She opens her arms to the poor and extends her hands to the needy.

—PROVERBS 31:20

TO DO THIS MONTH:

□ Switch to fair trade products, especially with coffee and chocolate (Isaiah 58:9–12, Malachi 3:5, James 5:4–5)

□ Start recycling (Genesis 2:15)

□ Read Half the Sky by Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, and become a better advocate for the equality and empowerment of women worldwide (Zechariah 7:9–10; James 1:27)

□ Travel to Bolivia with World Vision (Proverbs 31:20; James 1:27)

There is an old Jewish folktale about a man who went out into the world in search of true justice. Somewhere, he believed, a just society must exist, and he would not stop until he found it. His quest lasted many years and took him to many faraway places. He traveled from city to city, village to village, countryside to countryside, seeking justice like a lost treasure, until he had reached the end of the known world.

There, at the edge of the known world, lay a vast, mysterious forest. Determined to continue his quest until justice was found, the man bravely crossed over into the shadows. He searched in the caves of thieves and the huts of witches, where the gruesome inhabitants laughed and scorned him, saying, “Do you really expect to find justice here?”

Undeterred, the man wandered deeper and deeper into the woods, until at last he came upon a small cottage. Through the windows, he spied the warm glow of candles.

Perhaps I will find justice here, he thought to himself.

He knocked at the door, but no one answered. He knocked again, but all was silent. Curious, he pushed open the door and stepped inside.

The moment he entered the cottage, the man realized that it was enchanted, for it expanded in size to become much bigger on the inside than it appeared on the outside. His eyes widened as he realized the cavernous expanse was filled with hundreds of shelves, holding thousands upon thousands of oil candles. Some of the candles sat in fine holders of marble and gold, while others sat in holders of clay or tin. Some were filled with oil so that the flames burned as brightly as the stars, while others had little oil left, and were beginning to grow dim.

The man felt a hand on his shoulder.

He turned to find an old man with a long, white beard, wearing a white robe, standing beside him.

“Shalom aleikhem, my son,” the old man said. “Peace be upon you.”

“Aleikhem shalom,” the startled traveler responded.

“How can I help you?” the old man asked.

“I have traveled the world searching for justice,” he said, “but never have I encountered a place like this. Tell me, what are all these candles for?”

The old man replied, “Each of these candles is a person’s soul. As long as a person’s candle burns, he or she remains alive. But when a person’s candle burns out, the soul is taken away to leave this world.”

“Can you show me the candle of my soul?” the man asked.

“Follow me,” the old man replied, leading his guest through a labyrinth of rooms and shelves, passing row after row of candles.

After what seemed like a long time, they reached a small shelf that held a candle in a holder of clay.

“That is the candle of your soul,” the old man said.

Immediately a wave of fear rushed over the traveler, for the wick of the candle was short and the oil nearly dry. Was his life almost over? Did he have but moments to live?

He then noticed that the candle next to his had a long wick and a tin holder filled with oil. The flame burned brightly, like it could go on forever.

“Whose candle is that?” he asked.

But the old man had disappeared.

The traveler stood there trembling, terrified that his life might be cut short before he found justice. He heard a sputtering sound and saw smoke rising from a higher shelf, signaling the death of someone else somewhere in the world. He looked at his own diminishing candle and then back at the candle next to his, burning so steady and bright. The old man was nowhere to be seen.

So the man picked up the brightly burning candle and lifted it above his own, ready to pour the oil from one holder to another.

Suddenly, he felt a strong grip on his arm.

“Is this the kind of justice you are seeking?” the old man asked.

The traveler closed his eyes in pain and when he opened them, the cottage and the candles and the old man had all vanished. He stood in the dark forest alone. It is said that he could hear the trees whispering his fate.

He had searched for justice in the great wide world but never within himself.

Judaism has no word for “charity.”

Instead the Jews speak of tzedakah, which means “ justice” or “righteousness.”

While the word charity connotes a single act of giving, justice speaks to right living, of aligning oneself with the world in a way that sustains rather than exploits the rest of creation. Justice is not a gift; it’s a lifestyle, a commitment to the Jewish concept of tikkun olam—“repairing the world.”

