![]()

WITH THE BASELINE MEASURED, the French academicians thought that they could complete their mission within eighteen months. Bouguer was even more optimistic. He believed that they might finish by the end of 1737, and he wrote to his colleagues in Paris that he now had “hope of seeing France once more.” But in January of 1737, the French academicians began to realize that they were being overly optimistic, their efforts certain to be delayed by a lack of money, the upside-down world of colonial politics, and their own internal squabbling.

Although it was now twenty months since they had left La Rochelle, they had yet to receive any letters from France. Nearly everyone had sold personal goods to keep the expedition going—even a telescope had been peddled—but in the absence of any new letter of credit, they were, as a group, once again nearly broke. The Peruvian viceroy, the Marqués de Villagarcía, had denied Louis Godin’s request for an advance beyond the 4,000 pesos already given to the expedition. To further complicate matters, Alsedo was no longer the president of the Quito Audiencia. He had been replaced on December 28, 1736, by Joseph de Araujo y Río, a small-minded man who immediately began harassing the French academicians and the two Spanish officers accompanying them. Without any money or political support in Quito, La Condamine decided to travel to Lima, 1,200 miles distant, in order to make a personal appeal to the viceroy. If that failed, he hoped to cash a personal letter of credit that he had brought with him from a French businessman in Paris.

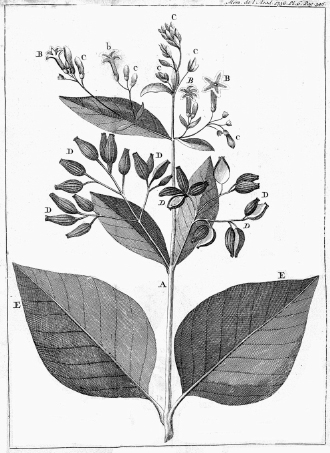

La Condamine left Quito on January 19, 1737, and on his way to Lima, he stopped in Loja to investigate the famous cinchona tree that grew nearby in the tropical rain forest, on the eastern slopes of the Andes. The bark of this tree was in great demand in Europe as a treatment for fever, particularly when the fever was accompanied by terrible sweats and chills (an illness soon to be named malaria.) It was sold there as “Jesuits’ bark” or as “the countess’s powder,” the latter name arising from a story that Francisca Henriquez de Ribera, the Condesa de Chinchón, wife of a Peruvian viceroy, had been miraculously cured of a high fever by a preparation from this tree in 1638. Indians in the Loja area referred to it as quina quina (the bark of barks), and on February 3, La Condamine spent a night with a cascarillero, an Indian skilled in stripping the bark from the trees.

The opportunity to learn more about this tree could easily have justified an entire expedition. While a dose of the countess’s powder often worked wonders, the preparations varied widely in their efficacy. The problem was that there were many species of cinchona, and not all had the same therapeutic value. The Indians of Peru used the same name, quina quina, to describe a balsam tree, and its bark, which regularly showed up in European apothecaries, was worthless. Old World merchants and pharmacists were eager to know how to separate the good from the bad, and La Condamine, after his three-day stay in Loja, wrote a scientific treatise, “Sur l’arbre du quinquina,” on the tree, complete with a drawing of its leaves. He noted that the inner bark came in three colors, white, yellow, and red, and the red one, which was more bitter than the others, appeared to be the most potent against fevers. No one had ever published a detailed botanical description of cinchona, and when the treatise was published by the French Academy of Sciences in 1738, it caused a sensation.

La Condamine’s sketch of Cinchona officinalis.

The Wellcome Trust Medical Photographic Library.

La Condamine arrived in Lima on February 28, only to find that it was an inopportune time to be seeking a loan. Funds were scarce in the capital. Nearly all of the gold and silver from the mines had recently been loaded on a frigate for shipment to Spain. Even if the viceroy had been willing to lend the expedition money, there was little in the royal coffers. Three weeks later, La Condamine received more bad news: The new president of the Quito Audiencia, Araujo, had filed criminal contraband charges against him and sought his arrest. Authorities in Lima searched his belongings thoroughly, and while nothing illegal was found in his possession, his motives were now seen as suspect. All of Lima was buzzing over this scandal when Juan unexpectedly showed up in the capital, with an even more salacious tale involving the new president.

