appointed Hugo Becker’s successor in Berlin’s Akademische Hochschule für Musik (Academic University of Music), where he remained until 1934, when the alarming political situation in Germany drove him to immigrate to the United States.

Feuermann’s technical perfection, exquisite tone, and elegant interpretations are truly legendary. The young Emanuel grew in the shadow of Pablo Casals, about whom he said, “No one who has heard him play can doubt that a new period for the cello began with him . . . He has been an example for younger cellists and he has demonstrated . . . that to listen to the cello can be an extraordinary artistic delight.”8

However, Feuermann’s refinement of the cello technique attained new and unprecedented heights. It is possible that the example of his eldest brother, who also played the violin, and his contact with a series of outstanding violin virtuosos convinced Feuermann that the cello could be played with the same purity and perfection as the violin, with the same impeccable technique, ease, and passion that Heifetz displayed on the violin. The hugely successful collaboration between the two artists, Feuerman and Heifetz, is reflected by the recordings they made together: Brahms’s Double Concerto, with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra; Mozart’s Divertimento, and Dohnányi’s Serenade op. 10, both with William Primrose on the viola; and trios by Beethoven, Brahms, and Schubert, with Artur Rubinstein on the piano.

In the spring of 1938, Feuermann gave a series of four concerts at Carnegie Hall with the National Orchestral Association. The unprecedented program featured a sizeable part of the repertoire for cello and orchestra from the eighteenth century to 1932.

Feuermann’s career flourished, and would have attained dazzling heights if a tragedy—an infection following a routine surgical procedure—had not ended his life in 1942, at the age of thirty-nine. If we bear in mind that Casals turned thirty-nine in 1916, the year of his earliest recordings (several now forgotten salon pieces) and that he lived another fifty-nine years, we can better appreciate the dreadful loss that the death of Emanuel Feuermann, one of the greatest figures in the history of the cello, meant to the world.

Piatigorsky was not only one of the great cellists of the twentieth century, but was also a highly charismatic figure. His personality, sense of humor, and joie de vivre were particularly appreciated in his adopted country, the United States, where he was most successful in promoting and popularizing the cello repertoire.

Born in 1903 in Ekaterinoslav, in southern Ukraine, he started studying the cello at the local conservatory at the age of seven. When the family moved to Moscow, “Grisha,” who was barely nine, was awarded a scholarship to the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied with Professor Alfred von Glehn, a student of the famous Davidov. Despite his young age, Grisha found a job as a cellist to help with his family’s financial problems. He performed in nightclubs—where he sat with his back to the audience to prevent him from looking at the scantily clad dancers—in cafés, and with second-rate bands that entertained patrons with all types of music.

He was fourteen when Lenin carried out his coup d’état in October 1917. Despite the turbulent times, Grisha always managed to find work. Before he turned fifteen he was offered the highly coveted position of first cello in the Bolshoi Theater Orchestra. He also joined a well-known string quartet, which, during that period of constant name changes, was renamed the Lenin Quartet. He had the opportunity to meet Lenin, who impressed him with his apparent unpretentiousness. “He spoke with a slight burr. There was nothing of the mighty revolutionist in his appearance. His manner of speaking was simple and mild. His jacket, his shoes were like those of a neighborhood tailor . . . He spoke in parables, not touching big topics. But whatever he said was profoundly human and was said with disarming simplicity.”9

When Piatigorsky decided to emigrate in order to pursue his studies in either France or Germany, he had an interview with Anatoly Lunacharsky, the minister of education, who denied him the necessary permit. While on tour with the Bolshoi Ballet, Piatigorsky decided to defect in Volochisk, a village on the Polish border (now in the Ukraine). In the middle of the night, just as he was about to cross the bridge bordering the Zbruch River, he heard gunshots coming from both sides of the border. Piatigorsky waded into the shallow waters, holding his cello above his head, and managed to reach Poland.

In Berlin Piatigorsky studied with the famous Hugo Becker, and in Leipzig with the equally famous Julius Klengel. Word of Piatigorsky’s increasing reputation as a musician had reached Wilhelm Furtwängler, conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, who invited him to audition. Furtwängler was so impressed that he immediately offered Piatigorsky the position of principal cellist. It was around this time that Piatigorsky was introduced to the Mendelssohn family, especially Francesco, and to the Piatti. His heavy concert schedule as a soloist forced him to resign from the Berlin Philharmonic after four years.

In 1929 Piatigorsky embarked on his first—and highly successful—tour of the United States and recorded Schumann’s concerto in London, thus consolidating his remarkable musical career. During the late 1930s, Piatigorsky, like many other European musicians, became an American citizen, and he moved to Los Angeles.

Piatigorsky’s fascination with contemporary music generated a considerable number of commissions and world premieres, such as the concertos by William Walton, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Paul Hindemith, Vladimir Dukelsky, Ildebrando Pizzetti, as well as Bloch’s Schelomo, among others.

His friendship with Prokofiev culminated in the Cello Concerto, op. 58. The cellist Lev Berezovsky premiered it in Moscow in November 1938, but according to Sviatoslav Richter, the premiere was “a complete failure.”10 When Piatigorsky premiered it in the United States, with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sergey Koussevitsky, he wrote to the author, pointing out several of the weak spots in the piece and suggesting certain changes.

Although Igor Stravinsky did not compose any pieces for the cello, Piatigorsky persuaded him to adapt part of his orchestral suite Pulcinella for cello and piano. Piatigorsky himself collaborated with Stravinsky on the transcription, entitled Suite italienne. Prior to sending the finished manuscript to press, Stravinsky suggested they draw up a royalty contract and offering to share half of the royalty payments with Piatigorsky, who refused, since he felt that the percentage offered was much too generous. Stravinsky then explained his proposition in detail:

“I am not convinced you understand. May I repeat again: fifty-fifty, half for you, half for me. You see, it’s like this: I am the composer of the music, of which we both are the transcribers. As composer I get ninety per cent, and as the arrangers we divide the remaining ten per cent into equal parts. In total, ninety five per cent for me, five per cent for you, which makes fifty-fifty.” Chuckling, I signed the contract. Since then I have shied away from fifty-fifty deals, but I continue to love Stravinsky’s music and to admire his arithmetic.11

In 1961 Heifetz and Piatigorsky founded the Heifetz-Piatigorsky Concerts, dedicated to chamber music. They frequently performed in Los Angeles and New York and made numerous recordings with such illustrious musicians as Artur Rubinstein, William Primrose, and Leonard Pennario, to name only a few. Piatigorsky was also devoted to academic activities, mainly in such prestigious institutions as the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, Boston University, the Tanglewood Festival, and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Rostropovich is a virtuoso with a supreme mastery of the instrument, a conductor, and a total musician, but driven by his enthusiasm for contemporary music, he has also promoted a remarkable number of works that have enriched the cello repertoire.

Mstislav Rostropovich was born in 1927 in Baku, the capital of what was then the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan. His first teacher was his father, Leopold, a distinguished cellist, who in his youth had studied with Pablo Casals. When he was sixteen, young “Slava”—the nickname for “Mstislav”—enrolled in Semyon Kozolupov’s class at the Moscow Conservatory.

In 1947, at the age of twenty, Slava had the audacity to play Prokofiev’s Cello Concerto, op. 58, a piece that did not quite satisfy the composer and had been the target of unanimous criticism in the ussr (at its premiere, nine years earlier) for its so-called ideological bourgeois content. The composer was so delighted with Rostropovich’s interpretation that he promised to rewrite the concerto, although he first composed his Sonata for Cello and Piano, op. 119. In 1949, when the sonata was completed, he invited Slava to his dacha in Nikolina Gora, near Moscow, so they could play and revise it together, thus marking the beginning of an intense though brief collaboration that was cut short by Prokofiev’s death in 1953. Rostropovich spent two summers with Prokofiev and his wife, Mira, in Nikolina Gora, where they rewrote the concerto together. The new version, the Symphony-Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, op. 125, dedicated to Slava himself, was concluded in 1952. A truly magnificent work, it now forms part of the standard twentieth-century cello repertoire.

