The Cambridge Companion to the Piano

The Cambridge Companion to the Piano is an informative and practical guide to one of the world’s most popular instruments. This collection of specially commissioned essays offers an accessible introduction to the history of the piano, performance styles and its vast repertory. Part 1 reviews the evolution of the piano, from its earliest forms up to the most recent developments, including the acoustics of the instrument, and the history of its performance. Part 2 explores the varied repertory in its social and stylistic contexts, up to the present, with a final chapter on jazz, blues and ragtime. The Companion also contains a glossary of important terms and will be a valuable source for the piano performer, student and enthusiast.

Cambridge Companions to Music

The Cambridge Companion to Brass Instruments

Edited by Trevor Herbert and John Wallace

0 521 56243 7 (hardback)

0 521 56522 7 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet

Edited by Colin Lawson

0 521 47066 8 (hardback)

0 521 47668 2 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to the Recorder

Edited by John Mansfield Thomson

0 521 35269 X (hardback)

0 521 35816 7 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to the Violin

Edited by Robin Stowell

0 521 39923 8 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to the Organ

Edited by Nicholas Thistlethwaite and Geoffrey Webber

0 521 57309 2 (hardback)

0 521 57584 2 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to the Saxophone

Edited by Richard Ingham

0 521 59348 4 (hardback)

0 521 59666 1 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to Bach

Edited by John Butt

0 521 45350 X (hardback)

0 521 58780 8 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to Berg

Edited by Anthony Pople

0 521 56374 7 (hardback)

0 521 56489 1 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to Chopin

Edited by Jim Samson

0 521 47752 2 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to Handel

Edited by Donald Burrows

0 521 45425 5 (hardback)

0 521 45613 4 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to Schubert

Edited by Christopher Gibbs

0 521 48229 1 (hardback)

0 521 48424 3 (paperback)

The Cambridge Companion to the

PIANO

![]()

EDITED BY

David Rowland

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo

Cambridge University Press

The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK

Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521474702

© Cambridge University Press 1998

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 1998

Third printing 2004

A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data

The Cambridge companion to the piano/edited by David Rowland.

p. cm. – (Cambridge companions to music)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0 521 47470 1 (hardback) ISBN 0 521 47986 X (paperback)

1. Piano. I. Rowland, David, Dr. II. Series.

ML650.C3 1998

786.2–dc21 97–41860 CIP MN

ISBN-13 978-0-521-47470-2 hardback

ISBN-10 0-521-47470-1 hardback

ISBN-13 978-0-521-47986-8 paperback

ISBN-10 0-521-47986-X paperback

Transferred to digital printing 2006

Contents

Bibliographical abbreviations and pitch notation

Introduction David Rowland

Part one · Pianos and pianists

1 The piano to c. 1770 David Rowland

2 Pianos and pianists c. 1770–c. 1825 David Rowland

3 The piano since c. 1825 David Rowland

4 The virtuoso tradition Kenneth Hamilton

5 Pianists on record in the early twentieth century Robert Philip

6 The acoustics of the piano Bernard Richardson

7 Repertory and canon Dorothy de Val and Cyril Ehrlich

8 The music of the early pianists (to c. 1830) David Rowland

9 Piano music for concert hall and salon c. 1830–1900 J. Barrie Jones

10 Nationalism J. Barrie Jones

11 New horizons in the twentieth century Mervyn Cooke

12 Ragtime, blues, jazz and popular music Brian Priestley

Figures

1.3 Clavichord by Christian Gotthelf Hoffmann, Ronneburg, 1784 (Cobbe Foundation).

1.4a Square piano by Zumpe, London, 1766 (Emmanuel College, Cambridge).

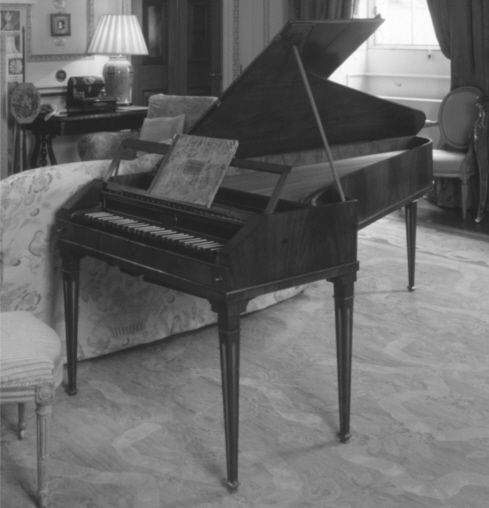

1.5 Grand piano by Americus Backers, London, 1772 (Russell Collection, Edinburgh).

2.1 Grand piano, c. 1795, Stein school, South Germany (Cobbe Foundation).

2.2a ‘Viennese’ grand piano action by Rosenberger, Vienna, c. 1800.

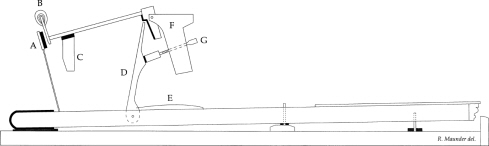

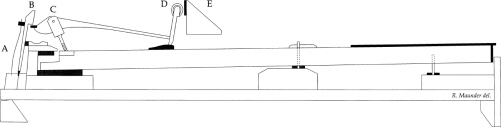

2.2b Diagram of the action in Figure 2.2a. A.

2.3a English grand piano action by Broadwood, London, 1798.

2.3b Diagram of the action in Figure 2.3a.

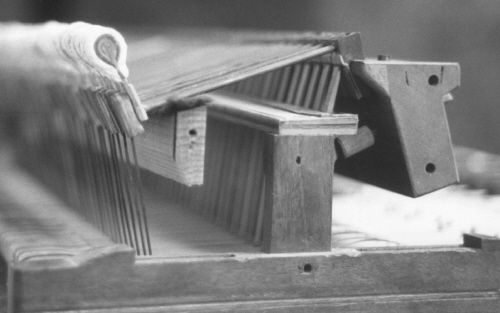

2.4 Reconstruction by Richard Maunder of Mozart’s Walter piano with pedalboard.

2.5 Grand piano by Graf, Vienna, c. 1820 (Cobbe Foundation).

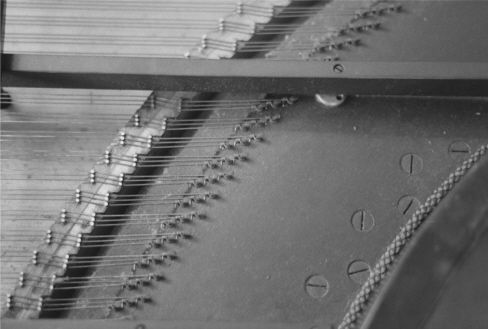

2.6 Moderator device on a ‘Viennese’ grand piano c. 1800.

2.7 Bassoon device on a grand piano by Streicher, Vienna, 1823 (Cobbe Foundation).

3.1 Grand piano by Stodart, London, c. 1822 (Faculty of Music, Cambridge University).

3.4 Broadwood square piano, 1858 (Finchcocks Collection).

3.5 Upright grand piano by Jones, Round and Co., London, c. 1810 (Finchcocks Collection).

3.6 Cabinet piano by Broadwood, London, c. 1825 (Richard Maunder).

3.7 Action of cabinet piano by Broadwood, London, c. 1825 (Richard Maunder).

3.8 ‘Cottage’ piano by Dettmar & Son, London, c. 1820 (Richard Maunder).

