Traveling to wine country is such a well-established practice that it has its own name—enotourism. Anyone traveling to Scotland at least considers the idea of stopping in at a whisky distillery. For reasons good and bad, breweries seem to have a weaker magnetic pull. To the extent that breweries are less artisans of place than are vintners and whisky distillers, it makes sense. There’s not a lot of terroir exerting its influence at the average brewery. On the other hand, there are some very good reasons to visit the places where beer is made.

Here’s an example or three. The Brussels air turns chill in October, reliably so in November. That’s when lambic brewing starts. If you watch the Facebook page of Brasserie Cantillon, you’ll notice what appear to be obscure updates: “Next brews on Tuesday 19th and Thursday 21st.” These are actually subtle invitations to fans to drop by the brewery and see brewer Jean Van Roy in action. And in Pilsen, an hour and a half by train from Prague, you can sample wood-aged lager in the cellars beneath Pilsner Urquell—the only place on Earth that’s possible. Or how about London? The stately, wisteria-draped Griffin Brewery, home to Fuller’s, is just next to the Thames and contains a living museum of Victorian brewing relics. Fuller’s sometimes offers special deals, like a tour that ends with an eight-year-old bottle of Vintage Ale from the brewery’s private cellars.

There’s no better way to get a rich sense of a brewery than by visiting it. Breweries regularly have special beers available that you can’t easily find anywhere else. And if you’re a little pushy, you can sometimes arrange to speak with a brewer, get a more specialized tour, or even get the brewery to pour out a splash of ripening beer from one of the conditioning tanks. If you have a deep interest in a brewery’s beer, let them know—they are often happy to try to welcome passionate customers. Call or email ahead and see how they might accommodate you.

But even if you just want a more casual experience, plan ahead and take a public tour. If you’ve never been inside a brewery, you’ll find it fascinating and revealing. If you have been inside a brewery—or even fifty—you’ll probably be surprised, too. I have been in scores of breweries across Europe and the U.S., and every time I’ve walked into an unfamiliar one I’ve found something unexpected. To get you started, here’s a tour of some of the classics from around the world. (But don’t be afraid to explore online and chart your own course.) ■

FROM THE CENTRAL city of Brussels, you’re no more than two hours in any direction from the country’s 130 breweries. That opens up a wide vista for travel planning. You have to make a decision whether you wish to go deeply into a particular type of brewing or would rather sample here and there from Belgium’s great buffet. Lambic brewing happens in the Brussels area, and sourheads often make it a point to do a circuit of the area’s breweries and blenderies, such as Boon, Cantillon, De Cam, Drie Fonteinen, Girardin, Hanssens, Lindemans, Mort Subite, or Oud Beersel. Others like to make the rounds of the Trappist breweries. An additional question you want to ask is how well beer tourism fits in with general tourism. Belgium’s sights, including Bruges and Ghent, are pretty spectacular. You don’t want to miss the forest for the trees. (And anyway, no matter where you go, you’ll find a brewery or two.)

A glimpse at the historic cellars beneath Pilsner Urquell

Consider these a starting point of excellent experiences and go from there. If you start in Brussels, Cantillon is a great debut (cantillon.be). You can schedule a guided tour in advance or drop in during open hours—which are expansive. The brewery is a funky little space that looks like an auto shop from the outside—and a bit like that on the inside, too—so put on your game face. Be sure to stop into one of the two Moeder Lambic pubs for a chance to try many more beers from lambic land. If you have time, Drie Fonteinen and Oud Beersel are just south of Brussels in the village of Beerseland and are easy to visit (3fonteinen.be; oudbeersel.com).

South of Brussels, in the tiny town of Le Rœulx, is one of the most picturesque breweries in the world—rustic St. Feuillien (st-feuillien.com). Although there’s a bigger production brewery elsewhere, you’ll tour the old tower that served the Friart family, proprietors for over a century.

BELGIAN BREWERIES TO SEE

Much of the best action is west of Brussels in Flanders. One of the top five most awesome brewery experiences is standing next to towering oaken foeders in the thirty-odd cellars of Rodenbach (rodenbach.be). The entire brewery is gorgeous, and goes from state-of-the-art modern to nineteenth-century traditional.

