The saint in this mosaic is holding a mashing fork.

The ale brewed at the Abbey of Sint Sixtus near Westvleteren is easily the most coveted regular-production beer in the world. It’s not because of the beer—well, not entirely. To acquire a bottle, you must visit the abbey, which happens to be seventy miles from the nearest Belgian city. The last part of the journey sends you zigzagging through fields of Brussels sprouts on one-lane roads. The abbey itself is hard to miss, but no signs direct you to the restaurant where travelers are welcome.

When you do finally arrive at the one building on the planet where bottles of Westvleteren beer are sold, you have a final test: Will the gift shop be open? If everything goes according to plan (a plan that must include a meal with a creamy, mild slab of abbey-made cheese and a goblet of draft beer), you will leave the building with no more than one case of beer—the monks disallow hoarding.

Not all abbey ales are this hard to find, nor are all made in monasteries; yet they seem to possess the spirit of reverence, sanctity, and stillness that cloaks Sint Sixtus. In fact, there are only a handful of brewing monasteries, though secular, commercial makers do their best to invest their products with ecclesiastical essence. The beers in the abbey range are fit for chalices: deep, resonant, and alcoholic. There’s no one type—some are light, some are dark, some strong, some, well, not quite so strong—except that they should be special and rare, deserving of all the mystique. ■

MONASTIC BREWING may seem somewhat contradictory—devil’s water and godly monks—but it has a long history. Since its advent, brewing had been a solely domestic chore. Monasteries changed that when they took up brewing around the seventh or eighth century. The practice grew out of Cistercian rules that charged monks to be self-reliant and welcoming. Beer, safer than water, was a nutritious avenue to both ends. Monks grew their own barley (and, later, hops), made and drank their own beer, and offered a wholesome mug to pilgrims passing through.

Monks advanced the state of the brewing art by elevating it in scale and scope. Under Charlemagne, monasteries proliferated across Europe. At their height, 600 monasteries were making beer. In order to serve their growing consumer base, monks developed techniques of mass production that commercial breweries later adopted in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries: larger kettles and tuns, and better systems for managing the mash, boil, and fermentation. Monks were also the first to incorporate hops—or at least the first to write about their use—hundreds of years before they became a standard ingredient.

The saint in this mosaic is holding a mashing fork.

Commercial brewing eventually ended the monasteries’ preeminence, but they continued to make beer on a small scale. It took the French Revolution to end production completely at the close of the eighteenth century. The revolutionary government seized monastery holdings and scattered fleeing monks as far as Russia. However, with the fall of Napolean, and particularly with the birth of Belgium in 1830, monks had the opportunity to rebuild old monasteries or start new ones. Since Westmalle and Westvleteren began brewing in the nineteenth century, monastic brewing has slowly been adding new members to its small fraternity. There’s even a new kid on the block: Austria’s Engelszell installed a brewery in 2011. In its typical deliberative manner, the International Trappist Association (the body that oversees Trappist economic interests) took its time considering the monastery’s bid before adding it to the official list in 2012.

Meet the Trappists. Only one Catholic order currently brews beer (though that may change soon), the Trappists, a reform branch of the Cistercian order. Armand Jean de Rancé led the reforms in the 1660s, which called for stricter fidelity to St. Benedict’s rules; the order takes its name from the monastery at which he was abbot, La Trappe (the official name remains Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance).

Until 1962, however, the Trappists were not the only brewers using the word “Trappist” on their labels—commercial breweries regularly appropriated the name. Chimay and Orval pushed for legal protection and managed to get the law changed then, but commercial breweries continued to exploit loopholes.

In 1985, the Trappists won improvements to the law, and now only cheese, beer, and other goods made at a monastery can use the words “Authentic Trappist Product.” In this iteration, monks tightened the law so that to win the designation, beer has to be brewed inside monastery walls. Sounds clear enough, right? When you buy a beer with the hexagram seal and “Authentic Trappist” seal, you can be assured it was brewed at a monastery.

The trouble comes with a second designation. When the 1962 law was passed, breweries that had been making monastic-inspired beers had to scramble. Not all of these breweries were merely trading on the name—some had arrangements with local monasteries to sell beer under their name, with some proceeds directed back to the monks. Others used monastic names to evoke the history of their town or brewery. The nonmonastic breweries came up with the word “abbey” to describe their beers. All well and good until 1999, when the Union of Belgian Brewers gave sixteen breweries a special designation to indicate some vague monastic connection: “Recognized Belgian Abbey Beers.”

These relationships all vary, and they are in many cases no different from similar relationships in other countries. The language gives them a confused status and has led titans like Stella Artois/InBev (Leffe), Heineken (Affligem), and Alken-Maes (Grimbergen) to rub robed elbows with Orval and Westvleteren. Charity may encourage us to look at this as something other than a con job, but suffice it to say that the big producers are in no hurry to correct people who think their beers were monastery brewed just like “authentic Trappist products.”