4.1 Statuette of Thalberg by Jean-Pierre Dantan (Musée Carnavalet, Paris).

4.2 Statuette of Liszt by Jean-Pierre Dantan (Musée Carnavalet, Paris).

5.1 Steinway grand piano with ‘Duo-Art’ reproducing mechanism, 1925.

6.1 Plan view of a Steinway concert grand piano, model D (9 foot) (Steinway & Sons).

6.3 Side view of the action of a modern grand piano. Reproduced from Askenfelt, Acoustics , p. 40.

6.4 Examples of wave-forms of middle c 1 (fundamental frequency 262 Hz) on a piano.

6.5 The first three modes of vibration of a stretched string using a ‘slinky spring’.

7.1 Extract from a catalogue by Goulding and d’Almaine, London, c .1830.

8.1 Steibelt, An Allegorical Overture (1797), title page.

8.2 Steibelt, An Allegorical Overture (1797), p. 8.

Music examples

2.1 Mozart, Piano Concerto in D minor, K466, first movement, bars 88–91 (piano part).

2.2 Mozart, Rondo in A minor, K511, bars 85–7.

2.3 Steibelt, Mélange Op. 10, p. 6.

2.4 Steibelt, Concerto Op. 33, p. 12.

4.2 J. S. Bach, Goldberg Variations, final aria, bars 1–4 (Bärenreiter Verlag).

4.3 Busoni’s arrangement of Ex. 4.2.

4.4 Grainger, Rosenkavalier ramble , bars 1–6 (Adolph Fürstner).

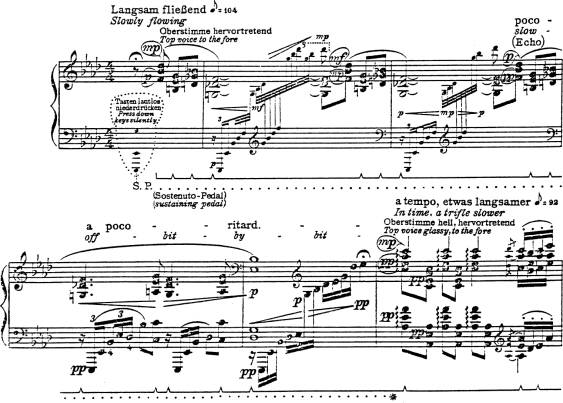

5.2 Bartók, Suite Op. 14, first movement, bars 1–12.

5.3 Bartók, Suite Op. 14, fourth movement, bars 22–3. Bartók’s rubato .

5.4 Chopin, Nocturne in E ♭ , Op. 9 No. 2. Rosenthal’s rubato .

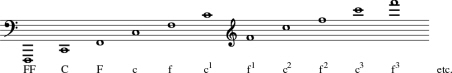

6.1 The first eight harmonics of a harmonic series based on C.

7.1a Schubert, Impromptu Op. 90 No. 3 (Bärenreiter, 1984).

7.1b Schubert, Impromptu Op. 90 No. 3 (Schloesser, 1890).

8.1 J. C. Bach, Sonata Op. 5 No. 3, bars 1–4.

8.2 C. P. E. Bach,‘Prussian’ Sonata No. 1, slow movement, bars 1–8

8.3 Field, Nocturne No. 1, bars 1–2.

9.1 Mendelssohn, Rondo capriccioso Op. 14, bar 227.

9.2 Beethoven, Sonata Op. 2 No. 3, bar 252.

9.4 Brahms, Ballade Op. 10 No. 2.

9.5 Brahms, Intermezzo Op. 117 No. 2.

9.6 Chopin, Prelude in B, bars 14–15.

10.1 Chopin, Mazurka Op. 30 No. 4, bars 125–33 (G. Henle Verlag).

10.2 Chopin, Mazurka Op. 17 No. 4, end.

10.3 Chopin, Mazurka Op. 68 No. 2.

10.4 Chopin, Mazurka Op. 17 No. 4, bar 18 (G. Henle Verlag).

10.5 Liszt, Csárdás macabre , bars 58–65 (Editio Musica Budapest).

11.1 Beethoven, Sonata Op. 31 No. 2, first movement.

11.2 Debussy, ‘Pagodes’ from Estampes , bars 39–40 (Durand et Fils).

11.3 Messiaen, ‘La colombe’ from Préludes , end (Durand & Cie).

11.4 Bartók, Second Piano Concerto, slow movement, bars 88–93 (piano part only) (Universal Edition).

11.5 Debussy, L’isle joyeuse , end (Durand et Fils).

11.6 Schoenberg, Three Pieces Op. 11 No. 1, bars 14–16 (Universal Edition).

11.7 Webern, Variations Op. 27 No. 2 (Universal Edition).

12.1 Joplin, ‘Maple Leaf rag’, first edition (New York Public Library).

Notes on the contributors

Mervyn Cooke was for six years a Research Fellow and Director of Music at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, before being appointed Lecturer in Music at the University of Nottingham. His publications include Cambridge University Press handbooks on Britten’s Billy Budd and War Requiem , a monograph Britten and the Far East and two volumes devoted to jazz (Thames and Hudson); he is currently involved in the preparation of an edition of Britten’s letters and editing the Cambridge companion to Britten . He is also active as a pianist and composer, his compositions having been broadcast on BBC Radio 3 and Radio France, and performed at London’s South Bank and St John’s Smith Square.

Cyril Ehrlich is Emeritus Professor of Social and Economic History at the Queen’s University Belfast and has also been Visiting Professor in Music at Royal Holloway and Bedford New College. He has written extensively on musical matters in his books First Philharmonic: a history of the Royal Philharmonic Society ; Harmonious alliance: a history of the Performing Right Society and The music profession in Britain since the eighteenth century . His book The piano: a history has become essential reading for piano historians.

Kenneth Hamilton is well known as a concert pianist and writer on music. He has performed extensively both in Britain and abroad, specialising mainly in the Romantic repertory, and has broadcast on radio and television. His book on Liszt’s Sonata in B minor is published by Cambridge University Press, and he is currently working on a large-scale study of Liszt and nineteenth-century pianism. He has premiered many unpublished virtuoso works by Liszt and others (some in his own completion), and is at present a member of the music department of Birmingham University.

Barrie Jones is a Lecturer in Music at the Open University. His main interests lie in the nineteenth century, particularly keyboard music. He has made extensive contributions to several Open University courses, has translated and edited Fauré’s letters, Gabriel Fauré: a life in letters (Batsford, 1989) and published a number of articles on Schumann, Liszt, Granados and Parry. He continues to perform regularly on the piano.

Robert Philip is a producer at the BBC’s Open University Production Centre, and a Visiting Research Fellow at the Open University. He has written and presented many programmes for BBC Radio 3, often on the subject of early recordings. His book Early recordings and musical style (Cambridge, 1992) was the first large-scale survey of performance practice in the early twentieth century. He has also contributed chapters to Performance practice , ed. Howard Mayer Brown and Stanley Sadie (London, 1989) and Performing Beethoven , ed. Robin Stowell (Cambridge, 1994). He is currently writing A century of performance , a survey of trends in twentieth-century performance.

Brian Priestley is a performer, writer and broadcaster who taught jazz piano for many years at University of London, Goldsmith’s College. Now an Associate Lecturer at the University of Surrey, he is a contributor to the International directory of black composers and to the New Grove dictionaries of American music and of jazz, and has written several widely praised biographies. For the best part of twenty-five years, he has presented a weekly radio programme, currently on Jazz FM.

Bernard Richardson is currently a Lecturer in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Wales at Cardiff. For the past twenty years he has undertaken scientific research into the acoustics of stringed musical instruments. These research activities stem from a long-standing passion for making and playing musical instruments. He lectures world-wide on the subject and has contributed to The Cambridge companion to the violin , The encyclopedia of acoustics and many journals.

David Rowland is a lecturer in music and Sub-Dean in the Faculty of Arts at the Open University and Director of Music at Christ’s College, Cambridge. His book, A history of pianoforte pedalling , was published in 1993 and he has contributed chapters and articles on aspects of piano performance and repertory history to The Cambridge companion to Chopin , Chopin studies 2 , Performing Beethoven and a number of journals. Since winning the St Albans International Organ Competition in 1981 he has continued to perform and record extensively on the organ, harpsichord and early piano.

Dorothy de Val completed a doctoral dissertation at King’s College London on the development of the English piano and has since taught music history at the Royal Academy of Music. She is a contributor to the Haydn Companion , published by Oxford University Press. Her interests include nineteenth-century London concert life, women pianists and the beginnings of the early music and folk-song revival in Britain in the late nineteenth century. She now resides and lectures in Oxford.

Acknowledgements

A wide-ranging volume such as this could not have been written without substantial help from a number of individuals and institutions. I would therefore like to thank Vicki Cooper, Commissioning Editor for the volume, for her ideas and help throughout the project. I would also like to thank Richard Maunder for many interesting hours discussing piano matters, for reading the drafts of my chapters and for his assistance with diagrams and illustrations. David Hunt has been of invaluable assistance in technical piano matters and has never hesitated to spend time on the telephone or in his workshop answering my questions. Cyril Ehrlich has also provided advice on piano history and read some of my drafts. All of the chapter authors have been most patient and co-operative in discussing details of their material with me and with each other and making changes as necessary. Rosemary Kingdon of the Open University deserves thankful recognition for the many hours spent preparing the typescript of this volume.

A number of individuals and collections have kindly provided illustrative material. Details of the sources accompany the list of figures, but I would especially like to thank the following for their help in locating suitable photographs: Richard Burnett and William Dow at Finchcocks, Alec Cobbe of The Cobbe Foundation, Stewart Pollens of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Master and Fellows of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, the Faculty of Music, Cambridge University, the staff of the Russell Collection, Edinburgh.

I am grateful to a number of libraries for allowing me to use music in their possession, especially the Pendlebury Library and University Library in Cambridge and New York Public Library.

Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Ruth, and daughters, Kate, Hannah and Eleanor, for the many hours they have spent waiting for me to return home from the office.

