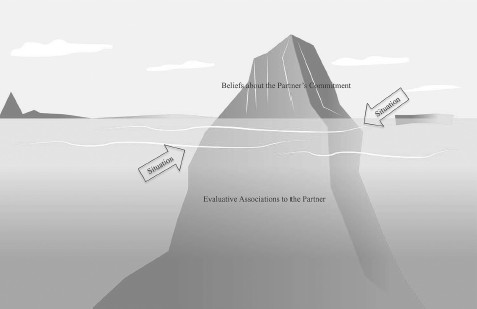

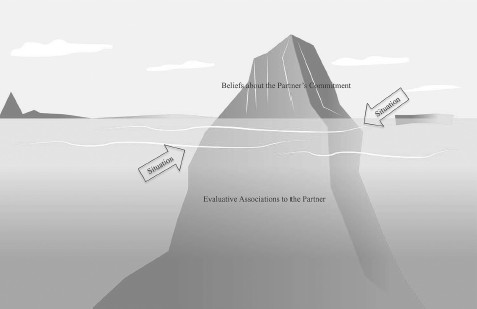

FIGURE 3.1 The Iceberg Model of Trust

p.35

As Katy and Todd sat across from one another at that coffee shop table, they both had a lot to think about. On first meeting, Katy noticed that Todd was heavier than his (apparently none too recent) Tinder picture and Todd noticed Katy’s deep blue eyes and what seemed like self-deprecating wit. Katy wondered whether she was speaking too much or too loudly and Todd wondered whether he was leaving too little time to get across town on time for his bar exam prep class. They also shared one vexing obsession – trying to figure out what the other was thinking. When Katy noticed Todd checking his watch, she couldn’t help but wonder whether he was laughing at her jokes just to be polite. Todd couldn’t escape his self-conscious preoccupation that Katy was staring disapprovingly at his midriff. Hoping for the best, but feeling anxious and unsettled, they both wanted to feel safe in the knowledge that hurt and rejection were unlikely.

The reason why Katy and Todd felt so vulnerable to rejection at first meeting comes up time again in interdependent relationships: Partners cannot read each other’s minds (Griffin & Ross, 1991). That’s why, months later, Katy is now experiencing such trepidation at the thought of asking Todd to take a weekend away to meet her parents. She has no way to know the precise priority he will put on her needs as opposed to studying for his bar exam (Murray & Holmes, 2011). If she could read his mind, her vulnerability would disappear because knowledge of his goal priorities would tell her exactly what to do to be safe (i.e., ask him to go vs. keep silent).

In this chapter, we argue that the experience of safety functions as an embodied goal because its control over perception and inference gives people the power to believe they actually are reading their partner’s mind. Moving closer to the goal of being safe makes Katy believe that Todd depends on her and will not hurt her if she depends on him, whereas moving further away sends a warning that rejection might be imminent. The pursuit of safety disambiguates risky and unfamiliar situations by making the unknowable contents of a partner’s mind manifest.

p.36

What marks progress toward the goal of being safe from being hurt? Which specific affective sensations, physical perceptions, situational assessments, and reasoned beliefs signal progress toward this goal and which thwart it? Is satisfying the goal to be safe a more preoccupying concern in some situations than others? Is it a more preoccupying concern for some people than others? How do people restore safety when ongoing events threaten progress toward this goal? This chapter tackles such questions as we explore in depth how the goal to be safe from being hurt and let down by the partner infuses attention, inference, and behavior.

In the first section of the chapter, we introduce the desired end-state: To be safe and protected from the potential for physical or psychological harm by a partner. We argue that safety comes from partners’ equal and mutual dependence on the relationship. We then describe how progress toward mutual dependence, and thus safety, is signaled through mental representations and bodily states associated with the experience of trust in the partner. In describing how trust signals safety, we advance three interrelated arguments.

One. Trust is not equivalent to safety. Being more trusting does not necessarily move people closer to the goal of being safe and being less trusting does not necessarily move people further away. In making this point, we hope to set the imprecision in our past writing on this topic right. Attachment and interdependence theorists (like us) usually equate trust and safety by defining trust as a state of felt security in the partner’s presence (Holmes & Rempel, 1989; Murray, Holmes, & Collins, 2006; Simpson, 2007). Feeling more trusting involves the secure and comforting anticipation of good things to come through dependence on the partner, whereas feeling less trusting involves the anticipation of bad things to come (Deutsch, 1973). However, feeling safe is not the same as being safe. Todd may feel quite safe and secure in situations where Katy is actually highly likely to hurt him and Katy may feel quite unsafe and insecure in situations where Todd is actually highly unlikely to hurt her. As we will see, trust provides a means for Katy to gauge how she might best make herself physically and psychologically safe from harm, but being more trusting itself does not guarantee progress toward the goal of actually being safe.

Two. Trust involves more than people typically think it does. The term “trust” usually invokes beliefs that can be readily articulated (e.g., “I don’t know if she really cares about me” or “I don’t think I can trust him to do what is best for us”). Such reasoned beliefs capture a crucial part of trust (Holmes & Rempel, 1989), but they do not tell the whole story. We will argue that the automatic affective or evaluative associations and bodily movements that merely thinking of the partner provokes are also crucial to the experience of trust.

Three. Trust varies more than people think. The term “trust” usually refers to a chronic state denoting a perceiver who is more or less trusting across situations. We will use this individual difference sense of the term when we describe how automatic evaluative associations and deliberative beliefs provide bases for trust. However, we also maintain that trust is as much a reactive and dynamic sentiment as it is static. It must vary from one situation to the next to sensitively signal progress toward the goal of being safe from the potential for hurt. This dynamic property to trust means that becoming less trusting in a given situation or relationship context can actually move people closer to the goal of being safe from the potential for harm. Although this assertion might seem paradoxical, it is central to our contextual take on motivated cognition. Think of Katy’s predicament. She wants Todd to spend the weekend meeting her parents, but as devoted as he is to her, this weekend he is actually more devoted to his need to study for his bar exam. Given Todd’s strong incentive to disappoint her, Katy can better keep herself safe from harm by being more hesitant to trust and depend on Todd than usual.

p.37

In the second section of the chapter, we describe exactly how people satisfy the goal to be safe. That is, we focus on the means of goal pursuit. We detail how the goal to be safe from hurt and rejection at the partner’s hands biases perception and inference in situations that create inequality in dependence (Overall & Sibley, 2008, 2009a). We argue that people have two basic means for restoring safety in such situations: Increasing their partner’s dependence on them and decreasing their own dependence on their partner. As we will see, the specific motivational machinations needed to restore safety depend on the (1) specific situation and (2) overall progress in pursuit of the goal to be safe as signaled by trust. Katy feeling vulnerable because she feels inferior to Todd elicits different tactics for restoring mutual dependence than feeling vulnerable because he has been intentionally hurtful. Further, people who are more chronically trusting restore safety in different ways than people who are less trusting (Murray et al., 2011). Such flexibility in goal pursuit echoes a point raised in the last chapter. Goal pursuit depends on situational affordances (Cesario, Plaks, Hagiwara, Navarrete, & Higgins, 2010). Consequently, fighting to preserve trust is a more viable means of restoring safety in some situations and for some people than others.

We conclude the chapter by explaining when being safe from harm is a more preoccupying goal. We highlight the role that relationship transitions, difficult partners, and personal dispositions play in making the pursuit of safety goals a more (or less) chronic preoccupation, a topic we take up again in later chapters.