The romance of the abbey was not lost on commercial breweries, which by the nineteenth century had begun to trade on the Trappist mystique to sell their own beer. Laws now protect the Trappist brand, but the romance has proved potent—Trappist and abbey ales have enjoyed a rapidly growing market in Belgium. Abbey-themed brands are among the most popular and have shouldered aside many older, more traditional brands. It is a strange irony that in a country where church attendance is at record lows, beer brewed at monasteries or associated with them are more popular than ever. ■

WHEN MONKS RETURNED to their ancient practice of brewing in the nineteenth century, they couldn’t turn to a distinct tradition. Monasteries had always been fixtures of local regions, brewing beer according to local, rather than Trappist, tastes. If you look closely at the extant Trappist breweries, you see traces of those older traditions. Like its region around Antwerp, Westmalle is famous for its strong blond ales. Westvleteren makes hearty, dark beers in the style of West Flanders. (Stan Hieronymus writes in Brew Like a Monk that Westvleteren’s beers used to be tart as well, situating them even more firmly in the regional tradition.) Finally, there is Orval, the oddball with wild yeast and fragrant dry-hopping, which seems to bear no resemblance to the other abbey ales. Yet it does taste a great deal like saisons, which were common in the south of Belgium where Orval is located. Trappist ales have grown stylistically closer together in recent decades, but they emerged from separate traditions—ones still faintly visible in their lineups.

That we can speak of them as a group at all is thanks to the constant pressure of a market that bends the arc of change toward customer expectation. Commercial breweries entered the market with their own versions of preexisting beers, replicating features of the originals. Styles like dubbels and tripels were made double and triple strength, further solidifying these beers as hallmarks. As a result, abbey ales now constitute a range of ales that bear consistent similarities. They are strong beers fermented warm to produce an interesting yeast character, but are dry and crisp. Some are dark, some are light, but they are all brewed with sugar to produce a lean body, help add strength, and dry the beers out. They are rich, effervescent, and luxurious.

Yet “abbey ales” are not a well-kempt style. There are stragglers like Bosteels Tripel Karmeliet, made with oats, wheat, and spices. Orval is a style unto itself, the one abbey ale made with wild yeast. Monasteries occasionally offer lighter beers like Westvleteren’s fresh, hoppy Blond, Chimay Dorée, and Westmalle Extra. Some of the commercial abbey-style ales like Leffe, Affligem, and Grimbergen are closer to pale ales.

There are two curiosities about the beers we now know as dubbels and tripels. The first is that they are associated with monastic brewing. Historically, breweries regularly made double-strength beer (dobbel gerst, double Diest, and double uytzet, to name three, were standard styles in the nineteenth century). I know of no reference to triple-strength beer prior to the twentieth century, but the idea of a range of beers, each stronger than the original, can be charted back to the distant past. Yet now dubbels and tripels are recognized solely as monastic-style beers.

The second curiosity is that the dubbel is now exclusively a darker beer while a tripel is golden. There’s no reason a brewery couldn’t make a dark tripel or a golden dubbel—except that convention now dictates the reverse. Such is the caprice of style evolution.

With its gracious space, polished copper equipment, and stained glass windows, it’s not uncommon to hear Rochefort’s brewhouse described as the world’s most beautiful.

Whatever their original source (accounts vary), no one disputes that Westmalle popularized golden tripels—nor that every other tripel will ultimately be compared to Westmalle’s. The hallmarks of that beer are strength (9.5% ABV)), dryness, and assertive hopping. The abbey is near Antwerp, a region where strong hoppy beers gained early popularity. As the style has evolved and spread, it has retained its strength but not always its hoppiness. St. Feuillien, Gouden Carolus, and St. Bernardus are all excellent, but sweeter, examples.

Tripels are now among Belgium’s bestselling styles, but it wasn’t always so. As recently as 1980, Westmalle’s style-defining Tripel constituted less than 30 percent of production. Dubbel, accounting for the rest, was the flagship. Three decades later, again owing to the vagaries of the market, the products had nearly reversed position.

As a consequence, dubbels are now less common, though they have a longer lineage. These brown beers were once the norm in Belgium, and a rich color was the sign of quality. Even now, all the Trappists, with the exception of Orval, produce brown beers, and many emphasize them. Brewed to almost the strength of tripels, they are a homier style, with a comforting toasty or cocoa character wrapped in a warming blanket of malt. Rochefort 8 might be the exemplar of style, but St. Bernardus 8 is the most characterful and interesting, with a rich cocoa base, a touch of roastiness, and a dry biscotti finish.

As if 8 to 9% ABV tripels weren’t strong enough, the Trappists have located a higher rung on the ladder. Most of these very strong ales are dark—Westvleteren 12, St. Bernardus Abt 12, Achel Extra, and Rochefort 10. Very strong beers aren’t new, but the name “quadrupel” is; La Trappe coined the term to describe a beer that has some of the darkness of those other dark abbey ales, but enough amber-orange luminosity to connect it to popular tripels. Fortunately, no brewery has yet tried to pioneer a quintupel. Yet.

In terms of enjoyment, few beers age as well as dark, strong abbey ales. Artisanal Belgian breweries typically re-ferment their beer in the bottle (as all the monastic breweries do), further preparing them to age well. Stored at a cool temperature, these beers will mature for years, continuing to evolve like Port wine.

You might not think Catholic monks would brew exceptional beer and yet of the products produced by the Trappist monasteries of Belgium and the Netherlands, three are regarded as world standards, one is arguably the best beer in the world, and none is less than excellent. When you stop to consider their business model, though, it makes sense that the monks would brew very well. They have the long view, not regarding beer as a commodity so much as another extension of God’s work. They are in no rush to turn a buck and have no intention of becoming multinational giants. The monks bring care and attention to their beers, and they have been perfecting them for decades. Considering these facts, it isn’t surprising in the slightest that they would produce uniformly wonderful beer.

