French Ales

Pity the poor French brewer, toiling away in a country with legendary wine. Across two borders, his colleagues make beer known and loved throughout the world, yet in his own country his labors routinely go unnoticed. Even among connoisseurs, France is a footnote—home to bière de garde, a minor style, and not much else.

Pity the poor beer drinker, unwittingly cheating herself by overlooking France—currently home to one of the most exuberant beer scenes in the world. It boasts twice as many breweries as neighboring Belgium and has far more on offer than just those bières de garde—which are, with their rich history and French refinement, not just a minor style. Unfettered by local expectations, French breweries are quietly making some very interesting beers, many with spices, wheat, honey—whatever sparks the brewery’s fancy. The spirit of French gastronomie seems to animate these toothsome beers, which deserve more than a footnote in the catalog of great beer styles. ■

ORIGINS

FRANCE AND BELGIUM shared a similar brewing heritage for much of their history. They had general similarities in brewing style, with very long boils, low attenuation, the regular use of wheat, and cooling in cool ships that made them part of one family, distinct from the traditions of Britain and Germany. Beyond the basics, though, brewing was a regional art, and the styles varied from town to town. If you were to travel west from Maastricht in the nineteenth century, you could zigzag your way through Leuven, Mechelen, and Belgian Flanders, finding a different style of beer in each city. Cross the current border and you’d continue finding different styles in Lille and Paris. In the 150 miles separating Holland and Lille, you’d bounce along the trail of dark spelt beer, aged barley beer, light-hued wheat beers, and kettle-scorched brown ales.

When Belgian brewer Georges Lacambre visited France in the 1840s, he was more impressed with the beer he found there than with many of his native beers. He praised the robustly effervescent French ales and compared them favorably to Champagne, which quickly loses its head. In Paris, they mainly brewed strong dark ales, though he noted an emerging style, bière blanche de Paris, that much impressed him. Made with coriander and elderflower, it was a perfect summer ale that “deserve[d] to be mentioned as one of the best known white beers.”

Lacambre identified three major French brewing cities: Lille, Lyon, and Strasbourg. Lille was France’s most famous, where they made a family of styles he compared to the amber uytzets of Belgian Flanders. The vinous, tart beers were renowned throughout the region. Lyon made another amber, poorly attenuated and similar to Lille’s stronger beers but “a bit richer.” And Strasbourg, a city traded back and forth between the French and German empires, made a most intriguing beer that sounded very much like another defunct style, Polish-born Grodziskie. It was made of smoked malts, brewed strong, and “highly hopped and quite bitter” in order to age for up to two years. Writing just a few years after Lacambre, the French scientist Louis Figuier agreed with the Belgian brewer’s rankings of major brewing cities, but added Marseille and Tantonville, west of Strasbourg, to the list.

The popularity of French ales started to change in the twentieth century. Lagers were on the rise, already constituting a quarter of the market, and although Lille was still the center of French brewing, traditional ales were in collapse. British brewing scientist R. E. Evans visited in 1905 and reported back to the Institute of Brewing: “Five years ago, about 50 per cent of the beer consumed was of this nature, but now it probably does not exceed 20 per cent.” Within a decade, the First World War would devastate local country breweries, particularly in the war-torn Nord-Pas-de-Calais region where the ales were most common.

By the time the Second World War ended, French brewing had been reduced by 90 percent from Evans’s time and would ultimately drop to about two dozen breweries. The old styles were mostly vanquished. Where brewing continued, it took the form of low-alcohol lager brewing, tailored to the tastes of industrial workers who wanted refreshing, drinkable beer. Ales were still being made, but they were a tiny, largely undocumented fraction of the market.

The basilica at Notre Dame de Lorette in Ablain-Saint-Nazaire is one of the many World War I memorials in the region.

