![]()

QUITO IS BUILT ON the lower slopes of Mount Pichincha, a volcano that has often rained ashes down on the homes below. The landscape is also cut by two deep ravines carrying waters tumbling down from Pichincha, which, in the 1700s, was covered with snow and ice. Such topography makes it an unlikely place for a city, and yet, as the members of the French expedition quickly sensed, there was something special, even spiritual, about this spot. Upon his arrival, Bouguer called it a “tropical paradise,” and at every step they were confronted with evidence of its long history. Barefoot Indians trotted through the city, the men dressed in white cotton pants and a black cotton poncho, and they greatly outnumbered those of Spanish blood.

As far back as the fifth century A.D., Indians had come to this spot to trade goods, with gold, silver, and pearls the treasured items of the day. The people in this region came to be known as the Quitus. In the eleventh century, a tribe living along the coast, the Caras, ascended the Esmeraldas River into the valley, intermarrying with the Quitus, and collectively the two groups came to be known as the Shyri Nation. Two centuries later, the Shyris intermarried with the Puruhás to the south, forming the peaceful Kingdom of Quitu. The people worshipped the sun and built an observatory to study the solstices.

Around 1470, the Incas, led by the great warrior Tupac Yupanqui, began their conquest of this kingdom, capturing the city of Quitu in 1492. They brought with them a language, Quechua, which they made the common tongue of the realm, and for the next thirty-five years, during the reign of Huayna Capac, the Inca Empire prospered, with Quito its northern capital. Huayna Capac died in 1525, and after his son Atahualpa was killed by Pizarro at Cajamarca in 1533, one of Pizarro’s men, Sebastián de Benalcázar, marched north to lay claim to Quito. He entered Quito in December 1534, with 150 horsemen and an infantry of eighty, but found it deserted and in ruins. Rumiñahui, a local Indian chieftain who had remained loyal to the Incas, had torched the city rather than hand it over to the Spaniards.

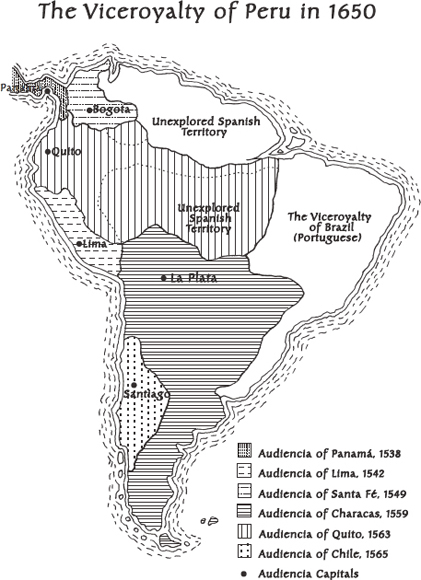

Benalcázar founded the new village of San Francisco de Quito atop the ashes of the old. As was their custom, the Spaniards plotted out a blueprint for their city, locating the plaza mayor close to the old Indian marketplace. In 1563, Spain made Quito the capital of the Audiencia de Quito, a jurisdictional district that stretched more than 1,500 miles north to south and 500 miles east to west. As a capital, Quito was home to all the fixtures of colonial government—an administrative palace, a judicial court, and a royal treasury. By the early eighteenth century, it could also boast of three colleges and a hospital (founded in the sixteenth century), and it was famous throughout Peru for its elaborate cathedrals.

The people of Quito had been waiting for the arrival of the French expedition for months, for Philip V’s letter, in which he urged his representatives to treat the visitors well, had reached them on September 10, 1735 (thirteen months after it was written). No one had been quite sure what to expect—after all, the city had never hosted a group of foreigners before, and these men were said to be the great minds of Europe—so when Godin and the others arrived on May 29, 1736, with their long train of mules bearing a load of strange instruments, the streets were lined with spectators. The audiencia president, Dionesio de Alsedo y Herrera, put them up in the royal palace and greeted them with a written proclamation, grandly announcing that the two nations were uniting for the “transcendental matters of science.” For three days, Alsedo hosted one dinner and ceremony after another for the visitors, with the wealthy and powerful coming from miles to attend. Members of the town council, the judges of the audiencia court, church officials, and wealthy merchants all came to introduce themselves, and everyone, Ulloa and Juan wrote, “seemed to vie with each other in their civilities towards us.”

