Wild and aged in bourbon barrels, Cascade’s deep black Bourbonic Plague proves that wild ales defy typecasting.

Imagine you’re the brewer at a modern facility, standing in front of a gleaming steel conditioning tank. Do you marvel at the technological advancement that has allowed you to make the purest beer in the long history of brewing? Do you silently praise the caustic chemicals that return your equipment to laboratory cleanliness? Do you sing hosannas because, unlike your predecessors from centuries past, you no longer have to contend with souring microorganisms that will quickly spoil your beer? You do not.

Instead, you wonder what it would be like to brew beer as they did during the Thirty Years War, using techniques that would surely produce tart and funky beer unpalatable to the great majority of twenty-first-century beer drinkers. Sure, the process is slow and expensive—but it’s unpredictable, too! Bizarrely enough, this roughly describes the thinking that led to a growing number of strange and wonderful beers made in the United States and Italy. ■

THE MODEST Dan Carey does not claim to have single-handedly reintroduced tart ales to the modern world—but he probably could. It was actually the reason he and his wife, Deb, founded New Glarus Brewing in Wisconsin in 1993, though his love of acidic beers goes back to the previous decade and a continent across the sea. “When I was an apprentice in Germany, my wife and two daughters and I were living there and we rented a car and drove across the border into Belgium on vacation. That was 1986.” By chance, he stopped in at the Lindemans brewery where he encountered the magic of lambic brewing. It was then “a rustic farmhouse brewery and [René Lindemans] was very open and he showed us how he brewed the beer. We thought it was just cool.”

Dan tried to figure out how Lindemans did it, but it took him years. Working in Oregon at brewery fabricator JV Northwest, he tested out different practices on a 15-gallon system he cobbled together from the company’s scrap pile. When describing the period, he pauses for two or three beats before allowing, “It was difficult. It was difficult to figure out how to brew it, that’s for sure.” But figure it out he did, and afterward he turned to his wife and said, “Let’s move back home to Wisconsin and start a brewery.” Carey launched New Glarus on the strength of the lagers he learned to brew in Germany—a more familiar tipple to the region’s heavily German population—but released Wisconsin Belgian Red, a kriek made with famous Door County cherries, in 1995. It instantly started winning awards (and irritating Belgians), and piqued consumers interest across the country.

None of the Americans knew how to make wild beers, though. This wasn’t a thing they taught you in brewing school, and the techniques weren’t known in the U.S. In the 1990s, lots of people tried to get Carey to explain how he did it, but he guarded his techniques. Beginning in the 2000s, breweries became more adept at barrel aging and pitching wild yeasts. Some experimented with sour mashes and lactic fermentations, and eventually even began exploring spontaneous fermentation. In Maine, Allagash’s Rob Tod embarked on the most audacious journey into the world of wild ales in 2008, when he added a new building and cool ship for spontaneous fermentation; others, like Ron Jeffries at Jolly Pumpkin in Michigan, also played with these techniques.

The Brett Pack. In 2006, a group of five American brewers decided to take a trip to Belgium to see how many secrets they might prize from the methods of the old country. A lot, as it turned out. When they returned stateside, full of inspiration and excitement, each one launched some kind of wild ale program; the brewers now form a who’s who of wild-ale brewing: Adam Avery (Avery Brewing), Tomme Arthur (Port Brewing/Lost Abbey), Sam Calagione (Dogfish Head), Vinnie Cilurzo (Russian River Brewing), and Rob Tod (Allagash). A group of five guys fueled by charisma and beer—on a mission to understand the secrets of Brettanomyces—the name was almost too perfect. But which one is Joey Bishop?

Americans led the way in this revival, but soon brewers from other countries joined in. Belgians, perhaps feeling a bit proprietary about the methods Americans were happily appropriating, were among the first. Craft breweries like De Proef and De Struise jumped in to reclaim their national heritage. But the Italian brewers have most quickly adopted the methods of wild fermentation. In fact, wild beers form a much more central part of the emerging Italian brewing canon than they do in either Belgium or the United States, where wild ales are at most a niche interest. Italian brewhouses like Birra del Borgo, Baladin, LoverBeer, Panil, and Ducato all have been making stellar examples. ■

IF YOU VISIT at the right time of year, you might find flats of apricots stacked around the Cascade Barrel House in Oregon. Brewer Ron Gansberg likes to make a trip down the Columbia River Gorge from Portland to personally select the fruit he’ll put in his barrel-aged sour beer. (He also uses cherries, blackberries, blueberries, raspberries, figs—whatever catches his fancy, really.) But Gansberg, whose biography includes a stint in the wine industry, is a firm believer that Brettanomyces is the bane of good beer. When his hand-selected apricots find a barrel, they’ll encounter only Lactobacillus acidifying the beer.