Wait, What’s the Name of the Brewery? Trying to figure out who brewed a French beer isn’t as obvious as you’d imagine. For reasons no one seems to know, local convention dictates that the beer will have its own brand name separate from the brewery’s name. Ch’ti isn’t the brewery, it’s the beer line—Castelain is the brewery. You’ll see Ch’ti Blonde, Brune, and Tripel, but you’ll also find St. Amand, a non-Ch’ti Castelain product. Of course, to make it perfectly murky, not every brewery does this—La Choulette and Thiriez beers are made by La Choulette and Thiriez. Here’s a cheat sheet for some of the prominent breweries and their labels.

|

BREWERY |

BRAND |

Castelain |

Ch’ti, St. Amand |

Duyck |

Jenlain |

Gayant |

St. Landelin |

Jeanne d’Arc |

Grain d’Orge, Belzebuth |

St. Germain |

Page 24 |

St. Sylvestre |

3 Monts, Gavroche |

Theillier |

La Bavaisienne |

Ales started to make their comeback in the late 1970s, when the students in Lille adopted as their beverage of choice a strange throwback beer from the brewery Duyck called Jenlain Bière de Garde. It was one of those rare, oddball ales, first brewed around 1945, but it wasn’t like any of the prewar bières de garde. Indeed, it bore a much closer resemblance to the bocks that started to replace ales before World War I. It was strong, very smooth and malty, and was lagered. Hops played a minimal role, and unlike Belgian saisons, the yeast character was almost completely absent.

Jenlain’s popularity in the late 1970s created the template for the modern bière de garde, and breweries like La Choulette, Castelain, and St. Sylvestre began making similar versions. Still, the success of these beers was modest and didn’t immediately spark a brewing revival. By the 1990s, breweries were still closing down and the future of French beer was in jeopardy. But then the international wave of craft brewing finally arrived in France, and within a decade brewery openings exploded. There are currently more than 250 breweries, and they brew everything from traditional bières de garde and saisons to English cask ale. The market has reached an experimental phase; the breweries are out in front of their customers and it’s not clear which experiments will find a following and which will fail. It’s a time of transformation in France, and in a decade or two we’ll have a better sense of what French beer really is. ■

DESCRIPTION AND CHARACTERISTICS

WHEN PEOPLE OUTSIDE the country consider French beers, they confine themselves exclusively to a single style brewed in a small region of the country by a handful of breweries that export their beers. Ah, the spoils of early entry. The breweries of Nord-Pas-de-Calais in the north were the first to find an ale style that could sell, and their success in establishing bière de garde put France back on the beer map. The style definitely deserves its reputation—it is an authentic expression of French brewing and one found nowhere else.

Steam wafts from the mash tun at Castelain.

BIÈRE DE GARDE

The North Star in French brewing remains bière de garde. The country’s biggest ale producers all make this style and it has become France’s ambassador to the rest of the beer world. Because of its fame and commercial success, the style has become more and more well defined. Brewers even considered trying to establish a protected category (appellation d’origine contrôlée—much like those used for wine and cheese) for bières de garde, but couldn’t bridge differences in production methods. Still, from a style perspective, there is substantial coherence.

The essence of the style is velvety refinement, a quality achieved more through method than ingredients. Bières de garde are all about malt and alcoholic strength; they tend to be on the sweet side, but never cloy, largely because of loving care in the conditioning tank. The idiomatic phrase de garde refers to the practice of keeping or aging the beer. Before the twentieth century, the souring yeasts and bacteria in these brews needed time to mellow in the barrel. Even though the style has changed dramatically, the name still fits: Taking a cue from the lagers of the intervening decades, bières de garde are now fermented cool to minimize esters and then aged—in modern times, “lagered”—for weeks. The effect is consistent: a burnished, malt-scented beer of surpassing smoothness that is delicate despite its strength.

“My first influence, of course, comes from the local bière de garde. During the seventies, I was a teenager, and the 7% Jenlain amber ale appeared like a revelation, an eye-opener. It had so much more taste and more character than the Stella Artois lagers or other brands our parents used to drink when they were thirsty. Other similar beers, like La Choulette, Bavaisienne [Theillier], or later 3 Monts [St. Sylvestre], were also much appreciated. When I started professional brewing in 1996, I simply decided to brew the beer I wanted to drink (and to sell the rest of it).”