Bouguer and La Condamine missed this grand welcome. Godin and the others, while waiting for them to arrive, joyfully explored this city of 30,000 and its environs. Quito, they believed, was the “highest situated” city in the world, its inhabitants—Bouguer would later write—“breathing an air more rarefied by one third than other men.” All found the weather a delight, the city warmed by its proximity to the equator but cooled by its altitude, a combination that created a “perpetual spring.” The valley to the south was a sea of green and gold. Cattle grazed on grassy plots while Indians worked the plowed fields, the mild climate allowing one field to be sown while, on the same day, the one next to it was harvested. Orchards dripped with apples, pears, and peaches, and the entire valley was ringed by snow-capped volcanoes. There was Mount Cotopaxi to marvel at, as well as Antisana, Cayambe, and Illiniza, each one taller than the greatest mountain in the Alps. “Nature,” Ulloa and Juan wrote, “has here scattered her blessing with so liberal a hand.”

Quito and its daily life were equally captivating. Stone bridges spanned the deep ravines that transected the city, adobe homes were built on steep streets, and soaring cathedrals seemed to grace every other block. Throughout the day, the peal of church bells could be heard, and inside the great chapels were “vast quantities of wrought plate, rich hangings (tapestries) and costly ornaments,” Ulloa marveled. Markets in the city were filled with an abundance of meats—beef, veal, pork, rabbit, and fowl—and a dazzling array of colorful fruits. There were apricots, watermelons, strawberries, apples, oranges, pineapples, lemons, limes, guavas, and avocados to try, and all the members of the French expedition agreed that the most delicious New World fruit was the chirimoya, its pulp “white and fibrous, but infinitely delicate.”

Map of Quito in 1736.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur (1751).

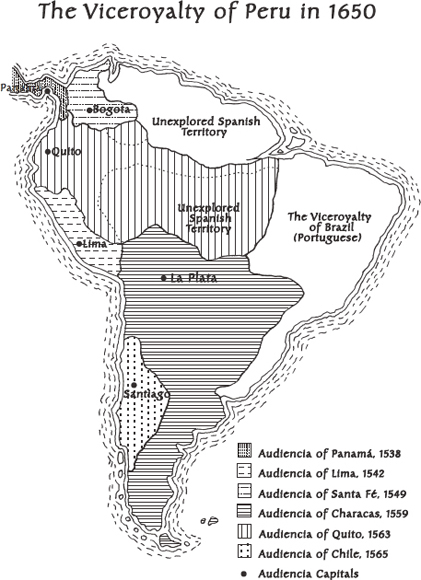

The evening festivities were formal affairs, and the two groups—guests and hosts—did their best to impress one another. The French powdered their wigs and wore their finest silk coats, while the Spanish men of Quito polished their swords, put on their black capes, and in every way possible “affected great magnificence in their dress,” Ulloa wrote. The women of Quito were breathtaking, too, and they did not seem to mind the attention from the visitors. “Their beauty,” Ulloa confessed at the end of one particularly festive evening, “is blended with a graceful carriage and an amiable temper.”

Every part of their dress is, as it were, covered with lace, and those which they wear on days of ceremony are always of the richest stuffs, with a profusion of ornaments. Their hair is generally made up in tresses, which they form into a kind of cross, on the nape of the neck, tying a rich ribbon, called balaca, twice round their heads, and with the ends form a kind of rose at their temples. These roses are elegantly intermixed with diamonds and flowers.

The clothing of different castes in Quito.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (1749), from the 1806 English translation A Voyage to South America.

But perhaps none of the visitors were so smitten as the youngest two members of the French expedition. As Couplet whispered to Jean Godin on more than one occasion, “These women are enchanting.”

