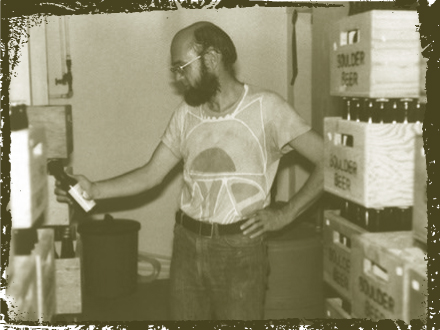

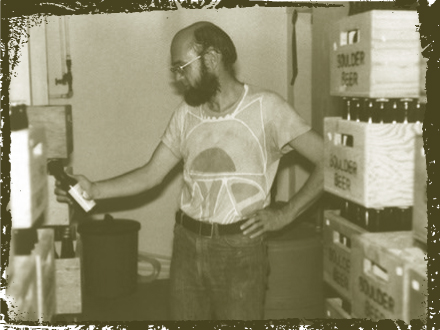

Small-batch brewing started in places like Boulder, CO—Boulder Brewing (shown here) was one pioneer—and Chico, CA.

The existence of “American ales” has for decades been the subject of dispute. In broad outlines, the beers in this family conform to the styles of Britain. Take a random brewery (and especially a brewpub) in the U.S. and you’re likely to find a golden ale, a pale, an IPA, a brown, a porter, and a stout; all are based on English styles. “Show me,” say the proponents of one side of the argument, “any American ale: It’s just an American-brewed English ale.”

There’s an appealing cleanliness to this argument, no doubt. In a Venn diagram of ales, the American and British circles intersect heavily. There remains a problem, though, and I will offer you London’s The Kernel Brewery as an example. The Kernel currently offers several pale ales and IPAs—but no milds or bitters. The pale ales weigh in at over 5% ABV and the IPAs begin at 6.1% and range up toward double digits. All feature classic Pacific Northwest hop varieties; all are bracingly bitter. For good measure, The Kernel offers a massive 9% ABV Red Rye Ale, smoldering with hop heat. In London, no one considers these English beers—they’re purely American.

Americans were certainly inspired by the ales of Britain, and for a time, even tried to brew them. Americans are not good about preserving cultural traditions, though; we inevitably begin changing things, adding a bit more of something here, a bit less of something there. It’s how we ended up with Tex-Mex cuisine and American Chinese food. Within a few years of the first craft-brewed ales, American brewers started adding more caramel malts and hops to their beers, and three decades later, though they still borrow the British names, Americans have created their own tradition. ■

AMERICAN ALES GO way back … to 1976. That is, ales with a character we could call uniquely American. The history of ales in America is a bit older: 400 years. Those older ones arrived with English and Dutch settlers in the seventeenth century, partly to stave off scurvy and dysentery on the long sea journeys, partly because the idea of leaving Europe without beer would have seemed as preposterous as leaving without food. The new colonists found that barley didn’t grow well in their new home, and substitutes—potatoes, molasses—made only provisionally acceptable beer. The colonies were consequently a big target for English exports, which sustained the colonists until a few pockets of brewing finally did emerge. Pennsylvania, where locals felt their porter was a rival to London’s, was one, but an even more impressive hub was Albany, New York.

The town was not only home to dozens of breweries from colonial times through Prohibition, but also to a style of double or XX beer known as “Albany Ale.” It was a huge, Burton-esque beer (see page 22) of more than 8% alcohol, heavily hopped but also sweet. Albany was able to bring in hops and barley from the western part of the state and ship beer out via the Erie Canal, giving it a monopoly on distribution as far west as Chicago and, following the Hudson south, to New York City. Riding the popularity of this giant, Albany became the center of American brewing. In the 1850s there were twenty breweries in town, including the nation’s largest, John Taylor and Sons, which had a capacity of 200,000 barrels annually (enormous for the time).

Still, beer was a small market, and one firmly rooted in the British tradition. As the generations rolled along and the nostalgia for a proper English pint waned, American-born drinkers took to New World libations—rum and whiskey—which they guzzled by the gallon. By the time of the American Revolution, there were 100 distilleries for every brewery in the country. Ale had had nearly two centuries to beguile Americans, but whiskey was the beverage that won the nation’s heart.

Beer reentered the national consciousness in the 1840s and ’50s when German immigrants started arriving by the hundreds of thousands. They brought with them a sophisticated sense of brewing, an entrepreneurial zeal, and very tasty beer. At first, German brewers brewed their dark dunkel lagers for German immigrants, but soon they had learned of a kind of beer that was sweeping through Europe—light-colored, Champagne-beautiful pilsner. Even though there was a big enough market to support Albany’s many brewers, Americans had never really fallen for heavy ales the way they did for liquor. But these effervescent lagers were something else. German brewers began to convert drinkers, and by the time of Prohibition they had largely turned the United States into lager country.

We could jump from the death of ales straight to the birth of craft brewing when ales reenter the picture, but it would deprive us of the heart of the story. The evolution of the beer market following Prohibition until the 1970s is the reason craft brewing happened in the first place—and also why ales were at its center.

After Prohibition, the remaining American beer companies went on a decades-long period of consolidation. They waged a constant war against each other to gobble up market share, all in the service of making and distributing beer more cheaply. With great size came more efficient breweries, more streamlined distribution networks, and bigger profits. Since the founding of the country, breweries had been regional businesses; with consolidation came the national brewery.

For the first time in history, the market seemed to favor consolidation over choice. Even as local breweries disappeared, along with local brands and sometimes quirky local products, consumption rose. By the end of the 1970s, breweries had largely been gobbled up and the U.S. had fewer than fifty brewing companies—the lowest number since before nationhood, and down from about 700 following Prohibition—all while sales rose.

By historical standards, this was bizarre. In beer-drinking cultures across the continents and millennia, it was far more common for multiple styles of beer to be brewed. Even if you go all the way back to Egypt and Sumer, you find a variety of styles. Yet here was the U.S. with one of the freest market systems in world history and for the most part it revolved around just a single style of beer.

Into this strange void stepped the first of the craft breweries in the 1970s. They were all tiny and woefully undercapitalized. Banks wouldn’t touch them (when Redhook cofounder Gordon Bowker was looking for financial backing, one prospect told him, “Breweries don’t start up, they shut down”). Metal fabricators didn’t know how to make the tiny breweries they needed, and malt and hop wholesalers dealt on a scale an order of magnitude larger than the first “microbreweries”—as they were known then. The kind of people drawn to craft brewing weren’t businesspeople and they didn’t think of themselves as competitors with Budweiser. They were more like pirates launching periodic raids on the empire of bland beer, trying to spice things up. Their currency was hand-crafted brews, an artisanal product that had the quality of a philosophical statement of purpose; they were the anti-industrialists.