—DANIEL THIRIEZ, BRASSERIE THIRIEZ

Bières de garde may be any color. A light amber (ambrée in French) was traditional, but both blonds and browns (brune) are also common. The aromas and flavors depend on the malt: blonds have the least, with just a hint of bread or cracker; ambers have more toastiness or caramel; and browns a bit of dark fruit, toffee, or bread. Hops may be so light that they are almost undetectable—this was the tradition for many years. While no one will mistake a bière de garde for an IPA, hops have lately been getting a bit more use. In beers like Page 24 Réserve Hildegarde and Thiriez Extra, they give a more floral nose and a lacy peppering on the palate.

Bières de garde are strong beers, usually from 6.5% to 8.5% ABV, but the alcohol is well integrated into the malt body. The watchword is smooth, and that also carries over to the body, which is usually lightened by a small amount of sugar. Despite all the elements that might lead to a cloying palate—high alcohol, sugar, and few hops—bières de garde are balanced by their low attenuation and dry finish.

Two variations on bière de garde are ubiquitous in France—lighter, sometimes wheat-based spring beers and darker, heartier, sometimes spiced winter ales. Releasing spring and winter beers is a tradition dating back to the time when brewing was by necessity a seasonal activity. Spring beers (bières de printemps) were made to cool and refresh during the hot working months while winter or Christmas beers (bières d’hiver or bières de Noël) were designed to warm and comfort during the cold season. The current examples follow this tradition, and a brewery’s cold-weather brew is especially anticipated and celebrated. ■

Daniel Thiriez pours out a glass of his rustic bière de garde.

BREWING NOTES

SINCE THERE ARE so many different styles of beer brewed in France under different conditions and on idiosyncratic equipment, we’ll confine ourselves to a discussion of bière de garde, which has a few particular characteristics. For most of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais brewers, it’s not enough to end up with a satin-smooth, malty strong ale at the end of the process. The process itself is a big part of the style.

The mash and boil are typical. Brewers don’t employ exotic malts—usually just a pale base malt with small amounts of color malts like Munich for appearance. They don’t use crystal malts, which would increase the body, and in fact, many add some sugar to reduce body and help attenuation. This is important in the versions where hops are used at a minimum. There is a growing sense that local ingredients are best (a matter of philosophy more than taste), but some breweries don’t restrict themselves to only the limited number of French hop varieties. French malts, renowned worldwide, contribute a warm, grain-y character—though it is a subtle quality.

A bière de garde’s identity is born in the fermentation tanks. Yeast’s role is to ferment the beer cleanly and then disappear, as in a lager or Scottish ale. Some breweries use lager strains, some use ale, but they all ferment at a temperature chilly enough to inhibit the production of esters and phenols. They lager or “garde” the beer to create the signature smoothness. This is not an optional process or even one breweries consider—it’s just the way one brews. When I asked Brasserie St. Germain’s Stéphane Bogaert about the reasons for garding the beer, he seemed mystified, as if the benefit were self-evident. At first, he didn’t understand the question, and then he walked me through the process again, like I was just a slow learner. Breweries lager their beers for different lengths. Three weeks is the minimum, though a month to six weeks is usual. Castelain ages its beer for a minimum of six weeks and as long as twelve.

The final, mostly normalized process is filtration (another major way in which bière de garde differs from saison). Breweries do this partly because the final product—highly carbonated, cascading from a large bottle—sparkles with the clarity of lager, but some also believe it helps the beers age better, since most are not bottle-conditioned.

