![]()

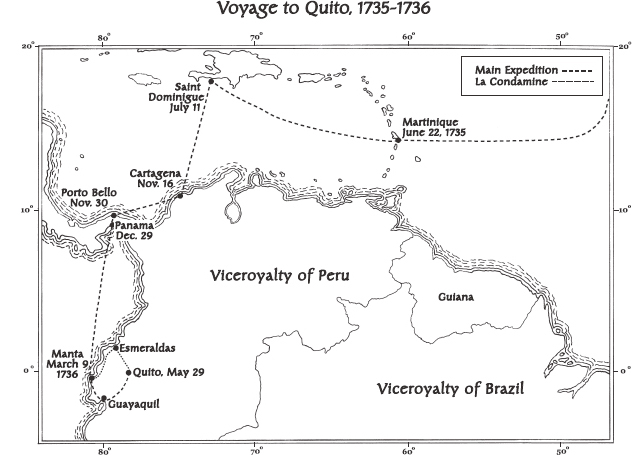

BY EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY STANDARDS, the Portefaix provided La Condamine and the others with pleasant accommodations. Each of the three academy savants had a small private cabin, and while the others had to make do with tiny wooden bunks, they took comfort in knowing that the Portefaix, under the able hand of Captain Ricour, was sailing along at a speedy five knots an hour and would reach the West Indies in little more than a month. They ate a steady diet of salted meats, with La Condamine, Bouguer, and Louis Godin dining at the captain’s table, and each night they all enjoyed a nip of the fine brandy they had brought along. Even the weather was cooperative, the moments when their ship was buffeted about by “large and long waves” interspersed with longer periods of calm.

They also stayed busy with a variety of tasks. From the moment they had put to sea, La Condamine and Bouguer had been compiling navigational logs and conducting experiments, with Jean Godin and the others assisting them. Much of their time was spent studying the utility of several newly invented navigational instruments, which had been awarded prizes by the French Academy of Sciences, including “Mr. Amonton’s sea barometer, and the Marquis of Poleni’s machine to measure the wake of a vessel.” Poleni’s invention was designed to improve on standard methods for calculating a ship’s speed, which involved throwing overboard a weighted wooden disk attached to a rope with knots tied at equal distance along its length. By counting the number of knots that reeled out over a given period of time, sailors could get a rough measure of how fast the ship was moving. The problem was that this method did not account for the speed of the current. Poleni’s machine was supposed to remedy this deficiency, but La Condamine’s experiments were inconclusive on whether it accurately did so.

Another instrument that La Condamine and Bouguer tested was John Hadley’s octant for determining latitude at sea. Mariners had long used the simple astrolabe to determine the altitude of the North Star or the sun, which in turn gave them an estimate of their latitude. Other devices, such as the cross-staff and sea quadrant, were employed for this purpose as well. The shortcoming with such instruments, as Bouguer had detailed in a 1729 paper titled “De la methode d’observer exactement sur mer la hauteur des astres,” was that they were used by sailors standing on a heaving deck, which made it difficult to obtain a precise reading of the angular distance between the horizon and a celestial star. Hadley, a member of the Royal Society of London, had invented a novel solution for this problem. His octant employed two mirrors and a sighting telescope in such a manner that if the instrument vibrated for any reason, the instrument and the objects under observation, such as the horizon and the sun, would move as one. The observed angle between horizon and sun would thus remain the same. His invention, which he had presented to the Royal Society in 1731, was designed to “be of Use, where the Motion of the Objects, or any Circumstance occasioning an Unsteadiness in the common Instruments, renders the Observations difficult or uncertain.” Louis Godin had brought the octant back from his instrument-gathering trip to London, and as the Portefaix sailed across the Atlantic, Bouguer and La Condamine tested its usefulness by measuring the height of the sun each day at noon. With the octant, they found that they could chart the movement of the sun so closely that they could identify the moment, to within fifteen seconds, when it reached its highest point. This, La Condamine noted, was “far beyond the usual limits, which previously did not allow for being certain of midday at sea by closer than two minutes.” Hadley’s invention apparently produced an eightfold improvement in accuracy. Captain Ricour could now be confident that his latitude measurements were accurate to within a couple of miles.

With their minds occupied in this way, the days passed quickly. Even Bouguer found that putting Hadley’s octant to the test and the other experiments had helped him forget his natural “repugnance” for sea travel. The one unsettling moment of the voyage came when Jussieu, the expedition’s botanist, was bitten by a dog that the mission’s doctor, Senièrgues, had brought aboard. Although Jussieu was not badly hurt, Senièrgues decided that the dog needed to be killed. This so upset the sentimental Jussieu that he hid for days below deck in his bunk with the curtain drawn, refusing all entreaties to come out.

They arrived in Martinique in the West Indies late in the afternoon of June 22, 1735, docking at Fort Royal. They had traveled more than 4,000 miles in thirty-seven days, and now they delighted at the sight of the volcano Mount Pelée, its slopes thick with tropical vegetation. This was a gentle introduction to the New World, for Martinique could provide many of the amenities of home. Although Columbus had sighted the island in 1493, naming it Martinica in honor of Saint Martin, the Spanish had never settled it, leaving the door open for a French trading company to claim it in 1635. The French brought in slaves to work sugar plantations and rapidly pushed the native Carib Indians into the far corners of the island. As part of a 1660 treaty, the Caribs agreed to reside only on the Atlantic side, but that peace was short-lived, and soon the Caribs who were not killed in battle fled the island altogether.

