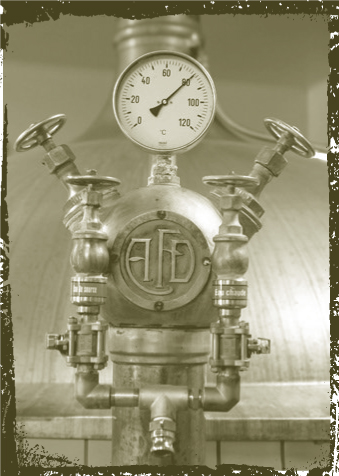

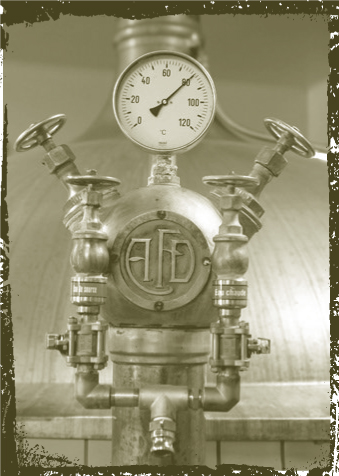

Belgian breweries often have wonderful steampunk gadgets like this.

Any serious explorer into the world of beer eventually has to contend with the complex world of Belgian ales. They reside, like exotic creatures in a dense rain forest, in their own realm, far from their sedate, civilized cousins in nearby Germany and Britain. No country has so many native beer styles, nor has been as tenacious at holding on to them through the industrial age.

Centuries ago, breweries would make a beer typical of their town, one different from those brewed at the next town over. Modern Belgian beers are visible inheritors of that tradition and even today, more indigenous varieties manage to persist in a country the size of Maryland than in any other. Some are sour, some strong, some dark; some are made by commercial brewers, some by Catholic monks. Some are made of wheat, many use spices. Most are defined by a quality that comes from the yeast—a spiciness, fruitiness, or funkiness—that has made the word “Belgian” an adjective of character as much as region. They are so varied that it takes some time to find your bearings, but explore Belgian ales long enough, and you may find other beers look a little monochromatic by comparison. ■

HOW DID A tiny country that didn’t even gain independence until 1830 manage to avoid having its beer tradition subsumed by a dominant neighbor? How did Belgium become the one country with such quirky diversity and enduringly native styles? This is one of the central curiosities of a very curious beer country.

It started with a Belgian love for beer. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus had written that they “make a drink out of barley which they call zythos or beer.” Writing later, Athenaeus described it more precisely as a wheat beer made with honey. Even Julius Caesar encountered and admired the pastoral Belgae tribes, calling them the “bravest of the three peoples” of Gaul. (He was forced to admit that bravery may not have been associated solely with wine-drinking societies.)

The Romans were just the first foreign power to seize the cities of what would become Belgium as part of their empire. Many others followed, and the history of Europe is written fairly well on the land between Antwerp and the Ardennes. Belgium had the distinction of hosting armies from some of Europe’s most famous conquerors: Following Caesar, it saw Napoleon and Hitler, not to mention dozens of minor lords and nobles across the centuries.

Through it all, a familiar pattern emerged: The cities of what would become Belgium flourished, empire after empire. Ghent was at one time the second-largest city in Europe (after Paris), and Bruges, Leuven (or Louvain), and Brussels thrived at various times as well. Antwerp’s port was and remains one of Europe’s largest. When the region was under the control of the House of Burgundy in the fifteenth century, Philip III, Duke of Burgundy, chose to live in Brussels and Bruges rather than France. Mary of Burgundy, whose marriage to the Archduke Maximilian caused the Low Countries to fall under Hapsburg control, is buried in Bruges. (Mary is celebrated by Brouwerij Verhaeghe in their delightful Flanders tart ale, Duchesse de Bourgogne.) So while Belgium finally became an independent state in 1830, it was a relatively stable place for the rise and maintenance of certain cultural traditions—including brewing beer.

Belgian breweries often have wonderful steampunk gadgets like this.

The view of Bruges, possibly the world’s prettiest good-beer city, from the iconic bell tower just south of the Grand Place

After those early Roman references, the historical record went silent about brewing until monks began to write about it again in the eighth and ninth centuries, as ecclesiastical power grew across Europe. Monasteries flourished during the period and maintained lives of self-sufficiency. They grew their own barley (and later, hops) and made beer to serve themselves and visitors. Records show that some of their breweries were immense operations for the day, able to produce as much as a modern craft brewery.

Unfortunately for us, only scant references to Belgian beers describe their subsequent evolution between the ninth and nineteenth centuries. Stray observers did make oblique references, so we know that Belgians brewed with wheat, oats, and spelt in the late Middle Ages. This conforms well to an extensive survey of Belgian beer by a brewer named Georges Lacambre (sometimes rendered La Cambre) whose Traité Complet de la Fabrication des Bières was the first serious treatment of traditional Belgian brewing. Lacambre worked at a brewery in Leuven in the 1830s and his work expanded on writings done earlier in the century by two men, J. B. Vrancken and Auguste Dubrunfaut. What this book, first published in 1851, details is an absolutely extraordinary world of brewing—great diversity on the one hand, with village-by-village variation, and inconceivably baroque brewing methods on the other.

