In much of the world, beer names are good, solid nouns: bock, pilsner, lambic. Britons have a penchant for descriptors, like “mild,” “stout,” or “bitter.” These terms aren’t absolutes, though—they indicate relative qualities. The adjective “bitter” is used to distinguish this style from sweet, light milds. It’s the bitterer of the two. But stripped of context, the name misleads. British bitters are characterized by a definite hop presence, but they have no violence in them. The hops ride atop a gentle biscuit sweetness and add marmalade and spice—but they aren’t harsh or what we would, in other contexts, call “bitter.”

Of all the beer styles, the most harmoniously balanced might be bitters. They exhibit equal parts malt, hop, and yeast character, never favoring one over the other. Balance is one of the key factors in these beers, which are designed to be drunk in sessions of twos and threes. No single element wears out its welcome or tires the tongue. Instead, a drinker may stop to admire—even well into his third pint—the lively flavors that impressed him on his first sip. ■

London Pride is a familiar cask bitter in the U.K. capital.

BITTER ALES WERE delayed until two discoveries made their birth possible: hops and modern kilning techniques. People knew about hops at least by the time of Christ, but they didn’t first think to put them into beer until around the ninth century. Before the discovery of hops, beer was mild and sweet, balanced by herbs and spices. In France, the monks who first recorded their use took a long time to spread that particular gospel. (The intervention of war and plague probably didn’t help move things along.) It wasn’t until the early 1400s that hops finally made it to Britain—but only in the beers of immigrant brewers. It took the English another century to find religion and plant their own hops.

Straw-colored malts were also slow in coming. Before the 1640s, kilning was a crude process that left malt smoky and blackened. With the invention of coke—coal processed to drive off toxic chemicals—maltsters had more control over the kilning process and could produce relatively pale malts. The distant ancestors of bitter—heavier, stronger beers—were made with these malts. By the early decades of the 1700s, the great porter epoch was dawning, relegating other styles to niche status. Pale ales were brewed, but not in great quantities.

Pale beers began to find a larger audience around the time Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837. Several factors contributed to their rise. After decades in which London’s porter breweries dominated the country, breweries in Burton upon Trent were finding success with two varieties of paler ales. Since the eighteenth century, brewers there had shipped a heavy brownish ale called “Burton ale” to the Baltics. In 1822, however, the Russian government placed a ban on imported beer (excluding porter), and the market for Burton ales dried up. With a little fine-tuning, making the beer lighter in color and more attenuative, breweries like Allsopp and Bass refashioned Burtons for the British market. They were still strong like Burtons, but pale—a step closer to what we think of as modern bitter.

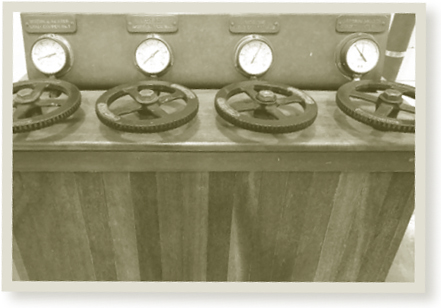

A “Burton Union system” typical of nineteenth-century breweries in the city—this one on view at the National Brewery Centre, Burton upon Trent

The breweries of Burton had a special advantage in producing paler ales: the water. London’s water was highly carbonic; it brought out a harsh note from the hops, a key element in the new pale beers. Burton’s water, which lay in gypsum beds below the city, was rich in calcium sulfate. This brought out hop bitterness without harshness and, as a bonus, worked to clarify the beer. The result was sparklingly vivid ales much of the rest of the country couldn’t match.

Industrialization was one of the main drivers of the period. Porter was still king and would remain so for decades to come, but pales gained popularity as they rode the new rails out of Burton to farther reaches of the kingdom. Another Industrial Age innovation helped raise their profile: machine-made clear glassware. People could see what they were drinking, and the bright-copper pale ales looked mighty nice in a tall, clear glass.

At the middle of the nineteenth century, bitters were not especially strong, but they were made with a great deal of hops. They were also aged, sometimes as long as a year. From at least the middle of the century onward, brewers also made pales with more delicate bitterness; these they called “light bitter.” Although it had been legal to add sugar to grists for twenty years, it wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century that it became more common in bitters.

