Examples of Compromise and Presence of Subversive Multivector Threats

Information in this chapter

• Black, White, and Gray: Motives and Agendas of Cyber Actors with Respect to Cybercrime and Espionage

Introduction

Thus far, we have discussed a multitude of ideas and concepts pertaining to subversive multivector threats (SMTs). We have discussed the origin of these threats on the global stage describing them in detail on the basis of their criminal and intelligence-driven activities. In doing so, we have explored examples of exploitation stemming from the ancient to the modern times, paying special attention to those that introduced the exploitation of purpose-built technology for criminal profit. We have examined the impact that regulatory acts and standards bodies have had in encouraging exploitation and compromise, while discouraging these activities often in the same breath. Furthermore, we have dealt deeply, marking a swift descent into the realm of state-sponsored intelligence types, criminal syndicates, as well as national and subnationally sponsored organizations. Additionally, we have introduced taxonomy and terminology that we believe accommodate and integrate subordinate terms in a meaningful way, while allowing for much growth and collaboration, that is, the SMT. In Chapter 9 we discussed the ways in which the industry refers to well-noted yet not so well-known (until very recently) cyber attacks known as advanced persistent threats (APTs). Our goal in Chapter 9 was to argue for and on behalf of a method for compartmentalizing APTs along with other terms such as advanced persistent adversaries (APAs) in our proposed taxonomy, the SMT.

We discussed what we believe to be the seven characteristics of SMTs, while attempting to introduce each of them succinctly and provide brief examples. Thus far, we have addressed examples from the intelligence community (IC), Department of Defense (DoD), defense industrial base (DIB), and energy communities, identifying similarities and differences among the cases presented, all with the intention of educating the reader on the topics being presented. Cybercrime and espionage are areas of study that the authors feel strongly demonstrate an evolution of agenda and opportunism. It is our belief that more notable organized criminal elements the world over have made the leap into the cyber realm recognizing the diversity of opportunities presented by it for more than a decade.1,2

Black, White, and Gray: Motives and Agendas of Cyber Actors with Respect to Cybercrime and Espionage

The infamous American bank robber, Willie Sutton, is believed to have said on being apprehended, after a long spree of bank robbing, that he robbed banks “because that’s where the money is.”3 Regardless of whether you believe this story about Mr. Sutton or not (he himself denied having said this later in life in his autobiography, although he did acknowledge that had he been asked he would have said that and much more!), it is important to note the underlying significance of the statement.

Why do criminals do what they do? It is because ultimately, whether it is robbing banks at gunpoint or undermining economies via subversive technological activity, there is money (or profits) to be made. Evidence of this abounds. For example in Russia, in 2009, Russians committed more than 17,500 acts of cybercrime, an increase of 25% from 2008 according to the Russian Interior Ministry.4,5,6

Ours is a real world. It is not for the faint of heart. It is not explicitly good, nor is it explicitly bad but rather an amalgamation, a world of shades of gray. This is true for all aspects of our world, including the dominion of information security and its practitioners. Within our world there are gray areas, and though there are smartly defined “black hats” and “white hats” there also exists a world that caters to both, the world of the “gray hat.” It is within this world that we find ourselves spending a great deal of time in study and analysis. Motives here tend to be ambiguous and, as a result, contribute to the challenges associated with attribution. This is a world that inspires many areas of study. Some of the subordinate aspects of study here include, but are not limited to the following:

