Guinness has been brewed at St. James Gate Brewery in Dublin since 1759.

The word “beer” has meant different things to different generations. To ours, it generally suggests pilsner: a slender, elegant beverage as golden as the dawn sun. Pilsners are one of the world’s two superstyles, brewed and sold across the planet. But to an earlier generation, “beer” would have meant just the opposite—a midnight ale, thick and lustrous as a ribbon of velvet. The first superstyle was porter, which was available almost as widely 200 years ago as pilsner is today.

Porters and stouts run a continuum of flavors and strengths as broad as any style brewed, and yet something unites them in a single, easily identified family. Is it their appearance, the always fashionable black? Surely that’s part of it. Who has not watched in fascination as the bubbles in a pint of Guinness do the moonwalk backward into the depths of the pint glass? More important are those elements that communicate richness: a creaminess on the tongue, a density on the palate, and spikes of flavor, variously intense, of coffee, vanilla, plum, chocolate, port, or licorice. Porters and stouts are the rare styles that are both immediately welcoming to the novice and eternally rewarding to the connoisseur. These dark ales are like liquid chocolate. No wonder they once conquered the world. ■

Guinness has been brewed at St. James Gate Brewery in Dublin since 1759.

THE STORY OF porters and stouts is 300 years old and, like any multigenerational epic, stuffed with fascinating subplots, anecdotes, and apocrypha. Porters (and later, stouts) were the first international style, shipped to and then brewed in countries on five continents. But more importantly, they were the first industrial style, brewed on a scale inconceivable before steam power transformed brewing.

We begin the story in England around the turn of the eighteenth century. Brewing was still a rustic art, and the pubs of London poured as many as thirty different types of beer. One of the more common was a smoky, murky brown beer that endured despite its poor reputation (“heavy, thick, and foggy,” in the words of one writer). Yet from this style emerged porter, a more flavorful variation on the old browns, but one that nevertheless relied on the same malt, which would characterize porters for a century and a half.

Maltsters of the day were able to make three basic varieties—pale, amber, and brown malts. Counterintuitively, they took progressively less time to kiln. Pale and amber malts baked slowly and expensively for many hours. Brown malt, the cheapest and worst, was subjected to intense heat for short periods, emerging hard, crusted, and scorched. It could be kilned over fires of straw, which produced fairly clean malt, or wood, which made it smoky; but in neither case was the finished product especially palatable.

Ralph Harwood and His Three Threads. There’s something narratively attractive in the idea of a single origin story. Alexander Graham Bell and the telephone, the Wright brothers and their airplane. For more than 200 years, an obscure, unsuccessful English brewer named Ralph Harwood has gotten all the credit for single-handedly inventing porter—but does he deserve it?

Here’s how the Harwood story goes. The main beers in London in the 1730s were ale (low ABV, made with few hops), beer (robust and hoppy), and twopenny (a pale ale), and it was common for pubgoers to ask for a pint with all three blended together—a way of making a fourth beer on the spot. Harwood, based in Shoreditch, London, hit on the idea of brewing a beer that combined the character of the “three threads” that arrived whole, without the need to blend. The resulting beer, which he called “entire” because it contained all three, was the first porter.

It turns out most elements in the Harwood tale are false, despite their now prominent provenance in histories by some of the most careful writers. In researching the style, the historian Martyn Cornell began finding obvious inconsistencies with other accounts and eventually found the source of the famous three-threads story: a short piece by a writer named John Feltham in a London guidebook from 1802. Feltham got several things wrong. There was a drink called “three-threads” at the time, but according to contemporary observers, the beers were blended in the cask, not at the pub. Feltham compounded this error by conflating the three-threads blends with the practice of reblending parti-gyled batches to make porters. “Entire” didn’t refer to the three threads, as he thought, but to blends of different strengths of the same porter.

Ralph Harwood did exist and he did brew beer in Shoreditch. Yet there’s no evidence from any contemporary source that Harwood was particularly pivotal in the style’s invention. In fact, Harwood went bankrupt in 1747, which would have taken real effort by the inventor of London’s most popular style of beer. A more likely story is also more prosaic. Porters evolved slowly as breweries began to make incremental improvements over time. There’s evidence of this, too. A writer from the mid-eighteenth century remembered that the early versions of porter weren’t very good. (It wasn’t until breweries began to age porter, shortly after his account, that it came into its own.) That writer made no mention of three threads, no mention of Harwood. But we like our single-origin stories, and so the legend of Ralph Harwood is likely to enjoy a long and robust life.

Porter brewers, however, adopted methods of brewing that seemed to mitigate the faults imparted by brown malt. First, they employed a technique known as “parti-gyle brewing.” This involved drawing several batches of beer off a single, massive mash. The first runnings were the most sugar-rich, and each successive beer grew weaker and weaker as the grains were washed of sugars. The brewers followed the same process, but instead of blending the batches to make different strengths of beers (the typical method), they mixed them all back together to make single batches of porter. The brewers called these beers “entire” (sometimes spelled “intire”) because they contained all the mash runnings.

The second important discovery, and the practice that came to define the style, was aging. Porter makers learned that age helped soften the harsh edges of the beer. They stowed their beer in huge, 108-gallon casks known as “butts” to cure (porter was sometimes referred to as “entire butt,” which is, sadly, less amusing when you understand the context). They left it there for at least several months and sometimes as long as two years. This had two practical effects. Freshly brewed porter expressed much of the harsh character of the cheap malt used to brew it. But age mellows beer, and the sharpness and smokiness softened over time. More important, it allowed the beer to be inoculated with wild yeasts living in the casks, which transmuted the beer into deep, complex liquids with the qualities of sherry.

The drink quickly became a hit among London’s working classes, particularly the men who unloaded cargo on the river and distributed it around the city. These workers were known as “fellowship” or “ticket” porters, and before long, the beer they drank was known as porter, too. The early 1700s are not replete with accounts of the brewing market, but it appears that once porter brewers learned to age their product, it took just a couple decades to become the city’s dominant style.

Ticket porters unloading cargo from the Thames gave London’s famous black ale its name.

For the first time near the end of the 18th century, thanks to the steam engine, breweries were able to capitalize on a beer’s popularity by brewing in larger and larger quantities. By harnessing the engine’s power, they were able to mill massive quantities of grain quickly, reliably heat mash water, mix and stir the mash, and pump the beer throughout the brewing process. Breweries could produce ten times the amount of beer with steam power that they could before it—and mechanization meant more consistent batches, to boot.