The viceroy’s appointment of Araujo had been unusual, for Araujo was a Creole, a native son of Lima. The relationship between Creoles and chapetones, as those born in Spain were called in Peru, was contentious throughout the viceroyalty, and particularly so in Quito, which was known for being thoroughly dominated by the chapetones. The Creoles disliked the chapetones for their superior airs, and they had been quick to make fun of Ulloa and Juan, too, referring to them as the caballeros del punto fijo (knights of the exact)—men who preferred the pencil to the sword, a put-down that nobody could miss. But the disdain was mutual. The chapetones complained that the Creoles were spoiled and lazy, living off the labor of slaves and Indians and devoting all their energies to frivolous affairs. They have “no employment or calling to occupy their thoughts, nor any idea of intellectual entertainment,” Ulloa and Juan observed. Instead, they said, the Creoles spent most of their time drinking, gambling, and going to “balls and entertainments.” Alsedo, during his term as president, had exacerbated the bad feelings between the two groups by excluding Creoles from the local cabildo, and when Araujo had replaced him, the Creoles had danced with joy, eager to see the tables turned.

Araujo did not disappoint them. Even though he himself had arrived with a mule train of goods to sell in Quito, which was forbidden, he immediately launched an investigation into La Condamine’s contraband activities, confident that it would embarrass Alsedo.* He also found a way to needle Ulloa and Juan, repeatedly addressing them with usted, the common form for “you,” instead of the more formal usía. Given the diplomatic protocol of the day, this was the rankest kind of insult. Ulloa and Juan were members of the Guardias Marinas, in Peru as representatives of the king, and, just as Araujo had hoped, they were outraged. A Creole was acting as their superior, and doing so in public for all of Quito to hear? When Araujo ignored several admonishments to stop, Ulloa reached his breaking point. He charged into the president’s house one morning, brushed aside servants who tried to stop him, and confronted Araujo in his bedroom. Usted? He told off the president with a few choice words of his own, then turned on his heel and left, returning home—as a biographer later wrote—a much “happier man.”

Naturally, Araujo escalated the battle. He sent out armed officers to arrest Ulloa and Juan. The two Spaniards, however, refused to be taken into custody and instead drew their swords, badly wounding one of Araujo’s men before fleeing to the Jesuit church where La Condamine had holed up the previous summer. Enraged, Araujo ordered his men to surround the church. He swore he would starve them out, by God, and he promised bystanders that if the two cowards dared to show their faces, he would have them killed. All of Quito found this a spectacle not to be missed, but the show ended a few nights later when Juan slipped out under the cover of darkness and hurried to Lima to seek relief from the viceroy, whom he had befriended on his trip across the Atlantic.

Once La Condamine and Juan were together, they were able to get the expedition back on track. The viceroy wrote them letters of support and assured them that they could safely return to Quito—Araujo would be counseled to that end. La Condamine, meanwhile, used his personal letter of credit to obtain a loan of 12,000 pesos from a British merchant, Thomas Blechynden, who, by a stroke of good fortune for the French, had come to Lima to collect on a debt owed his trading company. La Condamine also obtained a letter from the viceroyalty authorizing the expedition to draw 4,000 pesos from the royal treasury in Quito, and on June 20, he and Juan returned there, ready to get on with the work of triangulation.

WHILE THESE FEUDS were playing out, the other members of the expedition had been surveying possible triangulation routes. Louis Godin, who wanted to measure a degree of longitude, had headed west from Quito, while Bouguer scouted out the region to the north, and Verguin and Jean Godin reconnoitered the terrain to the south. Once La Condamine returned, they all agreed that they would head south to measure three degrees of latitude first and worry about measuring one of longitude later.

The triangulation would enable them to measure a distance of 200 miles or so along a north-south line. They would run their triangles—a long-distance tape measure, so to speak—down the Andean valley that had been the old Inca highway. The valley was twenty-five to thirty-five miles broad and lined on both sides by mountains that rose to over 12,000 feet, including a number of individual volcanoes that soared above 16,000 feet. By setting up their triangulation points on the top of peaks or on the sides of the higher volcanoes, they figured that they would have clear lines of sight from one point to the next, making it easy to measure the interior angles of each triangle. Partly because of the tensions between the academicians, they decided to break into two groups and divide the work. La Condamine, Bouguer, and Ulloa would form one party, Louis Godin and Juan the other. The assistants would help both groups.

On August 14, La Condamine’s group set out for the first triangulation point, the summit of snow-covered Mount Pichincha. From there, they expected to be able to clearly see the two ends of their baseline in Yaruqui.* However, Pichincha is roughly 15,500 feet high, nearly equal to the tallest peak in the Alps, Mont Blanc, which at that time had never been climbed. During their ascent, first by horseback and then on foot, several members of the group suffered fits of vomiting, and all were “considerably incommoded by the rarefaction of the air,” Bouguer reported. Ulloa fared the worst, fainting and falling face first into the snow. “I remained a long time without sense or motion, and, as I was told, with all the appearance of death in my face.” After Ulloa spent a night in a cave, several Indians helped him reach the summit, where the others were huddled up inside a small hut.

