![]()

THE LIFE COURSE THAT WAS PLOTTED for upper-class girls in Peru sent them down one of two paths. After six or seven years of convent school, they were expected to “take a state.” Either a girl would prepare to marry a man, or, by becoming a nun, “marry God.” This moment of decision usually came at around age twelve, the age when Catholic doctrine deemed girls to be physically capable of intercourse. However, families who did not want to wait that long to arrange a favorable union for their daughters could obtain a dispensation from the church. Child brides nine and ten years old were not uncommon in colonial Peru.

Although Creoles and Spaniards wrangled endlessly in the political arena and often confessed their loathing for one another, the parents of a Creole daughter typically put aside such feelings when it came to marriage. A Spaniard was viewed as a superior choice. Everyone understood that Creole men did not have the same access to political power that Spaniards did, and Creole men, by and large, had a reputation for being lazy, spoiled, and vain. “Creole women,” Ulloa wrote, “recognize the disaster of marrying those of their own faction.” A Spanish groom would also be certain to have limpieza sangre (clean blood), and thus a white Creole family could be assured that the offspring of such a union would enjoy the many privileges that came with being white in colonial Peru. Those of pure Spanish blood were exempt from many colonial taxes and had a privileged claim on civil and ecclesiastical positions.

Most elite families would pick older men for their young daughters to marry. Six to twelve years of age difference was the norm. At times, however, a father would contract with a forty-year-old man to wed his twelve-year-old daughter, even though this was an age difference that the girls found loathsome. They would sing:

For his money,

Money, money disappears

But the old man remains.

However, Peruvian girls did want to marry, and at an early age. A girl who passed through puberty and turned twenty years old without marrying risked being thought of as an old maid, and rumors would likely fly that she was no longer a virgin, which would make it impossible for her to ever find a husband. And while elite families looked upon an arranged marriage as a business transaction, the girls naturally had their romantic fantasies. Courtly love was part of the same knightly tradition that prompted their seclusion.

The Amadís novels that were so popular in sixteenth-century Spain were, first and foremost, romances. Although the beautiful maiden may have been locked away in her castle, kept from the world by bars on her windows, such sequestration was necessary precisely because she pined so for her knight, and did so in a feverishly physical way. These books, lamented one sixteenth-century bishop, “stir up immoral and lascivious desire.” Yet another priest lamented that “often a mother leaves her daughter shut up in the house thinking that she is left in seclusion, but the daughter is really reading books like these and hence it would be far better for the mother to take the daughter along with her.” Indeed, Spanish girls devoured the books. Saint Teresa de Jesus of Ávila confessed in her autobiography that as a child she had been “so utterly absorbed in reading them that if I did not have a new book to read, I did not feel that I could be happy.”

In Peru, this vision of romance found a real-world outlet in the amorous liaisons between men of Spanish blood and lower-caste women. As seventeenth-century visitors noted in their travelogues, Spanish men in Peru thought of mulattos and mestizos as their “women of love.” The woman who was the object of such affection was a recognized type in Peruvian society, known as a tapada. She was, American historian Luis Martín has noted, the “sex symbol of colonial Peru.”

She was always dressed in the latest fashions, and her clothing was made of the most expensive, imported materials. She favored lace from the Low Countries, exquisite silks from China, and exotic perfumes and jewelry from the Orient. The length of her gown was shortened several inches to reveal the lace trim of her undergarments, and to draw attention to her small feet covered with embroidered velvet slippers.

While upper-class girls in the convent schools were taught to assume a different role, to be honorable and chaste in their thoughts, they still were greatly influenced by this culture. Rare was the Peruvian girl, one historian wrote, who did not fancy sneaking away at night for “an amatory conversation through the Venetian blinds of the window of the ground floor.” The girls’ seclusion, which allowed their imaginations to run rampant, only reinforced this feeling. Their “frantic desire to marry,” a Peruvian scholar noted, was “aggravated still more by the ban on speaking to men, except cousins.” Moreover, even in the convents, there was an ever-present undercurrent of sexuality. All of the girls would giggle in private over the nicknames that locals gave to the pastries and candies that the nuns produced and sold—the sweets were known as “little kisses,” “raise-the-old-man,” “maiden’s tongue,” and “love’s caresses.”