Bass was once the largest-selling brewery in the world, and its pale ale was the standard bearer for the style.

Although bitters had been brewed for decades, they spent most of their long lives playing second fiddle to other styles. The porter era gave way to milds by the turn of the twentieth century, and milds remained the ascendant tipple through the 1950s. When the world wars did come, rationing ravaged bitters as it did all styles, and their strengths plummeted. It wasn’t until the Beatles were shaking the foundations at Wembley Stadium that bitter would finally become the country’s bestseller. Among ale styles in Britain, it still reigns.

Kent Golding and Fuggle. Hops got to Britain late, centuries after they had been spicing continental ales. Britain’s beers would one day be famous for their hops, but the local brewers were slow to adopt them. The first fields were eventually planted in Kent, a county southeast of London, the region that would later become the hop heartland of the kingdom. Hops were a lucrative cash crop; the harvest was so massive that until World War II, as many as 80,000 Londoners would board trains and spend working vacations in Kent picking the bines in late summer. Growers bred a number of hop varieties over those centuries, but none so define modern British ales as Golding and Fuggle.

Golding emerged in the 1780s and brewers immediately recognized their quality. The classic variety is East Kent Golding, although a number of similar strains have been bred over the years. (Confusingly, Styrian Golding, a common modern variety, was bred from Fuggle stock.) East Kent Golding is complex but mutable. Always smooth, it sometimes tends toward the floral (lavender, lilac) or the citric (lemons), while at other times it can be sweet, with notes of apricot or marmalade. These different flavors emerge in the beer depending on when the hops are added to the boil and what notes they pick up from other hops, the malt, and as a result of fermentation.

Fuggle came ninety years after Golding and, like its precursor, was a quick hit: It would eventually become the staple hops grown in Britain, accounting for more than three-quarters of the harvest by 1950. A perfect dance partner for the light, top-noted Golding, Fuggle adds depth and gravitas with a woody, earthy, and sometimes peppery hopping. Unfortunately, the English Fuggle crop has struggled in recent years with blight and breweries have begun replacing it with modern strains.

Golding and Fuggle, which have been bred into dozens of other strains, are among the most famous and best-regarded hops in the world—deservedly so. Classic beers using them include Brakspear’s Special, St Austell HSD, Young’s Bitter, Wadworths 6X, Adnams Bitter, Brains SA, and Marston’s Pedigree.

The gentle climate of Kent, England, produces some of the world’s most famous hops.

Pale or Bitter? At their fringes, beer styles always fray. When does a porter become a stout? In the case of pale ales and bitters, it’s not clear that there’s any distinction at all—in the center no less than at the fringes. In the beginning, they were clearly not distinct. On bottle labels, where breweries controlled the message, the name was more often “pale ale,” but in the era before pump clips (the signs attached to tap handles) identified beers, punters called the same beers “bitter” when they ordered a round. Same beer, different names.

Now even Britain’s Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA), the great defender of traditional styles, isn’t sure. Bitter, they say, “grew out of Pale Ale but was generally deep bronze to copper in colour due to the use of slightly darker malts such as crystal that give the beer fullness of palate.” Ah, so it’s color that distinguishes them? Not so much. “Today,” they write, “Pale Ale is usually a bottled version of Bitter.”

One difference is that bitters are generally regarded as a range of beers, some as weak as 3.5% ABV, some as strong as 6%. Pale ales, by contrast, tend toward the middle of the range. Where pale ales truly become distinctive as a separate style is in the hands of Americans, but that’s the subject of the next chapter.

If we tend to think of bitter as the signature style of Britain, it’s because it’s been such a prominent part of pub culture over the past fifty years. Bitter was the dominant style from the 1960s through the 1990s (when, much as was the case everywhere, light lagers supplanted them), and is still the foundation of the cask ale movement in Britain. ■

IF YOU HAD TO SUM UP British brewing with a single style, bitter would be it. Londoner Alastair Hook, the founder of Meantime Brewing, managed to reduce it to one sentence: “The only thing that’s given in Britain is hand-pulled cask ale with a bitterness of thirty and an alcohol of four percent.” To translate: The classic bitter ale is a coppery beer of 4% alcohol and 30 units of bitterness, and a version of this beer is available in every corner of Britain at the local pub. This is the foundation for a range in the style that grows increasingly strong and hoppy at the upper ends.