Steam power didn’t make porters any speedier to age, though, and finding space to let beer sit and ripen for months presented a challenge to London breweries producing hundreds of thousands of barrels annually. If a brewery owned 100 butts, they could produce, say, 200 butts of unaged beer a month—2,400 a year. But if they needed to let the beer cure six months, they could produce only 200 butts in a year. Less-wealthy breweries could do little to remedy the problem, but the rich ones seized their advantage. They began securing warehouse space all over London to store their beer. The large London brewery Whitbread leased a remarkable fifty-four locations. Thrale’s, another major producer, owned 19,000 butts, or two million gallons of aging capacity.

Ale vs. Beer. In modern usage, these two terms are roughly interchangeable. Beer is the larger category, made up of ales and lagers. However, until a hundred years or so ago, the words meant different things to Britons who distinguished brews low in alcohol and hops (“ales”) from those that were robust and hoppy (“beers”). This vital information will serve you well should you happen across an English brewing manual from the eighteenth century or, say, discover time travel.

The emergence of superbreweries fed another phenomenon: world shipping. London sent porter literally around the world. Major destinations included Russia and the Baltic region, India, Australia, and the New World. The British, with their world-traveling fleet, had already been shipping beer to the colonies when porter came on the scene, and rising volumes reflected porter’s popularity. In 1750, Britain sent nearly 14,000 barrels around the world. By 1800, porter-fueled exports jumped to more than 90,000 barrels.

Porter wasn’t the first beer to influence other styles, but it was an order of magnitude more popular than any the world had seen. Porter was such a hot style it was ripe for copying—another first in world brewing—and so copy it other countries did. First the style migrated to breweries in Ireland and Scotland in the 1760s and then it continued to spread. The U.S. was brewing porter by the 1780s, Sweden in the 1790s, Australia around 1800, Russia in the 1820s, South Africa in the 1830s, and Sri Lanka in the 1860s.

Toward the end of the 1700s, porter recipes were evolving. Brown malt was now made by slow-kilning for longer periods of time. When the malt was leeched of nearly all moisture, maltsters subjected it to a flash of very intense heat that caused it to “burst like popcorn.” This was known as “blown” or “porter” malt, and it would be used in English porters for the next hundred years.

Malt prepared like this would have had none of the enzymes needed during fermentation, however. The change in brown malt techniques coincided with the invention in 1784 of the saccharometer, a device that measures fermentable sugars in beer. Brewers realized that pale malts were far more fermentable than darker malts—a fact that keenly interested them. The British government taxed beer based on ingredients; the more efficient the malt was, the less brewers needed, and therefore the less tax they paid. In short order, porter recipes started using a majority of pale malts; the blown malt was added to preserve porter’s familiar flavor and color.

We’re a hundred years into the story, yet porters were still strong, aged brown ales. It was around 1820 that porters finally turned black, thanks to a man named Daniel Wheeler, who in 1817 invented a technique for roasting malt at 400°F until it looked like espresso. (He patented the technique, giving the malt a name homebrewers will recognize to this day: “black patent.”) Shortly after this innovation, breweries began darkening porters with a small amount of the potent black malt—and used less brown malt in the bargain.

During the early 1800s, porters remained essentially a single style, though “stout,” a generic adjective affixed to high-alcohol versions, was creeping into use. The evolution of recipes led to an evolution—and splintering—of style. In England, breweries continued to employ brown malt, but Dublin’s brewers embraced black malts and quit using brown altogether. As in London, Ireland’s breweries made both porters and stouts, but the beers they fashioned were drier and more acidic. For the first time, there were two distinct varieties of porters and stouts—the brown-malt English ales, and those in Dublin that were made without it.

Back in England, porters continued to dominate the London market through the 1850s—they had now been king for over a century—but milds were beginning to cut into their popularity. At this point, different styles were beginning to emerge. Thanks to the increasing prevalence of “stout porters,” regular porters were beginning to get weaker. Toward the end of the 1800s, the government ended a ban on brewing sugar and some English stouts went sweet, creating yet another line in a now-expanding family of dark ales. England now had beers called porter, stout porter, and sweet stout—all slightly different.

The Great Porter Flood of 1814. Industrial-scale brewing led, inevitably, to industrial-scale accidents. Eventually, the ever-expanding porter breweries began to move away from butts and to larger wooden tanks. Over time, these grew, too, into vats containing hundreds of barrels of beer. The vats at one porter brewery, Meux’s, were titanic in size. The largest were seventy feet in diameter and contained 18,000 barrels of porter valued at £40,000 (over £2 million in today’s currency).

On the fateful afternoon of October 17, 1814, an iron hoop slipped off one of Meux’s smaller vats (a mere 22-footer with a capacity of 3,555 barrels). This wasn’t entirely unusual, and the storehouse clerk prepared a note to inform the owners. Unfortunately for the people of Tottenham Court Road, the vat was big enough, and the weight inside—571 tons—heavy enough to overwhelm the remaining hoops and groaning staves. The vat exploded.

The gout of porter contained enough force to create a chain reaction; other vats gave way, and a torrent smashed through the brewery’s brick walls and out into the neighborhood. The rushing porter destroyed homes and killed eight people as it swamped the neighborhood in a fifteen-foot wave of destruction. There was actually a tiny bit of luck in the disaster—if it had occurred an hour later, when people had returned home from the workday, the death count might have been even higher. But the victims surely didn’t consider themselves lucky. One survivor wrote about the incident, “Whole dwellings were literally riddled by the flood; numbers were killed; and from among the crowds which filled the narrow passages in every direction came the groans of sufferers.” Two centuries on, the thought of a wave of ale so powerful it could smash houses is almost hard to believe. But that’s the volume of beer the London porter makers were aging around town.

At about that same time, breweries began to treat porters badly. Some porters grew weaker to compete with milds, and most breweries, in an effort to save money, no longer aged them. Instead, unscrupulous brewers dumped in chemical coloring agents. In some cases, they were little more than stronger milds, and breweries were even borrowing the mild-brewing technique of using dark sugars to color their porters. As a result, by the 1890s, once-mighty porters occupied only a third of the London market. This was a precipitous fall for a style that had so long dominated other beers—and which had, as recently as thirty years earlier, controlled 75 percent of the market.

Still, porters hung on through the ravages of World War I and were still being brewed in the 1940s—but only just. They made it through World War II, but not for long after; by the 1950s, porters—once the style most identified with English brewing—were no longer brewed in England. They survived a bit longer in Ireland, but by the 1970s died out there, too. Porter had become an obscure style, brewed only in remote pockets of the world (including, surprisingly, a few examples in Canada and the U.S.) and was nearly a footnote in the annals of brewing—until microbreweries in the U.K. and North America revived the style in the 1980s.