An Indigenous American Style. Until the 1980s, the U.S. was variously credited as having contributed very little to the world’s brewing traditions or as having significantly harmed them. Neither is correct. In the nineteenth century, Americans were at the forefront of brewing innovation, and what emerged from the mash tuns in St. Louis and Milwaukee was both original and exceptional. Subsequent events harmed the beers’ reputation and buried their memory—and left us with a false sense of America’s place in brewing. Those early lagers deserve more credit than that.

When the first German brewers began setting up shop in the U.S., they made the beers they were trained to make back home—dark lagers that were easy enough to brew with American barley. The beers were heavy, though, and American drinkers found them overly rich. To accommodate local tastes, breweries began experimenting with corn, which lightened the body without reducing alcohol content. The experiments were qualified successes—breweries found they could reduce beer’s body with lighter grains, but corn was oily and hard to work with, and more than a few batches ended up dumped into the rivers.

The use of corn might have died out were it not for the arrival of pilsner, which had begun spreading across Europe. Americans wanted to brew the style, too, but local six-row barley was a rough, high-protein strain incapable of producing the clarion golden beers of Bohemia. Barley couldn’t produce them alone, anyway. But blended with white corn or, especially, rice, it could. It took years of development and tinkering, but in the end, led by St. Louis’s Anheuser Brewing, American brewers figured out how to make beautiful, pale sparkling lagers. The beers were so good that Anheuser Brewing won the grand prize in a European competition in France in 1878 against German, Bohemian, Austrian, and Bavarian lagers.

Good beer fans sneeringly dismiss this so-called adjunct beer as an affront to the art of brewing. The term is meant to connote not just a type of beer but a moral failing. They think of adjuncts like corn and rice as fillers, used only to stretch a buck and dilute a beer. The use of adjuncts necessarily makes a beer worse, less beery.

But when breweries began using corn and rice in the mid-nineteenth century, the grains cost more than barley. They were hard to figure out and more complicated to work with. Breweries began using them not to cut corners or appeal to less sophisticated tastes, but because they yielded better beer. It was only much later that the use of adjuncts served the purpose of stretching a buck—and those ingredients were only one factor in the degradation of American beer. Originally, adjuncts were a triumph of brewing, and Budweiser really was the king of beers.

“Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.” Ben Franklin’s famous (mis)quote is well known to beery types, and can be seen on about half the T-shirts at any given beer festival. It seems a satisfying verification of the things we know about Franklin and beer: Ben was a bit of a libertine, but a Founding Father whose love of beer seems to vouch for its patriotic purity. Unfortunately, it’s also a crock: Franklin never said it. Worse, it’s the misappropriation of a quote from a 1779 letter in which Franklin extols … brace yourself … wine.

“Behold the rain which descends from heaven upon our vineyards; there it enters the roots of the vines, to be changed into wine; a constant proof that God loves us, and loves to see us happy.”

How French is that? (Franklin was, of course, a Francophile, one of the many reasons some red-blooded Americans hold him at some distance.) Turns out the fake quote was brewed up by the United States Brewing Association after Prohibition. As a part of their protracted campaign against liquor producers, they worked tirelessly to link beer to the Founding Fathers, patriotism, and, presumably, moms everywhere. Or possibly it came much later, when a clothes manufacturer put the quote on a T-shirt. Tinkering with the legacy of a Founding Father to make a buck? How American is that?

Ales were the obvious choice for the insurrection. Many early craft brewers had visited Britain and were delighted by the rich, characterful beers they found there. Most had a background in homebrewing and knew it was possible to turn out a great ale in a couple weeks’ time instead of the month or more it would take to make a lager. But mostly, they wanted to offer a sharp contrast to the impenetrable wall of impersonal, factory-made, pasteurized light lagers found at pubs and groceries.

Sierra Nevada founder Ken Grossman identified the two prongs of attack: “The craft brewers from early on wanted to do something different [that] also … really had some flavor impact.” American industrial brewers aimed to produce exceptionally mild beers that evoked German lagers, with noble hops and a very light character. The early microbreweries raised the Jolly Roger and went for styles that not only offered a contrast, but tweaked the macros. They brewed ales; absolutely rejected corn, rice, and sugar—but not wheat; and proudly used the strongly tangy American hops the national brands eschewed. The first craft beers were different and, compared to every other available beer, packed a flavor punch.

It’s a little bit hard to imagine, but by the 1980s most Americans had lost all sense of beer styles. They knew beer to be one thing—mild, light lager. For the first microbreweries, this presented an interesting challenge: simultaneously trying to educate and entice new customers. Yet since customers had no basis for judgment, they didn’t know themselves what would be enticing. The first fifteen years of craft brewing was a period of testing as breweries cast about, trying to hit on the beers that would strike a chord.

For some breweries, this meant making beer that had at least some connection to light lagers. In San Francisco, Fritz Maytag had launched Anchor on its now-famous Steam beer—a close cousin to lager. Other West Coast breweries made pale ales (Sierra Nevada, Hale’s) or golden ales (Full Sail). In regions with intact brewing traditions, like Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, early craft breweries like Capital, Sprecher, and Penn all started with lagers. Still others set out in different directions: Widmer Brothers thought German altbier would be a winner, so they brought a culture of yeast back from Düsseldorf to make the city’s signature beer in Oregon. In Maine, David Geary built the first English-style brewery, complete with open fermenters and a traditional yeast strain.

Craft breweries launched many beers in the 1980s, and many were failures. The Widmers’ altbier, a rich copper beer with a stiff dose of hops, was too aggressive for its time. Boulder Brewing Company (called Rockies Brewing for a while before settling, ultimately, on Boulder Beer) continued to tinker with its line from its founding in 1979 until it settled on its current crop in 2002. In Kansas City, Missouri, Boulevard Brewing was initially known for Bully! Porter and other English-style ales. Ultimately, the swaying Midwestern wheat fields suggested a different course and Unfiltered Wheat became not only Boulevard’s flag-ship, but one of the bestselling beers in the Midwest. These were the lucky ones. Many breweries from the first fifteen years of the American craft movement didn’t survive early failures and have vanished from memory.

Small-batch brewing started in places like Boulder, CO—Boulder Brewing (shown here) was one pioneer—and Chico, CA.

By the early 1990s, a few trends had emerged. British-style ales were selling well in the U.S. and customers were becoming familiar with that manner of brewing. But in addition to standard British-style beers, Americans were also making things that seemed British—but weren’t. Starting with golden ale (the lightest and the ale stand-in for Budweiser), a brewery would offer increasingly dark beers: pale, amber, red, brown, porter, stout. Americans jettisoned the mild ale—usually a dark, weak beer—and invented a range that went from light to dark and weak to strong. It wasn’t the way British beer worked, but it made sense to American consumers learning a whole new style of brewing.