As Isabel reached this moment in her life, she was by all accounts quite fetching. Petite and with delicate features, she had the slender fingers and tiny feet that men in colonial Peru so fancied. While she had the usual dark hair of the Spanish, her skin was milk-white, and in this regard, she looked very much a daughter of Guayaquil, for the women of that port city were known to be “very fair” in complexion. Those who knew her spoke of her “good soul” and of how “very pretty” she was, and of her obvious intelligence. She could speak both French and Quechua, having learned this latter language as a child, when she had had an Indian wet nurse. Even La Condamine, usually so discrete in his comments, pronounced her “delicious” upon meeting her, and remarked that she had a “provocative” mouth. He was, in the manner of the times, simply stating what everyone saw: Isabel Gramesón, who was both pretty and from a prosperous family, was going to be quite the catch.

THE FRENCH ACADEMICIANS finished their astronomical observations around Quito in April 1740, prompting La Condamine to triumphantly declare their work complete. “After four years of a traveling life, two of which had been spent on mountains, we were ready to calculate the degree of the meridian which was the purpose of so many operations.” Yet even at this apparent moment of success, they were gnawed by doubt. Their measurements of stars in the Orion constellation had consistently varied “8 to 10 seconds” from one night to the next. Although this was a small discrepancy, it still prevented them from feeling secure about the precision of their work. They had not quite reached the ambitious goal that they had set for themselves, and as they mulled over this problem, they concluded that the fault must lie with their zenith sectors. If the long telescope flexed by so much as one-sixth of an inch between viewings, a star’s apparent position would shift by twenty seconds. Everyone glumly realized what they must do: Hugo would have to make the instruments more stable or build new sectors altogether, and then they would have to repeat their celestial observations.

While waiting for Hugo to do his work, the others busied themselves in various ways. La Condamine, for his part, returned to Cuenca, intent on bringing Senièrgues’s killers to justice. He wrote to the viceroys in both Lima and Santa Fe de Bogotá,* collected statements from witnesses to the murder, and even mounted a legal case against the priest whose sermons had helped spark the riot. “I love my country,” La Condamine wrote in his journal. “I believe that I have an obligation to defend the honor and interests of my sovereign, of my nation, and of my academy.” That case seemed to stoke his appetite for other legal battles as well. La Condamine sued three individuals who had not returned goods he had loaned them, and then he got into an argument with Ulloa and Juan that also headed to court.

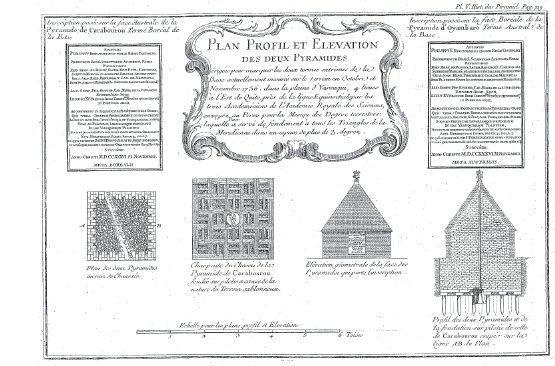

The dispute with Ulloa and Juan was over how the French planned to commemorate the expedition’s work. Even before they departed from France, they had decided to build monuments at the ends of their first baseline. This had been thought out in such detail that the academy had written the inscription that was to be used. La Condamine had taken charge of this task, and he had decided to build pyramids, rather grand in size—twelve feet by twelve feet at the base and fifteen feet tall—to mark their Yaruqui baseline. There was a scientific rationale for putting up markers, as it would enable other geodesists to check their work. But the pyramids would also serve to glorify those who performed the deed, and therein was the problem: La Condamine, as he fiddled with the wording of the inscription prepared by the academy, sought to describe the two Spanish naval officers as “assistants.”