“What does the Lord require of you?” wrote the prophet Micah. “To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God” (Micah 6:8).

“Is not this the kind of fasting I have chosen,” God asks through Isaiah, “to loose the chains of injustice and untie the cords of the yoke, to set the oppressed free? . . . Is it not to share your food with the hungry, and to provide the poor wanderer with shelter?” (Isaiah 58:6–7).

“Administer true justice,” says Zechariah 7. “Show mercy and compassion to one another. Do not oppress the widow or the fatherless, the alien or the poor” (VV. 9–10).

“Let justice roll down like waters,” declares Amos, “and righteousness like an everflowing stream” (5:24 ESV).

Committed to these central Jewish teachings, Jesus spent the majority of his ministry among the poor, sick, and oppressed, and taught that “whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me ” (Matthew 25:40). The early church followed suit and did such a good job caring for the poor that Julian the Apostate noted with some chagrin that “the godless Galileans [Christians] feed not only their poor but ours also.” According to Luke, “there was not a needy person among them, for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them . . . and distribution was made to each as any had need” (Acts 4:34–35 RSV).

This is why, when Glenn Beck gets on TV and tells Christians to leave churches that advocate social justice, I slap the screen with the backside of my sandal. Justice is one of the most consistent and clear teachings of Scripture, and traditionally, a crucial function of the Church.1 A recent study found that Americans who read their Bibles regularly are 35 percent more likely to say it is important to “actively seek social and economic justice” than those who own a Bible but don’t bother to open it too often.2

So what did all of this mean for my year of biblical womanhood?

I noticed right away that women in Scripture seem particularly concerned with justice. King Lemuel’s mother reminded her son to “speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute. Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy” (Proverbs 31:8–9). The “woman of valor” of Proverbs 31 “opens her arms to the poor and extends her hands to the needy” (V. 20). Hannah praises a God who “raises the poor from the dust and lifts the needy from the ash heap” (1 Samuel 2:8), and in the Magnificat, Mary vows to serve the God who “has lifted up the humble” and “filled the hungry with good things” (Luke 1:52–53). Women like Tabitha are praised in the Bible, while Amos compares women who “oppress the poor and crush the needy” to cows who will be “taken away with hooks” (4:1–2).

I didn’t want to be taken away with meat hooks, or worse yet, compared to a cow, so I dedicated the month of July to practicing justice.

Dan and I already gave to several charities, and we even volunteered from time to time, but these were acts of mercy that had little effect on our day-to-day lives. For the project, I wanted to focus on where the bulk of our money actually went by examining our habits as consumers, particularly what came into the house each week and what left the house each week. This meant taking a hard look at what we ate and what we threw away to see how those habits affected other people and the planet. I also wanted to learn more about the ways women across the world are affected by injustice, so I committed to reading Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn’s highly acclaimed book, Half the Sky, which describes how empowering women can lift entire communities out of poverty and suffering.

This was all I had planned for the month in my initial outline, but things got a lot more interesting when, in June, I got a call from World Vision inviting me to travel with a team of bloggers to Bolivia for a week.

Bolivia. Like, in South America.

The trip was scheduled for the end of July, and the purpose was to give me a firsthand look at how the organization—one of the largest charities in the world—operates on the ground, and to raise funds for World Vision’s child sponsorship program by sharing my experience on the blog.

Opportunities like this one don’t come around that often, especially in years in which you are attempting to obey the Bible literally, so in addition to studying up on ethical consumption and reading Half the Sky, I found myself prepping for my month of justice by getting vaccinated for yellow fever.

“They’re suggesting I get a typhoid shot too,” I told Dan over my cell phone from the health clinic. “It’s not required for the visa; just a precaution.”

“Well, sure, sweetie. Whatever you think.”

“It costs ninety-five bucks.”

Dan was quiet for a few seconds. Then, “You can recover from typhoid, right?”

It was a low point in our personal finance history, but the beginning of my biggest adventure in biblical womanhood yet.

How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses to help?