The Desired End-State: Safety

What does it actually mean to be safe from the potential to be hurt by a partner? Katy could keep herself safe from being hurt by Todd by never venturing into that coffee shop for a first date – but taking such extreme protective measures would also forgo the possibility of the relationship even existing. To satisfy fundamental needs to belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), and to reap the rewards gained from interdependence (Murray & Holmes, 2011), people need to risk some level of dependence on a partner. However, risking such dependence invites the possibility of being hurt and rejected by a partner (Murray et al., 2006).

p.38

Interdependence theorists believe that the “principle of least interest” holds the key to safety (Drigotas, Rusbult, & Verette, 1999; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959; Waller, 1938; Wieselquist, Rusbult, Foster, & Agnew, 1999). Succinctly stated, this principle is: Whoever needs a relationship the least, holds the most power within it. If Katy is completely enamored with Todd, but Todd could take or leave Katy, Todd holds the power in the relationship. In such an unequal relationship, Katy would have no choice but to cater to Todd’s needs in order to keep him, but Todd would have little incentive to take care of Katy’s needs when it costs him. He simply would not have anything to lose by being selfish and uncaring. Indeed, in relationships where one partner is markedly less committed than the other, the less committed or “weak link” partner is more likely to behave in rejecting and hostile ways in conflict situations (Orina et al., 2011). To keep safe from being hurt, Katy needs to avoid being caught in such a position of vulnerability. She can do this by ensuring that Todd generally needs her at least as much as she needs him. That is, she needs to ensure they have equal interests in the relationship. In an equal relationship, Katy and Todd both stand to lose the other’s good will by being uncaring. Therefore, both have strong incentive to take care of the other’s needs. Equal and mutual dependence essentially keeps them both safe from being hurt.

To best satisfy the goal of being safe from harm, Katy should track Todd’s dependence on her as she navigates situations within her relationship and use his dependence to decide how much dependence she should risk herself. That is, she should only allow herself to depend on Todd in a given situation when she knows he is motivated to be caring because he needs her. The problem is that Todd’s commitment to Katy controls his dependence on her (Drigotas & Rusbult, 1992) and Katy does not have unfettered access to the contents of Todd’s consciousness. She cannot know exactly how committed he is at any point in time. The best Katy can do to satisfy the goal to be safe and protected against harm is guess at the contents of Todd’s consciousness. Katy’s uses her trust in Todd to measure just that (Murray et al., 2006).

Trust: Marking the Best Means of Goal Pursuit

The experience of trust marks progress toward the goal of being safe because trust provides a means for mindreading a partner’s likely dependence and motivations in a given situation (Deutsch, 1973; Holmes & Rempel, 1989; Murray et al., 2006; Simpson, 2007). Figure 3.1 depicts the conceptual model of trust that underlies our thinking.

p.39

FIGURE 3.1 The Iceberg Model of Trust

This model conceptualizes trust as a metaphoric iceberg because trust has two main characteristics in common with icebergs. Both are deceptive in appearance. Just as the tip of an iceberg conceals its mass and depth beneath the ocean waves, trust captures considerably more than the beliefs that come to the tip of a person’s tongue. Both are also dynamic in impact. Just as toppling an iceberg can trigger climatic changes, including tsunamis (!), threatening or upending trust can also create profound changes in the partners’ interaction patterns.

Figure 3.1 uses these points of similarity to illustrate how Katy’s sense of trust in Todd’s availability and responsiveness dynamically shifts with three markers of his dependence. In this figure, the visible “tip” of trust corresponds to readily articulated beliefs about the partner’s commitment (Holmes & Rempel, 1989). The invisible “undercurrent” of trust corresponds to automatic evaluative attitudes toward the partner (Murray et al., 2011; Murray, Gomillion, Holmes, Harris, & Lamarche, 2013). The “portability” of trust corresponds to changes in situation risk that alter the threshold for what it takes to be safe in ways that can make the goal to restore safety more or less acutely pressing (Overall & Sibley, 2008, 2009a). Just as much of an iceberg’s power lies beneath the surface, this model conceptualizes automatic partner attitudes as having disproportionate power over trust because these attitudes are especially diagnostic of the partner’s actual trustworthiness, activated without awareness in most trust-relevant situations, and require both motivation and cognitive resources to overrule (Murray et al., 2011).1 We go into more detail about each of these three markers of partner dependence and trust next.

p.40

Below the Surface: Automatic Evaluative Associations to the Partner

For the experience of trust to accurately diagnose the partner’s dependence, it should be sensitive to the overall quality of such past experiences with the partner (Holmes & Rempel, 1989). Safer, more dependent and committed partners behave differently than riskier, less dependent and committed partners. More dependent and committed partners are more likely to forgive transgressions, make sacrifices, and provide instrumental and emotional support (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Therefore, receiving a partner’s support, sacrifices, and forgiveness should signal equality of dependence and move people closer to the goal of being objectively safe. Conversely, being targeted by a partner’s selfish and rejecting behavior should signal inequality of dependence and move people farther from the goal of being objectively safe.

Close relationships scholars have always assumed that explicit reports of trust adequately track such diagnostic behavioral experiences (Holmes & Rempel, 1989). But there is now evidence to suggest that automatic or unconscious attitudes toward the partner might track such diagnostic behavioral experiences much more faithfully (McNulty, Olson, Meltzer, & Shaffer, 2013). The idea that people can know things implicitly that they cannot explicitly articulate is central to social psychology (Zajonc, 1980). In a classic study on introspection, Wilson and Schooler (1991) asked participants to taste-test jams and identify their favorites. Participants in the “reasons” condition first listed the reasons why they liked and disliked each jam before they rated their preferences for each jam. Participants in the “intuition” condition went with their gut and rated the jams without thinking about it. The experimenters then compared the ratings of the participant jam tasters to the ratings of expert jam tasters. The participants who went with their gut chose the jams favored by the expert jam tasters. However, participants who explained why they liked each jam made suboptimal choices that diverged from the expert jam tasters.

So what do the results of this taste-test study have to do with trust? They suggest that people can reason themselves right out of knowing who is safe to approach and who is best avoided. Research on the detection of deception makes this point dramatically. People do no better than chance when they rely on conscious thoughts to discriminate liars from truth tellers. However, people’s automatic associations to liars are more negative than their automatic associations to truth tellers (Brinke, Stimson, & Carney, 2014). Just as people intuitively know which jams are best, they also seem to intuitively know the truth when they see and hear it.

Given the diagnostic superiority of intuition over reason (at least for jams and lies), we reasoned that people probably also know more about their partner’s trustworthiness than they can reliably profess. Indeed, attitude theorists believe that people implicitly learn whether specific objects are good or bad through experience interacting with the attitude object (Fazio, 1986; Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006; Gregg, Seibt, & Banaji, 2006; Olson & Fazio, 2008; Wilson, Lindsey, & Schooler, 2000). Consequently, interacting with a more dependent (and reliably responsive) partner should condition more positive automatic evaluative associations to the partner than interacting with a less dependent (and reliably responsive partner).

p.41

We first tested the hypothesis that automatic partner attitudes capture past behavioral experiences with the partner in a longitudinal study of newlywed couples (Murray, Holmes, & Pinkus, 2010). In this study, each partner completed daily interaction diaries for 14 days within six months of marriage. These daily reports allowed us to assess how much caring and responsive behavior the partner engaged in on a daily basis (e.g., “My partner listened to and comforted me”; “My partner was physically affectionate toward me”) and rejecting and non-responsive (e.g., “My partner criticized or insulted me”; “My partner put his/her tastes ahead of mine”; “My partner did something I did not want him/her to do”). Four years later we then measured automatic attitudes toward the partner using the Implicit Association Test (IAT) (Zayas & Shoda, 2005).2

People’s automatic attitudes toward their partner uniquely diagnosed the prior likelihood of a partner being rejecting and non-responsive! When people perceived their partner as engaging in more non-responsive behavior in the initial months of marriage, they evidenced less positive (or more negative) automatic associations to their partner on the IAT four years later. The time span of this effect might seem inexplicable. Pavlov’s dogs could never have learned to salivate at the sound of a bell if dinner arrived four years after the bell. We doubt that the behaviors we picked up early on in these marriages were the very behaviors that predicted automatic partner attitudes four years later. It’s much more likely that similarly non-responsive behaviors recurred over the next four years and this ongoing pattern of behavior conditioned later automatic partner attitudes. Incidentally, the partner’s non-responsive behavior early in marriage did not predict later explicit evaluations of the partner, which suggests that automatic partner attitudes do indeed pick up on things explicit attitudes miss (McNulty et al., 2013).