In 1955 Rostropovich married the great soprano Galina Vishnev skaya, whom he often accompanied, either on the piano or as conductor of the opera orchestra of the Bolshoi Theater. He had embarked on a conducting career in 1961 with the Nizhny Novgorod orchestra and then with the Bolshoi Ballet.

On August 2, 1959, Shostakovich presented him with an extraordinary gift: the recently completed Concerto in E-flat Major for Cello and Orchestra. Slava then withdrew to his house, where he studied it all the way through almost without a break. On August 6, he and pianist Alexander Dedyukhin set off for Shostakovich’s dacha in Komarovo, near Leningrad, to play the concerto for the composer. When Shostakovich offered to bring him a music stand, Slava replied that it wasn’t necessary since he had learned the piece by heart. “Th at’s impossible, impossible!” Shostakovich exclaimed, but Rostropovich sat right down and played the entire concerto during what turned out to be a truly memorable session in the presence of the composer and the small group of friends he had invited to hear his composition performed for the first time.12 It is certainly one of the most glorious cello concertos of the twentieth century.

In 1955, the Soviet government started allowing its most distinguished artists to travel to the West. Almost overnight, Rostropovich became an international celebrity. His passion for contemporary music had already borne fruit in his own country, and it proved to be an effective catalyst for the creation of new cello compositions. Benjamin Britten’s five works for cello were all written for Rostropovich: the Sonata for Cello and Piano, the Symphony for Cello and Orchestra, and the three Suites for Solo Cello. Since I cannot possibly name every composer who wrote works for him, because the list would be much too long, I will only mention Witold Lutoslawski, Krzysztof Penderecki, Henri Dutilleux, Henri Sauguet, André Jolivet, Cristóbal Halffter, Lukas Foss, Leonard Bernstein, Alberto Ginastera, Olivier Messiaen, Alfred Schnittke, Pierre Boulez, and Luciano Berio.

In spring of 1968, when Rostropovich gave a concert in Kazan with the Moscow Symphony Orchestra, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and his wife, Natalia, were in the audience. The next day, the cellist, who had never met Solzhenitsyn, unexpectedly showed up at the writer’s house, and introduced himself: “I am Rostropovich. I have come to embrace Solzhenitsyn.”13

A short time later, he learned that Solzhenitsyn, who was living in Rozhdestvo at the time, had fallen ill. With his characteristic impulsiveness, Rostropovich immediately got in his car and drove to Rozhdestvo. When he realized that the writer, suffering from an acute case of sciatica, was cooped up in a cold damp cottage, Rostropovich promptly invited the Solzhenitsyns to spend the winter at his property at Zhukovka, where he had just built a small guesthouse. It was then that Rostropovich started having problems that at first seemed to be nothing more than the usual bureaucratic red tape.

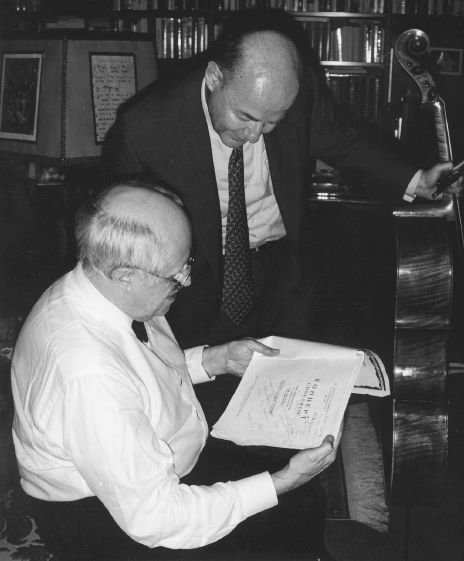

51. With Rostropovich in Mexico City, 1994, examining the score of Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1.

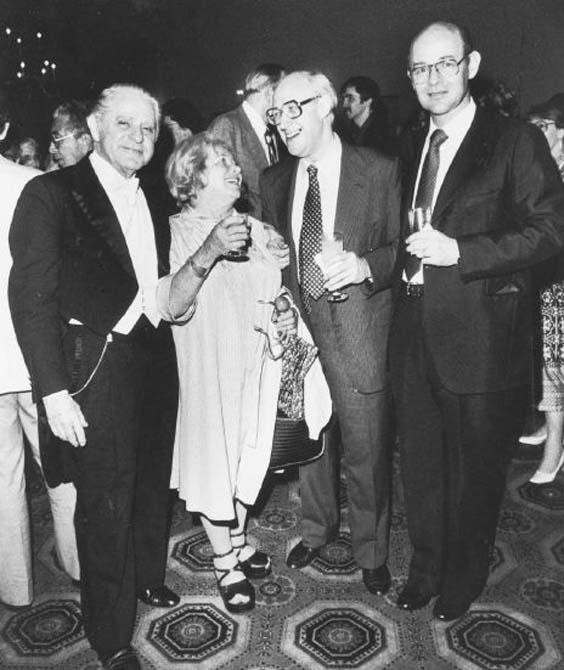

52. Rostropovich and the Prieto Quartet, Mexico City, 1994. LEFT TO RIGHT: Carlos Miguel Prieto, Juan Luis Prieto, Mstislav Rostropovich, Carlos Prieto, and Juan Luis Prieto, Jr.

When Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970 and the media unleashed a virulent campaign against him, Rostropovich was reminded of the times when Stalin’s henchmen had attacked Shostakovich and Prokofiev and no one had dared to speak out in their behalf.

Rostropovich sent a letter to the main Soviet newspapers in defense of the writer. The reactions were not long in coming. Invitations to conduct the Bolshoi Opera were inexplicably withdrawn, and requests for concert tours abroad and performances with the major orchestras dwindled considerably, for no other reason than the usual lame excuses and stumbling blocks.

Finally, Galina placed her own career in jeopardy by proposing that she and Slava write a letter to Brezhnev and request permission to leave the ussr. Brezhnev agreed, and in the spring of 1975, Slava, Galina, and their two daughters departed for what was officially described as a two-year trip “for artistic purposes.”

In the West, Rostropovich continued his work as the driving force behind the creation of new works for cello and new orchestral pieces, since, though never abandoning the cello, he was devoting more time to conducting. In 1977, he was appointed musical director of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, where he remained until 1994.

In 1978, because of their “anti-Soviet activities,” Galina Vishnevskaya and Mstislav Rostropovich—two artists who had garnered extraordinary prestige and glory for their country—were stripped of their Soviet citizenship by the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

In 1985, however, the situation began to change when Gorbachev came to power. Five years later in Moscow, Rostropovich and Galina received an enthusiastic welcome from the people and the Soviet government when Rostropovich returned for a concert tour as conductor and soloist with the National Symphony Orchestra.

In 1991, as soon as he heard of the coup that threatened to crush Gorbachev’s reforms and remove Boris Yeltsin as president of the Russian Republic, Rostropovich took the first plane to Moscow. A photograph of Rostropovich standing in front of the Russian “White House,” joining forces with the thousands of protestors opposing the coup by defying the Russian army’s tanks, was published around the world. It was this gesture, along with his long struggle in defense of human rights in Russia, that subsequently earned him the State Prize of Russia.