La Condamine and the others stayed ten days on Martinique, buying supplies and lugging their barometer up the slopes of Mount Pelée to an altitude of “700 toises above sea level,” where they found the cold, even in the tropics, “severe.”* They were intent on using the barometer to measure altitude in the Andes, and in order to do so, they needed to improve their understanding of how the instrument could be used for this purpose. The barometer had been invented a century earlier by an Italian, Evangelista Torricelli, who had shown that weather-related changes in air pressure caused water in a thirty-five-foot-tall vacuum tube to rise or fall. By replacing water with mercury, which was fourteen times heavier, Torricelli was able to create a barometer less than three feet tall, a size that made his new invention portable. Wealthy people in the late seventeenth century proudly displayed this weather instrument in their homes. However, in 1648, France’s Blaise Pascal observed that air pressure also dropped as one climbed in altitude. Mercury levels in a barometer dropped about one inch for every 1,000 feet gained, but this change in pressure was not precisely linear: The drop in the mercury level grew ever so slightly less pronounced as one climbed higher. What Bouguer hoped to do on this voyage was develop a logarithmic scale that would describe this variable change in air pressure, and Martinique provided an ideal laboratory to launch the effort. He and La Condamine took the barometer to different spots on Mount Pelée and, with the sea visible, they were able to “determine their heights geometrically.” They then correlated their altitude to the barometric readings, a first step toward creating the desired logarithm.

Their next stop was Saint Domingue, a French territory on the island of Hispaniola. They departed from Martinique on July 4, with La Condamine recovering from a mild case of the “illness of Siam,” or yellow fever. One of their guides in Martinique had come down with symptoms of the disease on July 2, and a day later La Condamine began exhibiting them as well. A dreaded sickness in the New World, the illness of Siam’s initial fever and vomiting often gave way to seizures, coma, and death. But Senièrgues and Jussieu treated La Condamine with “all haste,” and he revived so quickly that he later recounted that he was “ill, bled, purged, cured and placed on board within 24 hours.”

Hispaniola had been the first island colonized by Spain, and so it was a sore point with Spain that France had wrested control of its western third in 1697. French pirates had long hidden in the coves and bays on this part of the island, harassing Spanish shipping at every turn, and in 1697, with the decrepit King Charles II slowly dying in Madrid, Spain reluctantly signed the Treaty of Ryswick relinquishing the western region. The Portefaix anchored on July 11 at Fort Saint Louis, on the southern coast, and then sailed around a spit of land to Petit Goave. There the French visitors lodged in a small inn and waited for permission to proceed, a wait that quickly turned frustrating. The governor of the French colony wrote his counterpart in Santo Domingo, asking that he send a ship to take the French academicians to Cartagena, but the Spanish governor wrote back to say that he was unable, at the moment, to provide such transport.* Time was passing, and what unsettled the French academicians, even though they did not want to admit it, was that they knew they were in a race.

Shortly before they had departed from La Rochelle, Maupertuis had proposed to the academy that he lead a second arc-measuring mission, this one to Lapland. By sending expeditions to both Lapland and the equator, Maupertuis had argued, the academy could be assured a more definitive answer about the earth’s shape. Rather than comparing the length of an arc at the equator to that of one in France, the academy would be able to compare arcs measured at the two extremes of the earth, which would greatly lessen the possibility that an imprecise measurement would lead to a misleading result. While this was good science, it was disturbing to those heading to Peru. The group that came back first, they knew, would most likely gain fame for having solved the great question.

As the French and Spanish diplomats exchanged letters, the French scientists occupied themselves as best they could. They determined the longitude and latitude of various forts and towns on the island, and Verguin drew several maps. La Condamine also hired a merchant to make two large tents with awnings, each a copy of the largest tent they had brought with them from La Rochelle. He was tending to a delicate matter, for if they had only one large tent, a question would arise over which of the three academicians would get it. By commissioning two more, he ensured that each would now have his own sleeping quarters. The others in the crew would share three smaller tents, befitting their lower status as assistants.

Even so, as the party lingered in Saint Domingue, tensions surfaced between Godin, Bouguer, and La Condamine. Each had his own ideas about how the expedition should be run, and to make matters worse, Godin, with idle time on his hands, took up with a local woman. Gregarious as always, he delighted in strutting about town with her, which did not endear him to the local populace, and he showered her with gifts. This upset La Condamine and Bouguer, for it meant he was piddling away the expedition’s cash. The three exchanged sharp words on more than one occasion, causing Godin to remind everyone that he was both the senior member of the academy and the expedition’s leader. By early October, even the mild-mannered Jussieu was irritated with Godin, deriding him in a letter home as a “youngbeard without experience.”

Six hundred miles away, two young Spanish military officers in Cartagena—Antonio de Ulloa and Jorge Juan y Santacilia—were similarly growing impatient, wondering if the “French academicians” they were supposed to keep an eye on would ever arrive.

AT FIRST GLANCE, Ulloa and Juan did not appear to be very well suited for the task at hand. They were so young—Ulloa was nineteen and Juan twenty-two—that it seemed certain they would be easily intimidated by the French savants, who were not only older but of much higher status. Yet, as would become evident in the months ahead, King Philip V had chosen wisely. Both Ulloa and Juan were well educated, firm in their resolve, and intellectually curious.