La Condamine’s blueprint for pyramids marking the Yaruqui baseline.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur (1751).

From La Condamine’s point of view, this was exceedingly generous. None of the French helpers—Verguin, Morainville, or Jean Godin—was going to see his name on the marble tablet. But Ulloa and Juan had grown up in a society where swords could be drawn over the use of usted, and they perceived the wording as an unforgivable slight. They informed La Condamine that the inscription should describe them as Spanish academicians—they wanted equal status. Replied La Condamine: “Only the French members of the Academy were charged with this mission [and] we have always remained the masters of our work.” To describe Ulloa and Juan as academicians, he wrote, would be to award them “qualities which they did not possess.” One bemused observer of this squabble—Isabel’s uncle, the Marqués de Valleumbroso—deemed it worthy of “a new comedy by Molière.” But this was colonial Spain, and the argument blew up into a legal contest that clogged the Quito court with hundreds of documents, with the Creoles in the city cheering on La Condamine, for they rather enjoyed seeing two Spaniards humiliated.

The expedition, however, was clearly sputtering as the academicians tried to bring it to a close. The zenith sectors were in the repair shop. Louis Godin’s relationship with La Condamine and Bouguer remained so strained that more often than not they communicated with each other by letter. Senièrgues and Couplet were dead, and yet another member, Jussieu, was in bed with a raging fever, so sick that he had “put his affairs and his conscience in order.” As a group, the expedition was falling apart, and then, late in 1740, the Peruvian viceroy called Ulloa and Juan to Lima. A British armada was sailing around Cape Horn with plans to attack Peruvian ports, and he wanted the two Spaniards to help prepare the colony’s defense. The expedition, at least for the moment, had come to a halt.*

EVEN MORE THAN THE OTHER ASSISTANTS, Jean Godin was left at loose ends by this scattering of the expedition members. The others still had tasks to do. Hugo was working on the instruments, Morainville was building the pyramids, and Verguin was assisting La Condamine with his drawing of maps. But Jean’s job had been to act as a signal carrier during the triangulation work, and now there was little for him to do. Nor was there money left for the expedition as a whole. His cousin Louis was descending ever deeper into debt, while La Condamine was relying on his personal funds to pay for his expenses and for the construction of the pyramids. In order to earn some money, Jean decided to travel to Cartagena, planning to trade in textiles. Before he left, however, La Condamine gave him a trunk filled with “natural curiosities” to take to the port, where he could arrange for its shipment to France. This request picked up Jean’s spirits, for it made him feel connected, in some small way, to the others.

He departed from Quito on October 3, 1740. It was 900 miles to Cartagena, along a tortuous route that could take three months to travel. The first 500 miles involved a trek by mule across the dry plains north of the city and then along the spine of the Andes. The most treacherous segment in the mountains was Guanacas Pass, “the most famous in all South America” for its perils, Bouguer later wrote. The peaks in this region near Popayán were covered with snow, and so many mules had perished while crossing the pass that their bones covered the trail, making it impossible “to set a foot down without treading on them.” This route, Bouguer concluded, was “never hazarded without the utmost dread.”

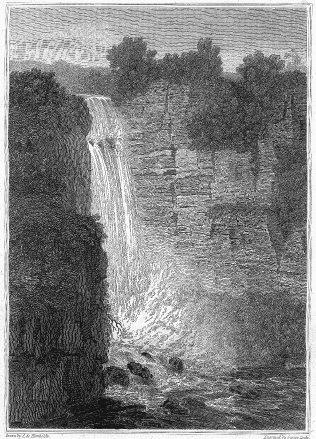

Jean Godin found it slow going; at times he was able to cover only three or four miles a day. It took him until the middle of November to make his way through the mountains and to reach the Magdalena River, where he was able to trade his mule for a canoe. This was a much more comfortable form of transport. Near Bogotá, he even took a short detour to Tequendama Falls, a waterfall “200 toises” in height that, at the time, was thought to be the tallest in the world.