The word “stout” is, like the names of so many British styles, an adjective. And as an adjective it was used to describe beers long before it became associated with any particular style. To pubgoers of the 1700s, the word meant “strong,” and could be added as a descriptor to any style. Naturally, “stout” was used to describe strong porters, too—but as porter gained such a dominant hold over the London market, the word “stout” slowly became associated with porters. The London breweries helped the trend along, using it to describe their beer (“stout porter” or “brown stout”—both the same product). By the turn of the nineteenth century, the association started to stick, and within three or four decades, it would erase the idea that “stout” might have once been used to describe anything other than porter.

The stout porter of 1800 was, however, not a distinct style. Porters were brewed at different strengths, but the recipes were the same. In England, this was true even after the invention of black malt. Brewing logs of porter brewers Whitbread and Truman show that the grists for porters and stout were identical or nearly so—the stouts were just stronger.

Across the Irish Sea, changes were afoot. The invention of black malt didn’t radically alter London porters and stouts—brewers just added in a pinch of the black stuff to their grists of pale and brown malt. Meanwhile, Dublin breweries abandoned the brown. Their beer was made largely of pale malt with around 8 percent black malt for color and taste. Combined with Dublin’s soft water, the resulting beer was dry and sharp. Like their English counterparts, Irish brewers continued to make porter (called “plain” by locals) and stout, but stout grew in popularity. By the 1840s, more than 80 percent of Guinness’s rapidly growing capacity was comprised of stout—though much was shipped to England, where it was regarded as a different product from local stouts. Ireland’s thirst for porters and stouts was such that it could support three large breweries: Guinness in Dublin, and Beamish and Murphy’s in Cork.

Imperial Stout. Certain beers have romantic histories, and none more so than the beers commissioned in the 1780s by Catherine the Great, empress of all Russia. This was during a period when London breweries were shipping porter around the world, and surely there were excellent examples arriving in Boston Harbor, too. Indeed, five times as much porter was shipped to North America as to the Baltic region. But Boston lacked a monarch, and whatever porters made it that far are long forgotten. The ones sent to the czarina’s court have become legend.

The Baltic trade was very important to the brewers of England, one first exploited by makers of Burton ale (see page 22). London’s porter breweries entered the market sometime in the second half of the eighteenth century, and the Russian connection was in place by the time Catherine came to power. Porters were brewed strong, and stout porters stronger still; the ones sent to Russia were purported to be the very strongest. Since the very start, writers have suggested that strength was needed for the journey, but that seems unlikely. The cool temperatures and relatively short distance would have been perfect conditions to ship beer. Rather, the Russians got strong beer because they liked their beer strong. The Burton ales sent before stout were strong, and the stouts were, too.

The word “imperial” was intended to signal the recipient of the stout, but it had an undisguised double meaning. These stouts—gorgeous, huge aged beers—were not only fit for royalty; they had become royalty. Long after the association with the czars lapsed, the word “imperial” came to denote the beer’s status. Other beers have tried to co-opt this meaning. Imperial IPAs are in regular rotation, but I’ve seen everything from imperial pilsners to imperial hefeweizens (a stunning debacle). Yet in their power and authority, imperial stouts maintain their status as the kings of beers.

Back in England, a curious phenomenon was emerging. Toward the end of the century, stouts were developing an association with wholesomeness and healthfulness. Although breweries were happy to encourage this belief, they don’t appear to have initiated it. In a stroke of luck for the breweries, doctors and scientists were the ones who believed stout was good for health. Stout had long been drunk with shellfish, for which it’s a delicious partner, and was believed to aid in digestion. Perhaps that’s why doctors started recommending stout as a way to restore lost appetite. In an effort to help the trend along, breweries began to bolster their claims by adding ingredients deemed especially salubrious. Two varieties thus created are familiar to today’s drinkers: milk stout and oatmeal stout. Milk stouts were not actually made with milk, just lactose (milk sugar). Yeast can’t consume lactose, so it gives beer a silky texture and adds a bit of sweetness. Oatmeal has a similar effect, adding texture—more creamy than silky—and a hint of flavor and sweetness. Breweries happily cited doctors as they claimed great powers for their milk and oatmeal stouts. They encouraged mothers to drink stout (“nursing stout”), recommended it for women in general (“ladies’ stout”), and of course, prescribed it for the unwell (“invalids’ stout”).

Others are more obscure, like oyster stout, which sounds like a minor abomination. Londoners had already discovered the sublime pairing of the Thames’s most famous bivalve with stout—brewers cut out the middleman and threw the oysters straight in the kettle. Oyster stouts have enjoyed a minor revival in the twenty-first century and, against all odds, they’re actually pretty tasty. The oysters add salinity, but nothing fishy. Oyster stouts have a tinge of brine, but otherwise taste just like stout.

A hefty-looking bottle of McIntyre & Townsend Invalids Stout, brewed in New Brunswick, Canada.

Mercer’s Meat Stout. Of all the stout brewers in Britain between 1880 and World War I, none took the notion of “nourishing” more literally than a small Lancashire outfit called Mercer’s. Their stout recipe doesn’t survive, but the label and a clipping from 1888 tell enough of the story. “nourishing stout,” read the label, “brewed with the addition of specially prepared meat extract. Highly recommended for invalids. refreshing and invigorating.” Mercer’s even took out space in a newspaper advertisement to include medical documentation. Quoting a chemist’s analysis, the brewery boasted that their stout contained “more dry solids than any other stout to be had.” Dry solids—there’s a phrase you don’t see breweries using to tout their beers anymore. Especially meat solids.

From the onset of this phenomenon to World War I, stouts may have taken a cue from P. T. Barnum in their sales pitch, but they were only waxing the apple. The brewery Vaux quoted from The Lancet, the prestigious British medical journal, which had observed, “As is well known, Stout appears to be easier of digestion than beer.” Stout was served in hospitals and even prescribed to patients by doctors.

One company—Guinness—capitalized on this belief and rode it to become the world’s largest stout brewery. It had already enjoyed explosive growth at the end of the century, and World War I, which devastated both breweries and beer gravities in Britain, gored the Dublin brewery less lethally. In 1929, the brewery launched one of the most successful ad campaigns in history based on the catch phrase “Guinness is good for you.” The tag appeared on iconic ads with colorful cartoon drawings for the next forty years. The ads featured different themes, but underscored the brand—in an age before people even understood the concept of branding: “Guinness for Strength,” “My Goodness, My Guinness,” and “A Lovely Day for a Guinness.”

Why Do the Bubbles Go Down? A pint of Guinness is more than a beer—it’s a ritual. As the publican slowly pulls a pint, the black of the beer and the tan of the head course into the glass in one frothy whole. Slowly, magically, the head begins to separate—but as the tiny, nitrogenated bubbles move toward the surface, they simultaneously appear to cascade down the inside of the glass. It’s an amazing optical illusion. What gives?