One of the reasons some people visit Belgium is to secure a bottle from the most reclusive monks of Sint Sixtus at Westvleteren (sintsixtus.be)—and the only place to do it is the abbey in the town of the same name. Stop in at In de Vrede, the little café (indevrede.be), and have a thick slab of cheese with a goblet of beer. You can’t visit the brewery, but you can walk around the grounds a bit and down the lovely Wandelpad to an outdoor shrine (sintsixtus.be).

Finally, De Dolle Brouwers offers a tour of their brewery every Sunday afternoon. Even though the company is relatively young, you’ll find wonderfully funky old equipment gathered up by the “Mad Brewers”—and enjoy a great beer afterward (dedollebrouwers.be).

Beer is so closely woven into the fabric of Belgian culture that there’s no bad time to visit. Rather, set your itinerary based on what you wish to see. To see a lambic brewery in action, you have to go between November and March. Summer, however, allows you to bike around the tiny village roads and through fields of sprouts and hops (in Flanders, anyway). But don’t forget September, when Belgian Beer Weekend turns Brussels’s Grand Place into a spectacle of brewing ritual and history. ■

WITH GERMANY you don’t have the luxury of proximity. The country is large and diverse, and unfortunately—or fortunately, depending on your perspective—for the beer tourist, there are a lot of excellent places to visit. The two cities of the Rhine, Düsseldorf and Cologne, are absolutely wonderful beer towns. They have beer drinking culture unique in the world (see Ales of the Rhine), and a tour of Uerige, one of Germany’s most traditional breweries, is worth a trip all on its own. But the force of gravity inevitably draws the tourist south, to Franconia and Bavaria, the seat of lager brewing and the heart of the German tradition. The majority of the country’s breweries are located there, as well as many of the most famous. If you go to Germany looking for beer, you go to Bavaria.

If you go one place in Germany for beer, make it Franconia and the city at its heart, Bamberg. Bamberg is itself an incredible jewel, a wholly intact town with stunning half-timbered medieval architecture and history everywhere you look. In fact, UNESCO declared the entire old town a World Heritage site in 1993. It also has nine local breweries—impressive for a town of 70,000 people—including Mahr’s, Schlenkerla, Ambräusianum, and Spezial, where the breweries make the local specialties of rauchbier and ungespundet. The Bamberg breweries don’t offer tours, but the pubs are the real show, anyway. You could easily spend a week and never leave Bamberg’s old city, but if you want to go on road trips, Brauerei Hartmann in neighboring Würgau is a good bet, and they do tours, as well (brauerei-hartmann.de). South of Bamberg in Hallendorf is Brauerei Rittmayer (rittmayer.de), another excellent outing. If you’re looking to go farther afield, take a jaunt to Bayreuth, home to Aktien, Becher Bräu, Maisel (which has a museum), and Schinner (aktienbrauerei.de; becherbraeu.de; maisel.com; buergerbraeu-schinner.de).

Only barely behind Bamberg in terms of interest is the grand brewing city of Munich. It’s impossible to overstate Munich’s importance in brewing, and best of all for the visitor, much of the tradition lives on in an unbroken lineage. The famous old breweries like Paulaner, Spaten, Hacker-Pschorr, Augustiner, and the Hofbräuhaus are still brewing their famous lagers and weisses. Most offer tours, so check websites for information (paulaner.com; spatenbeer.com; hacker-pschorr.com; augustiner-braeu.de; hofbraeu-muenchen.de).

Just outside Munich are two other important destinations. Near the airport north of town is Weihenstephan in Freising (weihenstephaner.de). Brewing has been conducted continuously on this site longer than any other in the world, and the state-owned brewery doubles as a university and anchors the most important brewing programs in the world. If you take a tour there, one of the students will act as your guide. It is situated on a leafy campus and there’s a cozy little pub near the brewery.

Another must-see is the monastic brewery Andechs (andechs.de), just southwest of Munich. It’s a gorgeous abbey, with a classic Bavarian onion-dome spire and steep-roofed buildings, situated on a hill next to Lake Ammer—an easy day trip from the city. You can spend time seeing the abbey, touring the brewery, and of course, spending a few euros in the enormous beer garden afterward.