There are myriad data sources, cases, legal arguments (national and international), geopolitical amendments, and law enforcement challenges associated with the gray areas that most people would prefer not to acknowledge. Whether white, black, or gray, these areas require advanced comprehension and understanding of tactics and techniques, in addition to the motivations and lengths to which cybercriminals and syndicates are willing to go in order to ensure their business interests remain profitable, consistent, and unfettered by security researchers, law enforcement, or national agencies. Additionally, the study of these activities requires dedication, strength, and watchfulness. The willingness to maintain the courage of one’s convictions in order to obtain and leverage the intelligence gathered for the greater good is paramount and, in reality, one of the most important traits that a researcher who elects to focus on this space and the subject matter we are discussing can have. Ours is an area of study that is focused on a fluid, intangible focal point; ever changing and dynamic; well-established, informed, and trained; and ready to act out singularly or in concert. It is not for the faint of heart or for the unprepared mind. This area of information security study (which of course is also part of the greater body of knowledge and research dedicated to criminology) deals with subject matter and activity such as the following:

• Extortion/protection rackets

• State sponsored/cyber terrorist/cyber mercenary activity

• ATM/credit card fraud (carding)

• Online gaming, gambling, racketeering

• Trafficking in criminal contraband/fencing of stolen property

• Counterfeiting of currency/legal tender

When taking into consideration the illicit cybercriminal activities described above, it should come as no surprise to anyone that there is a vast amount of money to be made. Recent estimates suggest that the cybercrime on a global scale is a 105 billion USD industry, far exceeding the revenues associated with the global drug trade.7,8 That profitability and economic superiority is the key motivator associated with this activity should come as no surprise in today’s world. Look around and ask yourself what is for sale? The answer is EVERYTHING!

• National security and residency numbers for non-U.S. nationals

• Banking account information and personal securities account information

Our assertion is that everything is for sale so long as there is someone willing to buy. That said, it should come as no surprise (as mentioned earlier), that criminals (professional and semiprofessionals) have recognized this and are working diligently to provide goods to the marketplaces they service. Why you ask? In short because successful professional criminals tend to be visionary equal opportunists with respect to recognizing opportunities to profit while controlling the amount of risk they incur. Cybercriminals—those who are organized and approach their craft and trade like any other business person—embody the same entrepreneurial spirit that you and I might, were we to start our own businesses. Though it is often hinted at, it is very rarely described in a manner that truly portrays the level of sophistication that is involved (not solely technical sophistication, but managerial and operational as well). This is a powerful statement. We believe the tenacity demonstrated by these organizations and actors, in addition to the agility they reveal during the course of their activity, warrants a discussion of a different sort. These organizations operate in a manner that is often quite visionary (with respect to their ability to recognize new revenue generating opportunities and execute strategies to capitalize off of them).