The price list for the typical range of cask ales in an English pub

What all bitters have in common is an easy drinkability and a careful relationship between the malt and hops. Some may be quite bitter, but these never lose sight (or taste or scent) of their malty foundation. Others may be less bitter—but never do these forget that the style is designed to showcase the flavor and aroma of their native hops. Where they principally deviate is in strength.

The nomenclature of bitters is no more settled than their definition. Some have no name at all, some are called “ordinary bitter,” some just “bitter.” Whatever the name, the smaller of the two categories usually rings in at a specific gravity of 1.040 (10° Plato) or lower—usually 3.5 to 4% in final alcohol content. Bitters aren’t golden; instead, they have a burnished cast and often an off-white head. The nose will be redolent of hops, usually light and spicy, and underneath this the milder notes of fruit and caramel. Ordinary bitters are often made with sugar, leaving them thin of body but crisp.

Some breweries offer two bitters, some three. If there’s a middle bitter, it may be referred to by a variety of names, none precise: “best” or “special,” while the strongest of the bunch might bear a name like “extra special,” “strong,” or “premium.” (To add to the confusion, these names are sometimes swapped between the middle and strongest bitters.) Modern bitter is not a potent style, however, and even strong bitters stay south of 6%. Like ordinary bitters, stronger versions have deep, wood-toned colors. Also like ordinary bitters, the sensations of hop and malt are similar—but more intense. Many stronger bitters will be balanced more toward hops, and cask versions are often dry-hopped to produce especially heady noses.

Burton Bridge, making bitters in a city famous for them

If you look closely at their labels, you’ll notice that some of the classic bitters come in two strengths—one for cask and one for bottle or export keg. This is a clue to the proper habitat of a good bitter. No style benefits more from being served on cask; indeed, when many people try bottles of supposedly world-class bitters, they wonder what the fuss is about.

Cask-conditioning presents beer in its most essential, naked state. The flavors and aromas in bitters come with lots of elbow room, unstuffed and unadorned with the exotic or intense sensations found in some of the ales of other countries. They unfold and blossom in a way that further exposes the lovely marriage between their elements. Beer packaged by cask is pulled from the fermenting tanks just before the yeast has finished its work. (This can be one reason why a cask ale is listed at a lower alcohol percentage than its bottled—and fully fermented—counterpart.) Once in the cask (or “firkin”), the yeast will eat up the remaining sugars and naturally carbonate the cask. By tradition, carbonation levels are kept low—about half the amount of a standard American lager. This practice dates back to a time when casks were actually made of wood and could only tolerate low pressure. What comes from the swan neck at the pub is living beer, and it will continue to ripen in the pub cellar.

Moreish. If you visit a pub in Britain, you might encounter the adjective “moreish” (that is, moreish) applied to beer. The term has a straightforward meaning—the quality of being pleasant over the course of a few pints—and yet it says almost as much about the British as it does about their beer. In no place on Earth do people more enjoy pubgoing than in Britain. This dates back to the period before central heating, when a barroom was likely more cozy than a drafty sitting room. People spent not just an hour or two in a pub, but whole evenings. Patrons prized beer they could drink over several hours, one that remained lively and interesting but didn’t lead quickly to drunkenness. Over time, the beers that evolved were low in alcohol but toothsome and balanced; none is more suited for an evening’s session than bitter.

Sadly, the days when life orbited around the local pub now seem to be fading, and over the past decade Britain has seen the closure of thousands of pubs. For the first time in history, the amount of beer consumed on draft has fallen below 50 percent. In those pubs still peopled by real ale fans, however, the quality of moreishness is a necessity, not a luxury.

I had sampled many bitters in my life, but the first time I actually tasted one was when I found Coniston Bluebird Bitter on cask in the U.S. At just 3.6%, it is tiny by American standards, and yet on cask it is a seductive, spicy tour de force. I was left gasping. You don’t find cask bitter too often in North America, but always be on the lookout: Your sleuthing will be rewarded with a revelatory pour. ■

BITTERS ACHIEVE excellence through a kind of Zen simplicity. I have tasted examples made with a single malt and a single hop that nevertheless exhibited enormous depth—anything more would have been an affectation. This is the hallmark of the style. The grist usually has more than one malt but the goal is always an uncomplicated foundation. A typical recipe starts with a broad base of pale malts (90 percent of the grist or more), and may include a touch of crystal malt for flavor and a very small amount of darker malt for color.