I met Rostropovich in 1959 when he came to Mexico for the first Pablo Casals Music Festival and the Second International Cello Competition in Veracruz. We were introduced by Vladimir Wulfman and violinist Luz Vernova, friends we had in common, at his concert in Mexico City. At that time, Rostropovich was thirty-three and very slender, exuding the same energy he still does today. When Luz Vernova mentioned that I played the cello, Rostropovich invited me to his dressing room and took out his cello. “What movement from Bach’s Suites would you like to hear?” he asked. “The gavotte from the sixth suite,” I answered. He played this movement, as well as the gigue from the same suite. The session was cut short because he had a previous engagement at the Soviet Embassy. I drove him there myself, and after a few glasses of vodka, he caused a sensation by playing a piece on the piano. Rostropovich happens to be an excellent pianist, but what really brought down the house was that he played the piece from three different positions: sitting in front of the piano, sitting with his back to the piano, and, finally, lying under the piano.

In May 1994, we spent considerable time with Slava when he was in Mexico during the four concerts he played in the Palace of Fine Arts. After a Sunday concert, we invited him to a luncheon at our home with what was supposed to be a small group of friends and family. However, the group increased considerably as friends of Slava’s started arriving at the last minute. Before Slava left, he wanted to meet the Piatti, and he played it for quite awhile. Neither his pulse nor intonation ever hinted at the not inconsiderable amounts of vodka and tequila he had imbibed (Figs. 51 and 52). Rostropovich’s vitality and energy are boundless, as are his invaluable contributions to the cello and to the world of music itself.

Yo-Yo Ma is an extraordinary and unique case of talent, personality, and charisma. His multifaceted activities have drawn unprecedented attention to the cello while enriching music in many ways and building bridges of understanding across cultures throughout the world.

Yo-Yo Ma was born in 1955 in Paris to Chinese parents; when he was four, he started studying the cello with his father. His family moved to New York in 1962, and after studying with János Scholz, Yo-Yo, barely seven, became Leonard Rose’s pupil at Juilliard. While a teenager, he was already being compared to Casals.

Besides keeping a hectic concert schedule as a soloist with the principal orchestras of the world, Yo-Yo is also intensely devoted to chamber music, recording with colleagues and friends such as Isaac Stern, Jaime Laredo, Emanuel Ax, and others. With Emanuel Ax he has created one of the most extraordinary duos of our times, offering frequent recitals and recording the standard repertoire for cello and piano.

Contemporary music plays a fundamental role in Yo-Yo Ma’s career. Over the past few years, he has premiered countless works for cello and orchestra. Most of these pieces, the result of his active collaboration with the composer, have been dedicated to him. He has premiered pieces for cello and orchestra composed by William Bolcom, Ezra Laderman, David Diamond, Peter Lieberson, Tod Machover, Stephen Albert, Leon Kirchner, John Harbison, Christopher Rouse, and Richard Danielpour, to name only a few.

Obviously, his interest is not restricted to works by American composers. In 1997, for example, he premiered a piece commissioned for him from Chinese composer Tan Dun, on the occasion of Hong Kong’s reintegration with China. His exploration of music from the Silk Road region has resulted in a series of fascinating musical experiences.

Yo-Yo Ma’s successful forays into other musical genres are borne out by his jazz recordings with Claude Bolling; Hush, with Bobby McFerrin; Appalachia Waltz, with Mark O’Connor and Edgar Meyer; and recordings of tangos and Brazilian music. He has immersed himself in Chinese music played on native instruments and in the music of the Kalahari bush people in Africa.

Yo-Yo Ma also devotes a great deal of time to master classes and informal contacts with young musicians, as well as to frequent television appearances, both in concerts and on educational programs.

I met Yo-Yo Ma in 1983 in New York during a tribute for our teacher, Leonard Rose. Since then, we have seen each other a number of times, and I am always impressed not only by his extraordinary musical talent, but also by his charm, intelligence, and kindness.

In 1993 we had the pleasure of having him as our houseguest in Mexico, along with his wife Jill and their small children, Nicholas and Emily. The children, eight and six years old, respectively, were every bit as delightful as their parents. María Isabel, my wife, who one day accompanied Jill, Nicholas, and Emily on the obligatory visit to the pyramids in Teotihuacan, was amazed at Nicholas’s perceptive questions, although, given his parents, his precocity came as no surprise. Unlike many of my colleagues who are extremely knowledgeable about music but very little else outside their field, Yo-Yo is interested in a wide variety of subjects. He studied history at Harvard University, and since he was born in France and his parents are Chinese, speaks French and Mandarin, and is very familiar with Chinese culture. Although Yo-Yo, who lives with his wife and children in Cambridge, a few steps from Harvard, is a U.S. citizen, he is, in fact, a citizen of the world.

The day they toured Teotihuacan, the four Mas were invited to dinner at our house in San Angel. Yo-Yo arrived with his Stradivari, the famous 1712 Davidov, and I had the privilege of playing some duets with him. While we were at the table, we left the two Stradivari cellos alone in the music room, outside of their cases. Yo-Yo thought that perhaps they might fall in love and produce some “Stradivari babies.” I described the outcome of the meeting of the two Strads in Chapter 5.

English-born Du Pré’s meteoric career—and life—were cut short by multiple sclerosis. Her legendary recording of Elgar’s Concerto catapulted her into musical stardom in 1965. Married to pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim, they were among the most celebrated couples in the history of music.

In Chapter 3 I described the career of this brilliant Spanish cellist, composer, and teacher, who played the Piatti for some time. Further on, in the section devoted to twentieth-century cello works, readers will find comments on his work as a composer.

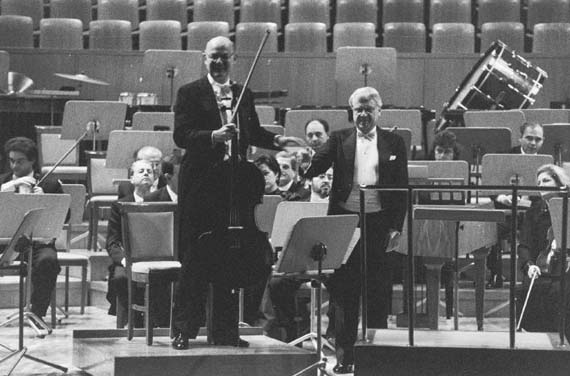

53. With cellists Leonard Rose, Raya Garbousova, and Mstislav Rostropovich at the University of Maryland, 1981.

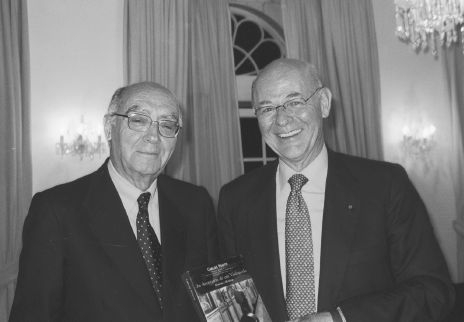

54. After receiving the Chevalier du Violoncelle award, presented by the Eva Janzer Memorial Cello Center of Indiana University. With fellow cellists Janos Starker (LEFT) and Tsuyoshi Tsutsumi (RIGHT), Bloomington, 2001.

Fournier, who studied at the Paris Conservatory, performed with the greatest conductors of his time—Furtwängler, Rafael Kubelik, and Herbert von Karajan, among others. In addition to his incomparable recordings of the principal works in the cello repertoire, he premiered Poulenc’s Cello Sonata, Martinu’s Cello Concerto no. 1, and other works dedicated to him. He participated in numerous trios with violinist Henryk Szeryng and pianist Artur Rubinstein, and taught at the École Normale de Musique (a training college for music teachers) and later at the Paris Conservatory. I knew him well, since he was my teacher in Geneva in 1978.