When Jean arrived in Cartagena, the city was busily preparing for an attack by the British. Jean found some textiles to buy, and handed off La Condamine’s trunk to the captain of a French frigate. It contained a number of archaeological items certain to intrigue the Europeans: fossil axes, rock samples, petrified wood, the skin of a small crocodile, a stuffed coral snake, several Incan artifacts, and antique clay vases that were shaped with such skill that the water whistled when poured. Unfortunately, the ship did not sail right away and was still docked in Cartagena on March 15, 1741, when the British launched their assault. They set fire to ships in the bay, including the frigate loaded with La Condamine’s trunk of curiosities, and all of the items were lost.

Tequendama Falls.

From John Pinkerton, ed., A General Collection of the Best and Most Interesting Voyages and Travels in All Parts of the World, vol. 14 (London, 1813).

Godin’s journey to and from Cartagena took more than six months, and as had so often been the case during his time in South America, he had traveled alone. He had grown quite accustomed to this difficult life. His trek to Cartagena, he wrote, reminded him of the years he had spent “reconnoitering the ground for the meridian of Quito, fixing signals on the loftiest mountains.” But back in Quito, he was once more at loose ends. As La Condamine said, “His duties regarding the objective of our mission had ceased.” He was adrift in a Spanish colony far from his home, and it was then, over the next several months, that he became engaged to thirteen-year-old Isabel Gramesón.

There is no record of their courtship, either in Jean’s writings or La Condamine’s. The match, however, could only have been made with Pedro Gramesón’s approval, and in that regard, it was surprising. While he may have welcomed the French visitors into his home and delighted in their tales, he almost certainly would not have considered Jean Godin a good husband for his daughter. It was true that the two families shared common friends, the Pelletiers from Lignieres—alliances often lay behind arranged marriages. And Jean, during his years of service to the expedition, had proven himself to be a person of industry. But he was not Spanish and was planning to return to France, and it would hardly make sense for Pedro Gramesón to invest Isabel’s dowry in such a suitor.

His daughter, however, was strong-willed, and this was a union that would fulfill many of her wishes. She had often stated her desire to go to France. As Jean later wrote, she was “exceedingly solicitous” of traveling there. Hers was a childhood dream woven from many strands: Her grandfather on her father’s side was French, her father had entertained these famous visitors in his home, and all of Quito had gossiped about the wonders of Paris when the expedition had first come to the city. Women there, or so she had been told, presided over salons, attended the theater in fancy gowns, and danced the minuet at elegant balls. Marrying Jean promised to make all of that a reality, and at last Isabel’s father consented: He would provide the couple with a dowry that consisted of jewelry, textiles, 7,783 pesos in silver, and two slaves.

Jean and Isabel were married by Father Domingo Terol on December 29, 1741, in the Dominican College of San Fernando in Quito. La Condamine, Verguin, and Jussieu—who had recovered from his fever—all attended, as did many of the elite in Quito and other rich Creoles from miles around. The large crowd was a reflection of the Gramesóns’ prominence, particularly on Isabel’s mother’s side. It is likely that Louis Godin, Bouguer, and Morainville also attended, bringing together all the French members of the expedition one final time.

The marriage ceremony was followed by a grand feast and dance. The guests sipped on liquors chilled by ice chipped from Mount Pichincha, drank grape brandy, and ate to their hearts’ content. Great plates of fish, fowl, and meats were served, and the dining tables were loaded with bowls of succulent fruits—chirimoyas, avocados, guavas, pomegranates, and strawberries. After the food was put away, everyone danced the fandango, the rhythm tapped out with a tambourine and castanets. More than one guest had brought a guitar, and according to one account, the Gramesóns had shipped in a clavichord from Guayaquil for the occasion. Isabel’s parents had spared no expense, and everyone could see how happy Isabel and Jean looked. Theirs, it seemed, was a marriage certain to bring good fortune to both.