The reason the simplicity of grist works depends on the richness of source malts, particularly the famous British pale malt. The names of different barley strains from which they come have a poetry about them—Plumage Archer, Maris Otter, Halcyon, Pearl, and Pipkin—and new varieties are constantly in rotation. Each malt has different qualities and characteristics, and breweries make choices based on the quality they’re looking for—more breadiness or nuttiness, or any number of subtle flavors. Americans tend to think of Maris Otter, one of the most famous malts, which results in richly malty, bready beers, as the flavor of Britain. But for that same reason, other breweries eschew it. They prefer malts with different characteristics. When I visited Samuel Smith’s, head brewer Steve Barrett said, “We’ve not used Maris Otter in the twenty-seven years I’ve been here.” He uses Tipple and a bit of Optic.

One of the many copper English mash tuns dating to the nineteenth century, Greene King, Bury St Edmunds, England

Another important British process that adds even more flavor and character is floor malting. While modern industrial techniques allow maltsters to maximize malt’s potential sugars—the chemical breakdown of starches and proteins into sugars and enzymes—floor malting is the traditional practice, done manually in the cooler months. It results in a highly modified product, a more richly aromatic and flavorful malt—attributes that carry over into otherwise simple beers. They are the soul of a bitter.

British Barley. In the U.S., brewers mainly speak of two- or six-row barley, not specific strains. In Britain, barleys are as important as hops in producing rich flavors in the country’s low-gravity beer and, like hops, come in different, named varieties. New varieties are constantly being developed, and certain barleys come into popularity while others fall out. The churn is, if anything, more vigorous than it is among hop varieties. The king of British barley is Maris Otter, which for many people defines the flavor of England. A cross of two older strains bred in the 1960s, it is low in protein, producing a distinctive biscuit flavor. Maris Otter has had impressive lasting strength among malts, surviving long after others, like Pipkin, fell out of favor. Halcyon, Pearl, and Optic have emerged as alternate strains, and Golden Promise remains a Scottish favorite.

The storage loft of an English malthouse built around 1834 serves as a maltings depository.

It is also common for breweries to add a small amount of brewing sugar to their bitter recipes—not to sweeten the beer, though. Using nineteenth-century equipment and malt, it was much harder to produce consistent beer speedily, and sugar helped the process. Now it’s exceedingly common. Sugar, in contrast to malt, is completely converted to alcohol, which in turn thins the body and creates a crisper beer—key markers of the style. This gives brewers the best of both worlds: The malts can express their flavor and aroma without making the beer heavy or crowding out those all-important hops. Moreover, a crisp finish is ideal in a beer that drinkers will be enjoying pint after pint.

Of course, the focal point of a bitter is the hops—and in this quintessentially British style, that usually means English hops. If terroir has any place in brewing, it’s in the way hops adapt to the soil and environment. Czech varieties are tangy, German strains spicy, American hops wild and citrusy, and the British have fruity, earthy, and peppery types. Many breweries just start with the classic, Golding, then augment them with Fuggle, Target, Challenger, Northdown, Progress, or First Gold. In order to accentuate the fresh, green character of the hops, many brewers tuck a sachet of whole hops into the cask at packaging (a form of dryhopping)—another advantage to cask-conditioning beer. Even Americans tend to hew pretty closely to tradition when making bitters, and if they use local varieties, they choose the ones that were derived from English strains, like Willamette, which is a barely changed Fuggle.

The final element defining bitter ales is the water—or rather, the minerals in the water. The modern style has its origins in the beers of Burton upon Trent, famous for the hard, sulfurous water that bubbles up through its wells. No other brewing city in the world had water with as much dissolved solids as Burton’s, which exercised a strong influence in the development of style. The contribution of those solids—calcium, sulfates, carbonate, magnesium, and sodium—is to create a “stiff” sensation like carbonation on the tongue. They accentuate and draw out hopping. Other cities have less minerally water than Burton, but everywhere I traveled in Britain, from Brighton to York, brewers described the water as hard.