People can more readily distort and deny unpleasant realities when they have executive resources available to support motivated reinterpretations of the evidence (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006; Olson & Fazio, 2008). For instance, high self-esteem people can better fend off threats to self-esteem when their executive resources are intact than depleted (Cavallo, Holmes, Fitzsimons, Murray, & Wood, 2012). If taxing executive resources also makes it harder to distort a partner’s behavior, automatic partner attitudes should be especially diagnostic of past experience with the partner for people who chronically experience diminished executive resources. People with chronically impaired executive resources should be more likely to take their partner’s behavior at face value than creatively distort and deny such behavior. Consequently, their automatic attitudes should be especially diagnostic of their partner’s trustworthiness, conditioned by largely unvarnished perceptions of their partner’s behavior.

p.42

We tested this hypothesis in a community sample of married couples (Murray et al., 2013). Each participant first completed the IAT (described above) to index automatic partner attitudes. We also assessed individual differences in cognitive resources through working-memory capacity (Hofmann, Gschwendner, Friese, Wiers, & Schmitt, 2008, p. 966). Working-memory capacity is the capacity to allocate control and attention in ways that effectively manage incoming demands and inhibit unwanted thoughts and impulses. Greater working memory makes it easier for people to creatively distort a partner’s behavior (Cavallo et al., 2012).

Each participant then completed 14 days of daily diary assessments to index how much caring and responsive and rejecting and non-responsive behavior their partner engaged in each day. At the end of the diary period, each participant again completed the IAT to index automatic partner attitudes. This study design allowed us to predict changes in automatic partner attitudes from partner behavior in the preceding two weeks. For people who were low in working-memory capacity (e.g., low in cognitive resources), the partner’s behavior conditioned changes in automatic partner attitudes. Those who identified more responsive (and less non-responsive) partner behavior later evidenced more positive automatic affective associations to their partner than those who perceived more non-responsive (and less responsive) partner behavior. However, the partner’s behavior did not condition later automatic attitudes for people who were high in working-memory capacity. In reflecting on the meaning of their partner’s behavior, these people were presumably more likely to selectively interpret, construe, and distort in ways that made their perceptions a less than perfectly reliable barometer of their partner’s actual behavior. As we noted earlier with the jam study, people can reason themselves right out of knowing what is good and safe to approach or bad and best to be avoided; when it comes to automatic partner attitudes, people high in working-memory capacity appeared to do just that.

Truly a Marker of Trust?

Although the longitudinal studies suggest that immediate evaluative associations to the partner accurately gauge the safety of interacting with the partner, they fall short of demonstrating that these attitudes instill trust in a partner. To make this point, we subliminally conditioned automatic attitudes toward the partner and then measured trust (Murray et al., 2011). In the first experiment, we conditioned more positive automatic attitudes toward the partner by subliminally pairing the partner’s name with positive words, like warm, sweet, attractive, strong, and funny. We conditioned more neutral automatic attitudes toward the partner by subliminally pairing the partner’s name with neutral words, like bike. In the second experiment, we added a further control condition where we subliminally paired an X with positive words (e.g., warm, sweet, etc.). This latter condition allowed us to show trust depends on associating the partner with positivity, not just on activating positive thoughts. We then measured trust in the partner’s caring and commitment (e.g., “I am confident my partner will always want to stay in our relationship”) and perceptions of the partner (e.g., “attractive,” “intelligent,” “warm”) in both experiments.

p.43

Participants subliminally conditioned to associate their partner with positivity felt safer. They reported greater trust in their partner’s caring and commitment than participants in the neutral conditioning condition in both experiments, suggesting that experiencing a more positive automatic evaluative association to the partner gave them an inarticulate reason to feel safe. In the second experiment, participants subliminally conditioned to associate their partner with positivity also reported greater trust than participants simply primed with positivity. However, participants subliminally conditioned to associate their partner with positive words did not report more positive evaluations of their partner relative to control participants. These divergent effects suggest that immediate affective associations to the partner provide an implicit means of assessing whether the partner is safe to approach, not necessarily whether the partner is desirable to approach. Although this might seem counter-intuitive, it echoes the point of Fiske et al. (2006) when they identified safety (i.e., “Is this person a friend or foe?”) and value (i.e., “Is this person worth befriending?”) as fundamental and separable dimensions of social perception. The fact that automatic attitudes signal partner safety, not simply partner value, also makes functional sense given the embodied nature of attitudes.

In sum, the physicality of doing is bound up in the mentality of thinking because thinking is ultimately for doing. Trust is ultimately for doing too. People are motivated to gauge their partner’s trustworthiness so they “know” what actions to take to satisfy the goal to keep safe and protected from harm (Murray & Holmes, 2009). Because automatic attitudes translate past experience with an attitude object into future action, automatic partner attitudes are an efficient means of embodying trust. As we have seen, behavioral experience interacting with a partner conditions more or less positive automatic evaluative associations to the partner. Like any other automatic attitude, such associations function to keep us safe (Alexopoulos & Ric, 2007; Banaji & Heiphetz, 2010; Chen & Bargh, 1999). For instance, priming positively evaluated objects automatically activates the behavioral tendency to draw objects in one’s environment closer to oneself, whereas priming negatively evaluated objects automatically activates the behavioral tendency to push objects away (Chen & Bargh, 1999). Subliminally priming positive-affect words (e.g., happy) also automatically activates the behavioral tendency (i.e., arm flexion) to draw closer; subliminally priming negative-affect words (e.g., angry) activates the behavioral tendency (i.e., arm extension) to push away (Alexopoulos & Ric, 2007). Automatic partner attitudes thus signal trust and mark progress toward the goal of being safe precisely because the safety-promoting inclinations to approach accepting and responsive and avoid rejecting and non-responsive partners are embodied in the attitude itself.

p.44

Above the Surface: Reasoned Beliefs

Although reasoning can lead people astray in the choice of jams (Wilson & Schooler, 1991), and romantic partners (Wilson & Kraft, 1993), people still need to explain their beliefs to themselves and others (Kunda, 1990). Consequently, the capacity to articulate and explain why trust in a partner is rational and well reasoned also provides an important marker of trust.

Tooby and Cosmides (1996) used the logic of the bankers’ paradox to delineate the beliefs most likely to afford reason to trust. The bankers’ paradox refers to the fact that people most need “loans” of interpersonal sacrifice and good will when they are bad credit risks. When people are sick, distressed, or fearful, they need the aid afforded by close interpersonal ties. But, when something is wrong, people are least able to repay any help they receive. For people to survive to reproduce, they need to discriminate committed and loyal friends they can trust to sacrifice for them from fair-weather friends who will reject them as soon as the going gets tough.

Culturally, people see being irreplaceable as the key to securing another’s commitment and loyalty (Tooby & Cosmides, 1996). Possessing qualities that make one indispensable to select friends guarantees they have reason to stick around when it is costly (Eastwick & Hunt, 2014). Given such cultural constraints, people need to be able to make their partner’s commitment to them “add up” in light of everything they know about the social economics of relationships. They need to be able to offer evidence and reasons why their partner would see them as special and want to be loyal to them over other, potentially less costly, partners (Murray & Holmes, 2011). Our research suggests that these reasons to trust are represented cognitively as “if-then” rules linking evidence of special value (IF) to the tendency to trust (THEN).

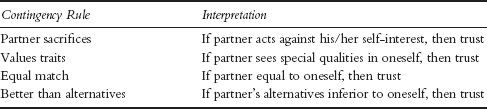

What Reasons Matter?