If, however, you visit the cellars of Chad Yakobson’s Denver-based Crooked Stave, you enter the Sanctum of Brett. A lot of brewers use Brettanomyces in their beers, but no one is as committed to the wild yeast as Yakobson. In brewing school, he wrote a detailed master’s thesis on the famous English fungus and went on to found a brewery where all beers are pitched exclusively with various strains of Brett.

These are but two examples of two brewers, both holding as close to perfectly opposing views as brewers could have. The point is: With wild ales, there are no rules, no general guidelines, no standard practices. To brewers, this is one of the beers’ central attractions. The frontier of tart, acidic beers is tabula rasa and there is no theology to blaspheme. New Belgium’s Peter Bouckaert, a pioneer in barrel-aged beers, says, “If I find a better way to make better beer, I’ll make a better beer.” A Belgian who came to Colorado via Roeselare and Rodenbach, he knows of what he speaks. New Belgium’s system evolved from wine barrels to large wine vats, like Rodenbach, but in Fort Collins they make their famous La Folie using a “solera” system developed by sherry makers. It’s a beer compared to Rodenbach, but the production method is quite a bit different. “What is traditional?” Bouckaert asks. “I’m not stuck in tradition—I’m not a museum. I want to continue to learn.”

Wild ales may be only lightly acidic or puckeringly sour; they may be any strength or color; and they may be made without fruit or, more often, with. The dazzling range of beers and production methods make this vein of brewing very difficult to categorize. It includes a beer called Buddha’s Brew from Austin’s Jester King. The brewery racks raw wort into barrels, pitches yeast and bacteria, and after a gestation period of nine months, bottles it with a fresh infusion of kombucha (a tea made with Acetobacter and yeasts). It is just 4.7% ABV, and the flaxen hue of witbier. The category also includes Cascade’s Bourbonic Plague, a beer aged in three different types of barrels and blended with a separate batch that had been aged with cinnamon sticks and vanilla beans. Blended together, they spend another fourteen months on dates. That beer is 12% and black as an oil slick. And, too, the group includes Allagash Coolship Red (5.7%), a spontaneously fermented beer flavored with raspberries, and Double Mountain Devil’s Kriek (9%), made with the cherries picked from brewer Matt Swihart’s orchards. And … well, the list is hundreds of beers long, and no two are alike.

Wild and aged in bourbon barrels, Cascade’s deep black Bourbonic Plague proves that wild ales defy typecasting.

If there is a proclivity that distinguishes the new wild ales from those brewed in Belgium and Germany, it has to do with strength and intensity. Tart ales are by their own measure “extreme”—at least when compared with standard lagers and ales. American breweries tend to accentuate that by brewing them strong. The best-known examples from Russian River, The Lost Abbey, New Belgium, and Cascade Brewing are mostly stronger than 7%. Moreover, the flavors tend to be bolder than their European counterparts. The Brettanomyces character is drier and more leathery, the lactic acids sharper and more pronounced. Oregon State University measured these qualities when they compared tart ales from Flanders with American beers. Reporting the findings, OSU pilot brewery manager Jeff Clawson summarized the differences this way: “The American beers were perceived as quite a bit more sour, more astringent, more bitter, more salty, more stale/moldy, briny, dusty/earthy. Again, it’s a character the American brewers are looking for.” The Belgian beers, he said, were “less sour, a lot sweeter, lower in alcohol, not very bitter, and just very mellow, easy-to-drink sour beers.”

How Sour Is Too Sour? In one extraordinary twenty-four–hour period, I sampled lambics and gueuzes from the breweries/blenderies at Cantillon, Drie Fonteinen, and Boon in and around Brussels. When I was sitting down to a gueuze from my fourth producer, Girardin, I had a bolt of insight. None of the many different sour beers I’d been drinking was violent. They may have been brightly tart, but the flavors harmonized beautifully. In the United States, where “extreme” is a prized characteristic, tart ales can sometimes pack the punch of a raw habanero.