The grain mill in a traditional English brewery

One of the ways to instantly recognize the difference between American and English ales comes from the water. When American brewer David Geary was making his pale ale, the first thing he did was amend the water. “We have what the Scots would call ‘whisky water’ here in Maine—totally devoid of minerals—so we add gypsum” to stiffen it up. If you see a beer described by a U.S. brewery as a “traditional bitter” or find the word “Burton” anywhere in the description, it means the brewer treated the water with extra salts and minerals. ■

AS PALE BEERS began to enter the market as a rival to porters 150 years ago, they hadn’t yet cohered into a style. Some were lightly hopped low-alcohol beers (“ales”) designed to be drunk within a couple weeks of brewing. Others were stronger and more heavily hopped (“beers”). Eventually, the lineages would split and the former would become “milds,” the latter “pales” and “bitters.” Ah, but what of pales and bitter? Two names for the same style, or something separate?

The question is as much a matter of philosophy as taxonomy—is a tomato a fruit or a vegetable? Without taking sides in what has become an ancient battle, it is worth pointing out a few salient distinctions. Of the two, only pale ales migrated beyond Britain. They are brewed broadly and are perhaps the most commercially successful style of ale in the world. Bitters, on the other hand, mainly stayed on the island. Bitter, unlike pale ale, isn’t just a style of beer—it’s a cultural artifact. The proper consumption of bitter (on cask in a pub), the specificity of the hop character, and the slight salty wash—these things are as much a part of place as gumbo is of Louisiana.

As a consequence, they are at best a niche style elsewhere—and usually brewed in homage to the old country. That doesn’t mean there aren’t good examples elsewhere, particularly in the U.S. But since it is a style of tradition, bitter doesn’t lend itself to tinkering. Brewers with a hankering for the taste of England brew them, but they usually stick close to the script. For innovation, they’ve got pales and IPAs instead.

The Role of “Rationalization.” Few industries are as sensitive to economies of scale as brewing. Because of complex regulations, taxes, and ingredient costs, much of the price of a pint of beer goes somewhere other than the brewer’s pocket. If he can shave a few pence off his own costs, he can increase his margins. The result is consolidation—“rationalization” in the United Kingdom. And the rationalizing the British did, beginning in the 1950s, was no less impressive than consolidation that happened under Miller, Coors, and Budweiser in the U.S. In the early 1800s, when brewing was typically not a commercial enterprise in the way we think of it, Britain had 50,000 breweries. It still had more than 1,300 by the turn of the twentieth century. Stunningly, only 141 remained by 1976—and six companies collectively accounted for 75 percent of the beer brewed in the U.K.

As in the U.S., however, this was not the terminal state. The same kind of depressing decline in character and individuality accompanied consolidation and led, perhaps poetically, to an unexpected end. The big six too sold out to even larger concerns like Heineken and Interbrew (which through several mergers has become InBev). Two, Whitbread and Bass, decided to scrap their brewery operations to focus on pubs and hotels—it was no longer rational for their breweries to make beer. Meanwhile, the vacuum created an opportunity for smaller breweries to enter the market, and now the United Kingdom boasts more than 1,000 breweries.

Which is not to say that bitter is wholly static in its home country. A new crop of microbreweries have spruced up the old style and given it a few modern innovations. In Sussex, Dark Star offers a perfectly traditional Best Bitter, but for those who thrill to adventure, they have a fast little number called Hophead that is simultaneously lighter in body than most bitters but far stronger in hop flavor and aroma (and they use American Cascades, to boot). Still, it’s served on cask and comes in at a very British 3.8% ABV.

In Derbyshire, Thornbridge Brewery’s classic bitter, Lord Marples, is named for a noble who once lived in the house that gives the brewery its name. But Thornbridge’s claim to fame is a range of nontraditional beers that are strange, strong, and vividly hopped. A notable example is Kipling, a robust 5.2% bitter made entirely with Nelson Sauvin hops from New Zealand. In London, Meantime has taken the style even further. Owner and brewer Alastair Hook had a long, slow epiphany. A German-trained brewer who spent time watching the American craft brewing industry take hold, he conceived a beer that looked very much like a standard bitter through most of its creation—the best British malts and hops, brewed at session strength. The one difference? He pitched it with lager yeast. Within its first six months of life, London Lager took up a quarter of Meantime’s production.