—1 JOHN 3:17 NRSV

The cool washcloth over my eyes did little to dull the relentless pulses of pain assaulting my sinuses, head, and shoulders. I’d slept for eleven hours straight, and still no relief. When I tried to sit up, it was as though a magnetic pull forced me back down into the damp, twisted sheets. I was too tired to throw up again, too nauseated to move. My limbs felt heavy. The room spun around. So I lay in the fetal position for hours more, listening to the gentle swoosh of the ceiling fan and praying for death.

No, I didn’t get typhoid.

I quit coffee, cold turkey.

There were several reasons for doing so. First, Dan had been pestering me about kicking my caffeine habit for years, and now, with the power invested in him by Commandment #1, he’d become insistent.

“You going to quit caffeine this week?” he kept asking throughout the year.

I managed to put him off for ten months by laughing like he’d just told a good joke, but with Bolivia approaching, I’d been entertaining the notion of quitting anyway. My experience with international travel, particularly in the third world, had taught me that a dependency on two to three cups of coffee each morning can swiftly turn into a liability when you’re staying with a family without a microwave or dishwasher, much less a coffeemaker, or when you’re on a train from Rishikesh to Delhi and everything you’ve ingested so far has resulted in explosive diarrhea. I didn’t want to experience South America in a fog because of a missed cup of coffee . . . even though South America seemed like just about the best place in the world to find one.

More important, my research into consumerism and trade practices had revealed that little to none of the money I shelled out to the big coffee companies each month actually reached the farmers who grew the beans. While demand for coffee has surged over the past twenty years, the price per pound paid to growers has plummeted. Consumers want cheap coffee, and corporations want to keeping posting record profits, and as a result, many of the 25 million farmers who grow coffee for a living are forced to sell their coffee at prices far below the cost of production. Despite long hours in the fields, they struggle to earn a living wage that can support their families.3

The good news is that there are simple ways to ensure that, in the words of activist Deborah James, you “never have to voluntarily put someone in a situation of poverty, exploitation and debt just to enjoy a cup of joe.”4 These days, you can find an array of fair trade coffee products online, at most grocery stores, and even at Starbucks. You just have to look for the black-and-white “fair trade certified” symbol on the package, which ensures that farmers received a guaranteed minimum price for what they produced, that working conditions were safe and ethical, that no child labor was employed, and that workers have a say in the functioning of the farming cooperative.

The bad news, at least for me, is that fair trade coffee is more expensive than what I’d grown accustomed to buying (as it should be, in order for farmers to actually earn a profit), and grocery stores in Dayton aren’t always stocked with the fair trade options. In order to stick to my resolution to only drink fair trade coffee, I had to reduce my dependency, so that my coffee consumption wouldn’t break the bank and so that, in the event that fair trade options weren’t available, I wouldn’t be tempted to settle for my old plastic canister brands. My three-cup addiction was unhealthy enough as it was. I hated the idea of remaining addicted to a product that, when mindlessly consumed, keeps millions of people in poverty. I wanted to get back to the point that coffee was something I enjoyed, not something I needed, so on the morning of July 3, I declared my independence from caffeine and refused to turn on the coffeepot.

The migraine arrived at about three that afternoon.

I went to bed around seven.

The next morning I woke up at eleven, threw up, and immediately crawled back into bed. My state resembled that which theologian C. S. Lewis imagined for the willfully damned: “shrunk and shut up in themselves . . . Their fists are clenched, their teeth are clenched, their eyes fast shut.”5

Dan poked his head in at around four that afternoon to see if I was still alive.

I rose a few hours later to eat, shower, and curse the day I was born.

Then I spent another feverish night curled up in the fetal position, as a bunch of kids down the road set off fireworks like they had some sort of right to do so.

The cycle repeated itself for two more days.

Through it all, I discovered yet another advantage to working from home: you can successfully undergo detox without a whole lot of people noticing. Readers assumed I’d taken a long weekend for the holiday. Friends figured their Fourth of July cookouts included some kind of food that for biblical reasons I couldn’t consume. My family was used to me being distant and crabby. I suffered alone . . . which is exactly how someone who hasn’t washed her hair or put on a bra for three days wants it to be.