The brewers of the region have an almost patriotic sense about the lineage of their beers. Local ingredients are another part of the identity of bière de garde—not mandatory, but definitely part of the flavor. Alain Dhaussy, owner and brewer of La Choulette, believes this was an important part of the style’s reinvention: “Using locally available resources—yeast, specialty malts, hops—small breweries in the Nord have made beers that represent a transition between top-fermented beers of the past and new classic lager beers.” ■

EVOLUTION

IN OTHER PARTS of France, bière de garde is not king. Most of the country’s ale breweries are tiny enterprises. Most don’t distribute much beyond their hometowns, never mind exporting. They are so small that about half don’t even have websites. In the nineteenth century, brewing had distinctive regional differences, and that pattern seems to be emerging again. Away from the gravitational pull of the Nord, they are drawing influences from Britain, the United States, Germany, and Belgium. Collectively, the beers they brew coalesce into some general types—proto styles that may emerge in coming years as further examples of native French brewing.

As when any country experiences a mighty growth spurt, the current French beer scene is experimental, transitional, and unstable. Just as the United States sampled from other traditions during the 1980s and ’90s until its brewers found their voice, France will probably follow suit. You can see signs of American influence in the hoppy ales of hip breweries, like Ninkasi’s IPA (that’s the Ninkasi from Lyon, not Eugene, Oregon) and La Franche’s strangely named XXXYZ Bitter. The old German influence remains strong in places like Strasbourg, where lagers are still king (think Kronenbourg, Meteor, and Fischer).

A café in Wormhout, France, in Nord Département—where bières de garde rule.

Reading a French Label. Most French-language beer labels (including Belgian ones) get a translation before coming to America. But since the vast majority of French beer is not exported, you have to pick up a few bottles when you visit. And on those bottles, everything’s in French. Some words don’t need translation—blonde, ambrée, brune, and bière de Noël are obvious enough. Others terms less so. Here’s a quick reference.

|

avoine |

oats |

bière artisanale |

hand-crafted beer |

bière blanche |

wheat beer (literally “white beer”) |

bio/biologique |

organic |

blé, froment |

wheat |

châtaigne |

chestnut |

coriandre |

coriander |

épeautre |

spelt |

gingembre |

ginger |

haute fermentation |

fermented warm (i.e., ale) |

houblon |

hops |

levure |

yeast |

maïs |

corn |

miel |

honey |

non-filtrée |

unfiltered |

non-pasteurisé |

unpasteurized |

orge |

barley |

refermentée en bouteille |

bottle-conditioned |

sur lie/sur levure |

bottle-conditioned (literally “on the yeast”) |

Other beers are influenced by the U.K., including British-style ales like those made at Merchien (bitter, porter, and IPA) and especially the Bastide Brewery, owned by Englishman William King, which makes only cask ale. In France, Scotland is still remembered fondly for the “Auld Alliance”—the commercial and military agreement between the two countries designed to impede English attacks on either. It may have ended more than 400 years ago, but that doesn’t stop affectionate homages in the form of Scottish-style ales and even a Scottish pub in Paris called The Auld Alliance.

It’s no surprise that the biggest influence is Belgium, as France is its largest export market. Tripels, wits, and rustic ales first entered the market as imports and were popular enough to inspire imitation. Tripels are often linked by name to some local monastic tradition like St. Landelin from Gayant, but that’s not always the case (Castelain Maltesse has only a vaguely ecclesiastical connotation).

Witbiers seem less of an imitation than an inadvertent reproduction: Many breweries make a blanche (wheat beer) and the spicing seems to have occurred naturally to French brewers. Indeed, spicing is more important to French brewing than Belgian. Spices like coriander and orange peel are so common they find their way into not only blanches but bières de garde, spring beers, winter beers—just about any style may have a dash sprinkled in. The French can get far more creative, though. Brasserie du Chadron, inspired by local hemp fields, makes a hemp ale. Brasserie des Abers, makers of the Mutine line, also make a beer with hibiscus and another with seaweed. Rare Courtoise makes farmhouse-y beers with meadowsweet and dandelions. Brasserie du Sornin may have them all beat; their expansive range includes beers made with elderberry, lentils, anise, mushrooms, honey, and chestnut extract.