Ulloa, a native of Seville, was the son of a well-known economist, Bernardo de Ulloa. As a child, Antonio was small and sickly, and his father constantly worried that he would never amount to much. When Ulloa turned thirteen, his father decided that the only education that could save his son from mediocrity was harsh experience, and so he asked the commander of Spain’s trans-Atlantic fleet, Manuel Pintado, to take him on as a cabin boy. This was an unusual position for a wellborn boy, and yet no schooling could have offered Ulloa more. The experience both steeled his character and fired his imagination. In 1733, he entered the Spanish naval academy, the Royal Academy of Midshipmen, where he became a member of an elite company, the Guardias Marinas. There he was taught mathematics, astronomy, and navigation.

Juan’s early childhood had also been difficult. Born into a noble family in Valencia, he was orphaned at age three, at which time he went to live with an uncle. He was tutored at home until he was twelve; then he was sent to a boarding school in Malta, where he showed such an aptitude for mathematics that the other students nicknamed him Euclid. At age sixteen, he decided upon a naval career, and like Ulloa, was admitted into the Guardias Marinas. King Philip V promoted them both to the rank of lieutenant for the mission to Peru.

They had reached Cartagena on July 9, 1735, having had the good fortune to travel from Spain in the company of the new viceroy of Peru, José de Mendoza, the Marqués de Villagarcía. Although they were eager for the French to arrive, they had plenty to do. In addition to chaperoning the French visitors, Ulloa and Juan had been asked by Philip V to prepare a thorough report on Peru, and they had taken this responsibility to heart, filling their notebooks with engaging accounts of Cartagena’s history and daily life.

The bay of Cartagena had been discovered by Spaniards in 1502, and its geography made it ideal for a military port. From the sea, ships could reach the city only by sailing through a narrow straight, which in 1735 was guarded by two forts. Even so, pirates and other foreigners had attacked Cartagena numerous times in its 200-year history. Its worst moment had come in 1586, Ulloa and Juan noted, when the Englishman Sir Francis Drake had set the town on fire and extracted a ransom of 120,000 silver ducats from its inhabitants.

As was the Spanish custom, the streets of Cartagena were laid out in a grid, with a plaza mayor in the center, where the administrative buildings, including the Court of the Inquisition, could be found. Well-to-do whites lived in fine houses with wooden balconies, and their homes, Ulloa and Juan observed, were “splendidly furnished.” During the midday heat, the women of these homes could usually be found “sitting in their hammocks and swinging themselves for air,” and everyone, men and women, stopped for a brandy each morning at eleven. Nature and commerce provided a daily feast for their dinner tables. The wealthy of Cartagena dined on rice, grains, fish, meats from animals of every kind—cows, hogs, geese, deer, and rabbits—and a cornucopia of New World fruits, such as pineapples, guavas, papayas, guanabanas, and zapotes. Chocolates filled their cravings for sweets, and nearly everyone, including the women, enjoyed a good smoke.

But these pleasures were reserved for the well-to-do. The other inhabitants of Cartagena, Ulloa and Juan noted, “are indigent, and reduced to mean and hard labour for subsistence.” There was a leper colony in the town, and many of the poor—mostly mestizos and freed Negroes—resided in miserable straw huts, where they lived “little different from beasts, cultivating, in a very small spot, such vegetables as are at hand, and subsisting on the sale of them.” The street markets where such produce was sold had a distinct African tone, the Negro women wearing “only a small piece of cotton stuff about their waist” and caring for their infants in a way that amazed the two Spaniards:

Those who have children sucking at their breast, which is the case of the generality, carry them on their shoulders, in order to have their arms at liberty; and when the infants are hungry, they give them the breast either under the arm or over the shoulders, without taking them from their backs. This will perhaps appear incredible; but their breasts, being left to grow without any pressure on them, often hang down to their very waist, and are not therefore difficult to turn over their shoulders for the convenience of the infant.

As was true throughout Peru, the bringing together of three races—whites, Negroes, and indigenous groups—had produced a multihued population in Cartagena, and the colonial city went to great lengths to identify the amount of “impure blood,” whether black or Indian, that tainted those who were not 100 percent white. The result was a very complicated caste system. When a white mated with a Negro, Ulloa and Juan reported, the child was deemed a mulatto, and it took several generations of marrying back into white families for the mulatto blood to be washed out. The offspring of a mulatto and a white was deemed to be a terceron, and if a terceron married a white, their children were considered quarterones. A mix of quarteron and white produced a quinteron, and the child of a quinteron and a white was considered to have made it all the way back to being a “Spaniard, free from all taint of the Negro race.” When a Negro married an Indian, their offspring were known as sambos, and when a quarteron married a terceron or a mulatto, their children were called salto atras, or “retrogrades, because, instead of advancing towards being whites, they have gone backwards towards the Negro race.” This was a racial ladder of many steps, and everyone knew where he or she stood on it, “so jealous of the order of their tribe or cast that if, through inadvertence, you call them by a degree lower than what they actually are, they are highly offended, never suffering themselves to be deprived of so valuable a gift of fortune.”

Daily life in Cartagena.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (1749).

