f it came to scouring Britain to find the city that could claim the title, ‘City of Scaffolds’ then York would be a main contender. Since early medieval times, the place had gallows in all kinds of places, either in the city or in suburbs and neighbouring villages. Not only did the castle and town gaol have gallows, but also the higher clergymen: they organised their own courts and punishments of course. In addition, there were the lords of the manors in the environs of York. Up to the 1890s, even after Armley gaol in Leeds had taken over county responsibilities for hang-ings, there were still executions at York, in the town gaol, rather than at Knavesmire.

f it came to scouring Britain to find the city that could claim the title, ‘City of Scaffolds’ then York would be a main contender. Since early medieval times, the place had gallows in all kinds of places, either in the city or in suburbs and neighbouring villages. Not only did the castle and town gaol have gallows, but also the higher clergymen: they organised their own courts and punishments of course. In addition, there were the lords of the manors in the environs of York. Up to the 1890s, even after Armley gaol in Leeds had taken over county responsibilities for hang-ings, there were still executions at York, in the town gaol, rather than at Knavesmire.

Walmgate Bar, York, where felons were brought to hang just a hundred yards beyond. The author

Where the lucky ones went? Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania). The author

Knavesmire, perhaps more famous for its horse-racing, is the York place-name that always sends a shiver down the spine of crime historians. There, not only the likes of Dick Turpin were hanged, but a vast number of other felons, from highwaymen to small-time thieves. Those who did not keep their lives to moulder in the hulks (the prison ships) or to be transported first to America and then to Van Dieman’s Land, found themselves in the condemned cell at York Castle prison.

Visitors to York today may still see the prison walls and cells. That dark history has become part of the modern ‘heritage’ trail and the city has its tourist-centred ‘York Dungeons’ experience to match that of the London Dungeons. But the hard fact is that, first in the city and then later on the Knavesmire, hundreds of people met their deaths either on a plain scaffold or on the ‘three-legged mare’ on the Knavesmire. This was a triangular frame, allowing for three villains to be hanged at the same time, and there are old prints in existence that show these hangings. The hangings often took place on race-days, and by the early nineteenth century, when the executions at the Knavesmire began, the good middle class folk of the city and their well-off racing visitors began to complain that the hangings were distracting the crowds from the racing, and also that it was unseemly to have such disgusting deaths going on while others were having fun and quaffing their beer.

Nevertheless, the deaths went on, and the question as to who should oversee the ropes and hoods, the scaffold and noose, was always a tough one. It had never been easy to recruit hangmen. Fortunately, the habit of offering condemned men a commutation of sentence devel-oped, and hangmen were often rogues who did the nasty work to save their necks.

There are two notorious York hangmen in the records: William Curry and Thomas Askern. Curry was also known as William Wilkinson, so matters are somewhat complicated. He was known as ‘Mutton Curry’ as he had two convictions for sheep-stealing. Fate had been on his side because his death sentences had been commuted twice. He was waiting to be sent to Australia on the second occasion when he turned hangman. In fact he was still a convicted felon, and was a prisoner as well as a hangman until 1814. Curry was to become a true local character - a man with a drink problem, and that comes as no surprise when we reflect on the nature of his work.

There had been no professional training of course. A man who turned executioner had no means of practising his trade other than a knowledge of butchery. If a man had been a farm worker, he would know about tying beasts and he would be skilled with a blade. He might also know a little about weights if he had used a pulley for grain in milling work. But he could only really learn by doing, and that is why, in the twentieth century, after a more rigorous training was in place, dummies were used for drop practice. But in Curry’s time it was an occupation with high-level stress and the gin bottle was very useful.

St Margaret’s Church, York, where paupers (some of the hanged) were buried. The author

Frontispiece to York Castle (1829) one of the early true crime books.