It should not be so. In many American wild ales, the acidity is as unyielding as vinegar and the “funk” tastes of diapers, burned rubber, and nail polish remover. To stake out a bold position, let me argue that a glass of vinegar that smells like burned rubber and used nappies is a mistake, not a beer. Too often, Americans forgive offensive aromas and flavors so long as they’re suitably loud. Because tart ales contain so many weird flavors, drinkers often think these unpleasant qualities are intentional. Making good beer with wild yeasts and bacteria is one of the biggest challenges in brewing and, done right, produces a beverage almost anyone can appreciate—if not love. The drink will contain unfamiliar flavors and sensations, but they won’t be innately unpleasant. Plenty of American breweries make beers to rival those in Brussels—even more reason we should refuse to tolerate those that don’t.

Hypertartness is not the rule with Italian wild ales, however. It’s a hallmark of Italian brewing that nothing is made to the extremes. With their focus on harmonizing beverage with cuisine, the hoppy ales are never too hoppy, and the wild ales are never too wild. LoverBeer, from just outside Torino, uses local barbera grapes to inoculate the wort—and those cultures have since inoculated the brewery’s small wooden tuns—but the effect is a supple, rounded tartness. Farther east, in Allesandria, Birrificio Montegioco also makes delicate wild ales aged in wine barrels. They can have earthy, savory, herbal, or tropical highlights, and they finish with a tingle, not an electric shock of sour. ■

UNTIL THEY TASTED Dan Carey’s marvelous tart ales, most American brewers hadn’t spent a lot of time considering how to replicate the feat. Once they began scratching around, though, they found a trove of old and really old techniques from decades—and centuries—gone by. They began experimenting. Do you need to make a turbid mash, as the lambic makers do? Some breweries use them (Allagash), others don’t (Russian River). Do you need to use aged hops? What about malted versus unmalted wheat? Personally I don’t know of any brewery that attempted the twelve-hour boils Georges Lacambre described from the mid-nineteenth century (see page 246), but I wouldn’t be shocked to learn they’ve been reprised.

American brewers have different equipment and ingredients, and make ad hoc adjustments to account for the changes in the modern brewery. They have to improvise, and in many cases don’t have anyone to consult. At New Belgium, Peter Bouckaert realized that he was having a problem with yeast accumulation in his foeders. He came up with a clever solution. “Now what we do is a lager fermentation and we then filter the yeast out warm and then put it on wood.” Lagering and filtration—modern innovations they never used in Lembeek.

Russian River’s Vinnie Cilurzo and Lost Abbey’s Tomme Arthur—two Brett Packers—modified their systems for spontaneous fermentation after that fateful trip to Belgium and Cantillon. “That’s when Tomme and I came up with the idea to do the mash tun,” Cilurzo said, “because we didn’t have a cool ship.” After doing a sour mash on Friday evening, he ran the wort out of the mash tun, cleaned it, and returned the wort. “We would … let it sit overnight in the mash tun so it would pick up all the little bugs and critters that [grew] during the sour mash the night before. And then we come in Sunday and pump the beer over to the barrels. Then it would go through a spontaneous fermentation.” (Russian River has upgraded to a stand-alone cool ship.)

Taken together, the techniques used in the United States and Italy form a living museum of wild ale brewing. Following is a short list of the most common methods.

■ Spontaneous fermentation. This is the granddaddy of all wild ale techniques, both the most expensive and the least predictable. Belgian lambic breweries have the advantage of tradition; they have had decades to perfect their techniques. When breweries like Allagash began using completely wild inoculation, they weren’t sure whether the wild yeasts around their breweries would produce palatable beers—and not all of them have. But some—and Allagash is the charter member—have found their local yeasts to be wonderful partners in producing spontaneous beers. Now several American breweries make beer this way—more than do it in Belgium.

■ Spontaneous via media. Wild yeasts and bacteria are airborne, but they also live on the surfaces of objects. Brewers in Belgium speculate that one of the reasons lambic breweries have had such healthy, flavorful yeasts is because the bugs took flight from nearby fruit trees. LoverBeer, in Italy’s northern wine country, decided to skip the airborne stage; brewer Valter Loverier adds yeast-covered grapes straight to his cooled wort instead. This is how vintners sparked fermentation for centuries, and it works for beer, too.