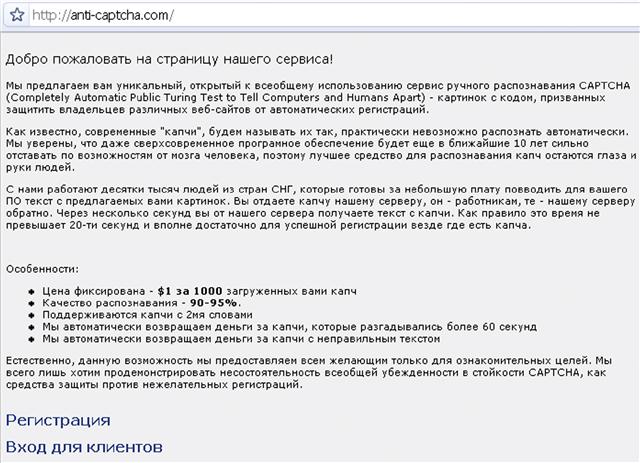

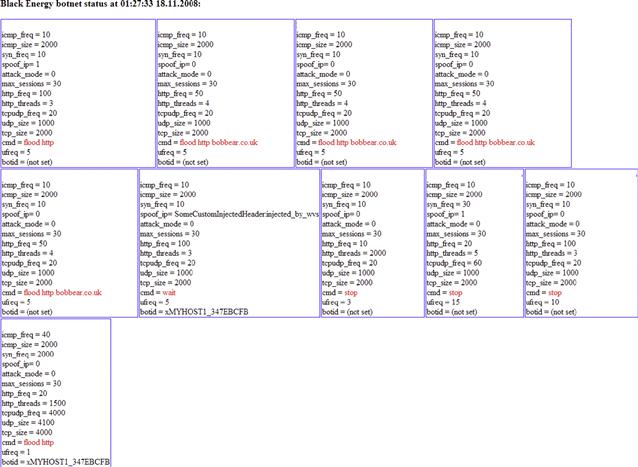

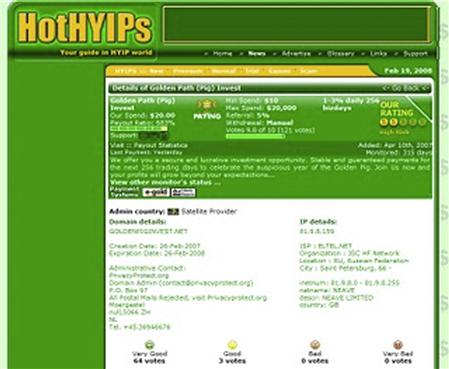

They are typically not concerned who they victimize, or with whom they conduct transactions, nor do they concern themselves with what their consumers do with the information or goods they provide. A dollar is a dollar to these organizations and the consumer is, well just that, a consumer. There is no sense of obligation or ownership regarding the wares or services (though there are standards and in many cases quality guarantees that endorse products and services provided by many in the underground) being sought after and secured for nefarious means (Figures 10.1–10.6).

Figure 10.1 Example of a Russian malicious code, content, and services site that offers guarantees.

Figure 10.2 Statistics associated with the Black Energy Botnet, a Botnet with service guarantees.

Figure 10.3 PHP denial of service tool.

Figure 10.4 Low orbit ion cannon denial of service tool.

Figure 10.5 Example of malware rated sites.

Figure 10.6 Example of onion routed message traffic layered encryption.

As this area of study gains momentum and popularity, it becomes more evident that the more we learn and apply in our studies the more there is to know and share with enterprises and security practitioners the world over.

Gaining an understanding of these organizations and trends, in addition to how they operate economically, is critical in combating them. Defining the economic ecosystems that exist and have supported many (not all) instances of SMTs is critical. Economics is the study of the production, distribution, and consumptions of goods and services. If you investigate the etymology of the word, you will discover that the English word “economics” comes from the ancient Greek word oikonmia, which means “management of a household or administration.” Economists strive to explain how economies work, what influences them, and what agents are present within these economies that influence change while interacting with one another, by drawing distinctions in the management and administration of markets, goods, services, and commodities sold and requested, and at given rates.

Often, economists will spend a great deal of time describing the differences which exist in regard to the scope of economics (e.g., positive and normative economics), the differences between the theoretical and practical, or applied economics as they pertain to mainstream economics while taking into consideration the relevance of heterodox economic theories in course. For the most part however, economists will separate and segregate economic discussions into contextual terms, thereby grouping them in either microeconomic or macroeconomic categories; little and big for the lay economist. In doing so, economists are free to address issues such as inflation, unemployment, and monetary and/or monetary fiscal policy as they pertain to an economy in its entirety. As we have discussed, many factors influence the development of an economic ecosystem. It is no coincidence that the laws and principles that govern economics as a discipline find themselves applicable to all market systems; they are universal and must be understood in order to determine the motives of both suppliers and consumers. Our industry is no different from any other. These laws are applicable to those aspects of our world and the markets that are served, both seen and unseen. As such, it is critical that we, as information security professionals tasked with the responsibility of safeguarding and protecting our nations, corporations, and personal interests (as well as the personal interests of those who cannot protect themselves), are fluent and comfortable in our understanding and knowledge of these economic truths.

In the next installment of this series, we will delve deeper into that which has influenced the evolution and emergence of new, and largely unseen markets focused on addressing the market demands of cybercriminals by cybercriminals throughout cyberspace.