Ulloa and Juan observed the wildlife of Cartagena with equal diligence. There were tigers, foxes, armadillos, lizards, monkeys, and colorful snakes to be described. At dusk, vampire bats flew in such great numbers that they covered the sky and made their way into homes, where “if they happen to find the foot of any one bare, they insinuate their tooth into a vein, with all the art of the most expert surgeon, sucking the blood till they are satiated.” The two Spaniards identified “four principle kinds” of mosquitoes that tormented the inhabitants of Cartagena, described the life cycle of a parasitic worm called the cobrilla that was about the “size of a coarse sewing thread,” and dwelled at great length upon the nigua, a flea that would pester them for the rest of their days in Peru. This insect liked to bury itself in “the legs, the soles of the feet or toes” and make its nest there, depositing its eggs and eating the host’s flesh for sustenance, all of which caused a “fiery itching.” Removing the insect and its nest often caused extreme pain, because sometimes “they penetrate even to the bone, and the pain, even after the foot is cleared of them, lasts till the flesh has filled up the cavities they had made.” To ward off infection, the wounds were “filled either with tobacco ashes, chewed tobacco, or snuff.”

Cartagena was only the first stop on their journey, but already Ulloa and Juan were proving to be keen observers and able writers, busily compiling notes for the first chapter of a travelogue that would, upon its publication in 1748, become a best-seller throughout Europe.

IT WAS NOT UNTIL early November that the French academicians obtained permission to depart for Cartagena. The governor of Santo Domingo, unable to provide them with a ship, at last allowed them to sail in a French vessel, the Vautour, captained by a Mr. Hericourt. On November 16, the two groups finally met, and while the French were initially a bit resentful of this intrusion into their expedition, the friendliness of the two Spaniards quickly put everyone at ease, La Condamine remarking that “the knowledge and the personal merit of these two officers showed the high level of the guards of the Spanish Navy.” With everyone together now, they debated the best way to proceed. Several in the group favored heading overland to Quito, a journey that would involve poling up the Magdalena River for 400 miles and then proceeding on mules through the Andes for another 500 miles. “Ordinary travelers” took nearly four months to make this trek, and La Condamine was adamantly opposed to this route. Their equipment and delicate instruments would all have to be repacked, and with the large amount of baggage they carried, the journey could be expected to take much longer than usual. All this, he said, would cause “great fatigue, time and expense.” The forceful La Condamine won this argument—indeed, he rarely lost such battles—and on November 24, they all boarded the Vautour for Porto Bello, where they would disembark in order to cross the Isthmus of Panama. Their group numbered twenty-six: Ulloa and Juan had two servants and the French now had twelve, the governor of Saint Domingue having provided them with five or six slaves.

Porto Bello was well known throughout the Spanish Empire as a dreadful place to visit. It was a hub for the Peruvian export trade, the market open forty days each year. All of the goods exported from Quito and points south in Peru came through this port, having been shipped up along the Pacific coast to Panama City and then packed across the isthmus by mule. The mule train would reach Porto Bello at the same time as a convoy of trading ships from Spain, the Galeones, arrived bearing luxury items to be imported into Peru. Tents filled with merchandise crowded the plaza mayor and slaves were sold; with so many traders in town, rent for a single house for the six weeks could fetch “four, five, six thousand crowns,” Ulloa and Juan reported. But the swampy port was also a hotbed of disease. Low mountains surrounded the town, blocking winds that might have refreshed the air or blown away the mosquitoes, and rain pounded down incessantly. The illness of Siam and “fever,” soon to become identified as malaria, often claimed the lives of half the crew of a visiting ship, earning Porto Bello the nickname “the tomb of Spaniards.”

As the Vautour neared the port on November 29, it encountered a storm that stirred all their misgivings. Gale winds tossed the ship about so fiercely that it was unable to enter the harbor, and the men had to wait until the following day to go ashore. Jussieu arrived with a fever, and several others fell sick during the next several days. Local bureaucrats also took to heart King Philip’s order that their baggage be closely inventoried. “These verifications were so precise,” La Condamine complained, “that we were unable to prevent the customs officials from discovering a metal mirror which formed part of a catoptrical telescope, which we feared the humidity in the air of Porto Bello might damage.” A scorpion’s sting deepened La Condamine’s foul mood. He treated the bite with a poultice of his own making, which, he reported, relieved the pain so well that it could replace “all of the ridiculous and disgusting remedies used in the country.”

The men were stranded in Porto Bello for nearly a month. The route across the isthmus to Panama City had been made impassable by rain—La Condamine called it “the worst road in the world.” Their only alternative was to travel up the Chagres River, and that required waiting for the governor of Panama to send them river-boats. They spent the time doing what experiments and good deeds they could. After Jussieu recovered from his fever, he provided medical care to the local populace; Godin and Bouguer measured the length of the seconds pendulum; and Ulloa, Juan, and Verguin mapped the town. But most days were gray and damp, so gloomy that even the two Spaniards concluded that the town was “cursed by nature.” The incessant croaking of frogs kept them awake all night, and in the morning, if it had rained, the streets would be so blanketed with toads that the men could barely walk “without treading on them.”