With something going on most of the year, the only real downtime in Germany is the period between the New Year and spring (but even then, snuggling up in a warm pub with sausages and a dark lager has its allure). Munich’s Oktoberfest is staged the last two weeks in September and the first week of October. Bock tappings happen across Franconia from September through December. And then there’s summer, which as we all know was the season invented to enable sipping helles bier in beer gardens. ■

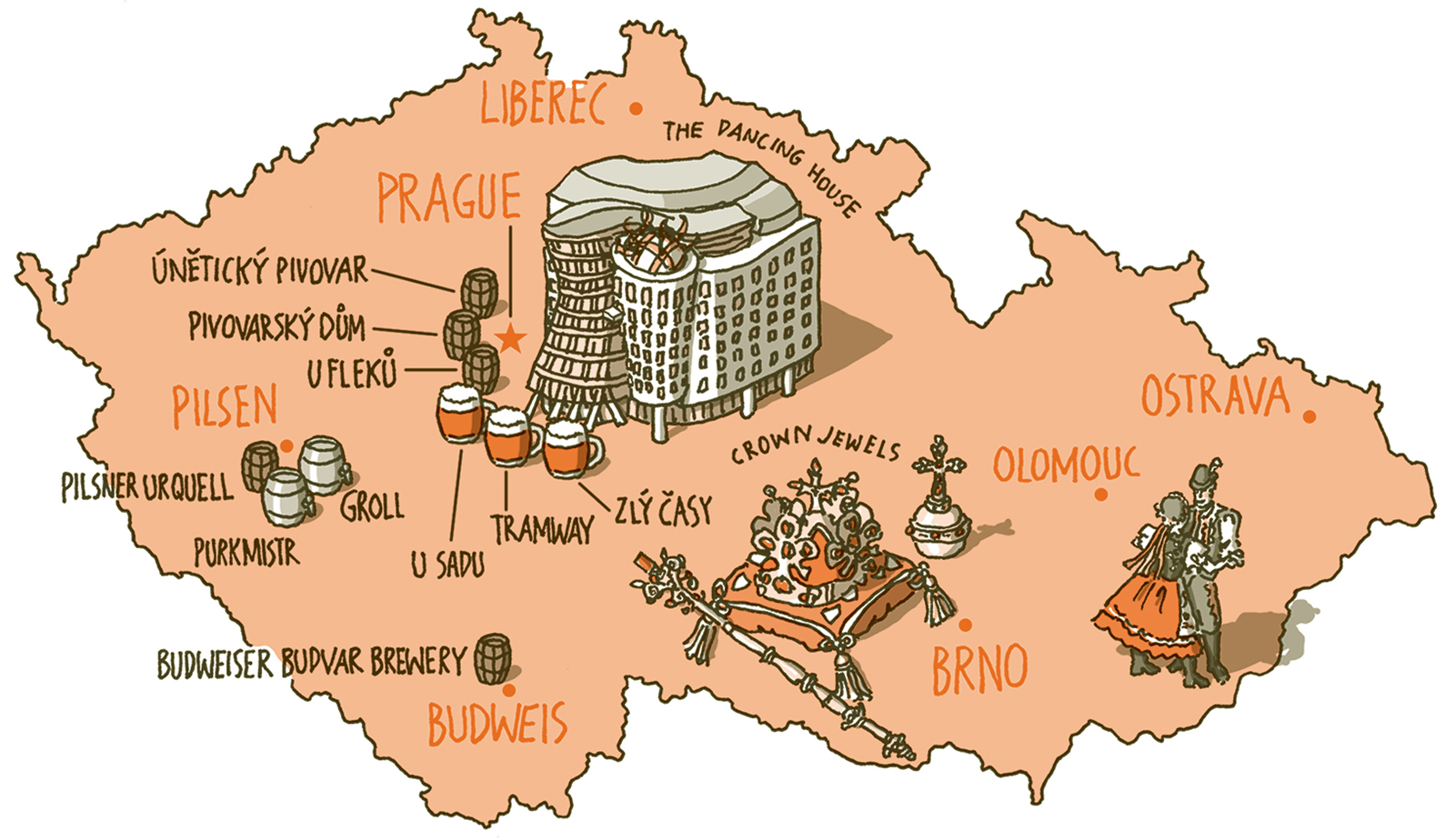

FAR TOO FEW beer tourists put the Czech Republic on their wish list—and they cheat themselves by ignoring this amazing brewing oasis. The remarkable thing is: It’s getting better. Craft brewing fever hit the Czech Republic in the past several years, and now it’s as easy to find a good pint in Prague as in Pilsen. In fact, for the first time in decades, Prague has become a vital piece of the country’s brewing scene. Bohemia, the Czech Republic’s western half, is only about twice as big as tiny Belgium (one-seventh the size of Germany), which makes it a manageable destination.