This is an important deviation that set America on its journey to indigenous style. In Britain, each of the beer types had emerged from its own set of circumstances and entered a very mature market made up of preexisting beers; styles waxed and waned as trends and preferences swept through the market over the course of centuries. But in America, customers had no context for the ales microbreweries were offering. They had no more idea where a pale ale came from than a stout or a brown. The idea of a spectrum of beers, which ranged from lighter to darker, had an obvious logic—new drinkers could sample from the range and locate themselves on it. This meant two things. One, the whole range now had a relational quality. There was a coherence to the progression, a stylistic unity that ran through the beers. It was so pronounced that it produced a second phenomenon, the two middle colors—amber and red—that didn’t exist in Britain. To fill out the line, American breweries essentially invented these styles.

The standard ale range didn’t represent the whole of early American craft brewing. A parallel development was happening with wheat ales. American breweries were loath to use adjunct grains like rice and corn in their lighter beers, but wheat seemed as natural, wholesome, and artisanal as barley. It had the bonus of producing a soft, crisp beer that didn’t shock those coming to craft brewing from regular beer.

“People didn’t know anything about craft-brewed beers. Everybody had to be educated about what style it was—about what style meant—even what an ale was versus a lager. The distributors didn’t know anything about it—they were just used to selling Rainier or Blitz or whatever else was on their truck. Customers knew even less than that.”

—KARL OCKERT, brewmaster of Bridgeport Brewing Company, founded in 1984

Like many others, the trend got started on the West Coast. Anchor was the first brewery to make a wheat beer in 1983. It wasn’t a big departure from the other ales American breweries were making—Anchor just used a sizable portion of wheat in the grist to make a light, golden wheat ale. After the Widmer Brothers Altbier got off to a slow start, they introduced an unfiltered wheat ale that became one of the first real hits in the Pacific Northwest. Across the Columbia River, Hart Brewing (now Pyramid) was having similar success with a straight wheat ale and one made with apricots. By the early 1990s, Midwestern breweries were offering similar examples, and it was there, in America’s bread-basket, that the style really flourished. Over time, Bell’s (Oberon), Three Floyds (Gumballhead), Goose Island (312 Urban Wheat), and Boulevard (Unfiltered Wheat) saw more and more of their production devoted to wheat ales. Taken together, they represent a substantial chunk of the American craft market.

Throughout the first decade of craft brewing, the industry grew at a steady, hopeful clip. Bit by bit, brewery by brewery, Americans were being introduced to new styles of beer. By 1990, there were more than 200 craft breweries, and they were turning out an impressive range of beers. Then came the gold rush—a massive explosion in the number of breweries—and with it, a period of serious style confusion.

The first generation of craft brewers had only wanted to brew good beer, but it was clear that microbreweries offered a real financial opportunity. A number of early breweries were flourishing, and some were getting quite large. Boston Beer Company led the way, passing a half-million barrels by 1994. Pete’s Brewing and Sierra Nevada both crossed the 100,000-barrel mark by 1995.

Their success created a craft brewery bubble when speculators started flooding the market. The number of breweries more than doubled between 1990 and 1995 and then doubled again by 1997. Entrepreneurs rushed in without trying to understand either the craft of brewing or the market for beer. By the mid-1990s, grocery store coolers were awash with treacly fruit ales, insipid goldens, and light pale ales, as well as beers riddled with quality issues. For a time, customers were so excited about craft beer that they were willing to try anything—including the bad ones. In a parallel development, some companies were catering to the nonbeer market, those who liked wine coolers and sugary flavored “alco-pops” like Zima. They were trying to cash in on the microbrewing trend, and their products further diluted the market. There were a shocking 1,376 breweries by 1998—a sevenfold increase in eight years—and many were making terrible beer.

Casualties of the revolution: Chicago Brewing, Indianapolis Brewing, and Jefferson State

Conversely, many breweries had entered the market determined not to condescend to their customers. Bert Grant, one of the pioneers, launched his brand in 1982 with a stunningly aggressive 45 IBU Scottish Ale (at just 4.7% ABV, it was surely the hoppiest beer in America). Sierra’s Ken Grossman debuted with a beer that still sets the standard for American pales. Bell’s, Summit, Pyramid, Redhook, Boston Beer, Catamount, Penn, and Stoudts all founded breweries making rich, flavorful beers. But by the late 1990s, these products competed against a confusing mess of knock-offs and wannabes. The interlopers used the same homey labels and professed the same level of devotion to artisanal brewing, but their beer was watery or worse. Unlike the pioneers, many of these breweries were well capitalized and could afford to dump huge money into distribution and marketing—but often neglected the beer and breweries.

Then the inevitable happened: Customers started walking away from craft brewing, leading to the collapse of hundreds of breweries. In 1999, the number of craft breweries declined by 17 percent and sales stagnated. Consumers weren’t tired of the fad, but they were souring on bad beers. Breweries changed their brands like designers changed the latest fashions. Buying a six-pack of beer became a roll of the dice. Breweries selling gimmicky beers watched their fickle customer base vanish —sometimes with devastating results.

Although the future seemed gloomy at the time, this was a pivotal moment for American brewing. When the smoke cleared, what remained were the avid drinkers. They had been slowly developing their taste for the bold flavors of beer—working their way up the spectrum ladder—and by the early 2000s, the market turned decisively toward those types of beer: stronger and hoppier.

In California, Stone Brewing was a leader in superhopped beers, along with Lagunitas and Bear Republic. In the Pacific Northwest, BridgePort’s 1996 launch of IPA fundamentally reoriented brewing toward beers made with saturated hop flavors and aromas. The Midwest featured maltier, more balanced versions that were also deeply influential, like Bell’s Two Hearted Ale and Three Floyds Alpha King. On the East Coast, IPAs that split the difference between English and American interpretations also had a large effect on the market—Harpoon IPA, Victory HopDevil, and Brooklyn East India Pale Ale.

The impact may not have been immediately evident in the sales figures (and in fact, it would take a decade for these examples to surface as top-selling beers). Yet the evidence was there. Entries into the annual Great American Beer Festival illustrate the waxing and waning of popular styles. In 1999, as craft breweries were just finding their voice, ninety-five breweries entered beers in the amber ale category—a favorite in craft brewing’s first decade. By 2010, only eighty-three breweries entered amber ales. Conversely, in 1999, 118 beers were entered into the hoppy India Pale Ale category; by 2010, that number had jumped to 174.

Boulevard’s Steven Pauwels (left) and Deschutes’s Larry Sidor collaborate on a “White IPA.”

This is finally being reflected in the marketplace as well. After years and years at the top of the bestseller list, Boston Lager, Sierra Nevada Pale Ale, and Widmer Hefeweizen are all having to share shelf space. The fastest-growing segment is IPAs, fueled by brands like Sierra Nevada Torpedo, Stone IPA, and Lagunitas IPA. In 2012, IPAs had captured 18 percent of the craft market—well ahead of the number two, pale ales, which claim just 11.5 percent of the market. By the end of the second fifteen years in craft brewing, big, hoppy, citrusy American ales are leading the way. ■

Contract Brewing. Craft brewing began in part as a philosophical rebellion. To the scale and mechanization of industrial brewing, the first craft brewers offered handmade ripostes. They looked to an older tradition of brewing, where people hauled their own grain sacks and hand-tended cauldrons of bubbling wort. No computer screens, no push-button brewing. Of the few dozen breweries that started up in the first decade of craft brewing, nearly all began by building small-scale breweries to fulfill this vision.