One of the goals of this book is to aid information security professionals and law enforcement in securing those who they have been charged with shepherding. We believe that these points underscore the importance of this study and the need to revisit it in a manner not previously seen clearly:

• Cybercrime transcends borders and national boundaries and often (not always) does not discriminate.

• It is truly a global problem with global implications as there are individuals, gangs, cohorts, syndicates, organized crime elements, terrorists, and state-sponsored entities actively participating and supporting the economies that support these criminals.

• Cybercrime represents a real threat to the U.S. economy and economies of nations the world over.

• Cybercrime represents a threat to the security interests of the United States of America and nations the world over (see first bullet).

• It impacts governments, businesses, and the private lives of law-abiding citizens the world over, most of whom are unaware that activity of this nature, and to this degree of maturity, is taking place, and that they might be unwittingly made a part of it via system and other forms of exploitation.

• It often directly impacts those who cannot protect themselves.

• Its impact, prevalence, and maturity are underestimated and as a result often negated.

With respect to these points and the others presented in this book, we have one question to pose before moving forward: In the twenty-first century, what has the potential to do more harm—bombs, bullets, or bits? It is our assertion that in almost every way, bits can, and will, prove to be a threat, in practice as effective as, or more effective than, bombs and bullets. As we investigate the following examples of SMTs, we examine specific cases, philosophy, and techniques in use.

Onion Routed and Anonymous Networks

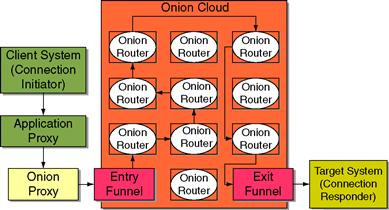

Though we have mentioned onion routing (OR) previously, within the context of this chapter we feel it appropriate to do so again in slightly greater detail. Many of the cases described and discussed within this chapter leveraged in some capacity onion-routed technologies in order to ensure that communications and extraction of data remained largely untraceable, making attribution difficult, if not impossible. OR is a mature networking concept and technological reality (Figure 10.7).

Figure 10.7 Example of onion routed network traffic flow.

It should be noted that onion routers and OR are different than The Onion Router (TOR) project. The OR originally began as work funded by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) in 1995.9 It initially focused on four key goals10:

This earliest generation of the concept of OR saw many ideas being brought forth with some being disregarded and others sidelined until later generations of OR technology were ready to accommodate them, such as the idea that all ideas were effectively one hop away from one another. In the Spring of 1996, we saw the introduction of mixing and real-time mixing to the network. Other ideas introduced yet not included until later generations of the technology included the use of Diffie-Hellmann (DH) keys as opposed to sending the onion key itself as part of the exchange. In doing so, the idea of perfect forward secrecy would be realized provided the DH keys and onion keys (now combined) were rotated on a frequent basis. Later that same year, other notable ideas were introduced to the project, including in an academic paper,11 although these too would not be seen until the second generation of the project. These ideas included the following:

• Proof of concept with 5 node system running on a single machine at Naval Research Laboratories (NRL) with proxies for Web browsing, with and without sanitization of the application protocol data on a Solaris 2.5.1/2.6 operating system architecture

Work began on the first generation of the source code and included the removal of cryptographic technology from the main code body in order to comply with cryptographic export restrictions. Generation 0 code became generation 1 code in the May of 1996 and was released for public use in July of 1996.