Rose, born in Washington, D.C., was one of the most distinguished American cellists and teachers of the twentieth century (see Fig. 53). Principal cellist for orchestras in Cleveland and New York, as well as the nbc Orchestra, he subsequently devoted all his time to his career as a soloist and as a teacher at Juilliard, where he taught such celebrated musicians as Yo-Yo Ma, Lynn Harrell, and Stephen Kates. He was also a member of the Stern-Rose-Istomin Trio. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have studied with him in New York.

Starker, one of the great virtuosos of the twentieth century, studied music in his native Budapest. In 1948, he immigrated to the United States and became principal cellist of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. Since 1958 he has devoted all his time to his twofold activities as an international soloist and a teacher. He has premiered numerous works dedicated to him; he has made over 150 recordings of the most varied cello repertoire; he is a faculty member at Indiana University’s School of Music in Bloomington.

On October 20, 2001, Janos Starker, the iu School of Music, and the Eva Janzer Memorial Cello Center presented me with the Chevalier du Violoncelle award, an honor for which I am profoundly grateful (see Fig. 54).

Brazilian-born Aldo Parisot has had an extremely brilliant career as a soloist and as a teacher, especially at Juilliard, Yale, and countless international festivals and seminars. Aldo Parisot is a permanent member of the judges panel for the Carlos Prieto Cello Competitions, described in Chapter 6. We owe him an enormous debt for his invaluable contributions.

Appendices 1 and 2 include charts listing the principal cello works of this period. The first chart comprises 337 works by 129 European, U.S., and Japanese composers. The second chart lists 425 works by 189 composers from Latin America, Spain, and Portugal; it is particularly extensive because, as far as I know, a list of cello works by composers from these regions has never before been published.

On the following pages, I will refer to only a few of the fundamental works of the twentieth-century cello repertoire (the lists are in alphabetical order by country). It would be pointless for the charts in the appendices to include an exhaustive list of compositions, since the concept of what constitutes an “important” work is highly subjective and relative. For example, there may be certain works worth mentioning that I know nothing about, whereas some that appear on the list may not withstand the test of time, and soon be forgotten.14

AUSTRIA Anton Webern (1883–1945) was an active cellist while he was a student. In his youth he composed Two Pieces for Cello and Piano (1889), the Sonata for Cello and Piano (1914), and Three Small Pieces for Cello and Piano (1914), all distinguished for their conciseness and concentration. The Three Small Pieces consist of, respectively, only nine, thirteen, and twenty measures.

Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) was also a cellist in his youth. In 1914 he published an edition of the Concerto in G Minor for Cello by the Viennese composer Georg Matthias Monn (1717–1750); from 1932 to 1933 he made an arrangement for cello and orchestra of Monn’s Concerto for Harpsichord in D Major.

BELGIUM The great violinist Eugène Ysaÿe (1858–1931) was profoundly familiar with the cello, as can be seen in his Poem for Cello and Orchestra, op. 16, and in his Sonata for Solo Cello, op. 28 (1924).

CZECHOSLOVAKIA A dominant figure of twentieth-century Czech music was Bohuslav Martinu (1890–1959), a prolific composer who left numerous works for the cello: two concertos for cello and orchestra, three sonatas for cello and piano, and a series of variations and minor works, of which the most outstanding is his Variations on a theme by Rossini.

Leoš Janá ek (1854–1928) composed Prohadka, (Fairy Story) for cello and piano in 1910.

ek (1854–1928) composed Prohadka, (Fairy Story) for cello and piano in 1910.

ENGLAND For almost a century and half after Purcell and Handel, England had no composers comparable to those on the European continent. It was not until the end of the nineteenth century that Great Britain began to experience a remarkable musical renaissance. A wide range of British composers have enriched the cello repertoire with numerous works; so numerous, in fact, that here I will mention only four composers whose contributions have proved especially valuable: Delius, Elgar, Walton, and Britten.

Frederick Delius (1862–1934) composed several noteworthy works for the cello: Romance for Cello and Piano (1896), Double Concerto for Violin, Cello, and Orchestra (1916), Sonata for Cello and Piano (1917), Capriccio and Elegy for Cello and Orchestra (1925), and Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (1921).

The Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (1919) by Edward Elgar (1857–1934) is one of the last great Romantic concertos.

In 1956 William Walton (1902–1983) composed his cello concerto, which, as we have seen, was dedicated to Gregor Piatigorsky. It consists of three parts: a melodious Moderato, an Allegro appassionato—resembling a scherzo filled with rhythmic energy—and a Theme with Variations.

Another composer who bequeathed an invaluable legacy for the cello was Benjamin Britten (1913–1976). Inspired by his friendship with Rostropovich, he created five great, original, and imaginative works, all dedicated to the great Russian musician: Sonata for Cello and Piano, op. 65 (1961), the Symphony for Cello and Orchestra, op. 68 (1963), and Three Suites for Cello Solo, opp. 72 (1964), 80 (1968), and 87 (1971).

FINLAND The best known figure in Finland’s music world is Jean Sibelius (1865–1957). Whereas his violin concerto is one of the principal works of that genre, his compositions for the cello, such as his Malinconia for cello and piano (op. 20), are minor works.

His compatriot, Leif Segerstam (b. 1944,) a world-renowned composer and conductor, is also a pianist, violinist, and one of the most interesting figures in contemporary Scandinavian music. One of the most prolific composers of our time, he has written twenty-nine quartets, seven concertos for cello and orchestra, and twenty-four symphonies.

FRANCE No reference to twentieth-century French compositions for cello would be complete without mentioning the magnificent sonata for cello and piano written in 1915 by Claude Debussy (1862–1918). That same year Debussy announced that he was composing a series of six instrumental sonatas entitled Six sonates pour divers instruments composées par Claude Debussy, Musicien français. He actually completed only three, including the cello sonata (1915). The sonata for cello is an original work in all respects: form, themes, sound, and innovative effects. Its three movements—Prologue (lent), Sérenade (fantasque et léger), and Finale (animé, léger et nerveux)—are so varied and create such diverse moods that it is hard to believe it lasts only ten minutes!

The two sonatas (1918 and 1922) by Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924) contain music of great beauty. They could be compared to two paintings rendered in pastel tones, completely devoid of harsh colors and flamboyant effects. These pieces, of indisputable musical merit, were not written to allow instrumentalists to display their virtuosity, and they are not performed as often as they deserve. However, some of his short pieces for cello and piano now occupy a solid position in the standard repertoire. I will mention them here, although they were composed at the end of the nineteenth century: Elégie, op. 24 (1883), Papillon, op. 77 (1898), and Sicilienne, op. 78, also from 1898.

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) composed a wonderful Sonata for Violin and Cello (1920–1922). It was premiered in 1922 by violinist Hélène Jourdan-Morhange and Maurice Maréchal, an eminent cellist of the first half of the century.

Maréchal, in fact, premiered several noteworthy compositions from the French cello repertoire. André Caplet (1892–1925) composed a symphonic fresco for cello and orchestra, entitled Épiphanie, and the particularly demanding solo part was first played by Maurice Maréchal in 1922.

Arthur Honegger (1892–1955) composed a sonata for cello and piano and a concerto for cello and orchestra that he dedicated to Maréchal. The concerto, a modest work lasting fifteen minutes, calls for a small orchestra. Its mood is lighthearted, in the manner of a divertimento, with touches of jazz.