The top of the peak was too small to accommodate the large tents they had had made in Saint Domingue. Instead, their “lodging,” as La Condamine referred to the hut in his journal, was about six feet high, made from reeds lashed to posts that served as a frame. Five or six people crowded into it at a time, Verguin and Jean Godin joining La Condamine, Bouguer, and Ulloa in this humble abode. Their Negro slaves were close by in a “little tent,” the two groups camped out on a summit that dropped off steeply on all sides.*

Along with a quadrant for measuring angles, they had brought a thermometer, a barometer, and a pendulum clock to the summit, and during the first few days, they exulted at the opportunity to do science at such an altitude. They charted temperatures that plunged below freezing each morning, hung the pendulum clock from the posts to measure the earth’s gravitational pull at this great height, and marveled at how low the mercury in their barometer dipped. “No one before us, that I know of, had seen the mercury go below sixteen inches,” La Condamine wrote in his journal. “That is twelve inches lower than at sea level, indicating that the air we were breathing was diluted by almost half of what it is in France, when the barometer goes up to 29 inches.” He calculated that the peak was a “large league” in height (roughly three miles) and that it would take 29,160 steps to climb it from sea level.

At times, they put aside their scientific duties to play around like little kids, “rolling large fragments of rock down the precipice” to amuse themselves, Ulloa wrote. They were living on top of the world, so high that often they could look down on storms roiling the valley below:

When the fog cleared up, the clouds, by their gravity, moved nearer to the surface of the earth, and on all sides surrounded the mountain to a vast distance, representing the sea, with our rock like an island in the center of it. When this happened, we heard the horrid noises of the tempests, which then discharged themselves on Quito and the neighboring country. We saw the lightnings issue from the clouds, and heard the thunder roll far beneath us, and whilst the lower parts were involved in tempests of thunder and rain, we enjoyed a delightful serenity, the wind was abated, the sky clear, and the enlivening rays of the sun moderated the severity of the cold.

But for the most part they suffered, and horribly so. They were pounded regularly by snow and hail, the wind so violent that they feared being blown from the summit should they dare step outside the hut. They spent whole days inside, each trying to warm his hands over a “chafing dish of coals.” They ate a “little rice boiled with some flesh or fowl,” Ulloa noted, and had to boil snow for water. Even a swig of brandy in the evenings did not do anything to chase away the cold, and they soon gave up even this comfort.

The nights were long on the mountain. Each afternoon, at five or so, an Indian servant would fasten the door shut with a leather thong and then hurriedly descend to a cave lower down, where the Indians kept a perpetual fire. The academicians and their assistants would now be shut in for the next sixteen or seventeen hours, their imaginations haunted by the noise of howling winds, the “terrible rolling of thunder,” and crashing rocks. Most mornings, the hut was covered with a “thick blanket of snow,” La Condamine wrote, with such a wall of ice forming against the door that they could not push it open. The Indians usually arrived at nine or ten to dig them out, but one morning—their fourth or fifth on the mountain—no one came. They hollered for help, but the winds were so fierce that their Negro slaves either did not hear them or were in such pain, with swollen feet and hands, “that they would rather have suffered themselves to have been killed than move,” Ulloa wrote. At last, a lone Indian arrived at noon to free them. All of the other Indians had fled, unwilling to endure such hardship any longer, even though they were being paid several times the going rate for their labor.

Despite this harsh environment, the French academicians hoped to measure angles to distant points with an amazing accuracy. Their quadrant, two feet in diameter, was built with reinforced iron to make it steadier, and Langlois had calibrated the instrument so that a degree could be divided into minutes (1/60 of a degree) and seconds (1/3,600 of a degree). The French academicians hoped to make measurements accurate to ten seconds, readings that they could verify by determining if the three angles added up to 180 degrees, plus or minus thirty seconds. Without this precision in the angular measurements, their subsequent calculations of the lengths of the sides of the triangle would not be sufficiently exact. But Mother Nature was not cooperating. There were few moments when it was calm enough to set up the quadrant, and during those brief interludes, Bouguer reported, “we were continually in the clouds, which absolutely veiled from our sight every thing but the point of the rock upon which we were stationed.” Only once or twice were they able to glimpse through their binoculars the markers they had erected at the ends of the Yaruqui baseline. They spent one week on the summit, then a second and a third, and all the while their health deteriorated. “Our feet were swelled and so tender,” Ulloa wrote, “that walking was attended with extreme pain. Our hands were covered with chilblains; our lips swelled and chapped, so that every motion, in speaking or the like, drew blood. Consequently we were obliged to a strict taciturnity and but little disposed to laugh, an extension of the lips producing fissures, very painful for two or three days together.” Their slaves were in equally bad shape, and several “vomited blood.”