Bibliographical abbreviations

The following abbreviations have been used:

AMZ

Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung

EM

Early Music

ML

Music & Letters

MQ

The Musical Quarterly

MT

The Musical Times

New Grove

Stanley Sadie (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (London, 1980)

Pitch notation When referring to keyboard compasses the following notation has been used, which is similar to, or identical with, that most commonly found in the literature on the keyboard:

DAVID ROWLAND

Introduction

The Cambridge companion to the piano brings together in a single volume a collection of essays which covers the history of the instrument, the history of its performance and a study of its repertory. Each chapter is written by a specialist with access to the most recent research on his or her topic, but all the authors have written accessibly, with the student of the instrument, or an enthusiastic amateur, in mind.

Chapters 1 –3 bring together as much up-to-date piano history as is possible in the space available. In recent years, some extremely important work has been published on the early history of the piano. Stewart Pollens’s The early pianoforte and Michael Cole’s The pianoforte in the Classical era between them provide a comprehensive survey of the technical developments which took place in the eighteenth century. These developments are summarised in chapters 1 and 2 along with information about the specific kinds of instrument played by the early pianists. Necessary technical terms are explained in the glossary at the end of the volume. The equivalent history of the piano in the first half of the nineteenth century is much less well documented and a new, detailed history of the piano in the nineteenth century is urgently needed. It is remarkable that Rosamond Harding’s book The piano-forte , first published as long ago as 1933, remains the standard text for this period. Nevertheless, new work is emerging in this field by scholars, curators and restorers and it has been possible to draw on much of this material for the brief history of the piano found in the remainder of chapter 2 and in chapter 3 . Cyril Ehrlich’s The piano: a history continues to be a major source of information for the piano industry in the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries

Many issues in the early performance history of the piano are intimately associated with the nature of the instruments themselves. It is not possible, for example, to assess whether Mozart composed some of his earlier music for the piano, or for the harpsichord or clavichord, without a knowledge of the general availability of pianos in Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century. Likewise, an understanding of the differences between English and ‘Viennese’ pianos is crucial to an understanding of some of the performance issues associated with the music of Beethoven and his contemporaries. For reasons such as these, the study of piano performance to c .1825 will be found alongside the history of the instrument in chapters 1 and 2 . The way in which later pianists played is investigated in two chapters. Chapter 4 assesses those pianists whose playing styles can be studied only through written sources – concert reviews, memoirs, letters and so on. Chapter 5 studies those pianists who belong to the recording era.

Part 1 of this volume, which deals only with instruments and performers, concludes with an examination of the precise way in which sound is generated in a modern grand piano, and how that sound is transmitted to an audience.

Part 2 concerns the repertory of the piano. Rather than devote single chapters to studies of the sonata, the concerto and so on, authors have written about the music in the wider context of its performance setting and stylistic development. The discussion begins in chapter 7 with an examination of the emergence of a ‘standard’ repertory in the nineteenth century (which continues to form the basis of the repertory for most modern pianists). Even by the early years of the century, an enormous volume of music had been written for the piano; yet only a small proportion of what was written came to be played by subsequent generations, and an even smaller proportion of it has come to be considered ‘canonic’ or ‘exemplary’. Chapter 7 explores how and why this was so.

Chapters 8 –10 examine the piano music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in some detail. The way in which composers wrote for the instrument at the time was shaped by a variety of factors. For early pianists such as Mozart the sonata was the most common vehicle for solo expression; yet within a generation, sonatas were no longer in widespread fashion and composers were beginning to concentrate their energies on shorter, ‘character’ or dance pieces. At least part of the reason for this change lay in the rapidly increasing public demand for shorter works, many of which were written for the burgeoning amateur market catered for by a growing publishing industry. At the same time, a distinctive piano style emerged which displaced a keyboard style capable of realisation on the harpsichord and clavichord as well as on the piano. Virtuosos of the piano emerged who achieved celebrity status in their public performances. These pianists wrote difficult concert études and concertos for themselves to play in public; but they also wrote more intimately for the salons in which they performed and for the amateur, domestic market (chapter 9 ). Within the concert and salon repertory towards the middle of the nineteenth century there was a strong interest in musical elements of eastern Europe (such as the Polish ingredients in Chopin’s music, or those from Hungary in Liszt’s). These and other nationalistic elements from, for example, Russia and Scandinavia, are reviewed in chapter 10 . The twentieth century has seen many new developments in piano writing. Many novel techniques emerged during the first half of the century (chapter 11 ) and there has been an increasing appreciation of the ‘popular’ styles of ragtime, blues and jazz (chapter 12 ). Many classically trained pianists now play music in these styles and the cross-over of ‘art’ music and ‘popular’ music styles can be seen in integrated works by composers such as Gershwin.

This volume, in common with all of the others in the Cambridge companion series, cannot claim to be comprehensive. Nevertheless, it will give the reader a breadth of information on the subject rarely found elsewhere, written by specialists who have made their own thorough studies.

PART ONE

Pianos and pianists

1

DAVID ROWLAND

The piano to c. 1770

Italy and the Iberian peninsula

Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1732) is generally credited with the invention of the piano in Florence at the end of the seventeenth century. Although some earlier accounts of keyboard actions survive, it is only from Cristofori that a continuous line of development can be drawn. 1

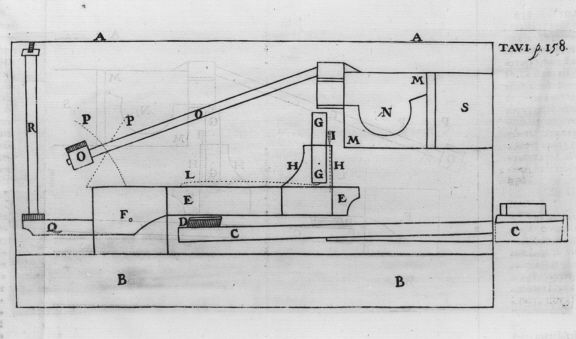

Cristofori entered the service of Prince Ferdinando de’ Medici in 1688 as curator and instrument maker. In this capacity he maintained harpsichords, spinets and organs and made a variety of keyboard (and possibly stringed) instruments. 2 His work on the piano may have begun as early as 1698, certainly by 1700, 3 and in 1709 or 1710 Scipione Maffei noted that Cristofori had ‘made three so far, two sold in Florence, one to Cardinal Ottoboni’. 4 In 1711 Maffei published a detailed description of Cristofori’s pianos, including a diagram of the action (Fig. 1.1 ). 5

Figure 1.1 Maffei’s diagram of Cristofori’s piano action from the Giornale de’letterati d’Italia , 5 (1711).

The action in Maffei’s diagram works in the following way: as the key (C) is depressed one end of the intermediate lever (E) – which pivots around the pin (F) – is raised. This causes the escapement (G) to push the hammer (O) towards the string (A). The escapement then ‘escapes’ from contact with the hammer and allows it to fall back to its resting position, on a silk thread (P). When the key is released, the escapement, which is hinged and attached to a spring (L), slides back into its resting position and the damper (R) – which had been lowered when the key was depressed – comes back into contact with the string in order to damp the sound.

Many aspects of piano design evidently continued to occupy Cristofori, since the three surviving pianos by him, dated 1720, 1722 and 1726, as well as a keyboard and action of c. 1725, differ from each other and from Maffei’s description in certain aspects of their mechanism and construction. Nevertheless, all of the existing instruments share certain characteristics: they are lightly constructed, compared with later pianos, and have small hammers (in two of the pianos, made only of rolled and glued parchment covered with leather). The instruments produce a gentle sound and their keyboard compass is just four octaves (1722, c. 1725 and 1726) or four and a half octaves (1720) – considerably smaller than the five octaves or so of the biggest harpsichords of the time.

Cristofori’s work was continued by his pupils, the most important of whom was probably Giovanni Ferrini (fl .1699(?)–1758) who, like his teacher, made harpsichords as well as pianos in Florence. 6 Indeed, his only surviving instrument with piano action is a combination harpsichord / piano, with an upper and lower manual operating the piano and harpsichord respectively. Such combination instruments continued to be popular throughout the period during which the relative merits of the two types of keyboard instrument were debated – until at least the 1780s. In the meantime, the fame of the Florentine makers spread to the Iberian peninsula, where other makers began to construct instruments based on Cristofori’s design. 7

Who used these early pianos, and for what purpose? Very little evidence has survived but it is likely that a number of well-known musicians encountered pianos in southern Europe during the early decades of the century. George Frederic Handel (1685–1759) may have seen Cristofori’s instruments in Florence and Rome. Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757) almost certainly played a number of Florentine pianos: he stayed in Florence for several months in 1702 and he taught Don Antonio of Portugal, the dedicatee of the first music known to be published for the piano – twelve sonatas by Lodovico Giustini (1685–1743), which appeared in Florence in 1732. He was also employed at the court of Maria Barbara of Spain, who owned five Florentine pianos, according to an inventory made in the year following Scarlatti’s death. 8 Farinelli, the famous castrato and Scarlatti’s colleague in Spain for twenty-two years, also owned a piano dated 1730, according to Burney. 9

Figure 1.2 Piano by Cristofori, 1720.