Jim Koch took a different approach. When he founded Boston Beer in 1984, he saw no reason to build a brewery. There were plants all over the country with excess capacity, and his business plan called for a practice known as “contract brewing”—working with existing breweries to make his beer when they weren’t making their own. He partnered with Pittsburgh Brewing Co. to produce Boston Lager and spent his energy selling, not manufacturing. It was a great move: Boston Beer quickly grew to be the largest seller of craft beers, and remains so to this day. As a practice, it took contract brewing a little longer than microbrewing to catch on, but when people realized there was money in good beer, it took off.

But the practice rankled the small brewers who’d spent precious money on steel. Microbrewing’s one advantage was the sense that it was made locally, on a human scale by someone in the back room. Brewers saw themselves as craftsmen, not beer peddlers. Contract brewers—these guys were charlatans trading on the folksy image of microbrewing to reap huge rewards. Maureen Ogle documented this trend in her fantastic history of American brewing, Ambition Brew: To the other craft brewers, contract brewers were “more interested in making a buck” than brewing beer (Kurt Widmer), “a bunch of promoters” (Bert Grant), beer “brokers” (Ken Grossman), and salesmen “in three-piece suits” (David Geary).

In many cases, these criticisms were well deserved; in the early 1990s, contract breweries were turning out a lot of dreck, reflecting poorly on the entire industry. Boston Beer proved it was possible to compete directly with craft breweries, though, and has a roomful of awards and accolades to prove it.

Over time, the image of contract brewing changed. Jim Koch returned to his hometown of Cincinnati and bought the Hudepohl-Schoenling Brewery, one of the sites where Samuel Adams is now brewed. Breweries regularly take on contracts to fill their own production capacity, often for other craft breweries. This helps the contracted brewery’s bottom line, and allows breweries to make beer in far-flung locations, rather than shipping it—which in the age of environmental consciousness has the virtue of being green, as well. It has become a regular practice in the brewing industry, perhaps still slightly stigmatized, but no longer so controversial.

The Ringwood Ales of New England. Beyond a national character, regions within the U.S. have their own quirks and preferences. None has such a specific, single-source culture as Red Sox country. If you travel New England—especially Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire—you’ll find many ales brewed in the English tradition. Bitter is a standard, as are porters and stouts. Cask ale isn’t obscure. Fuggle hops are as common as Cascade. Yet I was surprised, during one of my early visits, to notice a smooth, buttery character in the beers there—particularly the bitters. Not just one example, but one after another.

It turns out there’s a very good reason for this. In the early 1980s, interested in starting his own micro, Mainer David Geary spent time working at breweries across Britain—Samuel Smith in Yorkshire, Belhaven in Scotland, and finally at an important early English craft brewery in Hampshire, called Ringwood. David Austin had brewed for decades at England’s Hull Brewery, and when he started Ringwood in 1978, he brought Hull’s ancient yeast along with him. The strain dates back possibly 150 years, and flourishes in open fermenters from which it produces dry, fruity ales with loads of character. Depending on how it’s used, the yeast also produces diacetyl, that smooth, butter-flavored compound I noted in Maine.

This is how it got there. David Geary decided he liked Austin’s system the best, so he hired Alan Pugsley from Ringwood to come set up the brewery and act as brewer. The system Geary’s uses to this day is very much in the mold of Austin’s brewery—round, open fermenters (Geary calls them “Yorkshire rounds”—a riff on the region’s more famous Yorkshire squares) from which the brewery can skim fresh yeast for subsequent batches.

After helping Geary with his system, Pugsley continued on, the Johnny Appleseed of Ringwood brewing, setting up at least eight more New England–based breweries in less than a decade, including Magic Hat, Sea Dog, and Gritty McDuff’s. David Geary has no tolerance for diacetyl, though, and his beers exhibit not a drop, but this is the exception. Unlike Geary, Pugsley likes a touch of butterscotch, and as a consequence, the later breweries weren’t designed to minimize diacetyl. He established his final brewery in Portland, Maine—Geary’s hometown—in 1994. That was Shipyard, now one of the twenty largest craft breweries in America. His legacy, though, is much more than Shipyard, and the next time you’re north of Boston, stop in for a pint somewhere and see if you can’t find his fingerprints.

CONSERVATIVELY speaking, the roughly 3,000 American breweries produce 40,000 separate styles of beer each year. Every style of beer brewed commercially somewhere in the world is also brewed in the U.S., and American breweries even experiment with revival styles of long-extinct beers. Because the American beer market was so wholly transformed by industrial-scale brewing, it lost a sense of a national tradition. Craft breweries have therefore felt unfettered freedom to brew any beer they have heard of or can imagine. It’s safe to say that no country has ever produced the variety of beer currently available in the U.S.

That is not to say that there isn’t a distinctive American tradition in brewing. There is. As American brewing evolved, it began to acquire the characteristics that now define it—and which can be seen across styles and traditions. Americans brew for intensity, a penchant reflected particularly in high hop rates and alcohol strength, but more broadly in ales that are just a bit louder than comparable ales brewed in other countries. This means tart ales are more puckery; roasty ales are a bit more acrid; strong beers are a bit more boozy; and almost all beers are a bit—usually quite a bit—more hoppy.

And hops are, of course, the key to American styles. Where German and British styles have seen a slow slide in terms of bitterness, Americans have been steadily amping up the volume. But this isn’t only a matter of bitterness. Hops are the character around which American ales are built. It starts with American varieties—an ever-expanding landscape of dozens of strains—that boast wild, exotic flavors and aromas. Citrus is the word most associated with these hops, but many strains contribute strong elements of pine, mint, or tropical fruits. (There’s a reference guide to hops and their character in the Appendix.) Some have an herbal character similar to oregano; others, floral notes like lavender or gardenia. Some even suggest bizarre flavors like onion—which a minority of tasters locate in the Summit strain.

American breweries do everything they can to showcase hops. They may use complex and precise hopping schedules—including hopping the mash, adding hops in a hopback on the way to the chiller, or dry-hopping their beer (and sometimes all three)—or deploy baroque combinations of hops. Sometimes they use a single variety to draw out specific notes from the hops, like using a single wine grape. Whatever they do, though, the idea is to make vivid beers that glow with flavor and aroma. This is a general practice not limited to style.

One way of looking at hops’ centrality in American brewing is to look at the styles of beers the thousands of breweries produce. By far the most common are pale ales and India pale ales—the styles most suited to being tricked out by hops. As a testament to how essential this style has become, forty-five of the largest fifty American breweries offer an IPA in their regular lineup. Most also offer a hoppy pale ale. Only two of those offer neither, and one is an all-lager brewery.