WHEN LA CONDAMINE ARRIVED, he did not join his colleagues at the royal palace. Instead, he slipped quietly into town, doing his best to go unnoticed. He was very much the scruffy traveler, bemoaning the fact that he had nothing to wear. He had left the one suitcase he had been carrying in the mountains, and Louis Godin had left his other trunks in Guayaquil, which La Condamine was certain his colleague had done just to spite him. “Seventy mules used to carry cargo as well as persons, and it had not been possible, in my absence, to find a place for a single one of my trunks, nor even for my bed,” he bitterly complained in his journal. La Condamine had no clothes other than the soiled hunting outfit he had been wearing since Manta, attire that left him “incapable of appearing in public in any decent fashion.” He had a letter recommending him to the Jesuits, and he holed up with them in their compound. He remained there, out of sight, for more than a week, working on his maps while a servant fetched the goods he had left behind.

Although La Condamine felt justified in secluding himself, his behavior constituted a major diplomatic gaffe, which Alsedo took as a personal insult. A guest of La Condamine’s rank was expected to enter a city after giving advance notice so that a proper welcome could be provided. Godin and the others had understood this; they had paused a few leagues outside of Quito and sent a messenger ahead, asking the audiencia president for permission to proceed. But not only had La Condamine sneaked into town, unaccompanied by a Spaniard, he then did not even deign to introduce himself. Alsedo found this unimaginably rude, and it stirred up his underlying mistrust of these “foreigners.”

Months earlier, Alsedo had heard whispers that the French were not complying with the terms of their passports. In Cartagena, they had drawn several thousand pesos from the royal Peruvian treasury, which Philip had authorized them to do. However, while Spain had not put any limit on the amount that it would advance the expedition, the French consul in Cadiz, in a last-minute mix-up, had said it would cover these draws only up to 4,000 pesos (about 20,000 French pounds). This was a ridiculously small sum given the expedition’s expenses, and rumors had reached Alsedo that the French, while in Cartagena, had tried to sell contraband valued at 100,000 pesos. The Quito president had immediately written the viceroy of Peru in Lima for advice; the viceroy had cautioned him to carefully “watch that the said astronomers didn’t use the royal permission for purposes that weren’t proper.” Alsedo had been on his guard even before the French had arrived, and now La Condamine had slighted him.

On June 14, La Condamine finally wrote to Alsedo, telling him that he was in town and would like to visit. But the letter did not contain the apology that Alsedo expected, and the audiencia president responded with an icy warning: La Condamine was to comport himself “within the boundaries” set by his passport, he was to refrain from investigating matters that had not been approved by the king, and he should have come to the audiencia palace earlier to explain himself. Why had he separated from his companions in Manta, and why was he now lodged apart from them? Did he realize this violated the terms of his passport? Alsedo also fired off a missive to the viceroy, assuring the Marqués de Villagarcía, “I will always be suspicious of the foreigners, and I have taken precautions that would be considered necessary to protect the security and interests of Spain.”

This ill will did not portend well for the future success of the mission, and yet La Condamine, who seemed to have a particular fondness for diplomatic dustups, responded in a way that could only exacerbate matters. In a few days, he informed Alsedo, he was planning to travel to Nono with Ramon Maldonado, Pedro’s brother, in order to view the June 21 solstice. This village, he noted rather snootily, “would be found near or next to the equator,” where he was supposed to do his work, but if the president did “not like it that I take a walk there with Don Ramon, I will not go.” La Condamine was holding up his passport to trump Alsedo—theirs was a sanctioned trip to the equator, after all—and, pleased that he could call on Philip’s words in this way, he took his trip to Nono. It was, he wrote, “the first time that I had emerged from my retreat.”

When he returned, Alsedo was—as La Condamine subtly put it in his journal—“indisposed” toward him. His Jesuit hosts warned him not to take this dispute any further, particularly since the expedition had other problems to solve. First among them was money. Godin had expected that there would be new letters of credit waiting for them in Quito, but not a single letter from Maurepas or any one else in France had reached the city, even though more than a year had passed since they had departed from La Rochelle. Godin had immediately asked Alsedo for an advance, but the audiencia president had refused—4,000 pesos was all that France had guaranteed. Something needed to be done, and with the rector of the Jesuits, Father Hormaegui, acting as a go-between, La Condamine arranged to see the president.