Finally, on September 6, after twenty-three days on “this rock,” they came down from Pichincha, defeated. They set up a camp lower on the mountain, humbled by this encounter with the great Andes. “The mountains in America are in comparison to those found in Europe what church steeples are to ordinary houses,” La Condamine sighed. It took them three months to complete their angular measurements from lower down on the mountain, and this, as they all knew, was simply the first of several dozen field stations they would have to inhabit. The year 1737 had nearly come to an end. By this time, Bouguer had hoped they would be ready to return to civilized France, and yet their “severe life,” as Ulloa dubbed it, had only just begun.

WITH THE FIRST SET of triangles completed, Jean Godin’s role became more defined. After Couplet’s death, he had become the youngest member of the expedition, expected to run errands for the three academicians and otherwise be at their beck and call. Most of the other assistants had specific tasks to do or were not even expected to stay with the academicians. Jussieu was off collecting plants, Senièrgues was tending to patients in Quito, and Hugo’s primary role was caring for the instruments, repairing them or even constructing new ones as the need arose. Morainville at times traveled with Jussieu, drawing the plants he collected. That left only Verguin and Jean Godin to regularly assist the three academicians, and Godin was being sent to and fro with such frequency that, as he would later write, he was becoming a “veteran” at moving around the Peruvian landscape. Now that they had come down from Pichincha, Jean was assigned the duty of signal carrier. His job was to head out in advance of the others to set up markers at the triangulation points they had mapped out earlier. One or the other of the two parties, La Condamine’s or Louis Godin’s, would then catch up, setting up a new observation post where Jean had placed the marker. He might stay a short while with them, running errands as they did their critical observations, and then he would scurry on ahead, traveling alone or perhaps with a single servant. He crisscrossed the Andean valley numerous times as he performed this task, bouncing back and forth between the two cordilleras. As he did so, he suffered all the hardships and difficulties that the academicians recorded in their daily journals, although he was often without the solace of companionship. A French historian later wrote what it was like for Jean:

He was always in movement along a meridian line of around 300 kilometers, climbing massive mountains crossed by torrents, walking along the sharp edge of precipices, or through ravines along the banks of the rivers. In these areas in a primitive state, where every step represented a victory of valor and of physical strength, he acquired strength of will and familiarized himself with the country and with the Indians.

This was the sort of life that fostered independence and self-reliance, and a touch of bitterness, too. La Condamine, Bouguer, and his cousin Louis may also have been suffering hardships, but they were almost certain to be hailed for their achievements upon their return to France. But how would he leave his mark? He had left Saint Amand thinking that perhaps he would study the language of the indigenous people in Peru, which had been Quechua throughout the Andes since the time of the Incas. And now, out and about as he was, running errands and carrying signals to distant posts, he often spoke with the local Indians. He began to pick up the Quechua vocabulary, and his ambitions turned more concrete: He would one day produce a grammar of the Incan language, which he would present to the French Academy of Sciences or even to the king of France.

And so his life went: Young Jean spent many of his days and nights in isolated camps, and there, alone and confronting the most frigid conditions, his tent battered by snow and hail, he would scribble the new words of Quechua he had learned into his notebook, struggling to understand how the Indians put these words together into sentences to describe the rugged land they inhabited.

AS THE EXPEDITION headed south from Quito, starting in early 1738, the two groups—La Condamine’s and Louis Godin’s—worked increasingly apart. The tensions between the three academicians remained, and rather than simply dividing the labor of triangulation, each group began producing its own measurement of a meridian line stretching south across the Andes. But this separation, Bouguer reasoned in a letter to the academy in Paris, was not such a bad thing, for the duplication would make for the “strongest and most convincing proof possible.” The two groups were still collaborating in some ways. In the region around Quito, they had plotted off different triangles, but south of the city they “shared” some triangles, each checking the other’s work.

The problems they encountered were numerous, and one that slowed both groups was that they could not keep intact the wooden pyramids they were using as markers. Each pyramid was covered with a light-colored cloth to make it more visible, and to work, the academicians would set up a quadrant atop this pavilion, sighting through the instrument’s telescope similar markers off in the distance. But when the pyramids were not being “carried away by tempests,” Bouguer reported, they were being taken by Indians, who had other uses for the timber and ropes. Jean Godin was not always able to watch over the pyramids until the others arrived, and even when the main party arrived at a camp, the local Indians were apt to creep in at night and grab what they could. After La Condamine and Bouguer rebuilt one of their stations seven times, they grew so frustrated that they decided to start using the smaller tents as markers. “Mr. Godin des Odonais preceded us,” La Condamine wrote, “and had these [tents] placed on the two mountain ranges, at designated points, according to the agreed location of the triangles, leaving an Indian to guard them.” While this procedure worked better than erecting the pyramids, the tents also disappeared more than once, stirring the academicians to lash out in their journals against the Indians, whom they disparaged, in the manner of the times, as slovenly “beasts.”