After the wedding, Isabel went into seclusion for a month. In a society in which the cult of the Virgin Mary held sway, it was considered improper for a woman to be seen during the time of her “deflowering.” Once the thirty days had gone by, she and Jean began a round of visits to family and friends, a ritual signaling that she had passed into adulthood. Although it was expected that Isabel, in the future, would rarely venture out alone—social protocol required that she have a maid or her husband with her—she no longer needed to be to be hidden. She was fourteen years old and he was twenty-eight, a match that seemed right and proper to all, and even as they made their social rounds, she was already pregnant with their first child.

During this period, La Condamine, Bouguer, and Louis Godin repeated their celestial observations, but without success. Hugo’s repairs to the zenith sectors did not make any difference. A star’s zenith position would vary from five to twenty seconds from night to night. They now had to confront a painful possibility: Perhaps they were trying to do the impossible. Perhaps they could not measure a degree of latitude with sufficient precision to definitively answer the question of the earth’s shape. They were sure that Maupertuis’s measurements in Lapland were not as accurate as theirs already were, and yet they knew that if they went ahead and used these imprecise celestial observations to calculate the length of a degree of latitude at the equator, some doubt would remain.

There were any number of factors that might be causing the variation. Perhaps, they speculated, atmospheric refraction was not constant. Perhaps its strength varied from night to night. Or perhaps the adobe walls of their observatories contracted or expanded ever so slightly in response to changes in temperature and humidity, which in turn caused a slight movement in the wire strung up to align the zenith sector along the meridian plane. Or could the star’s position actually be changing? Maybe, in their effort to make measurements more precise than anyone had ever made before, they had discovered something new about the universe: A star’s movement through the heavens might not be quite as fixed as previously believed. Perhaps a star could wobble. They mulled over all these possibilities and then, in late 1741, Bouguer wrote La Condamine with “devastating” news. He had concluded that the problems with their two zenith sectors had never been resolved. Hugo would have to make additional improvements to one of the sectors and build a second one anew. Sighed La Condamine: “At a time when I was flattering myself that all of the obstacles that had been holding us back for so long were going to be removed and that I could finally set off en route back to France, I found myself forced to begin the work again. Although it was painful, it was clear to me that our work was not nearly done.”

As frustrating as this all was, the problems with the zenith sectors enabled La Condamine and Bouguer to pursue other investigations, which turned out to be very fruitful. La Condamine took advantage of the hiatus to travel with Pedro Maldonado along his newly opened road to Esmeraldas. In 1736, La Condamine had stumbled through the rain forest along this route, but now the journey could be fairly easily made. This was progress, and once La Condamine was back in Esmeraldas, he happily renewed his study of a thick, white liquid called caoutchouc, which Indians took from the hevea tree. On his first visit to Esmeraldas, he had noticed that local Indians poured caoutchouc between shaped plantain leaves, let it harden, and then used it “for the same purpose we use waxcloth.” La Condamine fashioned a waterproof pouch for his scientific instruments from this amazing material, sent back samples of it to France, and, in collaboration with Maldonado, wrote a monograph on its properties, helping to introduce rubber to Europe. La Condamine also came upon an Indian tribe that used a curious white metal to make jewelry, and when metallurgists in France received a sample of it from him, they immediately saw that this “platinum” was going to be very useful. La Condamine was in his element again, mining the New World for plants and minerals—quinquina, rubber, platinum—that would, in the years ahead, lead to important advances in medicine and industry.