The historic Marston’s Brewery in Burton upon Trent pioneered the Burton Union system.

Other breweries like Marble, Hardknott, Ilkley, and Moor are making the next generation of bitter. They don’t always use traditional ingredients in their bitters, and some aren’t even served on cask. A new generation of younger drinkers has taken to slightly edgier beers and they don’t insist on tradition—“craft brewed” is to them a marker of quality and innovation. Whether these beers remain a niche or begin to loosen the definition of “classic bitter” is an open question. But change does seem to be afoot. ■

BITTER IS A style designed to be dispensed on cask from a beer engine, so it’s not surprising that bottled examples are uncommon. Consequently, the best place to find bitter is on tap at your local brewpub. Failing that, a few bottled examples are available. Bottles shipped from England will certainly be worse for the wear—and the lighter the beer, the more it will have wandered from the brewer’s original intent. Still, it’s worth sampling imported bitters because while they may not be their freshest, they still exhibit the qualities that define the style.

LOCATION: London, England

MALT: Pale, caramel, chocolate

HOPS: Golding, Target, Challenger, Northdown; Golding, Target (bottle only)

4.1% ABV, 30 IBU (on cask); 4.7% ABV, 35 IBU (in bottle)

London Pride might be called a strong bitter at another brewery, but it’s only Fuller’s middle entry. A silky beer accented toward the caramel malt base, it has a fruity palate with apple. The hops are light and floral and keep the palate engaged over a session. My favorite part is a slight mineral undercurrent—a taste of the city’s famous water.

LOCATION: London, England

MALT: Pale, caramel, chocolate

HOPS: Golding, Target, Challenger, Northdown

5.5% ABV, 35 IBU (on cask); 5.9% ABV, 36 IBU (in bottle)

Fuller’s Extra Special Bitter (ESB) is the big brother to London Pride and another bitter, Chiswick, all come from the same parti-gyled mash (see page 142)—an old technique abandoned by nearly every other brewery—each a bit weaker than the last. And big it is. For those who think of English beer as weak and malty, Fuller’s ESB will be a shock. In terms of intensity, it’s comparable to an American IPA, crackling with potency and hop zest. Yet it’s illustrative of the difference between the American and British traditions: ESB has a wonderfully smooth, nutty malt base; the zesty hops have elements of pepper and marmalade in the palate; and the whole beer is tied together by a structured minerality. As a boon to American drinkers, bottles arrive in better shape and give a truer sense of its character than lighter, more delicate bitters. ESB has been named Champion Beer of Britain three different years and is one of the finest ales brewed in the world.

LOCATION: Coniston, England

MALT: Pale, caramel

HOPS: Challenger; Mt. Hood (bottle)

3.6% ABV (on cask); 4.2% ABV (in bottle)

Many breweries make separate draft-and bottle-strength versions of their beers; Coniston actually has two recipes. The cask version is superior by some measure—though, sadly, firkins rarely reach America. The draft version is a symphony of flavor marked by a balance between the soft warmth of the malt (toast, cookie, and caramel) and the lively, zippy hopping that contains notes of lemongrass and currant. In the bottle, the flavors are much more muted.

LOCATION: Paso Robles, CA

MALT: Two-row pale, pale, Munich, caramel, chocolate

HOPS: Magnum, Styrian Golding, East Kent Golding

5.0% ABV, 32 IBU

One of the best American bitters comes from one of the most interesting breweries: Firestone Walker, which employs a “Firestone union” system of oak fermentation (the brewery’s riff on a Burton Union system). The base beer is classically British, with a toffee malt base and sprightly, earthy hops. A depth of flavor comes from the oak, which lends a toasted vanilla flavor and a woody dryness.

LOCATION: Southwold, England

MALT: Pale

HOPS: Fuggle, Golding

3.7% ABV, 33 IBU (on cask); 4.1% ABV, 33 IBU (in bottle)

Adnams amends its water to a Burton profile, and the effect is obvious—its Bitter has a stiff, mineral structure and a touch of burned match—sulfur—in the nose. Minerality draws out hop character, and this beer has loads of crisp, peppery bitterness. Many bitters are silky, but Adnams’s is lively and bright, with a texture reminiscent of club soda. It is a refreshing, restorative bitter.