There is some confusion about Curry’s real identity. His date of birth was around 1761 but that is not certain. He was from Romanby and his local thefts had led him into deep trouble., first in 1793 when he stole some sheep from an innkeeper at Northallerton., William Smith. Sheep-stealing was a capital offence., and the magistracy took a very serious and often inflexible attitude to that offence. But lady luck smiled on Curry: he was fortunate that his commutation for transportation did not happen; he was sent to the Woolwich hulks. That was obviously far from pleasant, but at least he was not on his way to a penal colony across the other side of the globe. Nevertheless., Curry in his time on the prison ships would have had a very hard time; in the first thirty years in which these hulks were used., one in four convicts died. He would have spent much of his time lifting timber on the Thames shore and when he was not working he may well have suffered the fate of one young prisoner who told an enquiry that he had been in irons while working and sleeping and that he had worn the same clothes for two years. He had also been flogged, and one of the worst cases of abuse there was the case of an old man who had been flogged with a cat’o’nine tails thirty-six times for being five minutes late for a roll call.

But Curry emerged from that, and somehow returned and then at York he took the chance of being the city hangman. What he was called has been a puzzle for historians; one writer gives his name as John; but he was reported as William in 1821 when there was a fairly substantial report on his work. A new drop behind the Castle walls was made in 1802 and it seems that Curry did well, and in 1813 he was the man who hanged the Luddites, so he would come to be recognised. This was a high-profile affair: the machine-wreckers had attacked Rawfolds Mill near Bradford, and it had taken the military and indeed an informer to finally track them down. A new offence of taking at illegal oath was put on the statute book as a capital crime. No less than fourteen felons were hanged at the first session and more were to follow.

The death cell at York. The author

Curry has to go down in the records as one of the most capable, because he handled this well and he did the work in two shifts, seven men at a time. The York Courant noted that, ‘The spectators were not so numerous on the second occasion, owing to the time of the execution being altered from two o’clock to half past one. The entrance to the Castle and the place of execution were guarded by bodies of horse and foot soldiers.’ The Luddites had conducted a reign of terror across the area spanning Huddersfield and Halifax, and even towards the Lancashire border. They had been fighting the introduction of mechanised shearing, displacing one of the most skilled trades in clothing manufacture.

Unfortunately, whatever his prowess and expertise before 1821, he will be remembered as the hangman who made a terrible hash of executing robber William Brown on that date. Curry had two execution appointments that day, and he had hanged the first victim at the Castle, and Brown was waiting for him at the City Gaol after that. Curry was very tired by the time he reached the second place of execution, and he also ‘took a drop’ to steady himself. The local Gazette has this explanation: ‘ . . . in proceeding from the County execution . . . to the place of execution for the City, he was recognised by the populace, who were posting with unsatiated appetites from one feast of death to another . . . they hustled and insulted the executioner to such a degree during the whole of his walk that he arrived nearly exhausted . . .’

Curry then had a few drinks to steel himself to the job; he decided to taunt and entertain the crowd by flapping the ropes around and saying, Some of you come up and I’ll try it!’ After that, he botched the hanging of Brown quite scandalously, as one report said, ‘The executioner, in a bungling manner and with great difficulty placed the cap over the culprit’s eyes and attempted several times to place the rope around his neck, but was unable . . .’ He had prepared the rope too short. It was all becoming more than embarrassing - it was disgusting, though no doubt some of the callous and drunken crowd enjoyed it.

We tend to think of extreme barbarity and extreme sensual pleasure when we consider the media images of the Regency period. But there was plenty of humanitarian concern and conscience as well. In the same year that Curry was bungling at York, The Manchester Guardian reported on another hanging with the head, ‘Dreadful execution of our fellow creatures’:

Before daylight on Tuesday morning a considerable concourse of people were assembled to witness the execution of three of our fellow creatures: Ann Norris, for a robbery at a dwelling house; Samuel Hayward, for a burglary at Somerstown, and Joseph South, a youth apparently about 17. There appeared in him a perfect resignation to his fate, which will be best appreciated by his own words: “I am going to die, but I am not sorry for it – I am going out of a troublesome world.” The woman was (as usual) last; she seemed deeply affected. At 14 minutes past eight the drop fell, and they closed their earthly career. When will some mode of punishment be found to save these sacrifices of life?

Mary Bateman, hanged at York. From York Castle (see bibliography).