There was every reason to believe this meeting would go badly. Honor was of such overwhelming importance in colonial Peru that men waged duels over squabbles much more trivial than this one. La Condamine was famously stubborn, unlikely to back down just because it might make things proceed more smoothly. Yet once he arrived at the audiencia palace and bent forward ever so slightly in greeting—about as much deference as La Condamine could muster—the bad feelings began to dissipate. La Condamine explained that it was because of his lack of decent clothes that he had not come to pay his respects right away: How could he call on an honorable representative of the king of Spain in such a state? He had needed to wait until a servant had fetched his suitcase and Bouguer, coming in from Guayaquil, had arrived with his trunk. “I completely satisfied the President on all counts,” La Condamine happily concluded, and indeed, Alsedo was so charmed that he insisted that La Condamine, from that moment forward, become a frequent dinner guest. Alsedo even begged the Jesuits to keep their doors open until 8:30 P.M., past their usual hour of closing, so that he and La Condamine could enjoy an after-dinner brandy together. Theirs was a budding friendship, and La Condamine, at ease now in Quito, opened a shop of sorts in the Jesuit rectory, putting up for sale an array of his personal belongings in order to raise money for the expedition. This was just the type of contraband activity that Alsedo had been worried about, but times had changed, and he quickly became one of La Condamine’s best customers.

The president was not alone in enjoying the new shopping opportunity—many of Quito’s elite found their way to the rectory. Ramon Maldonado bought a number of books, including a history of the French Academy of Sciences, while his wife picked out some diamonds and emeralds. Pedro Maldonado acquired some elegantly embroidered cloth. Alsedo, for his part, purchased fine Holland shirts and cotton clothes. Others bought bedsheets, silk stockings, gloves, switchblades and other knives, needles, gunflints, jewelry, a “prize gun” of La Condamine’s, a diamond-encrusted cross of Saint Lazarus, and various French novelties and trinkets. Tomás Guerrero, a member of the Quito town council, was a regular customer, as was José Benavides, a rich property owner. The flow of goods out of the Jesuit rectory was such that a resale market opened: Alsedo put an assistant, Manuel de Escabo, in charge of buying things and reselling them in Otavalo, while another prominent Spaniard, Antonio Suarez, simply resold the contraband in his shop in Quito.

All in all, La Condamine had turned a difficult situation to his advantage. He had had the good sense to sell his goods at a price that provided the elite in Quito with a fair deal and even offered them the possibility of turning a profit. After a bungled beginning, he had found a way to get along with Quito’s high society, and the expedition was now able to go about its business unfettered by any overly scrupulous supervision, at least as long as Alsedo was president.

ALTHOUGH THE CASSINIS, in their earlier work, had always measured a degree of latitude along a north-south meridian, the French savants were considering measuring both a degree of latitude and one of longitude on this mission. Not only would the east-west measurement enable them to calculate the earth’s circumference along its equatorial axis, but by comparing the two (a degree of latitude versus one of longitude), they might be able to answer the question of the earth’s shape from their “operations alone without needing to refer to anyone else’s,” La Condamine noted. According to Newton’s theory, the diameter of the earth along the equatorial plane was thirty-four miles longer than it was along an axis through the poles, and thus a degree of longitude at the equator should be ever-so-slightly longer than a degree of latitude. If, as the Cassinis believed, the earth was elongated at the poles, then the reverse would be true—a degree of latitude would be slightly longer than a degree of longitude. Taking both measurements was another way of resolving the question of the earth’s shape, and it would complement their initial plan of comparing a degree of latitude at the equator to the one measured by the Cassinis in France or by Maupertuis in Lapland.

Godin, Bouguer, and La Condamine had a basic plan for determining a degree of longitude. After using triangulation to mark off a distance of seventy miles or so along the equator, they could synchronize pendulum clocks stationed at the two ends of this measured line. This synchronization could be done with a luminous signal, such as the flash from a cannon, or, if a mountain obstructed their sight, with a sonic signal, such as the sound of cannon fire. With their clocks in harmony, observers could train their sights on a particular star and mark the time—at each station—that it reached its halfway point in its east-west passage across the sky. The difference in time would tell them how far apart they were in degrees of longitude, and since they would also know the distance between the two stations in miles (or toises), they would have all the information they needed to calculate the circumference of the earth at the equator.