LOCATION: Keighley, England

MALT: Golden Promise

HOPS: Styrian Golding, Whitbread Golding, Kent Golding, Fuggle

4.1% ABV, 1.042 SP. GR. (on cask); 4.3% ABV, 1.042 SP. GR. (in bottle)

One of the most decorated beers in the United Kingdom, Landlord is on the strongish side, which gives it a bit of room to flex its muscles. The brewery has long relied on Scottish Golden Promise malts, giving the beer a warmth and breadiness, and the Golding and Fuggle hops give it that classic marmalade spice. The yeast is a famous element of the beer, nurtured in open fermenting vessels, and adds fruit and an excellent crisp finish. A classic.

LOCATION: Edinburgh, Scotland

MALT: Golden Promise pale, Optic pale

HOPS: Fuggle, Super Styrian Golding

3.8% ABV (on cask); 4.4% ABV (in bottle)

Don’t pay attention to the name IPA in the name—this beer is a classic bitter. Given the reputation of Scottish breweries for full, malty ales, Caledonian’s are surprisingly dry; they also share a lemongrass note. Both of these qualities suit Deuchars, a zesty, spritzy bitter that very much leans into its hops. Two varieties of pale malt lend little in color—Deuchars is almost pilsner-light—but do hint at warm bread. It was named Champion Beer of Britain in 2002.

LOCATION: Seattle, WA

MALT: Pale, Munich, caramel, Belgian Special B

HOPS: Chinook, Cascade, Centennial

5.9% ABV, 60 IBU

Looking at the ingredients, it seems impossible that Elysian’s very American take on the style will retain much Englishness, but remarkably, it does. Despite hearty hopping, the sweet honey and toffee malts are center stage. The hopping is American, but does have fruity hints that remind you of the British originals.

THE TOWN OF YORK IN NORTHERN ENGLAND IS NOTABLE FOR BEING ONE OF THE COUNTRY’S MOST HISTORIC. AROUND THE OLD CITY RUNS A WALL ERECTED BY THE ROMAN EMPEROR SEVERUS IN THE EARLY 3RD CENTURY 210 CE. INSIDE THE WALLS, BUILDINGS SAG WITH THE WEIGHT OF CENTURIES. THESE VISIBLE SIGNS OF AGE HAVE AN INTERESTING EFFECT ON RESIDENTS—TIME COMPRESSES SO THAT EVENTS DECADES OR CENTURIES IN THE PAST SEEM ALIVE AND CURRENT. PEOPLE DON’T TOSS ASIDE OLD WAYS LIGHTLY—IF, INDEED, THEY EVEN SEEM LIKE OLD WAYS. SOMETHING AS RECENT AS A NINETEENTH- OR TWENTIETH-CENTURY INNOVATION MAY STILL BE ON ITS FIRST LEGS.

One example of the phenomenon can be found twelve miles away in another ancient town called Tadcaster. Built of pale limestone and also founded by the Romans, it’s a brewery town—that limestone makes the water as mineral-rich as Burton upon Trent’s. At one end of High Street, the immense John Smith Brewery greets people coming from either direction; but while John Smith may own a larger market share, it’s a different spur of the Smith line, Samuel Smith, where the true family lineage resides.

The Smith family is intensely private, and they don’t regularly give tours of the brewery, which is largely hidden behind a small, pleasant storefront. Nevertheless, everyone in Tadcaster understands the brewery’s dedication to tradition. In the early morning, they hear the clomp-clomp of the horse-drawn dray as it wheels out onto the streets, burdened with oak casks. From the street, they can see a thin trickle of black smoke from the stack, and if they stop into the brewery pub, they smell the coal fire crackling in the back of the room.

This is only the camel’s nose peeking from underneath the tent. Back behind High Street, the old brewery is almost an entirely intact Victorian structure, and the methods used by Sam Smith’s have for the most part remained unchanged for over a century. The original footprint dates to 1758, when the brewery was founded, but the current building was erected in the 1840s.