CZECH BREWERIES TO SEE

It is still very much worth traveling to Pilsen to see Pilsner Urquell (prazdrojvisit.cz). There’s something momentous about walking through the huge anniversary gate and into the brewery that changed the face of brewing across the world. It’s a great tour, offered in Czech, English, or German, and finishes with that famous tipple of wood-aged pilsner. Pilsen also has a nice brewing museum near the cathedral, and two small brewpubs, Purkmistr and Groll (purkmistr.cz; pivovargroll.cz), have had the temerity to open up in the shadow of Urquell. Pilsen is just sixty miles west of Prague, an easy train ride. Ninety miles south of the capital, in Budweis (České Budějovice) is the other famous national brewery, Budvar (budejovickybudvar.cz). Tours run Monday through Friday in multiple languages from April through November.

Prague is one of the great cities of the world, at times the seat of emperors and kings, and budget-minded travelers have enjoyed seeing the city of spires for prices half that of lesser cities in Western Europe. While Prague isn’t home to a surfeit of ancient, famous breweries to match Pilsen and Budweis, it is now a beery destination in its own right. What changed everything was the rise of independent pubs with multiple taps from a variety of breweries (called čtvrtá pípa or “fourth tap”). Much as is happening elsewhere, these places offer a wide selection of beers, including ales. They’re actually the places to go to find a wide selection of the country’s beer. Try Zlý Časy (zlycasy.eu), which has the look of a neighborhood pub but perhaps the largest taplist in the city; Tramway, where you can sit in an actual old tram and where the concept of fourth tap was born (prvnipivnitramway.cz); and U Sadu (usadu.cz), with a riot of weird objects on the walls, some local ales, and even vegetarian food—and an English-language menu!

Prague also has some good breweries to consider. In town, U Fleků (ufleku.cz) is an institution, dating back hundreds of years, and you’ll want to try their dark lager. For a contrast, try one of the newest breweries in town, Únětický Pivovar (unetickypivovar.cz). It’s actually located about seven miles north of Prague Castle, and getting there via public transportation can be a bit of a challenge. Persevere. The brewery only makes two beers, both pale lagers, and they were the best I had in the Czech Republic. Ask around and they might show you their tiny brewery. Finally, Pivovarský Dům (pivovarskydum.com) is a good stop; it illustrates how the country is changing. Owned by a company that recently started a new brewery in an old monastery, they make the usual lineup of lagers but have recently introduced strange potions like sour cherry and nettle beers.

There’s no bad time to visit the Czech Republic. If you’re hardy, the winter can be enchanting under a blanket of snow. And nothing warms quite so well as a cozy pub. ■

THE ISLAND OF Great Britain is about the size of Minnesota, and yet it feels much bigger. Even the spans of northern and southern England seem vast. This means that getting around feels more arduous than it is (not so great), but also that different regions reward travelers with a whole different slate of local beers (great). Breweries in England and Scotland are pretty good about offering tours, but you have to schedule ahead. It’s mandatory to see some of the old breweries, which stand as a record of decades past and will help you understand why cask ale remains a national trust. But it’s also mandatory to spend a goodly time in pubs as well—that’s where British beer culture thrives. What follows is a smattering of wonderful old breweries to visit; they are spread out across the country. I recommend, however, that you select a location and really get to know it rather than traipsing across the island without delving deeply into any one place.

The following breweries are arranged in such a way that if you were to ignore my advice and do a grand tour, this would do nicely. If you do take my advice and camp out in one place, poke around the Internet and see what famous breweries are nearby—this list is only a starting point. Note that the price of most of the tours includes a pint at its conclusion.

A few of the old breweries have retained nineteenth-century traditions like employing coopers and delivering beer by dray horse. One is Wadworth (wadworthvisitorcentre.co.uk), a brewery in Wiltshire, in southwest England. The tour takes you to both the cooperage and stables. Hook Norton (hooky.co.uk) is located in nearby Oxfordshire, and is possibly the signature Victorian tower brewery—at least among those open for touring. Not only does it have many of the old fixtures found elsewhere, but Hook Norton also maintains the last of the country’s steam engines.

