![]()

THE SANDBAR THAT ISABEL’S PARTY was stranded on was perhaps 200 feet wide and several hundred yards long. They had built their hut, as Rocha later told the priest at Andoas, “at the top of the beach, located in a way that it could not have been more insulated from the growing river.” They had also woven palm fronds together into beds, which made their rancho, as such beach shelters were called, at least somewhat comfortable. They were, however, surrounded by a wilderness that they did not dare enter. They were now in the very part of the Amazon basin that is most inhospitable to humans.

Much of the Amazon rain forest is relatively benign and not overly difficult to walk through, as long as one is equipped with a compass or is on a path. The dense canopy blocks out so much sun-light that there is only a sparse amount of vegetation on the forest floor. Leaves and other plant debris that fall to the ground are quickly chewed up by hordes of ants and beetles, and while there are poisonous snakes and other dangers in a rain forest of this type, they are not so overwhelming as to chase all humans away. Even the mosquitoes and bugs are not too nettlesome in a mature rain forest. But the forests along the lower Bobonaza, where Isabel and her party were stranded, are a different case. At this point, the river’s descent from the Andes is over, and as it spills into the huge lowland that is the Amazon basin, it turns the landscape into a marshy swampland.

The jacumama that Ulloa and Juan wrote about, cautioning that this “man-eating serpent delights in lakes and marshy places,” is known today as the great anaconda. Growing to as much as thirty feet long and weighing as much as 500 pounds, it lies in wait along the river’s edge and in lagoons, feeding—in the eighteenth century—on a bountiful supply of capybaras, large birds, peccaries (a piglike animal), 400-pound tapirs (a hoofed mammal), and young caimans. The constrictor kills by coiling itself around its prey and strangling it.

The poisonous snakes that haunt the banks of the lower Bobonaza are of two kinds: coral snakes and pit vipers. The corals are recognizable by their red and yellow bands warning predators to stay away. Their powerful venom can cause heart and respiratory failure. The poison from the fangs of pit vipers, which have distinctive triangular heads and catlike eyes, kills by rapidly destroying blood cells and vessels. Most pit vipers, such as the fer-de-lance, hide coiled beneath forest-floor debris. However, the palm pit viper likes to hang from a branch, looking for all the world like a dangling vine, remaining perfectly still until striking out at any passing bird or warm-blooded animal that mistakenly brushes up against it. During October and November, snakes on the lower Bobonaza also tend to be on the move, for this is the season in which they shed their skins and travel to new holes.

Jaguars still roam this region as well, although not in the numbers they did in the eighteenth century, when they were called “tigers” by the Spaniards. They prowl the rivers and marshes, hunting monkeys, tapirs, peccaries, capybaras, and juvenile caimans. Their prints are often found on sandbars. At times, in the early morning hours, a jaguar still full from a night of successful hunting will stretch out on a log floating down a river, catching some sun.

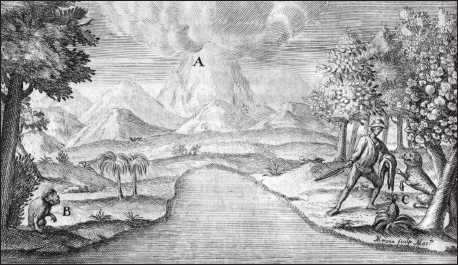

An explorer fights a “tiger” in the jungle.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional (1749).

Even the river harbors a host of threatening creatures. In the lower Bobonaza, there are electric eels that can deliver a 650-volt jolt, blood-sucking leeches, stingrays with venom-laced tails, and a bizarre catfish called the candiru. Thin as a catheter, the candiru has the nasty habit of swimming up body orifices—the human urethral, vaginal, or anal opening—where it fixes itself by opening an array of sharp fin spines, triggering almost unendurable pain.