From the start, the piano seems to have been regarded as a solo instrument. Maffei wrote that ‘its principal intention’ was ‘to be heard alone, like the lute, the harp, the six-stringed viol, and other most sweet instruments’. 10 Giustini’s sonatas were written for solo piano, and Farinelli played solos on his piano when Burney visited him in 1770. It has also been suggested that a significant proportion of Scarlatti’s sonatas were written for the piano, though the evidence cannot be regarded as conclusive. 11 Nevertheless, early pianos had certain shortcomings as solo instruments and Maffei was the first to voice a common complaint of the eighteenth century: ‘this instrument does not have a powerful tone, and is not quite so loud’ as the harpsichord. 12 Perhaps it was this problem that caused Maria Barbara to convert two of her Florentine pianos into harpsichords. 13 Whatever the extent of the piano’s use for solo performances, it also had some success in accompanying one or more other instruments in chamber music: Maffei and several other eighteenth-century writers recommended its use in this way.

Germany and Austria

The history of the piano in German-speaking lands is complex. Christoph Gottlieb Schröter (1699–1782) claimed to have invented a keyboard action in 1717 for an instrument in which the strings were struck by hammers. 14 The inspiration for Schröter’s invention was Pantaleon Hebenstreit’s (1669–1750) performance on the ‘pantalon’. Hebenstreit’s pantalon was an enlarged dulcimer measuring about nine feet in length which had one set of metal strings and one of gut. It was played with wooden beaters held in the hands, and had no dampers. The pantalon was reputed to be extremely difficult to play and expensive to maintain, but its sound was much admired and a small, elite group of performers toured Europe throughout much of the eighteenth century. 15 By designing a hammer action operated from a keyboard Schröter no doubt wished to capture the sound of the pantalon while avoiding the strenuous efforts required of a performer. He presented his solution in the form of two hammer-action models – one striking the strings from below, the other from above – to the Elector of Saxony in Dresden in 1721. However, no complete instrument ever seems to have been made, and Schröter’s contribution to the development of the hammer-action instruments with keyboard was probably confined to some articles in eighteenth-century German journals. The idea of the keyed pantalon lived on, however. A number of instruments survive with bare wooden hammers which are called ‘pantalon’ in the literature of the time. The term pantalonzug (‘pantalon stop’) is also commonly found to describe the stop or lever which removed the dampers from the strings (equivalent to the right pedal on a modern piano), in imitation of the undamped sound of the pantalon. 16

Early piano making in Germany seems to have been concentrated in the area just south of Leipzig. Gottfried Silbermann (1683–1753) worked in Freiberg and Christian Ernst Friederici (1709–80), reputedly Silbermann’s pupil, worked about sixty miles to the west, in Gera. Silbermann was making pianos in the early 1730s. 17 No details of these instruments survive, but it is possible that they followed Cristofori’s design, published by Maffei in 1711 and subsequently in German translation in Mattheson’s Critica musica (Hamburg, 1725). One of Silbermann’s early instruments evidently failed to satisfy Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) who, according to his pupil Johann Friedrich Agricola, had ‘praised, indeed admired, its tone; but he had complained that it was too weak in the high register, and was too hard to play’. Agricola goes on to describe how Silbermann was angered at Bach’s reaction, but decided nevertheless

not to deliver any more of these instruments, but instead to think all the harder about how to eliminate the faults Mr. J. S. Bach had observed. He worked for many years on this. And that this was the real cause of the postponement I have the less doubt since I myself heard it frankly acknowledged by Mr. Silbermann. Finally, when Mr. Silbermann had really achieved many improvements, notably in respect to the action, he sold one again to the Court of the prince of Rudolstadt. Shortly thereafter His Majesty the King of Prussia had one of these instruments ordered, and, when it met with His Majesty’s Most Gracious approval, he had several more ordered from Mr. Silbermann. 18

In fact, according to Forkel, 19 the King ordered a total of fifteen pianos from Silbermann, and prior to the second world war three of these instruments still existed. Now only two of the King’s pianos survive, one of them dated 1746. In addition, however, there is another grand piano by Silbermann dated 1749 in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nürnberg. 20

The actions of the surviving Silbermann pianos resemble the extant Cristofori instruments extremely closely and suggest that Silbermann copied one of Cristofori’s later pianos. The instruments by the two makers differ in some respects, however. Not surprisingly, the appearance of the case of Silbermann’s pianos resembles that of contemporary German harpsichords, as does the range of the instruments – just under five octaves with FF as the lowest note. The devices to modify the sound of the instrument are also different. Cristofori included just one on his instruments – a pair of stop knobs to shift the keyboard laterally, thereby causing the hammer to hit only one string, the precursor of the modern una corda and probably a legacy from Italian harpsichords which often had two registers operated by means of stops. Silbermann included two tone-modifying devices, neither of which was the una corda . One was a stop knob which operated a mechanism to introduce small pieces of ivory between the hammers and the strings, producing a harpsichord-like sound. The other was a stop which was used to raise the dampers from the strings – the precursor of the modern damper or sustaining pedal.

According to Agricola, Silbermann’s later pianos were approved by J. S. Bach, whose visit to Frederick the Great’s court in 1747 was also reported in a contemporary newspaper. The King evidently

went at Bach’s entrance to the so-called forte and piano, condescending also to play, in person and without any preparation, a theme to be executed by Capellmeister Bach in a fugue. This was done so happily by the aforementioned Capellmeister that not only His Majesty was pleased to show his satisfaction thereat, but also all those present were seized with astonishment. 21

Further evidence of Bach’s approval is his signature on a voucher for the sale of one of Silbermann’s pianos to Count Branitzky of Poland dated 9 May 1749. 22 Despite Bach’s fascination with the piano, however, the instrument cannot have been of any significance for his keyboard music written before the 1740s – Silbermann’s improved pianos were not made before then.

By the middle of the eighteenth century German pianos were being made in forms other than the conventional grand. The upright grand came to be associated with northern European makers, especially Christian Ernst Friederici, although a similar instrument by the southern European maker Domenico del Mela (1683–c .1760?), of 1739, survives. In 1745 Friederici published an engraving of one of his upright grands and at least one, possibly more, of his is still in existence. 23 Friederici is also credited with the invention of the square piano, which was being made in Germany around the middle of the eighteenth century. 24 Square pianos were much smaller and cheaper than either the conventional or upright grand, and were ultimately to become extremely popular in the home, but in mid-eighteenth-century Germany they had a formidable rival in the clavichord, which keyboard players continued to use until at least the end of the century.

Much of what happened to the development of the piano in German-speaking lands in the third quarter of the eighteenth century is shrouded in uncertainty. One of the most important makers during this time was evidently Johann Heinrich Silbermann (1727–99; Gottfried’s nephew) in Strasbourg, some of whose pianos from the 1770s survive. 25 His instruments share many features of those made by his uncle, Gottfried Silbermann: pianos by both makers have transposing devices which are operated by moving the keyboard laterally and the actions of both makers are similar, even to the extent of having hammers made from rolled parchment covered with leather (rather than wood and leather), as on two of Cristofori’s pianos. But apart from these instruments, the absence of other grands as well as the lack of detail in contemporary literature, make it impossible to describe how, when and indeed if any developments took place. One thing at least is clear, however, the piano did not immediately take the place of either the clavichord or the harpsichord in the affections of keyboard players. On the contrary, the piano seems to have been regarded as just one possibility among others. Many sources could be quoted to illustrate this point. One of the earliest, and probably the best known, is Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–88), who wrote in 1753:

Figure 1.3 Clavichord by Christian Gotthelf Hoffmann, Ronneburg, 1784.

something remains to be said about keyboard instruments. Of the many kinds, some of which remain little known because of defects, others because they are not yet in general use, there are two which have been most widely acclaimed, the harpsichord and the clavichord. The former is used in ensembles, the latter alone. The more recent pianoforte, when it is sturdy and well built, has many fine qualities, although its touch must be carefully worked out & It sounds well by itself and in small ensembles. Yet, I hold that a good clavichord, except for its weaker tone, shares equally in the attractiveness of the pianoforte and in addition features the vibrato and portato which I produce by means of added pressure after each stroke. It is at the clavichord that a keyboardist may be most exactly evaluated. 26

C. P. E. Bach must have written this after several years’ experience of Silbermann’s pianos at Frederick the Great’s court. Further evidence for the limited progress of the piano in the region comes from Jacob Adlung, who spent all of his adult life in Erfurt, not far from Gera, where Friederici worked, and even closer to Rudolstadt, where Silbermann had sent a piano in the early or mid 1740s. In 1758 Adlung wrote that he had not yet seen a piano, although he was aware that the instrument was known in a number of places, and he knew of Friederici. 27

Figure 1.4a Square piano by Zumpe, London, 1766.