Lacambre catalogued around twenty different types of beer (he found many more, but only wrote about the “major” ones). Of these only three specifically called for all-barley recipes. Breweries used oats in more than half the styles, and wheat even a little more often. They used spelt more rarely, but it was the basis for at least one style of beer. The tax laws encouraged them to use strange mashing practices, but this was hardly the only methodological oddity. For bière blanche de Louvain (wheat beer of Leuven), Lacambre had to spend six paragraphs describing the mashing regime, which required five vessels, baskets and pans to strain and spoon out wort, and “eight to ten strong brewers” to manage the ordeal.

Boil length was just as shocking. The average boil was nine hours. Only four of the beers Lacambre mentioned had boils of three hours or less, and five were more than ten hours; the longest was twenty hours (!). In some cases, the long boils were intended to darken the wort; for dark beer styles, this was a mark of wholesomeness. But the breweries had a cheat—they added the mineral lime if they wanted to save some time and darken the wort artificially, a practice of which Lacambre rightly disapproved (“very detrimental to the interests and even the health of consumers”).

Finally, a key to the character of all the beers was the way in which they were cooled. Instead of using cold water chillers, as was the practice in Britain, breweries left the beer overnight in wide, flat vessels known as “cool ships.” This is still the way lambics are made, and we now know that wild yeasts inevitably infect wort cooling over the course of hours. In most cases, breweries would also pitch yeast into the cooled beer before racking it to casks. But it didn’t matter—the beer was already inoculated. The consequence of this is implicit in Lacambre’s description of beer that was aged any time at all—it was dry and sour from those yeasts.

Nineteenth-Century Belgian Taxes. One of the keys to understanding Belgium’s ales is a bizarre nineteenth-century tax law. Rather than levy a fee based on the amount of beer produced or the strength of the beer, the government tax was assessed on the size of a brewery’s mash tun. This is one of those cases in which a single law had a profound effect on the development of beer. The way breweries responded, of course, was to use tiny mash tuns—no matter how much beer they were brewing. To get some kind of efficiency out of their wee tuns, brewers used extremely thick mashes; after they had packed as much grain as they could inside, it left little room for water. As a consequence, breweries had to draw their mash water off and add new water to the grain bed several times for every batch. The legacy of this law is still evident in the turbid mashes lambic makers use.

Beers of Nineteenth-Century Belgium. One wishes there were more historical tour guides like Georges Lacambre. A working brewer, he was not without prejudices and opinions. He discredited certain styles of beer—some he even admitted were renowned—and offered biting commentary about the methods of other brewers. But this lack of objectivity makes for lively and engaging reading. Following are a few of the old beers he described.

UYTZET (UITZET) One of the famous beers Lacambre derided, uytzet came in two strengths, ordinary (about 4% ABV) and double (6% ABV). “Uytzet is an amber beer, fairly dark yellow, and is very good quality when well-prepared, but ordinary uytzet usually has a characteristically dry and more or less sharp taste.”

FLEMISH BROWN BEER This is the beer boiled up to twenty hours; it’s similar to uytzet but darker. Locals loved it, and for this reason Lacambre begrudgingly admitted it might be an acquired taste. For his purposes, though, it was “far from being very pleasant indeed, for it is bitter, harsh, and astringent.” Its descendants are still made in Flanders.

LEUVEN BIÈRE DE MARS, ENKEL GERST, AND DOBBEL GERST The beers Lacambre made himself, and it’s no shock to learn that he thought they were the best. They were made from all-barley grists and divided into four runnings of the same mash. The first two made dobbel gerst, the final two bière de Mars, with enkel gerst being a blend of all four.

WHEAT BEER OF LEUVEN (bière blanche de Louvain) This beer went through an inordinately long and convoluted mash regime, but Lacambre seemed to like it. He described Leuven wheat beer as light and refreshing—something like a cross between lambic and witbier.

PEETERMAN This beer style survived into the 1960s, but based on Lacambre’s description, one wonders how. It was similar to Leuven wheat beer, but brown and made with gelatin usually taken from fish skin. Tasty! Lacambre: “viscous, dark brown, and has a slightly penetrating and aromatic bouquet.” Aromatic indeed.

BIÈRE DE DIEST This was a strong golden ale that, from Lacambre’s description, sounds delicious: “Its creamy flavor is slightly sweet and has something honey-like that is highly sought after by connoisseurs, among which we must count the majority of women and especially wet nurses who [are looking to] find a drink that is comforting and nutritious.”

MECHELEN BROWN BEER Another possible precursor to the tart ales of Flanders.