The latest development is the most interesting—the return of rustic, saison-style ales. Recall that originally, there was no difference between Belgian saisons and French bières de garde. They were both tart, spicy, and rich with whole-grain flavor. As Belgian saisons have become a worldwide phenomenon, they are once again being brewed in the Nord. Brasserie au Baron, literally on the border with Belgium—in fact, just feet away—makes one of the best-known saison-style beers, Cuvée des Jonquilles. Daniel Thiriez has also been sending his beers in a more rustic direction, especially with Extra and La Rouge Flamande.

Sadly, very few of these other beers are available outside France. In order to experience the full range of French brewing expression, you have to visit. (And there you were, just scheming for an excuse to go to France.) ■

THE BEERS TO KNOW

THE FRENCH BREWING renaissance is in such an early stage of gestation that most of the country’s diverse offerings are only accessible with a plane ticket. The beers prepared for export are largely bières de garde from the larger breweries of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais. That’s not a terrible state of affairs; those beers offer a wonderful and unique world to explore.

ST. GERMAIN RÉSERVE HILDEGARDE BLONDE

LOCATION: Aix-Noulette, France

MALT: Pale, Munich

HOPS: Brewer’s Gold, Strisselspalt

6.9% ABV, 1.076 SP. GR., 32 IBU

The beers of St. Germain’s Page 24 line possess a deft softness that in another beer might come from wheat (only its Blanche uses it). The Blonde is smooth but not quite as polished as other bières de garde, perhaps owing to the delicate, herbal hopping. The IBUs belie what is actually a pronounced flavor somewhere halfway between lemon rind and wildflowers.

CASTELAIN CH’TI AMBRÉE

LOCATION: Bénifontaine, France

MALT: Pilsner, amber, crystal

HOPS: Magnum to bitter; undisclosed flavor hops

5.9% ABV, 18 EBU

First brewed in 1983, Ambrée is one of the oldest bières de garde available. Ambers are the most traditional, so this is a taste of one of the first examples of the style. Ch’ti is highly carbonated and effervescent, but this somehow doesn’t dampen its creamy richness. It is a pure malt experience, with no hops evident to the nose or on the tongue.

BRASSERIE AU BARON CUVÉE DES JONQUILLES

LOCATION: Gussignies, France

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

7% ABV

Brasserie au Baron is literally a stone’s throw from Belgium, so it’s not shocking that Cuvée des Jonquilles borrows heavily from the saison tradition across the border. Named for daffodils, the effervescent beer is fittingly a sunny blond and even a bit flowery in the nose. The flavor is marked by a crispness, a minerality, lemon, lavender, and some interesting phenolic notes.

LA CHOULETTE AMBRÉE & LA CHOULETTE BIÈRE DES SANS CULOTTES

LOCATION: Hordain, France

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed (Ambrée); Magnum, Brewer’s Gold, Golding (Sans Culottes)

8% ABV (Ambrée); 7% ABV, 22 EBU (Sans Culottes)

These two beers are contrasts in style and appeal. Ambrée, the brewery’s first beer, is made in the modern mode—dominated by malt, very smooth, and a little thick. It is robust enough to suggest a barley wine, though the brewer, Alain Dhaussy, is using caramel malts to evoke the “long boils at the beginning of the century.” Sans Culottes (literally “beer without pants,” a reference to the 1789 French peasant rebels who didn’t wear upper-class culottes) was brewed two years after Ambrée, in 1983, but it is a revival of the old farmhouse tradition. The beer is much thinner, effervescent, spicy, and tart—akin to what we would now call a saison. To American palates, the Sans Culottes will delight, while the Ambrée may seem heavy and ponderous. In France, Ambrée is the much more common and expected style.