But the world of 1820 was one sustained by savage repression in all areas. In the Army, in 1822, a private was tried by court martial for stealing a silver spoon from a mess. He was given 300 lashes. Curry was operating in a context of duels, bare-knuckle fist fights, dog-fighting and frequent muggings and robberies on the road and in homes after dark. The mob at York expected something bloodthirsty to treat their vicarious pleasure. With the bungled death of Brown they certainly had that. When at last the felon was dead, people in the crowd shouted, ‘Hang him . . . hang Jack Ketch! He’s drunk!’

Curry’s drinking was clearly an ongoing problem. Later that year, at York Castle, he had the task of hanging five men. But here we have arguably the most farcical event in Curry’s career. He did in fact hang the men successfully, but then fell down with them into the drop area. As the local paper reported: ‘By an unaccountable neglect of the executioner, in not keeping sufficiently clear of the drop, when the bolt was pulled out, he fell along with the malefactors, and received some severe bruises.’ Of course, the crowd were highly amused by that; apparently, ‘a shout of joy rose from the crowd’ when Curry staggered to his feet and clambered back to the platform. This was all highly embarrassing of course., for the good people of York. But the fact at that time was that hangmen were difficult to find. The authorities persevered with him. The sheriff could easily have dismissed him from the scene then., and of course., he would have been within his rights to sack the man.

Curry retired in 1835 and he was then to be a guest of the Thirsk Parish Workhouse where he died in 1841., aged seventy-six., although there is some doubt about his date of birth. In his career., he had hanged dozens of people., had two convictions for sheep-stealing., and was surely remembered in York history as the drunk who had his tipple of gin to steel himself for his professional duties.

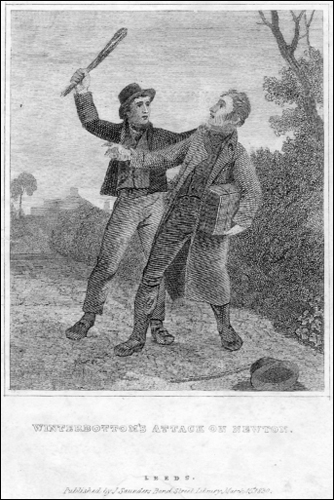

Winterbottom (hanged by Curry) depicted in York Castle (see bibliography)

Thomas Askern., another controversial figure., appeared on the scene in 1856., another former prisoner., but in gaol for debt rather than for any violent offence. There must have been the usual deal done for his release a little time after his appointment, because he was living in Rotherham in 1859. Once again, we have a man whose work was marred by bungling incompetence. He was a man with a varied former career - farmer, butcher, flower-seller, and parish overseer from Maltby. In his time in the debtors’ prison he was described as ‘a man without money and without friends’.

His first victim was the celebrated William Dove, who had poisoned his wife in Leeds, after a shady involvement with a ‘wise man’ and quack doctor called Harrison. But, as research by Owen Davies has made clear, there are some doubts about this. Askern denied that he hanged Dove and a minor controversy ensued. Dove was hanged at York on 9 August 1856, after one the most prominent murder cases of the century, and he died in front of a huge crowd of almost 20,000 people. He wrote to Yorkshire newspapers threatening a libel action if they did not withdraw their statements that he had hanged Dove. There was even a letter published in Manchester supposedly from a schoolmaster in York, saying that Askern was not the executioner of Dove. But when traced, the man denied writing it. It seems that Askern’s earlier life and hidden debt were indicative of a personality capable of self-deception as well as attempts at deception of others. But some inmates of the debtors’ prison wrote to the Leeds Mercury to confirm that the man in question was indeed Askern. The hangman had actually attacked one man in the gaol with a stick for saying that he (Askern) had hanged Dove. We have to reflect that perhaps Askern did not want to be linked to a case in which a man died after being the creature of a Svengali-like magician (Harrison) and that there had been posthumous sympathy for Dove, the young farmer and Methodist from a ‘good family’ in Yorkshire.