HOEGAARDEN BEER From Lacambre’s description, this sounds very much like a lambic. Unlike lambic, though, it was served fresh, not aged, apparently to great effect. Lacambre: “This beer is very pale, refreshing and strongly sparkling when it is fresh; its raw taste has something wild that is similar to the Leuven beer it resembles in many ways.”

LIÈGE SAISON A beer often made largely of spelt and aged from at least four months up to two years. Lacambre didn’t like the brewing methods and seemed to regard this as a crude beer whipped up by bumpkins. He said that in the summer, the poor drinkers in Liège drank “more bad beer than good.”

The world wars were difficult for Belgium—particularly the first. Belgium was ground zero for fighting, where some of the biggest battles took place, and where trenches scarred the countryside. The Germans systematically collected all the copper in the country for the war effort—to this day, no kettles date to before about 1920. Belgium rationed grain, and already-low gravities fell even further. After World War I, brewing rebounded and beers returned to form. Gravities recovered and beer quality improved. Things took another dive in the Second World War, when under German occupation, Belgians endured food and fuel rations. But after the war, the brewing industry again rebounded and brewers started making beer as they always had.

By the 1950s, many of the styles Lacambre described still had a presence. Writing a hundred years after Lacambre, Jean De Clerck, a brewing professor at the University of Louvain, made another extensive survey of the world of brewing in A Textbook of Brewing (1957). Among the styles he lists are many of those mentioned by Lacambre—blanche de Louvain, Peeterman, Diest, uytzet, Antwerp barley beer, Hoegaerde, and Liège saison, to name a few. These “old-fashioned” beers were still made in shockingly old-fashioned, complex ways (it took seventeen hours to complete the mash for Peeterman). Sadly, he was recording the last days of many of these styles. Lagers and modern ales were making an assault on the market, and funny little country breweries could no longer stay in business by putting out rustic and wild nineteenth-century beer. They may have outlasted the wars, but they couldn’t survive a modernized brewing market.

Frank Boon, maker of the eponymous lambic, came from a family of brewers and recalled this period from his youth:

In the 1950s and 1960s, breweries were closing and all the local styles were disappearing everywhere in Belgium. Leuven white disappeared, Peeterman disappeared, uytzet disappeared. I remember my uncles said that in the summer they could keep their beer for two weeks. Midsize breweries had beer that could keep one month or six weeks. In the 1960s, Stella Artois was the first to make beer that could keep for six months. Consumers switched to cheaper and technically better beer. In every village and small town, brewers said, “The only thing we can do is sell the brewery. There is no future for small breweries.”

The Drinking Ritual. The way a country consumes its beer offers subtle clues to the kind of beer it produces. In the United States, for example, the overwhelming majority of people buy their beer by the case and slug it back straight from the can. The overwhelming majority of beer is consequently made to enter the stomach by attracting as little of the tongue’s attention as possible on its way down.

The way Belgians serve beer reflects the country’s more refined approach: They savor each sip of their fine national beverage. When you order beer in a beer café, the waitress will bring you the bottle of beer along with a glass made specially for that beer. (Belgian ales are almost all bottle-conditioned, and therefore sold in bottles.) She will decant it for you into the glass, pouring it at a rate to ensure the perfect, pillowy head. She will stop pouring with a half inch of beer remaining (the portion that will have become clouded by roused yeast) and place the bottle next to the glass, rotating it so you may inspect the label. In Belgium, drinking a glass of beer is a sensual experience. The way the beer is made, the color and carbonation, the glassware—all these things are optimized to delight the eyes, nose, and tongue.

As was the case in every other country in the world, consolidation hit Belgium hard. The country had well over 3,000 breweries in 1900, a number that dwindled to less than a thousand by the middle of the century. Most countries hit their low points in the 1970s, but Belgium’s came in the 1990s, when there were just 115 breweries left. In the end, Belgium was left with two titans and a scattering of small family breweries.

The largest of the titans was Interbrew, a company that started to dominate the Belgian market in 1987 when Artois merged with Piedboeuf (makers of Jupiler). Soon after, Interbrew acquired Labatt, Bass, Whitbread, and Beck’s. Ultimately, it would merge with Brazil’s AmBev and finally take over Anheuser Busch to become InBev, the world’s largest brewing conglomerate. Hoegaarden, Leffe, Belle-Vue, Jupiler, and Stella Artois are all owned by InBev, and their pubs can be found everywhere from the Brussels airport and beyond. The world headquarters are now located in Leuven.

The Gauloise was the first beer brewed by du Bocq, in 1858.

At one point InBev (then Interbrew) controlled 70 percent of the Belgian market, but that figure has receded to below 60 percent due to the rise of a rival, Heineken. The Dutch giant entered the Belgian market forcefully in 2000 with acquisitions of Affligem and Alken-Maes, bringing a number of major brands under its portfolio: Grimbergen, Maes Pils, Ciney, and Hapkin. These compete for pub space with the InBev juggernaut, an arms race that smaller breweries simply can’t begin to match.