Isabel and the others, having been warned about all these dangers, clung to the sandbar. They were prisoners of their little spit of beach, near a spot on the Bobonaza known today as Laguna Ishpingococha. Their days quickly settled into a routine. They would awaken at the first break of light, often to the sound of monkeys chattering in the nearby trees. This was the best hour of their day. The light was soft and the air relatively cool, the temperature having dropped to seventy-five degrees Fahrenheit or so during the night. Herons, swallows, and other river birds swooped about, and across the way, there was a beautiful ceiba tree in flower. All of the leaves had dropped from its majestic crown, and its seeds would drift across the water, held aloft by silky, cottonlike fibers. Isabel and the others would eat upon rising, taking from their supplies a serving of dried potatoes or corn or a small piece of jerky.

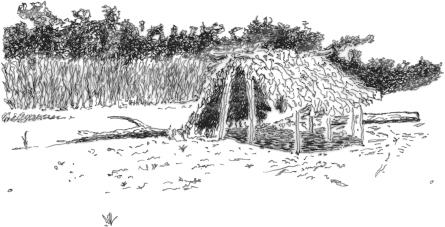

A hut on the lower Bobonaza.

Drawing by Ingrid Aue.

As the sun rose, however, the air would turn humid and oppressive. By midday, the sand would be hot to the touch, so much so that it would be difficult to cross barefoot. There was nothing for them to do but hide out in shade of their hut, no one saying much of anything. More often than not, the heat would give way to an afternoon rain, and when the rain ceased, the sand flies, gnats, and mosquitoes would come out. These insects pestered them as they pestered all who came through here: Isabel and everyone else scratched their bites, which became infected, their legs in particular becoming covered with the painful sores.

At dusk, the jungle would begin to resonate with the nerve-racking shrieks of howler monkeys and the whoosh-whoosh of bats—sounds that had become familiar and yet were still unsettling. And as night fell, Isabel and the others would struggle to put down thoughts of caimans, jaguars, and snakes creeping through the darkened foliage, only a few yards away from their hut. They worried too that the Jibaros would discover their campsite and swoop down upon them while they were sleeping. Although the Quechua Indians in Canelos and Andoas were not to be feared, the Jibaros were, and they were known to haunt both sides of this river. When Spruce came to this region, his Quechua guides slept with “lances and bows and arrows at the head of their mosquito nets, so as to be ready in case of an attack,” while Spruce would only “go ashore with firearms.” The Jibaros were the “naked savages” that La Condamine had written about, a tribe said to “eat their prisoners.”

Isabel and the others passed a week in this anxious manner, and then a second. As the days passed, they began to grow weaker, the heat sapping their strength. During the long midday hours, they would all rest in the shade of their hut, and even though their throats would become parched with thirst, nobody would stir, as though the trip across the sand to the river would be too taxing. The jungle, meanwhile, was literally closing in on them: The rising river had narrowed their beach. Their clothing was rotting and disintegrating in the humidity, their insect bites were turning into open, festering sores, and with each passing day it seemed increasingly evident that nobody was coming back for them. They were notching a stick to count the days, but after a while, they were no longer certain just how much time had passed. Had they remembered to cut a notch the day before? They could not be quite sure, for the days merged one into another. In their confusion, they would add another notch to their stick, and in this manner—as later became clear—they became too quick with their calendar. As a result, sooner than they should have, they lost all “confidence that help would come.”

By their count, that moment of total despair arrived “five and twenty days” after the others had left. Rocha had promised that he would return in two weeks, three weeks at most, and yet their calendar stood at November 28. They remembered too that he had taken all his things with him. Their food supplies were nearly gone—clearly, they could not stay on the sandbar much longer. Faced with such facts, Isabel and her two brothers made a fateful decision: They would build a raft. They had both a machete and an ax, and fighting now for their lives, they entered the jungle, hacking away at the few slender trees they could find and dragging them to the sandbar. After cutting the poles to the same length, they lashed them together with lianas. This fragile craft would have to carry them more than ninety miles to safety.

The raft, however, was not big enough to take everyone. Again, they decided to split up. Isabel, her two brothers, and her nephew Martín would go ahead, while Rocha’s slave Antonio would stay behind with Isabel’s two maids, Juanita and Tomasa. The two girls were only eight or nine years old, and Antonio would watch over them, with the hope that a rescue party would soon arrive. Either Rocha and Joaquín would finally return, or Isabel and the others would make it safely to Andoas and send a canoe back upriver.