After mass-market lagers, pales had been king for two decades in American brewing, but they finally lost their title in 2011 when IPAs eclipsed them at the supermarket. Together, IPAs and pales now constitute nearly four in every ten craft beers sold at supermarkets while ambers, in a distant third place, continue to fall further behind in beer drinkers’ favor.

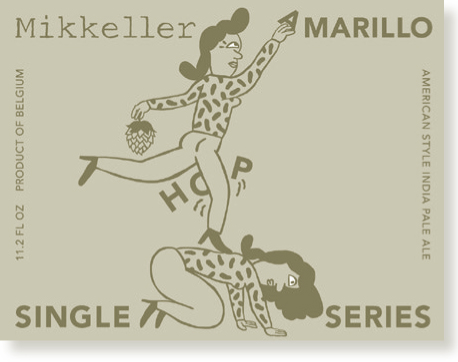

As the country’s brewers have become more and more associated with making ales like this, “American” has become an adjective. And “American ales” are spreading elsewhere. Breweries in Britain, Belgium, Eastern Europe, and Scandinavia now explicitly produce “American-style” ales—as do, of course, hundreds of brewers closer to home.

Mikkeller Single Hop is an American-style IPA brewed in Belgium.

When craft brewing was just finding its sea legs, breweries produced a category of light, inoffensive beers on the theory that they would act as a “gateway” or “crossover” to fuller-flavored beers. Golden ales were the early breweries’ answer to standard light American lagers. Straw-hued and neutral, they had little in the way of character—just a light maltiness, fruity esters, and a kiss of citrusy hopping. Over time, the theory of gateway beers looked more and more dubious, and goldens have slowly been dropping out of beer lines across the country. As the market matures and new drinkers enter with no expectation about what “beer” should taste like, goldens will likely continue to migrate to the margins of craft brewing.

Amber ales almost certainly started life as beers designed in the mold of English bitters. Brewed for balance, early examples were maltier and sweeter than pale ales—an approachable yet robust style for the new craft drinker. James Emmerson, brewmaster for Full Sail, one of the first producers of American amber, acknowledged the source material “was English ESB, certainly.” The word “amber” seemed a less confusing description for the American market, and it allowed breweries to soup up their interpretations. Full Sail Amber was designed with “more American hops, more alcohol, a bit more bitterness than was standard.” Emmerson called it an “American ESB,” and his version would become one of the benchmarks.

Amber ales haven’t changed much since the 1980s. They still feature a balance point tilted toward sweetness. Made with a generous portion of caramel malt, they have a round, sweetish body that harmonizes naturally with citrusy American hopping. Ambers are not brewed for bitterness, but many have layered hop character that, like the architecture of an English bitter, rewards careful attention. Ambers are excellent session beers that seem to reveal more as one drinks—and many, because of their low-intensity flavors and excellent balance, are absolutely ideal for serving on cask.

Canned American Culture. When Americans started making ales, they went right to the British well for source material. Pretty soon, an American idiom developed, and like national traditions everywhere, it has emerged partly by brewer design and partly by customer demand. British drinking culture evolved around the pub. Central to pub drinking is the idea of session beer: low-alcohol beer of easy balance that drinkers can enjoy over the course of hours. Even with the success of packaged beer, British drinkers still consume over half their beer on draft. In the U.S., draft sales have been on a continuous decline for decades and now account for just 10 percent of the market. Instead, Americans drink their beer in front of TV sets, in backyards, at campsites—and mostly out of aluminum cans.

Almost as soon as cans were released, Americans adopted them, and by 1940, we were drinking over half our beer at home. Cans, prized for their portability, have been popular for decades but were for many years eschewed by craft breweries because of their association with mass-market lagers. Beginning in the early 2000s, though, more and more craft breweries bought canning lines—they are cheaper than bottling lines, preserve the beer as well, and have a smaller environmental footprint. Within a few years, consumers realized the virtues of cans, and the stigma of “cheapness” has largely evaporated. At last count, more than 400 breweries canned beer in America, and the number grows by the day.

Red ale is often lumped in with ambers, but it’s an evolving style that has now wandered pretty far from its starting place—and away from ambers. Yet even at the beginning, reds were distinct. While ambers were essentially American interpretations of English bitters, reds were a kind of sui generis American ale.

As evidence, we need only to harken back to 1983 to the ur-red, Mendocino Brewing Red Tail Ale. The inspirations came partly from an old homebrew recipe from founders Michael Laybourn and Norman Franks and partly from the folk song “The Redtail Hawk”—singer-songwriter Kate Wolf’s ode to California. An English bitter wasn’t the touchstone, so there was no need to keep things in check: Red Tail was lighter in body, caramel flavor, and hopping than the early ambers, but it was strong at 6.1% ABV. The beer, now more than thirty years old, seems tame by current standards, but it was a template for much of what would come to characterize American brewing.

The difference between Red Tail and modern reds is the difference in thirty years of craft brewing. As America began to fall in love with hops, reds got hoppier. As bigger beers became more popular, reds became bigger. Modern reds are in some ways the quintessential American beer. Some of the most popular examples are muscle-bound ales—examples north of 7% ABV are common. The color is there mainly to add visual interest, but the malt backbones are stripped bare—just a bit of neutral or candyish sweetness—to reveal the true essence of the style: hops, hops, hops. Because of their strength and focus on hopping, reds are similar to IPAs. Reds, however, are the hophead’s hoppy beer. With no malt noise to interfere with the lupulin assault, they have the quality of hop distillates: pure tinctures of lupulin bitterness and flavor.

Wheat ales were the beers that skipped the bouncers and came in through the back door. To drinkers, they seemed natural enough—light, soft, summery ales that offered a gentle counterpoint to heavier pales. But the traditionalists—the bouncers—fingered them as frauds. European wheat ales are full of quirky fermentation characteristics: Bavarian weizens are phenolic, Berliner weisses tart, and Belgian wits spiced. American wheats had none of this and a few were even adulterated with fruit. The decades have been kind to the style, though, and now they’re welcome to the party.

As it happened, American wheats weren’t failing at being other styles; they were exactly what the early brewers wanted them to be: uncomplicated, sessionable summer ales. Wheat is a grain far more familiar to Americans than barley, and wheat ales are comfortably recognizable. There is a quality of breakfast in a wheat ale—the wholesome grain-y flavor, a light spritz from American hopping, and a gentle, soothing finish. They offer other virtues as well. Wheat ales are a mutable accompaniment to a variety of cuisines. Contrasted with the sweetness of pork, they provide supportive crispness; yet they shift to add a sweetness that contrasts the tartness of a salad’s vinaigrette. Wheat ales make fine bases to tinker with, too. Breweries regularly add fresh fruit, spices, or crisp lactic acids (through sour mashing or the addition of bacteria) in an ever-expanding portfolio of variations on the style. ■

THERE ARE NO hard-and-fast rules in American brewing—but there are a few rules of thumb. One is hopping, of course. (Rule of thumb: use lots.) The other is the use of crystal or caramel malt, a less-discussed but important marker of national character. These malts do two things: First, they create an obvious flavor note—caramel or toffee—that sweetens the beer and inflects the fruity tones of American hops. Second, they are kilned to produce complex sugars indigestible to yeast, which gives beer body and creaminess.