The Belgian beer industry is now in a moment of transition. The international craft beer movement has pumped a little life into the market, but the number of Belgian breweries remains near historic lows. Meanwhile, InBev and Heineken have successfully concealed the provenance of many of their brands—making it harder for small ale brewers to compete locally. As a countervailing trend, the rest of the world has awakened to the genius of Belgian beers. The export market is keeping many small breweries afloat, but the erosion of the home market is troubling. InBev and Heineken will attempt to consolidate as much of the market as they can, but Belgian consumers are fond of their local brands. The next decade will be crucial for the future of Belgium’s beers. ■

BELGIAN BEERS COME in a spectrum of colors and strengths, though they’re not fixed. There is constant churn and change, as trends drive producers in one direction for a time before they set off in a different direction a decade or three later. Old-timers lament the loss of traditional styles or what they claim is a dumbing-down of certain famous brands, and no doubt that happens—but they ignore how other old brands have spruced themselves up and how new breweries have helped usher in new styles. In Belgium, change is the constant.

Over the decades, Belgian ales have gotten more potent and lighter in color. Among the most popular styles now are blond or golden ales—a minority even a generation ago—and of these, there are silky, potent tipples that rival wine in strength. Hops are making a comeback, and many breweries have embraced organic brewing. But these are broad contours; Belgium is proud to tout a thousand different brands, and dozens of them are beyond the reach of style taxonomists.

What should you expect in a Belgian ale? Their reputation for quirkiness has scared off a good many beer fans, but this is largely misplaced. The sour ales are generally an acquired taste, but most Belgian ales are quite approachable. Here are four things to look for.

■ Fermentation characteristics. Belgian beers are fermented warm, a practice that produces interesting phenols (spicy) and esters (fruity and spicy). It is a nearly ubiquitous practice in Belgium to referment beers in the bottle, and this enhances those qualities.

■ Light body. Sugar is a very common ingredient. Breweries use it to thin the body, boost alcohol percentage, and balance low-hop beers with crispness.

■ Strength. Belgian ales run the full spectrum of strength, but no country has so many beers tipping the scale above 7% ABV.

■ Spices. Belgium’s reputation for spicing is overblown; they are employed in a relatively small minority of beers. The nature of Belgian ale is one of fruitiness and spiciness; the addition of actual spices enhances this character. In some cases breweries don’t even mention they’ve added them. The key to a Belgian ale depends less on whether actual spices are used than on how well the fruity, spicy notes express themselves.

Amber ales date back centuries in Belgium and were once a much larger part of the brewing scene than recent-arriving blonds. For centuries Belgians did not covet blond ales—even after breweries knew how to make pale malts. Deeper colors of amber and brown were the sign that a beer had been boiled a good long time and caramelized during the process—qualities prized in a beer. There are still several classic examples around, like De Koninck Amber, Dubuisson’s venerable (and powerful) Ambrée, and Caracole’s rustic flagship, also called Caracole. This group gives you a sense of how broadly this category can range, too. De Koninck’s beer is a mere 5.2% ABV and has a lightly malty palate enlivened by gentle fruity esters. Caracole’s more rustic version is a hearty 7.5% ABV, and has a spicy bouquet mixed with wild strawberry esters and a bit of dry tang from the yeast. Dubuisson’s ale (sold as Scaldis Amber in the U.S.) is a booming 12% ABV with tons of nutty malt and alcohol warmth.

Reading a Belgian Beer Label. Belgian beer labels may contain descriptions in English, French, or Flemish. Here’s a handy reference of what they’re telling you.

FLEMISH |

ENGLISH |

FRENCH |

hergist in de fles |

bottle-conditioned |

sur lies |

kruiden |

spices |

épices |

gerst |

barley |

orge |

mout |

malt |

malt |

tarwe |

wheat |

blé |

hop |

hops |

houblon |

suiker |

sugar |

sucre |

gist |

yeast |

levure |

kriek/krieken |

cherries |

cerises |

frambozen |

raspberries |

framboises |

The lager wave was very late in hitting Belgium, arriving only in the 1960s, but when it did, very pale ales were the ale brewers’ response. It’s safe to say that the most important early pale ale was made by Moortgat. The brew-ery’s flagship beer, Duvel (pronounced DEW-vul), had for decades been a more traditional amber. In 1970, Moortgat decided to follow the market and lighten its beer. Working with Jean De Clerck, the scientist who consulted with Chimay, Rochefort, and Orval, the brewery transformed Duvel into a luminous golden ale. The name is derived from the Flemish word for “devil” and long predates the current incarnation; nevertheless, the beer’s incredible silkiness, balance, and Champagne-like effervescence today make the name more apt than ever. The devil’s power is his sneakiness, his ability to corrupt before the sinner knows he’s sinned. At 8.5% ABV, Duvel drinks like it’s half that, and more than a few people have been seduced to drink too much.