Neither option—staying or going—had much to recommend it. This was a plan born of utter desperation and perhaps delirium. Everyone had grown weak and confused on the beach, and things quickly went awry. No sooner had Isabel and the others clambered onto the raft than it began swirling out of control in the river, Juan and Antonio struggling desperately with their two long poles to keep it headed in the right direction. Then disaster struck: “The raft,” as Jean would later write, “badly framed, struck against the branch of a sunken tree, and overset, and their effects perished in the waves, the whole party being plunged into the water.”

This time, there was no overturned canoe to grab onto. Isabel, still in her heavy dress, gulped for air and went under, her arms flailing as she struggled to keep from drowning. Those who had been left behind on the beach were screaming, helpless to do anything. Then Isabel felt a hand grab the back of her dress, pulling her momentarily to the surface. A burst of air flew into her lungs, then she plunged once more beneath the water, into a tangle of branches and debris. Her mind exploded in panic until yet again she felt a hand reaching for her, pulling her up and toward the bank. “No one was drowned,” Jean wrote, “Madame Godin being saved, after twice sinking, by her brothers.”

Frightened and muddy, they made their way back to the sandbar. The provisions they had placed aboard the raft were gone, putting them “in a situation still more distressing than before.” Although the wise decision surely would have been to resume waiting there, they felt they had to do something. “Collectively,” they “resolved on tracing the course of the river along its banks.” Isabel, her two brothers, and Martín would try to walk to Andoas. Antonio, Juanita, and Tomasa would once again stay behind, and if rescue of any kind happened by—perhaps a Quechua Indian would come downriver, or perhaps a search party from Andoas would indeed at last be sent—they could tell it to look for Isabel and her brothers, who planned to stay close to the river’s edge.

In preparation of the long trek ahead, Isabel changed out of her dress and into an extra pair of her brother’s pants. Even in that desperate hour, the sight of Isabel wearing a pair of men’s pants was startling: No one had ever seen a woman so dressed. They packed up the ax, the machete, and a portion of the remaining provisions. Their supplies were so low that they would only have enough food for a few days, and then they would have to forage for something to eat. Their minds were set, and without any further hesitation, Isabel, her two brothers, and Martín—all of them already weak and exhausted—plunged into the jungle.

HAD ISABEL AND HER BROTHERS possessed a map and a compass, along with supplies, it would have been feasible for them to walk to Andoas. They would have needed to walk away from the river, out of its swampy environs to slightly higher and drier land, and then make a beeline to Andoas, which was about seventy-five miles away as the crow flies. But their plan to follow the river—something that only a mountain-dweller would think of trying—was doomed to fail. The lower Bobonaza twists and turns as it makes its way across this lowland, heading north one moment and south the next, the river carving out huge, slow oxbows, such that one could walk several miles along its banks and end up only a few hundred yards further to the east. Even worse, the vegetation was so thick that they had to hack through it with their machete, which wore them out and slowed their progress. “The banks of the river are beset with trees, undergrowth, herbage, and lianas, and it is often necessary to cut one’s way,” Jean Godin wrote. “By keeping along the river’s side, they found its sinuosities greatly lengthened their way, to avoid which inconvenience they penetrated the wood.”

Although they were now out of the swampiest areas, they found it impossible to orient themselves in the darkened rain forest. The thick canopy of trees filtered out most of the light. They could not see more than twenty or thirty feet in any direction, the landscape a chaotic mix of shadows and otherworldly shapes. Many of the trees rose from a tangle of aboveground roots, as though they were ready to begin walking around on stilts. Vines and creepers were everywhere, climbing up tree trunks and dripping from the canopy. Even the palm trees had whorls of sharpened spikes around their trunks, a form of armor in this fierce landscape. This gloomy, foreign place was the very world that haunted their imaginations—this was where they had “lost themselves”—and every night, as dusk fell, mosquitoes, flies, and other insects came out in droves, tormenting them in a most physical way.

A nineteenth-century illustration of a primeval forest in the Amazon.

Private collection/Bridgeman Art Library.