Although this was in theory a relatively straightforward process, Godin, Bouguer, and La Condamine were not of one mind about whether it could be done with sufficient accuracy to produce a useful result. The difference between a degree of longitude and one of latitude at the equator would be very small, less than half a mile. Rather than try to resolve that question now, Godin decided that they should set down a baseline that could be used for triangulation in either a north-south or an east-west direction. In August, Verguin and several of the others scouted around Quito for terrain that might be suitable for this task, and they settled on the plain of Cayambe, thirty-five miles north of the city.

The entire group traveled to Cayambe in early September, and while the academicians debated whether it would do—the land was awfully uneven and was divided by two rivers—Couplet fell gravely ill. He was bled and purged, as was the European custom, and was probably given a dose of local medicine for mal del valle, as fever was called in the Quito area. This Peruvian treatment, Ulloa and Juan noted, was rather painful, “as a pessary, composed of gunpowder, guinea pepper and a lemon peeled, is insinuated into the anus, and changed two or three times a day, till the patient is judged to be out of danger.” Despite such ministrations (or perhaps because of them), Couplet died on September 17, only two days after the fever set in.

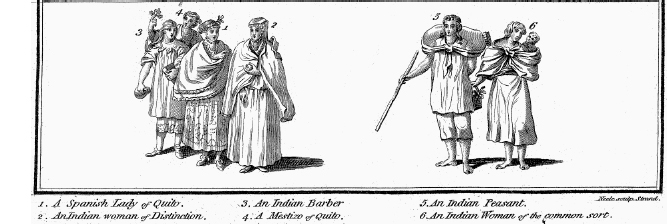

Although the scientists were saddened by this tragedy, they were not at all surprised by it. Everyone had experienced a bout of fever, which could turn deadly at a moment’s notice. Indeed, no sooner had they buried Couplet than Juan fell ill. Someone was always sick, death was an ever-present possibility, and there was nothing for the others to do but go on with their work. Cayambe, they decided, would not serve their purposes well, so they moved their baseline operations to the plain of Yaruqui, twelve miles northeast of Quito. Although the terrain was not as hilly at Yaruqui as at Cayambe, they would need to cross a fifty-foot ravine, which presented a formidable challenge.

It was essential that they determine the length of the baseline to an excruciating degree of accuracy. This measurement would serve as the first side of the first triangle and thus would be “the base of the whole work,” Ulloa observed. From the two ends of the baseline, they would then measure the angles to a third point, and this information would enable them to mathematically calculate the length of the other two sides of the triangle. This process could then be repeated over and over again, with a side of the most recently determined triangle serving as the first side of the next one, so that only the length of the initial baseline actually had to be measured. An imprecise measurement here would corrupt all that followed.

Their proposed baseline ran from Oyambaro to Caraburu, the land dropping 760 feet between these two villages. They marked the terminals of the baseline with large millstones, cleared the brush between these two points, and set up a straight path to follow by carefully aligning intermediate markers every 3,000 feet. As a way of checking their work, they broke into two groups to measure this distance in opposite directions. One group was led by Bouguer, La Condamine, and Ulloa, the other by Godin and Juan, who, after a week of rest, had regained his strength.

Each group employed three twenty-foot-long wooden rods to mark off the distance. They laid the rods, which were color coded to ensure they were always kept in the same order, end to end and moved one rod at a time. By utilizing three rods instead of two (as the Cassinis had done), La Condamine and the others reasoned that there would be less chance that moving a rod to the front would jiggle the others—two stationery rods would be more stable than one. The rods also had thin pieces of copper wire on their ends so that when placed together they would touch at a single contact point, making the measurement more precise. Every possible source of error was considered, the academicians even fretting that changes in temperature or humidity could cause the rods to expand or contract, throwing off their results. Each day they checked the wooden rods with Langlois’s iron toise, which they kept in the shade lest it expand in the hot sun—they needed their ruler to maintain an exact length. Yet another problem was presented by the sloping land. To keep the rods perfectly horizontal, they placed them on sawhorses and used wedges to level them off. When necessary, they utilized a plumb line to move the rods up or down to a new tier, and in this manner they proceeded steplike across the hilly plain.* They used this same method to cross the ravine.