Figure 1.4b Detail of Zumpe piano showing (inside the case, to the left) the sustaining handstop which raises the bass dampers from the strings, the small, leather-covered hammers and (at the top of the photograph) the wooden levers on which the dampers are mounted.

The slow progress of the piano is underlined by Charles Burney’s account of his journey to Germany and Austria in 1772 which reveals much concerning keyboard history and performance. Over a period of several months he heard many keyboard players, both in public and in private, but there are relatively few accounts of performances on the piano. Only harpsichords and harpsichordists are mentioned in his account of Coblenz and Frankfurt. In Ludwigsberg Burney met Christian Friedrich Schubart (1739–91) who ‘played on the clavichord, with great delicacy and expression’ and then later in the day ‘played a great deal on the Harpsichord, Organ, Piano forte, and Clavichord’. 28 In Munich Burney heard several harpsichord performances, but none on the piano, and in Vienna, out of a total of some fifteen accounts of keyboard playing in public and in private, only one was on a piano: a ‘child of eight or nine years old’ played ‘upon a small, and not good Piano forte’. 29 In Czaslau Burney heard clavichords and in Dresden a harpsichord, but it was only when he arrived in Berlin that he heard pianos again. Agricola ‘received me very politely; and though he was indisposed, and had just been blooded, he obligingly sat down to a fine piano forte , which I was desirous of hearing and touched it in a truly great style’. 30 Of Johann Philipp Kirnberger (1721–83), however, Burney noted that

the harpsichord, which was his first, is likewise his best instrument & He played at my request upon a clavichord, during my visit, some of his fugues and church music & After this he had the complaisance to go with me to the house of Hildebrand, the best maker of harpsichords, and piano-fortes, in Berlin. 31

The mention of Hildebrand as a piano maker is interesting, since it demonstrates that by this time other makers besides the Silbermanns and Friederici had set up in business. Indeed, a brief article published in 1769 reports that Johann Andreas Stein (1728–92), who was to become one of the most important late-eighteenth-century piano makers, had already been working to improve the piano for the previous ten years. 32 Stein had worked with the Strasbourg Silbermanns in 1748 and 1749 and is usually associated with the so-called ‘Viennese’ action (see chapter 2 ).

England

The early history of the piano in England is sketchy. According to Charles Burney ‘The first [piano] that was brought to England was made by an English monk at Rome, Father Wood, for an English friend (the late Samuel Crisp &)’. 33 Crisp spent some time in Italy in the late 1730s and it seems likely that Father Wood, of whom nothing is known, made a copy of a Cristofori-type piano. The action of Wood’s piano cannot have been very sophisticated since ‘the touch and mechanism were so imperfect that nothing quick could be executed upon it, yet the dead march in Saul, and other solemn and pathetic strains, when executed with taste and feeling by a master a little accustomed to the touch, excited equal wonder and delight to the hearers’. 34 Burney relates how Crisp sold the piano to Fulke Greville for 100 guineas and elsewhere describes how he became accustomed to the touch of the instrument during a prolonged stay in Greville’s house, which must have been in the late 1740s. 35 Again, according to Burney, this piano remained unique in England ‘till Plenius & made a piano-forte in imitation of that of Mr. Greville. Of this instrument the touch was better, but the tone very much inferior.’ 36 Roger Plenius (1696–1774) came to England having worked for some time in Amsterdam. He was in London by 1741 and the records of his bankruptcy in 1756 show that in December 1741 he borrowed £1100, presumably to set up in business. After making his copy of Greville’s piano Plenius evidently asked Burney to demonstrate it in public, but Burney declined because ‘I had other employmt s w ch I liked better than that of a shewman’. 37 Presumably this discussion took place after Burney returned to London from Greville’s estate and before he went to live in Kings Lynn, that is, in the years 1749–51, or after Burney again returned to London in 1760.

Meanwhile an English cleric, William Mason journeyed to Hanover where he purchased a combination piano/harpsichord. On 27 June 1755 he wrote to his friend Thomas Gray: ‘Oh, Mr Gray! I bought at Hamburg such a pianoforte, and so cheap! It is a harpsichord too of two unisons, and the jacks serve as mutes when the pianoforte stop is played, by the cleverest mechanism imaginable.’ 38 Unfortunately, no details of this instrument survive.

In 1763 Frederic Neubauer advertised ‘harpsichords, piano-fortes, lyrachords and claffichords’ for sale in London. 39 No records survive to show whether or not he sold any instruments, but the mention of pianos in the same advertisement as lyrachords possibly suggests the work of Plenius: the lyrachord was a peculiar invention of his, and he had probably made a piano by this time.

From 1766 there is incontrovertible evidence of piano making in London in the form of some existing square pianos by the German émigré Johann Christoph Zumpe (fl .1735–83), who had settled in London in about 1760 (Figs. 1.4a and 1.4b ). Zumpe began to make pianos in the mid 1760s and within a very short time his instruments, as well as similar models by other makers such as Johann Pohlman (fl .1767–93), had become extremely popular. This was doubtless partly due to their price – half that of a single manual harpsichord and much less than a grand piano (see below) – as well as their touch sensitivity, though that was limited by today’s standards. A nineteenth-century member of the Broadwood family summed up the characteristics of these instruments well:

They were in length about four feet, the hammers very lightly covered with a thin coat of leather; the strings were small, nearly the size of those used on the Harpsichord; the tones clear, what is now called thin and wiry; – his object being, seemingly, to approach the tones of the Harpsichord, to which the ear, at that period, was accustomed & Beyer, Buntebart and Schoene – all Germans – soon after this introduction by Zumpe, began making Pianos, and by enlarging them, produced more tone in their instruments. 40

Johann Christian Bach (1735–82) quickly took advantage of the new interest in square pianos. On 17 April 1766 the London Public Advertiser announced the publication of Bach’s ‘Six Sonatas for Piano Forte or Harpsichord’ Op. 5, which were presumably intended for performance on Zumpe’s instruments. Bach also seems to have become an agent for Zumpe: on 4 July 1768 his bank account at Drummond’s shows a payment of £50 to Zumpe (enough, probably for three pianos – see the prices quoted below) and Bach helped Madame Brillon in Paris to acquire an English piano sometime before Burney visited her in 1770. 41

The grand piano took rather longer than the square to come into popular use in England. Americus Backers (fl .1763–78) was the first maker of significance. He probably began to make grands in the late 1760s, and an instrument of his dated 1772 still exists (Fig. 1.5 ). 42 By the time Backers made this instrument he had refined the action to the extent that other makers of English grands such as John Broadwood (1732–1812) copied its essential details. The 1772 Backers is bichord throughout (unlike some of his later pianos – see Burney’s letter below) and has the two pedals that were to be standard on English grand pianos thereafter; a damper or sustaining pedal and a una corda pedal. Backers appears to have made about sixty pianos before his death in January 1778 and for most of this time he seems to have been the only maker of grand pianos in London. One of his instruments was probably rented by J. C. Bach, who made a payment of ten guineas to Backers on 17 February 1773. Backers also earned Burney’s respect, judging from the latter’s comments which also sum up the state of the English piano industry in 1774. Burney wrote to Thomas Twining on 21 January:

Figure 1.5 Grand piano by Americus Backers, London, 1772.

[Ba]ckers makes the best Piano Fortes, but they come to 60 or 70 £, with 3 unisons – & of the Harpsichord size – Put them out of the question, & I think Pohlman the best maker of the small sort, by far. Z [u ]mpe WAS the best, but he has given up the business. – Pohlmann then for 16 or 18 Guineas makes charming little instruments, sweet & even in Tone, & capable of great variety of piano & forte, between the two extremes of pianissimo & fort mo . Those for 16 Gn s only go to double G, without a double G ♯ ; but for the 2 Gn s more he has made me two or three with an octave to double F & F ♯ with a double G ♯ . 43

The piano was adopted for public performance relatively quickly in England. The first recorded occasion was 16 May 1767, when Charles Dibden (1745–1814) accompanied Miss Brickler in a ‘favourite Song from Judith … on a new instrument called piano-forte’ at Covent Garden. 44 The first solo performance seems to have been a piano concerto played by James Hook (1746–1827) on 7 April 1768, possibly on a Backers grand. 45 Within just a few years, most of the prominent keyboard players in London were performing in public on the piano. There were notable exceptions, however. Ironically one was Muzio Clementi (1752–1832), the so-called ‘father of the pianoforte’. Despite the fact that his publications of the 1770s all stipulate the piano or harpsichord on their title pages, six out of seven public performances that he gave in the period 1775–80, and for which it is possible to identify the keyboard instrument, were given on the harpsichord. 46