Nineteenth-century explorers who spent any length of time in this type of Amazonian terrain—wet jungle away from the confines of a river—inevitably complained of how utterly intolerable it was. When Spruce explored the forest bordering the Pastaza, in the area around Andoas, he could bear it only for a few hours. “The very air my be said to be alive with mosquitoes. … I constantly returned from my walk with my hands, feet, neck and face covered with blood, and I found I could nowhere escape these pests.” Similarly, Humboldt, while traveling through landscape of this kind in the early 1800s, reported that the insects could drive one mad:

Without interruption, at every instant of life, you may be tormented by insects flying in the air. … However accustomed you may be to endure pain without complaint, however lively an interest you may take in the objects of your researches, it is impossible not to be constantly disturbed by the moschettoes, zancudoes, jejens, and tempraneroes, that cover the face and hands, pierce the clothes with their long sucker in the form of a needle, and, getting into the mouth and nostrils, set you coughing and sneezing whenever you attempt to speak in the open air.

As pervasive as the flying insects can be, the insects that march on the forest floor—the many species of ants—are even more so, their vast numbers sustained by the voluminous leaf litter. Ants are so numerous in a lowland rain forest that collectively they may outweigh all the vertebrates inhabiting it. As the American biologist Adrian Forsyth found, ants in this environment never leave a person alone:

No matter where you step, no matter where you lean, no matter where you sit, you will encounter ants. There are ant nests in the ground, ant nests in the bushes, ant nests in the trees; whenever you disturb their ubiquitous nests, the inhabitants rush forth to defend their homes.

One of the most painful nonlethal experiences a person can endure is the sting of the giant ant Paraponera clavata. These ants, with their glistening black bodies over an inch long, sport massive hypodermic syringes and large venom reservoirs. They call on these weapons with wild abandon when provoked, and they are easily offended beasts.

The catalog of bothersome insects in a lowland rain forest is endless. There are giant stinging ants, ants that bite, and ants that both bite and sting. People who have been attacked by the notorious “fire ants” describe the pain as exactly like “reaching into a flame.” The sting from one of Forsyth’s “bullet ants” is said to be like a “red-hot spike” that produces hours of “burning, blinding pain.” Colonies of wasps and bees abound, and there are many scorpions and tarantulas. Chiggers fasten onto the legs of passersby who brush against the vegetation, and their saliva contains a digestive enzyme that dissolves the surrounding flesh, producing, as one traveler wrote, “raging complex itches that come and go for days on end.” The assassin bug is a nasty bloodsucker that bites people around the mouth or on the cheek (and thus is sometimes known as the kissing bug), and even caterpillars in his lowland forest can be menacing. Many, the naturalist John Kricher writes, “are covered with sharp hairs that cause itching, burning and welts if they prick the skin, a reaction similar to that caused by stinging nettle.”

This was the landscape in which Isabel, her two brothers, and her nephew were now stranded. During the daylight hours, they tried to keep moving, usually in single file, with either Juan or Antonio in the lead, the other at the rear, and Isabel and Martín in the middle. They would walk and walk, and then they would have to stop to rest, drained by the heat and humidity. They would drink their fill of water at a stream, and at last they would pull themselves to their feet and wander some more, until their throats thickened again with thirst. They were not trying to go in any particular direction, they were just trying to keep moving, hoping that they would stumble back upon the Bobonaza. Then, as dusk fell, the insects would come out, and there was absolutely nothing they could do to protect themselves from this onslaught. They had no ointments, no mosquito nets, no tents—only the clothes they were wearing and several shawls, which they would desperately wrap around their faces and hands. But it was futile. The insects feasted on them, and even the full darkness of the night did not bring them relief. They would huddle together in the blackness, perhaps leaning against a fallen branch or against a large tree trunk, and hordes of ants would begin their onslaught, crawling over them, under their pants and over every inch of exposed skin. This would be their lot for twelve nightmarish hours, and then the pitiless cycle would begin all over again.