Scientists have been no less fascinated by a pint of Guinness than we punters, but they have better explanations. Several things are happening. Most beer is carbonated naturally or force-carbonated with CO2. Back in the 1950s, Guinness started experimenting with nitrogen carbonation. In regular beer, carbon dioxide bubbles continue to absorb more CO2 as they float to the surface, becoming larger and more buoyant. Nitrogen doesn’t dissolve as well in liquid, so the bubbles stay tiny—and less buoyant than carbon dioxide.

Inside a glass of Guinness, the liquid is circulating. At the edges, the bubbles touching the glass suffer drag; but at the center, where there is nothing to restrict them, the bubbles rush toward the surface. In doing so, they push liquid up in front of them; when that liquid nears the surface and has nowhere to go, it spreads out and begins to flow downward around the walls of the glass, pushing the not-so-buoyant nitrogen bubbles with it. Those bubbles touching the glass aren’t able to resist the force of downward-rushing beer, and they get shoved along until the cycle carries them toward the center of the glass—and back upward. Of course, in a black pint of Guinness, you can only see the outside bubbles, which makes the illusion complete.

Back in the United Kingdom, the world wars crippled stouts, which were eventually brewed weaker than prewar porters. Yet stouts didn’t just lose gravity; they began to change into something very different from what was shipped to St. Petersburg more than a century earlier. They were not only weak, but, thanks to the shift in the market toward women and sick people, they became overtly sweet. Although this helped them retain their popularity, it was a mixed blessing. Brewers continued to target women, trying to lure them with ever sweeter and milder stouts. Eventually stouts came to be associated with elderly women, which further hastened their decline.

Unlike porters, however, stouts never died out in Britain. This was no doubt helped by Guinness, which opened a brewery in England—among other countries around the world where it opened yet more breweries to serve the local markets. When the craft brewing revolution arrived in Europe and North America, stouts were one of the early success stories, and their popularity has remained intact. Stout is now one of the most admired styles among American connoisseurs. And, like their ancestors, the most admired stouts are the huge, wood-aged ales. After a long period of decline, stout has come full circle. ■

One of many examples of Guinness’s iconic advertising

IT IS NOT UNREASONABLE for certain notions to afflict one’s understanding about porters and stouts: Stouts are heartier than porters, more roasty, thicker. These observations, however true once, no longer match the existing spectrum. Irish stouts, though roasty, are weaker and thinner than most commercial examples of porter. Baltic porters, on the other hand, are stronger than most porters and stouts, and they, too, can be roasty. Sweet stouts are usually in the middle, and at the best only mildly roasty, while export and imperial stouts are big or bigger and have varying levels of roastiness. Beyond the general categories of porter and stout, you may find the names modified by any other number of adjectives as well: milk, oatmeal, maple, barrel-aged, coffee, molasses, cream, licorice, chocolate, sweet, dry, double, imperial. Are porters innately distinct from stouts? Are all these things separate styles?

Let’s start with styles first. The difficulty is distinguishing between real and semantic differences on the one hand and, on the other, the brewing methods. Imagine Porter-Stout were not a continuum of beer styles, but a long-lived car company. Like that car company, over the years Porter-Stout has issued a long list of substyles, some no more enduring or loved than the Edsel. And yet, like those few Edsels still sighted on American roads, many of those funky old porters and stouts still get brewed from time to time. To make sense of things, people have collapsed the various permutations into smaller substyles numbering as many as ten or as few as three or four. To fully capture what are in fact fairly distinct styles, five is ideal: porter, Baltic porter, Irish stout (dry and export), sweet stout, and imperial stout. Each of these is distinct, and together they give a good sense of the full range.

As to the ingredients and flavors, this is trickier business. Breweries regularly modify the names of their porters and stouts, sometimes referring to an ingredient, sometimes to a quality. Chocolate stouts, for instance, often do not contain chocolate. Milk stouts usually contain the sugar of milk, lactose, but no actual milk. Other names may hint at ingredients with general adjectives—“sweet” stouts may include sugar, for example, and “dry” stouts probably include unmalted roasted barley. A word like licorice or molasses? Your guess is as good as mine. Unlike many other styles, though, at least the language of porters and stouts is direct. If a stout is called cream, it will taste creamy; if a porter is called dry, it will taste dry. Whether there’s chocolate in a chocolate stout or not, it will taste chocolatey.

After pale ales and IPAs, porters may be the most abundant style in the U.S., with more than 1,000 commercial examples. There is something essential about these beers, an inherent “porterness,” even when their flavors vary in striking ways. Take the example of two porters from opposite coasts: Deschutes Black Butte Porter from Oregon and Geary’s London Porter from Maine.

Black Butte is so smooth and chocolatey that Deschutes founder Gary Fish quickly realized it was the perfect entry beer for novices. When people at his pub requested the lightest beer he had, he offered them a deal. “‘I’ll get you that beer, but taste this first.’ We figured about 80 percent of them said, ‘Oh, that’s really good, I’ll have one of those.’” The dark malts are martialed primarily for their caramel and chocolate elements, but a gentle roastiness rounds out the sweetness and adds balance.

For his porter, David Geary wanted to inspire the memory of the great porter heyday in London. He consulted a recipe from 1805 in creating his deep, roasty beer undergirded by caramel and molasses. It’s long and roast-bitter, and Industrial Age words like “oil” and “creosote” spring to mind. (When I mentioned creosote to Geary, he shuddered, but I offer it as metaphor.) Amazingly, Geary’s is the smaller of the two beers (4.2% ABV to Black Butte’s 5.2%)—but the flavor rolls across the tongue like a freight train. If I owned a pub, I would definitely not offer this to the person requesting a light beer—yet it may be the best porter brewed in the world.

Baltic porters—commonly brewed in the Baltic states, Scandinavia, Poland, and Russia—bear some similarity to imperial stouts: Made with black malts and, often, roasted barley, these porters are strong (up to 10% alcohol) and hearty. Yet most are brewed with lager yeasts and have a lighter, cleaner palate, with burnished flavors that tend more toward schwarzbiers than regular, ale-made porter.

Baltic porters have a bitter, roasty quality that can produce flavors of licorice and molasses, and sometimes even a ryelike sour. Because they’re lagered, they have little in the way of esters, and the malt provides minimal sweetness—yet they’re also very smooth and silky. In some you might find a sherry-like dry note; in others you find a plummier port note. They are purpose-built to address the long, dark, cold winters of the north. Many niche beer styles have lost market position because they’re timid or a little boring. Baltic porters are neither—they’re obscure because of the historical anomaly of the Cold War, and only now are they becoming better known to those who lost track of them while they remained on the other side of the Iron Curtain. They are one of the hidden treasures of the beer world—but perhaps not for much longer.