American ambers and reds are similar, but one difference is this contribution of caramel or crystal malt. Ambers rely on crystal for both their color and flavor; they’re heavier and sweeter with the residual sugars of that malt, and their color comes from it. Reds are lighter and drier and have a subdued caramel note—or none at all. Reds get their color from reddish Munich or Vienna malts, or sometimes from a touch of roast malt.

Take, for example, the classic ambers from Full Sail and Anderson Valley. Both have a light caramel aroma and distinctive toffee flavors. In Boont Amber, Anderson Valley uses crystal to combine with spicy hops for a gingerbread effect; Full Sail marries the caramel with the citrus from Cascade hops for a sweet, moreish middle. In contrast, the booming red Tröegs Nugget Nectar goes for the grist of an Oktoberfest—Munich, Vienna, and pilsner malts. These give the beer a bit of support, but mainly throw color; for Tröegs, Nugget Nectar is all about the intensely grape-fruity hopping. Cigar City Tocobaga Red Ale does use a touch of caramel malt in the grist, but the predominant flavors are a hard candy base and a sustained, resinously woody hop note. One version of this beer is aged on cedar, imparting a nuance suggestive of some U.S. hop varieties—and the effect is a magical blending of flavors and expectations.

These could be considered a class more than a style—variations on the theme are acceptable, even welcomed. The basic function is consistent, though: Wheats are light and quenching, softened by the presence of wheat without being oppressed by it. In some parts of the country, that means a very light ale, low in bitterness. Goose Island 312 Urban Wheat is a simple beer, made with standard two-row barley and torrified (puffed) wheat with Liberty and Cascade hops. It is quite light at 4.2% ABV and has just 20 IBU. Boulevard’s Unfiltered Wheat is similar, a 4.4% beer made with a mixture of wheat types, two-row barley, Munich malts, and just 13 IBU of American hops.

Other wheat ales are less demure. Widmer Brothers helped introduce the style of American wheat, and their Hefeweizen, despite all the visual evidence to the contrary, has a lot more in common with pale ales than the Bavarian beer it was named for. The Hef is often served with a slice of lemon, and its yeast billows inside a grist of 43 percent wheat. But the flavor is crisp and spicy with 30 IBU of hopping—and the beer, at 4.9% ABV, is no lightweight. Bell’s Oberon is even stronger, 5.8% ABV, with 26 IBU; Three Floyds Gumballhead is 5.5% ABV and 28 IBU.

Common variants of wheat ales, these are made with fruit. They are brewed in the American vein, a simple wheat ale base flavored with fresh fruit. They aren’t soured or otherwise made more fussy—though their simplicity has a quality that might be considered “rustic” in another country. The style can be delicious, but a flood of overly sweet, soda-like examples in the 1990s nearly doomed it. Brewers learned to ratchet back on the fruit, let the beers dry out, and allow the wheat to emerge. The best examples, like 21st Amendment Hell or High Watermelon and Pyramid Apricot Ale, find that balance. In these beers, the fruit juice has fermented out, leaving behind a harvest-fresh aroma and fruit delicacy. On a balmy summer day, they’re hard to beat. ■

AMERICAN CRAFT BREWING was born of a thirst for variety. Four decades later, the country boasts easily the greatest diversity of beer styles in the world. What the U.S. lacked at the dawn of craft brewing was a national heritage; the first decades were a process of exploration, and slowly the country began to find one. That trend suggests there will be a necessary narrowing of focus in the decades to come. In craft brewing, ales have the overwhelming advantage, and among them, this is especially true of those that are rich with American hop character. Other trends hint that some Belgian styles might be ripe for popularization, and drinkers’ preference for strong flavors has given tart ales an opening. But in the second decade of the twenty-first century, America now has what it lacked in the 1970s: a national tradition, one copied across the globe.

Ambers and wheats are largely static styles. They achieved early success, and nothing freezes a style so well as popularity. Twenty years ago, wheat ales and ambers were session ales—wheats light and easygoing, ambers heartier and more filling. Both remain so today.

Mayflower Ale. Like so many important events in history, beer played a central role even in the fateful journey of the Mayflower. Settlers departed from England in the late summer of 1620 and by the time they sighted land, it was icy November. Despite the cold and storms, those dutiful English subjects didn’t land there—they were observing their agreement to settle on land granted to them by the Virginia Company of London, located farther south. They battled poor weather and rough seas, and were starting to run low on beer. A worried passenger noted the danger in his diary: “We could not now take time for further search, our victuals being so much spent, especially our beer.” After a few days of battling the weather, they decided to drop anchor at what would eventually be called Plymouth. English authorities had given them the right to settle in Virginia—which at the time extended to what is now New York. So to make things legal, the colonists drafted the famous Mayflower Compact to underscore their continued allegiance to God and King and disembarked.

Red ales, on the other hand—never a wildly sought-after style—have been able to grow and change outside the scrutiny of mainstream tastes. Their development looks a great deal like the course of American brewing. In the mid-1990s, Jennifer Trainer Thompson published a book called The Great American Microbrewery Beer Book on the bottled beers of the U.S. (about 120 breweries in all). Only sixteen of the 500-plus beers were American reds (ambers numbered four times as many). They averaged 5.3% ABV, and three-quarters were less than 6%. This was typical for the time. I compared these with the sixteen most-rated red ales on the beer ratings website BeerAdvocate.com. These are the reds most broadly available, so they’re typical for the era. They average 6.6%, range from 5.1 to 9.5%, and only a third are less than 6%. Trainer didn’t track bitterness units, but looking at the IBU of the top few current reds—93, 67, 45, 90—we can assume those have spiked at least as dramatically.

Where American ales still have room to evolve—reds, pales, IPAs, and imperialized styles—they will continue to focus on hops. This doesn’t necessarily mean more bitterness, though. In the past few years, breweries have focused more on hop varietals and hopping techniques designed to produce new, ever-more-distinctive flavors. Sierra Nevada and Widmer were active in bringing Citra hops to market—giving them an early edge on “branding” their beers with the unique flavors they contribute. Other breweries are growing their own hops or supporting development of other strains.

Europeans, once scornful of rudimentary American offerings, are now brewing in the emerging American tradition. In Britain, where tradition is sacred and drinkers are hidebound in their preferences, American brewing has sent out shock waves. New, smaller breweries are popping up all across the country to brew American-type ales, and many, like Thornbridge, Dark Star, and The Kernel, are attracting big audiences for their huge, ultrahoppy ales. The phenomenon is so profound that British hop growers have planted famous American strains there.