During these awful days, they were plagued in particular by mosquitoes laden with botfly eggs. A botfly will stick its eggs to a passing mosquito, and when the mosquito feeds on an animal, the animal’s body heat causes the eggs to hatch. The larvae then burrow beneath the skin. A botfly maggot has two anal hooks that anchor it firmly in its new nest, and there it grows for more than a month, causing discomfort in its host every time it turns because its body is covered with sharp spines. At last, it emerges as an inch-long worm, ready to pupate and begin its life as a botfly. Monkeys in the lowland rain forests of the Amazon can be so parasitized by botflies that they die from them. And that was now happening to Isabel, her two brothers, and young Martín. They were taking their turn as food for the botflies of the Bobonaza forest, even as they were slowly starving to death.

THE FERTILITY OF THE RAIN FOREST, with its profusion of plants and wildlife, suggests that it should be an easy place to forage for food. Orellana and Acuña, after their voyages down the Amazon, reported that Indians living along the banks had bountiful supplies of food, raising turtles in pens, growing manioc, fishing, and hunting the abundant game. But their mastery over the environment had been achieved over the course of 10,000 years, and in a part of the Amazon basin that was much more habitable than the swampy lowlands near the Bobonaza. Wild Jibaros of the eighteenth century may have hunted in these lowlands, but they built their villages on drier ground, further upriver. Even in that more hospitable environment, nearly all of the available food—other than game—is out of reach, in the top part of the canopy. At ground level, there is little to harvest. Trees and plants are in such fierce competition for light and space that they are armed with a panoply of defenses to prevent their leaves and bark from being consumed.

The foremost of these are chemical toxins, mainly phenolics, tannins, and alkaloids; this last group is experienced by humans as analgesics, stimulants, and hallucinogens. In the wild, they serve to discourage insects from feeding on a plant’s leaves. As one naturalist has written, the caffeine that we find stimulating and enjoyable “is in reality a form of insecticide.” Indigenous tribes in the Amazon use these compounds in their shaman medicine and also, as La Condamine discovered, as poisons with which they hunt and fish. In addition to an array of chemical defenses, tropical plants may have spiny leaves and jagged stilettos on their trunks to ward off insects. These daggers are in turn covered by lichens and microbes that can easily cause an infection.

As a result of this plant warfare, the food cycle in the rain forest is an unusual one. High up in the canopy, there may be an abundance of fruit and nuts that can be consumed, since plants may depend on animals to spread their seeds. The fruits and nuts are feasted on by monkeys, sloths, bats, birds, insects, and other denizens of the treetops. But lower down in the rain forest, there is little food available for ground-dwelling herbivores. Most of the ground animals either consume dead vegetable matter, as ants and termites do, or feed on fish, birds, monkeys, and other meat-eaters, with the jaguar at the top of this particular food chain. The American biologist Victor von Hagen, who lived among the Jibaros in the upper Amazon during the 1930s, described how impossible it is to forage for food in this environment:

All that the primitive has, he has cultivated from indigenous plants in the forest. These he has grown since time immemorial. The jungle yields, in its wild state, practically nothing. To be explicit, there are only four or five foods that may be obtained, irregularly from bountiful nature, and none of these can sustain man, brown or white, over an extended period of time.

One of the few edibles that can be found in the Bobonaza watershed is the palm cabbage, and that is what Isabel, her two brothers, and Martín were “fain to subsist on,” along with “a few seeds and wild fruit.” After their food ran out, they spent all their daylight hours in search of something to eat. They would fall upon a palm cabbage as though it were a feast, and then they would resume their hunt. Yet they were growing ever more gaunt, and each succeeding day their “fatigue” and their “wounds” increased. “Thorns and brambles” tore at their flesh and clothing, and the insects never let up; every inch of their bodies was covered with bites, which were horribly infected. The jungle was killing them in a thousand small ways.

They struggled in this way for three weeks, and then a fourth. They were still on their feet in late December. They kept on finding just enough food to keep going a little longer, wandering for a few hours each day to hunt for palm cabbage and then moving on to a new spot, until at last, “oppressed with hunger and thirst, with lassitude and loss of strength, they seated themselves on the ground without the power of rising, and waited thus the approach of death.”