Finally, after a week, the headache went away, and I began thinking clearly again, clearly enough to wonder what the heck had convinced my caffeinated self to follow all the Bible’s commandments for women as literally as possible for a year. I found a nice array of fair trade coffee shops online as well as a fair trade, naturally decaffeinated, organic coffee brand at BI-LO that will probably cost my future children their college tuition, but which gives me access to good coffee whenever I get a craving.6 The next task in my month of justice proved a lot less traumatic, even though it involved reexamining a staple product in the Evans household: chocolate.

As it turns out, the majority of the world’s cocoa beans come from West Africa, where farmers sell to major chocolate companies like Hershey’s, Nestlé, and Mars. For the last decade, media reports have detailed horrific working conditions on these cocoa farms, including what can only be described as child slavery. According to the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, there are around 285,000 children working on African cocoa farms. Many of these children have been trafficked from neighboring countries, kidnapped from their families and forced to work without pay on the cocoa farms. The BBC reports that the going rate for a young boy in Mali is around thirty dollars.7 Conditions are hazardous, and child workers are often abused. In fact, the International Labor Rights Fund recently sued the U.S. for failing to enforce laws prohibiting the import of products made with child labor, but the big chocolate companies continue to dodge the numerous deadlines set by Congress to regulate their trade practices.8 A quick survey of the chocolate on our snack shelf revealed that all of it came from chocolate companies associated with child slavery.

I’d love to say I suffered for Jesus on this one, but let me tell you, fair trade chocolate is spectacularly delicious. I asked friends for recommendations, then purchased four chocolate bars from three different fair trade retailers to see which ones Dan and I liked the best. The official taste test, accompanied by a tall glass of milk for Dan and a bottle of rosé for me, began with Green & Black’s Dark 70%, the only fair trade bar I could find in Dayton. I broke off two squares, and together we indulged in one minute of cool, bittersweet chocolate ecstasy. I gave the Green & Black’s a 4.5 out of 5. Dan gave it a 4.

Next we tried the Divine Milk Chocolate bar, which we didn’t like as much, just because we generally preferred dark. Then came the Equal Exchange Organic Dark Chocolate with Almonds, which I officially declared the most wonderful thing I’d ever put in my mouth. I gave it a 5. Dan gave it a 3. We finished with Divine 70% Dark Chocolate with Raspberries, a rich and tart little bite of heaven that we both agreed deserved a 4.

Who knew justice could be so delicious?

While buying and eating fair trade chocolate bars was easy enough, eliminating every trace of big-brand chocolate from our pantry proved a lot more challenging. From the chocolate chunks in our granola bars to baking chips to hot chocolate mix, I found the stuff everywhere, and alternatives were expensive and hard to come by. But knowing what I did about the modern-day slave trade, I couldn’t just shrug it off, not anymore.

The coffee-and-chocolate experiment forced me to confront an uncomfortable fact to which I suspect most Americans can relate: I had absolutely no idea where the majority of my food came from. I didn’t know how much it should actually cost, how it affected the people who harvested and prepared it, or what sort of toll its production took on the planet. I never thought to question the fact that I could purchase a plump red tomato in the middle of January or ask myself why I was willing to regularly ingest a product we call “cheese food.”

So I dedicated the rest of the week, and indeed the rest of the year, to learning more about our habits as consumers. The results were shocking and in some cases disturbing. I’d never realized the degree to which big corporations rely on the mindless habits of consumers to get away with exploitation and neglect. We started to make adjustments here and there, sometimes paying a little extra for items that were fairly traded and, as far as we could tell, ethically produced. It wasn’t easy, and it certainly wasn’t cheap, but it would be one of the most important long-term changes to come out of the project. In a small but daily way we were doing our part to repair the world.