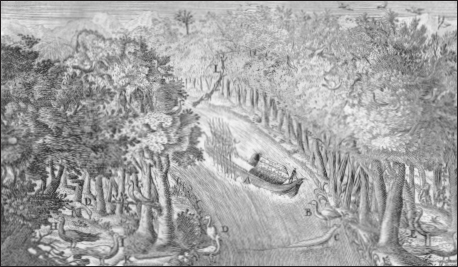

The vessels that arrived for them on December 22 were flat-bottomed barges known as chatas. Each had a cabin at its stern for the comfort of passengers, and a crew of “eighteen to twenty robust Negroes” manning the oars. The forty-three-mile trip up the Chagres turned out to be an unexpected joy. For the first two days, the flow of the river was such that they could proceed by rowing, but then the river’s speed quickened and its depth lessened, so they poled their way along. The surrounding wilderness, Ulloa wrote, was so glorious that “the most fertile imagination of a painter can never equal the magnificence of the rural landscapes here drawn by the pencil of Nature.” Alligators sunned themselves on the riverbank, turtles floated by on drifting tree limbs, and everywhere they looked they could see the colorful plumage of peacocks, turtle-doves, and herons. Monkeys diverse in size and color swung from every tree, and each night, the boat’s crew would gather food from the forest for their supper, plucking pineapples from trees and hunting pheasants and peacocks. Monkey was also served, and this meal, Ulloa confessed, initially made some of the group uneasy:

When dead, [the monkeys] are scalded in order to take off the hair, whence the skin is contracted by the heat, and when thoroughly cleaned, looks perfectly white, and very greatly resembles a child of about two or three years of age, when crying. This resemblance is shocking to humanity, yet the scarcity of food in many parts of America renders the flesh of these creatures valuable, and not only the Negroes, but the Creoles and Europeans themselves, make no scruple of eating it.

As they ascended the Chagres, La Condamine mapped its winding route, and Jussieu, at every possible occasion, urged them to stop so that he could gather plant specimens. It took them five days to reach Cruces, a small village at the head of the river, and from there it was a short fifteen miles by mule to Panama City, where they arrived late in the afternoon on December 29. Here they spent the next seven weeks making arrangements for a boat to take them south to Peru, and except for the fact that La Condamine, Bouguer, and Godin continued to quarrel over money and plans for measuring the arc, the respite was welcome. All of the French members of the expedition studied Spanish, and the three academics performed various investigations “of the thermometer, the barometer, and variations of the magnetic needle,” La Condamine reported. Jussieu explored the local vegetation, going out alone on walks each day with a bag on his back to gather botanical specimens. “I see that this trip,” he wrote in a letter to his brothers on February 15, 1736, “which shall after all have but one (stated) purpose, will in fact collect knowledge of geographic, historical, mathematical, astronomical, botanical, medicinal, surgical and anatomical subjects, etc. As we go along we collect instructive reports, which shall make up a comprehensive and fascinating body of work.”

Along the Chagres River.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (1749).

Meanwhile, Jean Godin, Couplet, Verguin, and the other assistants, when not helping the academics with their studies, enjoyed being tourists. They sampled oysters and other regional delicacies, like iguana seasoned with red pepper and lime juice, a recipe that unfortunately failed to hide the “nauseous smell” of the reptile’s white meat. Several times they stood along the shore and watched Negro slaves dive for pearls in the bay. Ten or twenty of them would go out in a boat at a time, and with a rope tied around their waists, they would jump overboard with small weights to accelerate their sinking. They dove to depths approaching fifty feet, Ulloa discovered, and in order to make the most of each descent, the divers would put an oyster under the left arm, one in each hand, “and sometimes another in their mouth,” before rising to breathe. They went down time and again until their daily quota was filled, and all the while they had to be on the alert for sharks, octopuses, and huge stingrays that haunted the bay. The boat’s officer also kept an eye out for these marauders and would tug on the ropes at the first sight of one, but this scheme, Ulloa lamented, was often “ineffectual” in protecting the divers. More than one slave had lost an arm or a leg or his life to a shark, and several—or so Ulloa was told—had been killed by giant rays, a “fish,” it was said, that “wraps its fins round a man, or any other animal, that happens to come within its reach, and immediately squeezes it to death.”

They sailed from Panama City on February 22, having chartered the San Cristóbal for the 800-mile voyage down the coast. They were eager to be in Peru, and yet their plans for precisely how they would proceed when they arrived were still quite unsettled. The ongoing feud between the three academicians was now focused on whether they should attempt to do their arc measurements along the coast, which Bouguer and La Condamine favored, or in the Andes, as Godin desired. The San Cristóbal crossed the equator on March 8, and a day later, it dropped anchor in the bay of Manta. The expedition members should have been overjoyed—the snow-capped Andes were now visible in the distance—but the tension between the three leaders was so palpable that Senièrgues, in a letter to Bernard and Antoine de Jussieu, worried that the expedition was blowing apart:

Tomorrow we are to see if the terrain will be adequate for the measurement of a base. Mr. Godin does not agree and intends to leave for Guayaquil and from there go directly to Quito. Mr. de La Condamine already announced in front of everyone that if no one wanted to stay he would remain alone. If he feels this strongly about it, Mr. Bouguer will no doubt remain with him. Mr. Godin has not been speaking to them for some time now. They fight like cats and dogs and attack each other’s observations. It is not possible that they will remain together for the rest of this trip.