Darius Milhaud (1892–1974) was an extremely prolific composer. The most noteworthy of his cello works is the Concerto no. 1, op. 136, also dedicated to Maréchal. It is truly a fun piece to play, typical of its author. The concerto begins with a cadenza for solo cello, and the somber, solemn tone turns into a fox-trot as soon as the orchestra joins in. Its three movements (Nonchalant, Grave, Joyeux) barely last fourteen minutes.

The sonata by Francis Poulenc (1899–1963), completed in 1948, was dedicated to Pierre Fournier, who assisted him with the technical aspects of the cello part, since the composer was unfamiliar with the instrument. The four movements of this magnificent sonata are Allegro (tempo di marcia), Cavatine, Ballabile, and Finale.

The Concerto for Cello and Orchestra entitled Tout un monde lointain . . . (A Whole Distant World) by Henri Dutilleux (b. 1916) is, in my opinion, one of the great cello masterpieces of the late twentieth century (see Chapter 5 for a more detailed account of this work). As I mentioned earlier, during its long gestation process, Dutilleux happened to be immersed in Baudelaire’s works. Each of its five movements is inspired by poems from Les fleur du mal (Flowers of Evil). The work was performed in public for the first time during the Aix-en-Provence Festival on July 25, 1970, with Mstislav Rostropovich as soloist.

GERMANY Among the important twentieth-century cello works that I know of are the three suites for cello solo by Max Reger (1873–1916). Dated 1915, they were based on Bach’s suites. Paul Hindemith (1895–1963) composed several works for the cello, such as his Sonata for Solo Cello, op. 25, no. 3 (1923), Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (1940), and Sonata for Cello and Piano (1948). Bernd Alois Zimmermann (1918–1970) made significant contributions to the cello repertoire with works for solo cello, cello and piano, and cello and orchestra, several of them dedicated to Siegfried Palm, a champion of contemporary music.

HUNGARY During the first half of the twentieth century, Hungary’s musical panorama was dominated by the figure of Béla Bartók (1881–1945). Unfortunately, Bartók’s only work for cello and piano was not even originally conceived for the cello, since it is his own transcription of his First Rhapsody for Violin and Piano.

However, Zoltán Kodály (1882–1967), Bartók’s companion and colleague, has left us several major works for the cello, such as the incomparable Sonata for Cello Solo, op. 8, a work that takes full advantage of the instrument’s tonal and expressive potential; a Sonata for Cello and Piano, op. 4 (1909–1910), and a Duo for violin and cello, op. 7.

During the second half of the century, the predominant figure was György Ligeti (b. 1923), who immigrated in 1956 to Austria, and then to Germany. In Chapter 5, I describe his Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, composed in 1966.

ITALY Ottorino Respighi (1879–1936) composed Adagio with Variations for cello and orchestra in 1920, a piece in the neoclassical style, now fully incorporated into the contemporary repertoire.

Alfredo Casella (1883–1947) wrote several works for the cello: two sonatas with piano, a concerto for cello and orchestra (1934–1935), and a triple concerto for violin, cello, piano, and orchestra. His Cello Sonata no. 1, op. 8 (1906), a clear, melodious work, is dedicated to Pablo Casals.

Luigi Dallapiccola (1904–1975) left us two compositions: Ciaccona, intermezzo e adagio (1945) for solo cello and Dialoghi (1959–1960) for cello and orchestra, both dedicated to Gaspar Cassadó.

More recently, Luciano Berio (1925–2003) composed Il ritorno degli Snovidenia (1976–1977) for cello and instrumental ensemble and Les mots sont allés . . . (1976–1978) for solo cello.

Precisely during the period when artistic expression in countries in the orbit of the Soviet Union was stifled by the shackles of socialist realism, Poland was experiencing an extraordinary musical renaissance and turning into an important forum for contemporary music.

Witold Lutoslawski (1913–1994) composed a remarkable cello concerto (1970), mentioned in Chapter 6, and the Sacher Variation (1975) for solo cello.

Krzysztof Penderecki (b. 1933) is the author of two concertos for cello, the first (1972) dedicated to Siegfried Palm and the second (1982) to Yo-Yo Ma. He also composed a concerto for three cellos and orchestra and the Capriccio per Siegfried Palm (1968) for solo cello.

There are numerous cello compositions written by composers from Russia and from several nations that were once part of the ussr. During the second half of the twentieth century, they were, for the most part, inspired by Mstislav Rostropovich. As I pointed out earlier, we will only present a brief overview of the most important works.

Sergey Rachmaninov (1873–1943) composed his Sonata in G Minor for cello and piano, op. 19 (1901), immediately before beginning work on his second piano concerto. The sonata, filled with rich melodic content, is typical of the composer at the height of his creative power. Although its diverse themes are highly suited to the nature of the cello, the fact that the composer was a virtuoso pianist means that he occasionally allows the piano to dominate the work. Nevertheless, this sonata is one of the important cello pieces of the century and, certainly, one of the most beautiful.

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) was born in Russia but emigrated prior to the Russian Revolution. His only cello composition is the Suite italienne for cello and piano, a transcription he and Gregor Piatigorsky made of a ballet suite from Pulcinella.

Among the most outstanding cello works composed by Sergey Prokofiev (1891–1953) are his Sonata in C Major for cello and piano, op. 119 (1949), and hisSymphony-Concerto, op. 125 (1950–1951), whose origins were discussed earlier. Both works were dedicated to Rostropovich.

Aram Khachaturian (1903–1978), an Armenian, studied the cello at the Gnessin Music Academy in Moscow. Apart from some juvenile works, his main compositions for the cello include a concerto for cello and orchestra (1946), the Concerto-Rhapsody for cello and orchestra (1963), and the Sonata-Fantasy for solo cello (1974).

Dmitry Kabalevsky (1904–1987) wrote several works for the cello, including two sonatas for cello and piano and two concertos for cello and orchestra. The first concerto (1948–1949), dedicated to youth, is a light and well-accomplished work.

Dmitry Shostakovich (1906–1975), a legendary—though highly controversial and complex—figure, is now viewed in a new light. His operas—once so disputed—symphonies, concertos, and countless chamber works are now an essential part of the standard music repertoire.

His three cello compositions have earned a well-deserved place among the principal cello works of the twentieth century: the Sonata for cello and piano, op. 40 (1964), and the Concertos no. 1, op. 107 (1959) and no. 2, op. 126 (1966).

Moishei Vainberg (1919–1996) was born in Poland as Mieczyslaw Weinberg, but is better known as Moishei Vainberg, since he spent most of his life in Russia, where he composed all his works. Highly regarded by Shostakovich, he is only now beginning to be recognized as an outstanding composer. He composed twenty-two symphonies, seventeen string quartets, seven operas, and numerous cello works, including four sonatas for solo cello, two sonatas for cello and piano, twenty-four preludes for solo cello, and two cello concertos.

Of the post-Shostakovich generation, there are three especially noteworthy composers: Edison Denisov, Sofia Gubaidulina, and Alfred Schnittke, who all took advantage of the new freedoms in Russia and chose to immigrate (Denisov to France, Gubaidulina and Schnittke to Germany).

Edison Denisov (1929–1996), a Siberian, composed many cello works: a sonata for cello and piano (1971), three pieces for cello and piano (1967), and a cello concerto (1972).

Sofia Gubaidulina was born in 1931 in Chistopol in the Tatar Republic of the Soviet Union and lived in Moscow until 1992. Since then, she has made her permanent home near Hamburg. She too has composed numerous cello works: two concertos, two pieces for cello and small ensembles, ten preludes for solo cello (1974), and various compositions for cello and piano.