The year 1997 saw more funding from the ONR in addition to funding by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under its High Confidence Networks Program. During this time, research was conducted that saw design considerations for the ability to obfuscate cellular (mobile) communications, location badges, and other location-tracked devices in addition to ensuring that the data contained within these devices remained secure. The project published a paper at the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy in San Diego12,13 that described the following:

• Separation of proxy from a router

• Separate cryptographic modules designed to run on separate machines or specialized hardware

In 1998, several generations of 0 and 1 onion routed environments were implemented and operational. A distributed network of 13 nodes existed at NRL, Naval Research and Development (NRAD now SPAWAR), and the University of Maryland (UMD). At this time, the NRAD redirector was built in a manner that included the following:

In 1999, the project received an award for a paper written by the team on “Anonymous Connections and Onion Routing”14 while it was also seen that members of the core team left the NRL to pursue other endeavors. Research and analysis work continued in spite of these challenges. In January 2000, the project decommissioned the generation 0 proof of concept network. During its two years of operations, the project received over 20 million requests from more than 60 countries and all major United States top level domains (TLD) were processed by the initial prototype. The significance of this is both compelling and noteworthy in that it demonstrated a fundamental desire for the safeguards and privacy provided by the project to those who elected to use its technology. Perhaps even more compelling is that during that same year at the first Privacy Enhancing Technologies Workshop, a paper15 was presented which would see the idea for TOR Network come to pass as Paul Syverson meets Roger Dingledine16 for the first time. In 2001, work resumed on the OR project once again funded by the DARPA, this time under the Fault Tolerant Networks Program. The goal of this reinvigorated research push was to make the generation 1 version of the projects code complete enough to run a beta network while also allowing for fault tolerance and resource management. The team also received the Edison Invention Award for the invention of OR. Additionally, the team received a patent for its technology awarded by the United States Patent office.17 The year 2002 saw the beginning of work on generation 2 (TOR), based off of code that was originally written by Matej Pfajfar at Cambridge University. That code has now been removed entirely from the codebase. During this period, Privoxy, a filtering proxy, was adopted and included in the codebase. In 2003, the project received another round of funding from the ONR for generation 2 development and deployment research, the DARPA for designing resource management and fault tolerance, and the NRL for the development of survivable hidden servers. October 2003 marked an important milestone in the project’s overall growth and development as the TOR network was launched along with the code being released under the free and open MIT license. Toward the end of the year, the project had approximately a dozen volunteer nodes, most of which were located in the United States of America while one was located in Germany.

This would not remain the case for long, as the world would soon see. In 2004, location hidden servers were deployed along with the hidden wiki. A paper, written describing the design of TOR, was published at USENIX Security,18 and that marked the end of funding from the ONR and the DARPA, although internal NRL funding continued for work being conducted on location hidden servers. The year 2004 also saw the advent of nonpublic sector investment in the project coming from the Electronic Freedom Foundation (EFF) for continued TOR deployment. By year’s end there were approximately 100 TOR nodes on three different continents. May 2005 saw conservative estimates of approximately 160 TOR nodes on five continents while in 2007 conservative estimates saw that number swelled in excess of 10,000 TOR nodes on five continents. The project has, as of 2007, ceased tracking the nodes because of the difficulty (even for themselves), in doing so. It is important to note that the authors of this book do not believe that onion routed networks—TOR or others—are, in and of themselves, insidious, as their creation was to solve and address very real issues faced by military and IC actors. We do however feel that responsible use and disclosure are problematic with respect to these networks, their software clients, and their clientele when due diligence and care are not taken in exploring and supporting their use. Operating blindly with respect to the potential perils of use associated with them can have ghastly results.

Even worse, operating in alignment with what are considered the normal and agreed to parameters governed by the end user licensing agreement (EULA) can still result in awkward, if not frightening, ends. In 2007, Swedish security consultant Dan Egerstad found this out when he was arrested by Swedish authorities for illegal possession of information gained via illicit means, and belonging to foreign embassies, NGOs, and others. Egerstad faced serious charges and in the end made the decision to not only delete but destroy the hard drives he used to monitor and analyze traffic gathered from other projects: “I deleted everything I had because the information I had was belonging to so many countries that no single person should have this information, so I actually deleted it and the hard drives are long gone.”19,20