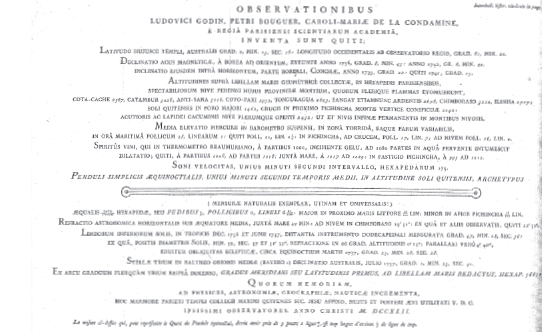

He and the others chalked up numerous achievements during this time. After his trip to Esmeraldas, La Condamine collaborated with Verguin and Maldonado to produce a map of the Quito Audiencia that was far more accurate than any that had been drawn before. With Bouguer, he continued conducting experiments on the speed of sound and on the expansion and contraction of materials in response to temperature changes. The two observed solar and lunar eclipses, calculated the “obliquity of the ecliptic”—the tilt of the earth toward the sun—and investigated the strength of the magnetic attraction to both poles. “It matters not on what place of the earth we stand,” Bouguer concluded, “we shall always feel the action of one pole as powerfully as the other.” Perhaps most important of all, La Condamine came up with the idea of using the “length of a seconds pendulum at the equator, at the altitude of Quito” as a “natural measurement.” This would be a ruler defined by the gravitational pull of the earth rather than something arbitrary like a king’s foot, and it could provide a standardized measurement for all nations. “One wishes that it would be universal,” La Condamine wrote, giving voice to a sentiment that, fifty years later, would inspire France to invent the meter.*

As a final adventure, La Condamine and Bouguer climbed the Pichincha volcano in June 1742. The crater was about a mile away from the summit where they had camped in 1736. They struggled once again with the elements, and at one point, La Condamine, while hiking apart from Bouguer, became lost. The night closed in on him, he was soaking wet and his feet were stuck in the “melting snow,” and once more he showed how resourceful he could be:

I tried in vain to keep moving my feet so as to provide them some heat and by around four in the morning I could no longer feel them at all and feared they had frozen. I remain convinced that I would not have escaped this danger, which was difficult to foresee when setting off for a volcano, if I had not come upon a successful solution involving the bathing of my feet in a natural bath, the nature of which I shall leave to the reader’s imagination.

After returning from that climb, La Condamine and Bouguer were ready to say their last good-byes to Quito. Hugo had reengineered their sectors for one final round of celestial observations. Bouguer would go north to their observatory at Cotchesqui (near Yaruqui), while La Condamine would head south to Tarqui. They planned to make simultaneous observations of the same star and exchange results by messenger. After they were done, Bouguer intended to head to France via Cartagena, while La Condamine was planning to go down the Amazon. Only a few had ever traveled from the Andes to the Atlantic coast via this great river, and certainly no scientist ever had. Pedro Maldonado was contemplating joining him, although his friends and family were begging him not to go, warning him that it was much too dangerous.

By this time, both of La Condamine’s legal imbroglios had concluded, although not quite to his satisfaction. A year earlier, he had won a victory in his pursuit of Senièrgues’s killers, the Quito prosecutor in the case deciding that he would seek the death penalty for Leon, Neyra, and Serrano. However, that decision had not been at all popular in Cuenca, and when authorities had tried to arrest the killers, only Leon could be found and put in jail. The Quito court subsequently pronounced the three guilty but commuted their death sentences to eight years of exile, a decision that everyone in Cuenca could accept because, as La Condamine bitterly wrote, “no one obeyed it.”

The war of the pyramids, as locals called La Condamine’s dispute with Ulloa and Juan, had come to a similar confused end. After his initial argument with the two Spaniards in 1740, La Condamine had erected the monuments without listing their names, since they had insisted on being described as academicians. He also carved a fleur-de-lis, the French coat of arms, on the two pyramids, which of course brought him more trouble. In late 1741, Ulloa and Juan had made a brief visit to Quito, and when they discovered that the pyramids had been built in this manner, they filed suit, arguing that the inscription and presence of the fleur-de-lis “insulted the nation of Spain and his Catholic Majesty personally.” The first judge to review the case ordered the pyramids destroyed. A second judge set that order aside and ruled that the inscription had to be changed—the names of the two Spaniards had to be added and they were to be described as participants, not assistants. In addition, the judge ordered La Condamine to carve the escutcheon of the Spanish monarchy above the French coat of arms. But that was not the end of the matter. On July 10, 1742, the Quito Audiencia issued a third decision: The escutcheon and the names of Ulloa and Juan were to be inscribed, but La Condamine would be allowed to call them assistants. This lengthy court battle led Isabel’s uncle to quip that “justice in Quito is constant and perpetual because the trials never end,” and indeed, the Quito Audiencia also sent the matter to the Council of the Indies in Madrid for further review.*