London is eighty miles southeast of Hook Norton, and there you’ll find Fuller’s (www.fullers.co.uk). Fuller’s also runs some of the most handsome pubs around, and you find them scattered across the city—don’t hesitate to pop in for a pint. London’s also a wonderful place to drink, and one of the best places to find newer craft beers. The Rake, at Borough Market (utobeer.co.uk/the-rake) and Craft Beer Company in Clerkenwell and other neighborhoods (thecraftbeerco.com/pubs) are two of the best known. If you’ve read Pete Brown’s book Shakespeare’s Local, you can also look for the venerable pub in Southwark. While in London, you might be interested in newer breweries as well, and both The Kernel, at the Spa Terminus in Bermondsey (thekernelbrewery.com), and Meantime, in Greenwich (meantimebrewing.com), are worth seeking out.

To the southeast, in hop country, you’ll find Shepherd Neame (shepherd neame.co.uk), Britain’s oldest brewery. Heading north you come to the picturesque little town of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk and England’s largest ale brewery, Greene King (greenekingshop.co.uk).

Farther north, in the West Midlands, you’ll find Marston’s (marstons.co.uk), one of the remnants of the great brewing tradition of Burton upon Trent. Visiting offers an opportunity to see the last of the old wood-barrel–based Burton Union fermenting systems in action. And while in Burton, be sure to check out the National Brewery Centre museum.

The north of the country awaits, and if I had to visit only one location, I might make it Yorkshire. The ancient city of York is worth the entire trip to England—you can visit the Trembling Madness pub (tremblingmadness.co.uk), with its bizarre collection of hunted heads, including the family rodentia, on the wall—but stray north a bit more until you come to Masham. There you’ll find 200-year-old Theakston (theakstons.co.uk), maker of Old Peculier, employer of a cooper, and brewer of traditional ales. Almost across the street is another brewery owned by a rogue Theakston family member—hence the name Black Sheep Brewery (blacksheepbrewery.com). When he founded the brewery in 1987, Paul Theakston found old equipment, right down to proper Yorkshire squares, and assembled the equipment in an old malthouse to make what looks like—but isn’t—an old brewery.

People visiting Scotland normally look for a different kind of malt. Should you wish to leaven your whisky tour with a brewery visit, I recommend Caledonian (caledonianbeer.com), which is right in Edinburgh and has a wonderfully odd and funky brewhouse, where bell-shaped copper kettles are fed by long copper pipes around which brewers must duck and dodge. Belhaven (belhaven.co.uk) is in nearby Dunbar if one traditional Scottish brewery fails to slake your thirst.

If you really want to immerse yourself in British beer, the Great British Beer Festival, in August, is a grand way to do it. Summer in general is nice—whether you’re biking the rolling hills and picturesque villages of the Cotswolds (good for building a thirst) or strolling through the moors of the Peak District. Mild ale fans might like May, when there’s a month-long celebration. ■

EXCEPT FOR A handful of exceptions, the United States does not offer up sumptuous old breweries as eye candy. The vast, vast majority of our breweries are modern, utilitarian, and appear industrially unremarkable. The reason people bother to travel is for the beer, not the breweries. Much as has happened in other large(ish) beer countries like Germany and the United Kingdom, America has begun to develop beer regions. Most breweries don’t ship their beers farther than a state or three away, and so even very famous beers like those made by New Glarus, Russian River, and Shipyard are not available too far from their home bases. Improvisation and experimentation is America’s niche in the world of beer, and visiting far-flung cities becomes an Easter egg hunt to find the latest release or newest nanobrewery.

As I write this, there are roughly 3,000 breweries in the United States—twice as many as there were a decade earlier. There are breweries in every state, and most citizens live no more than a few miles from one. If you have a local brewery and haven’t checked under the hood, ask around—most are happy to show you how things work. When you travel, you might do the same, especially with smaller breweries. But the main event happens in the glass. Wherever possible, drink small glasses so you can maximize your sampling.

If you want to get a taste of the breadth of American brewing, there are several cities to explore. On the East Coast, Portland, Maine, will give you a good sense of the impressive New England scene. Geary’s (gearybrewing.com) and Allagash (allagash.com) are two of the nation’s finest, and samples of Shipyard (shipyard.com) and Gritty McDuff’s (grittys.com) will clue you in to the (old) English roots of this scene. The Newcomer Maine Brewing (mainebeer company.com) may show its future.