To investigate the coast, they traveled to Monte Christi, a small village about eight miles inland. They were put up by the locals in bamboo huts raised on stilts, La Condamine awaking that first night to the unsettling sight of a snake dangling overhead. After the expedition surveyed the surrounding terrain, Bouguer, on March 12, wrote a formal memorandum to Godin. If they were to do their survey work here, he argued, it would save them the time and expense of transporting their gear from Guayaquil to Quito, which would require hiring more than 100 mules. It would also be “easier to provide for the subsistence of our company” along the coast, he wrote. Nor should it matter that King Philip was expecting them to do their work around Quito. Spain would be well served by their staying here: “I can even dare to add that it is within [the king’s] interest that our operations be carried out in the indicated place … because, in fact, we cannot conclude our work near the sea without drawing up a map which Navigators shall find invaluable.”

Although there might have been much to recommend Bouguer’s proposal, Godin did not want to discuss it. He was the leader of this expedition, Spain was expecting them to do their work around Quito, and that was that. Besides, Ulloa and Juan had explored the terrain, and they did not see the same opportunity that Bouguer did. The landscape around Manta, they wrote, was “extremely mountainous and almost covered with prodigious trees,” which made “any geometrical operations … impractical there.”

The leaders of the group were at loggerheads, and yet at the last moment, they resolved the matter in a way that at least held open the possibility of a later reconciliation. On March 13, everyone but La Condamine and Bouguer—and their personal servants—boarded the San Cristóbal, which was newly supplied with food and water. They would continue along the coast to Guayaquil and then travel inland north to Quito. La Condamine and Bouguer, having lost this particular battle, would conduct some experiments along the coast and then make their way to Quito. The bitterness of the moment, they all hoped, could be forgotten once they had some time apart, and not even Ulloa and Juan stopped to think about what else La Condamine and Bouguer might be accomplishing by staying behind. The two French academicians had barely stepped into Peru, and yet, once the San Cristóbal set sail, they had already freed themselves from their Spanish minders, a precedent for traveling about the colony with independence.

In anticipation of a lunar eclipse on March 26, La Condamine and Bouguer quickly built a makeshift observatory on the outskirts of Monte Christi. The event would provide them with a celestial timepiece, one much easier to use than Jupiter’s satellites, enabling them to fix the longitude “of all this coast, the most westerly of South America.” Skies were clear that night and both were elated to have made such “an extremely important observation,” Bouguer wrote. They now knew that Monte Christi was fourteen leagues west of the meridian at Panama City, and that the nearby Cape of Saint Lorenzo was four leagues further west. When these data reached France, they enabled cartographers to draw the South American continent with much greater accuracy than ever before.

Over the next few weeks, La Condamine and Bouguer made their way north along the coast, traveling by horse along the beach. They stopped in several villages—Puerto Viejo, Charapoto, and Canow—and learned about the local folklore. Centuries ago, they were told, the people living in this region had worshipped “an emerald the size of an ostrich egg,” which was kept in a temple. When the Spanish arrived, the natives had hidden the precious stone, and they had remained mum about it ever since. Their silence, Bouguer observed, was wise, for if the Spanish had ever been able to find the source of the emeralds, the Indians would have immediately been put to work digging for more, a toil “of labour painful to excess, which they alone would bear the weight, and with but little portion of the profits.”

In early April, La Condamine and Bouguer set up camp along the Rio Jama, just a few miles south of the equator. Here Bouguer spent several weeks studying the refractory properties of the atmosphere, which he had been investigating ever since reaching Petit Goave. He planned to make similar studies once he reached Quito, enabling him to answer a critical question: Was refraction—which altered the apparent position of stars—more or less pronounced at higher altitudes? This difference would have to be factored into their arc-measuring calculations. The bitter feelings of Manta had definitely subsided, and on April 23, Bouguer decided that it was time to turn back. He had finished his refraction studies, and the rigors of traveling along the coast had worn him out. He found the heat oppressive, the insects a “plague,” and he had even grown tired of the birds in the forest, which, to his ear, produced a “discordant stunning noise.” He would hurry on to Guayaquil and try to catch Godin and the others.

La Condamine, however, was eager to continue north. While Bouguer had been at his Rio Jama camp, La Condamine had spent five days fixing the point where the equator crossed the coast. This was at “Palmar, where I carved on the most prominent boulder an inscription for the benefit of Sailors,” he wrote in his journal. “I should have perhaps included a warning to not stop at that place; the persecution one undergoes night and day from mosquitoes and the different species of flies unknown in Europe is beyond any exaggeration.” He was happy to be on his own, with only a servant by his side, and it mattered little to him that at every step of the way, he had to fight legions of mosquitoes and drag along a bulky quadrant and telescope. These were inconveniences that any adventurer could expect.

![]()

AFTER ARRIVING in Guayaquil on March 26, Godin and the others were unable to depart at once for Quito, the constant rains making travel overland impossible. So much rain fell in April that the river overflowed its banks, driving “snakes, poisonous vipers and scorpions” into the houses where they were staying, Ulloa and Juan complained. The streets turned so muddy that people had to walk from the porch of one house to the next over planks set down as bridges between them. Waterlogged rats scurried about everywhere, marching through ceiling rafters at night with such a loud step that it was difficult to sleep.