In late August, La Condamine wrapped up a few last matters in Quito. He had a bronze ruler made that was the length of a seconds pendulum at the equator, which he placed into a marble tablet and gave to the Jesuits. This commemorative, humble in kind, was eagerly welcomed. He also sold his quadrant, and in order to do the same with his tent, he set it up in Quito’s plaza mayor, a spectacle, he reported, that “attracted the attention of the ladies of the city, which I had foreseen and whom I was pleased to honor.” Even at this moment of good-bye, the rich women of Quito still viewed the French expedition through romantic eyes.

La Condamine and Bouguer spent the next six months in their respective observatories, and this time they found that their zenith measurements were consistent from one day to the next. Their instruments were working well, and when they exchanged letters in early 1743, it was evident that at last they had a cohesive result. The two ends of their meridian were three degrees, seven minutes, and one second apart in latitude. Since their meridian was 176,940 toises long, this meant that the distance of one degree of arc was 56,749 toises (68.728 miles). There could be no doubt now about the earth’s shape. Maupertuis had found that an arc of meridian in Lapland was 57,497 toises. A degree of arc clearly lengthened as one went north from the equator, proving, La Condamine wrote, “that the earth is a spheroid flattened toward the poles.” Newton—and not the Cassinis—had been right.

Louis Godin, Ulloa, and Juan finished their celestial observations a year later. The War of Jenkins’s Ear fizzled to an end, allowing the two naval officers to return to Quito and resume working with Godin, and the trio concluded that a degree of arc at the equator was 56,768 toises. This was only nineteen toises different from the number obtained by La Condamine and Bouguer; the similarity of the results was evidence that both groups had done their work well. Indeed, more than 200 years later, geodesists would find that their measurements were amazingly accurate, much superior to the ones Maupertuis had made in Lapland.

La Condamine’s inscription on a marble tablet advocating the use of the seconds pendulum as a universal measurement.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur (1751).

So much had happened that would have caused lesser men to give up. As Ulloa wrote, theirs had been a mission marked by a “series of labors and hardships, by which the health and vigor of all were in some measure impaired.” But they never had, and the fact that they had kept on until they achieved these results spoke volumes about their character. La Condamine and the others may have been deeply flawed human beings—often vain, fractious, and petty—but they had proven themselves to be men of resolve and courage, Enlightenment scientists through and through.

* Santa Fe de Bogotá was the capital of the Viceroyalty of New Granada, which Spain had created in 1717, carving it out from the northern part of the Viceroyalty of Peru. The Quito Audiencia was shifted out of Peru and into Granada in 1739.

* The War of Jenkins’s Ear had its roots in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, when Britain obtained the right to have one British merchant ship a year trade with Spain’s New World colonies. That very limited right blossomed into a much larger English smuggling enterprise, which the Spanish Guardias Marinas was constantly trying to rein in. In 1731, Spain detained a British ship, captained by Robert Jenkins, that was allegedly loaded with contraband. Jenkins insulted the Spanish commander, who responded—or so the story went—by cutting off Jenkins’s ear with a sword, spitting into the severed organ, and vowing that he would like to do the same to England’s King George II. In 1738, Jenkins recounted his tale to the House of Commons, even presenting to them his carefully pickled ear, and the furor was such that England declared war on Spain.

* The meter is also a “natural measurement,” for it was defined as one-ten-millionth of the distance from the equator to the North Pole.

* In 1747, the Spanish Crown ordered the pyramids destroyed. As a result, the exact location of the baseline was lost. In honor of the 100-year anniversary of the La Condamine expedition, Ecuador rebuilt the pyramids in 1836, but it lacked the information to erect them on the proper spot.