THE PROCESS OF DYING from starvation is fairly well understood. At first, the body is able to draw on stored carbohydrates and fats as a source of energy. Liver glycogen, which is how the body packs away carbohydrates for emergency use, is broken down to maintain blood glucose levels. Once the glycogen stores are depleted, the body begins to break down muscle tissue to extract amino acids that can be used to make glucose. At the same time, with glucose in such short supply, the body begins to utilize an emergency energy source, ketones synthesized by the liver from fatty acids. The body’s metabolism slows down as well, and the starving person becomes ever more lethargic. Toward the end, speech becomes slurred, and all of the senses start to fail: Hearing dims, eyesight fades, and smell disappears, the body progressively consuming itself until death arrives.

This was the point of near-death that the Gramesóns had reached. As they lay on the forest floor, too weak to move, all except Isabel, who retained a certain strength, slipped in and out of consciousness. Isabel did what she could to care for her brothers and her nephew, whose pain during these final hours came not from their hunger but from their thirst. The humidity of the jungle drew water from their parched bodies just as it drew moisture from plants, and there, in a rain forest of all places, their agonies were increased by the torments of dehydration. As their saliva dried up, horrible lumps formed in their throats, which they were unable to dislodge no matter how many times they swallowed. Their tongues thickened so much that they gasped for breath. It was as though they were dying not from hunger or even, in the very end, from thirst but from suffocation.

Martín was “the first to succumb.” Isabel cradled him in her arms, for she still had the energy to sit, with her back against a tree. Their unlucky fate was such that hardly any rain came in those last days, but when it did, Isabel soaked up the water with her shawl and used it to moisten Martín’s forehead and his lips. Her nephew looked so old. His skin had turned purplish, and his eyes had sunk ever deeper into his skull. He seemed to be pleading with her, but he was too weak to speak, the only sound escaping from his lips a low moan. At last his eyes closed, he groaned slightly as his lungs fought for one more breath, and he was gone. His father Antonio and his uncle Juan expired in similar pain over the course of the next couple of days, and then Isabel, having “watched as they all died,” awaited “her own last moments.”

Because women have a higher percentage of body fat, they tend to outlast men in starvation situations.* Isabel was also short and middle-aged, both factors that affect metabolism in ways that allow a starving person to live a little while longer. And for two days more, Isabel lay “stretched on the ground by the side of the corpses of her brothers [and her nephew], stupefied, delirious, and tormented with choking thirst.” All of the flies and insects of the forest had descended on the three rotting bodies, and they swarmed over her too. She was little more than a living corpse, and she desperately wanted to die. Yet even as she prayed to God for relief, for an end to her suffering, images of Jean began to flit in and out of her mind. At one point, she thought she could hear him calling to her. She was hallucinating, of course, yet it seemed so vivid, and in those moments she felt a surge of willpower, a desire to live. God was sparing her, it seemed, and a boat was waiting to take her to her husband. She was thirsty, she needed to “look for water,” and suddenly a single thought was pushing loudly to the front of her mind: Get up.

At last, as Jean would later write, Isabel gathered the “resolution and strength” to stand. Her “clothing was in tatters” from the many weeks in the jungle, her blouse so torn to shreds that she was nearly naked from the waist up. Her shoes too were gone. After steadying herself, she saw clearly what she had to do. Taking the machete in hand, she knelt next to the decaying corpses. Antonio’s shoes would now be hers. She “cut the shoes off her brother’s feet,” and hacked away until she had converted them into sandals. Seeing that her clothing was “all torn to rags,” she “took her scarf and wrapped it around herself.” And then Isabel Godin, who only three months earlier had departed from Riobamba dressed in silk, disappeared into the forest.

BY THIS TIME, a rescue canoe had long since come and gone from the sandbar where Isabel and the others had been stranded. The scene that Joaquín had found there was as gruesome as the one in the forest. He, Rocha, and Bogé had successfully reached the mission station in Andoas on November 8, “at four in the afternoon.” The resident priest, Juan Suasti, was not there when they arrived, as he was off visiting a village further downriver called Pinchis, and it took Joaquín at least two days, and possibly three, to pull together a crew of Indians willing to go upriver to rescue those left behind. Rocha and Bogé declined to go back, seemingly indifferent to the fate of Isabel and the others, which caused Jean to later write bitterly that Rocha thought “more of his own affairs than forwarding the boat which should recall his benefactors to life.”