All breweries were once built at a water source, and Smith sits on two well heads. The water is heavy with calcium sulfate and calcium chloride and is very hard—somewhat less hard than Burton water, but “not dissimilar,” according to head brewer Steve Barrett. Many older breweries still use well water, but most use a process of reverse osmosis to strip out the minerals. Not Smith; when making bitter, they use the water the way they find it (they do amend it for some recipes, however, most notably their lagers).

Near the wells is the boiler room, and near that is a storage room piled high with coal. Old breweries all used coal at one time and many Victorian English breweries still have their old coal chimneys. They give the buildings a romantic grandeur, but none vent smoke anymore. Again, not Smith; the brewery is still fired by coal—“actually quite an economic fuel supply,” says Barrett—same as it has always been.

A state-of-the-art brewery in the mid-nineteenth century was built as a tower to harness the force of gravity, and that’s the way Smith’s still works. Malt is milled on the upper level, and it joins water in the mash tun a level down. The brew kettle is a level lower, and beneath that sit the chillers and fermenters. There’s no elevator, so brewers hike up and down the steep Victorian stairs as they monitor each stage of the brew.

The most famous part of the brewery is near the bottom: the Yorkshire squares. It is still common for older English breweries to use square fermenters; the wide shape means the weight of the beer exerts no pressure on the yeasts, and the corners and edges stifle convection. In a square fermenter, yeasts produce more esters and give English beer the fruity character it’s famous for. In the Smith brewery, the squares are made of Welsh slate, an enormously durable surface that has now outlasted the old steel beams that support them. The brewery is in a slow process of upgrading the supports to stainless—but has no plans to update the slate.

Like much in the brewery, the squares were devised as an ingenious way to solve a nineteenth-century problem. In the early hours of fermentation, yeast rises to a billowy cloud. If the brewery has a way to harvest that yeast, it can re-pitch it in subsequent batches. The Yorkshire squares were designed to maximize harvest. They are actually dual-chambered squares, stacked vertically and joined by a hole in the middle. The bottom chamber is filled nearly to the hole with wort; when the fluffy yeast rises, it spills out through the opening into the upper chamber where it is easily collected. The brewery now uses a vacuum to collect yeast from the top chamber, but this is the only concession to modernity.

The final stage is packaging, and here again, Smith sticks with tradition. Decades ago, breweries put their beer in wooden casks to send out to pubs. Everywhere else in England, stainless-steel kegs replaced wood: Steel is lighter, easier to clean, and requires no tending by a cooper. Not Sam Smith. Their Old Brewery Bitter only goes in wood and is distributed to all their pubs that way. Smith’s is the last brewery to have a full-time cooper on staff, and he not only makes new casks, but tends to the old ones. The barrels do have the virtue of longevity. “We see on some of our labels that some of the staves date back a hundred years,” Barrett told me.

A brew kettle—known as a copper in England

Steam valves are used to regulate the temperature of the kettle.

There is an interesting paradox to the whole enterprise in Tadcaster. The brewery is among the most forward thinking in terms of product development. Its reintroduction of stouts and porters was a major inspiration for American breweries, and foreshadowed the slow return of dark ales to England; its line also includes some of the first organic beers brewed in Britain. Moreover, the brewery has embraced certain technological advancements—key among them, the addition of a laboratory.

In fact, this lab is one of the main reasons the brewery can keep making beer the way it does. At one point during my tour of the brewery, we came across an old Baudelot wort chiller—another antiquated piece of technology. It works by dribbling hot wort from a trough over a vertical stack of coils running with cold water. The brewery only uses this for its India Ale, and does so for the sake of authenticity, not because it has any particular advantages. In fact, “it’s a microbiological nightmare,” Barrett concedes. (Exposing chilled wort to the air could easily introduce unwanted wild yeasts.)

But it’s not a nightmare, really. Barrett told me something that he would repeat when I asked him about the wooden casks—another potential wild-yeast vector. “The lab are always monitoring the microbiology.” Compared to modern equipment, brewing on Smith’s is a high-wire act, but they do have a net.

If anything shows up in the lab, they can make adjustments. The truth is, modern monitoring techniques and a greater awareness of microbiology are the very things that allow Smith to continue to make beer the way they want to, which is to say, the way they always have. ■