Table 3.1 lists four trust contingencies we identified (Murray & Holmes, 2009, 2011). Over time in relationships, people report greater trust in their partner’s commitment when they witness their partner’s forgiveness and personal sacrifices on their behalf (Wieselquist et al., 1999). The “partner sacrifices” rule thus specifies Katy has greater reason to trust in Todd when he is willing to act against his own self-interest for her betterment. In ongoing relationships, people who believe their partner regards them as more warm, understanding, intelligent, and attractive (etc.) also report greater trust in their partner’s commitment (Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000; Murray, Holmes, Griffin, Bellavia, & Rose, 2001). The “values traits” rule thus specifies that Katy should trust more in Todd when he sees more positive qualities in her (Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000; Murray et al., 2001; Murray, Rose, Bellavia, Holmes, & Kusche, 2002).

p.45

TABLE 3.1 The Reasons to Trust

The “equal match” rule specifies that Katy further has reason to trust in Todd if she is at least as good a person as he (Derrick & Murray, 2007; Murray et al., 2005). This reason to trust recognizes the power of fairness norms in limiting one’s romantic options (Berscheid & Walster, 1969). In tacit observation of this rule, people use their sense of their own value in the interpersonal marketplace to set their sights on attainable romantic prospects (Leary & Baumeister, 2000; Lee, Loewenstein, Ariely, Hong, & Young, 2008). For instance, people who perceive themselves less positively on interpersonal traits, such as warm, intelligent, attractive, and sociable, set lower aspirations for an ideal partner (Campbell, Simpson, Kashy, & Fletcher, 2001; Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 1996a, 1996b). People thus make it easier to believe that a partner is likely to be trustworthy by pursuing partners who are equal to them and more likely to value them.

Finally, the “better than alternatives” rule specifies that being superior to a partner’s alternatives gives Katy still more reason to believe she can trust in Todd. Such comparisons cue the partner’s trustworthiness because fair-trade norms also constrain the partner’s romantic options (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). Todd’s commitment can waver when the life that he might have with an alternative partner looks better than his life with Katy (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). Because the entreaties of available and better-matched alternatives can pose real temptation, Katy’s sense of her value to Todd also requires tracking how she stacks up against his best options. In this social comparative metric, believing her worth exceeds Todd’s most viable alternatives signals trust because her relative superiority makes her harder to replace (Murray et al., 2009).

Dynamic Changes: The Nature of the Situational Risks

You may be deceived if you trust too much,

But you will live in torment if you do not trust enough.

Crane’s sage words about the dangers of trusting either too much or too little highlight the situational specificity of safety. If Katy trusts too much, and asks Todd for a sacrifice he is not willing to give, she might be setting herself up for disappointment. But if she doesn’t trust Todd enough, and keeps her desires to herself, she could never benefit from his willingness to sacrifice on her behalf, which sets her up for even more enduring hurt. Because Katy needs to anticipate Todd’s actions across a variety of situations, trust needs to be sensitive to situational risk to be a functional signal of progress toward safety and the state of mutual dependence.

p.46

The arrows impinging on the trust iceberg in Figure 3.1 capture such situational influences. Situations vary in risk because some situations are more likely to tempt partners to be rejecting and non-responsive (Kelley, 1979; Murray & Holmes, 2011). Consider the difference between Katy wanting Todd to meet her parents on a weekend when he is itching for an out-of-town trip (a low-risk situation) to wanting him to sacrifice a study weekend right before his bar exam (a high-risk situation). In the high-risk case, Todd has a much stronger incentive to refuse her request because his personal goals more strongly oppose her goals. High-risk situations essentially threaten or unsettle trust, functioning to tip or submerge the iceberg, because they raise the stakes. These situations raise the functional threshold for the level of trust it takes to feel safe because Katy has to put herself much further out on a psychological limb when she asks Todd for a major than a minor sacrifice. Consequently, such high-risk situations stir feelings of unease and distrust in Katy to ensure that she is not taking any unnecessary risks.

Overall and Sibley (2008) used a daily diary methodology to better understand the situational parameters that cue reason to trust versus distrust the partner. Participants completed interaction diaries whenever they interacted with their romantic partner for 10 minutes or longer. In each interaction, participants rated how accepted they felt by their partner as a marker of trust. They also quantified risk by rating how much personal influence or control they had in the interaction (i.e., less control = more risk, like Katy in the bar exam scenario). In those situations where people felt especially vulnerable and powerless, they expected their partner to be much more rejecting. Situations where people feel especially vulnerable and powerless are ones that involve inequality in dependence because one person is more in need of the other’s cooperation. In the weekend scenario, Katy cannot get her wish for Todd to meet her parents unless Todd give her his full cooperation, but Todd can study as he planned without any cooperation from Katy at all. To sum up, Overall and Sibley (2008) make two important points. The first is that trust can vary from one situation to the next (see also Simpson, Rholes, & Phillips, 1996). The second is that situations that involve significant physical, emotional, or psychological unilateral vulnerability to the partner’s potentially hurtful actions move people further from the goal of being safe. These situations have a distinct signature: Needing something from a partner, but feeling relatively powerless to compel it. Being at a partner’s mercy, literally and figuratively.

Restoring Goal Progress: Motivated Perceptual and Behavioral Tactics

Mutual dependence is the requisite condition for safety (Drigotas & Rusbult, 1992). Consequently, situations that impose the perception of relative powerlessness and vulnerability – such as Katy wanting Todd to sacrifice his plans for her – threaten safety goal pursuits because they amplify the risk of harm. People can restore safety in such risky situations by restoring mutual dependence, either in perception or actual fact. As we see next, Katy can restore safety by (1) increasing Todd’s dependence on her or (2) decreasing her dependence on Todd (Murray & Holmes, 2009). Such motivated machinations can be perceptual or behavioral in nature.

p.47

Increasing Partner Dependence

As we have said, people do not have direct access to the contents of their partner’s consciousness. They instead use a mindreading proxy – trust – to gauge the strength of their partner’s dependence and commitment to them (Murray & Holmes, 2009). This peculiarity in the perception of partner dependence means that motivated perceptual biases could afford Katy one ready means of increasing Todd’s perceived dependence on her (Balcetis & Lassiter, 2010). Namely, she could make herself feel safer simply by “seeing” testament to Todd’s commitment to her in his behavior (Murray et al., 2002). For instance, she might engage in a biased search through memory for evidence, such as the especially thoughtful gift Todd gave her on her last birthday, to convince herself that he really does depend on her and care about making her happy (Kunda, 1990). She might also flexibly change her criteria for dependence and trustworthiness to exclude any time he went to someone else for support (Dunning, Meyerowitz, & Holzberg, 1989). For such biased perceptions to effectively restore safety, they should function relatively automatically – that is, without intention or awareness (Bargh, Schwader, Hailey, Dyer, & Boothby, 2012). After all, Katy would probably take little comfort in a newfound sense of safety if she knew that wanting to see Todd as caring for her had systematically biased what she saw in him.

Feeling powerless and vulnerable to hurt and rejection by a romantic partner can indeed elicit an automatic tendency to “see” greater evidence of trustworthiness. This perceptual bias is so powerful that priming vulnerability to a specific romantic partner elicits a general tendency to see novel others as dependent and trustworthy. Koranyi and Rothermund (2012a) made this point in a series of inventive experiments. In one study, experimental participants imagined stressors that could seriously threaten the stability of their relationship (e.g., long period of physical separation). Controls imagined stressors that could threaten their satisfaction at work. Participants then judged the trustworthiness of 12 faces. Participants primed with thoughts of interpersonal vulnerability actually perceived greater evidence of trustworthiness in the faces of strangers than control participants. Being interpersonally unsafe made them see what they needed to see – “evidence” that others are unlikely to hurt them. In a further study, experimental participants imagined their romantic partner wanted to study abroad. Controls imagined they were suffering from an intense toothache. Participants then played a one-shot trust game with an anonymous stranger. In this game, the participant chooses how much of his/her financial endowment to send to a co-player, knowing that the amount he/she sends will be tripled and the co-player will then choose how much money to return. Greater outlays of money on the participant’s part require trusting the co-player to reciprocate and share his/her gains. Being vulnerable resulted in people seeing the trustworthiness they needed to see in their partner in the person they just happened to be depending on at that particular moment. Participants primed with the thought of their partner abroad donated more money than control participants.

p.48

Of course, the powers of such perceptual biases are limited. In the context of an actual relationship, wishing does not make it so. Believing a partner is dependent is one thing, but actually making the individual more dependent and thus trustworthy is even better. This practical constraint suggests that a certain kind of motivated behavioral intention could afford Katy a further means of increasing Todd’s dependence on her. In situations where Katy feels inferior to Todd, she might make herself safer and less vulnerable by finding quick concrete ways to make herself especially useful and valuable to Todd. However, cooking Todd’s favorite meals or getting his favorite books from the library probably wouldn’t be all that effective in making Katy feel safe if she realized she was doing all of these things just to make him depend on her. Conceivably, such tacit awareness might even undermine her trust in Todd. Such motivated behavioral intentions should instead guide Katy’s behavior without her awareness.