For most people in the world, the word “stout” applies to one beer: Guinness. In the long period of decline among the porters and stouts of England, Irish companies established their product as the stout. Beamish and Murphy’s, the two breweries of Cork, may not have achieved Guinness’s fame, but for over a century and a half, they’ve helped Dublin’s giant establish the dry stout (sometimes called Irish stout) as one of the world’s most durable and popular beers.

The standard product of these breweries is a paradoxical brew. On the one hand, it’s very thin and weak (about 4% ABV), no stronger than American light beer. On the other, it is brewed with acrid roasted barley and truckloads of hops, making it a sharp, bitter pour. And speaking of pour, the nitrogen that made Guinness famous livens most Irish stouts, abroad and in the U.S. (Trust Irish scientists to invent a nitrogenating “widget” that ensures each bottle and can results in a proper pint.)

The Counting House, a modern-day tourist attraction in the city of Cork, which used to serve as the face of the original Beamish and Crawford Brewery

An entirely different Irish stout is sometimes honored with its own category designation, yet the entire “style” is really defined by just a single brand. Few beers are as justifiably legendary as Guinness Foreign Extra Stout (“FES” to devotees), and few taste so vividly of the past. Guinness introduced this beer to the U.S. in 1817, though the recipe was different then. Typical of the era, the brewery aged some of its beer in large wooden vats and then blended a portion back into freshly made stout. Like London porters of old, that aged portion was inoculated with wild yeast and bacteria and grew acid over time. This was FES, and although the recipe has evolved thanks to the invention of black malts and the later inclusion of unmalted roast barley, it retained its character thanks to the huge vats still in use as late as the 1990s. The writer Michael Jackson visited then, reporting that aged, soured beer was still being blended in FES. The “lactic, winy” flavors came from “a blend of beers, one of which has been matured for up to three months in wooden tuns that are at least 100 years old.”

Curiously, Guinness is now hugely secretive about its process. When I spoke to master brewer Fergal Murray, he wouldn’t even acknowledge those lactic, winy flavors anymore. “Do you think it has those?” he asked coyly. He acknowledged that the pH was lower because of the roast barley, and “maybe these things are giving you, or the people out there in the world, that perception.” Tours are no longer given, even to journalists, and the company speaks only in general terms about their process, invoking the “unique mystery of Guinness.” He elaborated on that mystery, sort of. “There is a special brew that is separated in the brewery and goes via a variation in process times in brewhouse and in fermentation—which we use to enhance the flavor characteristics of Guinness. More taste. Only known to a few.”

Guinness’s great vats

Whatever the process, the result is one of the most intense beers on the market: a muscular 7.5% stout of great density and layered complexity. The black malts are charred and ashy, as bitter as French roast coffee but also tannic and dry. They would overwhelm the beer were it not for a latent acidity, which reins in the malt astringency and allows FES’s quieter flavors to emerge—chocolate, dark bread, grassy hopping.

What qualifies as a sweet stout? The category is admittedly something of a catchall, encompassing all those lowto midstrength, sweet-side stouts, including many of the “adjective stouts”: milk, oatmeal, maple, cream, and chocolate. The “sweet” in the name is suggestive of more than just flavor; these beers often feature an elevated proportion of unfermented sugars and dextrins. Beyond the perception of sweetness, this lends a sense of creaminess and smoothness. Many sweet stouts have a mild roasted note for balance. In fact, despite their name, some may not even be particularly sweet. Rather, their mildness and smoothness are merely relative.

Thanks to the success of Samuel Smith Oatmeal Stout, a beer released for the first time in 1980, oaty stouts have become a familiar subtype. Oats have an oily, silky quality that provides body and flavor, perfect in this style. Until recently, milk stouts were a rarity, but they have found a voice in many of the examples produced throughout the U.S.—particularly in the South. Milk stouts have a richness that comes from unfermentable milk sugar (lactose). “Cream” stouts, a related variation, may or may not have lactose; the name often just refers to their quality, not ingredients. In the same way, “chocolate” may refer to an ingredient (Young’s Double Chocolate Stout) or the blend of malts alone (Brooklyn Black Chocolate Stout). Whatever their source of smoothness and sugar, sweet stouts are toothsome, surprising alternatives to their bitter, roasty kindred.

If beer were dessert, imperial stouts would be chocolate mousse. Strong beers are innately rich, but imperial stouts, with their heady combination of booze and dense, syrupy malts, are the kings of decadence. Breweries treat them like desserts, too: This is no beer for understatement, and brewers do everything they can to max out the flavor, density, thickness, and strength. Beer drinkers, much like chocoholics, return the love: Imperial stouts are regularly rated the highest among all beers by both fans and critics.

What makes them so beguiling is not just their strength. Barley wines and some Belgian styles are equally musclebound. But unlike those beers, imperial stouts have a secret weapon: dark malts. Pale malts by themselves are sweet, and in strong beers, this quality can cloy. The ways to offset that are few. Dark malts, on the other hand, contribute their own bitterness as well as a roasted or charred flavor. The very thing that makes some high-gravity beers sweet is what helps balance an imperial stout. The result is liquid dark chocolate—intense flavors stripped of excessive sweetness. Roastiness is the tentpole, but underneath the big top, an imperial stout may have an array of dark fruit, coffee, and port or sherry flavors. ■

THE ARCHITECTURE OF modern porters and stouts is similar, if counterintuitive. Both styles rely on pale malts (80 percent or more), which provide the convertible malt sugars and enzymes critical for fermentation. Everything that distinguishes porter and stouts—the color and flavors—comes from the remaining fifth of the grist. Yet that minority portion is where all the action is, and the possible variations mean that no two recipes will be exactly the same.

The key building blocks for black ales are crystal malt, chocolate malt, black malt, and roasted barley. Crystal malts add sweetness and a caramel note but will also inflect black malts, producing flavors of red fruit and cocoa. Chocolate and black malts are both roasted to varying degrees of color—think mediumand dark-roast coffee. Despite its name, chocolate malt can have a harsh, dry quality—it pairs well in grists with sweeter crystal malt. Black malt has a deeply roasted, burned bitter quality, and is so intense it’s never used in more than a few percentage points of the total grist.

Finally, one of the key ingredients in Irish stout is roasted, unmalted barley, but it wasn’t always so. It was only sometime in the late 1920s or ’30s that Guinness started adding roasted barley to give its stout more flavor. The Guinness we know today is influenced heavily by that change; roasted barley imparts a dry, astringent, coffee-like bitterness. It’s the taste of Irish stout—but not the ancient taste.