■ Solera. In the production of balsamic vinegar and certain wines like sherry, a solera consists of a series of wooden casks. The solera is a way of progressively aging the liquid; a portion is taken out of each cask at regular intervals and moved to the next cask, which contains an older mixture, so that by the time liquid is removed from the final cask, it contains a blend of aged liquids. In beer production, each cask is its own solera.

The most prominent practitioner of this technique is New Belgium, which has a system of large oak vats from 1,600 to over 5,200 gallons where beer is aged. Some of the vats contain pale base beer (named Felix), others dark (Oscar, of course), and they both ripen for the better part of two years. When it comes time to produce a beer like La Folie, the master blender, Lauren Salazar, begins tasting the lots from different vats and making a mother blend. Afterward, the brewery tops off each vat with fresh beer and the process repeats. Over time, each vat becomes a distinct ecosystem for populations of different microorganisms, and the beer each one produces is unlike the next.

■ Barrel inoculation. Another way of working with native populations of yeast and bacteria is to nurture them in barrels and inoculate fresh wort by putting it in these funky casks. Wineries and breweries used to spend time and money making sure the critters stayed out of the barrels, but this is a way of taking advantage of barrels where they have taken up residence. As in New Belgium’s solera system, each wild barrel will develop its own characteristics.

■ Pitched wild yeasts. The easiest and most common way to introduce wild yeast and bacteria to fresh wort is in the form of laboratory-produced pure culture. American companies like White Labs and Wyeast have cultured different strains, and they are a (relatively) safe way to sour beer. Still, the effects are not predictable: Once introduced into a wooden cask, the effects of oxygen, temperature, and other organisms will affect each batch differently. For brewers who want more control, steel reduces the variables even more.

These are just the most common methods, and they are often used in combination. Cilurzo, for example, distinguishes between the kind of spontaneous fermentation he conducts and the process used in Belgium. “There has been a lot of spontaneous [fermentation] in there, but there have also been a lot of barrels that we pitched. You know, bacteria spilled on the floor.” Those pitched, spilled bacteria and yeasts now inhabit the barrel room and form part of the microbiology of the “spontaneous” environment. Most breweries have similar small modifications in their own processes. ■

THE REINTRODUCTION of wild ales into captivity is less than two decades along. Since the methods of making them had been long abandoned (willfully, in most cases), brewers are still in the formative, tinkering stage. Each year, a brewery comes out with a new interpretation to add to the growing canon. As of this writing, the ratings site BeerAdvocate lists about seven hundred commercial examples—about twice the number of helles bocks and schwarzbiers. The tide has only begun to rise. ■

UNLIKE MOST production beers, it’s nearly impossible to reproduce the flavors in wild ales consistently. This year’s La Folie may be deep with red fruits, while last year’s was heavier on persimmon. More like wine vintages, good wild ales reflect the conditions of the year. The temperature, variety of ambient microorganisms, quality of fruit—who knows, possibly even the position of the moon—all these things will result in gamier or softer or drier examples from year to year.

Fruited ales can be drunk as soon as you find a bottle, while others might evolve for a year or more in the bottle—acidity and alcohol are excellent preservatives, so even delicate fruit aromas remain bright longer in these types of beers. Whenever wild yeasts are involved, beers may continue to change as the vigorous Brettanomyces continues to consume sugars; the beers will become stronger and drier. The “wild” in wild ales is meant to indicate the nature of the yeast, but it could as easily point to the beers themselves. They are not predictable, and drinkers who enjoy this type of beer will have to venture without a map … into the wild.

LOCATION: Fort Collins, CO

MALT: Pale, Munich, carapils, caramel, chocolate

HOPS: Target

6% ABV, 18 IBU

The foeders of New Belgium have decidedly different character from one another, and some of them ripen beer into extremely tart liquids. Brewed very roughly in the mode of Rodenbach, La Folie is more acetic and less lactic than Roeselare’s finest. It also has some dry tannins that make it distinctive. These spikier elements are balanced by a sumptuous sweetness that comes from various blends. It’s not a subtle beer, but with many facets of different sweet, sour, and bitter flavors that produce a different vintage each year, it rewards careful attention.