An ongoing study of newlywed couples provided initial evidence that working models of relationships do indeed contain implicit procedural knowledge for restoring mutuality in dependence (Murray, Aloni, et al., 2009). Just after they married, the newlyweds in this study completed a 14-day daily diary. These daily reports allowed us to pinpoint the safety-restoring behaviors that feeling inferior to a partner elicits. On days after these newlyweds felt especially concerned about measuring up to their partner, they took action to restore mutuality in dependence. They made sure their partner depended on them by doing practical and tangible favors for them, like packing lunches and finding lost keys. This motivated safety-restoring behavior also seemed to occur automatically. Feeling acutely inferior to the partner on Monday elicited dependence-eliciting behavior on Tuesday controlling for Tuesday’s feelings of inferiority to the partner. Thus, feelings of inferiority that people could no longer consciously report nonetheless motivated compensatory efforts to secure the partner’s dependence. Still more impressive, this remedial response worked. On days after people did more practical and tangible favors, their partner reported being more committed!

To study this safety-restoring dynamic in the lab, we had to find a way to induce worries about the partner’s dependence on the relationship without participants really being aware of the source of their worries. We took advantage of people’s knowledge of the exchange script to do this. This cultural script specifies that partners need to make equitable contributions to the relationship to avoid being replaced (Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). Consequently, priming this cultural script should activate concerns about measuring up to the partner. In one experiment, we asked participants to evaluate how appealing personal ads would be to other people (Murray, Aloni, et al., 2009, Experiment 2). In the exchange priming condition, these ads emphasized the romantic hopeful’s expectation of making an equitable or matched trade. In the control condition, the ads invoked no such expectation. In the second experiment, we superimposed pictures of U.S. coins on the computer screen to prime the economic metaphor that quantities are bought and sold. In the control condition, we superimposed pictures of circles (Murray, Aloni, et al., 2009, Experiment 3). Then we measured concerns about measuring up to the partner and consequent intentions to engage in behaviors that could increase the partner’s dependence (e.g., “cooking for my partner,” “keeping track of my partner’s school schedule,” “remembering my partner’s important appointments”). In both experiments, participants primed with the exchange script reported greater concerns about measuring up to their partner. They also reported much stronger intentions to do concrete things to make their partner depend on them.

p.49

Decreasing Own Dependence

The research just reviewed suggests that people can restore safety by perceiving (Koranyi & Rothermund, 2012) and even physically creating evidence that their partner really does depend on them (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009). Because safety depends on mutuality in dependence, motivated manipulations of Todd’s dependence are not Katy’s only option for restoring safety. People can also restore safety through motivated manipulations of their own dependence. In situations where she is feeling relatively vulnerable and powerless, Katy can regain safety by trusting and relying less on Todd. Todd simply cannot hurt Katy if she won’t let him get close enough to her to do so (Murray et al., 2006). Rather than pulling the partner in, people can restore mutual dependence by withdrawing themselves. As we see next, people can reduce their own dependence and pull away from their partner through complementary motivated perceptual biases and distance-producing behavioral intentions.

We realize this might seem paradoxical, but for someone who is feeling vulnerable and powerless, there is safety to be gained through greater distrust and suspiciousness. People who are highly anxious and fearful provide a case in point. Even though one might expect a spider phobic to be motivated not to see spiders, people who experience such anxieties are especially disposed to see the target of their fear. Being quick to perceive a tangled ball of thread on the floor as a spider is actually functional for people who fear spiders because such vigilance better equips them to avoid the targets of their fears (Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1990; Mineka & Sutton, 1992). For instance, threatening words, such as “injury” or “criticized,” automatically capture attention for people high in generalized anxiety (MacLeod, Mathews, & Tata, 1986).

p.50

Being suspicious and vigilant in a relationship context similarly appears to function to ensure safety from both physical and psychological harm. Distrust and suspicion can promote safety for a very fundamental reason. People generally only let themselves risk closeness to another when they are sure another’s acceptance will be forthcoming (Murray et al., 2006).3 Perceiving reason to distrust thus motivates people to distance themselves from a potential source of harm – just like physical pain motivates people to remove their hand from a hot stove (MacDonald & Leary, 2005). If Katy is quick to perceive the potential for rejection on Todd’s part, she is less likely to let herself be caught up in a situation where she could be hurt (Murray, Bellavia, Rose, & Griffin, 2003; Pietrzak, Downey, & Ayduk, 2005). Ironically, in some situations, feeling less trusting can thus signal greater safety than feeling more trusting.

For instance, people who chronically worry about being vulnerable to a partner are quick to interpret their partner’s negative mood as anger directed toward them (Bellavia & Murray, 2003). Such a motivated perceptual bias on Katy’s part restores safety by motivating her not to depend on Todd in situations where she might get hurt. Consistent with this logic, directly priming reasons to distrust others automatically activates the motivated behavioral intentions to impose greater physical distance between oneself and the source of such hurts. As one example, people subliminally primed with the name of a consistently rejecting significant other were quicker to identify synonyms of social distance, such as “distance,” “dismiss,” “withdraw,” and “detach” in a lexical decision task (Gillath et al., 2006). Similarly, people who vividly recounted a time when their dating partner had hurt them were quicker to identify distancing words, such as “oppose,” “condemn,” “angry,” “blame,” “hate,” “annoy,” and “accuse,” in a lexical decision task (Murray, Derrick, Leder, & Holmes, 2008).

Being quicker to respond to distancing words does not necessarily mean that people would actually choose to avoid others when they are feeling vulnerable, but such behavioral evidence also exists. Feeling suspicious and distrustful motivates people to distance themselves from diagnostic social situations where they could learn how others feel about them (Beck & Clark, 2009). For instance, people who had just thought of someone they distrusted chose not to learn what a new interaction partner thought of them. Unlike control participants who welcomed this opportunity, distrust-primed participants effectively closed off the opportunity for a relationship before it even had the chance to begin. People who were chronically distrustful and suspicious of others also preferred teachers to assign them to work partners rather than risk finding out which of their classmates actually wanted to work with them (Beck & Clark, 2009).

Fitting Motivation to Context: Situation Calibration

To return to Crane’s observations, people face a dilemma between trusting too much and trusting too little because they cannot both trust and not trust a partner in any one situation. Motivated perceptual biases that highlight the partner’s worthiness of trust foreclose the possibility of pursuing safety through suspicion, vigilance, and distance. Because some means of precluding safety preclude others, we now turn to the next logical question: What factors determine whether people restore mutuality in dependence through automatic perceptual biases and behavioral intentions that either increase the partner’s dependence or reduce their own dependence? These automatic machinations depend on the (1) nature of the situational threat and (2) overall progress toward the goal of being safe from harm as marked by trust.

p.51

The Situation

In the preceding pages, we described studies that reveal two opposite effects of priming interpersonal vulnerability. Vulnerability can increase both trust and distrust! Priming thoughts of a partner studying abroad motivates people to see trustworthiness in others (Koranyi & Rothermund, 2012), and priming inferiority motivates people to engage communally toward their partner (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009), but priming thoughts of a partner being overtly untrustworthy and rejecting motivates people to be suspicious and hostile (Murray et al., 2008).