WikiLeaks

Although TOR was not designed to act as a tool for whistle blowing or the trafficking of illicitly obtained materials, its architecture and thoughtful design considerations with respect to privacy and the obfuscation of sources made it an ideal complimentary technology for this work. WikiLeaks first appeared in public on the Internet in January 2007, and was founded, according to information contained on the “About” page of its site by “…Chinese dissidents, journalists, mathematicians and start-up company technologists from the United States, Taiwan, Europe, Australia, and South Africa.” This assembly of founders, contributors, and proselytizers is most notably represented by Julian Assange, an Australian born, former hacker who had been arrested by the Australian Federal Police in 1991 for having accessed computer systems and networks belonging to an Australian university, Nortel Networks, and other organizations. In 1992, he pleaded guilty to 24 charges of hacking and was released on bond for good behavior.21 Later, Mr. Assange embarked on a career in computer programming, which eventually saw him become involved with the team at WikiLeaks. Mr. Assange describes himself as being a member of WikiLeaks’ advisory board although some reports cite him as being the site’s principal founding member and primary visionary. The primary mission of WikiLeaks, in its own words, is to expose oppressive regimes in Asia, the former Soviet bloc, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East in addition to other areas of the world in which people desire to reveal what the founders consider to be “unethical” behavior exhibited by their governments and corporations.22,23 In 2007, the site stated that it had over 1.2 million documents that it was preparing to publish, all of which were sensitive and had not been made public prior to the site coming into being. Additionally, one or more WikiLeaks activists were in possession of hosts and servers acting as nodes for the TOR network. According to sources, millions upon millions of secret transmissions, taking advantage of the technological sophistication and privacy afforded by TOR, were being initiated by hackers in China in order to gain intelligence regarding foreign government’s information.24 Members of the group and its nine member advisory council, on which Mr. Assange sits in a leadership role, later refuted these claims. Although the group still maintains that one of its primary goals is to ensure that journalists are not imprisoned for disseminating sensitive or classified documents such as the case has been in certain parts of the world, most notably as in cases such as those of Shi Tao, a Chinese journalist who violated the People’s Republic of China’s request to not publish anything having to do with the events of June 4, 1989, the anniversary of Tiananmen Square, as it was thought that many predemocratic Chinese may come back to the Chinese mainland on the anniversary of the event and engage in activity that threatened the politico-social order’s stability. Shi Tao was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2005 for having publicized an email that outlined this request via his private yahoo.com account. WikiLeaks has acted as a relatively indiscriminate outlet for what its advisors and contributors believe to be ethically unsound. It is unclear to what degree or level the organization actually scrutinizes the data it receives or the potential ramifications for leaking such data. It is, with respect to this, that the authors feel WikiLeaks has become a participant, willing or otherwise, in many instances of cybercrime and espionage, and continues to play a role as a source involved in many SMTs. Take, for example, the case of United States Army Spc. Bradley Manning. It should be noted that the authors of this book do not and are not advocating in favor of or against WikiLeaks but rather are concerned with the application of sound thought and reasoning regarding the disclosure of sensitive data.

Project Aurora

On January 14, 2010, McAfee Labs identified a zero-day vulnerability in Microsoft Internet Explorer that was used as an entry point for Operation Aurora to exploit Google and at least 20 other companies. Microsoft issued a security bulletin and patch, and the world waited with baited breath to see if this would address, and subsequently mitigate, the threat presented by this vulnerability. Operation Aurora was a key example of a well-coordinated attack. The attack itself leveraged code (there are now several iterative exploits based off the original), which exploited certain aspects of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer Web Browser. Through this exploit, an attacker could gain access to computer systems susceptible to the vulnerability. Upon compromising a vulnerable host or system, a download is initiated which subsequently activates the malicious code and content within the systems. The attack itself was initiated furtively. When targeted users accessed a compromised Web site, they were redirected to remote servers and promptly infected. In the case of Operation Aurora, the connections created were used to extricate intellectual property, data, and user accounts belonging to Google, Inc. Dmitri Alperovitch, Vice President of Threat Research for McAfee said this about the information security giant, “We have never ever, outside of the defense industry, seen commercial industrial companies come under that level of sophisticated attack, it is totally changing the threat model.” Mr. Alperovitch was correct. Operation Aurora did change the threat model in the industry and offered a significant wake-up call to all who had ears to hear it, regarding the realities of the evolution of the threat landscape.