The Belgian Degree System. Monastic institutions are dedicated to preservation, and it’s little wonder that their beers could serve as exhibits in the museum of brewing history. Achel and Rochefort, for example, still use the old Belgian degree system of measuring gravity. It’s a simple system where specific gravity is converted to degrees by subtracting one from the number and multiplying by 100. The system is visually intuitive: a beer of 1.060 becomes 6°, 1.080 becomes 8°, and so on. Rochefort’s line of beers include 6, 8, and 10, and they correspond to gravities of 1.063, 1.078, and 1.096 respectively.

For people familiar with the Plato system (see page 50), Belgian degrees can be confusing. In the Plato system, a degree works out to about 0.004 on the specific gravity scale; a beer of 8° Plato is therefore a puny 1.032. Conversely, a beer of 8° on the old Belgian system works out to about 1.079, or 19° Plato.

Following is a description of each Trappist brewery, beginning with the oldest.

WESTMALLE

(Abdij der Trappisten van Westmalle)

The monastery was founded in 1794, just northeast of Antwerp. The monks started brewing in the 1830s for their own use, and started selling beer to locals in the 1870s. In 1921, Westmalle decided to sell its beer more widely. The famous lineup evolved until settling to the current three in the 1950s. Since that time, Westmalle hasn’t fiddled with them, though the recipes do change to adjust for malt variations.

Brewery or house of worship? The Trappists view beer-making as an extension of the Lord’s work.

Everyone knows that tripels are golden-colored, but until recent decades, strong ales were largely brown. How did tripels lose their color? Westmalle is one possible candidate. Certainly no brewer is more associated with the long tradition of golden tripels than Westmalle, which popularized the strong golden style even if it didn’t invent it. The abbey’s Dubbel is slightly less famous, but its impact just as strong. It remains a ruddy brown—one of Belgium’s classic hues.

The beers form a nice counterpoint to one another. Both express a fair amount of spicy, estery yeast character, but the beers take these qualities in different directions. The gorgeous Tripel is known for its amazing head stability. A beer of 9.5% alcohol should burn off its foam, but if you look in your goblet following your final swallow, you may well find a final skiff, coating the bottom of the glass like a dusting of snow. Tripel is hoppy at 39 IBU, something that is not evident in the aroma (those hops help the foam stick around). Instead, the sweet, rich, alcoholic notes subtly hint at their presence on the first impression. The spicy hops come later and rescue the beer from becoming overly rich. The body is full and creamy, effervescent, but not heavy. In Tripel, yeast accentuates spice. Dubbel is more gentle and homey. The aromas and flavors are toffee sweet, leavened with figs and banana. The malts are dry, though, scone-like, and the finish is crisp. Here, the yeast has more fruit and the spice becomes a balancing note.

WESTVLETEREN

(Sint-Sixtus Abdij van Westvleteren)

The Sint Sixtus monastery was founded in 1831 when monks from Sainte Marie du Mont des Cats abbey (which would, fifty years later, send monks to found La Trappe) joined a hermit living in the woods. These woods just happened to be outside Poperinge in Belgium’s hop-growing region. The small community grew slowly, and monks added the brewery seven years later. In a rare exception to the historical rule, the brewery went undisturbed in World War I, and in 1928 it started selling to the public to fund an expansion. In World War II, however, the monastery wasn’t so fortunate and had to suspend brewing. In 1946, Westvleteren licensed nearby St. Bernardus to brew its products under the Sint Sixtus name, an arrangement that lasted until 1992. (St. Bernardus continued to brew the erstwhile Westvleteren line under its own name; see box on page 305.)

Westvleteren’s beers are undoubtedly the most coveted in the world—at least for regular, year-round beers. The reason is because the monks refuse to ramp up production. Beer is sold only in the monastery café, In de Vrede, and by the crate (one only, please!) at the brewery dock. The monks believe the brewery serves the monastery, not vice versa, and the restricted production is a matter of practice for the monks who spend six hours of their day in prayer.

Until 1999, the brewery made a range of beers from a 4% ABV light table beer to the signature 10% strong dark ale that is now known as 12. That year, the brewery replaced the two weakest beers with a hoppy blond ale—a nod to both changing convention as well as local hop fields. The most famous is the aforementioned 12, a beer that regularly fetches twenty dollars or more on after-market sales. It is a warming, bready beer with banana and hazelnut notes. It ages well for years and acquires the character of an English barley wine. The 8 is roastier, with touches of smoke and caramelized sugar. The real treat is the least famous of the beers, the Blond. Far more complex than the others, it has the hazy, rustic quality of a saison. The nose and palate have the floral scent of blossom and the sweetness of honey, yet it is a crisp, dry beer with rich hop character. An irony, but true—hidden among the most famous beers is an overlooked wonder that is the true classic.

Scourmont Abbey, where the illustrious Chimay brewery is located

CHIMAY

(Notre-Dame de Scourmont Abbey)

Chimay is the best known of the Trappist breweries, and most beer fans will have had a glass—it’s available at many grocery stores and you even see it on tap sometimes (it’s the only Trappist beer sold that way). One shouldn’t construe this availability as evidence that it’s a mass-market beer, though; Chimay is one of the most highly regarded brands in the world.