Alfred Schnittke (1934–1998), a remarkable composer, is the author of two concertos for cello and orchestra; a triple concerto for violin, viola, cello, and orchestra; the Dialogue for cello and seven instruments; and two sonatas for cello and piano.

Sulkhan Tsintsadze (1925–1991) was, along with Giya Kancheli (b. 1935), perhaps the most celebrated composer in Soviet Georgia. Tsintsadze studied the cello during his years at the conservatory in Tbilisi. His numerous cello works include three cello concertos (1947, 1963, and 1974) and a collection of twenty-four preludes for cello and piano (1980). Kancheli composed Simi (Joyless thoughts) for cello and orchestra (1995).

In the twentieth century, the two most outstanding composers from this country were Ernest Bloch and Frank Martin.

The most frequently played cello piece by Bloch (1880–1959) is Schelomo: Hebraic Rhapsody for Cello and Orchestra (1915–1916), one of his finest, most eloquent compositions. In this piece, the solo cello represents the feelings and passions of King Solomon (Schelomo in Hebrew.) Bloch composed a minor work for cello and orchestra entitled A Voice in the Wilderness (1936), as well as three suites for solo cello (1956, 1956, and 1957).

Frank Martin (1890–1974) wrote a concerto for cello and orchestra (1966), dedicated to Pierre Fournier, that is also worth mentioning.

Arthur Honegger was born in Switzerland, but since spent most of his life in France and is therefore more identified with French composers, I discuss his work in the section (above) devoted to France.

UNITED STATES The first cello concertos composed in the United States were by Victor Herbert (1859–1924), at approximately the same time (1884–1894) that Ricardo Castro was composing his concerto in Mexico.

Walter Piston (1894–1976) studied at Harvard and later in France with Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger. He then became an excellent teacher, whose best-known students were Elliott Carter and Leonard Bernstein. In 1966 he composed his Variations for Cello and Orchestra, dedicated to Rostropovich.

Elliott Carter (b. 1908.) composed a fundamental work in the cello music of the United States: his Sonata for Cello and Piano (1948). The sonata is extremely complex, especially in its rhythm. Carter exploits the different natures of both instruments by providing each with its own melodic content and even a separate tempo, thus creating the impression that both instruments are improvising independently from each other.

Samuel Barber (1910–1981) composed two excellent works for cello: Sonata for Cello and Piano, op. 6 (1932) and Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (1945), both Romantic or Neoromantic pieces supporting Barber’s theory that music should not be difficult to understand. Barber composed for himself, fully convinced that the public would ultimately appreciate good music. The difficult solo part of the concerto highlights the instrument’s lyrical quality.

Italian-born Gian Carlo Menotti (b. 1911) has composed the Fantasia for Cello and Orchestra and the Suite for Two Cellos and Piano.

Lukas Foss (b. 1922) was born in Germany, but immigrated to the United States in 1933. His many compositions include his picturesque Capriccio for Cello and Piano (1946), which is dedicated to Gregor Piatigorsky and is radically different from his Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, in which the soloist appears twice and one of the two cello voices is recorded on tape. Mstislav Rostropovich, to whom it is dedicated, premiered the work in 1967.

Leon Kirchner (b. 1919) composed his Music for Cello and Orchestra for Yo-Yo Ma, who took his course on performance and analysis at Harvard. Ma premiered in 1992 with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by David Zinman.

George Crumb (b. 1929) wrote a noteworthy piece for the contemporary U.S. repertoire. His Sonata for Cello Solo (1955), a dynamic, emotional work, lasts only ten minutes and requires the utmost technical mastery of the cello.

After studying at Harvard and Princeton, John Harbison (b. 1938) became a professor in mit’s Music Department, where he received the Killian Award (1994) for his “extraordinary professional achievements.” So far he has composed two works for cello: a Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (1993), premiered in 1994 by Yo-Yo Ma, Seiji Ozawa, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and a short Suite for Cello and Piano (1993).

Stephen Albert (1941–1992), who died tragically in an automobile accident in 1992, was one of the most acclaimed composers of his generation, having received two Rome Prizes, the Pulitzer Prize, and a Grammy, among many others. His music has solid roots in traditional composition techniques, and is characterized by a highly personal contemporary language. One of his last compositions was his Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra for Yo-Yo Ma.

The musical education of Robert X. Rodriguez (b. 1946) included classes with Hunter Johnson, Halsey Stevens, Jacob Druckman, and Nadia Boulanger, as well as master classes with Bruno Maderna and Elliott Carter. Rodriguez has been a “composer in residence” with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, among others. Among his recent works are Máscaras (a concerto for cello and orchestra) and Lull-a-bear for cello and piano. As detailed in Chapter 6, I premiered both: the first at the International Cervantes Festival at the end of 1994 and the second in Mexico City in 1995.

Christopher Rouse (b. 1949) composed his Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in 1992, calling it a “meditation on death, on the struggle to deny death and on the inevitability of death.” Commissioned for Yo-Yo Ma and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, it was premiered in 1994, with David Zinman conducting.

Richard Danielpour (b. 1956), originally from New York, is currently a professor at the Manhattan School of Music. Danielpour’s Concerto for Cello and Orchestra (1993) is dedicated to Yo-Yo Ma, who premiered it in 1994. It contains four movements: Invocation (arioso), Profanation (dance), Soliloquy, and Prayer and Lamentation (hymn).

As mentioned earlier, Appendix 2 includes 425 works by 189 composers from Latin America, Spain, and Portugal. I must stress once again that this list is not meant to be an exhaustive overview, since it will undoubtedly contain important omissions as well as works that will be eventually discarded by the passage of time.

Here, as in the case of the other countries, I will provide a summary of the principal works.15 In Chapter 6 I described my relationship with many of the composers from this region as well as many of the works I premiered.

ARGENTINA Alberto Williams (1862–1952) and Julián Aguirre (1868–1924), both representatives of the national Argentinean movement, composed the earliest cello works in that country. Williams, who studied in France with César Franck, wrote his Sonata for cello and piano, op. 52, in 1906.

Aguirre studied for some time in Spain with Albéniz. His only original work for cello and piano, a sonata in A Major, unfortunately remains an incomplete manuscript. His Rapsodia Argentina (1898) and Huella, op. 49 (1917), though not original works, are available in excellent transcriptions for cello and piano.

The sonata for cello and piano, op. 26 (1918), by Constantino Gaito (1878–1945) is a frequently played work in Argentina, and cellist Daniel Gassé has performed it in the United States.

Among the composers from the first half of the twentieth century, the Castro brothers—José María, Juan José, and Washington—must certainly be mentioned. José María Castro (1892–1964) and Washington Castro (1909–2004) were also cellists and the authors of several cello works listed Appendix 2. Juan José Castro (1895–1968) was the most influential of the brothers as a composer and teacher, but wrote only one sonata for cello and piano (1916). At Pablo Casals’s suggestion, Juan José Castro was appointed dean of the Puerto Rico Conservatory from 1959–1964.

Alberto Ginastera (1916–1983) is a predominant figure in Argentinean music. He composed six works for the cello, probably because his wife—now his widow—Aurora Nátola Ginastera, is a cellist. His Pampeana no. 2 for cello and piano (1950), which uses rhythms from the pampas, is a work I have often played, since I regard it as a jewel of the Latin American cello repertoire. Twenty-nine years later, Ginastera composed a new piece for cello and piano, the Sonata op. 49. His two concertos for cello and orchestra (1968 and 1980) are also important works.

For Astor Piazzolla (1921–1992), the reader can refer to Chapter 6, which includes a brief biographical sketch of the composer. Here I will add only that his original cello works are the Tres piezas breves for cello and piano, op. 4, composed in his youth, and the celebrated Le grand tango, one of his finest chamber works and one in which he combines a tango style with polytonal harmonies and clusters.