As they performed this delicate operation, they had to contend with weather of the most miserable sort. Although the valley south of Quito might have been a pastoral Eden, the environment north of the city was totally different. Few shrubs or plants grew in the sandy soil, Ulloa and Juan reported, and “violent tempests of thunder, lightning and rain” regularly swept down from the mountains.

Such dreadful whirlwinds form here that the whole interval is filled with columns of sand, carried up by the rapidity and gyrations of violent eddy winds, which sometimes produce fatal consequences. One melancholy instance happened while we were there; an Indian, being caught in the center of one of these blasts, died on the spot. It is not, indeed, at all strange, that the quantity of sand in one of these columns should totally stop all respiration in any living creature who has the misfortune of being involved in it.

With the wind constantly blowing their rods askew, it took the French academicians twenty-six days of dawn-to-dusk labor to measure the baseline. Their results, however, were phenomenal. The two groups’ conclusions varied by only three inches across a distance of nearly eight miles, and so they split the difference: Their baseline was 6272.656 toises long. They returned to Quito on December 5, confident that they had done this all-important first measurement well.

A panoramic view of the plain of Yaruqui.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur (1751).

THROUGHOUT THIS PERIOD, everyone in Quito was keeping up with the progress of the French expedition, even though they were not quite sure what the visitors were up to. Their presence even stirred a passing fancy for things French. Ever since Spain had come under the rule of a Bourbon king, the elite in Quito, influenced by a steady stream of Crown-appointed administrators who came to the town, had come to think of French customs as superior to their own, and now, with the French scientists nearby, the wealthy residents of Quito could more easily imagine being part of that elegant world. The women practiced their curtsies and memorized a few French phrases, and, according to one account of the times, no party was complete unless the host could provide a bottle of French wine.

Pedro Gramesón and his family became personally acquainted with the French mapmakers. The general spoke passable French, having learned it from his father, and his house, one Ecuadorian historian has noted, “was always open for all the French men.” In fact, he could boast that his brother-in-law had played a small role in making the expedition happen. When the French had first proposed it to King Philip V, Spain’s Council of the Indies, which oversaw all colonial matters, had sought advice from several notables in Peru, one of whom was José Augustín Pardo de Figueroa, the Marqués de Valleumbroso. Pardo had a keen interest in science, and he had given his whole-hearted approval. He particularly liked the idea that two Spaniards would be assigned to this expedition, although not because they would keep tabs on the French. Instead, he saw their presence as a way that Spain could participate in this endeavor and learn “the practice of astronomy and trigonometry.” After the academicians had arrived, Pardo and La Condamine had quickly become friends, La Condamine writing in his diary of how impressed he was “by his [Pardo’s] knowledge and how well read he was.” There were other ties as well that brought the Gramesóns closer to the expedition. The Gramesóns and Jean Godin’s family shared mutual close friends, the Pelletiers from Lignieres, a village near Saint Amand. Members of the Pelletier clan living in Cadiz, Spain, shared business interests with the Gramesóns there, while in France the Pelletiers and the Godins had known each other for at least three generations. The connection may have been a distant one, but it made Jean Godin feel welcome at the Gramesóns, and he became a regular guest.

Although Isabel was still in a convent school, she heard all about the French men from her father and through other gossip that filtered into the cloister. The school had not turned out to be such a dismal place. She and the other girls had learned to read and write, and they all enjoyed singing in the choir. Occasionally, the nuns even hosted small fiestas, having musicians and singers in to entertain. And every day, visitors were allowed into the convent parlor to call on the girls, enabling them to keep up with all that went on in Quito. Often they wondered whether it was true, as had been whispered, that the French men had shown the women of Quito a Parisian dance step or two. That was a deliciously scandalous thought, and it naturally caught Isabel’s fancy. She had particular reason to be fascinated by this world—her grandfather, after all, was French, and her family personally knew the scientists—and this interest was starting to blossom into an unusual ambition for a Peruvian girl. She had yet to turn nine years old, but—as would later become evident—she had already begun to dream of one day seeing France for herself.

* A plumb line points to the center of the earth, and thus the French academicians could move their sawhorses up or down along a vertical axis.