St. Bernardus. When wandering wild forest land, you will from time to time come across two trees growing so closely together that they share a single bole near the ground and only start to be two trees when you look upward; such is the case with St. Bernardus and Westvleteren. Following World War II, when the monks at Westvleteren decided to locate their brewing activities outside the monastery, they looked to a cheese maker in the village of Watou. The little operation was already called St. Bernardus, a vestige of its origins as a monastic community that had fled there from France.

The monks from Westvleteren relocated the brewing equipment to Watou and the brewmaster taught St. Bernardus how to make the beer according to their specifications and methods. The first three beers brewed there will be familiar to modern fans of the brewery: Abt 12, Prior 8, and Pater 6, all dark ales in the tradition of Flanders. At St. Bernardus, they used the same yeast and ingredients to make these beers as they had at Westvleteren, and have now been making them for nearly seven decades. In an interesting twist, one could argue that these three beers carry the Westvleteren legacy the closest. They (and all the brewery’s beers; the line expanded to eight offerings) use Westvleteren’s original yeast strain, which the monks no longer use. In addition to the original three beers, St. Bernardus brews a well-regarded tripel, witbier, and Christmas ale.

Monks built the Notre-Dame de Scourmont Abbey near the village of Chimay in 1850 and equipped it with a brewery. Like most of the Trappist monasteries, the monks cast about with different recipes and multiple iterations before finding their voice. The current beers sprang from a collaboration between Father Théodore and the famous scientist Jean de Clerck. Between the late 1940s and 1966, the monastery introduced the familiar chromatic series—Red, White, and Blue. Still, the recipes change slightly. In addition to changes in fermentation, the hops also shift. Chimay surprisingly prefers American hops, using Galena, Nugget, and Cluster at various times to bitter, changing varieties for optimum flavor. (Hallertau is used to flavor.) Interestingly, it doesn’t use whole hops, but extract, a quirk since picked up by Orval and Westvleteren but rare elsewhere.

Although most people know them by their colors, the beers actually have names. Première (Red) is the lightest in the range at 7.1%, and is roughly dubbel-like in style. Cinq Cents (White) is a tripel weighing in at 8.2%, and Grande Réserve (Blue), at 9%, can be slotted with stronger dark abbeys like Westvleteren’s. The line shares a strong family resemblance: The beers are elegant, sporting heady, refined aromas and rich tones, but they’re delicate, light, and quite dry. Of the three, Grande Réserve is the standout. It has a spicy, complex nose and a deep chestnut body topped by a silky latte head. The flavor is dessert-rich: creamy and soft with vanilla notes and plum, and then the long finish, a little sharp with alcohol, just to remind you that this is an adult’s beverage.

LA TRAPPE (Abdij Koningshoeven)

In 1880, the abbot of Sainte Marie du Mont des Cats, concerned about the French government’s attitude toward religious institutions, sent Brother Wyart to the Netherlands to look for a potential site in friendlier lands. The envoy found a lovely farming area near Tilburg that the locals called Koningshoeven—the Royal Farms—and the brothers decided to establish a second monastery there. They renovated a sheep barn and, to help support a growing population, built a brewery four years later.

There are several ways in which La Trappe is unlike the other Trappist breweries, and it has little to do with location. Notably, the monastery started brewing lagers and continued to do so for a hundred years. In 1969, Koningshoeven (a name used not only for the land but also the monastery itself) licensed its brewery to Stella Artois, an arrangement that lasted over a decade. When the monks resumed control of the brewery in 1980, they made the momentous decision to abandon lagers and produce beers typical of the Trappist family. The licensing experiment didn’t sour the abbey on commercial partners, though, and in 1999, Koningshoeven set up a partnership with Bavaria Brewery (a Dutch company, despite the name). Now Bavaria rents the equipment and buildings from the abbey and operates the brewery for the monks. The partnership caused a dispute over La Trappe’s status as a Trappist brewery, but in 2005 the International Trappist Association affirmed the affiliation—the beer is officially Trappist.

Despite the abbey’s historical roots, the beers of La Trappe are now in the familiar range of strong ales—a Dubbel, a Tripel, and the first beer ever called a Quadrupel. Of all the Trappists, La Trappe’s beers are the sweetest and least complex. Hop character is absent or nearly so, and the yeast character enhances the sense of sweetness. The beers find their balance through alcohol heat—in the Quadrupel, it’s legendary—yet the relatively low levels of attenuation leave the beers on the sweet side.

ROCHEFORT

(Abbaye Notre-Dame de Saint Rémy)

The Abbaye Notre-Dame de Saint Rémy began life in 1230 as a convent; it didn’t become a monastery until 1464. Brewing started in 1595, and monks cultivated hops and barley on the grounds. After plagues, schisms, and wars ravaged the property in the coming centuries (it was sacked by Calvinists in 1568), the entire monastery began restoration in 1887. They completed the brewery in 1899—sans hop and barley fields.

Rochefort’s early beers weren’t very good. By 1950, it was in danger of being put out of business by Chimay, sixty miles away. Instead, Chimay sent Jean de Clerck to help it make better beer. Over the next five years, Rochefort introduced the beers it still produces, though two of the names have changed.