It is a huge credit to Moortgat that the blond they settled on is so rich in esters and hop character. Duvel illustrated to other breweries the possibilities in blond beers—and over the decades, they’ve had great fun reinventing the wheel. Blond beers are now legion, but some high-water marks include an amazing “session” blond by the monks of Westvleteren (it’s 5.8%), which has a touch of handmade rusticity. Dupont’s reputation within Belgium rests on their Moinette, one of the oldest pales in the country. A lighter blond that has zest and character is Brugse Zot from De Halve Maan. In the United States, Ommegang’s Belgian Pale Ale is a spritzy, hoppy treat. These give a sense of the broad range of what a blond or amber can be in Belgium—weak to strong, sweet to hoppy, they’re all part of the family.

The writing is on the wall—the Flemish translates to “Shhh, here ripens the Duvel.” As Duvel is a reference to the devil, it has a darker sense as well.

Brown ales were once highly prized across Flemish-speaking Belgium. Decades ago, they all had something of the character that the tart ales of Flanders—Rodenbach, Liefmans, Verhaeghe—still have. But modernity allowed breweries to escape souring microorganisms, and browns evolved into hearty, often very strong beers not totally unlike British stouts and porters. Brown ales are not as popular as they once were, but they remain an important part of Belgium’s heritage.

One of the touchstone browns is Du Bocq’s Gauloise Brune, its evocation of “la bière de nos ancêtres”—the ancient beers of Belgium. Du Bocq has brewed the beer since 1858, but has changed the recipe. Some old hands criticize Du Bocq for bowdlerizing Brune, but it still has a lot of character, with bread, roastiness, and rummy burned sugar all working in harmony. Perhaps Du Bocq’s critics aren’t satisfied with a beer that’s only 8.1%—maybe they cotton more to the likes of Caracole’s Nostradamus, a 9.5% spicy behemoth. You can’t blame them—it’s a wonderful warmer for the winter months.

Abbey Road. The monastic tradition is an important one in Belgium and has inspired a number of nonmonastic imitators. Two of the most important abbey ale styles are tripel, which is similar to Duvel, and dubbel, a type of brown ale. Those beers are not actually different from the blonds and browns discussed here, but they have a rich tradition all their own. As such, they are treated to a separate chapter (Abbey Ales, starting on page 297).

Caracole’s Nostradamus is a spicy 9.5% ABV.

A classic of the style is the flagship from Het Anker, Gouden Carolus, leaning much more toward sweetness than some examples. As a contrast, one of the best examples is a lightweight, Kerkom Bink Bruin (just 5.5% ABV). It has, nevertheless, a deep cacao character and a biscotti-dry finish. These beers share some qualities but show that disparate elements like spice (Caracole), roast (Gauloise Brune), and sweetness (Gouden Carolus) are all part of the brown ale lineage. Bink Bruin shows they don’t have to be boozy, either.

A Warning About Belgian Beer Styles. Belgian beer is hard to classify. A few styles have extremely rigid definitions; these protect the traditional production methods of beers like gueuze and the tart ales of Flanders. A few other clusters of beer are tight enough to conform to style—beers like witbier, tripel, and saison (all of which are treated separately in this book). Far more fall into a netherworld of stylistic no-man’s-land, and for these, it’s best to abandon the framework of style altogether. The beers may have designations that suggest taxonomy—blond, brown, pale ale, and so on—but they’re mirages. Breweries use them to distinguish their own beers, to give the customer a general sense of what to expect, or for reasons inscrutable to the casual observer. They aren’t indicative of actual styles as the rest of the world understands them.

Indeed, Belgian breweries tend to think of their beers as singular creations, wholly original and uncategorizable—or at the very least they try to get you to think so. This impulse toward individuality makes it very hard to group them in meaningful ways, but it is possible to group them into broader categories.

Europeans all share the tradition of making special beers for the dark months of winter, and especially festive ales for the holidays. In Belgium, these beers are among the most highly anticipated, and a recent tally put the number of offerings at close to a hundred—in a country with only 130 breweries. Belgians love their bières de Noël.

Although it’s not uncommon for breweries to tuck spices into their regular ales, Christmas beers almost demand it. They’re a good example of how adept Belgians are at using spices to accentuate the esters and phenols their yeasts produce. Fans of St. Feuillien wait every year for their Cuvée de Noël, a quintessential winter ale. Dark and warming (it’s 9%), it marries winter spices (the brewery guards its recipe, but my palate detects ginger and cinnamon) with a roasty, chocolaty body. The stiff dose of alcohol provides warmth. Huyghe’s Delirium Noël uses seven spices in a beer bursting with zesty fermentation characteristics that combine to create a somewhat dizzying wall of flavor.

Not all winter ales are spiced, though—some just suggest spicing with their yeast complexity. One of the finest brewed anywhere is De Dolle Brouwers’ Stille Nacht, a light-colored ale with a bouquet of esters and an intense, long finish. Dubuisson Bush de Noël, sold as Scaldis in the United States, is another tremendous unspiced ale. It’s amber-hued but no less powerful (12% ABV).