On May 3, they thankfully escaped from Guayaquil aboard a chata, heading up the Guayaquil River to Caracol, a distance of about eighty miles. Indians living along this stretch of water, Ulloa and Juan noted, skillfully hunted fish with spears and harpoons. In smaller creeks, the Indians would chop up a plant root, called barbasco, mix it with bait, and toss the mixture into the water. The herbal concoction would knock out the fish, which would then float to the surface, enabling the Indians to scoop them up with nets. Alligators, some nearly fifteen feet long, lined the banks, and those that had tasted human flesh before were rumored to be “inflamed with an insatiable desire of repeating the same delicious repast.” But insects were the worst menace:

The tortures we received on the river from the moschitos were beyond imagination. We had provided ourselves with moschito cloths, but to very little purpose. The whole day we were in continual motion to keep them off, but at night our torments were excessive. Our gloves were indeed some defense to our hands, but our faces were entirely exposed, nor were our clothes a sufficient defense for the rest of our bodies, for their stings, penetrating through the cloth, caused a very painful and fiery itching. … At day-break, we could not without concern look upon each other. Our faces were swelled, and our hands covered with painful tumours, which sufficiently indicated the condition of the other parts of our bodies exposed to the attacks of those insects.

La Condamine marks the equator.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur (1751).

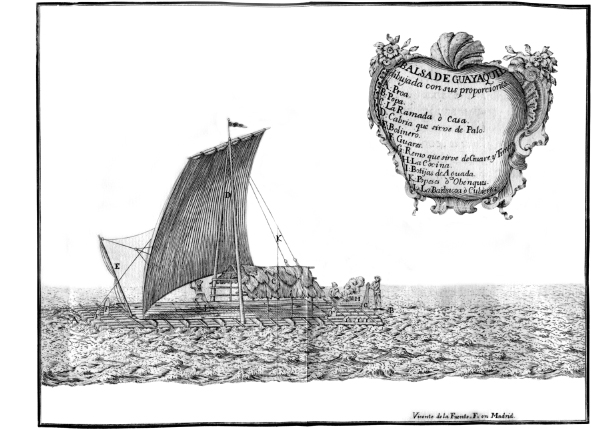

A balsa raft in the Bay of Guayaquil.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (1749).

After eight such miserable days, they transferred their baggage at Caracol to the backs of seventy mules and immediately found themselves mired in a bog. The mules “at every step sunk almost up to their bellies,” and when they finally reached the Ojibar River, only twelve miles from Caracol, they had to spend the night in a village with the unhappy name of Puerto de Moschitos. Jean Godin and a few others, in an effort to find relief from the insects, “stripped themselves and went into the river, keeping only their heads above water, but the face, being the only part exposed, was immediately covered with them, so that those who had recourse to this expedient, were soon forced to deliver up their whole bodies to these tormenting creatures.”

They now began their climb into the mountains, and while they had the pleasure of passing many beautiful waterfalls, some more than 300 feet high, the path was so narrow that as they rode on the mules, they frequently banged “against the trees and rocks,” giving them a collection of bruises to go with their multitude of insect bites. They also had to cross swaying bridges strung high over cascading rivers:

The bridges [are] made with cords, bark of trees, or lianas. These lianas, netted together, form an aerial gallery, which is suspended from two large cables of similar materials, the extremities of which are fastened to branches of trees on opposite banks. Collectively the whole of these singular bridges resembles a fisher’s net, or rather an Indian hammock, extending from one to the other side of the river. As the meshes of this net are very wide, and would suffer the foot to go between them, a sort of flooring is superimposed, consisting of branches and shrubs. It will readily be conceived, that the weight of this network, but especially that of the passenger, must give a considerable curve to the bridge, and when, in addition, one reflects that the traveler passing it is exposed to great oscillations, to which it is incident, particularly when the wind is high, and he reaches near the middle, this kind of bridge, which is oftentimes thirty fathoms long, [it] must needs have something frightful in its aspect. The natives, however, who are far from being naturally intrepid, pass such bridges on the trot, with their loads on their shoulders, together with the saddles of the mules, which cross the river by swimming, and laugh at the timidity of the traveller who hesitates to venture [across].

Huts on the Guayaquil River.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (1749).

Even more frightening, they discovered that their lives were now dependent on their mules’ having good judgment and a steady step. The muddy trail was filled with holes, “near three quarters of a yard deep, in which the mules put their fore and hind feet, so that sometimes they draw their bellies and riders’ legs along the ground. Should the creature happen to put his foot between two of these holes, or not place it right, the rider falls, and, if on the side of the precipice, inevitably perishes.” They spent two or three days in this manner, at times inching along ledges that looked out over “deep abysses,” which, Ulloa and Juan confessed, filled their “minds with terror.” They reached an altitude of more than 10,000 feet, having ascended the western cordillera of the Andes,* and then, in the early afternoon of May 18, they crossed over a mountain pass called Pucara. Now they began their descent into the valley below, the slopes so steep and muddy that the mules slid down on their bellies, with their forelegs stretched out, moving with the “swiftness of a meteor.” All that the startled riders—Ulloa, Juan, Louis Godin, Jussieu, Senièrgues, Hugo, Morainville, Verguin, Couplet, and Jean Godin—could do was hang on for dear life.

They spotted the village of Guaranda just before sunset. A sorry-looking bunch of travelers, the lot of them bruised, muddied, and exhausted, they felt overwhelmed with relief when the corregidor of the town came out to greet them. A priest then appeared, leading a parade of Indians boys waving flags, dancing, and singing, and as the expedition entered the town, bells were rung, “and every house resounded with the noise of trumpets, tabors and pipes.” When they expressed their surprise, they were informed that such a reception was not at all unusual, but was given to all who entered the town. It was Guaranda’s way of “paying congratulations” to those who had survived the perilous journey from Guayaquil.