The other great East Coast city—and one with a credible claim to be the nation’s best—is Philadelphia. This is one of America’s oldest beer towns, in one of the only states to survive Prohibition with a few breweries, and it’s now a craft beer leader. There are some venerable pioneers in and around the city—Dock Street (dockstreetbeer.com), Yards (yardsbrewing.com), Flying Fish (flyingfish.com), Victory (victorybeer.com), and Sly Fox (slyfoxbeer.com)—along with a new crop that includes Philadelphia Brewing (philadelphiabrewing.com) and Earth Bread + Brewery (earthbreadbrewery.com). Add good-food pubs like Monk’s Cafe (monkscafe.com) and you’ve got a lot on your plate.

The middle of the country doesn’t yet have must-see cities like the coasts, but Chicago is coming along. The old guard consists largely of Goose Island (gooseisland.com), which held down the fort for years until reinforcements could arrive. And arrive they have—nearly twenty at last count. Where Chicago really exceeds is food, starting with nationally renowned Publican (thepublicanrestaurant.com). Add gastropubs like Hopleaf (hopleaf.com), The Bristol (thebristolchicago.com), and Longman and Eagle (longmanandeagle.com), and Chicago stands as the city most interested in placing good beer and good food on the same table.

Denver is also in the country’s middle, but as far as brewing is concerned it arrived a long time ago. Home of the Brewers Association and Great American Beer Festival (GABF), Denver’s the kind of town that loves beer so much it would elect a brewer as mayor. (They did—John Hickenlooper—and then elected him governor.) Some of the classics are here, including Great Divide (greatdivide.com) and Wynkoop (the governor’s place; wynkoop.com), and just down the road in Boulder are Avery (averybrewing.com) and Boulder Beer (boulderbeer.com).

The West Coast is lousy with beer cities, including Seattle (20+ breweries), Portland, Oregon (50+), San Francisco (20+), and San Diego (40+, depending on how generous you are with city boundaries). Each has claimed—with justification—to be the nation’s best beer city, and they all have something in common. San Francisco is probably the foodiest, Portland the funkiest, San Diego the hoppiest, and Seattle, well, the rainiest. A visit to any of these cities will leave you wishing you had more time, no matter how long you stay.

American cities, following Philadelphia’s lead, have taken to hosting “beer weeks” to showcase their local breweries. Those are excellent times to visit: San Francisco in February, Chicago and Seattle in May, Philly in June, and San Diego in November. Denver’s beer week is really the nation’s beer week—when the GABF comes to town in October. The best time to visit Portland, Oregon, and Seattle is during the harvest, when the fresh-hop beers are in season—from late September through October. ■

WHAT’S BETTER than a sprawling tavern full of beer drinkers? How about a sunny, picnic table–strewn park full of them? The idea is not a new one. Munich has hosted a fairly well-known October festival for more than 200 years—you may have heard of it. But these so-called Oktoberfests have evolved. When people started to get interested in new-fangled offbeat beers back in the 1980s, breweries realized that festivals created a great way for people to sample their beer. The most famous example is the Great American Beer Festival, an event that helped legitimize the new “microbreweries” that were cropping up then, but the Oregon Brewers Festival and Great Taste of the Midwest have become summer fixtures in Portland and in Madison, Wisconsin.

These American beer events take a slightly different approach from the Oktoberfest model; their focus is more on sampling and tasting a broad spectrum of beers, rather than downing liters of the same festbier. As the decades have passed, the fests have grown more and more specialized. There are fests for cask ales, for winter beers, for imports, even for things as esoteric as fruit beer and beers made with freshly picked hops. Cities host rolling ongoing week-long parties, and many countries have national showcase festivals like Wellington, New Zealand’s Beervana Festival; the Great Japan Beer Fest; Belgian Beer Weekend; and on and on. Michigan-based beer writer Paul Ruschmann maintains a website with listings for fests around the world, beerfestivals.org, and he was tracking more than 1,300 at last count. If you can imagine a type of festival, someone’s probably already hosting one.