Several other composers, perhaps not as well known, are worth citing here. Hilda Dianda (b. 1925) has shown interest in the cello, and this has led her to write several pieces for the instrument. Although Werner Wagner (1927–2002) was born in Germany, his musical career took place in Argentina. His Rhapsody for cello and orchestra (1973, revised 1985) is well worth mentioning. Luis Jorge González (b. 1936) has composed two cello works: Oxymora (1973–1975) for cello and piano, and Confín sur (1995–1996), a suite for cello and piano. He is now composing a cello concerto.

Two recent orchestral works deserve to be mentioned here: the Rhapsody for cello and orchestra by Máximo Flugelman (b. 1945) and the Concertino for cello and string orchestra (1992) by Esteban Benzecry (b. 1970)

BOLIVIA Alberto Villalpando, born in La Paz in 1940, is probably the most important Bolivian composer of his generation. At the age of seventeen he moved to Buenos Aires to continue his piano and composition studies at the Carlos López Buchardo National Conservatory of Music, where he studied with Alberto Ginastera. I met him in La Paz in May 1999 when I gave a series of concerts and presented a previous edition of this book. In 1999 he composed the Sonatita de piel morena for cello and piano, dedicated to Edison Quintana and me.

BRAZIL Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887–1959), as prolific as the jungles of his native Brazil, composed over one thousand works in every conceivable musical genre. The cello was very special to him: he began studying it in childhood, and fully mastered it, as he did the guitar. In 1913 he wrote his first series of works for cello and piano, and his editor in Rio, Arthur Napoleão, dubbed them the Pequena suite. He wrote two sonatas for cello and piano (1915 and 1916), two concertos (1913 and 1953), and a fantasia for cello and orchestra (1945).

Perhaps his most important cello works, and certainly the most frequently performed, are the first and fifth of his Bachianas brasileiras. The concept behind this series of works was, in his own words, to combine a form “inspired by Bach’s musical ambiance” with diverse Brazilian musical effects. The first, dedicated to Casals, is for eight cellos, while the fifth is for soprano and eight cellos.

Camargo Guarnieri (1907–1993) was one of the principal exponents of Brazilian music, especially within the nationalistic school mentioned in Chapter 6. I will add only that his cello works include three sonatas for cello and piano (1931, 1955, and 1977), Chôro for cello and orchestra (1961), and Ponteio e dança (1946), in versions for cello and orchestra or cello and piano.

The music of Claudio Santoro (1919–1989) has been divided into three periods. From 1939 to 1947 his work tended toward the atonal and dodecaphonic (twelve-tone); between 1948 and 1960, his music leaned toward nationalism, in a style derived from Soviet theories about art. Finally, from 1960 to his death, Santoro returned to serialism and the use of aleatory techniques.

He did not compose any work for cello and orchestra. His works for cello and piano include four sonatas (1942–1943, withdrawn by the composer; 1947, 1951, and 1963) and an adagio (1946).

After obtaining his degree from the Pernambuco Conservatory, Marlos Nobre (b. 1939) studied in São Paulo with his compatriot Camargo Guarnieri and later in Buenos Aires with Ginastera. Nobre used the most diverse techniques in his compositions: aleatory music, free serialism, and a combination of rhythmic motifs and indigenous timbres. His cello compositions include Cantos de Yemanjá, op. 21, no. 3, for cello and piano; Desafío II (in three versions: for cello and string orchestra, for cello and piano, and for eight cellos), op. 31/32 (1968); the Partita latina for cello and piano, premiered and recorded by me in 2003; Poema III, op. 94, no. 3 (2002), for cello and piano; Cantoria I, op. 100, no. 1, for solo cello, dedicated to Antonio Meneses; and Cantoria II, op. 100, no. 2, for solo cello, dedicated to me.

José Antonio de Almeida (b. 1943), one of the preeminent composers of his generation, has composed a sonata for cello and piano (2003), premiered by the great Brazilian cellist Antonio Meneses.

CHILE For almost half a century, from the 1920’s to the late 1960’s, Domingo Santa Cruz (1899–1987)—composer, professor, founder of musical and educational institutions, and enthusiastic promoter of music—was the principal figure in Chilean music.16 His musical style is characterized by chromatic linearity and particularly rich counterpoint. His roots lie in the contrapuntists of the sixteenth century and in Bach, but his works also reflect Spanish rhythmic and melodic elements. His only contribution to the cello repertoire—but an important one—is his Sonata for cello and piano, op. 38 (1974–1975).

Juan Orrego-Salas (b. 1919) studied in his own country with Pedro Humberto Allende and Domingo Santa Cruz and then in the United States. He has played an active role as a composer, educator, and promoter of Ibero-American music and musicology. In 1961 he moved to Bloomington, where he taught at Indiana University’s Music School and founded the Latin American Music Center.

His relationship with the great cellist Janos Starker, also a teacher at Indiana, led to the creation of two works for the cello: the Balada for cello and piano, op. 84 (1982–1983), and the Concerto for cello and orchestra, op. 104 (1991–1992), both premiered by Starker. He has also composed Cantos de advenimiento for soprano, cello, and piano, op. 25 (1948), Dúos concertantes for cello and piano, op. 41 (1955), Concerto a tre for violin, cello, piano, and orchestra, op. 52 (1962), and Serenata for flute and cello, op. 70 (1972).

My conversations with Orrego-Salas ultimately resulted in Espacios, op. 115 (1998), a new piece for cello and piano. After the premiere in Santiago and Viña del Mar, we played it in Mexico, in South Africa, and at the Kennedy Center, during a concert honoring the composer, who was present. A few months later I received a most touching gift from Orrego-Salas, his Fantasias for cello and orchestra, with a lovely dedication; I expect to premiere the work in 2006.

Gustavo Becerra-Schmidt (b. 1925) studied at the at the Santiago National Conservatory, where he was assistant professor in Domingo Santa Cruz’s composition class. He was subsequently made full professor at the conservatory, and since 1950 he has devoted himself to the threefold task of being a composer, professor, and researcher. In 1973, after the collapse of Salvador Allende’s government, Becerra sought political asylum in the Federal Republic of Germany (what was then West Germany), where he has lived ever since.

His work is exceptionally intense and varied, including his cello compositions: three partitas for solo cello, five sonatas for cello and piano, and a concerto for cello and orchestra, dedicated to the excellent Chilean cellist Arturo Valenzuela.

Becerra-Schmidt did me the honor of dedicating his Sonata no. 5 (1997) to me; Edison Quintana and I played it in Chile in 1998 and Mexico in 1999, and recorded it soon after.

Eduardo Cáceres (b. 1955) has had a brilliant career in Chile as a composer, professor, and tireless promoter of contemporary music, both in his own country and abroad. In 1996 he composed Entrelunas for cello and piano.

COLOMBIA Guillermo Uribe Holguín (1880–1971) was the first director of the National Conservatory in Bogotá, founded in 1909, and the most important composer of his generation. Since he studied with Vincent d’Indy at the Schola Cantorum in Paris, there is a marked French influence in all his work, especially in the pieces written prior to 1930, when his nationalistic phase began. Uribe Holguín composed two sonatas for cello and piano.

Blas Emilio Atehortúa (b. 1933) studied in his own country and later in Buenos Aires with Ginastera, Iannis Xenakis, and Luigi Nono, among others. His cello pieces include Romanza (five romantic pieces, op. 85) for cello and piano and a concerto for cello and orchestra, op. 162 (1990). He is currently composing Fantasía concertante for cello and piano, which he hopes to complete by 2005.