These seemingly conflicting findings echo the third theme of this book. For motivation to infuse romantic life in ways that facilitate the pursuit of belongingness, the specific goal (whether safety or value) that monopolizes attention, inference, and behavior needs to be sensitive to situational affordances. In situations that favor the pursuit of safety over value goals (or vice versa), the specific means of goal pursuit also needs to be flexible and sensitive to situational affordances. Katy can make progress toward her goal to be safe by (1) pulling away from Todd or (2) drawing Todd closer to her. Which particular means of safety goal pursuit she favors in any given situation needs to adjust to the affordances of that situation.

Not all situations that involve vulnerability and powerlessness have the same affordances. Some situations simply highlight the possibility for a partner to be hurtful, an eventuality that may or may not unfold. Imagining a partner going abroad highlights the possibility that a partner might not be available, but it does not guarantee it. Similarly, feeling inferior to the partner highlights the possibility that a partner’s eye might wander, but it does not guarantee it. However, thinking of a concrete time when a partner actually did something very hurtful makes partner rejection a hard, cold actuality. In our thinking, situations that prime the possibility of partner rejection better afford the opportunity to prevent hurt by increasing the partner’s dependence – essentially going on the motivational offense. In contrast, situations that prime the actuality of partner rejection better afford the opportunity to blunt hurt by distancing oneself from the source of the pain – essentially going on the motivational defense. Consistent with this affordance logic, people respond differently to the experience of being rejected than being ignored (where rejection is a possibility, not an actuality). Specifically, people reminded of a time when others rejected them withdraw from others to avoid another hurtful interpersonal loss. In contrast, people reminded of a time when others ignored them draw closer to others in the hopes of gaining acceptance (Molden, Lucas, Gardner, Dean, & Knowles, 2009). Similarly, being rejected by a spouse has a palpably different effect on daily marital interactions than feeling inferior to a spouse. Feeling rejected motivates people to engage in selfish and hurtful behavior that decreases their dependence on their partner. Feeling inferior instead motivates people to engage in kind and communal behaviors that increase their partner’s dependence on them (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009; Murray, Bellavia et al., 2003).

p.52

Fitting Motivation to Context: Trust Calibration

As we have just seen, some situations better afford one means of restoring safety over another. In our theoretical writing on interdependence, we argue that specific situations have the power to compel behavior because diagnostic features of situations are included within the behavioral representations used to navigate such situations (Murray & Holmes, 2009). For instance, feeling inferior to Todd automatically primes Katy’s intention to increase his dependence on her because her mental representations of relationships contain procedural knowledge that links threatening situation features (IF) to threat-mitigating behaviors (THEN).

The power such IF-THEN rules have to compel behavior is limited though. To return to the car-driving metaphor Baumeister and Bargh (2014) introduced, the unconscious may be responsible for most of the mechanics of driving the car, but the driver can still decide whether the car is veering off in the wrong direction. Therefore, Katy might only act on an automatically activated perceptual bias or behavioral intention if such inclinations feel “right” to her (Murray & Holmes, 2009). Whether such intentions feel “right” depends on how much overall progress people have made toward the goal of being safe as marked by trust.

According to our iceberg model, the overall experience of trust marks the best means of making progress toward safety goals. It does so through automatic evaluative associations to the partner and reasoned beliefs (Figure 3.1). More positive evaluative associations or more optimistic reasoned beliefs generally afford increased trust, which creates a cross-situational sense of being closer to the goal of being safe. Less positive evaluative associations or less optimistic reasoned beliefs afford decreased trust, which creates a cross-situational sense of being further away from the goal of being safe. More readily attainable goals surely have different psychological effects than less readily attainable goals. Therefore, Katy and Todd’s subjective experience of insufficient (or sufficient) progress toward the goal of being safe should affect how vigilantly each responds to situational setbacks in this goal pursuit.

In specific situations that move him further from the goal of being safe, a more trusting Todd likely still feels closer to the desired goal of being safe than a less trusting Katy (Murray, Griffin, Rose, & Bellavia, 2003). Greater overall goal progress gives a more trusting Todd a greater psychological cushion in the pursuit of safety than a less trusting Katy. Any misstep is not going to hurt a more trusting Todd as much as a less trusting Katy because he is already closer to the desired goal of being relatively safe from hurt. The metaphor of a foot race is an apt one here. A faster runner can better afford to run a riskier race with more potential for misstep than a slower runner because the faster runner is already closer to the finish line and can more readily recoup lost ground. The same principle appears to apply to trust and the pursuit of safety.

p.53

Being able to afford missteps in the pursuit of safety goals gives a more trusting Todd the luxury to pursue a riskier motivational course. In situations that highlight his vulnerability to Katy’s actions, he can better afford to simply believe in Katy’s dependence and trustworthiness while discounting automatic inclinations to take quick behavioral steps to restore mutual dependence. However, a less trusting Katy cannot afford any missteps in her pursuit of safety in specific situations because she cannot afford to fall even further short of this goal. This leaves her with little choice but to pursue a more cautious motivational course that prioritizes taking quick and immediate perceptual and behavioral action to guard against any further threats to safety. The empirical examples we highlight next illustrate exactly how chronic implicit and explicit markers of trust can control the actions people take to restore safety.

Automatic Evaluative Associations

Imagine that Todd has just handed Katy an itemized list of every last one of her personal qualities that annoy him. Such a vulnerability-inducing situation automatically activates behavioral inclinations associated with the situation itself. In this particular case, being rebuked by the partner activates the inclination to withdraw (Murray et al., 2008). However, such situations also activate automatic attitudes toward the partner because this marker of trust allows people to read their partner’s mind. Just as automatic attitudes embody bodily intentions to approach safe and avoid unsafe objects (Chen & Bargh, 1999), automatic partner attitudes also embody representations of partner proximity and availability (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003; Williams & Bargh, 2008b). Experiencing more negative automatic evaluative associations to the partner signals the partner’s physical and psychological unavailability, marking insufficient progress toward safety. However, experiencing more positive automatic evaluative associations to the partner signals the partner’s physical and psychological availability, marking greater overall progress toward the goal of being safe.

Consequently, in vulnerability-inducing situations, a less trusting Katy is more likely to act on the automatic inclination to reduce dependence. Katy’s more negative automatic attitude should motivate her to guard against any further threats to safety and reinforce the situational impetus to withdraw and reduce her dependence on Todd. However, Todd’s more positive automatic attitude toward Katy marks greater progress toward the goal of being safe. Being closer to this goal should strengthen Todd’s goal to connect to Katy, making it easier for him to suppress the competing inclination to withdraw (Fishbach, Friedman, & Kruglanski, 2003).

p.54

We created an experimental analogue to this scenario to examine just these possibilities. We brought dating couples into the lab and measured their automatic attitudes toward one another using the IAT. We then led one member of the couple to believe that his or her partner had a laundry list of complaints about that individual’s personal qualities. We first told couples that they would each be completing the same measures in tandem throughout the study. We then sat partners back to back at two separate tables. In the experimental condition, we gave the target participant (let’s say, Katy) a one-page questionnaire asking her to list important qualities in Todd that she disliked. The instructions also stipulated, in bold type, that Katy did not need to list any more than one quality. So, typically, Katy listed one of Todd’s faults, stopped, and sealed her questionnaire in an envelope. Then she had to wait for Todd to finish before she could start the next experimental task. But as she sat, Todd kept writing and writing! Todd wrote so copiously because, unbeknownst to Katy, he was asked to list at least 25 items in his residence. Almost invariably Todd took much longer to complete the writing task than Katy – which gave Katy considerable time to worry that Todd was being hurtful and rejecting. In the control condition, both partners completed the one-fault listing task and neither had any reason to think the other had a long list of complaints.