Dan’s Journal

July 15, 2011

This month Rachel has been focusing on charity and justice. This includes learning more about where the things we consume come from and how our actions can affect the lives of those living thousands of miles away. We’ve started recycling, which is a bit of a feat in Dayton since the city doesn’t offer recycling services. The nearest place to recycle glass and plastic is about a half hour away. So far, “recycling” has meant piling pizza boxes, milk cartons, paper, plastic, and glass containers in various places around the kitchen and laundry room with the expectation that, at some point, we’ll try to bring it down to Soddy-Daisy, (yes, that’s the name of the town), where we can recycle them. While living in New Jersey, I got into the habit of recycling, so it was strange to throw everything away when I moved to Dayton. If we could just throw all the recycling into one container and all the trash into the other, life would be a lot easier. But maybe life isn’t supposed to be easy. And how hard is my life, really, when I consider it a bother to sort materials into separate disposal units?

Feminism is the radical notion that women are people.

“It appears that more girls have been killed in the last fifty years, precisely because they were girls, than men were killed in all the wars of the twentieth century,” wrote Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn in Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide. “In the nineteenth century, the central moral challenge was slavery. In the twentieth century, it was the battle against totalitarianism. We believe that in this century the paramount moral challenge will be the struggle for gender equality in the developing world.”9

So begins the book that forever enlarged my view of what it means to fight for women’s equality. In Half the Sky, Kristof and WuDunn, the first married couple to win a Pulitzer Prize in journalism for their international reporting for the New York Times, explore the worldwide scourges of sex trafficking, gender-based violence, and maternal mortality and explain in vivid detail how investing in the health and autonomy of women can lift millions out of poverty.

They share the stories of women like Meena Hasina, a young Indian woman who was kidnapped and sold into sex slavery when she was nine years old. When she escaped and contacted the police, the police only laughed at her, for they were regular customers at the brothel in which she was enslaved. There are at least 3 million women and girls like Meena enslaved in the sex trade.

And the story of Dina, a seventeen-year-old Congolese girl who was gang-raped by five men on her way home from working in the fields. The men shoved a large stick through Dina’s vagina, creating a debilitating fistula—a common ailment among rural African women who have been raped or who suffered through traumatic childbirth without medical attention. Women ages fifteen to forty-four are more likely to be maimed or die from male violence than from cancer, malaria, traffic accidents, and war combined.

And the story of Prudence Lemokouno, a twenty-four-year-old mother of three from Cameroon who went into labor seventy miles from the nearest hospital without any prenatal care. After three days of labor, her untrained birth attendant sat on Prudence’s stomach and bounced up and down to try to get the baby out, rupturing Prudence’s uterus. She died a few days later. A woman like Prudence dies in childbirth every minute.

In addition to excruciating stories like these, Kristoff and WuDunn share the stories of women like Sunitha Krishnan, a tiny but spry Hindu woman from Hyderabad, India, who, after being gang-raped as a young woman, devoted her life to fighting sex trafficking. And Catherine Hamlin, a gynecologist who has presided over more than twenty-five thousand fistula surgeries in Ethiopia. And Sakena Yacoobi, who even under the oppressive rule of the Taliban, opened eighty secret schools for girls.

“Women aren’t the problem,” wrote Kristoff and WuDunn, “but the solution. The plight of girls is no more a tragedy than an opportunity.”10

Indeed, UNICEF reports that the ripple effects of empowering women can change the future of a society. It raises economic productivity, reduces infant mortality, contributes to overall improved health and nutrition, and increases the chances of education for the next generation.11 Several studies suggest that when women are given control over the family spending, more of the money gets devoted to education, medical care, and small business endeavors than when men control the purse strings.12 Similarly, when women vote and hold political office, public spending on health increases and child mortality rate declines.13 Many counterterrorist strategists see women’s empowerment as key to quelling violence and oppression in the Middle East, and women entering the workforce in East Asia generated economic booms in Malaysia, Thailand, and China.14

“In general,” say Kristoff and WuDunn, “the best clue to a nation’s growth and development potential is the status and role of women.”15 “Investment in girls’ education,” says Lawrence Summers, former chief economist of the World Bank, “may well be the highest-return investment available in the developing world.”16

Women aren’t the problem. They are the solution.

The impact of the words reverberated through my thoughts and dreams for months, generating a strange mix of anger and hope that calcified into resolve. These are my sisters who are being abused, silenced, neglected, raped, and sold as slaves. These are my sisters who struggle each day to survive. These are my sisters who, if given the chance, can change the world.