A field camp in the Andes.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine, Mesure des trois premiers degrés du méridien dans l’hémisphere austral (1751).

With every camp they set up, they had new mishaps and close calls to write about. As they worked on the slopes of towering Mount Cotopaxi, Juan fell into a twenty-five-foot-deep ravine with his mule, luckily escaping with only a few cuts and bruises. Bouguer regularly complained about the nasty conditions, and La Condamine, while riding between two camps, was caught in a fierce storm and had to spend two days in a snow-covered tent without food or water. At last, he used the lens of his glasses to focus the sun’s rays on a pot of snow, which provided a few drops of water that saved him “from this sad situation.”

Despite these hardships, the team members explored their world in every way imaginable. They did not limit themselves to their triangulation work, difficult as it may have been. Through their experiments with a pendulum clock, they discovered—just as Newton had predicted—that the earth’s gravitational pull weakened with altitude. They needed to make the seconds pendulum about one-twenty-fourth of an inch shorter at an altitude of 10,000 feet than it was at sea level, which led La Condamine and Bouguer to calculate that a body that weighed 1,000 pounds at the seashore would weigh one pound less atop Pichincha. They also dragged a barometer to the top of Mount Corazon, a volcano 200 feet higher than Pichincha. Atop the summit, their “clothes, eyebrows and beards covered in icicles,” they figured that no humans had ever “climbed a greater height.” They “were at 2,470 toises [15,794 feet] above sea level,” La Condamine wrote, “and we could guarantee the accuracy of this measurement to four or five toises.”* Their experiments with the barometer were paying off, as Bouguer had come up with a “very simple rule” for using barometric pressure to calculate altitude. Air pressures at higher elevations, he had concluded, “alter in a geometrical progression, while the heights of places are in arithmetical progression.” His method for determining the height of a mountain involved taking a reading at its base and at its summit, and then applying the logarithmic rule he had devised.

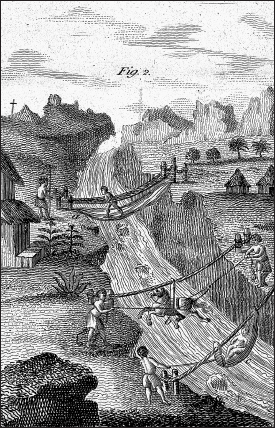

The French scientists were men of the Enlightenment at play. They investigated the climate of the Andes, the expansion of metals in response to variation in temperature, the speed of sound at high altitudes, the rocks and plants, and Inca ruins. Ulloa, meanwhile, was fascinated by some of the clever methods the Indians had devised for navigating this landscape. The road south of Quito regularly crossed ravines several hundred feet deep, and at several of these the Indians had built a “cable car” of sorts, known as a tarabita. Men and animals alike were winched across the ravine, riding in a leather sling attached to the cable, which was a rope made from twisted strands of leather. One such tarabita they came upon was strung at a height of more than 150 feet, the river below charging through a boulder-strewn gully.

As might be expected, all of this activity stirred a great deal of gossip among the locals. The behavior of these visitors was so strange. They climbed to absurd heights on the mountains, peered into odd-looking instruments, and furiously scribbled away in their notebooks. Their three-week stay atop Pichincha had earned them the reputation of being “extraordinary men,” La Condamine noted, and there were whispers among some of the Indians that these strangers were superior beings, shamans of a sort. At a camp near Latacunga, a group of four men even got down on their knees to pray to them. Could they use their powers to help them locate a lost mule? When Ulloa told them they had no such knowledge, the Indians refused to believe him. “They retired with all the marks of extreme sorrow that we would not condescend to inform them where they might find the ass, and with a firm persuasion that our refusal proceeded from ill nature, and not from ignorance.” Others, Ulloa added, were convinced that they were prospectors looking for gold. Wasn’t Mount Pichincha rich in minerals? Hadn’t Atahualpa buried his treasure there? And wasn’t that the reason that everyone came to this land, to get rich?

Inca artifacts.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (1749), from the 1806 English translation A Voyage to South America.

Bridges in eighteenth-century Peru.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (1749), from the 1806 English translation A Voyage to South America.

Even those of the best parts and education among them were utterly at a loss what to think. … Some considered us little better than lunatics, others more sagaciously imputed the whole to covetousness, and [said] that we were certainly endeavoring to discover some rich minerals by particular methods of our own invention; others again suspected that we dealt in magic, but all were involved in a labyrinth of confusion with regard to the nature of our design. And the more they reflected on it, the greater was their perplexity, being unable to discover any thing proportionate to the pains and hardship we underwent.