The piano may have featured relatively early in professional concerts in London. In a domestic setting, however, and outside of the capital, the harpsichord persisted much longer. This is illustrated in the number of harpsichords still made in the 1770s and 1780s by firms such as Broadwood (see also chapter 2 ). Some insight into domestic music making is also to be found in the account books of Thomas Green, a keyboard tuner in Hertford: although he tuned a piano as early as 1769, he continued to tune and purchase harpsichords right up to the end of his career in 1790. 47

France

Apart from some drawings of hammer actions submitted to the Académie Royale in Paris in 1716 by Jean Marius, the first reference to a piano in France is an advertisement dated 20 September 1759 which describes in some detail the ‘newly-invented harpsichord called piano et forte ’. 48 Nine months previously, the keyboard player Johann Gottfried Eckard (1735–1809) had arrived in Paris with Johann Andreas Stein, both having visited the Silbermann workshop in Strasbourg en route . Perhaps Eckard, who stayed in Paris, had begun to act as Silbermann’s agent. Whether or not this was so, there is clear evidence that Silbermann’s pianos became known in Paris in the 1760s. An advertisement for one of his pianos, with transposing device, appeared in the Avant Coureur in April 1761. In 1769 an article in Hiller’s Nachrichten reported that ‘Mr. Daquin & organist at Notre Dame’ had a Silbermann piano which he compared with his harpsichord: ‘the harpsichord is the bread, and the fortepiano a delicate dish, of which one will soon be sick’. 49 Later eighteenth-century dictionary articles also relate how Silbermann’s pianos were especially well known in France.

Two grand pianos of the 1770s by J. H. Silbermann survive, and it was probably for this type of instrument that Eckard published the first music for the piano in France – his Op. 1 Sonatas, which were advertised in the French press on 28 April 1763. The title page mentions only the harpsichord but an explanatory note inside mentions the possibility of harpsichord, piano or clavichord. His Op. 2 was advertised for harpsichord or piano in the following year. By this time, in addition to Silbermann’s imported instruments, there is evidence of grands being produced in Paris by local makers: an inventory detailing the belongings of Claude-Bénique Balbastre’s (1727–99) wife, of 1763, mentions a ‘clavecin with hammers’ by François-Etienne Blanchet (c .1730–66), 50 in whose workshop was found a similar, but unnamed, instrument in 1766. 51 Blanchet’s work was continued by Pascal Taskin (1723–93), who was making grand pianos at least as early as the mid 1770s, and some of whose pianos survive. 52 Other Parisian makers followed, such as Jacques Goermans (1740–89). 53

Makers of square pianos in London quickly made inroads into the Parisian market: J. C. Bach acted as an agent for Zumpe in the sale of at least one square piano (see above, p. 17) and we know from Burney that Zumpe himself had been in Paris in 1770. 54 Burney himself advised Diderot on the cost of a Zumpe square which was quoted at the apparently inflated price of twenty-eight guineas. 55 The number of imports from England at this time can be judged from the comments in the French press. The Avant Coureur of 2 April 1770 reported a performance on a new piano designed by Virbès, describing the instrument as ‘in the shape of those from England’. The same newspaper printed a poem entitled ‘L’Arrivée du forte piano’ (‘The arrival of the forte piano’) which read:

What, my dear friend, you come to me from England?

Alas! How can we declare war on her? 56

In 1773 the French music publisher Cousineau announced that he had ‘several excellent English pianos’ for sale, 57 and a number of later sources made it clear that a large proportion of pianos sold in France in the 1770s and 1780s came from England.

Far from attempting to resist this trend, some French keyboard makers themselves imported English square pianos. In 1777 Pascal Taskin evidently owed money – sufficient for two square pianos – to Frederick Beck (fl .1756–98) in London, 58 and in 1784 the same maker ordered four more pianos from Broadwood. 59 Such was the popularity of English squares that by the time of the Revolution the vast majority of pianos owned by the nobility were made by Zumpe, his successor Schoene and others such as Beck and Pohlman. 60 In the face of this flood of imports a number of French makers began to produce copies of English square pianos. The first appears to have been Johann Kilian Mercken (1743–1819) – a 1770 piano of his survives. Mercken was followed by several other Parisian makers, one of whom was Sebastian Erard (1752–1831), whose firm was to become very influential in the subsequent history of the piano (see chapters 2 and 3 ).

The impression gained from a study of the introduction of the piano into France is that square pianos became very popular as domestic instruments, presumably on account of their size and low cost, while grand pianos took much longer to be preferred over harpsichords. Perhaps this is not surprising in view of the magnificence of many mid-eighteenth-century French harpsichords which still survive. Certainly the French were strongly attached to the harpsichord as we have seen from Daquin’s remarks, as well as comments such as those by Voltaire, who considered the piano to be a tinker’s instrument compared with the harpsichord. 61 It is unsurprising therefore that the piano only gradually came to be preferred in public performance. Despite the fact that a piano was first heard in public in Paris as early as 1768, the harpsichord still featured on more occasions than the piano a decade later at the Concert Spirituel. From 1780 onwards, however, the piano was used as the main keyboard instrument.

2

DAVID ROWLAND

Pianos and pianists c. 1770– c. 1825

In 1830 Friedrich Kalkbrenner (1785–1849) wrote:

The instruments of Vienna and London have produced two different schools. The pianists of Vienna are especially distinguished for the precision, clearness and rapidity of their execution; the instruments fabricated in that city are extremely easy to play, and, in order to avoid confusion of sound, they are made with mufflers [dampers] up to the last high note; from this results a great dryness in sostenuto passages, as one sound does not flow into another. In Germany the use of the pedals is scarcely known. English pianos possess rounder sounds and a somewhat heavier touch; they have caused the professors of that country to adopt a grander style, and that beautiful manner of singing which distinguishes them; to succeed in this, the use of the loud pedal is indispensable, in order to conceal the dryness inherent to the pianoforte. 1

His remarks could easily have been made twenty or thirty years previously, since his description summarises – albeit in a highly generalised fashion – so many of the essentials of piano making and playing for much of the period covered by this chapter.

‘Viennese’and English grand pianos

Most English grand pianos of the late eighteenth century look much like the Backers grand of 1772, illustrated in Fig. 1.5 . The anonymous and undated grand of Fig. 2.1 is typical of instruments made in the last two decades of the eighteenth century in southern Germany and Austria (generally referred to as ‘Viennese’ pianos). These two instruments therefore illustrate the essential differences in appearance of pianos by members of the English and ‘Viennese’ schools.

Figure 2.1 Grand piano, c. 1795, Stein school, South Germany.

The English piano looks heavier, and is square at the tail, whereas the ‘Viennese’ piano is more elegant, in this instance with a double bentside (the S-shaped piece of wood on the long side of the piano to the right of the performer). Eighteenth-century ‘Viennese’ pianos have knee levers rather than the pedals found on English grands. Internally, the two types of instrument have important differences too. The ‘Viennese’ piano has a substantial base board (the underside of the piano) upon which the internal bracing system is built. The strength of an English piano case is derived largely from a system of internal bracing which holds the sides of the instrument (which are thicker than the ‘Viennese’) together. The action of the two types of instrument differs fundamentally (Figs. 2.2a –2.3b ). ‘Viennese’ hammers are very light and are usually mounted on the key mechanism itself, pointing towards the performer. English hammers are mounted on a separate frame and point away from the performer. Both actions, however, have escapement mechanisms and in both types of piano the hammers are covered with leather (in the case of Fig. 2.3a , multiple layers of leather). The damping systems are placed above the strings in both types of piano, but the ‘Viennese’ system is more effective, as Kalkbrenner later pointed out, and continues up to the highest note, whereas most English pianos have an undamped upper register.

Figure 2.2a ‘Viennese’ grand piano action by Rosenberger, Vienna, c. 1800.

Figure 2.3a English grand piano action by Broadwood, London, 1798.

Figure 2.3b Diagram of the action in Figure 2.3a. A. Check; B. Hammer; C. Hammer rest rail; D. Escapement lever; E. Escapement spring; F. Hammer pivot rail; G. Escapement adjustment.

It is impossible to be certain when and where pianos with ‘Viennese’ actions were first made: relatively few eighteenth-century instruments of this kind still exist, and they are usually undated. Johann Andreas Stein, also a maker of organs, clavichords and a variety of combination instruments (such as harpsichord/pianos), was initially the best-known maker of ‘Viennese’ pianos. He produced them from at least the 1780s and possibly earlier. Several of his pupils set up their own businesses in southern Germany in the last decade or so of the century, and he must have had a sizeable workshop judging by the number of references to his workmanship in late-eighteenth-century journals. Stein died in 1792 but his business was continued by his daughter, Nannette (1769–1833), and son, Matthäus (1776–1842), who both moved to Vienna in 1794. Nannette was married to Johann Andreas Streicher (1761–1833).