THIRIEZ EXTRA

LOCATION: Esquelbecq, France

MALT: Pale, from French barley

HOPS: Brewer’s Gold, Bramling Cross

5.5% ABV, 1.050 SP. GR., 50 EBU

By some margin, this is the most vividly hopped of export French bières de garde. Extra (Étoile du Nord in France) is a limpid honey-colored beer with an impressive white head, but the nose is pure earthy hopping. Like La Choulette, Thiriez makes a standard French ambrée, so Extra comes as a sharp contrast—more like the spicy, dry saisons made across the border. Daniel Thiriez credits the English Bramling Cross hops (“a lot of them”) for the oily, peppery palate.

ST. SYLVESTRE 3 MONTS

LOCATION: Saint-Sylvestre-Cappel, France

MALT: Two- and six-row malts

HOPS: Nugget

8.5% ABV, 1.074 SP. GR., 20 EBU

St. Sylvestre’s offering has an elegance that begins with a hugely effervescent pop at cork opening and a Champagne-like cascade of gold and bubbles. The beer is just as stylish. A bit more estery than other bières de garde, its smooth malt flavors are kissed by a bit of peach (or is it apricot?), which further reminds one of pale wines.

THEILLIER LA BAVAISIENNE

LOCATION: Bavay, France

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

7% ABV

La Bavaisienne is a classic bière de garde, rich amber, ebulliently carbonated. It gets its color from wort caramelization, and leads with a brown sugar to toffee palate but, unexpectedly, not a sweet one. The finish is not exactly dry, but it is decisive, and helped along by a woody, herbal note that scrubs the palate for another sip.

SOUTHAMPTON BIERE DE MARS

LOCATION: Southampton, NY

MALT: Pale, wheat, Vienna, Munich, aromatic

HOPS: Magnum, Styrian Golding, Saaz

OTHER: Undisclosed spices

6.5% ABV, 22 IBU

If you’re looking for the taste of France stateside, Southampton has an excellent offering. Brewer Phil Markowski has crafted a beer with classic French character—burnished malts with a touch of nectarine, reminiscent of riesling. Markowski gooses it with some spicing, but it’s very subtle and just urges the flavors to pop.

AIX-NOULETTE, FRANCE

Brasserie St. Germain

NATIVE FRENCH BREWING

THE NORD-PAS-DE-CALAIS, THE REGION BORDERING BELGIUM, IS THE TRADITIONAL AS WELL AS MODERN CENTER OF FRENCH BREWING. IT’S ONE OF THOSE PLACES WHERE HISTORY IS A CONSTANT PRESENCE, AND NOT ONE FILLED WITH THE GLOSSY IMAGES FROM A TOURIST BROCHURE. THIS IS COAL-MINING COUNTRY, AND SCATTERED ALONG THE UNDULATING LANDSCAPE ARE WHAT LOOK LIKE CONICAL HILLS BUT ARE IN FACT IMMENSE SLAG HEAPS. FOR DECADES, COAL FUELED THE LOCAL INDUSTRY, AND THE NORD HAS AN UNGLAMOROUS, WORKING-CLASS PAST. IT WAS ALSO ON THE FRONT LINES IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR, A MEMORY THAT PERSISTS VISIBLY IN THE BATTLEFIELD MEMORIALS AND CEMETERIES THAT CROP UP EVERY FEW MILES.

This sense of history carries over to brewing, too. While much of the rest of France enjoys a freewheeling exploration of beer styles, in Nord-Pas-de-Calais they still cherish traditional brewing. When you enter Brasserie St. Germain, tucked into a recessed building on Route d’Arras in Aix-Noulette, you are immediately greeted by that history. In a beautiful, hop-draped room not currently licensed as a pub, the walls are lined, curiously, with signs for Bières Brasme. When co-owner Stéphane Bogaert tells the story of St. Germain, he doesn’t begin when he, his brother Vincent, and Hervé Descamps founded the brewery in 2003. He goes back much further, recounting the history of brewing in Nord-Pasde-Calais, the rise of modern bière de garde in the 1970s, and the importance of Brasme, which at one time brewed 215,000 barrels of beer in Aix-Noulette. Most breweries start their history with their own founding, but at St. Germain, they trace their lineage through that earlier brewery.