Indeed, as the months passed, the physical hardships began to wear the men down. They moved steadily from one camp to another, their daily lives, Ulloa noted, marked by “continual solitude and coarse provisions.” Their only respite from this difficult life came when they were passing between camps, when they might have time to spend a day in a little town, everyone so starved for the comforts of civilization that “the little cabins of the Indians were to us like spacious palaces, and the conversation of a priest, and two or three of his companions, charmed us like the banquet of Xenophon.” Loneliness was now creeping into their writings, and by mid-October it was clear they needed a respite. Ulloa fell gravely ill and had to be taken to the nearby city of Riobamba. Louis Godin suffered a similar bout of sickness and returned to Quito to recuperate. The expedition was once again short of funds, supplies were low, and Riobamba, a city of 16,000, offered them a civilized place to rest. They had also recently received a cache of letters from France that had delivered an emotional blow and left them wondering how to proceed.

THE DIFFICULTY IN CORRESPONDING with colleagues in France had led La Condamine, at one point, to complain that he had nearly given up on ever hearing from Paris. The first letter the expedition received arrived in late 1737, shortly after they had come down from Pichincha. In it, Maurepas—the minister who had promoted their expedition to the king—had sought to resolve the ongoing dispute between Godin and Bouguer over the merits of measuring a degree of longitude. Each of the academicians had written Paris to argue his case, and the academy, Maurepas wrote, had agreed with Bouguer’s opinion that it would be a “completely imprudent enterprise.” While Godin had not immediately given up on the idea, his own subsequent experiments on the speed of sound, which he had completed in July 1738, supported the academy’s decision. Godin had determined that sound at this altitude traveled between 175 and 178 toises a second, but that imprecision—of three toises per second—was too great to allow them to use a sound, such as the noise of a cannon being fired, to synchronize watches at two spots along a line measured at the equator. The margin of error would be greater than any difference in distance between degrees of longitude and latitude at the equator, Bouguer noted, and thus “one might even come to believe that the earth is flattened or oblong when in fact it may have a completely different shape.”

So that issue had been resolved, but now, as a result of letters they had just received, they had to question the merits of proceeding even with their latitude measurements. Maupertuis, they had learned, had already returned with his results from Lapland.

The Maupertuis expedition had not lacked its own controversies. Maupertuis was a committed Newtonian, as were the other leaders of the expedition, such as Alexis Clairaut. As a result, many in the academy were ready to dismiss their results even before they left, certain that Maupertuis and Clairaut were too biased to do the work fairly. “Do the observers have some predilection for one or the other of these ideas?” asked Johann Bernoulli, the Belgian mathematician who was a supporter of the Cassinis. “Because if they believe that the Earth is flattened at the poles, they will surely find it so flattened. … [T]herefore I shall await steadfastly the results of the American observations.” Despite such skepticism, Maupertuis and six others had gone to Lapland in April 1736 and returned seventeen months later with an answer. They had determined that a degree of latitude in Lapland was 57,437 toises, which was 477 toises longer than a Parisian arc, as measured by the Cassinis in 1718. Thus, Maupertuis told the academy, “it is evident that the earth is considerably flattened at the poles.” Newtonians naturally pounced on this news, Voltaire gleefully praising Maupertuis as the “flattener of the earth and the Cassinis.”

But as Bernoulli had predicted, the Lapland results did not end the dispute. Many of the old guard in the academy were outraged, Jacques Cassini complaining that Maupertuis was trying to destroy in one year the work his family had taken fifty years to create. He and others criticized Maupertuis’s work as sloppy and snidely suggested that the expedition members had all taken mistresses in Lapland, evidence that they were moral degenerates. Maupertuis was so disheartened that he hurried away to Germany, where he became president of the Berlin Academy of Sciences. “The arguments increased,” he wrote bitterly, “and from these disputes there soon arose injustices and enmity.”

Even though sour grapes may have affected Cassini’s criticisms, from a scientific point of view, he did have a point. The Lapland expedition had measured only one degree, and upon close inspection, its results did not match up with Newton’s mathematical equations. “This flatness [of the earth] appears even more considerable than Sir Isaac Newton thought it,” Maupertuis admitted. “I am likewise of the opinion that gravity increases more towards the pole and diminishes more towards the equator than Sir Isaac supposed.” Something was not quite right with their measurement. The controversy was still alive. A famous Scottish mathematician, James Stirling, declared that he would “choose to stay [neutral] till the French arrive from the South, which I hear will be very soon.” Similarly, Clairaut, in the letter he wrote to La Condamine, noted that the dispute remained so violent that the Peruvian findings were vital to confirming their work in Lapland.