Next we measured the dependent variable – automatic inclinations to increase (vs. decrease) dependence on the partner. Under the guise of doing a categorization task, participants had to decide (yes/no) whether words appearing on the computer screen could ever possibly be used to describe their partner. These words were either trait words, like warm or stubborn, or object words, like truck. If the automatic inclination to reduce dependence on Todd is controlling Katy’s behavior, we reasoned that she should be slower to identify positive traits in Todd on this task. Why? Questioning his value should make her less dependent on Todd and his approval, thereby restoring safety in a situation where she is feeling rejected.

p.55

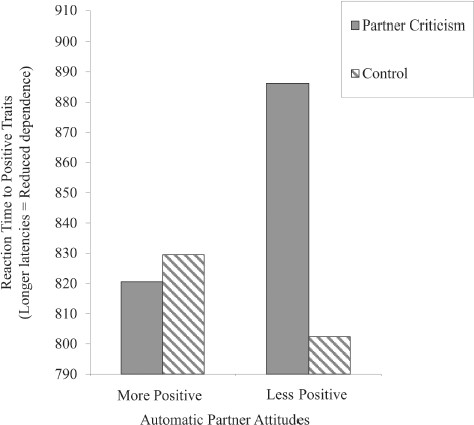

FIGURE 3.2 More Positive Automatic Partner Attitudes Protect Against Partner Criticism. (Adapted from Murray, S. L., Pinkus, R. T., Holmes, J. G., Harris, B., Gomillion, S., Aloni, M., Derrick, J., & Leder, S. (2011). Signaling when (and when not) to be cautious and self-protective: Impulsive and reflective trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 485–502. Copyright American Psychological Association; adapted with permission.)

Figure 3.2 presents the results. We plotted reaction times to positive-trait words as a function of experimental condition (partner rejection vs. control) and automatic partner attitudes. People with less positive automatic partner attitudes (on the right) automatically reduced dependence; they were markedly slower to identify positive traits in their partner in the partner rejection than in the control condition. However, participants with more positive automatic partner attitudes (on the left) sustained dependence; they were just as quick to identify positive traits in their partner in the partner rejection condition as they were in the control condition. To return to Katy and Todd, these results suggest that people who are less trusting restore safety in ways that minimize the potential for further harm. Questioning a partner’s value, and thus reducing dependence on the partner, does just that. However, people who are more trusting take a riskier motivational course and suppress automatic intentions to reduce their own dependence that may not feel “right” given their greater progress toward safety.

Reasoned Beliefs

Katy’s automatic evaluative association to Todd is not the only marker of trust activated in situations that highlight her vulnerability and powerlessness. The reasons she can articulate for trusting in Todd are also activated (Simpson, 2007). Believing that Todd sees her as both funny and warm and overly sensitive and demanding gives her reason to question whether he truly values her (Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000). Consequently, in risky situations, a less trusting Katy may have greater difficulty explaining Todd’s commitment. This difficulty articulating reasons to trust marks insufficient progress toward the goal of being safe and should motivate Katy to cautiously guard against further threats to safety. Therefore, being less trusting should reinforce Katy’s situationally provoked temptation to reduce dependence and minimize her vulnerability. In contrast, Todd’s greater ease explaining why Katy stays with him gives him the luxury to pursue a riskier motivational course because the prospect of rejection is less likely and hurtful. Therefore, being more trusting should motivate Todd to override the temptation to withdraw and instead restore safety in ways that preserve his trust and dependence on Katy.

p.56

A daily diary study provided one of our first tests of these hypotheses (Murray, Bellavia, et al., 2003). In this study, we indexed reasons to trust in the partner through people’s beliefs about their partner’s regard for them. To do this, we asked participants to describe how they believed their partner saw them on 20 or so interpersonal traits. Believing that Katy sees him as warm, responsive, and not at all stubborn gives Todd greater reason to trust in Katy. We then asked both partners to complete a standardized diary each day for 21 days. Each partner recorded what had happened each day (e.g., “we had a fight”); reported confidence in the other’s caring (e.g., “I felt rejected or hurt by my partner”); and indicated whether they engaged in behaviors that could increase/decrease dependence (e.g., “I insulted or criticized my partner”).

People who could readily point to qualities their partner valued in them restored safety through perceptual biases that increased their own dependence. They even “saw” greater evidence of trustworthiness in negative than positive partner behavior. They reported greater confidence in their partner’s caring on days after they had serious conflicts or witnessed their partner engaging in manifestly hurtful behavior (relative to better days). In contrast, people who could not as readily point to qualities their partner valued in them restored safety through motivated perceptual biases and behavioral intentions that reduced their own dependence. They interpreted events as potentially innocuous as their partner simply being in a bad mood as testament to rejection. On days after they felt acutely rejected, they also engaged in rejecting behavior that communicated how little they needed their partner (Murray, Bellavia et al., 2003).

Differences in the safety-restoring tactics of more or less trusting people also emerged in an observational study of couples negotiating sacrifices (Shallcross & Simpson, 2012). Each partner in this study first completed a pre-interaction measure of trust tapping chronic perceptions of their partner’s caring and reliability. Next, they tasked one member of the couple (e.g., Katy) to initiate a discussion with the other (e.g., Todd) about something that she personally wanted to do that required a major sacrifice on his part. In a subsequent discussion, Todd was similarly tasked to discuss a major sacrifice he wanted from Katy. Each partner then completed a post-interaction measure of state trust and objective raters coded the videotaped interactions for how responsively and accommodatingly partners behaved toward one another.

p.57

These ratings allowed the researchers to index both the objective threat to safety evident in the interaction and the safety-restoring tactics partners implemented. For instance, Todd’s behavioral responsiveness to Katy’s sacrifice request indexed the level of threat Katy experienced when she made herself vulnerable to Todd (with less responsive behavior indicating greater threat). Katy’s behavioral responsiveness to Todd after she requested her sacrifice in turn indexed how she restored mutuality in dependence, and thus, her own state of safety (with less responsiveness behavior indicating her inclination to reduce her dependence). People who initially reported greater trust in their partner took greater psychological leaps of faith to restore safety than people who were less trusting. When highly trusting people requested a sacrifice, they saw greater “evidence” of accommodation and responsiveness in their partner’s behavior than objective observers. In fact, highly trusting requestors reported increases in trust over the interaction when their partner engaged in less accommodative and responsive behavior. They essentially saw the evidence of responsiveness they needed to see to stay safe. In contrast, the motivation to restore safety had an opposite effect on the perceptions and behavior of less trusting people. When less trusting people requested a sacrifice, they behaviorally withdrew from partners even when their partner tried to be responsive and accommodate them.

Because relationships extend in time, a partner’s hurtful behaviors are not locked in the past. The memory of these behaviors can intrude on the present to remind people of the risks of depending on their partner. When this happens, the motivated perceptual biases that color perceptions of the present also need to color perceptions of the past to restore safety (Luchies et al., 2013). Luchies and her colleagues (2013) studied such reconstructive memory biases in a series of diary studies. They asked participants to record their partner’s every transgression daily, to rate every transgression’s severity and hurtfulness, and to report whether or not they had forgiven each misdeed. Several weeks later, the researchers reminded participants of each transgression and they asked them to recall how they had felt about the transgression when it happened. People who initially reported greater reason to trust in their partner restored safety in the face of this threat through motivated reconstructive biases that whitewashed the past. More trusting people remembered partner transgressions as being less frequent and hurtful, and more forgivable than they had originally perceived them to be. However, less trusting people remembered their partner’s transgressions as being even more frequent, hurtful, and unforgivable than they had originally perceived them to be. Less trusting people essentially restored safety in the face of this threat by reminding themselves exactly why they should keep a safe distance from their partner.