Every style has its moment, and American ales will not always be on brewing’s cutting edge; yet the fact that they have gotten there at all amazes anyone who was on the scene in the 1980s. The country has now joined the ranks of the traditions of Britain, Belgium, Germany, and the Czech Republic as a truly original brewing nation. ■

WHILE THERE ARE a few styles unique to the United States, American brewing is more a state of mind. The most quintessentially American beers are the hoppy pales: pale ales, IPAs, and double IPAs, and these are the future of American brewing. But while America’s love for wheat ales has waned somewhat, they remain among the most popular overall. And red ales in particular are a style to watch—they may one day challenge IPAs for America’s heart.

LOCATION: Hood River, OR

MALT: Pale, crystal, chocolate

HOPS: Mt. Hood, Cascade

6.0% ABV, 31 IBU

I believe there’s some dispute about which brewery gets to lay claim as the first amber, but Full Sail gets my vote. It has each of the hallmark qualities: a thick, caramel body with moderate sweetness; a creamy head; and a long, Cascade hops citrus finish. It’s an American strong bitter, and predictably, is even better on cask.

LOCATION: Boonville, CA

MALT: Pale, caramel

HOPS: Columbus, Bravo, Northern Brewer, Mt. Hood

5.8% ABV, 16 IBU

Anderson Valley’s amber is another classic, though it emphasizes malt where Full Sail tilts hopward. Like a nice bière de garde, Boont Amber is silky and rich, the malts communicating warmth through toffee, toast, and grain. The hops don’t so much balance as adorn, adding an herbal delicacy to the malts.

LOCATION: Escondido, CA

MALT: Pale, caramel, black

HOPS: Columbus, Simcoe, Crystal, Amarillo

4.4% ABV, 45 IBU

A number of breweries are known for hops, but few so well as Stone. Many of its beers are punishingly bitter, so I’d like to nominate wee Levitation, the little sister in the family line. She is definitely a spitfire, with Stone’s characteristic snap of bitterness, grapefruit to pine, but it is the rounded malts that suggest English softness, that carry the day—or beer, in this case.

LOCATION: Albuquerque, NM

MALT: Pale, Vienna, caramel

HOPS: Chinook, Cascade, Centennial, Simcoe, Crystal

6.5% ABV

Even though Marble is a relatively new brewery, its Red, a 6.5% bruiser, is a little bit old-school, with a thick caramel malting like you find in ambers. Marble uses it to balance the gale-force hops that blow in with citrus and grapefruit gusts.

LOCATION: Harrisburg, PA

MALT: Pilsner, Vienna, Munich

HOPS: Nugget, Warrior, Tomahawk, Simcoe, Palisade

7.5% ABV, 93 IBU

Tröegs has a reputation for aggressive hopping, and Nugget Nectar is one of the reasons. The Simcoe hops seem to lead a piney, pineapple charge, but it’s a mutable beer, and melon and lychee make appearances as well. The malts have a bit of caramel in them, but not enough to distract from the main event.

LOCATION: Tampa, FL

MALT: Pale, caramel, dark chocolate, Vienna, Munich

HOPS: Vanguard, Simcoe, Willamette, Cascade, Citra

7.2% ABV, 1.070 SP. GR., 68 IBU

Cigar City is another brewery with a reputation for hops, and their Jai Alai IPA has attracted the most attention. I prefer the Tocobaga, the color of a Miami sunset, hot and juicy with tropical guava and satsuma orange. The malts are a good example of a modern red—a bit of sweetness, a note of bread, but really, they’re there for color and balance.

LOCATION: Athens, GA

MALT: Pale, Munich, caramel

HOPS: Warrior, Centennial, Cascade, Ahtanum

8.8% ABV, 1.088 SP. GR., 73 IBU

In a contrast to Tocobaga, Big Hoppy Monster does have a fair amount of malt hoisting up the hops. It’s more burnt sugar than caramel and is used to great effect to offset a powerful bittering addition of hops. The sugars fade to crispness in the swallow, the hops to pepper and pine (there are those Simcoe again), and it does not feel heavy going down.

LOCATION: Kalamazoo, MI

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Saaz

5.8% ABV, 1.057 SP. GR., 26 IBU

Oberon is a force of nature, greeted annually with its own day of celebration. A cloudily luminous light-orange color, it has a mildly citrusy, spicy top note to round out the crisp, cracker-like body. Released at the end of March, well before the summer has actually come to the Wolverine State, it has a bit more alcohol to help battle the lingering chill.

LOCATION: Portland, OR

MALT: Pale, Munich, caramel, wheat

HOPS: Proprietary bittering blend; Willamette, Cascade

4.9% ABV, 1.047 SP. GR., 30 IBU

Appearance is critical to Widmer’s wheat: something like cloudy lemonade topped with a snowy head and—in some restaurants and pubs—a slice of lemon. There’s a certain sleight of hand going on that prepares the mind for the citrus that follows, but the brain deceives. That note comes from the Northwest hops, not the lemon wedge (which, for the sake of the beer, you should toss aside). It has a bready body, but one kept refreshing by its lightness and sprightly carbonation.

LOCATION: Munster, IN

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

5.5% ABV, 28 IBU

To the unobservant drinker, wheat ales can seem to have a lot in common with mass-market lagers. It’s easy enough to make a dent in a six-pack without realizing it. The best examples remain perfectly sessionable, but sneak in subtle character. Gumballhead has a light presentation, but it’s a lively, bright beer. Instead of a bready wheatiness, it opts for lemon zest. The hopping is just present enough that you might mistake it for an extra pale ale in a blind tasting.

LOCATION: Kona, HI

MALT: Pale, wheat

HOPS: Hallertauer

OTHER: Passion fruit puree

5.4% ABV, 1.048 SP. GR., 15 IBU

Kona has developed a knack for using island ingredients to enhance its beers. Coconut dances with malt sweetness in its Koko Brown, and in Wailua Wheat, it’s lilikoi—passion fruit to you mainlanders—that hulas with hops. On its own, lilikoi is an intensely tart citrus-y flavor, along the lines of a lemon. In Wailua Wheat, it adds the citrus character that is so often suggested by American hops. Lilikoi is a surprisingly good counterfeit, but better—hops are citrusy in the way atomized oil is in air freshener, but there’s a juiciness and vividness in Wailua Wheat that lets the tongue know it’s the real deal.

LOCATION: San Francisco, CA

MALT: Pale, white wheat

HOPS: Columbus, Magnum

OTHER: Watermelon puree

4.9% ABV, 17 IBU

Ahazy, lazy beer for a summer’s day. There’s no trick here—it’s just soft wheatiness married to the light flavors of melon that roll nicely into a quenching acidity at the end. It’s not complex or complicated, and that’s just what you want out in the sunshine.