Clairaut had meant to encourage La Condamine with such words, but they had the exact opposite effect. Vital to confirming the Lapland work—this was just what the Peruvian team had always feared. They had been away from France three and one-half years, they were still less than halfway done, and they were now in the position of being viewed by history as having come in second, with all the scientific glory going to Maupertuis. Their own experiments with the pendulum had already led them to suspect that Newton was right, that the earth was flattened at the poles and that Cartesian physics would have to be scrapped. Should they continue their triangulation work another year—or longer—simply to bring this debate to a tidier conclusion?

RIOBAMBA, where they had stopped for rest in October 1738, turned out to be just the place for them to mull over this question and to rethink their expedition. Although smaller than Quito, this city, tucked in the shadow of Mount Chimborazo, was one of the most sophisticated cities in all of Peru, perhaps second only to Lima in this regard. Artisans of all kinds—jewelry makers, painters, sculptors, musicians, and carpenters—lived in Riobamba, and a number of Peru’s most prominent families had come here to live, drawn by the pleasant climate and the city’s reputation as a place of culture. This was the birthplace of the Maldonados, and both Pedro and Ramon Maldonado had become so close to the expedition that they had loaned La Condamine and Louis Godin several thousand pesos. The “agreeable reception provided us [in Riobamba],” La Condamine wrote, “helped us forget the hard times we had spent on their mountains.” The arts, he added, “which were barely cultivated in the province of Quito, seemed to flourish here.” There were Jesuits in Riobamba who spoke French, the town council welcomed them with great warmth, and all of the best families competed to entertain the French savants in their homes. The teenage children of the family of Don Joseph Davalos even put on a play and concert for the visitors, and La Condamine was clearly smitten by their eldest daughter: “She possessed every talent. She played the harp, the harpsichord, the guitar, the violin, the flute. … [She had] so many resources to please the world.” La Condamine, so often bashful around women because of his smallpox scars, was close to falling in love, but alas, as he later wrote, “her sole ambition was to become a nun.”

With the comforts of civilization rejuvenating their spirits, the members of the expedition were able to see with a new clarity what they were accomplishing. They were not measuring one degree of latitude but three, and it was hard to imagine that the Lapland group, up and back so quickly, had conducted its triangulation with the same obsessive attention to detail that characterized their work. They also knew that they were accomplishing much more than simply measuring the arc at the equator. The very enterprise was forcing them to deepen their understanding of the physical properties of the world. They had needed to investigate the atmosphere’s refractory properties, Bouguer concluding that “contrary to all received opinion [it] diminished in proportion as we were above the level of the sea.” They had developed a better understanding of how barometric pressure varied with altitude. They had studied the expansion and contraction of metals in response to temperature change in order to understand how their toise might shrink in the cold. They had needed to perform all these investigations because, in one manner or another, these factors would have to be accounted for in their final calculations of the distance of a degree of latitude at the equator. On this expedition, they were advancing the art of doing science, and learning about nature as they did so.

They were aware too that measuring the arc was not the expedition’s only purpose. They were also unveiling a continent. They were investigating its flora and fauna, with Jussieu gathering bags full of seeds and plants to bring back to France. They were making observations on the social mores and customs of colonial Spain. They were newly curious about earthquakes and volcanoes, and a volcano to the southeast of Riobamba, Mount Sangay, was threatening to erupt even as they convalesced in the city. A few months earlier, La Condamine and Bouguer had climbed to a height never before reached by Europeans, and perhaps by no one on earth. Their stay in Riobamba was giving them an opportunity to nurse their tired spirits and heal their bodies, and soon they could appreciate that they had been set loose in a savant’s playground. Even Bouguer, so often grumpy about the rigors of this trip, was ready to change his tune. “Nature,” he wrote, “has here continually in her hands the materials and implements for extraordinary operations.”

IN MID-JANUARY 1739, they returned to the countryside. Their destination was Cuenca, 100 miles distant, and to get there, they had to map their way through a mountain range that intersected the valley and crossed between the two cordilleras, like a rung on a ladder. In this region, known as the Azuays, they no longer enjoyed the clear lines of sight that had made it possible to bounce their way south from Quito, with signal points set up on mountains on each side of the plain. Instead, they had to triangulate their way through terrain filled with “sandy moors, marshes and lakes,” and they had to do so during the rainy season.

As had been the case in the past, Jean Godin and Verguin went ahead to mark the triangulation points, and the others followed close behind. Everyone was battered as they struggled through this wilderness. La Condamine was robbed at one camp, thrown by his horse and injured at another, and rendered tentless by fierce winds at a third. “I spent eight days wandering around the moors and marshes, without finding any shelter other than caverns in the rock,” he wrote. Bouguer suffered a grave fall in these mountains, and he complained that at night his “sleep was continually interrupted by the roarings of the [Sangay] volcano,” a “noise that was so frightful.”