In many of his hangings, there were errors and incompetence. It has to be noted that the old habit of giving the hangman cash to arrange a swift death was apparently not still extant at this time, or at least it is not often referred to. There would still be profit from the surgeons of course. But Askern, along with many others at the time, carried on making a mess of things. In a double hanging at Armley a black cloth was put around the victims but still, despite the fact that bodies were out of sight of the crowd, a reporter said that one of the men died quickly but that the other was slowly strangled over several minutes. In 1865, when he was hanging Matthew Atkinson, the rope snapped and the man fell fifteen feet; he was unhurt and stood there for twenty minutes until Askern had a second attempt.

Surely the most shameful bungling of Askern’s career was the case of thirty-seven-year-old John Johnson from Bradford. On Boxing Day 1876, fortunately after hangings in public ceased (1868); Johnson was enjoying a drink with Amelia Walker at the Bedford Arms in Wakefield Road; everything was relaxed at first, but Amelia had other men-friends and one of these, Amos White, came into the bar. White made advances to her and she called for Johnson who was at the bar; there was a fight and White was coming off best, but then Johnson ran out, only to return shortly afterwards with a gun. He fired the shotgun at White’s chest and then bystanders wrestled Johnston to the ground. Johnson was arrested and charged with murder, and after trial at York Assizes, he was sentenced to die. Waiting for him was Askern. After 1867, legislation was in place concerning capital crimes, and the huge number of such offences before that date was reduced to just murder, treason; the only complications arose when issues of insanity defences arose, or of course, when manslaughter was a possibility. But for Johnson, a crowd of drinkers at the pub had seen him leave and then return with the gun. This was a very clear case of murder and he had to hang for it.

When Johnson was made ready for his last seconds of life, standing on the trap on 3 April 1877, the lever was pulled but the trap broke and Johnson fell through the hole, his feet not kicking air but still firmly on wood. He had to be sat down, groaning on a chair, attended by the gaol warders, who were always ready to help a poor criminal if the death was being handled too slowly and clumsily. Johnson had to be taken to the trapdoor and prepared again. The usual cluster of officials were with him - governor, doctor, priest and sheriff - and the mental preparation for death was experienced a second time, with unbelievably horrific fear running through the man’s body. His heart must have been almost bursting through his chest, and whatever resolve he had previously gathered was surely gone as he tried to prepare himself a second time.

It was a total outrage: the drop was only partially successful and his death was slow and horrific to behold. He struggled for several minutes in his death throes. According to one anonymous journalist, writing in the late 1870s, Askern became a man ‘shunned and despised and often liable to insults and desperate encounters in public company.’ Askern had a final year in office but hanged no one: for the one execution that did take place that year, William Marwood was brought in from Lincolnshire. Askern died in Maltby, at the age of sixty-two, in 1878. After his death, the hangman of England would be national, rather than provincial, with general responsibilities and more media presence. The new hangmen would operate in Ireland as well as in England.

After 1868 executions not being public, the barbaric days at York described by historian G Benson were a thing of the past. Benson wrote: ‘York hangings drew crowds from far and near. At such times all the roads to York were thronged. After the railway was opened many came by train and on one occasion in 1856 . . . it was lamented that no cheap excursions were run.’ That was Dove’s hanging, when thousands from Leeds made the short trip north.

As a coda to the tales of horrendous bunglings on the scaffold, the story of John Thurtell is interesting; Thurtell was due to die in 1824 for the murder of William Weare; he is said to have designed his own gallows, partly through fear of the amateurs in charge. His idea was not adopted but he is on record as having said to the prison governor, ‘ I understand that when you rounded people here you put them in a tumbrel and sent them out of the world with a Gee Up but this is rather an ungentlemanly way of finishing a man . . .’

Thurtell made quite an impact at the time. He was hanged at Hertford on 9 January 1824 and he was written about by Sir Walter Scott; he also has a mention in George Borrow’s book Zincali, and the artist Sir Thomas Lawrence wanted to make a cast of the villain’s head. The novelist Bulwer-Lytton used the Thurtell murder case in his novel Pelham. All this shows that by the years of capital punishment reform, in Robert Peel’s first ministry, murder survived as the one sensational crime, forever prominent in journalism, literature and poetry. But for Askern, he was doomed to be placed in the annals of hanging as the arch-bungler. No one wanted to include him in their literary works.