The beers of Rochefort are simply made. They use two principal base malts as well as sugar and wheat starch to boost alcohol. The water is much prized for its purity and hardness, and the brewers believe it’s the key to Rochefort’s complexity. They use two hop varieties, Hallertau and Styrian Golding, and finish with a blend of two yeast strains. And just to mix things up, they tuck in a tiny dash of coriander.

The brewery produces just three beers: 6, 8, and 10. They are all brown ales and have a similar raisiny, earthy, bready nose. The flavors tend toward sweetness, and as the beer rests on the tongue, is something like a liquid fruitcake: lots of winter fruits, a healthy warmth from rummy alcohol, and you can even find bread and nuts if you let your tongue soak long enough. A vigorous effervescence and those hard water notes balance the beers and keep them from cloying.

ORVAL (Abbaye Notre-Dame d’Orval)

A full description of the brewery and beer.

ACHEL (Sint Benedictus Abdij)

When most people think of Trappist breweries, they count six Belgian and one Dutch. But it’s really one and a half Dutch. The Abbey of St. Benedict started life in 1686 as a hermitage (that’s what its informal name, Achelse Kluis, means) in Achel, Belgium, near Valkenswaard, Netherlands, with part of the property located across the border in the Netherlands. The monks were expelled from the monastery in 1789, but a priory was reestablished by monks from Westmalle in 1844, complete with a brewery and maltery. In a familiar story, the Germans destroyed the brewery during World War I and despite plans to rebuild it, Achel went brewery-less until the late 1990s.

When the abbey decided to reinstall a brewery, the monks relied heavily on the Westmalle influence. Brother Thomas, a retired monk from Westmalle, created the initial formulations and conducted the first test batches. The recipes for Achel’s line came into focus over the course of the first few years (with later help from Brother Antoine, a monk from Rochefort) and have remained constant since the mid-2000s. The link between the abbeys continues through use of the same yeast strain.

Achel’s three main beers are a blond and a brown called 8° (both are 8%) and a strong dark beer of 9.5%. At the brewery, they also offer a 5° beer, but only sell it onsite. Like most of the Trappist ales, the recipes for Achel’s are elegantly simple: pilsner malt, sugars (light or dark, depending on the beer), a bit of darker malt where necessary, and Saaz hops. Extra, the dark beer and Achel’s strongest, is the most complex. It’s actually a dark amber more than fully brown, and the foam is no match for all that alcohol. Rum notes come through the nose and palate, with burnt sugar, prunes, sarsaparilla, and a dash of banana ester. The alcohol, though deadly to the beer’s head, is gentle and soothing in the drink. Perhaps because Achel has not had decades to refine its palate into something unique and unmistakable, the brewery’s beers, while lovely, seem to echo some of their inspirations at Westmalle and Rochefort.

STIFT ENGELSZELL

The Abbey of Stift Engelszell is located in far northern Austria on the Danube River, just one mile south of the German border, and fewer than twenty southeast of the Czech Republic. Founded in 1293, it spent 500 years as a Cistercian monastery until it was dissolved and placed in secular hands in 1786. Trappists took it over again in 1925, lost it during World War II (when Hitler dispatched five of the brothers to a concentration camp), and started anew after the war.

The monastery is more famous for liqueurs and cheese, but it also added the world’s newest small Trappist brewery in 2012. The International Trappist Association accepted its application a year later and it now offers two products: a strong saison, Benno (which the brewery calls a tripel), and a strong dark ale named Gregorius. Of the two, the Benno is the more interesting beer, with spicy farmhouse notes and a dollop of honey that adds to a cakey, sweet palate. Early bottles were not quite in focus, but the beer is unique and like nothing in the Trappist range—given years to evolve, it might become a standout in its own right. ■

WHAT DISTINGUISHES ABBEY ales is not their methods—which are typical for Belgium—but their execution. The breweries making the hallmark beers have been doing so for a very long time: Chimay’s most recent recipes date to the 1960s, Orval’s to the 1930s, Rochefort’s and Westmalle’s to the 1950s. St. Bernardus and Westvleteren, breweries with entwined histories, have recent recipes originating just after the Second World War. Any alterations in method, equipment, and ingredients were made only after careful consideration and have been implemented incrementally. The beers are so good because they’ve been fine-tuned for decades.

The beers begin with a base of European pilsner malt and a sizable portion of sugar—this is key to their profile. Even the heftiest abbey ales are light bodied, and that comes from grists of up to 20 percent sugar. Invariably referred to as “candi sugar,” Belgian grists actually employ various types of sugars and sometimes a mixture within one grist. The basic sugar is sucrose (the same table sugar used in baking), usually in liquid form, and often it comes from locally grown beets. In dark beers, breweries use a caramelized amber syrup that adds both color and a fruity, rummy flavor. Dextrose is a slightly different form, also common.

Hops, often a neglected element in Belgian brewing, are sometimes used to great effect in monastic beers. Because the beers are so strong, even where they’re not marked by hop character they must be balanced. Spiciness plays an important role in many abbey ales, and hops work with yeast to create the flavor. By American standards, Westmalle and Orval aren’t aggressively bitter, but they are green and lively, hoppier than most Belgian ales. This inclination has opened the door to other hoppy interpretations such as those by De Ranke (Guldenberg). A minority of breweries add spice, usually as a subtle accent note.