Because they had to row against the current, it took Joaquín and the Andoas Indians fourteen days to reach the sandbar, more than twice as long as it had taken Joaquín, Rocha, and Bogé to come downriver. Suasti described what happened next:

Filled with hope, they jumped onto the land, the slave [Joaquín] with greater energy than the Indians. But they found no one living. The slave entered the rancho where they had left everyone, and found there the beds of straw strewn about, the clothes scattered about the beach, some human bones without meat on them in the forest, and a cadaver in a dip in the river, without much vestige of a person. There was a balsa raft leaning on the side of the river, and on the bank they could find perhaps the footsteps of three persons.

Joaquín and the Indians arrived at the sandbar on November 25, and thus the tragic timeline: Isabel and her family must have departed just a few days earlier, and then those staying behind—Juanita, Tomasa, and Antonio—were killed by marauders of some kind from the jungle. Although the cadaver in the river was badly decomposed, Joaquín thought that perhaps it was Antonio, Rocha’s slave. But he also found reason to hope that not all had died. The pile of human bones in the forest was not very big, and there were footprints in the riverbank by the raft, suggesting that several in the group had tried to go on. He ordered the Indians to scour the woods “on both sides of the river to see if they could find some trail,” and he too went in search of his beloved mistress. He was a slave but also a Gramesón—in the culture of eighteenth-century Peru this was his family—and he walked through the wilderness for four days, calling out Isabel’s name every few seconds. He and the Indians searched five or six miles inland, on both sides of the river, but, as Suasti wrote, “all these efforts were in vain.”

Before departing from the sandbar, Joaquín took an inventory of the items strewn about the beach. Everything that had been there when he had left on November 3 was still to be found, except for the “ax and machete” and a pair of “old trousers.” But Isabel’s jewelry and silverware were still there, as were her fancier clothes, such as a “velvet petticoat,” and these items he gathered up, intending to bring them to her father, who was waiting in Loreto. On the way back to Andoas, they traveled slowly, regularly stopping so that the Indians could hunt for footsteps or any sort of trail in the woods. They spent two weeks making their way downriver in this halting manner, arriving back in Andoas shortly before December 15. Joaquín and the Indians told Suasti what they had found, and he, in turn, summed up the “sad” news for authorities in Quito:

They were not able to verify the cause of such a lamentable event because they had not found even one person of the [Gramesón] family, and with the countryside being so harsh, with forests empty of all human commerce. The most reasonable Indians formed some ideas of what had happened. They believed that three or four days after the family had been left behind on the beach, they were ravaged either by barbaric Indians or by the fierce tigers that are abundant in these woods. To support the first judgment, they note that they had found in the hut all of their clothing and even their undergarments, which led them to conclude that the infidels killed them during the night, while they were sleeping, killing them all and throwing them into the river.* Plus they found a body torn to pieces in the river. The same facts could support the second possibility. Being terrorized by tigers, or something else preying on them, they were filled with dread and shock and inadvertently they threw themselves into the river [and drowned], and some of them could also have fled, taking the balsa raft, getting on it and also drowning. All of the Indians and the Negro that went to look for the señora answered with this declaration and swore on the cross that it was true.

Having written up his report, Suasti told Joaquín to carry it to his superior in Lagunas and to the governor of the Maynas district, Antonio Peña, who was located in Omaguas, near the border with Brazil. Suasti entrusted Isabel’s belongings to Rocha, requesting that the Frenchman deliver the jewelry, silverware, and other items to Isabel’s father. Rocha, Bogé, and Joaquín arrived in Lagunas on January 8, 1770, where the priest, Nicolás Romero, declared that “knowing what I know about these mountains and its inhabitants, it is not at all difficult to imagine these deaths.” They reached Omaguas on January 30, and Peña was similarly convinced, although he thought it most likely that Isabel and the others left behind on the sandbar had been killed “by the Jibaros Indians.” He then commanded Joaquín to take the papers to officials in Quito in order to inform them of this “tragic happening.”