Figure 2.2b Diagram of the action in Figure 2.2a. A. Escapement spring; B. Escapement lever; C. Kapsel ; D. Hammer; E. Check rail.

In Vienna, Nannette Streicher (who continued to include her father’s name on her instruments for at least another thirty years) was in competition with many other piano makers. Among them was Anton Walter (1752–1826), who began to make pianos in Vienna probably around 1780. Walter’s action was similar to that of Fig. 2.2a , with a hammer check rail whose function is to catch the hammer as it returns to its resting position (the English action of Fig. 2.3a has individual checks for each hammer). The Stein–Streicher version of the ‘Viennese’ action differed in certain respects from Walter’s; for example, it had no check rail. Walter’s pianos were renowned for their robustness, characterised by a strong tone, especially in the bass, and a heavier touch than some other ‘Viennese’ makers. His instruments were comparatively expensive, but seem to have been preferred by at least some of the leading pianists in the city at the end of the century. 2 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91) acquired one of Walter’s pianos in the early 1780s: the instrument, which still exists, has no maker’s inscription, but there is little doubt that it is by Walter, given its similarities to other known Walter pianos. 3 When Carl Czerny (1791–1857) first visited Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) in 1801 he found a Walter piano in the composer’s room, and Beethoven is known to have been in negotiation with Walter for a piano on another occasion. 4

In England, following Backers’s introduction of the grand piano in London around 1770, other makers such as Joseph Merlin (1735–1803) and Robert Stodart (fl .1775–96) – both, incidentally, makers of combination piano/harpsichords – set up in business. The most important figure, however, was John Broadwood. At first, Broadwood made harpsichords with his mentor Burkat Shudi (1702–73). He then started to make square pianos, probably in 1770, no doubt eager to capitalise on the market already exploited so successfully by Zumpe. He began to make grands somewhat later, and by the early 1780s Broadwood’s workshop was producing harpsichords, grand and square pianos, with an increasing emphasis on the piano side of the business. Wainwright identifies 1783 as the year ‘that the pianoforte began to overhaul the harpsichord in popularity’, though the latter continued to be made in large numbers for several years afterwards. 5 Along with the growth in popularity of the piano came a boom in business – by the end of the century the firm was making in excess of one hundred grands a year, as well as square pianos and harpsichords. Much of this growth is accounted for by increased sales within the United Kingdom, but markets much farther a field were opening up, in such places as India, Russia, the United States and the West Indies.

Mozart, Clementi and the London School

Kalkbrenner (see the quotation above) recognised a London and a Viennese school of playing in 1830 (see p. 22), but he was by no means the first to categorise pianists according to the cities in which they performed. As early as 1802, an article appeared in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung which identified a group of pianists whose names were closely associated with London: Muzio Clementi, Johann Baptist Cramer (1771–1858) and Jan Ladislav Dussek (1760–1812). 6 Ironically, none of them was British, but each had settled in London for some years towards the end of the eighteenth century, during which time they worked together as pianists, composers, teachers and businessmen. No such close-knit school can be said to have existed in eighteenth-century Vienna, though there were several important individuals such as Leopold Koželuch (1747–1818), who arrived in Vienna in 1778. However, by far the most important keyboard player in the region at the time was Mozart.

Mozart’s early experience of keyboard instruments must have been extremely varied. 7 As a very young child, travelling around Austria and southern Germany in the early 1760s, it is unlikely that he would have played any pianos: harpsichords and clavichords still appear to have been the only normally available keyboard instruments in those regions at the time. While it is just possible (but by no means proven) that he encountered some of the first pianos in Paris, London, Holland and Belgium in 1763 and 1764, he played the harpsichord for most, if not all, of the time in Italy in the early 1770s. Back home in Salzburg, there is no evidence that there were pianos except for a square dated 1775 which was owned by Archbishop Colloredo. In fact, the earliest conclusive account of Mozart playing a piano dates from the winter of 1774–5, when he performed on an ‘excellent Fortepiano’ in the home of one Mr Albert in Munich. 8 After this, he played the harpsichord, clavichord and piano, depending on what was available, although once he had settled in Vienna and acquired his Walter piano there can be little doubt that this was the instrument for which he composed.

Mozart’s keyboard music was evidently written for a variety of instruments. The sonatas may all have been composed for the piano, but some of the variations (for example, the C major variations K179) were possibly written for harpsichord. Several of the early concertos were almost certainly for harpsichord (K175, K238, K242, K246), some others are debatable, while those written in Vienna are certainly for piano. Of these, at least two (K466 and K467 of 1785) appear to have been composed with the pedal piano in mind. 9 The evidence – a letter from Mozart’s father, a concert announcement and accounts of those who visited Mozart – shows clearly that Mozart used a pedalboard with independent action and strings which was situated underneath his Walter piano (Fig. 2.4 ). The pedalboard has long since been lost and the only evidence in the music itself for its use is the presence of some bass notes in the first movement of the D minor Concerto K466. It is impossible to play these notes and the chords above them with the left hand alone (Ex. 2.1 ). Exactly what else Mozart played with his feet in this concerto or in other works, and indeed which works he played on the pedalboard, remain largely matters of conjecture; but the reinforcement of the bass register which results from a use of the pedals makes a significant difference to the way in which Mozart’s music is perceived.

Ex. 2.1 Mozart, Piano Concerto in D minor, K466, first movement, bars 88–91 (piano part).

Mozart was particularly admired for his expressive playing, which was praised by no less a pianist than Clementi, following a competition staged between them in 1781. One of the most noteworthy aspects of Mozart’s expressive performance was his use of rubato ; not the constant changing of tempo which is adopted by many pianists today, but a technique whereby the two hands do not quite synchronise. Mozart himself explained it in a letter to his father of 1777 in which he pours scorn on Nannette Stein’s playing:

Figure 2.4 Reconstruction by Richard Maunder of Mozart’s Walter piano with pedalboard.

she will never acquire the most essential, the most difficult and the chief requisite in music, which is, time, because from her earliest years she has done her utmost not to play in time … Everyone is amazed that I can always keep strict time. What these people cannot grasp is that in tempo rubato in an Adagio, the left hand should go on playing in strict time. With them the left hand always follows suit. 10

The way in which some of Mozart’s published music is written suggests that he sometimes notated a rubato (Ex. 2.2 ), although even this amount of rhythmic detail must surely have been inadequate to express the subtlety of Mozart’s playing.

Ex. 2.2 Mozart, Rondo in A minor, K511, bars 85–7.

This kind of rubato featured in the playing of a number of later pianists, notably Fryderyk Chopin (1810–49) (see chapter 4 ) and can be heard in many twentieth-century recordings (see chapter 5 ).

The same letter contains remarks by Mozart on other elements of technique. Commenting on Nannette’s performance he says:

instead of sitting in the middle of the clavier, she sits right up opposite the treble, as it gives her more chance of flopping about and making grimaces. She rolls her eyes and smirks. When a passage is repeated, she plays it more slowly the second time. If it has to be played a third time, then she plays it even more slowly. When a passage is being played, the arm must be raised as high as possible, and according as the notes in the passage are stressed, the arm, not the fingers, must do this, and that too with great emphasis in a heavy and clumsy manner. But the best joke of all is that when she comes to a passage which ought to flow like oil and which necessitates a change of finger, she does not bother her head about it, but when the moment arrives, she just leaves out the notes, raises her hand and starts off again quite comfortably. 11

We should be careful about the conclusions we draw from such a passage. Nannette was only eight at the time, yet she grew to be very well respected as a performer, as was her teacher (whom Mozart also criticises). Perhaps Nannette’s performance was bad; but it is also possible that she had been trained in a school of playing that Mozart disliked and found easy to caricature. However, what is certain from this letter is that Mozart’s ideal technique was based on finger movement only, with an evenness in certain passage-work, which should ‘flow like oil’.

When Clementi recalled his meeting with Mozart in 1781 he confessed himself to have been amazed at Mozart’s lyrical playing. 12 Mozart was less generous: he regarded Clementi as a ‘mere mechanicus ’. 13 Other contemporary writers, however, were dazzled by Clementi’s virtuosity and his playing of fast movements generally – a prominent feature of the ‘London’ school’s style: ‘Clementi’s greatest strength is in characteristic and pathetic Allegros, less in Adagios.’ The same author goes on to describe Dussek’s and Cramer’s style: ‘Dussek played truly excellent, brilliant Allegro movements with great speed, but played the Adagio very tenderly, agreeably and ingratiatingly; Cramer commanded such speed less well, but had an extremely neat and magical style’, which the author found difficult to describe, but which was very ‘singular’ nonetheless. 14

Among the elements of Dussek’s and Cramer’s techniques which later authors singled out for particular mention was their use of the pedals. However, although these pianists undoubtedly contributed much to early pedalling techniques, it was Daniel Steibelt (1765–1823) who had first indicated the use of the pedals in two printed works which were published in Paris in 1793. 15 The nature of most of these markings suggests that pianists were at that time using the pedals for little more than to create a particular tone quality or effect lasting for several bars at a time (Ex. 2.3 ).