The Two Sources Will Not Always Agree

Our running examples of a less trusting Katy and more trusting Todd make the implicit assumption that each uniformly trusts or distrusts the other. That is not always going to be the case. Automatic partner attitudes and reasoned beliefs can send different messages about a partner’s trustworthiness because they draw on different sources of information (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006; LeBel & Campbell, 2009; Lee, Rogge, & Reis, 2010; Scinta & Gable, 2007). Automatic partner attitudes usually develop “bottom-up” – subliminally conditioned through behavioral interaction. Beliefs about a partner’s trustworthiness usually develop “top-down” – informed by introspection and abstract reasoning (Fazio, 1986; Gregg et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2000). Consequently, Katy could develop positive automatic attitudes toward Todd because he has always treated her well, but still question whether she can really trust him because she cannot readily explain why she should feel safe in his presence. We return to this complication in Chapters 5 and 6 when we discuss motivational conflicts between the goals to be safe from harm and perceive meaning and value.

p.58

When Safety Becomes a Preoccupation

We began this chapter arguing that automatic partner attitudes and reasoned beliefs mark the best means of making progress in the pursuit of safety by giving people the means to mindread their partner’s dependence and commitment. We then transitioned to discuss how situations that highlight one partner’s relative vulnerability and powerlessness make safety an acutely pressing concern. Next, we described how the goal to restore mutual dependence, and thus safety, activates different perceptual biases and behavioral intentions as a function of trust. For a less trusting Katy, safety comes in motivated perceptual biases and behavioral intentions that reduce her dependence on Todd. But, for a more trusting Todd, safety comes in motivated perceptual biases and behavioral intentions that increase Katy’s dependence on him. Before moving on to the pursuit of value goals, we need to make one final point about safety pursuits: Safety is more likely to become a chronic and preoccupying goal in some relationships than others. By preoccupying, we mean that the goal to be safe is both more readily activated and less readily satiated. We develop this theme in Chapter 5 and just foreshadow these arguments here.

The first reason why safety can become a preoccupying goal comes from the power the life stage of the relationship has to put partners in vulnerable situations. Certain transitions in relationships, such as moving in together (Kelley, 1979) or the birth of a first child (Doss et al., 2009), dramatically increase interdependence. Caring for a newly arrived infant would unilaterally increase the number of ways in which Katy had no choice but to rely on Todd; even her capacity to eat, sleep, and bathe would require his cooperation. Such “enforced” interdependence is going to create more situations where partners have unequal dependence. Frequent exposure to such situations could turn safety into a chronically accessible goal through basic principles of priming and spreading activation. Each new situation of vulnerability activates the goal to be safe, which then makes the subsequent activation of this goal more likely in any situation that bears close enough resemblance to the original one (Higgins, 1996).

p.59

The second reason why safety can become a preoccupying goal rests in the power that partners have to behave in ways that make it objectively more or less difficult to trust them across situations. Partners differ in interaction risk because they differ in the dispositions they bring to the relationship (Murray & Holmes, 2011). For instance, low self-esteem partners present a greater interaction risk because they resist self-disclosure (Forest & Wood, 2011), push partners away when they feel hurt (Ford & Collins, 2010), and demand unrelenting affection and support (Lemay & Dudley, 2011; Marigold, Cavallo, Holmes, & Wood, 2014). Anxiously attached partners provide inconsistent support (Collins & Feeney, 2004) and try to exact guilt in their partners to hold sway over them (Overall, Lemay, Girme, & Hammond, 2014). Partners who are more neurotic are also quicker to cast accusations and blame for mistakes (Karney & Bradbury, 1997). Because difficult partners often behave in uncaring ways, people paired with such partners will more often find themselves questioning whether their partner really needs and depends on them. Consequently, safety is likely to become a chronically preoccupying goal because it stands to be activated in almost any situation that involves the partner (Higgins, 1996).

The third reason why safety can become a preoccupying goal rests in the perceiver and the power personal motivations have to infuse attention, inference, and behavior in relationships. The motivated cognitive processes that allow people to believe that they are smarter or more attractive than they are can also be harnessed to make people believe their partner merits far less trust than they actually do. For Katy to believe that she has good reason to trust in Todd, she has to pretend to know something that is essentially unknowable. She has to look into an uncertain future and simply have faith that Todd will always need and depend on her and want to be there for her, no matter what happens (Holmes & Rempel, 1989). Unfortunately, some people are poorly equipped to find resounding support for this conclusion in the evidence.

Low self-esteem people are a case in point. They are notorious for questioning their value to others (Leary, Tambor, Terdal, & Downs, 1995). They underestimate how much their partner loves and values them even though they are loved just as much as high self-esteem people (Murray et al., 2001). Low self-esteem people cannot quite explain why they should trust their partner for one basic reason: They are unsure of themselves and hesitant to believe anything truly good about themselves or other people for fear they might be wrong (Baumeister, 1993; Heimpel, Elliot, & Wood, 2006). Rather than believe their partner sees them as good and valuable, low self-esteem people self-verify and assume that their partner sees them in the same negative light as they see themselves (Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000). The subversive personal agendas that come with low self-esteem thus make safety a more chronically preoccupying goal. Because low self-esteem people cannot quite convince themselves they have reason to be safe, they see threats to safety at every corner. Vulnerable perceivers essentially learn to associate safety and its pursuit with any situation involving the hint of vulnerability, making its pursuit a habit.

p.60

Conclusion

Shaken by a work-weary Todd’s apparent lack of interest in spending time with her in the past week, Katy decided against asking Todd to go to see her parents for the weekend. Consequently, Todd lost an opportunity to prove his willingness to be trustworthy and responsive to Katy’s needs. The unfortunate outcome to this tale reiterates two important themes to carry forward.

The first is that the outcomes of safety goal pursuits are not necessarily good ones. Through her reticence, Katy lost the hope of getting what she really wanted – Todd meeting her parents. Nonetheless, her actions did keep her safe from being hurt in that particular situation, satisfying the goal to be safe. Though this point might seem paradoxical, it bears emphasis. Satisfying the goal to be safe does not always result in people finding safety and comfort in their partner’s hands. Sometimes people can also find the safety and comfort they seek by taking their outcomes out of their partner’s hands. The second theme to carry forward is that safety goals are not static. Safety is never achieved in some absolute sense, freeing a person from the need to ever again protect against the possibility of hurt. Even though Katy backed away from Todd for this weekend trip, she will still face new situations in her relationship that make her feel vulnerable and uncertain – renewing the need to take some kind of psychological and behavioral precaution to restore safety. With these points in mind about the pursuit of safety, we now turn to consider the second fundamental goal – value.

Notes

1 This conceptualization of trust makes explicit what is usually implicit in measurement. Any construct is more than the sum of its measured parts. In our case, the construct of trust captures “something more” than any method of measurement captures. This “something more” is intangible and intrinsic to the person, an essential property of subjective experience. In this chapter, we use the term “experience of trust” to remind the reader that Katy’s trust in Todd captures something intrinsic to her experience that cannot just be boiled down to responses on a trust scale. Katy’s experience of trust in Todd is dynamic and changing, a complex interplay of automatic evaluative associations, reasoned beliefs, and situational influences. Much as researchers might want to capture lightning in a bottle, collectively we have only begun to understand the complex algorithm involving the different sources of measured influences that create Katy’s experience of trust in Todd and Todd’s experience of trust in Katy.

2 Participants categorized words belonging to four categories: (1) pleasant words (e.g., vacation, pleasure); (2) unpleasant words (e.g., bomb, poison); (3) words associated with the partner (e.g., partner’s first name, partner’s birthday); and (4) words not associated with the partner (Zayas & Shoda, 2005). We contrasted reaction times on two sets of trials to diagnose partners’ automatic attitude toward their partner. In one set of trials, participants used the same response key to respond to pleasant words and partner words (i.e., compatible pairings). In the other set of trials, participants used the same response key to respond to unpleasant words and partner words (i.e., incompatible pairings). The logic of the IAT says reaction times should be faster when the nature of the task matches the nature of one’s automatic associations to the partner. In particular, people who possess more positive automatic attitudes should be faster when categorizing words using the same motion for “partner” and “pleasant” than when using the same motion for “partner” and “unpleasant.”

p.61

3 We explore this risk regulation principle fully in Chapter 5.