On the other hand, not all spiced beers are Christmas ales, either. Some styles call for spices (witbier), or use them to accentuate spicy yeast character (rustic ales), or use them as unidentifiable accents (as Rochefort does). Breweries like St. Feuillien use them so skillfully in their ales that it is difficult to tell which element of the spicy flavor comes from the yeast and which comes from actual spicing.

It is not wrong to characterize Belgium’s beers as “sweet” relative to the beers of other countries. Most exhibit modest hop character—not much bitterness and only subtle contributions to flavor and aroma. This proclivity toward sweetness is partly a matter of tradition, and partly a reaction to sodas, which have taken a sizable chunk out of beer’s market. It’s also partly because Belgium’s ales are brewed light with sugars that ferment out completely. Since hops can easily turn vicious in a beer with a light body, fortified with only a small amount of residual malt sugars, Belgian ales typically use less hops than other ales. And, with the crispness and strength they get from sugar, these beers need less balancing hops, anyway.

Hops are grown locally, though, and some breweries have taken greater advantage of them. Located in Watou, a village within Belgium’s hop-growing region, the Van Eecke Brewery is a perfect example. Made with local hops, their Poperings Hommelbier is halfway between an English strong ale and an older, more rustic kind of Belgian ale. It’s a strangely delicate 7.5%, and the hops provide a lacy, spicy bitterness with wildflower aromas.

The trend to sweetness has provoked a small rebellion, and hops are starting to play a larger role in Belgian brewing. At the forefront are newer breweries that have no doubt been influenced by American craft breweries. Their interpretations are revealing, though. One of the best young breweries in Belgium is Brasserie de la Senne, makers of two hop-infused ales, Zinnebir and Taras Boulba. Yet both are distinctly Belgian. Unlike American and English hoppy beers, which have heavier, caramel-inflected palates, these are lighter, crisp, and effervescent. The brewery’s yeast strain has the qualities of a saison—peppery and rustic—that are perfect for the spicy, grassy hops that power these beers.

Another craft brewery focused on hops is De Ranke, producers of the aptly named XX Bitter. Much like the beers of Senne, this one is light-bodied. The effect is an even more profound bitterness; although the brewery uses gentle Brewer’s Gold and Hallertau hops, the bitter result is nevertheless nearly lacerating. There’s nothing like these beers in the American or English tradition. (American hopheads love De Ranke.) Other breweries have tried their hand at hoppy beers, some with notable success, as in Gouden Carolus Hopsinjoor, a beer gently garlanded by flavorful, peppery hopping. Other efforts have been less successful. In Triple Hop, for example, Duvel uses far too much kettle hops for such a light-bodied beer, and the result is punishing bitterness. ■

Local hops give Poperings Hommelbier a wildflower aroma.

BELGIANS EMPLOY A lot of strange and wonderful methods in the brewhouse, but most of the real exotica is covered in the chapters on lambics and the tart ales of Flanders (starting on pages 494 and 514, respectively). When they set about making a straightforward ale, the process is—for Belgium—also pretty straightforward. Brewers typically use step mashes and a large percentage fortify their beer with sugar or cereal grains. The first time I encountered a cereal cooker, it was at the Palm Brewery in Steenhuffel. The technique isn’t ubiquitous, but accepted—even very traditional breweries like Rodenbach use one, and the practice dates back to a time when grains were taxed at different rates. The effect of cereal grains is much the same as sugar—they fortify the beer, giving it a lighter body, more alcohol, and a crisper finish.

As Belgium’s breweries modernize, more and more use the standard cylindroconical fermenters employed throughout the world, but some still rely on square or open fermenters. Many artisanal brewers let their beer rise in temperature as it ferments and cap it at a level ideal for the house yeast strain. The temperature range is impressive and may go into the eighties or even nineties Fahrenheit. This is where the ales form their characteristic fruitiness and spiciness. Many breweries allow their beer to “lager” for days or weeks after primary fermentation to smooth out.

The final, nearly universal step is bottle-conditioning—this is, in many ways, what distinguishes Belgian ales from those elsewhere. Breweries store the beer for weeks—four seems typical—in a “warm room” (around 60°F) to ripen. This is the last stage of a Belgian ale’s chemical evolution, and the beer won’t be complete until the second batch of yeast has had a chance to add its character. It’s an additional advantage for distant Americans; bottle-conditioning is the best way to preserve beer, so ales arrive in the United States in much the shape the brewers intended. British, Czech, and German beers do not always fare as well. ■

The Cereal Cooker. This contraption looks likes the mash tun’s little brother. Indeed, it works like a mash tun, too, except that it’s reserved for unmalted cereal grains like rice and corn. The grains are boiled in the cooker, a process that gelatinizes them and prepares them for conversion by enzymes they lack. Once they’re ready, the cereal grains are added to the regular mash. Here, aided by the rich enzymes in barley, they are converted into fermentable sugars.