Summary

In this chapter, we explored examples of SMTs that you, the reader, may or may not have been familiar with previously although are now aware of.

We explored the motivation of criminal activity seen globally. Many of these activities are now either indirectly or directly influenced by cyber technology and will continue to be going forward. We saw the myriad criminal areas that have previously been overlooked by information technology and information security professionals although now they are impossible to be ignored. Our journey in Chapter 10 saw us explore the impact of the motivation of criminals and criminal organizations such as globalization and opportunity for profit. We examined examples of technology supported and used in the execution of these events, and specifically explored onion routed networks, the TOR project, and WikiLeaks. Additionally, we reviewed the case of Spc. Bradley Manning, currently being held by the United States Army and DoD on charges related to the illegal obtainment and dissemination of sensitive and classified information, and how he transformed himself into an SMT.

1 www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=191389

2 www.bloomberg.com/news/2010–10–05/russian-cybercrime-thrives-as-soviet-era-schools-spawn-world-s-top-hackers.html

3 www.fbi.gov/about-us/history/famous-cases/willie-sutton/willie-sutton/

5 http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=ru&u=http://www.mvd.ru/news/&ei=agmzTIHpHMS8nAfM_Ij0BQ&sa=X&oi=translate&ct=result&resnum=1&sqi=2&ved=0CCEQ7gEwAA&prev=/search%3Fq%3Dhttp://www.mvd.ru/news/%26hl%3Den%26prmd%3Div

6 www.bloomberg.com/news/2010–10–05/russian-cybercrime-thrives-as-soviet-era-schools-spawn-world-s-top-hackers.html

7 www.itu.int/ITU-D/cyb/cybersecurity/docs/itu-understanding-cybercrime-guide.pdf cyber-crime on a global scale is a 105 billion USD.

8 www.itu.int/ITU-D/cyb/cybersecurity/projects/cyberlaw.html

9 www.onion-router.net/History.html

10 www.onion-router.net/Publications.html#old-slides. Original (old) onion routing briefing slides. The slides describe onion routing and uses of onion routing in 1996.

11 Anderson, R. (Ed.), 1996. Hiding routing information. Information Hiding. Springer-Verlag. pp. 137–150.

12 Proxies for anonymous routing. Proceedings of the 12th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, IEEE CS Press, San Diego, December 1996, pp. 95–104.

13 www.onion-router.net/Archives/TNG.html provides a high level overview of these features.

14 Anonymous connections and onion routing. Proceedings of the 18th Annual Symposium on Security and Privacy, IEEE CS Press, Oakland, May 1997, pp. 44–54.

15 Towards an analysis of onion routing security. Workshop on Design Issues in Anonymity and Unobservability, Berkeley, July 2000.

16 Official title of the first workshop was Design Issues in Anonymity and Unobservability and the proceedings was titled Designing Privacy Enhancing Technologies.

17 Onion routing network for securely moving data through communication networks United States Patent 6266704.

18 TOR: The second-generation onion router. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Security Symposium, August 2004.

19 www.smh.com.au/news/security/the-hack-of-the-year/2007/11/12/1194766589522.html?page=fullpage#contentSwap1

20 www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2007/11/dan_egerstad_ar.html

21 www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/06/07/100607fa_fact_khatchadourian?currentPage=all

22 www.wikileaks.org/wiki/Wikileaks: About

23 www.asiamedia.ucla.edu/article-eastasia.asp?parentid=60857

24 www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/06/07/100607fa_fact_khatchadourian?printable=true