As with so many Belgian styles, yeast takes center stage. Belgian strains are famous for producing more esters and phenols than ale strains in the United States and Britain. That’s true of the Trappist yeasts, too, though the effect is not uniform. Wyeast Labs ran experiments on the strains they isolated from the breweries and found that some (Chimay and Westmalle) were predisposed to produce clove notes. The yeast from Rochefort produces a particular ester that tastes like roses or honey. The yeasts are all alcohol tolerant and don’t produce some of the harsh fusel alcohols other strains do in similar circumstances.

One of the biggest factors in the way these yeasts behave is temperature. The higher the temperature, the more esters and phenols a yeast will produce. Belgian brewers pitch at different temperatures and let the activity of the yeast raise the temperature to different levels. Rochefort pitches at 68°F and lets the temperature rise just to 73°F. Chimay is pitched at the same temperature but is allowed to rise to 82°F. Orval is pitched at a cool 58°F and allowed to rise to 72°F; however, in Orval’s case the brewers have found that time is more important than temperature within that range. Orval always takes five days to ferment, and the brewers adjust the temperature to speed it up or slow it down. All of these decisions affect the way the final beer tastes, giving them their unique character.

We have a lovely real-time experiment of how the same yeast strain behaves differently in different circumstances. Westmalle provides fresh cultures of its strain to Achel and Westvleteren (that is, there’s no “house effect” of later-generation mutations) and all make a similar dubbel ale. Westmalle begins fermentation at 64°F and lets it rise to just 68°F; Achel also starts at 64°F but allows it to rise to 73°F; Westvleteren goes warm, from 68°F all the way to 84°F. The effect is pronounced. Westmalle’s dubbel is smooth and dry, characterized more by the malts and sugars than yeast. Achel 8° picks up a bit more fruit from the esters. Westvleteren 8, by contrast, has an assertively phenolic smoky note. None could be confused for the other.

Abbey-style ales have become popular enough that they are now brewed around the world. In deference to their august origin, most breweries tend to follow the spirit of the Trappist ales, though American breweries are less likely to use sugar (or use less when they do), more likely to use color malts, and tend to ferment cooler. There are now hundreds of examples of these beers, and many made by secular breweries are exceptional. ■

ABBEY ALES HAVE gone mainstream. If we consider the Trappists the starting point, then there has been a bit of creep away from their boozy standards. Three of Belgium’s bestselling brands are sold with an ecclesiastical gloss (Affligem, Grimbergen, and Leffe), but they’re all in the 6% ABV range—a mass-market concession well below the strengths of the Trappists.

In the United States, abbey ales have gone the other direction, toward strength. They often skip the dubbel and go straight for robust tripels. Americans have also championed the quadrupel, inevitably called “quad.” American consumers are understandably confused by why a dubbel would be brown, a tripel blond, and a quadrupel brown again, and perhaps for this reason, there seems to be a trend toward golden quads as well. Avery’s The Reverend, Victory’s V-12, and Schlafly Quadrupel are all on the copper-orange continuum.

There may be a relationship between tripels and a very American-style beer: the double IPA. When American breweries were looking to make lean, golden-base beers to act as hop tinctures, they discovered techniques the Trappists have long used. Both styles are made with pale malts, use sugar for lightness and attenuation, and are brewed to great strength. In a hoppy tripel like Westmalle you can even see a direct link. It’s odd to think of such an American style as the off-spring of such a Belgian one, but the links are more than cosmetic. ■

THE ROMANCE and mystique of the abbey and Trappist ales make them the standard-bearers for this category of beer, and this is why they were all treated and described separately in this chapter. Their products do, however, have secular equals. It’s hard to corral them all into a cohesive group—there’s no abbey “style,” after all—but many make their identities known through allusions to the ecclesiastical. Here is a selection of good commercial imitations to try.

LOCATION: Watou, Belgium

MALT: Alexis, Prisma, roasted

HOPS: Target, Styrian Golding

6.7% ABV

Often overlooked is Pater 6, one of the finest abbey ales made. Amazingly creamy and fluffy, it has a deep, nutty palate with a touch of roast and dark fruit, and a surprisingly dry finish. In Belgium, 6.7% ABV may be considered a “moreish” strength—if so, this is its avatar.

LOCATION: Fort Collins, CO

MALT: Pale, chocolate, Carapils, caramel, Munich

HOPS: Willamette, Target, Liberty

7% ABV, 1.066 SP. GR., 20 IBU

New Belgium’s offering has the tell-tales of “high fermentation,” namely banana, bubble gum, and clove, those esters and phenols that come from warm fermentation. The heart of the beer is cocoa, with a caramel and bread edging. It’s sweet, warming, and inviting.

LOCATION: Krebs, OK

MALT: Belgian pilsner, Special B, aromatic

HOPS: Perle

8% ABV, 20 IBU

Choc’s dubbel is on the far side of sweetness, and the brewery helps keep it from cloying with volcanic effervescence. The flavors will remind you of dark foods—brown sugar, raisins, and chocolate. The sugars begin to gather with warmth, giving it a wassail-like quality.

LOCATION: Chambly, Québec, Canada

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

OTHER: Coriander

9% ABV, 19 IBU

Unibroue was way ahead of its time, providing North America with Belgian-style ales that were accomplished enough to rival the originals. La Fin du Monde was an early triumph: a huge, buoyant ale that froths into a tulip glass with energy and life. A sweet beer further sweetened by coriander, it has complex esters and phenols that open up in the mouth. The swallow brings a surprisingly crisp finish.