LOCATION: Portland, ME

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

6% ABV

Resurgam is a blend of brews of different ages, like a gueuze; the batch I tried contained two-year-old, eighteen-month-old, and six-month-old vintages. The mark of Belgian gueuzes is their balance and approachability, and Allagash meets this standard. It is a lemony, peppery beer with a wheat softness and mild acidity. The brewery is working to increase its volume, and Resurgam should continue to evolve in complexity as Allagash has more beer to work with.

LOCATION: New Glarus, WI

MALT: Pale, Munich, wheat, caramel

HOPS: Aged Hallertau

OTHER: Door County Montmorency cherries

4% ABV, 1.052 SP. GR.

I remember when this Belgian Red first appeared, I couldn’t believe how tart it seemed. The market has since pushed flavors to the extreme, and now this lovely little kriek seems a perfect balance of lush fresh cherries dried by acid crispness. It’s the kind of beer even those wary of sourness will enjoy.

LOCATION: Santa Rosa, CA

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

5.5% ABV, 1.050 SP. GR.

Beatification is a beer that seems to vary from the sour to the extremely sour—a sere, leathery sensation that overwhelms even the sharp vinegar notes. It takes a swallow or two to acclimatize the palate, and then a curious thing happens: Beatification opens up with light, springing lemon and grapefruit-rind flavors. Bubbling carbonation invigorates the beer and animates it.

LOCATION: Portland, OR

MALT: Franco-Belgian pilsner, pale

HOPS: Aged Golding

OTHER: Hood River apricots

7.3% ABV, 1.065 SP. GR., 8 IBU

Cascade brewer Ron Gansberg has a fleet of excellent sour ales—Noyeaux, The Vine, Bourbonic Plague, and more—so here we’ll let Apricot stand in for all of them. Gansberg’s careful selection of fruit leads to dense, sweet aromatics and the scent of fruit blossoms. The beer itself, though alcoholic, is light bodied and apricot hued, summery and refreshing. The acidity preserves the fruit flavors and aromas, and there is enough residual sweetness to add body and balance; a Champagne-like spume of bubbles further enlivens it.

LOCATION: San Marcos, CA

MALT: Pale, wheat, light and dark caramel, Special B, chocolate

HOPS: Challenger, East Kent Golding

OTHER: Dextrose, raisins, candi sugar, sour cherries

11% ABV, 1.092 SP. GR.

This beer really speaks of the American craft-brewing instinct. Pushed and prodded to the extremes on every dimension, it is hugely alcoholic and packed with intense flavors that begin as fruit and sugars—cherries for sure, but they have to battle treacle and dark fruit for top billing. The Brettanomyces gives the beer just enough acid for balance.

LOCATION: Dexter, MI

MALT: Pilsner, pale, Munich, dark caramel, black, and wheat malt

HOPS: Tettnang, Strisselspalt

OTHER: Dextrose

7.2% ABV, 1.054 SP. GR., 25 IBU

La Roja takes its inspiration from tart Flemish ales, but is distinctly American. Brewer Ron Jeffries blends one-year-old, six-month-old, and one-month-old beer. Even with the fresher beer, the Brettanomyces turns this to an incredibly dry, stony beer—a more parched presentation than you’d ever find in Brussels. Some nuttiness and wood tannins give it depth.

LOCATION: Normal, IL

MALT: Varies

HOPS: Varies

ABV, SP. GR., IBU: Varies

Dekkera is another name for Brettanomyces, but the ales in the brewery’s series are actually spontaneously wood fermented and contain a lambic-like variety of microorganisms. The beers rotate and change. A sampling I tried in 2011 included a violent framboise but two lovely milder ales, one with strawberry and a tart Flemish that had nutty malt character to balance sharper tart notes and tons of fruity esters.