Ex. 2.3 Steibelt, Mélange Op. 10, p. 6. O denotes the use of the pedal which, according to the preface to the work, ‘imitates the harp’ and O denotes the use of the sustaining pedal. The symbol signifies the release of the pedal.

Indeed, this was all that could be achieved on the numerous early pianos which had handstops rather than knee levers or pedals to operate the sustaining and other devices. Some of the earliest pedal markings in the works of other composers suggest a similar approach to Steibelt’s, such as the indication to raise the dampers throughout the first movement of Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight’ Sonata Op. 27 No. 2. As Beethoven’s pupil Czerny remarked about a passage in the slow movement of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto which the composer played with constantly raised dampers, this kind of performance worked on eighteenth-century pianos with their relatively small resonance, but it was not viable on later instruments. 16

Pedalling began to be indicated in printed music by members of the ‘London’ school shortly after Steibelt’s arrival there in the winter of 1796–7. The markings of Dussek and Cramer (but not those of Clementi), as well as those in Steibelt’s London works, show how sophisticated their technique had by then become. It is common in these works to see the sustaining pedal depressed for half a bar, or a single beat, for the purposes of creating a certain richness in part of a phrase, or for enabling the pianist to play in a more legato style (Ex. 2.4 ).

Ex. 2.4 Steibelt, Concerto Op. 33, p. 12 (indications for the use of the sustaining pedal).

The pedalling technique in these works is still a long way removed from the kind of constant pedalling that became fashionable in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, but it represents a significant development from earlier eighteenth-century techniques and marks the end of performances ‘on harpsichord or pianoforte’ that were advertised on so many keyboard works of the late eighteenth century. By the end of the 1790s the piano is undoubtedly the only option for the music of the London School. The new pedalling techniques of the late 1790s also gave rise to significant new figurations in compositions of the period (see chapter 8 ).

Grand pianos c. 1790–1825

The period from about 1790 to 1825 was one of intense activity for piano makers, during which the initiative moved between three major pianomaking centres, London, Vienna and Paris.

Most pianos made in London before the 1790s had a five-octave range, from FF to f 3 , although there were exceptions such as Burney’s six-octave Merlin piano of 1777. It appears to have been Dussek who prompted Broadwood to add a further half octave to the standard five-octave range, to take the treble up to c 4 . A letter of Broadwood of 1793 states that ‘We now make most of the Grand Pianofortes in compass to CC in alt. We have made some so for these three years past, the first to please Dussek, which being much liked Cramer Jr. had one off us so that now they are become quite common.’ 17 The piano in question may have been that which Broadwood sold to Dussek on 20 November 1789. 18 By 1792, Broadwood was making six-octave pianos. 19 This was achieved by adding the half octave in the bass (down to CC) that was found on some earlier English harpsichords.

English pianos were vigorously marketed on the continent. French, German and Austrian newspapers contain advertisements for English pianos in the 1780s and 1790s. Members of the London School played their part too, in their continental tours of the late 1790s and early 1800s. Dussek, for example, was contracted to Clementi, who in 1798 had become a partner with James Longman in a firm of piano makers and music publishers following the demise of Longman … Broderip. Dussek sold a number of Clementi’s pianos on the continent. 20 Clementi himself toured Germany, Russia, Italy and Austria in the years 1802–10, selling pianos as he went. 21 He set up a large piano warehouse in St Petersburg with his pupils John Field (1782–1837), Ludwig Berger (1777–1839) and Alexander Klengel (1783–1852), and formed business partnerships with firms such as Breitkopf und Härtel and Artaria. All of this activity placed considerable pressure on some continental makers to keep up with the latest developments in London, while other continental makers were already making changes of their own.

The different compasses of German and Austrian pianos at the end of the eighteenth century are difficult to summarise. Some makers preserved the five-octave range FF–f 3 into the nineteenth century while others exceeded that range at a considerably earlier date. In 1789 and 1790, for example, the Speier Musikalische Real-Zeitung advertised the work of two of Stein’s pupils, Johann Georg Kuppler in Nürnberg and J. C. Bulla in Erlang. Both makers were selling pianos with ranges from FF to a 3 – just over five octaves. 22 Other continental makers at the time commonly used the range FF–g 3 . Joseph Heilmann of Erfurt (son of the better-known Matthäus Heilmann of Mainz) advertised six-octave pianos from FF to f 4 in 1799 while at the same time continuing to make five-octave pianos 23 – it was common for makers to produce more than one model at a time. In Vienna the compass used by makers seems to have stayed around five octaves until just after 1800. Streicher, however, appears to have extended the range from five and a half to six octaves very quickly – probably by 1803 – perhaps as a direct response to English competition.

The six-octave compass of continental and English pianos differed. For some years Broadwood used the six-octave compass down to CC, whereas continental instruments (including French pianos) had six octaves beginning an interval of a fourth higher, at FF. The situation was even more complicated, however, because some English and Irish makers (notably William Southwell (1756–1842), in the closing years of the eighteenth century, and Clementi, from c. 1810) used the ‘continental’ six-octave compass. This confused state of affairs posed obvious problems for composers who wished to write music for the international market, and it is noteworthy that almost all works from around the turn of the century stay within the five and a half octaves, range FF–c 4 , which was manageable on both English and continental extended-compass instruments. There were some exceptions, however, notable among which is the early use of a ‘continental’ six-octave compass in one of Steibelt’s Op. 16 sonatas published in Paris around 1795. An easy resolution of the incompatible six-octave compasses was to combine them in a six and a half octave compass, from CC to f 4 . This happened before 1810 on the continent, and shortly afterwards in London.

Other differences characterised English and continental pianos in the early nineteenth century. In Paris from around 1800 – where Sebastian Erard had begun to make pianos based on the English model – and in Vienna from a few years later, it became customary for pianos to have four pedals (knee levers being generally abandoned at about this time). In addition to the sustaining and una corda pedals, which were the only two normally found on London pianos, continental instruments also used the ‘moderator’ – a strip of material interposed between the hammers and strings which produces a muffled sound (Fig. 2.6 ). On ‘Viennese’ pianos a bassoon effect was also made possible by means of a strip of parchment or silk which was placed against the bass strings to produce a buzzing sound (Fig. 2.7 ). (The moderator was the usual device for muting the sound on ‘Viennese’ pianos in the eighteenth century: the una corda was introduced on these instruments only in the nineteenth century.) The French also used the bassoon, but on some of their instruments there was instead a lute pedal which brought a strip of material into permanent contact with the strings, thereby reducing their vibration, to make a dry, plucking effect. On some extravagant continental instruments there were also drums, bells, triangles and cymbals operated by pedals, or a combination of several pedals and a few knee levers; but there is strong evidence to suggest that professional pianists treated these ‘extras’ with disdain. 24 However, by about 1830 in France, and about 1840 in Vienna, the number of pedals was reduced to the same two found on English pianos – sustaining and una corda .

Figure 2.5 Grand piano by Graf, Vienna, c. 1820.

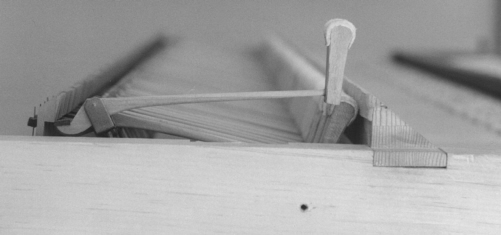

Figure 2.6 Moderator device on a ‘Viennese’ grand piano c. 1800 – tongues of material are interposed between the hammers and strings. To the right of the hammer can also be seen a metal spacer which helps to keep open the space between the soundboard and the wrestplank. The damper rail can be seen at the top of the picture, above the strings.

Figure 2.7 Bassoon device on a grand piano by Streicher, Vienna, 1823.

Other developments in the construction of grand pianos in the early decades of the nineteenth century, and a description of domestic pianos, are discussed in chapter 3 .

Pianists in Vienna and Paris

A number of pianists came to prominence in Vienna following Mozart’s death. Beethoven was the most famous: having settled in the city in 1792 he quickly established himself as a leading performer until deafness forced him progressively to retire from public performance during the early years of the nineteenth century. In the years 1795–9 Beethoven had a serious rival in Joseph Wölfl (1773–1812), but like many pianists of his generation, Wölfl did not stay in any one city for very long, and departed for Prague, Dresden, Leipzig, Berlin and Hamburg on his way, eventually, to Paris and London. The other pianist of note at the time was Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778–1837), one of Mozart’s pupils, whose style of playing differed markedly from Beethoven’s (see below).