Joaquín reached the audiencia capital in early May, traveling back to Quito via the Napo River rather than retracing his steps up the Bobonaza. Among the papers he carried was a letter from Rocha and Bogé, which they had signed on December 16 in Andoas, stating that Isabel had promised that she would give him his “card of liberty” once they reached Loreto, where her father was waiting. Although her voyage had come to an awful end, Joaquín had done his part—should he not get the promised card? Joaquín spent three weeks trying to deliver the documents to the audiencia president, Joseph Diguja, but each time he came to Diguja’s office he was turned away, told by Diguja’s assistant that the president was too busy to see him. Then, as Diguja wrote, on May 28, Quito authorities came to him:

It became known that walking in this city was a fugitive Negro who had come from the province of Maynas. He was apprehended and put in jail. There they found in his possession papers and a letter that was for the head of this Audiencia, which give an account of the extraordinary happenings of the disappearance of the Gramesón family that was traveling by the Río Bobonaza in that province.

With Joaquín’s arrest, Spain’s colonial bureaucracy began to turn in its usual tortured way. Joaquín, Diguja concluded, was to be blamed for “having been the one that was conveying the said family.” This slave had even tried to “hide” the various reports “indispensable for verifying” what had happened, Diguja wrote, and yet he now had the nerve to ask for “his liberty.” The audiencia court quickly took up the matter, and it decided that Joaquín was not the only one who should be jailed. The court decided to send to Omaguas a warrant for the arrest of the two Frenchmen on the grounds that they had never obtained a permit for travel to the Maynas province.

The audiencia’s investigation continued for another three months. Joaquín was interrogated, and he confessed that as far as he knew, Isabel and her brothers had left Riobamba without proper travel papers. Although Jean Godin, in 1740, may have secured permission from the viceroy of New Granada authorizing him to travel this route, that permit, the court decided, hardly applied to Isabel and her family in 1769. “These roads,” wrote a Quito official, are “closed because of their being a route to the Portuguese colony.” The law did not “permit commerce or even communication” across this border, and anyone who traded “with a foreigner without a license” could “lose his life.” Because Joaquín was one of the “accomplices in this sinful behavior,” it was only right that he be imprisoned.

Even members of Isabel’s family in Riobamba were asked to explain themselves. Fearful of being fingered as “accomplices,” they did their best to wiggle out of any possible blame. Did Isabel and her brothers have a proper license for this travel? No, admitted Isabel’s brother-in-law, Antonio Zabala. However, Isabel had left “upon the orders of Jean Godin”—she was obeying her husband, as Peruvian law expected a woman to do. Nor was it conceivable, he and others swore, that Isabel planned to engage in any illicit trading. She had become very poor in the previous years, they said, and had departed with but a few personal things and a paltry “100 pesos.” The caravan of thirty-one Indian servants and countless mules was conveniently forgotten, and this seemed to mollify the stuffy bureaucrats.

At the end of August, the Quito court wrapped up matters by ordering villages and cities in the mountains of the audiencia—places that might serve as departure points to the Amazon—to post a public warning. Everyone was to understand that travel into the Amazon was prohibited without a permit and that anyone who traded with a “foreigner” there risked being put to death. One town after another—Ambato, Patate, Riobamba, and Baños—dutifully nailed up the warning, and the sudden appearance of this government advisory might have perplexed people had they not been quick to read between the lines. And thus did the news spread throughout the audiencia and to points beyond, as surely as if a town crier had stood in every village’s plaza mayor and bellowed out the headline.

Madame Godin, dead.

* Perhaps the best-known example of this phenomenon occurred in the winter of 1846, when the infamous Donner Party became trapped in the Rocky Mountains. More than two-thirds of the twenty-five men in the group died, mostly from starvation, while only four of fifteen women died, and they succumbed only at the very end of the ordeal.

* The reasoning here seems to be that if it had been daytime when they were attacked, they would have been wearing their undergarments. But since these items of clothing were found in the hut, the Indians concluded they must have been killed while in their sleep wear.