They now had to travel north for 120 miles to reach Quito. They left Guaranda on May 21, skirted around the flanks of snow-capped Mount Chimborazo, a volcano more than 20,000 feet tall, and spent that first night in a stone cave called Rumi Machai. Over the course of the next week, they stumbled across the ruins of an Inca palace, awoke several mornings in huts covered with ice, crossed several deep chasms formed by earthquakes, and then, on May 29, at dusk, they rode into Quito. There they were greeted with every civility by the president of the Quito Audiencia,† Dionesio de Alsedo y Herrera, their journey of twelve months having finally come to an end.

![]()

BOUGUER AND LA CONDAMINE fared even worse in their travels. Bouguer, after leaving La Condamine at the Rio Jama, had suffered a miserable journey down the coast to Guayaquil, the trail so swampy that even mounted on a horse, he was often up to his knees in water. He reached Guayaquil three days after the others had departed, and he then followed in their wake all the way to Quito. His travel, however, was slowed by his poor health, and he did not arrive until June 10.

At first, La Condamine’s trip had not been too unpleasant. After he and Bouguer split up, he had traveled north in a sea canoe, hugging the shoreline and stopping to determine the longitude of landmarks along the coast, such as the Cape of San Francisco. He was filling out the map that he and Bouguer had begun in Manta, and he continued his sea travels for more than 120 miles, until he reached Esmeraldas, a town populated primarily by free Negroes, the descendants of slaves who had escaped from a nearby shipwreck fifty years earlier. There he had the good fortune to meet the governor of the province, Pedro Maldonado, who had heard from administrators in Quito about the French mission. Maldonado was about the same age as La Condamine, and he shared his enthusiasm for exploration and science. A lasting friendship was born, and Maldonado told La Condamine of his plans to build a road from Esmeraldas to Quito—a route, he said, that La Condamine could now take.

The first leg of this 140-mile trip was up the Esmeraldas River. The river was so named because the conquistadors had come upon natives mining gems from its banks, and La Condamine, ever the indefatigable scientist, mapped its every turn. After that, he plunged into the jungle. Maldonado’s vision for a road to Quito was just that—a dream for the future—and La Condamine had to bushwhack his way through the forest. His Indian guides cut their way through the brush with axes, La Condamine carrying his compass and thermometer in his hands, “more often than not on foot rather than horseback.” It rained every afternoon, La Condamine dragging “along several instruments and a large quadrant, which two Indians had a hard time carrying.” The dense foliage slowed their progress, and yet La Condamine turned even this to his advantage, collecting “in this vast jungle a large number of singular plants and seeds,” which he looked forward to giving to Jussieu upon his arrival in Quito. His mood turned sour only after he was abandoned by his guides. He had but one horse to help him carry his goods, which consisted of a hammock, a suitcase of clothes, and his treasured instruments, which he was loathe to leave behind.* He was also nearly out of food: “I remained for eight days in this jungle. Powder and other provisions became scarce. I subsisted on bananas and other native fruits. I suffered a fever which I treated by a diet, which was recommended to me by reason and ordered by necessity.”

He emerged from this solitude by “following the crest of a mountain,” coming upon a narrow path much like the one that Godin and the others had followed into the Andes from Guayaquil. The trail passed waterfalls and crossed ravines “carved by torrents of melting snow,” and La Condamine, like the others, found the liana bridges nerve-racking. Halfway up the Andes, he came upon several Indian villages—Niguas, Tambillo, and Guatea—where the natives, known as Los Colorados, colored themselves with red paint. In the last of these, he obtained new guides and mules. Because he had no money left, he was forced to leave behind his suitcase and quadrant as a guarantee that someone would return and pay for these services. Los Colorados led him to Nono, a village high in the Andes, where a Franciscan monk supplied him with all that he needed for the rest of his journey. La Condamine made his way ever higher into the mountains, stopping at times to catch his breath. The path scooted around the northern flank of boulder-strewn Mount Pichincha, a volcano that topped 15,700 feet. As he reached the highest point on the trail, the clouds lifted, and suddenly he could see for miles:

I was seized by a sense of wonder at the appearance of a large valley of five to six leagues wide, interspersed with streams which joined together to form a river. I saw as far as my sight could see cultivated lands, divided into plains and prairies, green spaces, villages and towns surrounded by bushes and gardens. The city of Quito, far off, was at the end of this beautiful view. I felt as if I had been transported to the most beautiful of provinces in France, and as I descended I felt the imperceptible change in climate by going from extreme cold to the temperature of the most beautiful days in May.

His journey had come to an end. It was June 4, 1736, and now La Condamine and the others could begin the daunting task of measuring a degree of latitude in this rugged terrain.

* Mount Pelée is 4,586 feet tall.

* Although La Condamine is unclear on this point, apparently the Portefaix had not been authorized to sail to a Spanish port.

* The Andes in this part of South America consists of two mountain ranges, or cordilleras, separated by a valley twenty-five to thirty-five miles wide.

† The Viceroyalty of Peru was divided up into a number of administrative districts known as audiencias. The Audiencia de Quito governed a territory about five times the present size of Ecuador, stretching from the Pacific to the Amazon.

* La Condamine writes of being alone once the guides abandoned him. It is most likely, however, that he was still accompanied by a personal servant.