Grimbergen is brewed by Alken-Maes, not monks, but the large beer company is happy to capitalize on the confusion.

LOCATION: Rulles, Belgium

MALT: Pilsner, pale

HOPS: Amarillo, Cascade, Warrior

OTHER: Dark sugar

8.4% ABV, 1.074 SP. GR., 38 EBU

La Rulles is a fascinating example of modern Belgian brewing. Gregory Verhelst founded the brewery in 2000 and borrowed Orval’s yeast. But in putting together his tripel, Verhelst looked to Yakima, Washington, for hops that would give it a tropical flair. It is a rustic beer, though, with peppery yeast character, a grain-y, honeyed malt base, and wild-flower aromatics.

LOCATION: Le Rœulx, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

OTHER: Undisclosed spices; dextrose and maltose syrup

8.5% ABV

When St. Feuillien reclaimed its brewing tradition from Du Bocq Brewery, to whom it had entrusted it for a decade, it launched Tripel, now its flagship. A distinctive take on the style that depends on hard, mineral-rich water and a very dry palate. Malt aromatics blend with unidentifiable spices (which the brewery, protective of its formulation, keeps a secret) that are at turns herbal, grassy, and tingly with eucalyptus. The yeast contributes more spiciness, which accentuates the dry palate and minerality.

LOCATION: Watou, Belgium

MALT: Pilsner, black

HOPS: Target, Saaz

OTHER: Sucrose, dark caramel syrup

10.5% ABV, 1.090 SP. GR., 22 IBU

Despite its nearly ebony color, Abt 12’s only roasty notes come across as dry cocoa; the rest of the nose and palate are dominated by fruit. Lots of plum and raisin marry a refined, vinous palate. Like the Pater 6, it is a creamy beer, but—thanks to a large dose of sugar in the grist (just below 20 percent)—it’s thinner and more sharply alcoholic, like brandy. Dessert in a glass.

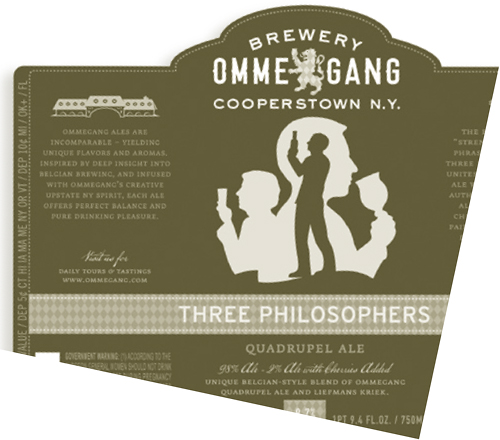

LOCATION: Cooperstown, NY

MALT: Pilsner, pale, caramel, extra special, Munich, Belgian aromatic

HOPS: Styrian Golding, Hallertauer, Spalter Select

OTHER: Dextrose, Liefmans Kriek

9.2% ABV, 1.090 SP. GR., 21 IBU

Three Philosophers came from Ommegang’s collaboration with homebrewer Noel Blake and is a slight departure from classic Belgian examples. The base beer is brown-sugar sweet with a raisiny, chocolatey quality. This is then blended with 2 percent Liefmans Kriek (Ommegang and Liefmans are part of the Moortgat family) for a cherry finish. It’s a decadent treat.

IF A COUNTRY THE SIZE OF MARYLAND CAN BE SAID TO HAVE REMOTE AREAS, THE MONKS OF THE ABBAYE NOTRE-DAME D’ORVAL FOUND ONE. THE GENTLE UNDULATIONS OF CENTRAL BELGIUM TURN TURBULENT IN THE ARDENNES OF THE SOUTH, WHERE OPEN FIELDS GIVE WAY TO FOREST LAND AND RIVER VALLEYS LACED IN MIST. THE MOUNTAINS AREN’T HUGE, BUT THEY OFFER DRAMATIC VIEWS AND, FOR PEOPLE SEEKING SOLACE, QUIET POCKETS PROTECTED BY TREES AND PEAKS. FOR NEARLY A THOUSAND YEARS, PEOPLE HAVE USED THE LAND AROUND ORVAL ABBEY FOR JUST THIS PURPOSE.

The first monks arrived from Italy in 1070, but abandoned the site shortly after. Monks returned and completed the abbey in 1124. In the following centuries, the monastery bore the suffering that scarred Europe: Orval was destroyed by fire and war (and dutifully rebuilt) in the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries. At the end of the seventeenth century, the abbot Charles de Bentzeradt established Orval as a member of the Order of the Strict Observance (the Trappists). But the monastery’s grace period didn’t last. Once again, the monastery was razed in 1793 during the French Revolution. Although the current monastery looks hundreds of years old (and there are ruins that stand as testament to its history), Orval was rebuilt for the last time beginning in the 1920s—once more of the ochre-colored sandstone known locally as pierre de France.

The brewery was completed in 1931, well before the monastery—and indeed, the brewery was conceived in order to fund construction. Every abbey has its own method of managing its brewery. Sometimes monks are still involved (Westvleteren), while in other cases the brewing has mostly shifted to lay brewers. At Orval, monks never brewed. Instead, they set up the brewery as a private business that operates under their direction inside the monastery. Currently, 45 percent of the proceeds are adequate to maintain Orval; the monks use the remaining 55 percent for their charitable activities. As François de Harenne, administrative and commercial director of the brewery, put it: “It is their company within their walls, but it is not really their activity.”