Old signs from Brasserie Brasme adorn the brewery walls

Indeed, all of that history is critical, because the men of St. Germain have thought deeply about what it means to run a French brewery. To the Bogaerts and Descamps, the future will be a return to local brewing, artisanal brewing, and a style of brewing that is peculiarly French:

Our philosophy is to respect the bière de garde tradition. The major activity of the brewery must stay with this kind of beer. That’s why I say to my colleagues that they should write ‘bière de garde’ on their labels; it’s profitable for everybody. We want to be different from Belgium and we want the people, especially in America, to talk about French beer. Bière de garde is something you can say, “Okay, it’s a French style.”

—STÉPHANE BOGAERT, BRASSERIE ST. GERMAIN

There are really two traditions in French brewing. The most recent are the bières de garde that developed a following in the 1970s—strong, malty, “garded” (lagered) beers. But there’s an older tradition that is more rustic and relies more on local agriculture. St. Germain decided to make bières de garde that were respectful of those made by the older breweries in the region. Their beer follows the general model laid down by Jenlain, Ch’ti, and others. They brew a blond, an amber, a printemps, and a hugely successful Noël. But they also wanted to make beers that were a part of the earlier tradition, when farmhouse breweries used more hops and local ingredients.

The Nord-Pas-de-Calais is one of the few places in the world where it’s possible to get all local ingredients, and St. Germain decided to make its beer entirely out of local crops. Hops are grown just down the road, and the barley, which now goes to Belgium to be malted, is also local (the nearby malt producer, Soufflet, provides them with specialty malts). The brewery even uses sugar from local beets to fortify its beers. Specialty beers include a piquant rhubarb-infused beer (Rhubarbe) that evokes old-time fountain sodas, and a roasty, copper-colored beer (Chicorée) made with chicory—an ingredient common in French beer a century and a half ago. Of course, the rhubarb and chicory are local products, too.

Hops became the centerpiece of the St. Germain line—not muscular American-strength hopping, but flavorful, aromatic hopping. That’s where the name Page 24 comes in. It is a reference to Hildegard of Bingen, one of the first documenters of the use of hops in beer (see page 20). Page 24 is the apocryphal location of these comments in her writing. Of course, working with only local ingredients has a couple of major disadvantages when it comes to hops. Local growers produce only a few types, limiting St. Germain’s recipes. Local farmers grow crops conventionally, too, so the brewery had to abandon organic beer. On the other hand, St. Germain is working with the farmers to cultivate a wider variety of hops; the English variety Challenger should be available soon. There are only eight growers left, and the patronage of St. Germain may well ensure they’re in business to supply local hops for years to come.

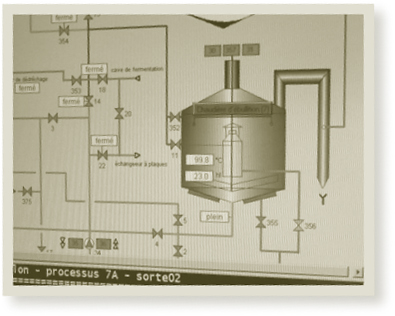

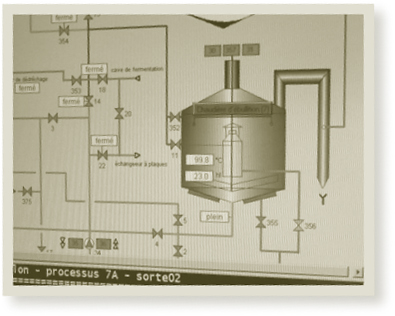

A futuristic-looking filter at Brasserie St. Germain

Even the computer model is French.

The central hurdle for French brewing is establishing an identity. Even in France, Belgian beers are far better known. “Everybody thinks Belgium when you say beer,” Bogaert acknowledges. “In this region, we are not so famous compared to Belgian breweries.” A generation ago, makers of bière de garde got the ball rolling and put France on the map. St. Germain hopes to continue its work and make bières de garde that are even more characterful and flavorful—and more French.