BELGIAN ALES have always been in flux, and that remains the case. With the increasing popularity of lagers, Belgian brewers have become a bit morose about the future of small, traditional, or family-owned companies, noting that the giants at InBev and Heineken, having taken 70 percent of the market already, are sneakily trying to seize the remainder with brands like Grimbergen and Leffe.

All true. But things aren’t quite so bad in Belgium. There are still scores of family-run breweries many decades or even centuries old, and a modest crop of craft breweries that are devoted to traditional brewing methods. Meanwhile, the rest of the world has fallen in love with Belgian ales, and the export market is booming.

All of this has had two large effects. On the one hand, it has helped shore up sales for expensive, traditional ales, helping to preserve some of the most interesting breweries. It has also sparked a huge upsurge in the production of Belgian-style ales outside Belgium. The United States and Italy are leading the pack on the trend, and Scandinavia and the Netherlands are not far behind. Even some British breweries have tried their hands at Belgian ales.

Belgian breweries need not fear the competition. Far from challenging Belgian products, these foreign-brewed ales have introduced people to the joys of Belgium and helped expand the market. As more and more people learn about the wonderful world of Belgian ales, that market will continue to grow. ■

St. Arnold and Gambrinus. Two figures stand tall in Belgium’s history and hagiography: Arnold, a brewing saint, and Gambrinus, the king of beer.

Arnold, a brewer’s son, was born near Oudenaarde in 1040. He began life as a knight, but “saw the light” (his words) in his thirties, converting to a life of God. In 1081 he became abbot at the Saint-Médard Abbey in Soissons, France. Among the miracles attributed to Arnold during his beatification was that he plunged his staff into a brew kettle, thus curing everyone who drank the beer of the sickness from water contamination that had been plaguing the area. In retrospect, this looks a lot more like the work of sterilizing heat, but no matter. Arnold was canonized and is now widely celebrated by brewers throughout Belgium.

Gambrinus’s story is more prosaic. The duke of Brabant and Lorraine during the early thirteenth century, his principal accomplishment was allowing local mayors the right to grant brewing licenses. His fame seems to be built more on his avid love of and very public consumption of beer. Gambrinus was once declared the honorary head of the Belgian Brewers’ Guild, and in his memory, the Guild now offers the Chevalerie du Fourquet des Brasseurs (knighthood to the brewer’s fork) to beer-promoting honorees.

I CAN THINK OF no more daunting task than producing a short list of excellent Belgian ales. A list of a hundred wouldn’t have an average beer on it. Consider the following options a starting place. The best way to get to know these beers is by stocking up and sampling them. It could be a lengthy task, but one you’ll enjoy the whole way.

LOCATION: Breendonk, Belgium

MALT: Pilsner

HOPS: Saaz, Styrian Golding

OTHER: Dextrose

8.5% ABV, 1.069 SP. GR., 32 IBU

Duvel gets my vote as the world’s most beautiful beer. The pilsner malts are harnessed so that they glow golden in a tulip glass; meanwhile, an amazing plume of bubbles flashes as they roil from the glass’s bottom. Duvel’s yeast is legend; it produces enormous carbonation and an impossibly tight snow-white head. The secret to Duvel is its balance—creamy and pinot gris–sweet at the front, but surprisingly peppery with layered hopping. Those 32 IBU go further in a sleek, unfettered glass of Duvel than they would a heavier pint of American pale ale.

LOCATION: Cooperstown, NY

MALT: Pilsner, pale, Munich, Belgian Aroma, caramel

HOPS: Columbus, Styrian Golding, Cascade

6.2% ABV, 1.056 SP. GR., 21 IBU

Since its founding in 1997, Ommegang has been committed to re-creating authentic Belgian-style ales (and the founders even recreated a Belgian-looking brewery). BPA almost plays it straight. The beer has the yeast character and complexity of the source beers, but it is slightly heavier in body (no sugar) and those peppery notes give way to the unmistakably floral aromas and flavors of the Cascade hops. Actually, Belgians would totally approve.

Is there a city more romantic than Bruges in which to enjoy a beer?

LOCATION: Brussels, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

4.5% ABV

If Duvel is deceptive by appearing lighter than it is, Taras Boulba misleads for the opposite reason: It’s a tour de force for a beer so light in alcohol. It is no less violently carbonic than Duvel, and its white head is as thick and well-structured as whipped egg whites. But it’s the aroma, thick with pepper and lavender, and the flavor, with an almond note to complement cracker and spice, where the beer astounds. It finishes bone dry, like a saison.

LOCATION: Bruges, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

OTHER: Brewing sugar

6% ABV, 1.055 SP. GR., 26 IBU

Belgium is not known for sessionable beers, so Brugse Zot is a welcome outlier. It’s a light, soft beer, hazily golden with a delicate floral nose and wildflower palate. The beer’s finish has just a twist of citrus to make it crisp and refreshing.

LOCATION: Achouffe, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

OTHER: Coriander, brewing sugar

8% ABV, 1.065 SP. GR.