To add depth and complexity, brewers may add small portions of specialty malts. Common ingredients include rye, for its earthy, spicy note; wheat, to improve head retention; oats, for body and silkiness; smoked malt, for flavor; and sugars (including brewing sugar, honey, molasses, and maple syrup), either to reduce body and add alcohol or to add color and flavor. Stouts and porters provide excellent foundations for flavored beers—they’re hearty enough that fruits and spices add character without overwhelming. In recent years, coffee, vanilla, cocoa, fruit (cherries are a favorite), and chile peppers have become relatively common. ■

FOR A CATEGORY of styles as broad, historical, and occasionally weird as porters and stouts, “evolution” looks more like recycling. Many of the recent trends are a return to the old ways or variations on old themes. After decades of steel-conditioning, wood barrel–aging has returned to fashion in brewing, and imperial stouts are one of the most common barrel-aged beers. The modern version of this process began in the 1990s in the U.S., where bourbon barrels are readily available (by law, distilleries can only use them for one batch of whiskey). Most breweries have great success with these limited-run stouts, and in some cases, as with Deschutes The Abyss, Three Floyds Dark Lord, Portsmouth Kate the Great, and Firestone Walker Parabola, they sell out as fast as Super Bowl tickets.

Americans didn’t own the barrelaged stout market for long. European breweries got in on the act—but of course, they used barrels from whisky distillers closer at hand. (Though it’s worth noting that many Scottish distillers also use those cast-off American bourbon barrels, too.) This isn’t limited to Scottish breweries—the Netherland’s De Molen ages Hemel & Aarde (“Heaven and Earth”) in barrels from Bruichladdich, on Islay, and breweries in Denmark and Norway also use Scotch barrels—but Scottish breweries seem to have made the most of it. Extreme beer king BrewDog ages its imperial stouts in a continuously rotating series of whisky barrels, while Harviestoun Brewery works solely with Highland Park for its Ola Dubh (“Black Oil”)—a beer the brewery calls an old ale.

Beer aged in these barrels pulls not only vanilla oak tannins from the wood, but also the whisky, which is instantly evident on the nose. Bourbon adds a sweet, boozy note, while Scotch gives stouts an elegant, smoky touch.

The risks of barrel-aging: Some casks harbor wild yeasts or bacteria or allow in too much oxygen, spoiling the beer. One in every few dozen barrels may be lost.

Until about 2005, it was rare to find flavored stouts and porters, but now it is at least as common to find them flavored as not. Often this means subtle additives that blend in with the dark roasted malts, like coffee, cacao, or licorice (an ancient porter ingredient), but increasingly, fruit stouts, herb stouts, and other flavored stouts are easily available, especially at brewpubs. An especially interesting trend is the return of oyster stouts. Whole freshly shucked bivalves go into the kettle, and then brewers add the shells to the conditioning tank. Perhaps the first modern oyster stout was made in Dublin in the 1990s by the craft brewery Porterhouse. In the U.S., Harpoon and Flying Dog have offered recent examples, but the City by the Bay seems to have claimed the style for its own. Its Magnolia Gastropub and Brewery brewed a version in 2008 and 21st Amendment followed. Just up the road in Petaluma, HenHouse has also gotten a piece of the action. ■

PORTERS AND STOUTS are among the most varied styles available. It would exaggerate the point to say no two are alike, but not by much. The flavors that dark malts produce, which can range from milk chocolate sweet to charcoal bitter, offer breweries incredible range. The beers mentioned here are a representative sample of this diversity, but they could be matched by two or three times as many equally good sets of beers. If you like dark ales, you could make a life’s work of trying them all—and what a nice life that would be.

Take note, also, that imperial stouts are among the best beers to age (and indeed, many need to be aged; some breweries are adopting “best after” dates). As their character evolves, harsh burnt or hop notes will soften and eventually vanish. In time, those port and sherry notes, along with fruit and chocolate, will begin to replace the rough edges. If the stout was sharp-elbowed in its youth, in maturity it will develop into a round, resonant beer.

LOCATION: Bend, OR

MALT: Pale, caramel, chocolate, wheat

HOPS: Cascade, Bravo, Tettnang

5.2% ABV, 1.056 SP. GR., 30 IBU

A good way to get a sense of the range of this style is to compare Black Butte with either Geary’s or Anchor porters. Black Butte is one of the most purely pleasurable beers on the market. It has a light-bodied but complex malt base of chocolate and caramel sweetness, with notes of nuts and a trace of roastiness. When people used to think of dark beer, they imagined heavy, aggressive, bitter beers; with Black Butte they get just the opposite.

LOCATION: San Francisco, CA

MALT: Pale, caramel, chocolate, black

HOPS: Northern Brewer

5.6% ABV

Anchor Porter, dating to 1972, isn’t America’s oldest—that honor goes to the version Yuengling introduced in 1829. But it’s certainly the oldest craft-brewed example, and remains one of the most characterful. Unlike Deschutes Black Butte, Anchor Porter is dense and rich, pouring into the glass like espresso with a long, sustained head. There’s some coffee in the palate as well, but also a bitter roasted barley note that recalls Baltic porters. A perfect accompaniment for a bowl of chowder or plate of oysters.

LOCATION: Portland, ME

MALT: Pale, crystal, chocolate, black

HOPS: Cascade, Willamette, Golding

4.2% ABV, 1.045 SP. GR.

David Geary has produced a beer that is not only a worthy homage to historic examples, but one that evokes Victorian Britain with its smoky, black palate. It is a lush, velvety beer with a long intensity that belies its modest strength. It is yet a step further away from Anchor and Black Butte—the Islay single malt of porters.

LOCATION: London, England

MALT: Pale, crystal, chocolate, brown

HOPS: Fuggle

5.4% ABV, 37 IBU

It’s wonderful that there’s a traditional London brewery making porter again—even if porter has a ways to go before it can be considered rehabilitated. Fuller’s is a great start, with an intensity of dark, roasted flavors that belie its strength. There’s a bit of bready roundness underneath that softens the beer just a touch.

LOCATION: Żywiec, Poland

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

9.5% ABV

Żywiec Porter vents an earthy and slightly sour aroma, one with a subtle molasses note. The vibrant flavor follows suit, with a cascade of bitter, roasted malts with the quality of coffee, molasses, and very dark chocolate. Some beers are so bitter that they start to come back around toward sour, and that’s the case with Żywiec. Yet, amazingly, it’s a smooth, silky beer that also lends itself to large, greedy swallows.