Unlike the other Trappist breweries, Orval has only ever produced a single beer. It is a curious blend of influences. The first brewer was a German named Martin Pappenheimer, who was in turn assisted by John Vanhuele, a Belgian who had spent much time brewing in England. In Orval’s telling, the vibrant hopping came from Pappenheimer and Vanhuele was the source of infusion mashing and dry-hopping.

The lovely Abbaye Notre-Dame d’Orval

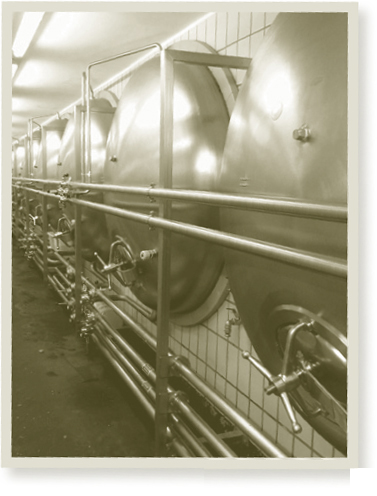

Although the mash/lauter tuns and kettles are made to look like old coppers, the glass floor reveals just how modern the brewery is.

The beer is little changed from the original recipe, crafted during a time when British beer was popular in Belgium. Orval uses two types of caramel malts, typical of English ales, but rarer in Belgian ones. The brewery uses hard water and mashes at a low temperature, then adds a stiff dose of hops (Hallertauer, American hops, and Strisselspalt, which have come to replace Styrian Golding) during the boil. At this point, it bears a strong resemblance to English pale ales, and that effect is enhanced by dry-hopping. But then Orval shifts gears. After a five-day fermentation, the beer goes to horizontal tanks where it is dosed with a second yeast infusion that includes Brettanomyces.

Horizontal fermenters, where Orval is dosed with wild yeast and dry-hopped. The fermenters extend back 15 to 20 feet.

One of the specially prepared sachets of hops for use in the horizontal fermenters. Ten bags will go in each fermenter.

There’s no reason to doubt the story of Pappenheimer and Vanhuele, but what about the wild yeast? If anyone knows who inspired that, they’re not talking. The yeasts begin to dry out the beer and work with the carbonate water—straight from the “Matilde spring” (see “The Legend”)—to stiffen it. It spends three weeks in the horizontal tanks and another month in the bottle, ripening. At release, it is a beer of just over 6% alcohol—hoppy, dry, and rustic. And here’s the most curious thing of all: Despite the influence of two foreign brewing traditions and the creep of decades, Orval would be very familiar to nineteenth-century saison producers of the region. It is justifiably called one of the country’s most traditional beers and is firmly in the saison family.

Orval went through a major renovation in 2007 that nearly doubled the brewery’s capacity to 67,000 hectoliters (about 57,000 U.S. barrels). The abbey upgraded the brewhouse for greater efficiency; a week’s brewing on the old system can now be done in a day. To ferment the increased capacity, Orval had to switch from open primary fermenters to more space-efficient cylindro-conical fermenters. The brewers were worried that it would compromise the flavor profile, so they spent three years in transition. De Harenne described the process: “We had part of the beer fermented in open vessels and part of it in cylindro-conical tanks. And when we were completely sure there was no difference in the taste of the beer coming from one side and the other side, we mounted the other five cylindro-conical tanks.”

Unusual for a Belgian brewery, almost all the production stays in Belgium. Just 14 percent is parceled out to the rest of the world, and demand far outstrips supply. There’s no more room to grow on the monastery premises, and the monks want to keep production entirely within the walls at Orval. The world is getting as much Orval as it ever will.

It is true that Orval makes only one product (a second product sold only at the monastery, Petit Orval, is just a diluted version of the original), but it’s a shape shifter, becoming very different beers as it ages. One is vibrant and spirited, marked by hops that are as resinous and green as any in Belgian beer. As Orval ages, the hops fall back and the Brettanomyces comes on, providing a lemon-zest note. The beer gets drier the longer it ages, and will become an austere, sherry-like ale of enormous complexity. Although there’s a loss of liveliness, Orval becomes more soulful, like an older singer whose range has been replaced by life and character. Wild yeasts constantly change the beer, making mutability its nature.

It is bottled at a strength of 6.2%, but can pick up another full point of alcohol as the Brettanomyces continue to work. It is one of the few beers regularly cited as the best by other Belgian brewers, all of whom have preferences about at what age Orval achieves perfection. Put a few bottles in your cellar and get them aging so you can determine your preference as well.

On Orval’s label you will find a picture of a fish with what turns out to be, on closer inspection, a golden ring in its mouth. There’s a legend behind the image, and it starts with the Tuscan Countess Matilde, a widow and one of the first arrivals to the region in the eleventh century. Before the monastery was built, she was sitting near a spring to rest and restore herself. When she reached into the spring, her wedding band slipped off. Distraught, she immediately started praying and before long a trout rose to the surface of the water, her golden ring in its mouth. “Truly this place is a Val d’Or [valley of gold],” she exclaimed. To this day, the pool of legend enjoys a prominent place at the monastery—and the spring remains the source for the beer.

Fields just outside the abbey, a reminder of the self-sufficiency of the Trappist monks