Known for its charming, silly garden-gnome mascot, La Chouffe gets respect among connoisseurs for its complexity. A perfect example of smoothness in strength, La Chouffe is all sweetness and spice—Meyer lemon and orange, coriander and lavender—and nothing to suggest its power.

LOCATION: Ingelmunster, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

7% ABV, 1.057 SP. GR., 20 IBU

Amusingly, Van Honsebrouck styles this a “low-alcohol content” beer. It’s a relative term (two other Kasteel beers are 11%), but also hints at what you’ll find—a very delicate, light beer. This is a good ale to test-drive for esters, as well; it has tons. I find honey and apple, banana and bubble gum, and perhaps some sherbet for good measure.

LOCATION: Sint-Truiden, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

5.5% ABV, 1.048 SP. GR., 35 IBU

Brouwerij Kerkom has a knack for making revival beers that taste like rustic ghosts from the past. Bink Bruin is not one of those beers—it’s a modern interpretation with filtered clarity and clean lines. The nose and palate have cocoa and plum notes made spicy and grassy by fairly stiff hopping. Despite its low gravity, the beer tastes rich and finishes with a refined, dry snap.

LOCATION: Mechelen, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Belgian-grown

OTHER: Dark sugar

8.5% ABV, 1.074 SP. GR., 16 EBU

Het Anker casts its lineage back to the great tradition of its hometown, Mechelen. Even the name, Gouden Carolus, refers to long-lost local coinage. The historical Mechelen beers were brown, and so is Gouden Carolus. Fermented warm, it has a huge banana-bread nose and a very sweet, fruity palate. The alcohol is well concealed behind an ester-rich frontal assault. A very sweet beer that works best as an aperitif.

LOCATION: Falmignoul, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

9.5% ABV

An enormously fluffy head tops this beer, and it manages to stay put until the final drop—remarkable in beer of this strength. Between pour and final sip are flavors of hazelnut and caramelized sugars. Caracole uses an open flame in their kettle to produce these flavors—one of the few breweries left in the world that does so—and amazingly, it’s still wood-fired. A rich, satisfying beer that’s ideal for colder months.

LOCATION: Watou, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

7.5% ABV

Hommelbier has a rustic look about it—caramelized, orangey, and a little hazy. That first impression is accurate; Hommelbier could easily be called a saison. It has a cakey body and layered flavors of lemon, wildflowers, and honey. The strength is concealed completely, and you have to be careful not to slug it back in hearty, appreciative gulps.

LOCATION: Wevelgem, Belgium

MALT: Pilsner

HOPS: Brewer’s Gold, Hallertau

6.2% ABV

This is a beer that divides people, but everyone can find it instructive—it illustrates how Belgian hoppy ales deviate from the American tradition. In American brewing, hop bitterness is generally buttressed by rich hop flavor and aroma and at least some buffering malts. By contrast, in XX, De Ranke has a beer that is almost purely bitter, a tincture with very little residual sugar. Beyond its defining bitterness, XX is very dry and efferves-cent, qualities that add to the prickliness. Inspired by North American hop bombs, it is nevertheless rendered with a perfect Flemish accent.

LOCATION: Le Rœulx, Belgium

MALT: Pale, caramel, roasted malt

HOPS: Undisclosed

OTHER: Undisclosed spices, dextrose, maltose syrup

8.5% ABV

Cuvée de Noël is the most overtly spiced of St-Feuillien’s spicy line, but even so, it’s a blended, modest potpourri, helping to draw out roasted notes from the darker malts. The flavors conspire to create the impression of chocolate, but the dry finish keeps Cuvée de Noël from cloying.

LOCATION: Esen, Belgium

MALT: Pale

HOPS: Whitbread Golding

OTHER: Solid candi sugar

12% ABV, 1.092 SP. GR., 32 IBU

The name means “silent night,” and De Dolle Brouwers releases this beer for the Christmas season. Stille Nacht goes through a very long boil, caramelizing the malt to produce a deep amber color and a beer of great effervescence. The yeast has a heyday with this massive beer, and there are lots of stone fruit and citrus notes. The brewery slightly acidifies the beer, which dries it out and preserves it. An ideal beer for aging.

LOCATION: Pipaix, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

OTHER: Brewing sugar

12% ABV, 1.101 SP. GR., 25 EBU

This was one of the first Belgian ales I ever tried; I was transfixed by the sparkly little bottle. Inside I discovered the world of Belgian brewing, and it took my breath away. It is a very dense beer, rich with the dried-fruit flavors of malt. The alcohol soaks the malts like a rum cake, and the finish is sweetish, like a ruby port.

LOCATION: Brewed by Du Bocq in Purnode, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

8.5% ABV

Corsendonk has decided that at Christmas, everyone gets what they want. In this case that means a beer that satisfies all tastes: a bubbling, sweet, spicy, and strongly warming winter tipple. Pull out a bottle and people will nod sagely and say “Belgian.” It has all the hallmarks—a thin and wildly effervescent body, very fruity and sweet, and a bit of spice for the season.