LOCATION: Riga, Latvia

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

6.8% ABV

The recipe for this Latvian porter goes back to the early twentieth century. Although it has roastiness that’s characteristic of the Baltic porters, it is the one of the smoothest and sweetest examples available. The palate produces interesting flavor notes: Beyond roastiness is a touch of licorice and a flavor that sometimes invokes beets, at other times cola.

LOCATION: Brzesko, Poland

MALT: Pale, caramel, Munich, roast

HOPS: Undisclosed

8.3% ABV, 1.092 SP. GR., 38 IBU

Compared to Żywiec and Aldaris, Okocim is a meatier beer—though still smooth and elegant. Of all the Baltics, Okocim is the most balanced and approachable. It has a touch of roast but is largely characterized by a raisin-sweet body and silky texture.

LOCATION: Dublin, Ireland

MALT: Pale, caramel, black, flaked barley, roasted barley

HOPS: Galena, Nugget, East Kent Golding

4.2% ABV

This 1990s vintage brewery is happy to claim the mantle of authenticity, and this beer is its calling card. It is heartily charred and if you hold your head one way you’ll taste dark cocoa, but maduro cigar the other. A beer that’s happy to invite comparisons with Dublin’s more famous dark ale.

LOCATION: Cork, Ireland

MALT: Pale, wheat, roasted barley

HOPS: Undisclosed

4.1% ABV

There are three traditional draft Irish stouts dating back to previous centuries—Murphy’s, Guinness, and Beamish. All three have long since homogenized so that they appear identical in their graceful tulip pint glasses, topped by a luxurious meringue-like head. Each is different and has its bloc of fans, but of the three, Beamish has the most character. Wheat provides body the others lack, and the palate is deeper and more burnt. Beamish is the hardest of the three stouts to find, which only increases its allure.

LOCATION: Dublin, Ireland

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

7.5% ABV

For those used to standard draft Guinness, FES is a shock. It is a huge beer, and rough and thick as a stevedore’s neck. I find it ashy in its char, and the body does nothing to smooth things. Halfway through the bottle, subtleties emerge, like caramel and rye bread (or is it pumpernickel?). It will change the way you think about Guinness.

LOCATION: Dublin, Ireland

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

6% ABV

Many people don’t realize this beer exists, or if they do, mistake it for the Guinness they get on draft. Long before Foreign Extra came to the U.S., Extra could be found in squat bottles on grocery shelves. To my palate, this is the best of Guinness’s offerings by far. It has a thick body, like FES, but is balanced more by a lactic tang than charcoal—vinous and complex. At 6%, one shouldn’t drink it like a session ale, but I’ll admit I have done so.

LOCATION: Longmont, CO

MALT: Pale two-row, caramel, Munich, roasted barley, flaked oats, flaked barley, chocolate

HOPS: Magnum, U.S. Golding

6% ABV, 1.065 SP. GR., 25 IBU

Sold in both regular and nitrogenated bottles, Left Hand is one of the only milk stouts produced in America. With tons of silky body and a rich mocha head, the beer starts sweet and creamy and evolves as licorice, coffee, and a hint of hop bitterness fill out the palate. It’s decadent without being too heavy or saccharine.

LOCATION: Lancaster, PA

MALT: Pale, caramel, chocolate, black, roasted barley

HOPS: Cascade, Golding

OTHER: Lactose

5.3% ABV, 1.053 SP. GR., 22 IBU

Many milk stouts lack malt bitterness, but Lancaster has a nice foundation, with a thick lushness that belies its size. At the front end, it’s all scorched stoutiness, but it softens toward the finish, turning from a dry to a sweet stout in the space of a swallow.

LOCATION: Bedford, England

MALT: Pale, caramel, chocolate

HOPS: Fuggle, Golding

OTHER: Dark chocolate, chocolate essence, sugar

5.2% ABV

Looking at the list of ingredients, you might think Young’s is cheating by trotting out an alcoholic chocolate malted masquerading as a beer. It’s a bit of a close call, for there are some deliciously treat-like qualities in the beer: a creamy, luscious head that may well be hiding a dollop of ice cream, and a bright rubyblack beer that is saturated in cocoa flavor. But then you notice the hints of roast, grain, and even a touch of those delicate English hops. It’s a dessert-y beer, but it’s a beer nonetheless.

LOCATION: Newport, OR

MALT: Pale, caramel, chocolate, roasted barley, Dare malt (proprietary), oats

HOPS: Revolution, Rebel (proprietary)

6.1% ABV, 1.061 SP. GR., 69 IBU

Shakespeare Stout picks up some of its sweetness from the oats, which, when combined with the dark malts, give the beer a chocolate chip cookie wholesomeness. But there’s also a density and bitterness at the beer’s center that keeps it from being, strictly speaking, a sweet stout.

LOCATION: Farmville, NC

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

5.7% ABV

In the best examples, the “milk” in milk stout inspires associations of farm-fresh wholesomeness. Duck-Rabbit’s brew, frothy as latte foam, does this in spades. The flavor is latte-like as well, with perhaps a dash of mocha to round things out.

LOCATION: Tadcaster, England

MALT: Pale, roast malt, roasted barley, oats

HOPS: Undisclosed

OTHER: Cane sugar

5.0% ABV, 1.052 SP. GR., 30 IBU

This venerable stout inspired many an American brewer, but it’s not an easy trick to duplicate it. Smith’s dessert-like stout has the velvet texture of oats but there’s a stiff backbone that comes from the mineral-rich well water.

LOCATION: Kerava, Finland

MALT: Pilsner, Munich, brown, caramel

HOPS: Saaz

7.2% ABV, 1.070 SP. GR., 45 IBU

The brewery produced porter as early as the 1860s, and this recipe has been in production since 1957. Brewed with an ale strain purportedly hustled out of England in a test tube, this ostensibly Baltic porter has much more in common with imperial stouts. It is as thick as maple syrup, and a curl of acrid bitterness rises from its surface. The burnt malt is intense and gives the beer a slightly acid quality reminiscent of Guinness Foreign Extra Stout. A lovely, chewy, dense beer that is surely a tonic to the long Finnish winters.

LOCATION: Fort Bragg, CA

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

9% ABV, 75 IBU

Rasputin is a true titan, a beer in which each element is at the extreme of intensity, but remarkably, it holds together. The blackness of the beer swallows light and the body is stiff enough to float a quarter—that’s how it seems, anyway. Rasputin is pure roast with just an ember of molasses sweetness in the middle and a core of alcohol warmth to balance things out. A beer for Siberian winters.

LOCATION: Fort Bragg, CA

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

9.5% ABV, 75 IBU

If Rasputin is a beer to respect and perhaps fear, Yeti is a more cuddly giant. Black and roasted it is, but Yeti has a sweeter caramel filling than Rasputin—sometimes it even seems to have vanilla as well. Great Divide has expanded the line, which now includes oak-aged, chocolate, and espresso Yetis.