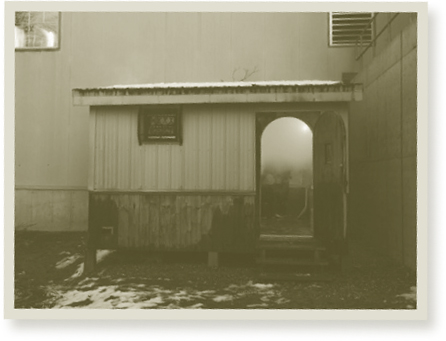

IF YOU WALK AROUND THE OUTSIDE OF THE ALLAGASH BREWERY, AN INDUSTRIAL WAREHOUSE FACILITY IN PORTLAND, MAINE, YOU RUN INTO AN ODD SIGHT—ANOTHER, MUCH SMALLER BUILDING ATTACHED LIKE A RUMBLE SEAT. A PIPE RUNS FROM THE MAIN BREWERY TO A BROAD, FLAT TANK THAT FILLS MOST OF THE INSIDE OF THE LITTLER STRUCTURE, AND DELIVERS WORT STRAIGHT FROM THE BREW KETTLE. THE TANK WILL HOLD THE WORT FOR TWELVE HOURS WHILE WILD YEASTS FROM THE CLEAN MAINE AIR DRIFT THROUGH OPEN WINDOWS AND “INFECT” THE BEER. THIS IS THE MOST ELEMENTAL FORM OF BREWING, MILLENNIA OLD, AND WHEN OWNER ROB TOD INSTALLED THE COOL SHIP IN 2008, HE HAD NO IDEA WHETHER IT WOULD WORK.

When I asked whether they had done any tests to gauge its viability, Tod and head brewer Jason Perkins said nope, that wasn’t really possible. “We considered it,” Perkins said, “but truthfully it wouldn’t have been—well, it might have been partially accurate, but we needed to build the room first. We could have just put a bucket out there in the woods to see what would happen, but it wouldn’t have been the same effect.” They had some inkling the project would work, though. One of the brewery’s barrels had already picked up some wild yeast, and instead of dumping the contents and hosing down the facility, they nurtured it. At first, Tod and Perkins weren’t even certain what it was, but thought the character indicated Brettanomyces. Eventually they had it isolated at Wyeast Labs and found it was Brett. “It was not a strain they’ve ever seen before, different character,” Perkins said. “So it’s resident to this area, certainly. It has since gotten into a couple of our other barrels over time, some of our real long-aging barrels, unintentionally.”

The second factor was the location. They looked at the maps and found that Maine is actually south of Brussels, but despite extremes in the hottest summer and coldest winter months, the weather is actually very similar. “March through June and late October through December, they’re identical weather,” Perkins said.

It was still a pretty radical decision. Tod was a member of the famous Brett Pack of American brewers who traveled to Belgium in 2006. Like his cohorts, he got really excited at the prospect of wild brewing—but later reconsidered. “When I got back I thought, ‘It’s too much work, it’s too risky having all those microbes in the brewery. Let’s just focus on the other Belgian-style beers we do.’” The enthusiasm returned, though, and later on “we all just looked at each other and we’re like ‘F**k it, let’s build a cool ship.’ That was basically what it came down to.”

The gods of brewing smile on Allagash. The Atlantic air that blows across their cooling wort carries a rich habitat of healthy microorganisms that produce excellent lambic-style beer. The wild ales of Allagash are characterized by light and balanced tartness. Like those of Cantillon, they have a bit of lemon rind that adds citrus and bitterness. These Portland wild ales have a balanced acidity with none of the harsh chemical flavors wild yeasts sometimes produce.

In deference to the originals in Belgium, Allagash doesn’t call their beer a lambic—but they could. They use raw wheat malt and conduct something like a traditional turbid mash. Perkins pulls out a portion to bring to a boil in the kettle before returning it, raising the temperature in a Belgian version of decoction. Later he adds aged hops to avoid bitterness and puts the wort through a marathon four-hour boil. Like the lambic brewers in Belgium’s Pajottenland, the wort overnights in the cool ship and then spends months aging in barrels before being blended and packaged. In every way that matters, Tod has re-created a lambic brewery in the United States.

Allagash’s cabin-like cool ship is relatively new, though the process it facilitates is millennia old.

It’s difficult to see how the spontaneous project will generate much in the way of revenue, but that’s the wrong way to think about it. Breweries making this kind of beer, such as New Belgium, Russian River, Destihl, and others, do it because they love the flavors the ales contain. Because spontaneous and wild ales are a small portion of the breweries’ bottom line, they don’t have to pencil out financially. Breweries enjoy making them and customers get excited to buy them—which doesn’t hurt the reputation of the brewery. But there are tangible benefits, too, and more and more breweries are recognizing them. Allagash’s initial dalliance with Brettanomyces was risky and not obviously profitable. Yet it gave them a wonderful yeast they now use in Confluence, Interlude, Gargamel, and others. Their courage has resulted in a ton of good press—none of which hurts the sale of the flagship, White Ale—and their experiments are yielding unexpected possibilities. It’s an exciting time.