Catholic activist Dorothy Day once said that the “greatest challenge of the day is how to bring about a revolution of the heart, a revolution which has to start with each one of us.”

I knew somewhere deep in my bones that a revolution was afoot, that the women of this earth were rising up, and that, in some way, great or small, I was going to be a part of it.

“Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are you who hunger now, for you will be satisfied. Blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh.”

(LUKE 6:20–21)

The terrain of Cochabamba, Bolivia, is both beautiful and rugged. In the shadow of its snow-covered mountains lie hundreds of arid, rocky hills, where horses and cows perch as skillfully as mountain goats upon the steep slopes where people too make their homes. The high altitude—around 9,000 feet above sea level—leaves even the most skilled climbers breathless. It takes most children over an hour to walk the winding gravel roads to school, and women who live close enough to a health facility to deliver their babies there face a three-mile walk while in labor. The average income is $450 a year.

It’s tough land to farm, so many men leave their families to migrate to Santa Cruz in hopes of harvesting better crops and sending money home. This leaves women and children vulnerable to poverty, malnutrition, dangerous living, and sexual exploitation. Our Bolivian guide told us of children left behind to fend for themselves while their mothers work in the fields, only to fall prey to sexual abuses by relatives and neighbors. Sometimes the fathers return. Sometimes they never do. Sometimes the money suddenly stops coming.

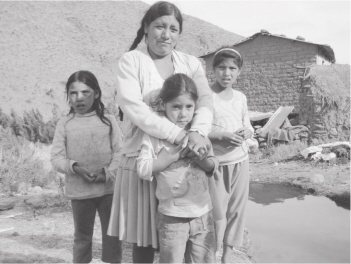

Cinda, a soft-spoken woman with earnest eyes, who like most women in the country wears her long, black hair in two braids down her back, had three little girls and several acres of land to tend when her husband abandoned the family without warning. Although she had the skills she needed to harvest potatoes and beans, her planting time, yield, and variety were severely limited due to a lack of irrigation to her property. It would be difficult for her family to survive with only one adult tending the fields.

Cinda wasn’t the only one facing a water problem. She and her neighbors lived beneath the snow-capped mountain called Hanu. To catch the runoff from melted snow, residents had built a dam, but it was inefficient, providing water for only a few dozen families, and stirring up strife between neighbors desperate for its lifesaving waters. Fortunately, Cinda and her family are part of a World Vision ADP (area development program). Her three girls have sponsors, whose contributions are not only used to purchase school supplies and meals, but are also pooled together with other contributions to help solve community problems.

Partnering with local leaders, World Vision helped the community build and maintain a better dam—a beautiful reservoir of deep blue beneath Hanu, capable of providing irrigation to more than 170 families and stocked with fish for extra protein. The dam and irrigation system were designed by Bolivian engineers, built by local farmers, and are so well maintained by Cinda’s community that they have become self-sustaining, with no additional funding from World Vision necessary.

When I met Cinda, I was heaving from the steep climb through thin air to the mud hut she and her children called home. I’d arrived with three other bloggers, a translator, and Luciano, the World Vision staff member who oversaw the reservoir project. On our way up the hill, we passed a flock of sheep, a couple of llamas, and a very noisy pig—all of whom now belonged to Cinda. Luciano pointed to the small stream flowing through the property and explained it came from the Hanu dam. Three little girls ran out to greet us, a mix of curiosity and shyness on their faces.

“Before the water, I could only grow one kind of potato,” Cinda explained once we’d caught our breath. “Now I have three varieties, and beans too. I sell the extra at the market and use the money to buy sheep.”

The addition of livestock has dramatically improved Cinda’s standard of living. Her daughters are in school. She puts healthy food on the table each day. She can afford basic health care.

Cinda not only cares for her own property but for her mother’s property as well. She is known throughout the area as one of its most successful and generous farmers. Her mother, wrinkled and bent over and browned by the sun, stood behind Cinda and beamed, pride visible in her sunken eyes.