LOCATION: Paso Robles, CA

MALT: Maris Otter, Munich, caramel, chocolate, roasted barley, oats

HOPS: Zeus, Hallertauer

13% ABV, 82 IBU

The roast and liquor vapors hammer into your mouth like a fist, but if you pay attention, you can taste the breadiness of the base malts in this beer. Bourbon marries perfectly with roast in imperial stouts, especially here, when caramel malts help turn it from vanilla to praline. Ultimately, though, it’s those base malts that make this a real standout.

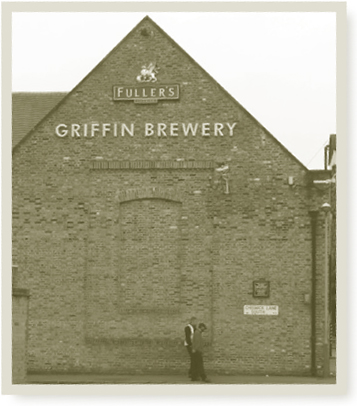

THE BREWERY IN CHISWICK, WEST LONDON, NOW HOME TO FULLER’S, IS SO OLD IT STILL BEARS THE NAME OF A PREVIOUS OWNER: GRIFFIN. CLIMBING UP ONE OF ITS WALLS IS THE OLDEST WISTERIA VINE IN ENGLAND, AND OUT FRONT IS A PUB THAT’S EVEN OLDER THAN THE BREWERY. RATTLING OFF A LIST OF SUPERLATIVES LIKE THIS IS NOT UNCOMMON WHEN CITING ONE BUILDING OR ANOTHER—INCLUDING, IT SEEMS, BREWERIES. BUT THOUGH VICTORIAN-ERA BREWERIES LIKE FULLER’S CAN STILL BE FOUND SCATTERED AROUND THE COUNTRY, THEY ARE INCREASINGLY RARE, LIKE SURVIVORS OF A NATURAL DISASTER.

In a sense, they are. Over the space of a generation, Britons abandoned hundreds of years of drinking habits, giving up their local cask ales for fizzy lager. Carnage resulted. From the 1970s onward, scores of England’s famous old breweries vanished. Those that hung on were confronted by a very difficult decision. In order to appeal to changing tastes, should they continue brewing their well-known line of beers with the same traditional methods? Or should they overhaul their breweries and brands and risk extinguishing the very product they were trying to save?

The Griffin Brewery name acknowledges the long history of brewing at this site—at least 350 years back, well before Fuller’s acquired the land in 1845.

Breweries didn’t all make the same decision. Greene King (founded 1799), the U.K.’s largest producer of traditional ale, went with tradition. The company invested millions of pounds into the old tower brewery, but not to modernize it. Instead, they refurbished their old equipment. “We could have gone mash-filter, we could have gone lauter, but no: We said we’re staying with what we know,” head brewer John Bexon told me. It has survived by purchasing the brands of smaller breweries on the edge of bankruptcy and brewing them at its plant at Bury St Edmunds. Adnams (founded 1872) instead tacked directly into the wind, completely replacing its current brewery with a state-of-the-art, eco-friendly German system. It turns itself on at four-thirty in the morning and can brew any style of beer to exacting specifications—including precise washes for the distillery that Adnams installed in 2010. “When it came to work production,” Jonathan Adnams, chairman of the family-run board, said, “we had a very different thesis, which was about going to the cutting edge of technology.”

An interior view of the new brewhouse

The brewery’s wisteria vines are the oldest in the country, dating back two hundred years.

Fuller’s (founded 1845) split the difference. In the 1960s and ’70s, Fuller’s was like other breweries: a traditional regional operation using a system that dated to 1883. “Fuller’s was really a company not going anywhere—like a lot of regional breweries in the U.K.,” head brewer John Keeling explained. “The seventies come and it’s still just really pottering along; not really thinking about the future.” Two younger members of the family, Anthony Fuller and Michael Turner, joined the board at that time and set it on a new course. They invested heavily to replace the old brewery with a modern, stainless-steel system. Very slowly, they began expanding their line. They reintroduced London Porter, an evocation of a style once synonymous with the city. Over time they added a specialty line that included beers well outside the English mainstream—1845 (6.3% ABV), celebrating the brewery’s 150th anniversary; Vintage Ale (8.5%), a bottle-conditioned old ale; and more recent experiments like Wild River (4.5%), which is brewed with American hops.

Four Elements of Good Beer.

“On one side of the equation you have to have quality and consistency and that is balanced on the other side of the equation by flavor and character. There are breweries that specialize in producing high-quality, very consistent beer—companies like Budweiser and Carlsberg and Heineken. But maybe they forgot about the other side of the equation, which is to have some flavor and some character. Then there are some craft brewers who really go over the top on character and flavor. You can buy a pint of their beer and think, ‘This is a wonderful pint.’ But if you buy it again a week later, you might say, ‘Well, it’s not the same; I don’t recognize it as that beer.’”

—JOHN KEELING

But front and center in Fuller’s line are three beers—ESB, London Pride, and Chiswick Bitter—that are made by that most traditional, and now almost completely extinct, method: the parti-gyle. This system dates back hundreds of years and was a key feature in London porter brewing in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The way it works is this: Fuller’s makes a mash of largely pale malt with a small portion of crystal malt. Then it begins running the wort into two coppers, first filling one, then the other. The first runnings from a mash are much richer in sugars, and as sparging continues, the wort becomes weaker and weaker. Brewers then collect two coppers of different-strength wort (“gyles”). They use the same hops, but in proportions equal to the strengths of each wort. Finally, brewers ferment the beer out and have two strengths of the same beer. With these as building blocks, they blend the two in different proportions to arrive at four different beers—the three mentioned earlier as well as the burly 8.5% Golden Pride.

“Modern equipment makes the best beer,” Keeling says. But old methods also make exceptional beers. Fuller’s parti-gyle system has achieved something no other brewery in Britain has managed: Each of their three standard cask ales has won Champion Beer of Britain—ESB three times, London Pride in 1978, and Chiswick Bitter in 1989. Those accomplishments followed Fuller’s overhaul of the brewery. It’s no coincidence that since Keeling arrived in 1981, the production at Fuller’s has tripled, from 70,000 barrels to 220,000.

The two masters of Fuller’s beer: Derek Prentice (left) and John Keeling

The brewery itself has become a metaphor for the Fuller’s philosophy; when the company bought new equipment, it kept all the old coppers, tuns, and squares. Now both old and new stand side by side and a tour of Fuller’s becomes a lesson in the lineage of English brewing.