LOCATION: Tempe, AZ

MALT: Pale, pale caramel, white wheat

HOPS: Magnum

OTHER: Peaches

4.2% ABV, 9 IBU

In Arizona, Four Peaks is known for a Scottish ale and an IPA, but on one of those triple-digit midsummer scorchers, what I want is the superbly balanced Arizona Peach. It has an aroma of pure stone fruit and a flavor that actually has as much cracker-crisp malting as it does juicy sweetness. The best fruit ales are not cloying, taking just the essence of the peach and letting the beer carry the day. Four Peaks nails it.

FOR YEARS, I WAS SKEPTICAL THAT THE TERM “AMERICAN BEER” WAS ANYTHING MORE THAN A MARKETING GIMMICK. EVEN WITH THE ARRIVAL OF CRAFT BREWING, AMERICANS HADN’T DONE MUCH TO REINVENT BREWING. THEY MADE PALE ALES AND PILSNERS AND STOUTS—ALL BEERS THAT CAME FROM OTHER COUNTRIES. IT TOOK A TRIP TO EUROPE, PARADOXICALLY, TO CHANGE MY MIND. I WAS STARTLED TO HEAR BREWERS IN BRITAIN, FRANCE, BELGIUM, GERMANY, AND THE CZECH REPUBLIC MENTION HOW AMERICA’S STRONG, HOPPY, AND BARREL-AGED BEERS HAD INFLUENCED THEIR OWN APPROACH TO BREWING. ALL RIGHT THEN: WHAT IS AMERICAN BEER?

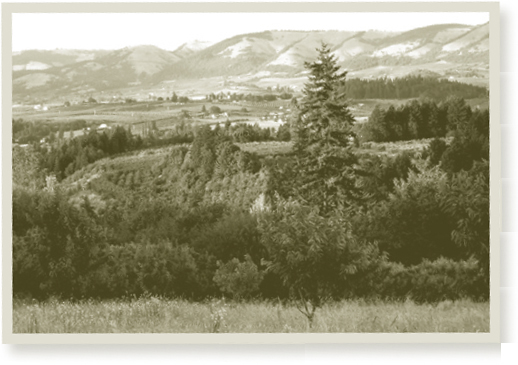

The more I thought about American beer, the more two memories sprang to mind—and they both involved the same brewery, Oregon’s Double Mountain. In the first, the brewery’s cofounder and brewer Matt Swihart was leading me on a stroll through undulating rows of cherry and peach trees on his land near the brewery in Hood River. Each year, Matt makes two types of aged sour cherry beers, and he always uses the harvest from his own land for the key ingredient. It’s beautiful country, and I stood and looked admiringly at the orchards rolling out to the hills in the distance, punctuated by copses of native Douglas fir that soar up over their fruit-bearing neighbors.

Matt Swihart (left) and Charlie Devereux, cofounders of Double Mountain

Double Mountain, like many breweries in the Northwest, has access to locally grown barley and hops, locally malted grain, and even gets locally cultivated yeast. (Wyeast Labs, one of the two main yeast companies in the U.S., is about ten miles away.) It made sense that a brewer from the Hood River valley would use the region’s fruit crops as well. Agriculture and beer have never been far separated, and it’s hard to visualize a kind of local beer that doesn’t depend on the expression of locally grown ingredients. (And of course, pungent, citrusy American hops are the one thing everyone agrees makes our beers distinctive.)

The view from Matt Swihart’s land

The hop back

Fermentation tanks

It’s more than agriculture, though. In places where beer is something more than a commodity, it becomes an idiom understood to locals. This brings me to my second recollection: of arriving at Double Mountain’s pub perhaps a year after the brewery had opened. It was late autumn, already dark at five o’clock, and Hood River’s tourists had long quit the place. Yet Double Mountain was packed. As I looked around, I saw workmen in dirty jeans and flannel shirts crowding around the bar. They were slugging back pints of Swihart’s hazy, aromatic hop infusions. By that time, the brewery had already developed something of a reputation for its IPAs, and it was clear why. It’s what the locals wanted, and they were drinking it by the gallon.

This development was organic, a communication between brewer and drinkers, and is the essence of how native beer comes to be. When Double Mountain opened, it offered a broad range of different beers on tap: pale ale, altbier, kölsch, and strong Belgian ale. Swihart shares my love of pale lagers, and I think he’d be happy making helles biers the rest of his life, but that’s not what people drank. They gravitated to the IPA and the kölsch, which was electrified by generous doses of Perle hops.

Within a few months, Double Mountain added a second IPA called Hop Lava. This was pure West Coast—intensely green and citrusy, with a profound rind-like bitterness that scrapes the plaque right off your teeth. To brew it, Swihart added what he calls a hop back but what is in fact a massive side-tank he packs with whole-flower hops and steeps his beer in until it’s literally green. Not long after, the brewery added another IPA to its regular lineup called Vaporizer, a lighter, less intense beer made with just pilsner malt and Challenger hops. Seven years later, those three IPAs constitute three-quarters of the year-round line (the hoppy kölsch is the fourth).

“Every decision we considered when building the pub or deciding on a yeast, or to filter or not to filter, was to make something that a drinker in Oregon would smile at,” Swihart explained. There’s a notion that skilled brewers, making exceptional, unique beers, drive demand, but it’s exactly backward. When beer culture begins to develop, the drinkers have the final say. Their preferences guide the brewers. The very best, like Matt Swihart, take their direction and then make the exceptional beers that meet those preferences. “If you can deliver a well-made beer, fresh with yeasty aroma and light texture, consistently day after day,” he said, “then your brewery will likely succeed.”

It’s the process that led to cask ale in England and strong Belgian golden ales and dark lagers in Bavaria—very different beers the locals wanted to drink. As the process unfolds, regular drinkers are dictating what “American” means in other parts of the country, as well. Wisconsin’s New Glarus sells lots of lagers and lager-like ales to the descendants of German immigrants. In New England, Shipyard, Portsmouth, and Cambridge make beer quite a bit like they do in old England—which is what locals expect. Fullsteam Brewery, in Durham, NC, is introducing the concept of Southern brewing. They use corn grits, sweet potatoes, persimmon, paw-paw, chestnuts, and more to bring the tradition of Southern cuisine to their beer.

When Europeans talk about American beer, they are pointing to one or more of these aspects that have developed to serve the preferences of different kinds of Americans. Double Mountain makes beer characteristic of the Pacific Northwest. It’s cloudy and rustic, rich with saturated hop flavors and aromas, and generally a little less bitter and a little less strong than some of the California beers that made “West Coast” pale ales and IPAs famous. Double Mountain is often credited with having helped perfect this kind of Northwest beer, but actually, the brewers were only listening to their customers. Double Mountain makes exceptional beer, true. But the key is that it’s Oregon—or American—beer, made the way drinkers want.