It was all I could do to keep myself from throwing my arms around Cinda and shouting, “Eshet chayil! Woman of valor!”

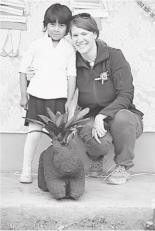

I met so many women of valor in Bolivia that there is not the space to tell their stories. Each morning, our team of eleven—most of us bloggers—would rise early and climb into our fifteen-passenger van to rumble up and down the steep gravel roads that lead to the isolated towns of rural Bolivia. There we would listen mostly, scribbling in our notepads the stories of mothers and fathers, grandparents and children, schoolteachers and aid workers, in hopes that they might inspire our readers to act. We learned about how poor Bolivian women are often forced to work in the potato fields from sunup to sundown, leaving their young children vulnerable to accident and exploitation; how alcoholism and drug abuse plague the teenage population, resulting in school dropouts and domestic abuse; how proper irrigation can turn a deflated community into a thriving one; and how guinea pigs offer more protein than beef and less fat than chicken, making them a highly valuable food source among Bolivia’s malnourished and a worthy income-producing venture for those who farm them.

In a town called Viloma, we met Marta. Now in her forties, Marta was once one of World Vision’s sponsored children. She grew up in a rural area west of Cochabamba, where most girls dropped out of school, married young, and worked in the fields to support their families. As soon as she hit puberty, Marta’s parents tried to convince her to marry a man from Viloma, but Marta loved school and begged to continue. With the help of a teacher, she escaped to the city, where she learned a trade by day and attended school at night.

“I did not oppose getting married and having children,” she told us, “but the women here work in the fields from the moment the sun rises to when it sets. They leave their little ones to play in dangerous places, and are exhausted each night. I wanted something different—for my future children and for myself.”

Marta became such a skilled seamstress that when she married and moved back to Viloma, the area development program sponsored by World Vision employed her. Now Marta manages ten other seamstresses—all mothers of sponsored children—who make blankets, purses, and satchels for World Vision as well as several local clients. The sewing station is located right next to the local school, so Marta can keep an eye on her three children. Mothers of younger children are allowed to care for their toddlers while they work, and their wages far surpass those they would earn by working in the fields.

When we visited the ADP, Marta’s sewing crew had just finished making more than two hundred colorful winter blankets to hand out to every sponsored child in Viloma, enough to fill two rooms, floor to ceiling! As Marta brought us from room to room, I grasped her hand in mine and told her that she reminded me of Tabitha from the Bible, the disciple who made clothing for orphans and widows.

Women aren’t the problem; they are the solution.

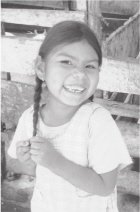

In a dusty neighborhood nearby, we met Elena. Though Elena’s home is located right in the middle of a village outside of Cochabamba, to get there, we had to cross a muddy ravine by walking across a plank. A brood of chickens guarded the other side, clucking nervously at our arrival. We must have been a sight, inching our way across that narrow beam, most of us women with cameras and notepads and giant sunglasses. As soon as we crossed the ravine, we passed through a tall fence made of branches and brush, where we were greeted by the distinct stench of a pig farm, the unmistakable sound of oinks and squeals issuing from two rows of covered pig stalls, and giggles.

A six-year-old girl welcomed us at the gate and led us down the dusty path between the stalls. She served as our official guide through the small, enclosed family farm that, in the space of about fifteen hundred square feet, included more than thirty sows, twenty piglets, several chickens and a rooster, and a brand-new World Vision–sponsored guinea pig module housing dozens of guinea pigs and their babies. When we asked where she lived, she pointed to a heap of blankets and crude kitchen in one corner of the flimsy metal structure that covered the pig stalls.

In spite of the mess around her, the little girl wore a pristine plaid jumper over a light-pink shirt. Her face and hands were clean and her tennis shoes in good shape. No doubt this was the work of her mother, who emerged from the kitchen area to welcome us to her home.