The Great American Beer Festival as viewed through a glass

Festivals aren’t just a way to get a lot of beer into your belly. Well-curated fests are enormously interesting. In an afternoon’s time, a drinker can try a dozen samples of beer. The first witbier I ever tried was at the Oregon Brewers Festival in the early 1990s. Belgian ales were at the time an obscure oddity, and I had never heard of witbier. Even the idea—“white” beer—was strange. But on that balmy July afternoon, I thought I had never tasted an ale as good as that wheaty tipple. In subsequent years I tried my first bourbon barrel–aged beer, my first braggot, and my first black IPA at beer festivals. For the beer curious, nothing satisfies like a good festival.

Following is a small selection of festivals, roughly organized by month, to give you a sense of their breadth. For people planning vacations, they make wonderful focal points.

■ SAVOR (Washington, D.C., in May or June). Hosted by the Brewers Association, Savor is the premier fest to highlight pairings of beer and food. Attendees sample beer alongside cuisine prepared to match each pour. There are educational salons and area beer events that take advantage of the unique marriage of food and beer.

■ GREAT TASTE OF THE MIDWEST (Madison, WI, in August) and OREGON BREWERS FESTIVAL (Portland, OR, in July). These are the two grand old regional fests of the United States, founded in 1986 and 1988, respectively. The Great Taste is held in Olin Park, on the edge of Madison’s Lake Monona. The Fest is frustratingly short—just five hours on one Saturday in August—but boasts an insane variety of beers that fans navigate with phone apps or a dense guide running over a hundred pages. The Oregon Brewers Fest runs from Wednesday through Sunday and has a more modest selection of predominantly local beers. Held on the bank of the Willamette River in downtown Portland, it attracts 100,000 visitors a year.

■ GREAT BRITISH BEER FESTIVAL (London in early August). Organized by the Campaign for Real Ale, the venerable British organization devoted to promoting traditional ales, this is the world’s great celebration of cask ale. It includes beers and ciders from around the globe, but there are hundreds of local products on cask—pure heaven for lovers of British ales. This is the fest where judges crown an annual “champion beer of Britain”—the only event in the world where mild ales regularly win. As craft breweries have become ale rivals to old cask-ale breweries, they have introduced their own fest, also held in London in August: the London Craft Beer Festival.

The Oregon Brewers Festival begins with a parade through the streets of Portland.

■ OKTOBERFEST (Munich in September and October). A force of nature. People go to Oktoberfest as much for the throngs in dirndls and lederhosen as the beer—but beer remains at the center of the festivities. Only six breweries can sell their beer there—Augustiner, Hacker-Pschorr, Löwenbrau, Paulaner, Spaten, and the Hofbräuhaus—and they have the exclusive right to call it Oktoberfestbier. Munich is deluged with people—a million of them attend each year—and it’s wise to book up to six months in advance.

■ BELGIAN BEER WEEKEND (Brussels in September). Held in the spectacular Grand Place in Brussels, this fest features four dozen Belgian breweries amid lots of Old World pomp and grandeur, including the strange and wonderful parade of the Knighthood of the Brewers’ Mash Staff—it includes a procession of historic beer trucks and men wearing odd, medieval-looking costumes. Like the Great British Beer Festival, this is a premier assemblage of Belgian breweries, including representatives of all the major Belgian beer styles.

■ GREAT AMERICAN BEER FESTIVAL (Denver, CO, in October). The American corollary to the GBBF features nearly twice as many beers from hundreds of breweries across the United States. It is easily the best single place to go to sample beer from small breweries, all found in the cavernous Colorado Convention Center in downtown Denver. Since most have no distribution beyond their local region, it’s a great way to take a tour of the country’s beers, organized by region. The venue itself is a little grim, but the weekend of the fest becomes a rolling party all across Denver, with scads of events held in the crisp early autumn weather.

■ FRESH-HOP FESTIVALS (Hood River, OR, and Yakima, WA, in October). Made with freshly picked, undried hops, fresh-hop ales are made only once a year. Extremely perishable, they last only a few weeks before their flavors fade. The very best way to sample them is at one of these two festivals, which tend to focus on beers from their home states. Both held outdoors under skies that have in past years turned liquid, they nevertheless attract throngs of hopheads who wait all year for these rare, evanescent beers.

■ THE FESTIVAL (Date and location changes). Hosted by importer Dan Shelton, this new fest, founded in 2012, is looking to become the premier venue for imports. Not only does it feature a wide selection of beer styles from around the world, but the brewers are on hand to talk about their products and methods. Based on the first couple years, it’s doing an excellent job. ■