There were a few moments when the weather cleared and they enjoyed amazing vistas. To the north, the great Andean valley stretched out, with Mount Corazon visible 125 miles away. It was “the most beautiful horizon that one can imagine seeing,” La Condamine enthused. And on March 24, they were treated to the spectacle of an eruption on Sangay. “One whole side of the mountain seemed to be on fire, as was the mouth of the volcano itself,” La Condamine wrote. “A river of flaming sulfur and brimstone forged through the snow.”

But such moments were rare. Their work was hampered at every step by fog, rain, and sleet. In the final days of April, they were blasted by hail and snow. The raging winds destroyed three of their tents, their Indian servants deserted them once again, and they were forced to huddle together in a breach in the rocks. Twenty miles away, in the town of Cañar, a priest led a prayer vigil for them, the people of that town fearful that they “had all perished” in the horrible storm. All seemed hopelessly grim, until, a few days later, a messenger arrived at their newly established camp with a letter that offered some comic relief. Their colleagues in France, it seemed, were worried that with the expedition taking place so close to the equator, they might be “suffering too much from the heat.”

A volcano erupts.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (1749), from the 1806 English translation A Voyage to South America.

By mid-May, they had finally punched their way through the Azuays. The worst was now behind them, and with the terrain becoming gentler, they were able to rapidly make their way down to Cuenca. They arrived there in early June, and over the course of the next month, both groups, La Condamine’s and Godin’s, mapped the last of their triangles. La Condamine and Bouguer determined that they had measured off a meridian that was 176,950 toises long (214 miles). Godin and Juan had measured one that was slightly longer.

The final step in the triangulation process involved proofing their work. To do so, each group used a toise and wooden rods to measure the last side of their last triangle. This was known as a second baseline, and the logic of the proof was simple. Since this line was part of a known triangle, its length could be mathematically deduced. Physically measuring this distance would verify the calculated result. If the two were not equal, it would mean that unacceptable error had crept into their triangulation work, and much of it would have to be redone.

Bouguer’s map of the triangulation area in Peru.

By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Each group had its own second baseline to measure. Although they had shared triangles part of the way, they had mapped out separate finishing triangles in the Cuenca region. Neither of the sites they had picked for this work was ideal. Godin and Juan had selected a plain that was bisected by a broad river; La Condamine, Bouguer, and Ulloa had chosen a spot a little further south, known as the plain of Tarqui, where they had to measure across a shallow pond one-half mile across. There they worked for days on end in the waist-deep water, tying the floating rods to stakes and then moving them forward in the same manner as on land.

As the men placed their final rods, they grew noticeably anxious. Two years of effort would be wasted if their results did not match up. They would have to retrace their steps and recheck all of their measured angles to find the source of the error. But both groups were able to breathe a sigh of relief: Their results were stunningly good. Godin and Juan determined that their baseline, as physically measured, was 6,196.3 toises long, which was only three-tenths of a toise—about two feet—less than its length as mathematically calculated. La Condamine and Bouguer achieved similar results. Their numbers for their second baseline—as measured and as mathematically calculated—differed by only two-tenths of a toise. The two groups had marked off meridian lines stretching more than 200 miles, through mountainous terrain and in miserable weather, and their proofs were accurate to within a couple of feet. At last, La Condamine wrote with understandable pride, “our geometric measurements were completely finished.”

All they needed to do now was measure the height of a star from both ends of their measured meridians, and their work in Peru would be done. This would give them the difference in latitude of their meridians’ endpoints, and with this information in hand, they could precisely calculate the length of a degree of latitude at the equator. Although they would need to build observatories, this would take six months at most. Their results put them in a festive mood, and so they retired to Cuenca, where they hoped to enjoy themselves for a few days before their final push. They would—or so they thought—be on their way home soon.

* When Araujo’s investigation revealed that Alsedo had been one of La Condamine’s customers, Alsedo responded by accusing Araujo of selling contraband, a much worse offense. This set off a court battle between the two that dragged on for years. In many ways, the case typified the legal wrangling that strangled colonial Peru in the eighteenth century.

* Their initial triangle would be formed by Pichincha and the two ends of their baseline. Once they determined the interior angles of this triangle, they could—since they already knew the length of the baseline—calculate the lengths of the triangle’s other two sides.

* The peak they were on is known today as Rucu Pichincha (15,413 feet). The volcano’s rim, Guagua Pichincha (15,728 feet), is a mile away. Neither Rucu Pichincha nor Guagua Pichincha is regularly snow-covered today, evidence of the changing climate in Ecuador. Pichincha remains an active volcano; it erupted in 1999, sending ash down on Quito.

* While the French academicians were not the first to climb Pichincha, theirs was indeed the first recorded ascent of Corazon.