Claudia Calderón (b. 1959), a pianist and composer, was born in Palmira, Colombia. She studied music in Cali and Bogotá and later in Hanover, Germany. She has also devoted time to researching the ethnic music of Colombia and Venezuela. In 2000 she composed La revuelta circular, a work for cello and piano, which I played and recorded in 2001.

CUBA In Chapter 5 I discussed my visit to Cuba and my relationship with Cuban music and musicians, so here I will only provide a short list of composers and their works.

Amadeo Roldán (1900–1939) composed Dos canciones populares cubanas for cello and piano.

Aurelio de la Vega (b. 1925), who has lived in Los Angeles since 1959, wrote Leyenda del Ariel criollo (1953) for cello and piano.

Leo Brouwer (b. 1939), born in Havana, is a composer, guitarist, and conductor. He studied guitar with Isaac Nicola, a student of Emilio Pujol’s, and specialized in composition, subsequently complementing his studies at Julliard and at the Hartt College of Music of the University of Hartford (1959–1960). He was the principal conductor of the Cuban National Symphony Orchestra, and since 1992 he has also conducted the Cordoba Symphony in Spain. He has had a brilliant career as a guitarist, composer, and conductor, and is an enthusiastic music promoter, as well. His principal cello work is a sonata for solo cello (1960, revised 1994).

Carlos Fariñas (1934–2002) was born in Cienfuegos and began his musical studies in Santa Clara, Cuba. In 1948 he enrolled in the Havana Conservatory, where he studied with José Ardévol and Harold Gramatges. In 1956 he attended Aaron Copland’s course at Tanglewood, and from 1961 to 1963 he studied at the Moscow Conservatory.

He was director of the music department at the National Theater of Cuba and of the García Caturla Conservatory, a member of Teaching Reform Committee, and head of the Music Department at the National Library. He composed a concerto for cello and orchestra (see Chapter 6) and a sonata for violin and cello (1961).

Guido López Gavilán (b. 1944) has composed Monólogo for cello solo.

ECUADOR In the archives of the Central Bank of Ecuador in Quito, I found two manuscripts of scores composed by the great figure of Ecuadorian music, Luis Humberto Salgado (1903–1977). Entitled Capricho español (1932) and Sonata for cello and piano (1932), they have never been performed. Salgado also composed a cello concerto.

MEXICO In Chapter 6 I referred to my relationship with many Mexican composers and to the works that I have known, played, premiered, and, in some cases, recorded. Here I will present only a brief summary of the principal cello works by Mexican composers.

Ricardo Castro (1864–1907) is the author of the first documented concerto for cello and orchestra by a Mexican composer. Written some time in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, its world premiere took place in Paris in 1902, but the work was soon forgotten. The Mexican premiere was not held until seventy-nine years later, when Jorge Velazco, the Minería Symphony Orchestra, and I performed it in 1981.

Julián Carrillo (1875–1965) was born in a small remote village in the state of San Luis Potosí. He studied composition, conducting, and the violin at Leipzig’s Royal Conservatory, and for three years he played in the famous Gewandhaus Orchestra, conducted by Arthur Nikisch. The Royal Conservatory Orchestra premiered his First Symphony.

On his return to Mexico, he was known as a rather controversial figure, which did not prevent him from becoming the conductor of Mexico’s National Symphony Orchestra and twice director of the National Conservatory.

From the time he was a young man, he had been obsessed with the idea of dividing musical intervals into fractions smaller than semitones. Ever since Bach’s time, the traditional system in western music had been the tempered system, whose scale is divided into twelve equal semitones. After 1924, Carrillo’s compositions were characterized by the division of tones into thirds, fourths, octaves, and sixteenths. Because he had exceeded the limit of twelve semitones, Carrillo christened his system “Sonido 13” (Sound 13). His works require special instruments, like the so-called “metamorphosed” pianos; cellos and other stringed instruments can be used as they are.17

Manuel María Ponce (1882–1948) composed a sonata for cello and piano (1915–1917) while he was in Cuba, and Three Preludes for cello and piano (1932–1933) during a stay in Paris.

María Teresa Prieto (1896–1982), who was my aunt, was born in Spain, but composed practically all of her work in Mexico. For the cello she wrote Adagio and Fugue for cello and orchestra, and a sonata for cello and orchestra. Both works are also available in versions for cello and piano.

Carlos Chávez (1899–1978) was one of the outstanding figures of twentieth-century Mexican music. In 1975 he started working on his concerto for cello and orchestra, but managed to finish only the initial allegro. I premiered this piece in 1987 with the Orchestra of the State of Mexico under its conductor Eduardo Diazmuñoz and under circumstances described in Chapter 5. Chávez also composed Sonatina (1923) and Madrigal (1922), both for cello and piano.

Rodolfo Halffter (1900–1987) divided his time equally between Spain and Mexico, although he wrote most of his work in Mexico. He was also very active as a mentor, teacher, editor, and music promoter. In acknowledgment of his life’s work, he received the National Arts and Letters Award (Mexico, 1976) and the National Music Award (Spain, 1985). Halffter composed his Sonata for cello and piano, op. 26 (1960), commissioned for the Second Inter-American Music Festival in Washington.

Blas Galindo (1910–1993) left an abundance of cello works. Among his most important pieces, I would mention his Sonata for cello and piano (1948) and two that he dedicated to me: the Sonata for solo cello (1981) and his Concerto for cello and orchestra (1984).

As related in Chapter 6, my close friendship with Manuel Enríquez (1926–1994) resulted in four works: Concerto for cello and orchestra (1984), Fantasia for cello and piano (1991), and his own cello transcriptions of Miguel Bernal Jiménez’s Danzas tarascas and Silvestre Revueltas’s Tres piezas, both originally written for violin and piano.

Enríquez composed other excellent cello works: Poem for cello and small string orchestra (1966), Sonatina for solo cello (1962), and Four Pieces for cello and piano. With the exception of Poem, I have recorded all of his works on compact discs.

Joaquín Gutiérrez Heras (b. 1927), a great composer, has written the following works for the cello: Duet for alto flute and cello, Canción en el puerto for cello and piano (1994), Two Pieces for cello and piano, and Fantasia Concertante for cello and orchestra (2005), which I premiered in September 2005.

Manuel de Elías (b. 1939) has composed the Concerto for cello and orchestra that I premiered in Mexico in 1993, as well as other works for solo cello.

Mario Lavista (b. 1943) has written several excellent works for cello: Cuaderno de viaje (1989; two pieces for solo cello), Quotations (1976), and Three Secular Dances (1994), the last two for cello and piano. At the time of this writing, he is composing a work for cello and orchestra, which I hope to premiere in 2007.

I met Federico Ibarra (b. 1946) in 1988, and up to now our friendship has resulted in two very successful pieces that I have commissioned: the Concerto for cello and orchestra (1989), which I have played in many countries and has been widely acclaimed both by the public and critics, and the Sonata for cello and piano (1992), which has met with similar success. He has also composed a sonata for two cellos and piano (2004).

Arturo Márquez (b. 1950) has written a piece for cello and piano (1999) and a concerto for cello and orchestra (1999–2000).

Marcela Rodríguez (b. 1951) has composed a concerto for cello and orchestra (1994), which I premiered in 1997 during the Twenty-fourth International Cervantes Festival, as well as Lumbre (1990), a piece for solo cello.

Eugenio Toussaint (b. 1954) has, to date, composed seven works for cello: Pour les enfants for cello and piano (2000); Concertino for cello and guitar (1993); two cello concertos (1982–1991 and 1999); a piece for solo cello (1992); a tango for cello and piano (1999); and Bachriations for solo cello (2005).