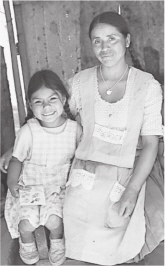

Elena bears all the marks of rural poverty—a weathered face, missing teeth, a curved back—and yet she carries herself with the confidence and ease of a beautiful woman. With full lips, high cheekbones, and kind eyes, Elena is indeed beautiful, and she, too, had worn her best clothes that day, a light-blue top and dusty purple skirt, covered by an embroidered apron. She rested her hands affectionately on the little girl, named Arminda, and told us her story.

Five years before, Elena’s husband had suffered a minor stroke. He waited years before going to a doctor, and Elena had no idea what might be wrong with him. The farm fell into disrepair. Food became scarce. Like a quarter of the Bolivian population, the family began to suffer from malnutrition.

It was in the midst of all of this that Elena took Arminda in. Arminda had been abandoned by her own poverty-stricken family at the age of two, left to live on a street corner, where she ate dirty noodles off the ground. When Elena saw the little girl, her heart was moved with compassion. She took Arminda home with her, inquired after her family, and when Arminda’s mother said she didn’t want the child anymore, filed papers to officially adopt her.

When Arminda and her brothers got World Vision sponsors, the World Vision staff finally convinced Elena’s husband to see a doctor. His condition is improving, and with the addition of the guinea pig farm, the family hopes to earn enough money to build a house, a prospect that fills Elena’s eyes with hopeful tears. It would only cost around fifteen hundred dollars for Elena to have a real home.

When we marveled at her generosity for adopting Arminda despite her own difficult circumstances, Elena shrugged like it was nothing, looked down at Arminda, and smiled. In that moment I officially ran out of excuses for not caring for children in need.

Women aren’t the problem; they are the solution.

In the rural region of Colomi, we met a brave group of women who, together, changed their community’s esteem for children with special needs. When World Vision first began working in Colomi just two years ago, aid workers began by asking the women there what they most wanted to change about their community. The answer surprised the aid workers. The women said that, more than anything, they wanted to learn how to care for children with special needs.

In countries like Bolivia, children with special needs are so stigmatized and misunderstood that their mothers are often blamed for their illnesses.

“They told me that I must have been drinking while I carried the baby,” one mother told us, weeping openly. “But I was not drinking. I took care of my child, like any mother would. When he was born, I carried him on my back, even when I was working in the fields.”

“Some [special needs] children were being totally neglected,” another mother said. “They had to drag themselves across the floor because they could not walk. Some were simply left for dead.”

We heard stories of children who had been locked in rooms for weeks without being bathed or cared for, others who had been beaten nearly to death, and still more who had been abandoned because of fear and superstition.

Before World Vision came to Colomi, the mothers tried to organize. They formed a support group, where they exchanged stories and ideas, but they lacked basic information about how to care for their children with special needs and faced nearly constant ridicule from neighbors who said they were wasting their time.

So at these mothers’ request, the first major project undertaken by World Vision in Colomi was to establish a special needs center in its most populous community. There, children receive hearing aids, prosthetics, access to lifesaving surgery, and an education. Mothers gather each week to learn more about their children’s conditions and to offer support to one another. The facility still needs additional funding (when we were there, they had to lift children in wheelchairs up and down the stairs), but the sound of laughter echoes continually off the cement walls.

Women aren’t the problem; they are the solution.

In Bolivia I understood in a way I hadn’t before that women are capable of changing the world. Sometimes, all they need are the right tools. Cinda needed water. Marta need a sewing machine. Elena needed a few dozen guinea pigs. The women of Colomi needed only to be heard.

But I needed things too. I needed to be blessed by these women,

to be challenged by them, to be embraced and made uncomfortable by them.

What I love about the ministry of Jesus is that he identified the poor as blessed and the rich as needy . . . and then he went and ministered to them both. This, I think, is the difference between charity and justice. Justice means moving beyond the dichotomy between those who need and those who supply and confronting the frightening and beautiful reality that we desperately need one another.

That’s what I love about the Kingdom: For the poor, there is food. For the rich, there is joy. For all of us, there is grace.

READ MORE ONLINE:

“Greenlife”— http://rachelheldevans.com/greenlife